Key Points

RASIP1 is required for stabilizing nascent patent blood vessels in both mice and zebrafish.

RASIP1 is a dynamic effector of EPAC1-RAP1 signaling that controls actin bundling and restricts junction remodeling in vitro and in vivo.

Abstract

Establishment and stabilization of endothelial tubes with patent lumens is vital during vertebrate development. Ras-interacting protein 1 (RASIP1) has been described as an essential regulator of de novo lumenogenesis through modulation of endothelial cell (EC) adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM). Here, we show that in mouse and zebrafish embryos, Rasip1-deficient vessels transition from an angioblast cord to a hollow tube, permit circulation of primitive erythrocytes, but ultimately collapse, leading to hemorrhage and embryonic lethality. Knockdown of RASIP1 does not alter EC-ECM adhesion, but causes cell-cell detachment and increases permeability of EC monolayers in vitro. We also found that endogenous RASIP1 in ECs binds Ras-related protein 1 (RAP1), but not Ras homolog gene family member A or cell division control protein 42 homolog. Using an exchange protein directly activated by cyclic adenosine monophosphate 1 (EPAC1)-RAP1–dependent model of nascent junction formation, we demonstrate that a fraction of the RASIP1 protein pool localizes to cell-cell contacts. Loss of RASIP1 phenocopies loss of RAP1 or EPAC1 in ECs by altering junctional actin organization, localization of the actin-bundling protein nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIB, and junction remodeling. Our data show that RASIP1 regulates the integrity of newly formed blood vessels as an effector of EPAC1-RAP1 signaling.

Introduction

A central question in vascular development is how blood vessels form and maintain patent lumens. During vertebrate embryonic vasculogenesis, endothelial cells (ECs) aggregate into cords followed by de novo lumenogenesis, leading to the formation of lumenized vessels such as the paired dorsal aortae (DA) and yolk sac vascular plexus, which serve as the basis for further vascular expansion and angiogenesis.1,2 The current understanding of cellular mechanisms of de novo endothelial lumen formation is influenced by principles underlying formation of epithelial tubes or cysts.3,4 Vascular lumenogenesis requires membrane rearrangements and trafficking, apical-basal partitioning of repulsive and adhesive proteins, rearrangement of junctional components, and cytoskeletal remodeling.2,5-7

Stabilizing vessels is critical to continued growth and development of an embryo. In murine development, onset of circulation8 coincides with active growth of the DA and yolk sac vascular plexus.2,9 Subsequent angiogenesis and remodeling involve extensive cell movement and rearrangement.10-12 Nascent vessels must be stable to permit circulation and withstand increasing shear stress, while allowing dynamic growth and remodeling. Vascular permeability is tightly regulated throughout development and adult life as changes in vessel permeability contribute to pathologies including hemorrhage and edema.13,14 EC-EC junctions are essential in control of vascular remodeling and permeability, and the mechanisms involved in their assembly and disassembly are under intense investigation. Key components of EC-EC tight junctions (TJs) and adherens junctions (AJs), such as zona occludens 1 (ZO-1) and vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin), critically influence vascular development and lumen stabilization in vivo,14-16 yet the complete molecular ensemble that regulates EC junctions remains to be defined.

A key regulator of junction formation is the small GTPase Ras-related protein 1 (RAP1).17 Membrane signaling events trigger the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which binds to the RAP1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor 3 (RAPGEF3 or exchange protein directly activated by cAMP 1 [EPAC1]) to activate RAP1, triggering a cascade leading to stabilization and linkage of cortical actin to AJ and TJ complexes.18,19 Modulation of RAP1 activity affects endothelial barrier function.13 Disruption of RAP1 signaling in ECs leads to increased permeability and a failure to form stable endothelial tubes.20,21 Furthermore, activation of RAP1 signaling increases density of and cross-linking of cortical actin with VE-cadherin, and promotes stable cell-cell contacts.22 RAP1 signaling has also been linked to the recruitment of nonmuscle myosin II (nmMHCII) to cell-cell junctions,23 leading to junction stabilization. Despite the importance of this pathway, the EPAC1-RAP1 effectors that mediate junction stabilization in ECs remain to be determined.

Prior work implicated Ras-interacting protein 1 (RASIP1) as a critical regulator of vascular lumen formation.24-26 It was reported that continuous patent lumens were globally absent in all blood vessels24 in Rasip1 knockout mice, and absence of vascular tubes was evident at all stages examined,24 resulting in failure to initiate circulation.24 This was proposed to be a consequence of loss of adhesion of Rasip1-deficient ECs to extracellular matrix (ECM), thus disrupting the transition from vascular cords to lumenized vessels.24 This model proposes that RASIP1-dependent EC-ECM adhesion is essential for de novo lumen formation.

We have independently evaluated the role of Rasip1 in vascular development, using mouse and zebrafish genetic models, as well as many in vitro biochemical and cell biology assays. The data presented here demonstrate that Rasip1 is essential for embryonic vascular development but is not required for global de novo lumen formation through EC-ECM adhesion. Instead, patent lumen is evident in many types of vessels. Furthermore, intralumenal primitive erythrocytes are found throughout Rasip1−/− embryos, indicating that the developing vascular network permits circulation. However, vessels in the Rasip1 mutant embryos leak erythrocytes and ultimately collapse. We report that a pool of RASIP1 localizes to cell-cell junctions in an EPAC1-RAP1–regulated manner, and that RASIP1 is required for actin bundling at junctions in response to RAP1 activation. Loss of RASIP1 leads to defective cell-cell junctions and promotes junctional remodeling as evidenced by increased discontinuous/focal AJs. We propose that RASIP1 serves as a junctional effector of the EPAC1-RAP1 signaling axis to stabilize nascent vessels.

Methods

Animal generation and husbandry

Details regarding construction of Rasip1 knockout mice is in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website). For timed pregnancies, mid-day of vaginal plug detection was defined as E0.5. Zebrafish strains Tg(kdrl:EGFP)s843, Tg(fli1a:EGFP)y7, and Tg(gata1:DsRED)sd2 were acquired from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZIRC). All animal studies were approved by the Genentech Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, or by the University of Auckland Animal Ethics Committee. Mouse colonies were maintained in a barrier facility at Genentech, conforming to California state legal and ethical standards of animal care.

Histology

Embryos were collected and stained as described.27 For whole-mount imaging, embryos were cleared in a glycerol series. Frozen sections were permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes prior to blocking and incubation with antibodies. Specific microscopy details are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Antibodies

Antibodies are described in the supplemental Methods.

Cloning of zebrafish rasip1

Expressed sequence tag (EST) clones were obtained from Open Biosystems. Zebrafish rasip1 complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were cloned by 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) with the SMART RACE cDNA Amplification kit (Clontech) using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase (EMD Biosciences). RACE clone sequences were used to obtain full-length cDNA by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction using total RNA from 30 hours postfertilization (hpf) zebrafish embryos. The full length cDNA sequence for zebrafish rasip1 (JF519850) was deposited in GenBank.

Morpholino injections

RNA interference

Short interfering RNA (siRNA) sequences against mouse Rasip1 and human RASIP1 are described in supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Cell culture

Pooled human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) (Lonza) cultured in complete EGM-2. MS1 (ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). siRNA transfections were performed with DharmaFECT 1 (Dharmacon) or siPORT Amine Transfection Reagent (Ambion) with equivalent results.

Lentivirus preparation and infection

Lentiviral vector encoding RASIP1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (Thermo Scientific/Open Biosystems, RHS1764-9693195; Oligo ID V2hS_173885) or pGIPZ control vector were cotransfected with pCMVΔ8.9 and pVSV-G into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Virus-containing supernatants were filtered (0.45 μm) and titered using HUVECs. HUVECs were infected with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 to 5 per cell and selected with 1 μg/mL puromycin.

In vitro immunofluorescence and quantification

HUVECs were grown on glass chamber slides (LabTek) or on #1.5 glass coverslips (Fisher) coated with 5 μg/mL fibronectin. Sp-5,6-Dichloro-cBiMPs (cBiMPs) (Enzo Life Sciences) and 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in cytoskeleton buffer,29 permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (unless noted in text), and blocked in 10% normal goat serum (BioWorld) in 0.2% Triton/PBS. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer.

Morphometric analysis and quantification

Detailed procedures are described in the supplemental Methods.

GTP loading assays

Confluent HUVECs were treated with EGTA for 10 minutes, and treated with cBiMPS for 10 minutes. RAP1 guanosine triphosphate (GTP) loading was assessed using the Active Rap1 Pull-Down and Detection kit (Pierce).

GST pull-down assays

Purified RAP1A–glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Sigma-Aldrich), Ras homolog gene family member A (RHOA)-GST, and RAC1A-GST (Novus) were incubated in cell lysis buffer with 10 μM guanosine diphosphate (GDP) or GTPγS (Millipore) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Proteins were then added to HUVEC lysates and incubated for 30 minutes on ice. Glutathione-sepharose was added; the mixture was incubated at 4°C for 2 hours. Beads were washed 3 times in lysis buffer and boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) buffer prior to SDS-PAGE and western blotting.

Angiogenic sprouting

Angiogenic sprouting assays were performed as described.30

Scratch wound assay

HUVECs were plated at 20 000 cells/well in a 96-well plate and scratched the next day with a pipette tip, washed, and placed in indicated media. Cells were imaged every 20 minutes for 16 hours in an Essen IncuCyte system. Detached cells were manually quantified using NIH ImageJ.

Results

Rasip1 knockout mice form patent lumens

In a bioinformatics screen for vascular-enriched genes, and in agreement with previously published data,24,25 we identified RASIP1 as highly expressed in human ECs (supplemental Figure 1A) and confirmed vascular expression by in situ hybridization in mouse embryos (supplemental Figure 1B). To investigate the in vivo role of Rasip1, we generated a knockout targeting exon 3 of the mouse Rasip1 locus (supplemental Figure 1C), eliminating the same exon as previously reported,24 predicted to create a truncated protein of ∼40 amino acids. Correct targeting was confirmed through polymerase chain reaction and genomic sequencing (supplemental Figure 1D). Western blots using whole-embryo lysates confirmed loss of RASIP1 protein in homozygous knockout embryos (supplemental Figure 1E). No overt morphological defects were seen earlier than E8.75 (supplemental Figure 1F). At E9.0, Rasip1−/− embryos were slightly smaller in size, pale, and displayed prominent hemorrhage and pericardial edema, indicative of cardiovascular defects (Figure 1A-B). Large pools of erythrocytes were observed at random locations throughout Rasip1−/− embryos (Figure 1B,E-G), suggesting a partially functional circulatory system existed since primitive erythrocytes are generated in the yolk sac at and prior to this developmental stage.31 At E10.5, Rasip1−/− embryos were markedly smaller than control littermates with exacerbated edema and hemorrhage (Figure 1C-D). Viable Rasip1−/− embryos were not detected past E10.5. Taken together, we conclude that targeted disruption of mouse Rasip1 results in abnormal cardiovascular development and midgestational lethality.

Rasip1 knockout mice die in midgestation with vascular defects. Brightfield images of mouse embryos (A-G) with the indicated ages and Rasip1 genotypes, showing pericardial edema and multifocal hemorrhage in Rasip1−/− embryos at E9.5 and E10.5; Rasip1−/− embryos were also significantly smaller than control at E10.5. Immunofluorescence staining of CD31 plus CD105 (red) and DAPI (blue) in whole-mount embryos (H-K) or transverse sections of DA (L-O) with the indicated ages and genotypes revealed irregular DA in Rasip−/− embryos. RBC autofluorescence (green) in panels J-O showed that erythrocytes were present in dilated vessels or in extravascular space in Rasip−/− embryos. Arrows indicate DA. DAPI, 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole; so, somite; ss, somite stage. Panels H-I, ventral view, rostral to the left; panels J-K, lateral view. Scale bars: (A-B,E-G) 0.5 mm; (C-D) 1 mm; (H-I) 50 μm; (J-K) 100 μm; (L-O) 10 μm.

Rasip1 knockout mice die in midgestation with vascular defects. Brightfield images of mouse embryos (A-G) with the indicated ages and Rasip1 genotypes, showing pericardial edema and multifocal hemorrhage in Rasip1−/− embryos at E9.5 and E10.5; Rasip1−/− embryos were also significantly smaller than control at E10.5. Immunofluorescence staining of CD31 plus CD105 (red) and DAPI (blue) in whole-mount embryos (H-K) or transverse sections of DA (L-O) with the indicated ages and genotypes revealed irregular DA in Rasip−/− embryos. RBC autofluorescence (green) in panels J-O showed that erythrocytes were present in dilated vessels or in extravascular space in Rasip−/− embryos. Arrows indicate DA. DAPI, 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole; so, somite; ss, somite stage. Panels H-I, ventral view, rostral to the left; panels J-K, lateral view. Scale bars: (A-B,E-G) 0.5 mm; (C-D) 1 mm; (H-I) 50 μm; (J-K) 100 μm; (L-O) 10 μm.

As the presence of red blood cells (RBCs) in Rasip1−/− animals indicated circulation, we analyzed early blood vessels of Rasip1−/− mice in more detail. Control and Rasip1−/− embryos at the 3 to 6 and 7 to 10 somite stage (ss) stained with a combination of the EC markers CD31/platelet EC adhesion molecule and CD105/endoglin displayed paired DAs assembled in appropriate bilateral positions (Figure 1H-I). However, the width of the mutant DAs was irregular along the rostral-caudal axis (Figure 1I). Similar results were observed with staining of Flk1 (supplemental Figure 2). By E9.0, the DAs were highly distorted as localized collapse, breakage, and dilation appeared at different axial positions in Rasip1−/− embryos (Figure 1J-O); ECs were disorganized or dispersed in some vessels, and RBCs collected within the aberrant vessels or were found in the extravascular space (Figure 1J-O; supplemental Figure 3).

Lumenization of murine DAs begins with formation of a linear space >5 μm (or cross-sectional area of >20 μm2) between ECs, the minimal space able to accommodate a single RBCs.2 Lumen formation is complete by 6 ss, and lumenal area increases as angiogenic sprouting initiates from the DA.2 To determine whether vascular lumen formed in Rasip1−/− embryos, we analyzed serial transverse sections along the entirety of DAs from mutant and heterozygous animals pooled at 1 to 2 ss, 3 to 6 ss, and 7 to 10 ss. At 1 to 2 ss, EC cords were detected in both Rasip1+/− and Rasip1−/− embryos (Figure 2A,E); some cords had slits with a cross-sectional lumenal area at or below 20 μm2. By 3 to 6 ss, most DA sections, including 80% of sections from Rasip1−/− embryos, developed a lumenal space >20 μm2 (Figure 2B,F,K), indicating that significant portions of DAs in all embryos formed lumen large enough to accommodate a single RBCs. From 7 to 10 ss, Rasip1−/− DAs showed increased variation in the lumenal areas along the rostral-caudal axis, with evidence of vascular collapse (including increased extravascular space adjacent to the mesenchyme) in 1 section adjacent to another with seemingly normal lumen (Figure 2G-H). In contrast, control littermates showed consistent lumenal size in adjacent sections (Figure 2C-D). Coexistence of collapsed and patent vessels was observed in contralaterally paired DAs in the same sections from Rasip1−/− embryos (Figure 2J), but not in control embryos (Figure 2I). At 7 to 10 ss, all control embryos and 3 of 5 mutant embryos showed patent lumen in the majority of sections; even in the 2 most severely affected knockouts, ∼50% of the sections examined had patent lumen (Figure 2L). Two possible explanations exist for the phenotypic heterogeneity in mutant embryos: partial penetrance of a failure in de novo lumen formation, or instability of nascent vessels. If partial penetrance of lumen formation defects was the reason, then a subset of mutant embryos that were normal at 7 to 10 ss should develop normal DAs at later stages. However, severe DA morphological defects and hemorrhage were seen in 100% of E9.0 mutant embryos (n = 25, Figure 1B,E-G,K,M-O), arguing against partial penetrance of lumen formation defects. Furthermore, RBCs were present in locations such as the cranial vascular plexus (Figure 1F-G), where hematopoiesis does not occur.

Rasip1−/− mice form vascular lumen with evidence of localized collapse. Transverse sections of DAs from Rasip1+/− (A-D,I) and Rasip1−/− (E-H,J) embryos at the indicated somite stage were stained with CD31+CD105 (red) and DAPI (blue). Note that panels C-D,G-H are from adjacent sections, indicating localized collapse of the aorta in Rasip1−/− embryos. In panel J, note that the left DA collapsed, whereas the right DA was inflated. Scatter plots of DA lumenal areas from serial sections from Rasip1+/− (HET) and Rasip1−/− (KO) embryos at 3 to 6 ss (K) and 7 to 10 ss (L). The 20-μm2 cutoff line (red) indicates functional blood vessel (or DA) area. Rasip1−/− DAs display a wider variation of lumenal areas. Each point represents an individual area measurement of a DA section. Scale bars: (A,E) 20 μm; (B-D,F-H) 10 μm; (I-J) 25 μm.

Rasip1−/− mice form vascular lumen with evidence of localized collapse. Transverse sections of DAs from Rasip1+/− (A-D,I) and Rasip1−/− (E-H,J) embryos at the indicated somite stage were stained with CD31+CD105 (red) and DAPI (blue). Note that panels C-D,G-H are from adjacent sections, indicating localized collapse of the aorta in Rasip1−/− embryos. In panel J, note that the left DA collapsed, whereas the right DA was inflated. Scatter plots of DA lumenal areas from serial sections from Rasip1+/− (HET) and Rasip1−/− (KO) embryos at 3 to 6 ss (K) and 7 to 10 ss (L). The 20-μm2 cutoff line (red) indicates functional blood vessel (or DA) area. Rasip1−/− DAs display a wider variation of lumenal areas. Each point represents an individual area measurement of a DA section. Scale bars: (A,E) 20 μm; (B-D,F-H) 10 μm; (I-J) 25 μm.

We next examined vascular development in the yolk sac. At 7 to 10 ss, the morphology of the yolk sac primitive vascular plexus was indistinguishable between control and Rasip1−/− embryos (supplemental Figure 4C-D). By E9.0, the proportion of yolk sac vessels that were patent and filled with RBCs was identical in both control and Rasip−/− yolk sac vasculature, although the Rasip1−/− yolk sac vasculature failed to remodel (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Our findings argue that the Rasip1−/− vasculature is unstable, yet supports circulation of yolk sac–derived primitive erythrocytes for a period prior to hemorrhage. This is further supported by the appearance of RBCs within multiple types of vessels in mutant embryos at E9.0 (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 3).

Zebrafish rasip1 regulates vascular integrity

Because cardiac function has a greater influence on embryonic vascular development in mice than in zebrafish,32,33 we used zebrafish embryos to further characterize the role of Rasip1 in vascular development. Using the human RASIP1 sequence, we identified an EST clone in the Ensembl database (www.ensembl.org) as a possible RASIP1 ortholog. The EST was sequenced and used to clone full-length cDNA, encoding a protein with high homology (41% identity/54% similarity) to mouse and human RASIP1, which we infer to be the zebrafish ortholog. Zebrafish rasip1 was highly expressed in the developing embryonic vasculature (supplemental Figure 5A).

We investigated the role of rasip1 in zebrafish vascular development via injection of 2 independent antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) against rasip1 in the established Tg(kdrl:EGFP)s843 line, where green fluorescent protein (GFP) marks embryonic vessels.34 At 28 hpf, lumen formation, erythrocyte migration into nascent vessels, and circulation in the DA and posterior cardinal vein (PCV) were comparable between control and KD embryos (Figures 3A-B; supplemental Videos 1-2). Moderate pericardial edema and a delay in intersomitic vessel sprouting were observed in the KD embryos (n = 49 of 64, Figure 3B). We examined vascular lumen formation and circulation using Tg(kdrl:EGFP)s843;Tg(gata1:DsRED)sd2 double transgenic animals, where both vasculature and circulating RBCs can be visualized in live embryos.35 At 28 and 48 hpf, the diameters of the DA and PCV in KD embryos appeared irregular along the anterior-posterior axis (n = 53 of 79, Figure 3C-F). Furthermore, multifocal hemorrhage was apparent as extravascular RBCs were observed in rasip1 KDs (Figure 3D,H; supplemental Figure 5D). Despite this, circulation of RBCs through vessels with patent lumens was evident (Figure 3C-H; supplemental Videos 1-2). Thus, loss of rasip1 does not compromise vascular lumen formation. Instead, vascular tubes are distorted and leaky (supplemental Figure 5D,H), leading to hemorrhage. Our data show that Rasip1 is not required for lumen formation, but stabilizes newly formed vessels.

Knockdown of rasip1 in zebrafish affects vascular integrity. (A-B) Tg(kdrl:EGFP)s843 zebrafish embryos at 26 hpf were injected with control (ctrl) morpholino (MO) (A) or rasip1 MO (B). Arrows indicate dorsal aorta. Arrowheads indicate PCV. Insets show magnification of trunks. Note stalling of intersomitic vessels (ISVs). (C-F) Confocal projections of trunk axial vessels from control (C,E) or rasip1 (D,F) MO-injected Tg(kdrl:EGFP)s843;Tg(gata1:DsRED)sd2 double transgenic live embryos at 48 hpf. Images are maximum projections of 3 confocal slices. Note irregular appearance of the rasip1 KD DA and PCV (green) (D,F), which have patent lumen and contain circulating RBCs (red). (G-H) Maximum projections of head vasculature in ctrl (G) and rasip1 (H) MO-injected double transgenic fish at 48 hpf. Intralumenal RBCs were observed in both embryos (insets), whereas extravascular RBCs were only seen in the rasip1 KD embryo. The streaking appearance of red signal in panels C-F is due to rapid movement of RBCs. Scale bars: (A-B) 100 μm; (C-H) 20 μm.

Knockdown of rasip1 in zebrafish affects vascular integrity. (A-B) Tg(kdrl:EGFP)s843 zebrafish embryos at 26 hpf were injected with control (ctrl) morpholino (MO) (A) or rasip1 MO (B). Arrows indicate dorsal aorta. Arrowheads indicate PCV. Insets show magnification of trunks. Note stalling of intersomitic vessels (ISVs). (C-F) Confocal projections of trunk axial vessels from control (C,E) or rasip1 (D,F) MO-injected Tg(kdrl:EGFP)s843;Tg(gata1:DsRED)sd2 double transgenic live embryos at 48 hpf. Images are maximum projections of 3 confocal slices. Note irregular appearance of the rasip1 KD DA and PCV (green) (D,F), which have patent lumen and contain circulating RBCs (red). (G-H) Maximum projections of head vasculature in ctrl (G) and rasip1 (H) MO-injected double transgenic fish at 48 hpf. Intralumenal RBCs were observed in both embryos (insets), whereas extravascular RBCs were only seen in the rasip1 KD embryo. The streaking appearance of red signal in panels C-F is due to rapid movement of RBCs. Scale bars: (A-B) 100 μm; (C-H) 20 μm.

Loss of RASIP1 in vitro results in unstable lumen and defects in EC-EC attachment

We then investigated the cellular mechanism for vascular instability using validated siRNA and shRNA in vitro. Surprisingly, we found no effect of RASIP1 knockdown on EC adhesion to ECM (supplemental Figures 6-9 and “Discussion”). However, in a 3-dimensional angiogenic sprouting assay recapitulating sprouting and lumen formation,30 loss of RASIP1 resulted in sprout fragmentation (Figure 4A), suggesting a deficiency in maintaining cell-cell connections. Quantification of sprout detachment showed a significant increase in RASIP1 KD HUVECs vs control (Figure 4B; supplemental Figure 10A). Time-lapse imaging of angiogenic sprouting at days 3 to 5, when lumen had already formed, showed that RASIP1 KD destabilized lumens with frequent EC-EC breakage in established sprouts (supplemental Videos 3-4). This was not a result of altered cell motility, as we observed no difference in migration of control and RASIP1 KD HUVECs in a scratch wound assay (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 10B); however, an increased number of RASIP1 KD cells detached briefly and reassembled with the migrating wavefront in the same assay (Figure 4D). The increased EC-EC detachment implied defective cell-cell adhesion, which may compromise barrier integrity. To ascertain this, we used a paracellular flux assay to measure endothelial barrier function in confluent monolayers,36 and found that passage of 40-kDa fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–dextran across the monolayer increased by ∼50% in RASIP1 KD HUVECs compared with control (Figure 4E; supplemental Figure 10C). Thus, loss of RASIP1 does not impact EC migration or ECM adhesion, but instead impairs cell-cell connectivity and barrier function leading to transient, unstable lumens.

Knockdown of RASIP1 affects EC-EC attachment. (A) Differential interference contrast images of control and RASIP1 shRNA-treated HUVECs in an angiogenic sprouting assay, 24 and 48 hours after seeding. Most sprouts have moved into the fibrin matrix yet remain attached to ECs on the bead in the control group (left), whereas a subset of sprouts detached from the beads in the RASIP1 knockdown group (arrowheads, right). Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Quantification of detached sprouts in 3 angiogenic sprouting experiments 24 and 48 hours postseeding. Twenty beads were counted per experiment. Error bars are interexperimental SEM. *P < .002 (2-way ANOVA). (C) Quantification of HUVEC migration rate (control and RASIP1 shRNA) in a scratch wound assay. (D) Quantification of the number of detached HUVECs from the leading edge in the scratch assay; 21 to 23 movies were scored per condition. (E) Relative measurement of 40-kDa FITC-dextran fluorescent signal passed across a control or RASIP1 shRNA-treated HUVEC monolayer. *P < .05 (Student t test). Error bars indicate SD for panels C-E.

Knockdown of RASIP1 affects EC-EC attachment. (A) Differential interference contrast images of control and RASIP1 shRNA-treated HUVECs in an angiogenic sprouting assay, 24 and 48 hours after seeding. Most sprouts have moved into the fibrin matrix yet remain attached to ECs on the bead in the control group (left), whereas a subset of sprouts detached from the beads in the RASIP1 knockdown group (arrowheads, right). Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Quantification of detached sprouts in 3 angiogenic sprouting experiments 24 and 48 hours postseeding. Twenty beads were counted per experiment. Error bars are interexperimental SEM. *P < .002 (2-way ANOVA). (C) Quantification of HUVEC migration rate (control and RASIP1 shRNA) in a scratch wound assay. (D) Quantification of the number of detached HUVECs from the leading edge in the scratch assay; 21 to 23 movies were scored per condition. (E) Relative measurement of 40-kDa FITC-dextran fluorescent signal passed across a control or RASIP1 shRNA-treated HUVEC monolayer. *P < .05 (Student t test). Error bars indicate SD for panels C-E.

A subset of RASIP1 localizes to nascent EC-EC junctions

Overexpressed RASIP1-GFP fusion proteins localize in large punctae in perinuclear regions and Golgi of cells.26,37 Using an antibody against endogenous RASIP1, we found that RASIP1 showed a punctate perinuclear/cytoplasmic pattern in HUVECs (Figure 5A,C). However, when we modeled nascent junction formation by destroying calcium-dependent EC-EC junctions with EGTA, followed by treatment with the cAMP analog Sp-5,6-diCl-cBiMPs,17,38,39 RASIP1 was detected at the cell periphery and overlapped with β-catenin signal, indicating junctional localization (Figure 5A-C). This signal was not seen in RASIP1 KD HUVECs (Figure 5D-F), confirming antibody specificity. In immunofluorescence of whole-mount or sections of E8.0-E8.5 mouse embryos, we observed RASIP1 at the cell periphery in the DA, in close proximity with VE-cadherin (Figure 5G-L). Thus, in cells and tissues, RASIP1 is found at newly forming or remodeling cell-cell junctions.

RASIP1 localizes to points of EC-EC contact. (A-F) Immunofluorescence staining of RASIP1 (red) in control (A-C) and RASIP1 shRNA (D-F) infected HUVECs treated with EGTA and cBiMPs, and permeabilized prior to fixation. Peripheral RASIP1 localized to the vicinity of β-catenin+ structures. (G-L) Whole-mount (G-I) or section (J-L) immunofluorescence of DA ECs from ∼E8.5 mouse embryos stained with RASIP1 (G,J, red in I,L) and VE-cadherin (H,K, green in I,L) antibodies. RASIP1 staining is often found at the cell periphery, close to VE-cadherin+ structures. Arrows indicate intracellular VE-cadherin and RASIP1 staining. Scale bars: (A-F) 20 μm; (G-L) 30 μm; (J-L) 10 μm.

RASIP1 localizes to points of EC-EC contact. (A-F) Immunofluorescence staining of RASIP1 (red) in control (A-C) and RASIP1 shRNA (D-F) infected HUVECs treated with EGTA and cBiMPs, and permeabilized prior to fixation. Peripheral RASIP1 localized to the vicinity of β-catenin+ structures. (G-L) Whole-mount (G-I) or section (J-L) immunofluorescence of DA ECs from ∼E8.5 mouse embryos stained with RASIP1 (G,J, red in I,L) and VE-cadherin (H,K, green in I,L) antibodies. RASIP1 staining is often found at the cell periphery, close to VE-cadherin+ structures. Arrows indicate intracellular VE-cadherin and RASIP1 staining. Scale bars: (A-F) 20 μm; (G-L) 30 μm; (J-L) 10 μm.

RASIP1 mediates RAP1 signaling to regulate junction assembly

Because RASIP1 is required for cell-cell adhesion and barrier function, and localizes to cell junctions, we hypothesized that RASIP1 could be regulated by factors involved in EC barrier function. This prompted us to investigate the relationship between RASIP1 and EPAC1-RAP1 signaling, a barrier strengthening pathway activated by cAMP.17 Expanding upon a report that used overexpressed RASIP1,26 we confirmed interaction between a GST-RAP1 fusion protein preloaded with GDP and endogenous RASIP1 from HUVECs (Figure 6A). This interaction was increased when GST-RAP1 was preloaded with nonhydrolyzable GTPγS (Figure 6A). We did not detect significant pulldown of RASIP1 with RHOA-GST or RAC1-GST, preloaded either with GDP or GTPγS (Figure 6A). We also did not observe significant changes in RAP1-GTP loading in RASIP1 KD HUVECs either in unstimulated or cBiMPS-treated cell lysates (Figure 6B). Taken together, the data indicate that RASIP1 acts downstream of RAP1, and could be an effector of RAP1 signaling.

RASIP1 is a RAP1 effector that controls EC junction morphology. (A) Pull-down assay using purified RAP1A, RHOA, and RAC1 GST fusion proteins with control (c) or RASIP1 shRNA (kd) HUVEC lysates. RASIP1 interacts weakly with RAP1A-GST loaded with GDP, and more strongly with RAP1A loaded with nonhydrolyzable GTPγS. No significant interaction is seen with RHOA or RAC1. (B) RAP1 activation assay with control and RASIP1 shRNA-treated HUVEC lysates. No change in RAP1A activity is seen in the unstimulated (–cBiMPs) or activated (+cBiMPs) state. (C-H) Phalloidin (C,F, green in E,H) and VE-cadherin (D,G, red in E,H) staining in control (C-E) and RASIP1 (F-H) siRNA-transfected HUVEC treated with EGTA/cBiMPs. Note the diffuse and discontinuous appearance of VE-cadherin staining in panel G, and reduced F-actin incorporation at junctions in panel F. Scale bars: 20 μm. (I-J) Actin staining (green) in control and RASIP1 KD HUVECs. Arrows indicate regions of bundled actin at the cell periphery; arrowheads show areas of diffuse or perpendicular actin at free edges. Scale bars: 20 μm. (K) Quantification of bundled actin at the cell perimeter. Each data point is an experimental replicate; each experiment comprised of 8 images with numerous free edges. *P < .05 (Student t test).

RASIP1 is a RAP1 effector that controls EC junction morphology. (A) Pull-down assay using purified RAP1A, RHOA, and RAC1 GST fusion proteins with control (c) or RASIP1 shRNA (kd) HUVEC lysates. RASIP1 interacts weakly with RAP1A-GST loaded with GDP, and more strongly with RAP1A loaded with nonhydrolyzable GTPγS. No significant interaction is seen with RHOA or RAC1. (B) RAP1 activation assay with control and RASIP1 shRNA-treated HUVEC lysates. No change in RAP1A activity is seen in the unstimulated (–cBiMPs) or activated (+cBiMPs) state. (C-H) Phalloidin (C,F, green in E,H) and VE-cadherin (D,G, red in E,H) staining in control (C-E) and RASIP1 (F-H) siRNA-transfected HUVEC treated with EGTA/cBiMPs. Note the diffuse and discontinuous appearance of VE-cadherin staining in panel G, and reduced F-actin incorporation at junctions in panel F. Scale bars: 20 μm. (I-J) Actin staining (green) in control and RASIP1 KD HUVECs. Arrows indicate regions of bundled actin at the cell periphery; arrowheads show areas of diffuse or perpendicular actin at free edges. Scale bars: 20 μm. (K) Quantification of bundled actin at the cell perimeter. Each data point is an experimental replicate; each experiment comprised of 8 images with numerous free edges. *P < .05 (Student t test).

Next, we examined the role of RASIP1 in nascent EC junctions. In the EGTA/cBiMPS-mediated barrier reformation system, junctions reassembled into linear, continuous complexes 60 minutes after cBiMPS stimulation, demonstrated by VE-cadherin staining with accompanying association of a compact belt of cortical actin (Figure 6C-E). In RASIP1 KD HUVEC, VE-cadherin was less compact and discontinuous with evidence of increased cell sliding (Figure 6F-H). To determine whether the above phenotype reflected a failure in actin bundling or linkage of actin to junctions, we examined actin at free edges of expanding cells primed to make junctional contacts, 10 minutes after cBiMPs treatment. Control cells displayed a high degree of peripheral linear actin bundles (Figure 6I), whereas RASIP1 KD reduced linear actin bundles at free edges (Figure 6J-K). We conclude that RASIP1 promotes cortical actin assembly, which impacts junction stabilization at high cell density.

RASIP1 promotes actin bundling at junctions in an EPAC1-RAP1–dependent manner

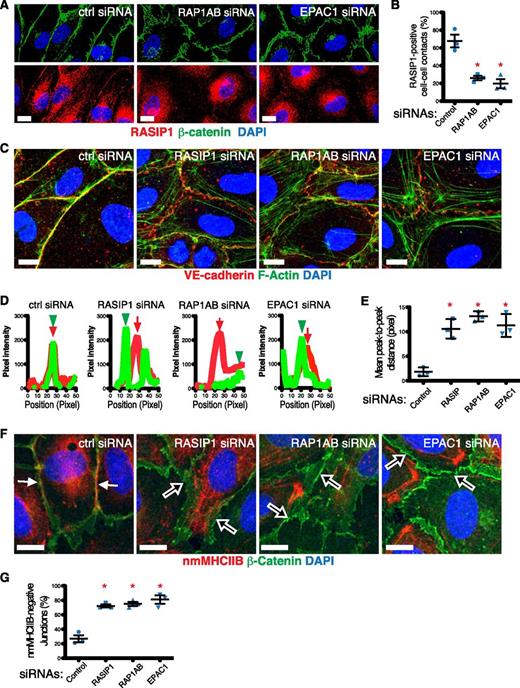

We investigated whether the role of RASIP1 in nascent junction assembly was mediated through EPAC1-RAP1 signaling. First, we tested whether EPAC1-RAP1 signaling impacted RASIP1 localization to EC-EC junctions. Knockdown of EPAC1 or RAP1A+B resulted in a decrease in the number of RASIP1+ cell-cell contacts in HUVECs treated with EGTA/cBiMPs, but did not affect global RASIP1 protein levels (Figure 7A-B; supplemental Figure 11A). Because organization of the actinomyosin cytoskeleton at junctions is important for their stabilization, and has been linked to RAP1 signaling,23,40 we compared the roles of RASIP1 with EPAC1-RAP1 in actin organization at nascent junctions. Loss of RASIP1, EPAC1, and RAP1A+B decreased compact actin at junctions while increasing actin filaments further away from junctions (Figure 7C-E), indicating RASIP1 and EPAC1-RAP1 play similar roles in this process. Because cBiMPs is a general cAMP analog, we repeated these experiments using the EPAC1-specific cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (8-pCPT),41,42 and obtained similar results (supplemental Figure 11B), implicating RASIP1 as an effector of EPAC1-RAP1 signaling. Because actin bundling at junctions requires other molecules such as nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIB (nmMHCIIB),23 we examined nmMHCIIB at junctions. Consistent with the actin organization defect, loss of RASIP1, RAP1A+B, or EPAC1 resulted in reduction of nmMHCIIB at cell-cell junctions (Figure 7F-G). Our data indicate that RASIP1 is required for EPAC1-RAP1–dependent actin organization at newly formed linear cell-cell junctions. Electron microscopy analysis of cell-cell contacts after EGTA/cBiMPs treatment revealed that RASIP1 KD HUVECs had a greater length of abnormal/wide cell-cell contacts (supplemental Figure 12), further confirming the notion that loss of RASIP1-dependent actin organization affects cell-cell junction formation.

EPAC1-RAP1–dependent junctional localization and activity of RASIP1. (A,C,F) Representative images of HUVECs transfected with the indicated siRNA were stained for RASIP1 (red) + β-catenin (green) + DAPI (blue) (A), VE-cadherin (red) + phalloidin for F-actin (green) + DAPI (blue) (C), or nmMHCIIB (red) + β-catenin (green) + DAPI (blue) (F). VE-cadherin in panel C was stained prior to permeabilization so as to capture surface signal only. (B) Loss of RAP1A+B or EPAC1 significantly reduced RASIP1 localization to cell-cell contacts. (D) Line scans perpendicular to cell-cell junctions were performed on images similar to those shown in panel C; VE-cadherin (red lines) and F-actin (green lines) signal intensities vs scan position are depicted in these representative scan data. (E) Distance between the highest peaks of F-actin signal (green arrowheads in panel D) and VE-cadherin signal (red arrows in panel D) were measured and plotted against treatment conditions. (G) Cell-cell junctions that are positive for nmMHCIIB (solid white arrows in panel F) are frequently found in control cells, whereas junctions devoid of nmMHCIIB (open white arrows in panel F) were abundant in RASIP1, RAP1A+B, and EPAC1 siRNA-treated cells. All graphs summarize data from 3 independent experiments; each data point represents mean values from 1 experiment. Thirty junctions were evaluated per condition in each experiment. Red asterisks denote statistically significant difference between the indicated groups vs control. P < .01 (unpaired Student t test). Scale bars: 10 μm. All error bars are interexperimental SEM.

EPAC1-RAP1–dependent junctional localization and activity of RASIP1. (A,C,F) Representative images of HUVECs transfected with the indicated siRNA were stained for RASIP1 (red) + β-catenin (green) + DAPI (blue) (A), VE-cadherin (red) + phalloidin for F-actin (green) + DAPI (blue) (C), or nmMHCIIB (red) + β-catenin (green) + DAPI (blue) (F). VE-cadherin in panel C was stained prior to permeabilization so as to capture surface signal only. (B) Loss of RAP1A+B or EPAC1 significantly reduced RASIP1 localization to cell-cell contacts. (D) Line scans perpendicular to cell-cell junctions were performed on images similar to those shown in panel C; VE-cadherin (red lines) and F-actin (green lines) signal intensities vs scan position are depicted in these representative scan data. (E) Distance between the highest peaks of F-actin signal (green arrowheads in panel D) and VE-cadherin signal (red arrows in panel D) were measured and plotted against treatment conditions. (G) Cell-cell junctions that are positive for nmMHCIIB (solid white arrows in panel F) are frequently found in control cells, whereas junctions devoid of nmMHCIIB (open white arrows in panel F) were abundant in RASIP1, RAP1A+B, and EPAC1 siRNA-treated cells. All graphs summarize data from 3 independent experiments; each data point represents mean values from 1 experiment. Thirty junctions were evaluated per condition in each experiment. Red asterisks denote statistically significant difference between the indicated groups vs control. P < .01 (unpaired Student t test). Scale bars: 10 μm. All error bars are interexperimental SEM.

We then used EPAC1 agonists to further investigate the effect of RAP1 signaling on sprouting, migration, and permeability. Treatment of control HUVECs with 8-pCPT suppressed the basal level of sprout detachment in control cells but did not change the increased fragmentation in RASIP1 KD sprouts (supplemental Figure 10A). In the scratch wound migration assay, treatment of control and RASIP1 KD HUVEC with either cBiMPs or 8-pCPT had no effect on migration rates (supplemental Figure 10B), indicating that this pathway does not impact cell migration. In the permeability assay, 8-pCPT suppressed basal permeability, whereas RASIP1 KD increased basal permeability and abolished the effect of 8-pCPT (supplemental Figure 10C), indicating that RASIP1 acts downstream of EPAC1-RAP1 to control EC integrity.

To ascertain the physiological significance of our findings, we also found that loss of RASIP1 compromised EC barrier function when HUVECs were stimulated by 2 known physiological regulators of permeability: thrombin (a negative regulator) and Angiopoietin-1 (a positive regulator) (supplemental Figure 13).

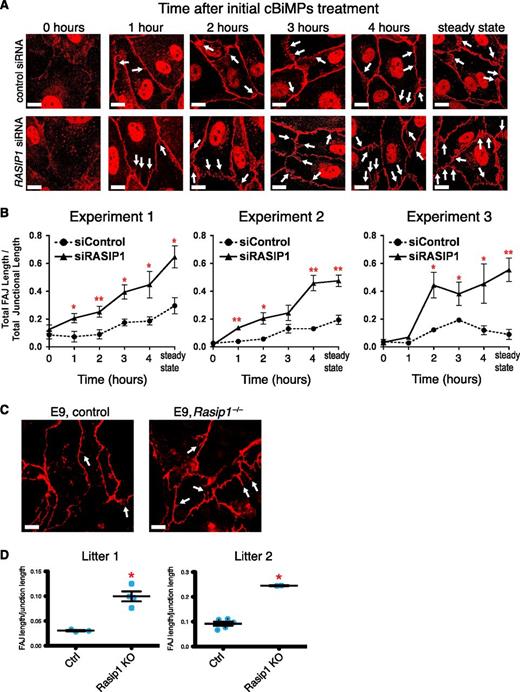

RASIP1 restricts junction remodeling

To understand the consequences of loss of RASIP1 on junction dynamics, we examined junction morphology in a time course after EGTA/cBiMPs treatment. Remodeling junctions display an immature, zipperlike morphology, with intracellular protrusions of VE-cadherin aligned with actin stress fibers, termed discontinuous or focal AJs (FAJs).43,44 We quantified FAJs, and found that the total length of FAJs relative to total linear junction length increased more rapidly in RASIP1 KD HUVECs after EGTA/cBiMPS treatment, and was consistently higher in steady-state culture, suggesting that loss of RASIP1 increases junction remodeling (Figure 8A-B). This difference was also recapitulated in vivo, as Rasip1−/− yolk sacs displayed increased endothelial FAJ/junction ratios when compared with control animals (Figure 8C-D). We also overexpressed constitutively active RAP1 (RAP1A-G12V-RFP) in control and RASIP1 KD HUVECs and examined the effects on FAJ formation. RAP1A-G12V+ cells had a reduced FAJ/junction ratio when compared with RAP1A-G12V− cells, and loss of RASIP1 reversed this effect (supplemental Figure 14), further confirming the essential role of RASIP1 downstream of RAP1.

Loss of RASIP1 increases junction remodeling. (A) Time course of FAJ formation after EGTA treatment and cBiMPs stimulation. In control cells stained with VE-cadherin, linear junctions decay into an equilibrium of linear and FAJs (white arrows indicate a subset of FAJs). In RASIP1 KD HUVECs, FAJs appear earlier (∼1-2 hours post-cBiMPs) and accumulate more rapidly, culminating in an increased proportion of FAJs at steady state. (B) Quantification of FAJ/linear junction ratios in 3 experiments. (C) Whole-mount immunofluorescence staining of VE-cadherin in control and Rasip1−/− yolk sacs at E9. FAJs (white arrows) are increased in knockout yolk sacs, mirroring the in vitro finding. (D) Quantification of FAJ/linear junction ratios in yolk sacs from 2 separate litters of E9 embryos. Litter 1: n = 3 control, 4 Rasip1−/− embryos. Litter 2: n = 5 control, 2 Rasip1−/− embryos. Red asterisks denote statistical significance vs control groups. P < .01 (unpaired Student t test). Scale bars: 10 μm.

Loss of RASIP1 increases junction remodeling. (A) Time course of FAJ formation after EGTA treatment and cBiMPs stimulation. In control cells stained with VE-cadherin, linear junctions decay into an equilibrium of linear and FAJs (white arrows indicate a subset of FAJs). In RASIP1 KD HUVECs, FAJs appear earlier (∼1-2 hours post-cBiMPs) and accumulate more rapidly, culminating in an increased proportion of FAJs at steady state. (B) Quantification of FAJ/linear junction ratios in 3 experiments. (C) Whole-mount immunofluorescence staining of VE-cadherin in control and Rasip1−/− yolk sacs at E9. FAJs (white arrows) are increased in knockout yolk sacs, mirroring the in vitro finding. (D) Quantification of FAJ/linear junction ratios in yolk sacs from 2 separate litters of E9 embryos. Litter 1: n = 3 control, 4 Rasip1−/− embryos. Litter 2: n = 5 control, 2 Rasip1−/− embryos. Red asterisks denote statistical significance vs control groups. P < .01 (unpaired Student t test). Scale bars: 10 μm.

Mechanism of RASIP1-dependent junction stabilization is distinct from KRIT1

Because EPAC-RAP1 signaling uses multiple downstream factors, we compared the effect of RASIP1 KD with loss of KRIT1, a RAP1 effector reported to play a role in junctional stability through suppression of RHOA activity.45 In the EGTA/cBiMPs assay, KRIT1 siRNA caused actin to shift away from junctions, similar to RASIP1 siRNA (supplemental Figure 15A). However, unlike KRIT1 KD, RASIP1 siRNA did not increase myosin light chain phosphorylation (supplemental Figure 15B). RASIP1 KD also does not alter global RHOA activity (supplemental Figure 16). Our data indicate that the EPAC1-RAP1 pathway uses multiple effectors to exert related but not identical functions (supplemental Figure 17).

Discussion

Vascular lumen formation and expansion is a complex process, and the major molecular regulators are emerging.2,5,6,46,47 Previous work indicated that Rasip1 is essential for de novo vascular lumen formation in all mouse blood vessels, a consequence of its role in defective EC-ECM adhesion.24 Using a similar mouse knockout of Rasip1, we show that patent lumens form in many types of vessels. Lumen size of Rasip1−/− DAs is variable, but ∼80% of samples met the criterion of a patent lumen.2 Primitive erythrocytes were observed in many sections of the DA after the onset of circulation, and in sites of vascular dilation or rupture at E9.0, prior to the known onset of definitive hematopoiesis in the mouse embryo.31 Furthermore, loss of rasip1 in zebrafish does not significantly impact lumen formation or initial circulation, but causes vascular leak and hemorrhage. We propose that the lumens in Rasip1−/− embryonic vessels are unstable, but support passage of blood cells from the yolk sac blood islands to the embryo. Thus, Rasip1 is crucial for maintaining the integrity of a developing and expanding vascular network. It is worth noting that our Rasip1 knockout resembles VE-cadherin (Cdh5) and Tie2 mutant mice.16,48-50 In these animals, vessels form and acquire lumen, but do not undergo stable remodeling and exhibit disrupted integrity. Our results reinforce the notion that disruption of the linkage between endothelial junctions and the cytoskeleton does not prevent assembly and lumenization, but leads to vascular disintegration. The reason for the disparity in our observations and the previous report is unknown, but may be a consequence of different genetic backgrounds used in the 2 studies.

Our in vivo observations are corroborated by several in vitro observations. First, RASIP1-deficient sprouts form transient and unstable lumens in a sprouting angiogenesis assay.30 Second, loss of RASIP1 causes an increase in paracellular flux across a confluent HUVEC monolayer. Third, analysis of RASIP1 localization showed that a subset of the RASIP1 protein pool translocates to cell junctions upon activation of EPAC1-RAP1 signaling, a known pathway involved in strengthening endothelial barrier function.17,18 Fourth, loss of RASIP1 causes defects in actin bundling at junctions, indicating that RASIP1 impacts cytoskeletal-junctional architecture. Fifth, RASIP1 promotes junction maturation by suppressing junction remodeling. EPAC1-RAP1 signaling is critical for stabilization of junctions, and it does so through signaling to effector proteins involved in cytoskeletal and junctional regulation.17,18 The role of RASIP1 in endothelial junctions appears to be as an effector of this pathway, and trafficking of RASIP1 and binding partners may modulate actin and junction dynamics to control stability (supplemental Figure 17). Further work will be required to elucidate the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which RASIP1 stabilizes endothelial junctions, and the relationship between RASIP1 and other RAP1 effectors such as KRIT1.

In summary, the data reported in this study show an essential role for Rasip1 in the maintenance of embryonic vessel stability. We propose that Rasip1 acts downstream of lumenogenesis, and plays a requisite role in maintaining stability of newly formed blood vessels, through control of actin linkages to newly established EC-EC junctions. These studies lay the groundwork for investigating the role of Rasip1 in vascular pathologies, and we anticipate that activation of EPAC1-RAP1-RASIP1 signaling may have protective effects in diseases with altered vascular barrier function that lead to edema and hemorrhage, such as sepsis, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy.

Note added in proof

While this paper was in review, additional data describing the role of RASIP1 as an EPAC1–RAP1 effector in endothelial barrier function were reported by Post et al.51

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank L. Komuves for microscopy support, S. van Dijk for preparation of materials for electron microscopy, J. Chen, J. Burton, S. Yang, S. Scales, M. Solloway, and D. Grant-Wilson for technical advice and assistance, and A. Durnal, K. Feger, M. Garcia, and A. Wong for animal husbandry. The authors are grateful to M. Bedley (Nikon) and Dr M. Paddy (UC-Davis MCB Microscopy Core) for use of structured illumination microscopy facilities.

Authorship

Contribution: C.W.W., L.H.P., J.K., P.S.C., and W.Y. designed the study; C.W.W. and W.Y. wrote the manuscript; C.W.W., L.H.P., C.J.H., T.S., J.M., G.P., A.D.M., and P.V. performed the experiments; S.W., M.R.-G., and W.Y. designed and created the Rasip1 knockout mouse line; and M.S., C.C., and A.C. contributed technical expertise, image processing, and image analysis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.W.W., T.S., J.M., M.S., C.C., P.V., A.C., S.W., M.R.-G., and W.Y. are employees of Genentech, Inc., a member of the Roche group. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for L.H.P. is Solazyme, Inc., South San Francisco, CA 94080.

Correspondence: Weilan Ye, Department of Molecular Biology, Genentech, Inc, 1 Dna Way, South San Francisco, CA 94080; e-mail: loni@gene.com.