Key Points

77% of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma have functional abnormalities of A20.

A20 inactivation plays a key role in lymphomagenesis in the context of autoimmunity.

Abstract

Several autoimmune diseases, including primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS), are associated with an increased risk for lymphoma. Polymorphisms of TNFAIP3, which encodes the A20 protein that plays a key role in controlling nuclear factor κB activation, have been associated with several autoimmune diseases. Somatic mutations of TNFAIP3 have been observed in the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma subtype frequently associated with pSS. We studied germline and somatic abnormalities of TNFAIP3 in 574 patients with pSS, including 25 with lymphoma. Nineteen additional patients with pSS and lymphoma were available for exome sequence analysis. Functional abnormalities of A20 were assessed by gene reporter assays. The rs2230926 exonic variant was associated with an increased risk for pSS complicated by lymphoma (odds ratio, 3.36 [95% confidence interval, 1.34-8.42], and odds ratio, 3.26 [95% confidence interval, 1.31-8.12], vs controls and pSS patients without lymphoma, respectively; P = .011). Twelve (60%) of the 20 patients with paired germline and lymphoma TNFAIP3 sequence data had functional abnormalities of A20: 6 in germline DNA, 5 in lymphoma DNA, and 1 in both. The frequency was even higher (77%) among pSS patients with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Some of these variants showed impaired control of nuclear factor κB activation. These results support a key role for germline and somatic variations of A20 in the transformation between autoimmunity and lymphoma.

Introduction

A20, encoded by TNFAIP3 on chromosome 6, is an ubiquitin-editing enzyme that plays a central role in the control of nuclear factor κB (NF-kB) activation. This enzyme is expressed in most cell types at low basal levels but is rapidly induced on tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-or Toll-like receptor-mediated NF-kB activation. Once expressed, A20 acts as a negative feedback regulator of NF-kB activation via its ovarian tumor and zinc finger domains and is a central regulator of inflammation; A20 knockout mice die during the neonatal period as a result of severe, uncontrolled inflammation leading to cachexia.1,2

Genomewide association studies have demonstrated associations between TNFAIP3 polymorphisms and risk for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), systemic sclerosis, and other autoimmune diseases.3,4 Many of these studies demonstrated an association with an exonic single nucleic polymorphism (SNP), rs2230926, located in exon 3 and leading to replacement of phenylalanine by cysteine at amino acid position 127 (rs2230926 T>G; F127C).5

In addition to its role in autoimmunity, A20 inactivation in tumor cells has been found in a number of lymphomas, particularly the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type of marginal zone lymphoma.4,6-9 In accordance with the well-established role of excessive NF-kB activation in the development of lymphoid malignancies,10 A20/TNFAIP3 is considered a potent tumor suppressor gene in B-cell lymphoma.

Several autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, and primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS), are associated with an increased risk for malignant lymphoma, presumably related to the underlying chronic inflammatory process.11 pSS is a prototypic autoimmune disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of salivary and lacrimal glands leading to xerostomia and xerophtalmia. Chronic polyclonal B-cell activation is commonly present, which may explain why this autoimmune disease has the strongest association with the development of B-cell lymphoma (relative risk, 15-20). Most lymphomas in pSS are typically localized in the salivary glands, the target organs of pSS, and more generally, the extranodal MALT.

Given the relevance of A20 to both autoimmunity and lymphomagenesis, we studied germline and somatic abnormalities of TNFAIP3 among a well-characterized cohort of pSS patients, some of whom had also developed lymphoma.

Patients and methods

Patients and lymphoma samples

Two French cohorts of pSS patients were studied: the prospective Assessment of Systemic Signs and Evolution of Sjögren's Syndrome (ASSESS) cohort (programme hospitalier de recherche clinique 2006-AOM06133) and the cohort of pSS patients followed-up in the Department of Rheumatology, Hôpitaux Universitaires Paris-Sud. The ASSESS cohort members were recruited between 2006 and 2008; the Paris-Sud cohort members were recruited between 2000 and 2010. An additional 19 patients with pSS and lymphoma were available for the TNFAIP3 exome sequencing analyses. These patients were recruited as part of the French multicenter pSS network (15 centers), which was created in 2002 for conducting randomized controlled studies (infliximab, rituximab, hydroxychloroquine) in this disease. All patients fulfilled the American-European Consensus Group criteria for pSS.12 Controls were selected from a population of French healthy blood donors.

Lymphomas were classified according to the current World Health Organization classification.13

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Germline DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Lymphoma DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tumor tissues (supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site).

Genotyping

Three SNPs within the TNFAIP3 gene region that have been associated with SLE among individuals of European ancestry5 were genotyped from germline DNA. rs2230926 is located in exon 3, and rs13192841 and rs6922466 map to within 250 kb upstream and downstream of the TNFAIP3 region, respectively. Genotyping employed a predesigned TaqMan assay from Applied Biosystems (assay 26882391-1), using a competitive allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system (KASpar genotyping; www.lgcgenomics.com/), as previously described.14 All participants were also genotyped for 48 ancestry informative markers (AIMs), selected to be highly informative for continental ancestry15 (list available on request), to identify genetic outliers and adjust for population stratification (see Statistical methods). A subset of 328 cases were genotyped and passed quality control for the Immunochip marker set,16 which was used for sensitivity analyses comparing pSS patients with and without lymphoma with the larger marker set for ancestry determination provided by the Immunochip.

TNFAIP3 exon sequencing

Sequencing of the 8 coding exons (2-9) of the TNFAIP3 gene, as well as exon/intron junctions, exon 1 (which is not coding), part of intron 5, and part of the 3′ intronic region, was performed on germline and lymphoma DNA using the Sanger method (supplemental Methods). All SNPs, mutations, or losses of heterozygosity identified by Sanger sequencing were confirmed by pyrosequencing methods (supplemental Methods).

Measurement of TNFAIP3 mRNA level by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

RNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). The Enhanced Avian HS reverse-transcription PCR kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for the reverse transcription of messenger RNA (mRNA) into complementary DNA, and then quantitative PCR was performed using FastStart SYBR Green Master (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (supplemental Methods).

Functional analysis of wild-type (WT) and A20 mutants

The pGL4.32 (luc2P/NF-kB-RE/Hygro) plasmid (Promega), which drives luciferase expression in response to NF-kB activation, was used as a reporter gene system (supplemental Methods) to assess the function of the identified abnormalities of TNFAIP3. Two mutated sequences of TNFAIP3 were tested: one containing the rs2230926 minor allele resulting in the p.F127C A20 variant and the second containing an insertion of two guanines at position 138196024 (exon 3) leading to a 122-amino acid truncated protein instead of a 790-amino acid protein (supplemental Methods).

Statistical methods

To identify ancestry outliers and adjust for population structure, principal components analysis (PCA) of 47 AIMs was performed using EIGENSTRAT software.17 Participants were removed if they were outside of 4 standard deviations for the top two principal components (PCs) or had self-reported non-European ancestry; the top two PCs were also used to adjust for any residual ancestry differences. Case-control association tests were performed for TNFAIP3 SNPs, using single SNP logistic regression analyses in PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/), assuming an additive model and including the first two PCs as covariates. Because of the relatively low number of AIMs and the low frequency of the lymphoma phenotype in pSS, we also performed a sensitivity analysis on a subset of cases genotyped on the Immunochip platform.16 An additional PCA was performed with 3410 independent (r2 < 0.2) Immunochip markers, and a homogeneous cluster of patients was identified. Case-only associations (ie, pSS patients with vs without lymphoma) were retested both with Fisher’s exact test and with logistic regression, adjusting for the top two Immunochip PCs. Differences in lymphoma histologic type were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. Differences in transfection experiments were assessed using unpaired t tests.

Results

Characteristics of patients

Patients with pSS.

Five hundred seventy-four patients with pSS were studied, including 335 (57%) with anti-SSA antibodies, 176 (30%) with both anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies, and 307 (52%) with previous or current systemic complications, including skin, muscular, articular, renal, or neurological involvement and/or history of lymphoma.

Patients with pSS and lymphoma.

A total of 44 patients with pSS and lymphoma were studied, including 25 in the initial genetic association analyses (discovery set) and 19 additional patients available for TNFAIP3 exome sequencing of both germline and somatic DNA. Individual characteristics of the 44 patients with lymphoma are presented in supplemental Table 1.

The most frequent histologic type was MALT lymphoma, which occurred in 28 (63.6%) of 44 patients and was primarily identified in the parotid glands (14/28, 50%), with others localized to the salivary glands (4/28, 14.2%), cavum (3/28, 10.7%), stomach (2/28, 7%), lung (2/28, 7%), skin (1/28, 3.5%), ocular adnexal (1/28, 3.5%), and thymus (1/28, 3.5%). Seven (25%) patients with MALT lymphoma presented with disseminated disease (stage IV), and 21 (75%) with localized disease (stage IE). There were 4 patients with nodal marginal zone lymphoma, 2 with splenic marginal zone lymphoma, 1 with follicular lymphoma, and 1 with lymphocytic lymphoma. Five patients presented with a high-grade diffuse large-cell lymphoma. One patient each presented with Hodgkin’s and T-cell lymphoma (fungoid mycosis). One patient with a history of immunosuppressive treatment with azathioprine and methotrexate had an Epstein-Barr virus-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder.

The rs2230926 SNP is associated with the development of lymphoma in pSS patients.

For the initial genetic association study, a total of 574 independent pSS cases, including 25 with lymphoma, and 451 independent controls were analyzed for the 3 TNFAIP3 SNPs and 47 AIMs (a single AIM failed genotyping and was dropped from further analysis). PCA of the AIMs using EIGENSTRAT17 identified 79 population outliers; a total of 97 participants were removed, including 18 individuals removed as a result of self-reported non-European ancestry (supplemental Figure 1A).

We did not observe an association at a significance level of P < .05 between these 3 SNPs and pSS (Table 1); however, we had low power (<25%) for the observed effect size (OR, 1.26). Similarly, these SNPs were not associated (at P < .05) with the presence of autoantibodies (anti-SSA, or anti-SSA + anti-SSB) or with the occurrence of systemic involvement (Table 2) when compared with control patients. For these analyses, we had approximately 38% to 60% power for the observed ORs (OR, 1.54 and 1.66, respectively).

Association testing of the 3 TNFAIP3 SNPs among patients with pSS and control patients

| SNP . | Number of minor alleles (%) . | All pSS vs controls . | Lymphoma+ pSS vs controls . | Lymphoma− pSS vs controls . | Lymphoma+ pSS vs lymphoma− pSS . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (N = 451) . | All pSS patients (N = 574) . | pSS patients without lymphoma (N = 549) . | pSS patients with lymphoma (N = 25) . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | |

| rs13192841 | 243 (28) | 313 (28) | 298 (27) | 15 (30) | 0.94 | .52 | 1.0 | .94 | 0.93 | .50 | 1.12 | .72 |

| rs2230926 | 55 (6) | 73 (6) | 66 (6) | 7 (15) | 1.26 | .24 | 3.36 | .01 | 1.18 | .41 | 3.26 | .011 |

| rs6922466 | 220 (25) | 283 (25) | 272 (25) | 11 (22) | 0.99 | .91 | 0.81 | .56 | 1.0 | .98 | 0.84 | .6 |

| SNP . | Number of minor alleles (%) . | All pSS vs controls . | Lymphoma+ pSS vs controls . | Lymphoma− pSS vs controls . | Lymphoma+ pSS vs lymphoma− pSS . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (N = 451) . | All pSS patients (N = 574) . | pSS patients without lymphoma (N = 549) . | pSS patients with lymphoma (N = 25) . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | |

| rs13192841 | 243 (28) | 313 (28) | 298 (27) | 15 (30) | 0.94 | .52 | 1.0 | .94 | 0.93 | .50 | 1.12 | .72 |

| rs2230926 | 55 (6) | 73 (6) | 66 (6) | 7 (15) | 1.26 | .24 | 3.36 | .01 | 1.18 | .41 | 3.26 | .011 |

| rs6922466 | 220 (25) | 283 (25) | 272 (25) | 11 (22) | 0.99 | .91 | 0.81 | .56 | 1.0 | .98 | 0.84 | .6 |

Association testing among control patients, all patients with pSS, and patients with patients without lymphoma or with lymphoma using logistic regression adjusting for top 2 PCs of ancestry informative markers. Significant figures are in bold. OR, odds ratio.

Association testing among control patients, patients with pSS with anti Sjögren's Syndrome A+ (SSA+), pSS patients with anti SSA and anti SSB+, and patients with pSS with systemic manifestations using logistic regression adjusting for top 2 PCs of AIMs

| SNP . | Number of minor alleles (%) . | SSA+ pSS vs controls . | SSA+ and SSB+ pSS vs controls . | Systemic pSS vs controls . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (N = 451) . | Anti SSA+ (N = 335) . | Anti SSA+ and SSB+ (N = 176) . | Systemic manifestations (N = 307) . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | |

| rs13192841 | 243 (28) | 183 (27) | 94 (27) | 166 (27) | 0.92 | .5 | 0.89 | .42 | 0.93 | .57 |

| rs2230926 | 55 (6) | 49 (7) | 26 (8) | 43 (7) | 1.54 | .051 | 1.66 | .06 | 1.39 | .15 |

| rs6922466 | 220 (25) | 165 (25) | 82 (24) | 166 (27) | 0.99 | .95 | 0.91 | .54 | 1.11 | .39 |

| SNP . | Number of minor alleles (%) . | SSA+ pSS vs controls . | SSA+ and SSB+ pSS vs controls . | Systemic pSS vs controls . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (N = 451) . | Anti SSA+ (N = 335) . | Anti SSA+ and SSB+ (N = 176) . | Systemic manifestations (N = 307) . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | |

| rs13192841 | 243 (28) | 183 (27) | 94 (27) | 166 (27) | 0.92 | .5 | 0.89 | .42 | 0.93 | .57 |

| rs2230926 | 55 (6) | 49 (7) | 26 (8) | 43 (7) | 1.54 | .051 | 1.66 | .06 | 1.39 | .15 |

| rs6922466 | 220 (25) | 165 (25) | 82 (24) | 166 (27) | 0.99 | .95 | 0.91 | .54 | 1.11 | .39 |

However, the rs2230926G variant was significantly associated with the development of lymphoma in pSS patients (OR, 3.26; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31-8.12; P = .011 compared with pSS patients without lymphoma; and OR, 3.36; 95% CI, 1.34-8.42; P = .0097 compared with healthy control patients; Table 1). Conversely, there was no association between the rs2230926G variant and the risk for pSS among patients without lymphoma (OR, 1.18; P = .41). In a sensitivity analysis of patients with 3410 independent Immunochip markers, a genetically homogeneous cluster was identified by removing 57 PCA outliers (supplemental Figure 1B); 13 patients with lymphoma and 258 without were retained for this analysis. Our results were confirmed in this subset using both logistic regression adjusted for the Immunochip PCs (OR, 8.1; 95% CI, 2.1-31.3; P = .002) and using Fisher’s exact test to account for small sample sizes (OR, 5.5; 95% CI, 1.2-18.8; P = .013) (Table 3).

Results of sensitivity analyses comparing patients with pSS with and without lymphoma among the subset of pSS cases with Immunochip data, using logistic regressions adjusting for top 2 Immunochip PCs and using Fisher’s exact test

| SNP . | Number of minor alleles (%) . | Logistic regression with PC1, PC2 . | Exact test . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pSS patients without lymphoma (N = 258) . | pSS patients with lymphoma (N = 13) . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | |

| rs13192841 | 144 (28) | 9 (35) | 1.47 | .37 | 1.36 | .5 |

| rs2230926 | 18 (4) | 4 (17) | 8.1 | .002 | 5.5 | .013 |

| rs6922466 | 132 (26) | 3 (12) | 0.38 | .13 | 0.38 | .16 |

| SNP . | Number of minor alleles (%) . | Logistic regression with PC1, PC2 . | Exact test . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pSS patients without lymphoma (N = 258) . | pSS patients with lymphoma (N = 13) . | OR . | P . | OR . | P . | |

| rs13192841 | 144 (28) | 9 (35) | 1.47 | .37 | 1.36 | .5 |

| rs2230926 | 18 (4) | 4 (17) | 8.1 | .002 | 5.5 | .013 |

| rs6922466 | 132 (26) | 3 (12) | 0.38 | .13 | 0.38 | .16 |

TNFAIP3 germline abnormalities in pSS patients with lymphoma

Frequency of the rs2230926 polymorphism.

Among the 43 patients with pSS and lymphoma who underwent TNFAIP3 sequencing of germline DNA, the rs2230926G risk variant was present in 11 (26%) (OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.210-5.230; P = .017 compared with pSS patients without lymphoma [12%, 66/549]; and OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.204-5.307; P = .018 compared with controls [12%, 55/451]).

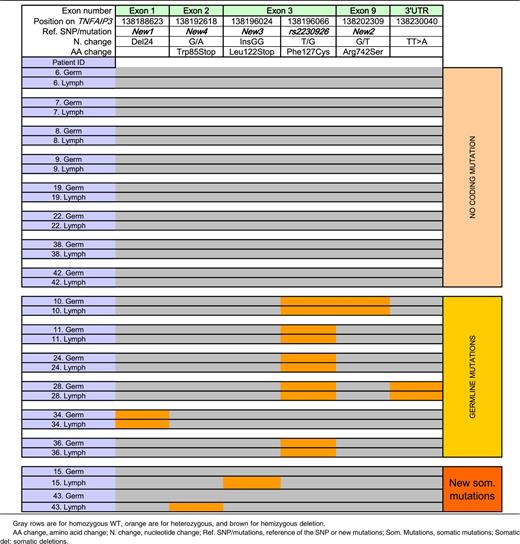

Novel TNFAIP3 germline abnormalities (Figure 1 and Table 4).

We also identified a novel 24-bp deletion (CCCGGAGAGGTAACCGCCGCGCCT/-) in exon 1 (termed New 1), which results in suppression of a potential Sp1 binding site within the promoter. This deletion occurred in 4 patients, 2 of whom also had the rs2230926G allele. In another patient with rs2230926G, we identified a novel variant within exon 9 (Arg742Ser), termed New 2. Last, we studied the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide located in the 3′ untranslated region that was recently reported to be associated with risk for SLE and is in strong linkage disequilibrium with rs2230926G.18 We observed the TT>A variant in 5 patients, all of whom had the rs2230926G allele; however, an additional 6 patients had the rs2230926G without the TT>A variant. Thus, these variants are in complete linkage disequilibrium (D′ = 1) but not perfectly correlated (r2 < 1.0).

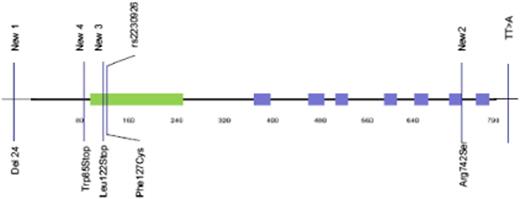

Location of germline and somatic mutations of TNFAIP3 on the A20 protein. The green zone represents the ovarian tumor domain; the blue zones represent zinc finger domains. Four germline and potential coding mutations of TNFAIP3 were identified among pSS and lymphoma patients. Two of them have already been described: rs2230926, consisting of the substitution of a thymine with a guanine, resulting in the Cys127 protein, and the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide located in 3′ untranslated region. We described 2 new mutations: a deletion of 24 bp in exon 1 (New 1) and a substitution of guanine with thymine in exon 9, resulting in the 742Ser protein (New 2). Two new and potential coding mutations of TNFAIP3 were identified among lymphoma sequences. New 3 corresponds to the insertion of 2 guanines in exon 3, leading to a truncated protein (Stop122). New 4 is a guanine to adenine mutation in exon 2 (New 4), leading to a stop codon at position 85.

Location of germline and somatic mutations of TNFAIP3 on the A20 protein. The green zone represents the ovarian tumor domain; the blue zones represent zinc finger domains. Four germline and potential coding mutations of TNFAIP3 were identified among pSS and lymphoma patients. Two of them have already been described: rs2230926, consisting of the substitution of a thymine with a guanine, resulting in the Cys127 protein, and the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide located in 3′ untranslated region. We described 2 new mutations: a deletion of 24 bp in exon 1 (New 1) and a substitution of guanine with thymine in exon 9, resulting in the 742Ser protein (New 2). Two new and potential coding mutations of TNFAIP3 were identified among lymphoma sequences. New 3 corresponds to the insertion of 2 guanines in exon 3, leading to a truncated protein (Stop122). New 4 is a guanine to adenine mutation in exon 2 (New 4), leading to a stop codon at position 85.

TNFAIP3 abnormalities among 20 patients with both germline and somatic sequences available: patients without coding mutation or with germline or somatic mutations of TNFAIP3

To summarize, 13 (30%) of 43 pSS patients with lymphoma studied had a potentially functional germline abnormality of A20: 11 with the rs2230926G variant resulting in Phe/Cys at amino acid position 127 (2 with and 2 without the exon 1 24-bp deletion resulting in suppression of a Sp1 binding site), and 2 without rs2230926G but with the exon 1 24-bp deletion (Figure 1 and Table 1).

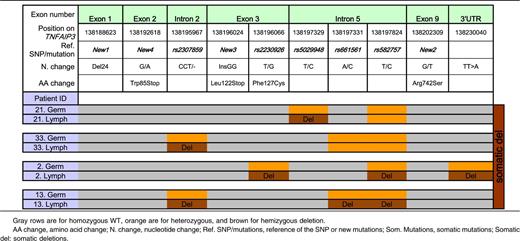

TNFAIP3 lymphoma abnormalities in pSS patients with lymphoma

Lymphoma samples were obtained from 34 of 44 patients. High-quality DNA was available for 21 of these patients, all but 1 of whom had germline DNA available. We focused on these 20 patients with paired germline and lymphoma TNFAIP3 sequence data. Importantly, these 20 patients were comparable to the entire cohort of pSS patients with lymphoma in terms of the main clinical characteristics (supplemental Table 2). All TNFAIP3 variants found in lymphoma tissue and not in germline DNA by the Sanger method were confirmed by pyrosequencing.

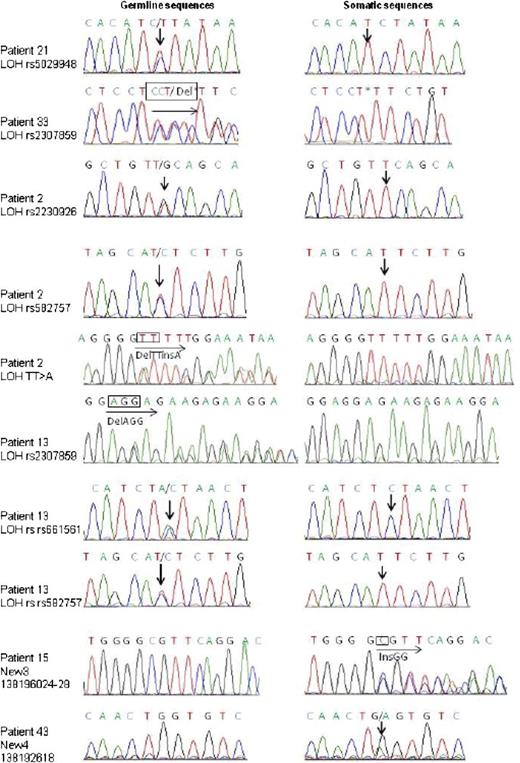

Among these 20 patients, 8 had no coding germline or lymphoma variation. Six patients had coding germline abnormalities with no further change in lymphoma sequence (1 patient had both rs2230926 and New 2, 1 patient had rs2230926 and the TT>A dinucleotide polymorphism, 3 patients had only rs2230926, and 1 patient had the 24-bp deletion in exon 1, New 1). Six other patients had potentially functional TNFAIP3 lymphoma abnormalities (Table 4). One patient had an insertion of 2 nucleotides (InsGG) in exon 3 leading to a stop codon (New 3). Another patient had a guanine-to-adenine mutation in exon 2 (New 4), leading to a stop codon in position 85 (Figure 1). We found loss of heterozygosity corresponding to hemizygous deletion in 3 patients, 1 of whom had 3 different losses of heterozygosity, suggesting that a large deletion occurred in TNFAIP3 in tumor DNA. Last, an additional patient had an extensive lymphoma deletion associated with a germline coding abnormality (rs2230926G) (Patient 2, Table 5). Sanger sequences of lymphoma variants not found in germline DNA are presented in Figure 2. To summarize, 12 (60%) of 20 patients in whom both germline and lymphoma DNA were available had a potentially functional abnormality of A20, either inherited or acquired. Germline abnormalities included an amino acid substitution in the case of the rs2230926G variant and/or the potential suppression of a Sp1 binding site in the case of the 24-bp deletion. Lymphoma abnormalities consisted of 2 mutations leading to a stop codon and 4 deletions leading to a truncated protein.

Sanger sequencing identification of TNFAIP3 somatic mutations or deletions in pSS patients with lymphoma. Sanger sequencing results for each TNFAIP3-mutated somatic sample are shown. Arrows indicate site of nucleotide change. Traces shown are representative of at least 2 independent amplification and sequencing reactions.

Sanger sequencing identification of TNFAIP3 somatic mutations or deletions in pSS patients with lymphoma. Sanger sequencing results for each TNFAIP3-mutated somatic sample are shown. Arrows indicate site of nucleotide change. Traces shown are representative of at least 2 independent amplification and sequencing reactions.

Abnormalities of A20 according to lymphoma type

Among the 20 patients in whom both germline and lymphoma DNA were available, 65% had MALT lymphoma; among this subgroup, 77% had potentially functional abnormalities of A20 compared with 28.6% of patients with other types of lymphoma (P < .0001; Table 6).

Frequencies of germline or somatic A20 abnormalities in MALT versus other lymphoma subtypes

| . | A20 abnormalities N (%) . | No. A20 abnormalities N (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| MALT lymphoma | 10 (77) | 3 (23) |

| Other histologic types | 2 (29) | 5 (71) |

| . | A20 abnormalities N (%) . | No. A20 abnormalities N (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| MALT lymphoma | 10 (77) | 3 (23) |

| Other histologic types | 2 (29) | 5 (71) |

Functional consequences of A20 abnormalities

Measurement of TNFAIP3 mRNA level by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR.

We did not demonstrate an association between the presence of the rs2230926 polymorphism in exon 3 or the 24-bp deletion in exon 1 (New 1) and TNFAIP3 mRNA level (supplemental Figure 3).

Transfection experiments of rs2230926 and New 3.

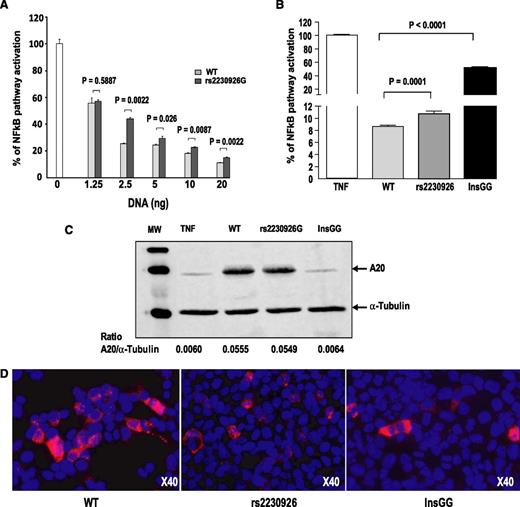

Transient transfection assays were performed to evaluate the functional consequences of A20 mutations on the NF-kB signaling pathway. The mutated A20 variants (rs2230926G and InsGG) were both less effective than the WT A20 in inhibiting NF-kB-dependent transactivation of the reporter gene in response to 10 ng/mL TNFα exposure (P < .0001) (Figure 3A-B). Western blot analysis confirmed that the rs2930926G protein variant was expressed at a similar level as the WT A20 protein (Figure 3C). As expected, no detectable InsGG variant (New 3) was observed in these conditions, as the anti-A20 antibody, used for western blot, recognizes an epitope located in the carboxy-terminal region of the protein (located in exon 7 between amino acid 500 and 530) that is lacking in the 122-amino acid truncated InsGG protein (New 3 variant). WT A20 and the 2 variants were equally expressed, as demonstrated by 2 types of techniques. First, qPCR demonstrated the same quantity of A20 DNA from the 3 types of plasmids, either directly from the plasmid or from the retrotranscription of A20 mRNA (supplemental Figure 4). Second, immunocytochemistry staining with an anti-FLAG-tagged antibody was able to detect the 3 types of A20 proteins, demonstrating the effectiveness of transfection (Figure 3D).

Functional consequences of TNFAIP3 mutations. (A) Dose-dependent inhibitory effect of wild-type (WT) and mutant A20 on TNFα-induced NF-kB activation. Increasing amounts of plasmids encoding either WT or mutant A20 (rs2230926G) were transfected into human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells, together with the NFκB-luciferase reporter and plasmid micro RNA β-galactosidase plasmids. The following day, cells were stimulated for 6 hours with 10 ng/mL TNFα. Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity, and ratios were expressed as percentage of NF-kB activation compared with that of the control without A20 plasmid, which was set at 100%. Results are means ± standard error of the mean of 6 determinations. (B) Inhibitory effect of WT and mutant A20 on TNFα-induced NF-kB activation. Transfection assays were performed as described earlier. Results are means ± standard error of the mean of several independent experiments performed with 6 to 35 determinations: 8 experiments for the WT A20 (n = 103 determinations), 7 experiments for the rs2230926G mutant (n = 101), and 3 experiments for the InsGG mutant (New 3; n = 44). (C) Western blot analysis of A20 protein variants. Total protein extracts were prepared from the same transfected-HEK 293T cells as described earlier, and western blot analysis of A20 protein variants demonstrated that the WT and the rs2230926 variant A20 proteins were expressed at the same level in our transfection assay. Of note, A20 monoclonal antibody, which recognizes an epitope located on exon 7, cannot detect the InsGG A20 protein variant that lacks the site of recognition of the antibody. However, the InsGG protein variant was expressed in transfected cells because it is able to partly inhibit NF-kB activation in response to TNF activation. (D) Immunodetection of A20 proteins in HEK 293T cells: HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with the expression vector encoding A20 (WT, rs2230926G, or InsGG). Sixteen hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with TNF (10 ng/mL) for 6 hours before fixation. Cells were immunolabeled with anti-FLAG (M2 produced in mouse; Sigma). Nuclei were 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole stained. ×40 magnification.

Functional consequences of TNFAIP3 mutations. (A) Dose-dependent inhibitory effect of wild-type (WT) and mutant A20 on TNFα-induced NF-kB activation. Increasing amounts of plasmids encoding either WT or mutant A20 (rs2230926G) were transfected into human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells, together with the NFκB-luciferase reporter and plasmid micro RNA β-galactosidase plasmids. The following day, cells were stimulated for 6 hours with 10 ng/mL TNFα. Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity, and ratios were expressed as percentage of NF-kB activation compared with that of the control without A20 plasmid, which was set at 100%. Results are means ± standard error of the mean of 6 determinations. (B) Inhibitory effect of WT and mutant A20 on TNFα-induced NF-kB activation. Transfection assays were performed as described earlier. Results are means ± standard error of the mean of several independent experiments performed with 6 to 35 determinations: 8 experiments for the WT A20 (n = 103 determinations), 7 experiments for the rs2230926G mutant (n = 101), and 3 experiments for the InsGG mutant (New 3; n = 44). (C) Western blot analysis of A20 protein variants. Total protein extracts were prepared from the same transfected-HEK 293T cells as described earlier, and western blot analysis of A20 protein variants demonstrated that the WT and the rs2230926 variant A20 proteins were expressed at the same level in our transfection assay. Of note, A20 monoclonal antibody, which recognizes an epitope located on exon 7, cannot detect the InsGG A20 protein variant that lacks the site of recognition of the antibody. However, the InsGG protein variant was expressed in transfected cells because it is able to partly inhibit NF-kB activation in response to TNF activation. (D) Immunodetection of A20 proteins in HEK 293T cells: HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with the expression vector encoding A20 (WT, rs2230926G, or InsGG). Sixteen hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with TNF (10 ng/mL) for 6 hours before fixation. Cells were immunolabeled with anti-FLAG (M2 produced in mouse; Sigma). Nuclei were 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole stained. ×40 magnification.

Discussion

Among this cohort of pSS patients with lymphoma, we demonstrated functional abnormalities of A20 in 60% of the patients: half of germinal origin and half of somatic (tumor) origin. Among patients with MALT lymphoma complicating pSS, this frequency increased to 77%.

Previous studies of TNFAIP3 in autoimmune diseases have demonstrated association of several variants with disease risk, including the rs2230926 coding SNP. Our findings indicate that, at least in the context of pSS, functional variants of TNFAIP3 are associated primarily with autoimmune disease complicated by the development of lymphoma. Hypomorphic variants of A20 may promote more active disease, which is more likely to be complicated by lymphoid malignancies. In pSS, A20 is likely to be essential for controlling NF-kB activation and ensuring B lymphocytes avoid lymphomatous escape resulting from continuous stimulation as a result of the autoimmune process. Our observation that 30% of the patients with pSS and lymphoma had functional abnormalities of A20 (mutations, deletions, or insertions) in the lymphomatous tissue also supports this model. By performing transfection of either WT or mutant TNFAIP3 sequences, we confirmed that 2 of these abnormalities are hypomorphic. The coding rs2230926G and InsGG polymorphisms resulted in less-effective inhibition of TNF-induced NF-kB activity. Our findings for rs2230926G confirm a previous study employing similar methods that also demonstrated impaired control of NF-kB activation.5

Although this study is unique in the examination of both germline and tumoral genetic abnormalities among pSS patients who developed lymphoma, there are a number of limitations. Most important was the lack of available lymphoma DNA from roughly a third of the tumor samples as a result of degradation. It is also difficult to determine whether the association of TNFAIP3 variants with pSS complicated by lymphoma relates primarily to the lymphoma or to the underlying autoimmune disease process. However, the prevalence of A20 abnormalities in pSS patients with MALT lymphoma in our study (77%) is higher than what has been generally described in MALT lymphoma (prevalence, 22%-28%).6,7 This suggests specific involvement of A20 inactivation in lymphoma complicating autoimmune disease.

Recent studies have implicated other genes that control NF-kB activation in other types of lymphoma, such as MYD88 in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia19 and Notch2 in marginal zone lymphoma.20,21 The scenario may be somewhat different in the setting of lymphoma complicating autoimmune diseases, where genetic abnormalities could be either germline or somatic in origin. The high incidence of germline abnormalities was rather unexpected.

Germline abnormalities of A20 might promote slightly impaired control of NF-kB activation in all cells. This slightly increased NF-kB activity could contribute, along with many other factors, to propagating inflammation, favoring autoimmunity and activation of autoimmune B cells. Such autoreactive B cells with ongoing stimulation by autoantigens are prone to proliferate in a clonal manner. Complete control of NF-kB activation is probably necessary to avoid such B-cell clonal proliferation, which may explain why slight abnormalities of A20 of germline origin may have consequences primarily in B cells. Interestingly, it has been recently demonstrated that germline gain of function mutations of CARD11, involved in NF-kB activation in both B and T cells, could induce lymphoproliferation restricted to B cells.22

Alternatively, the genetic events allowing clonal B cells to escape may occur within the B cells themselves. Autoimmune B cells subjected to perpetual stimulation are more sensitive to the presence of additional mutations leading to clonal selection. Such acquired abnormalities of TNFAIP3 have been described in association with MALT lymphoma, and previous work has also demonstrated that the survival of MALT lymphoma depends critically on constitutive NF-kB activity.10

Our results are also consistent with a “two-hit” process, in which a combination of germline and somatic abnormalities of TNFAIP3 promote the development of lymphoma, as illustrated by one of our patients who had a germline coding abnormality (rs2230926G) and an extensive lymphoma deletion. Of interest, uncontrolled activation of NF-kB has been shown to promote the survival of germline B cells, which could lead to an increased number of somatic mutations, including oncogenic mutations.4 It will be of interest to determine whether other genes that act to control NF-kB activation contribute to the development of autoimmunity-associated lymphoma.

This study demonstrates that A20 inactivation, and thus NF-kB overactivation, plays a key role in lymphomagenesis in the context of autoimmunity. It supports a scenario in which the presence of germinal and/or somatic abnormalities of genes, leading to impaired control of NF-kB activation in B cells continuously stimulated by autoimmunity, enhances the risk for lymphoma, a concept that is both novel and paradigm-shifting in the area of lymphomagenesis and autoimmunity. These data provide a rationale for targeting NF-kB in B-cell lymphoma complicating pSS and perhaps also as a preventive intervention strategy in pSS patients with active disease.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr J. Benessiano and all staff members of the Bichat Hospital Biological Resource Center (Paris, France) for their help in centralizing and managing biologic data collection from the French Atteinte Systémique et Evolution des patients atteints de Syndrome de Sjögren primitive (ASSESS) cohort, a prospective cohort of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, and D. Batouche (Unité de Recherche Clinique Paris Sud, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France) for clinical data collection. The authors thank the following investigators of the ASSESS cohort (all in France), who recruited the patients and conducted follow-up: A. L. Fauchais (Limoges), S. Rist (Orleans), D. Sené (Paris), V. Le Guern (Paris), G. Hayem (Paris), J. Sibilia (Strasbourg), J. Morel (Montpellier), A. Saraux (Brest), A. Perdriger (Rennes), X. Puechal (Le Mans), and V. Goeb (Rouen). The authors thank the following clinicians who recruited the patients apart from the ASSESS cohort: A. Le Quellec, B. Bienvenu and C. Roux. The authors thank the following pathologists who helped us in collecting tumor samples: MC. Copin (Lille), L. Gibault (Paris), V. Meignin (Paris), I. Quintin-Roue (Brest), N. Moukarbel and W. Essamet (Clermont Ferrand), P. Fouret (Paris), C. Le Corre (Brest), M. Raphael (Le Kremlin Bicêtre), A. Heurseau (Bobigny), P. Bruneval (Paris), A. Le Tourneau (Paris), A. Francois (Rouen), F. Franck (Clermont Ferrand), C. Spiekermann (Nevers), M Wassef (Paris), A. de Mascarel (Bordeaux), M. Svreck (Paris), D. Canioni (Paris), L. Martin (Bobigny), D. Chatelain (Amiens), J. Bosq (Villejuif), B. Leger-Ravet (Longjumeau) and G. Escourrou (Toulouse).

This work was supported by grants from the French ministry of health (PHRC 2006-AOM06133), French ministry of research (ANR- 2010-BLAN-1133 01), and the National Institutes of Health (P50 AR0608040 and 5U19 AI082714 [to K.L.S. and C.J.L]).

Authorship

Contribution: X.M. and C.M.-R. supervised the project; G.N., S.B., and S.V. performed experiments; T.L. reevaluated all lymphoma tumor material; J.N., K.E.T., and L.A.C. performed the genetic analyses; G.N., A.M., C.M.-R., M.L., L.A.C., and X.M. participated in writing the manuscript; J.M. provided help with exon sequencing; C.J.L. and K.L.S. participated in generation of PC data; J.-J.D., E.H., and J.E.G. participated in patient recruitment; M.L. supervised the transfection experiments; and F.B. and J.T. performed the pyro-sequencing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Prof Xavier Mariette, Service de Rhumatologie, Hôpital Bicêtre, 78 rue du Général Leclerc, 94275 Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France; e-mail: xavier.mariette@bct.aphp.fr.

References

Author notes

G.N., S.B., and C.M.-R. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal