Key Points

Novel FLI1 and RUNX1 alterations were identified in 6 of 13 patients with excessive bleeding and platelet granule secretion defects.

Two FLI1 alterations predicting amino acid substitutions in the DNA-binding domain of FLI1 abolished transcriptional activity of FLI1.

Abstract

We analyzed candidate platelet function disorder genes in 13 index cases with a history of excessive bleeding in association with a significant reduction in dense granule secretion and impaired aggregation to a panel of platelet agonists. Five of the index cases also had mild thrombocytopenia. Heterozygous alterations in FLI1 and RUNX1, encoding Friend leukemia integration 1 and RUNT-related transcription factor 1, respectively, which have a fundamental role in megakaryocytopoeisis, were identified in 6 patients, 4 of whom had mild thrombocytopenia. Two FLI1 alterations predicting p.Arg337Trp and p.Tyr343Cys substitutions in the FLI1 DNA-binding domain abolished transcriptional activity of FLI1. A 4-bp deletion in FLI1, and 2 splicing alterations and a nonsense variation in RUNX1, which were predicted to cause haploinsufficiency of either FLI1 or RUNX1, were also identified. Our findings suggest that alterations in FLI1 and RUNX1 may be common in patients with platelet dense granule secretion defects and mild thrombocytopenia.

Introduction

Inherited platelet function disorders (PFDs), which cause excessive bleeding, are heterogeneous and can seldom be linked to a causative gene using clinical and laboratory phenotype alone.1 The advent of techniques allowing selective capture and enrichment of target gene sequences, coupled with next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, has facilitated the rapid identification of disease-associated variants by enabling the simultaneous analysis of large numbers of genes. We have used NGS to investigate index cases from 13 unrelated families recruited to the UK Genotyping and Phenotyping of Platelets (UK GAPP) study2 with significantly reduced platelet dense granule secretion using lumi-aggregometry.

Study design

Recruitment of patients and platelet phenotyping

Index cases and affected relatives from a subgroup of 13 families, recruited to the UK GAPP study on the basis of excessive clinical bleeding and a suspicion of an inherited platelet disorder, were investigated. These individuals were diagnosed with a platelet dense granule secretion defect following platelet phenotyping but had no other features of Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for recruitment to the study, and the criteria for diagnosis of a dense granule secretion defect, have been described.3 Platelet aggregation and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) secretion were assessed in platelet-rich plasma using a rationalized panel of platelet agonists and a dual-channel Chronolog lumi-aggregometer.3 This study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee West Midlands–Edgbaston (REC reference: 06/MRE07/36) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Analysis of candidate genes

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood, and NGS of candidate PFD genes was undertaken on an ABI-SOLiD3+ or an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx platform.2,4 Novel sequence variations identified by NGS were confirmed by conventional Sanger sequencing. Where possible, patients were selected for NGS analysis on the basis of having an affected relative who was also available for study.

Detection of MYH10 in platelets

Nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIB (MYH10) was detected in platelets by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting as described.5

Results and discussion

To date, 366 patients, from 292 unrelated families, have been recruited to the UK GAPP study, of whom 56 (15%) have been classified as having a secretion defect. NGS analysis of candidate PFD genes was undertaken in 13 of the patients with defects in secretion, who were selected, where possible, on the basis of having an affected relative who was also available for study. Novel heterozygous alterations in either the FLI1 or RUNX1 gene were identified in 6 of the families (F1 to F6) (Table 1). Two nonsynonymous FLI1 alterations, c.1009C>T and c.1028A>G, predicting p.R337W and p.Y343C substitutions in the highly conserved DNA-binding domain of FLI1, were identified in affected members of F1 and F2, and a 4-bp frameshift deletion in FLI1 (c.992-995del; p.Asn331Thrfs*4) was present in both affected members of F3. Three RUNX1 variations predicted to cause RUNX1 haploinsufficiency were identified; donor splice site transversions, c.508+1G>T and c.351+1G>T, were detected in F4 and F5, respectively, and a nonsense mutation in codon 106 (c.317G>A; p.Trp106Stop) was detected in the index case from F6.

Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of subjects with platelet dense granule secretion defects

| Family (F)/patient identification* . | FLI1 or RUNX1 alteration† . | Effect . | Platelet count (× 109/L)‡ . | Mean platelet volume (fL) . | ATP secretion (nmol/1 × 108 platelets)§ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1; II.1 | FLI1; c.1009 C>T | p.Arg337Trp | 244 | 10.3 | 0.37 |

| F1; III.1 | FLI1; c.1009 C>T | p.Arg337Trp | 180 | 10.5 | 0.07 |

| F2; II.5 | FLI1; c.1028 A>G | p.Tyr343Cys | 92 | 8.8 | ND|| |

| F2; III.1 | FLI1; c.1028 A>G | p.Tyr343Cys | 117 | 8.6 | ND|| |

| F3.1 | FLI1; c.992-995del | p.Asn331Thrfs*4 | 142 | 11.4 | 0.38 |

| F3.2 | FLI1; c.992-995del | p.Asn331Thrfs*4 | 157 | 11.8 | 0.57 |

| F4.1 | RUNX1; c.508+1 G>T | Splicing | 302 | 7.3 | 0.32 |

| F4.2 | RUNX1; c.508+1 G>T | Splicing | 70 | 7.5 | ND |

| F4.3 | RUNX1; c.508+1 G>T | Splicing | 130 | 7.1 | 0.62 |

| F5 | RUNX1; c.351+1G>T | Splicing | 139 | 8.0 | 0.35 |

| F6.1 | RUNX1; c.317 G>A | p.Trp106Stop | 100 | 8.0 | 0.25 |

| F7 | – | – | 233 | 8.5 | 0.57 |

| F8 | – | – | 190 | 8.5 | ND |

| F9 | – | – | 205 | 8.4 | 0.48 |

| F10 | – | – | 370 | 8.6 | 0.31 |

| F11 | – | – | 225 | NA | 0.63 |

| F12 | – | – | 245 | NA | 0.52 |

| F13 | – | – | 114 | 10.9 | 0.12 |

| Family (F)/patient identification* . | FLI1 or RUNX1 alteration† . | Effect . | Platelet count (× 109/L)‡ . | Mean platelet volume (fL) . | ATP secretion (nmol/1 × 108 platelets)§ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1; II.1 | FLI1; c.1009 C>T | p.Arg337Trp | 244 | 10.3 | 0.37 |

| F1; III.1 | FLI1; c.1009 C>T | p.Arg337Trp | 180 | 10.5 | 0.07 |

| F2; II.5 | FLI1; c.1028 A>G | p.Tyr343Cys | 92 | 8.8 | ND|| |

| F2; III.1 | FLI1; c.1028 A>G | p.Tyr343Cys | 117 | 8.6 | ND|| |

| F3.1 | FLI1; c.992-995del | p.Asn331Thrfs*4 | 142 | 11.4 | 0.38 |

| F3.2 | FLI1; c.992-995del | p.Asn331Thrfs*4 | 157 | 11.8 | 0.57 |

| F4.1 | RUNX1; c.508+1 G>T | Splicing | 302 | 7.3 | 0.32 |

| F4.2 | RUNX1; c.508+1 G>T | Splicing | 70 | 7.5 | ND |

| F4.3 | RUNX1; c.508+1 G>T | Splicing | 130 | 7.1 | 0.62 |

| F5 | RUNX1; c.351+1G>T | Splicing | 139 | 8.0 | 0.35 |

| F6.1 | RUNX1; c.317 G>A | p.Trp106Stop | 100 | 8.0 | 0.25 |

| F7 | – | – | 233 | 8.5 | 0.57 |

| F8 | – | – | 190 | 8.5 | ND |

| F9 | – | – | 205 | 8.4 | 0.48 |

| F10 | – | – | 370 | 8.6 | 0.31 |

| F11 | – | – | 225 | NA | 0.63 |

| F12 | – | – | 245 | NA | 0.52 |

| F13 | – | – | 114 | 10.9 | 0.12 |

Heterozygous nucleotide changes present in FLI1 and RUNX1 and their predicted effects on the resulting RNA or protein are shown.

NA, not available; ND, not detectable.

Index cases are indicated in bold font.

Alterations are numbered according to positions in the NM_002017.3 and NM_001754 transcripts for FLI1 and RUNX1, respectively.

Mean platelet counts are shown, the normal reference range is 150 × 109 to 400 × 109 platelets per L, and thrombocytopenia is defined as platelet count <150 × 109 platelets per L.

ATP secreted in response to 100 μM of PAR-1 receptor–specific peptide SFLLRN; fifth percentile in healthy volunteers is 0.82 nmol/1 × 108 platelets.

ATP secretion was measured in response to 1 U/mL of thrombin in the center where these subjects were recruited, against a normal reference range of 0.73 to 1.80 nmol/1 × 108 platelets.

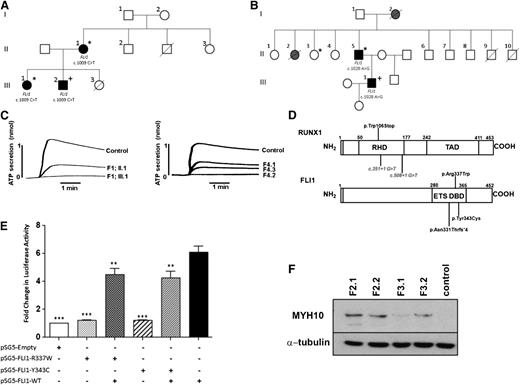

The presence of an FLI1 or RUNX1 alteration was associated with symptoms of excessive bleeding in all index cases, and the patients’ affected family members, and with mild thrombocytopenia in 5 of the families (Table 1; supplemental Figure 1, see the Blood Web site). In F4, the splice site alteration in RUNX1 was associated with a normal platelet count in the index case, but with thrombocytopenia in 2 affected relatives. The missense variations in FLI1 were also associated with alopecia, eczema or psoriasis, and recurrent viral infections in affected individuals in F1, and with mild thrombocytopenia, alopecia, and eczema in the affected individuals in F2 (Figure 1A-B).

Excessive bleeding and platelet dense granule secretion defects are associated with heterozygous mutations in FLI1 and RUNX1. (A-B) Pedigrees showing inheritance of mild bleeding, alopecia totalis, and other clinical features in families 1 (A) and 2 (B). Individuals heterozygous for the c.1009C>T and c.1028A>G transitions in FLI1 are indicated. Lines through symbols indicate deceased individuals. In panel A, individuals with bleeding symptoms, alopecia, and confirmed platelet dense granule secretion defects are indicated by black filled symbols. An asterisk indicates the presence of eczema and a history of recurrent viral infections. The presence of psoriasis is indicated by a “+” sign. In panel B, individuals with bleeding symptoms and alopecia are indicated by black or gray filled symbols. Black filled symbols indicate individuals with confirmed platelet dense granule secretion defect and mild thrombocytopenia. An asterisk indicates a history of infective endocarditis, and the presence of eczema and colitis is indicated by a “+” sign. (C) ATP secretion in response to 100 μM PAR1 peptide in 2 members of F1 with the c.1009C>T transition in FLI1 and 3 members of F4 with the c.508+1G>T transversion in RUNX1 alongside controls. (D) Schematic diagram of RUNX1 and FLI1 showing the regions of the proteins affected by mutations identified in this study. Intronic mutations, predicted to interfere with splicing of the RUNX1 RNA, are shown in italics. (E) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with wild-type (WT) and variant FLI1 constructs, or combinations thereof, and pGL3.10-GP6-luciferase and pRLnull-Renilla reporters as shown, and firefly and Renilla luciferase expression assessed in cell lysates 48 hours later. Data represent the means (± standard error of the mean) of 3 independent experiments; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (F) MYH10 protein expression in platelets from patients with FLI1 mutations (F2.1 and F2.2 with p.Tyr343Cys FLI1 mutation; F3.1 and F3.2 with p.Asn331Thrfs*4 FLI1 mutation) and a healthy control.

Excessive bleeding and platelet dense granule secretion defects are associated with heterozygous mutations in FLI1 and RUNX1. (A-B) Pedigrees showing inheritance of mild bleeding, alopecia totalis, and other clinical features in families 1 (A) and 2 (B). Individuals heterozygous for the c.1009C>T and c.1028A>G transitions in FLI1 are indicated. Lines through symbols indicate deceased individuals. In panel A, individuals with bleeding symptoms, alopecia, and confirmed platelet dense granule secretion defects are indicated by black filled symbols. An asterisk indicates the presence of eczema and a history of recurrent viral infections. The presence of psoriasis is indicated by a “+” sign. In panel B, individuals with bleeding symptoms and alopecia are indicated by black or gray filled symbols. Black filled symbols indicate individuals with confirmed platelet dense granule secretion defect and mild thrombocytopenia. An asterisk indicates a history of infective endocarditis, and the presence of eczema and colitis is indicated by a “+” sign. (C) ATP secretion in response to 100 μM PAR1 peptide in 2 members of F1 with the c.1009C>T transition in FLI1 and 3 members of F4 with the c.508+1G>T transversion in RUNX1 alongside controls. (D) Schematic diagram of RUNX1 and FLI1 showing the regions of the proteins affected by mutations identified in this study. Intronic mutations, predicted to interfere with splicing of the RUNX1 RNA, are shown in italics. (E) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with wild-type (WT) and variant FLI1 constructs, or combinations thereof, and pGL3.10-GP6-luciferase and pRLnull-Renilla reporters as shown, and firefly and Renilla luciferase expression assessed in cell lysates 48 hours later. Data represent the means (± standard error of the mean) of 3 independent experiments; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (F) MYH10 protein expression in platelets from patients with FLI1 mutations (F2.1 and F2.2 with p.Tyr343Cys FLI1 mutation; F3.1 and F3.2 with p.Asn331Thrfs*4 FLI1 mutation) and a healthy control.

Examination of platelet secretion and aggregation in all subjects carrying FLI1 or RUNX1 defects consistently revealed the predominant platelet abnormality to be a significant reduction in platelet ATP secretion in response to all agonists tested (Figure 1C, Table 1, supplemental Figure 2, and data not shown). As reported previously for patients with dense granule secretion defects, reductions in platelet aggregation in response to collagen and PAR-1 were observed in some, but not all, subjects and were usually more apparent at low or intermediate agonist concentrations (data not shown).3

FLI1 is a member of the ETS (E–twenty six) family of transcription factors, which is expressed primarily in hematopoietic cells and regulates genes expressed both early and late in megakaryocytopoiesis, including GP6.6-10 Patients with Paris-Trousseau syndrome (PTS), who are hemizygous for FLI1 as a result of a deletion of chromosome 11q23, have an increased tendency to bleed, which is associated with thrombocytopenia, and enlarged platelets displaying giant α-granules.10-12 It is thought that transient monoallelic expression of FLI1 at an early stage during megakaryocytopoiesis, coupled with hemizygous loss of FLI1 in patients with PTS, which results in a complete lack of FLI1 expression, accounts for the generation of 2 distinct subpopulations of normal and immature megakaryocytes in patients with PTS.10 The identification of alterations predicting substitutions in the DNA-binding domain of FLI1 and their association with symptoms in 2 families suggests a role for FLI1 in the pathogenesis of bleeding in these families.

We investigated whether the p.R337W and p.Y343C substitutions could alter the DNA-binding capacity of FLI1 by examining the ability of the recombinant FLI1 variants to bind to an ETS site in the GP6 promoter using the dual-luciferase reporter assay to measure GP6 promoter activity. There was a complete loss in the ability of the R337W and Y343C FLI1 variants to induce GP6 promoter activity compared with that of WT-FLI1 (P < .001; Figure 1E). Furthermore, coexpression of either the R337W or the Y343C variant with WT-FLI1, to mimic heterozygosity, resulted in significant reductions in the transcriptional activity to ∼60% of that of WT-FLI1 alone (P < .01), indicating that these mutations disrupt DNA binding of FLI1 and will cause a reduction in activation of megakaryocyte-specific genes (Figure 1E). Of interest is a previous study, which showed that R337 is critical for the function of nuclear localization signal 2 of FLI1 and that an R337A substitution caused a reduction in nuclear accumulation of FLI1.13 However, as with the R337W variant, the R337A substitution was shown to disrupt the DNA-binding ability of FLI1 and, consequently, to downregulate expression of FLI1-inducible megakaryocyte-specific genes.13

As a member of the RUNT family of transcription factors, the role of RUNX1 in regulating megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation is well established. RUNX1 has been shown to cooperate with FLI1 in the late stages of megakaryopoiesis.14,15 Inherited RUNX1 mutations are recognized to lead to autosomal dominant thrombocytopenia and impaired platelet function and are associated with a propensity to myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia.1 RUNX1-mediated silencing of the MYH10 gene is required for the switch from mitosis to endomitosis during megakaryocyte maturation. The persistence of MYH10 in platelets was recently proposed as a biomarker for RUNX1 alterations in patients with familial thrombocytopenia and for FLI1 deletions in PTS.5,16 The detection of MYH10 in platelets from patients carrying the p.Tyr343Cys and the p.Asn331Thrfs*4 FLI1 variations confirms the use of MYH10 detection as a biomarker for FLI1 alterations (Figure 1F). Indeed, immunoblot detection of MYH10 expression in platelets would be a useful initial screening test for inherited platelet disorders caused by abnormalities in RUNX1 or FLI1. Dosage of RUNX1 is thought to contribute to the risk of AML because missense mutations that result in variants that can heterodimerize with normal RUNX1 and act in a dominant-negative manner to compete with the normal protein have been reported to be associated with a higher risk of hematologic malignancy than mutations resulting in haploinsufficiency.17 The absence of hematologic malignancies to date in the 3 families with RUNX1 mutations identified in this study, which were all predicted to result in haploinsufficiency, would support this observation.

The identification of RUNX1 or FLI1 alterations in 6 of 13 unrelated index cases with dense granule secretion disorder, 4 of whom had thrombocytopenia, suggests that defects in these genes will account for a significant proportion of patients with defects in platelet granule secretion and excessive bleeding.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Centre for Genome Research, University of Liverpool, for enrichment of genomic DNA and NGS on the ABI-SOLiD3+ platform and Professor M. Trojanowska, Boston University, for providing the WT-FLI1 expression construct.

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (RG/09/007/27917) and the Wellcome Trust (093994). S.P.W. holds a British Heart Foundation Chair. The GAPP project is included in the UK National Institute for Health Research Non Malignant Haematology Specialty Group Portfolio (ID 9858) and receives support in patient recruitment from this group and from Comprehensive Local Research Networks, with Birmingham and the Black Country acting as the lead Comprehensive Local Research Network. The authors acknowledge the support of all collaborating clinicians and staff in participating UK hemophilia centers.

Authorship

Contribution: J.S. and M.E.D. wrote the paper; J.S., N.V.M., D.B., G.C.L., M.L., B.D., M.A.S., K.M., K.H., and V.C.L. contributed to the data collection and laboratory analyses; G.C.L., M.L., K.T., J.M., J.T.W., P.W.C., and M.M. recruited patients and contributed clinical data to the study; M.E.D. and S.P.W. coordinated the study; and all authors read and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Martina Daly, Department of Cardiovascular Science, University of Sheffield Medical School, Beech Hill Rd, Sheffield, S10 2RX, United Kingdom; e-mail: m.daly@sheffield.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

J.S. and N.V.M. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal