In this issue of Blood, Neven et al report that a third of the patients with interleukin-10 receptor (IL-10R) deficiency develop B-cell lymphomas in the first decade of their life. The lymphomas uniformly contained amplifications of c-rel, activation of inflammatory nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) target genes, and a defective intratumoral CD8+ T-cell tumor immunosurveillance.1

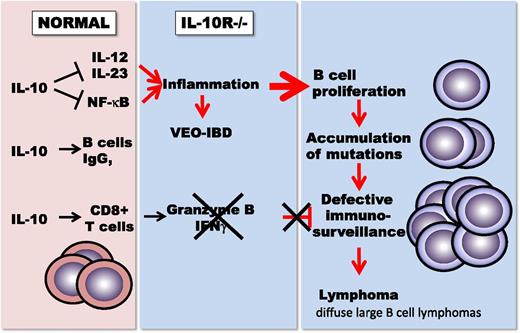

IL-10 balances proinflammatory immune regulation against the stimulation of CD8+ T-cell–mediated immunity and immunoglobulin G (IgG) production in B cells. In the absence of IL-10 receptors, patients with very-early-onset IBD suffer from severe childhood colitis. The absence of CD8+ T-cell–mediated immunosurveillance leads to the development of diffuse large B cell lymphomas.

IL-10 balances proinflammatory immune regulation against the stimulation of CD8+ T-cell–mediated immunity and immunoglobulin G (IgG) production in B cells. In the absence of IL-10 receptors, patients with very-early-onset IBD suffer from severe childhood colitis. The absence of CD8+ T-cell–mediated immunosurveillance leads to the development of diffuse large B cell lymphomas.

IL-10 is an immune regulatory cytokine with anti-inflammatory properties but stimulatory functions on B cells and CD8+ T cells. However, because of its anti-inflammatory properties, IL-10 is frequently considered an immune-suppressive and tumor-promoting cytokine. To complicate the picture, IL-10 enhances the proliferation and survival of the differentiation, the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) molecules, immunoglobulins, and isotype switching in B cells. Therefore, IL-10 has been considered to promote the development of B-cell lymphomas.2

Two seemingly opposing functions in immune regulation were independently ascribed to IL-10 with its discovery in 1990, first B-cell–derived T-cell growth factor (B-TCGF),3 and secondly the cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor.4

As a B-TCGF, IL-10 induces the expression of CD3 and CD8 on adult thymocytes and consequently the proliferation of those cells. Further studies showed that IL-10 induced not only the proliferation but also the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells. Treatment of mouse tumor models with recombinant human IL-10 or expression of IL-10 in tumor cells led to tumor inhibition and rejection, with CD8+ T cells being essential for the tumor rejection. Genetic deficiency of IL-10 in mice (IL-10−/− mice) leads to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and to the development of colon carcinoma.5 Mice expressing elevated levels of IL-10 are resistant to tumor induction by carcinogens, with enhanced CD8+ T-cell infiltration and expression of antigen-presenting molecules (MHC molecules) in the premalignant tissues.6 IL-10 directly induces cytotoxic effector molecules and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) in CD8+ T cells, both in vitro and within the tumor tissue. CD8 T-cell–derived IFN-γ induces the upregulation of MHC molecules within the tumor, allowing increased immune recognition of tumor-associated antigen. Conjugation of polyethylene glycol (PEG) to IL-10 allowed a permanent elevation of IL-10 levels in mice.

As cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor, IL-10 suppresses the expression of the shared p40 subunit of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IL-23 and directly and indirectly inhibits the activation of the proinflammatory transcription factor NF-kB. Subsequently, IL-12–mediated induction of IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor alpha in Th1-polarized CD4 helper cells and IL-23–driven IL-17 expression of Th17 cells is diminished. Both helper cell subpopulations play essential roles in a variety of human inflammatory diseases, and their mouse models. IL-10−/− mice and IL-10R−/− mice develop IBD and are particularly sensitized for the induction of autoinflammatory diseases. Interestingly, the propensity toward enhanced inflammation in IL-10−/− mice results in enhanced tumor rejection, when toll-like receptor ligands are injected into or around a tumor.7 These observations and the inhibition of IL-12 expression by IL-10 led to a call for the development of IL-10–inhibiting antibodies for cancer immune therapy by tumor immunologists.8 However, immune-mediated inflammatory responses are also thought to promote tumor growth and subdue cytotoxic T-cell responses to tumors.9

Although adult human IBD is not linked to a known genetic defect in the IL-10 pathway, the treatment of patients with Crohn’s disease with recombinant IL-10 led to clinical improvement. Closing the species gap between mice and humans, genetic mutations in IL-10R were recently found in 4 of patients with very-early-onset IBD, a severe genetic form of colitis that develops within the first years of life.10 Neven et al now report that one-third of these patients also develop B-cell lymphomas at an early age.1 The lymphomas that share many characteristics with diffuse large B-cell lymphomas were not associated with the intestinal inflammation but developed spontaneously at different body sites. Genetic amplification of the c-Rel oncogene activated many of the NF-kB–driven proinflammatory genes, in particular the toll-like receptor signaling pathway, a pathway normally subdued by IL-10. Remarkably, immunosurveillance was almost absent within the tumor, with rare tumor-infiltrating T cells, low CD3 and CD8 expression, and the complete absence of the cytotoxic T-cell effector molecule granzyme B. These findings are the first direct genetic evidence for the convergence of the diverse tumor inhibitory functions of IL-10 and for the dependence of tumor immunosurveillance on IL-10 in humans.

The IL-10 receptor is expressed only on hematopoietic cells and, in particular, on cells of the immune system. Neven et al consequently report that several patients treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are in remission since hematopoietic stem cell transplantation would restore tumor immunosurveillance.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.O. is an employee of ARMO BioSciences, Redwood City, CA.