Key Points

The best survival benefit of HSCT is observed in patients with FA who are transplanted before 10 years with bone marrow after a fludarabine-based regimen.

Long-term outcome of patients with FA after transplantation is mainly affected by secondary malignancies and chronic graft-versus-host disease.

Abstract

Although allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains the only curative treatment for patients with Fanconi anemia (FA), published series mostly refer to single-center experience with limited numbers of patients. We analyzed results in 795 patients with FA who underwent first HSCT between May 1972 and January 2010. With a 6-year median follow-up, overall survival was 49% at 20 years (95% confidence interval, 38-65 years). Better outcome was observed for patients transplanted before the age of 10 years, before clonal evolution (ie, myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia), from a matched family donor, after a conditioning regimen without irradiation, the latter including fludarabine. Chronic graft-versus-host disease and secondary malignancy were deleterious when considered as time-dependent covariates. Age more than 10 years at time of HSCT, clonal evolution as an indication for transplantation, peripheral blood as source of stem cells, and chronic graft-versus-host disease were found to be independently associated with the risk for secondary malignancy. Changes in transplant protocols have significantly improved the outcome of patients with FA, who should be transplanted at a young age, with bone marrow as the source of stem cells.

Introduction

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a rare, phenotypically heterogeneous, inherited disorder clinically characterized by congenital abnormalities, progressive bone marrow failure (BMF), and a predisposition to develop malignancies, especially acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and squamous cell carcinoma.1-5 Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) still represents the only curative option for BMF,6-9 although it does not prevent the occurrence of solid tumors, mostly in the head and neck.10

Conditioning regimens based on reduced doses of cyclophosphamide, either alone or with limited field radiotherapy, have cured BMF in a large proportion of patients transplanted from an HLA-identical sibling.6,11,12 Results of unrelated donor HSCT have been less encouraging, however, mainly because of increased engraftment failure and higher incidences of both acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GvHD),7,13 although better results have recently been reported.8,9,14 The use of fludarabine-based reduced-intensity conditioning regimens with or without T-cell depletion8,9,14-17 seems to contribute to this improvement, as well as better supportive care18 and probably better HLA typing, as shown in other nonmalignant diseases.19,20

However, some questions remain unanswered in this particularly difficult and rare clinical situation: What is the best source of stem cells to transplant a nonmalignant disease in which the risk for graft failure is high? What are the factors affecting the long-term outcome post-HSCT? It has been difficult to answer these questions until now, as only a few registry reports on more than 50 patients with FA have been published.6-9 To address these issues, we performed an analysis on the largest cohort of patients with FA post-HSCT studied to date.

Patients, materials, and methods

Data collection

This retrospective multicenter study was conducted through the Severe Aplastic Anemia and the Pediatric Working Parties of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). The EBMT maintains a registry in which participating centers report consecutively transplanted patients. Data management is performed by each center independently. An additional questionnaire was sent to all centers with patients with FA requiring more specific details regarding FA: clinical characteristics at time of transplant (growth retardation, skin hypopigmentation, and somatic malformations), indication for stem cell transplantation, and long-term follow-up. All data were carefully checked, and institutions’ physicians were contacted (by R.P.L. and/or R.P.) if there were any inconsistencies. Some of the patients have already been previously reported.7,10,21,22 All patients or legal guardians provided informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the local institutional review boards of the participant centers.

Inclusion criteria

All consecutive patients with FA who underwent first allogeneic stem cell transplantation from an HLA-matched related or unrelated donor and who have been reported to EBMT were included. Sibling and unrelated donors and recipients were matched if HLA A and B were identical at the generic level and HLA DRB1 was identical at the allelic level. Patients were included if an increase was observed in lymphocyte chromosome breaks after exposure to DNA cross-linking agents. Patients who received cord blood or haploidentical transplants were not included in the study; neither were patients who received 1 or more antigen-mismatched related donors.

End points

Myelodysplastic syndrome and AML were defined according to classical definition.23,24 Engraftment was defined as achieving an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5 × 109/L for at least 3 consecutive days. Acute GvHD and chronic GvHD were defined and graded according to previous published criteria.25,26 For acute GvHD, time to GvHD was randomly selected, using random sampling with replacement in empirical distribution in cases in which dates were missing. Nonrelapse mortality (NRM) was defined as any cause of death other than return of marrow to its status before transplant. Survival was calculated from the date of transplantation to the date of last follow-up or date of death from any cause.

Statistical methods

Analysis was carried out at the reference date of January 4, 2011. Data are presented as numbers (and percentages). Death was considered a competing risk in the analyses of acute and chronic GvHD. For competing risk analyses, cumulative incidence functions (CIF) were estimated.27 Factors associated with outcomes were analyzed using Fisher's exact tests and logistic regression models (engraftment), Gray's tests and the Fine-Gray regression model28,29 (acute GvHD), a proportional hazards models for the cause-specific hazard30 (chronic GvHD and NRM), and Cox proportional hazards models (overall survival [OS]). The proportional hazards assumption was checked by the examination of Schoenfeld residuals and Grambsch and Therneau’s lack-of-fit test.31 In the case of nonproportional hazards, models with time-varying effects were also fitted. Interaction between donor and other variables were tested. When the number of events was sufficient, all considered potential predictors were entered in the models. Otherwise, a stepwise variable selection procedure was used to limit the models to at least 5 events per variable, as this has been shown to have similar properties to the usual rule of 10 events per variable for survival models.32 In case of missing data, multiple imputations were used, which allowed for creating several data sets where missing data were predicted (detailed in the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site.).33,34 All tests were 2-sided, and P ≤ .05 was considered to indicate significant association. Analyses were performed using the R statistical software version 2.15.0.

Results

Study cohort

From 1972 to 2009, data from 795 consecutive patients with FA who underwent their first allogeneic HSCT from an HLA-matched donor were reported to the EBMT by 150 centers (HLA-identical sibling, n = 471; HLA-matched unrelated donor, n = 324). Of the transplantations, 90% were performed after 1990 and 49% were performed after 1999 (n = 390). The median follow-up time of the study group was 6 years (range, 0 months-28 years). Patient, disease, and transplantation characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of patients, disease, and transplantation procedures

| Variable . | Transplant year . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972-1999 . | 2000-2009 . | |||

| HLA-identical siblings . | HLA-matched unrelated donors . | HLA-identical siblings . | HLA-matched unrelated donors . | |

| Number of patients (% by period) | 260 (64) | 145 (36) | 211 (54) | 179 (46) |

| Age at diagnosis, no. (%) | ||||

| 0-5 y | 85 (33) | 54 (37) | 54 (26) | 64 (36) |

| 5-10 y | 106 (41) | 68 (47) | 97 (46) | 82 (46) |

| 10-20 y | 61 (23) | 20 (14) | 43 (20) | 27 (15) |

| >20 y | 8 (3) | 3 (2) | 17 (8) | 6 (3) |

| Age at transplant, no. (%) | ||||

| 0-10 y | 117 (45) | 70 (48) | 115 (55) | 100 (56) |

| 10-20 y | 126 (48) | 68 (47) | 73 (35) | 62 (35) |

| >20 y | 17 (7) | 7 (5) | 23 (11) | 17 (9) |

| Sex, no. (%) | ||||

| Female | 116 (45) | 72 (50) | 97 (46) | 90 (50) |

| Male | 143 (55) | 73 (50) | 112 (53) | 89 (50) |

| Unknown | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Donor/recipient sex, no. (%) | ||||

| Female/female | 63 (24) | 40 (28) | 53 (25) | 36 (20) |

| Female/male | 56 (22) | 31 (21) | 62 (29) | 22 (12) |

| Male/female | 51 (20) | 30 (21) | 43 (20) | 48 (27) |

| Male/male | 84 (32) | 39 (27) | 48 (23) | 66 (37) |

| Unknown | 6 (2) | 5 (3) | 5 (2) | 7 (4) |

| Donor/recipient CMV status, no. (%) | ||||

| Negative/negative | 47 (18) | 30 (21) | 19 (9) | 37 (21) |

| Negative/positive | 16 (6) | 19 (13) | 12 (6) | 33 (18) |

| Positive/negative | 15 (6) | 18 (12) | 10 (5) | 11 (6) |

| Positive/positive | 40 (15) | 22 (15) | 86 (41) | 32 (18) |

| Unknown | 142 (55) | 56 (39) | 84 (40) | 66 (37) |

| Bone marrow status before stem cell transplantation, no. (%) | ||||

| AA | 249 (96) | 133 (92) | 193 (91) | 162 (91) |

| MDS/AML | 11 (4) | 12 (8) | 18 (9) | 17 (9) |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, no. (%) | ||||

| ≤12 mo | 68 (26) | 22 (15) | 89 (42) | 47 (26) |

| >12 mo | 192 (74) | 123 (85) | 122 (58) | 132 (74) |

| Stem cell source, no. (%) | ||||

| BM | 242 (93) | 132 (91) | 140 (66) | 111 (62) |

| PB | 18 (7) | 13 (9) | 71 (34) | 67 (38) |

| Conditioning | ||||

| Missing conditioning, no. (%) | 30 (12) | 13 (9) | 9 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Fludarabine, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 215 (99) | 128 (98) | 90 (45) | 59 (34) |

| Yes | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 112 (55) | 115 (66) |

| Anti-T serotherapy, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 159 (64) | 43 (30) | 91 (45) | 63 (36) |

| Yes | 59 (24) | 88 (62) | 111 (55) | 111 (64) |

| Unknown | 30 (12) | 12 (8) | — | — |

| Irradiation, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 33 (13) | 11 (8) | 126 (62) | 100 (57) |

| TLI/TAI | 65 (26) | 31 (22) | 1 (<1) | 9 (5) |

| TBI* | 89 (36) | 80 (56) | 11 (5) | 21 (12) |

| No TBI, TLI/TAI unknown | 44 (18) | 14 (10) | 61 (30) | 38 (22) |

| Unknown | 17 (7) | 7 (5) | 3 (1) | 6 (3) |

| Ex-vivo T-cell manipulation, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 132 (53) | 55 (38) | 184 (91) | 142 (82) |

| Yes | 13 (5) | 47 (33) | 11 (5) | 23 (13) |

| Unknown | 103 (42) | 41 (29) | 7 (3) | 9 (5) |

| Variable . | Transplant year . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972-1999 . | 2000-2009 . | |||

| HLA-identical siblings . | HLA-matched unrelated donors . | HLA-identical siblings . | HLA-matched unrelated donors . | |

| Number of patients (% by period) | 260 (64) | 145 (36) | 211 (54) | 179 (46) |

| Age at diagnosis, no. (%) | ||||

| 0-5 y | 85 (33) | 54 (37) | 54 (26) | 64 (36) |

| 5-10 y | 106 (41) | 68 (47) | 97 (46) | 82 (46) |

| 10-20 y | 61 (23) | 20 (14) | 43 (20) | 27 (15) |

| >20 y | 8 (3) | 3 (2) | 17 (8) | 6 (3) |

| Age at transplant, no. (%) | ||||

| 0-10 y | 117 (45) | 70 (48) | 115 (55) | 100 (56) |

| 10-20 y | 126 (48) | 68 (47) | 73 (35) | 62 (35) |

| >20 y | 17 (7) | 7 (5) | 23 (11) | 17 (9) |

| Sex, no. (%) | ||||

| Female | 116 (45) | 72 (50) | 97 (46) | 90 (50) |

| Male | 143 (55) | 73 (50) | 112 (53) | 89 (50) |

| Unknown | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Donor/recipient sex, no. (%) | ||||

| Female/female | 63 (24) | 40 (28) | 53 (25) | 36 (20) |

| Female/male | 56 (22) | 31 (21) | 62 (29) | 22 (12) |

| Male/female | 51 (20) | 30 (21) | 43 (20) | 48 (27) |

| Male/male | 84 (32) | 39 (27) | 48 (23) | 66 (37) |

| Unknown | 6 (2) | 5 (3) | 5 (2) | 7 (4) |

| Donor/recipient CMV status, no. (%) | ||||

| Negative/negative | 47 (18) | 30 (21) | 19 (9) | 37 (21) |

| Negative/positive | 16 (6) | 19 (13) | 12 (6) | 33 (18) |

| Positive/negative | 15 (6) | 18 (12) | 10 (5) | 11 (6) |

| Positive/positive | 40 (15) | 22 (15) | 86 (41) | 32 (18) |

| Unknown | 142 (55) | 56 (39) | 84 (40) | 66 (37) |

| Bone marrow status before stem cell transplantation, no. (%) | ||||

| AA | 249 (96) | 133 (92) | 193 (91) | 162 (91) |

| MDS/AML | 11 (4) | 12 (8) | 18 (9) | 17 (9) |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, no. (%) | ||||

| ≤12 mo | 68 (26) | 22 (15) | 89 (42) | 47 (26) |

| >12 mo | 192 (74) | 123 (85) | 122 (58) | 132 (74) |

| Stem cell source, no. (%) | ||||

| BM | 242 (93) | 132 (91) | 140 (66) | 111 (62) |

| PB | 18 (7) | 13 (9) | 71 (34) | 67 (38) |

| Conditioning | ||||

| Missing conditioning, no. (%) | 30 (12) | 13 (9) | 9 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Fludarabine, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 215 (99) | 128 (98) | 90 (45) | 59 (34) |

| Yes | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 112 (55) | 115 (66) |

| Anti-T serotherapy, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 159 (64) | 43 (30) | 91 (45) | 63 (36) |

| Yes | 59 (24) | 88 (62) | 111 (55) | 111 (64) |

| Unknown | 30 (12) | 12 (8) | — | — |

| Irradiation, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 33 (13) | 11 (8) | 126 (62) | 100 (57) |

| TLI/TAI | 65 (26) | 31 (22) | 1 (<1) | 9 (5) |

| TBI* | 89 (36) | 80 (56) | 11 (5) | 21 (12) |

| No TBI, TLI/TAI unknown | 44 (18) | 14 (10) | 61 (30) | 38 (22) |

| Unknown | 17 (7) | 7 (5) | 3 (1) | 6 (3) |

| Ex-vivo T-cell manipulation, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 132 (53) | 55 (38) | 184 (91) | 142 (82) |

| Yes | 13 (5) | 47 (33) | 11 (5) | 23 (13) |

| Unknown | 103 (42) | 41 (29) | 7 (3) | 9 (5) |

Abbreviations: AA, aplastic anemia; CMV, cytomegalovirus; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; PB, peripheral blood stem cells; TAI, thoracoabdominal irradiation; TBI, total body irradiation; TLI, total lymphoid irradiation.

Doses for TBI were missing for 93/208 patients. Seven patients received 2 Gray, 94 received between 4 and 6 Gray, and 10 patients received 7 Gray or more.

Engraftment and GvHD

The probability of graft failure was 11% (95% confidence interval [CI], 9%-14%; 8% for primary and 3% for secondary graft failure). Engraftment rates according to donor type and transplantation period are shown in Table 2. The probability of graft failure was higher both in patients transplanted for clonal evolution (myelodysplastic syndrome or AML) than for aplastic anemia with only pancytopenia (hazard ratio [HR], 3.17; 95% CI, 1.60-6.28; P = .001) and in patients who received ex vivo T-cell-depleted graft (HR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.15-4.15; P = .017); it was lower in patients who had received a fludarabine-based regimen (HR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.12-0.78; P = .013) (supplemental Table 1; supplemental Table 2). Patients received mainly a cyclosporine-based GvHD prophylaxis regimen (>90%). Grade 2 to 4 acute GvHD was 32% (95% CI, 29%-36%), and chronic GvHD was 14% and 19% at 1 year and 5 years, respectively. CIF of GvHD (according to donor type and transplantation period) is shown in Table 2. In multivariate analysis, the only independent predictor for acute GvHD was the use of stem cells of an unrelated donor (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.08-1.87; P = .013). Fludarabine in the conditioning regimen was found to be protective (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.48-1.00; P = .048). Forty-one patients (17%) had at least 3 malformations with no association with a higher risk for acute GvHD. In multivariable analysis, independent predictors for chronic GvHD included HSCT in patients aged between 10 and 20 years (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.01-1.96; P = .045) and in patients older than 20 years (HR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.24-4.00; P = .008) or in patients with previous history of acute GvHD (HR, 3.40; 95% CI, 2.47-4.68; P < .0001).

Cumulative incidences of hematopoietic recovery, GvHD, NRM, and OS according to donor type and study period

| Variable . | Transplant year . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972–1999 . | 2000–2009 . | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings . | HLA-matched unrelated donors . | P . | HLA-identical siblings . | HLA-matched unrelated donors . | P . | |

| Graft failure | 14% (10-19) | 19% (13-26) | .24 | 6% (3-11) | 8% (4-13) | .69 |

| Acute GvHD 2-4 | .99* | .0003* | ||||

| 100 d | 37% (31-43) | 37% (29-45) | 19% (13-24) | 36% (28-43) | ||

| Chronic GvHD | .77* | .60* | ||||

| 12 mo | 15% (11-20) | 17% (11-24) | 11% (7-16) | 12% (7-18) | ||

| 60 mo | 18% (13-23) | 24% (17-32) | 20% (14-26) | 16% (11-23) | ||

| 180 mo | 32% (25-39) | 29% (20-37) | — | — | ||

| NRM | .0007* | .086* | ||||

| 12 mo | 22% (17-27) | 44% (35-52) | 14% (10-19) | 24% (18-31) | ||

| 60 mo | 27% (22-33) | 47% (38-56) | 19% (14-26) | 27% (20-35) | ||

| 180 mo | 40% (32-48) | 56% (46-65) | — | — | ||

| OS | <.0001† | .010† | ||||

| 12 mo | 75% (70-80) | 49% (41-58) | 83% (78-88) | 68% (61-75) | ||

| 60 mo | 68% (63-74) | 43% (36-52) | 76% (70-83) | 64% (57-72) | ||

| 180 mo | 55% (48-63) | 33% (25-43) | — | — | ||

| Variable . | Transplant year . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972–1999 . | 2000–2009 . | |||||

| HLA-identical siblings . | HLA-matched unrelated donors . | P . | HLA-identical siblings . | HLA-matched unrelated donors . | P . | |

| Graft failure | 14% (10-19) | 19% (13-26) | .24 | 6% (3-11) | 8% (4-13) | .69 |

| Acute GvHD 2-4 | .99* | .0003* | ||||

| 100 d | 37% (31-43) | 37% (29-45) | 19% (13-24) | 36% (28-43) | ||

| Chronic GvHD | .77* | .60* | ||||

| 12 mo | 15% (11-20) | 17% (11-24) | 11% (7-16) | 12% (7-18) | ||

| 60 mo | 18% (13-23) | 24% (17-32) | 20% (14-26) | 16% (11-23) | ||

| 180 mo | 32% (25-39) | 29% (20-37) | — | — | ||

| NRM | .0007* | .086* | ||||

| 12 mo | 22% (17-27) | 44% (35-52) | 14% (10-19) | 24% (18-31) | ||

| 60 mo | 27% (22-33) | 47% (38-56) | 19% (14-26) | 27% (20-35) | ||

| 180 mo | 40% (32-48) | 56% (46-65) | — | — | ||

| OS | <.0001† | .010† | ||||

| 12 mo | 75% (70-80) | 49% (41-58) | 83% (78-88) | 68% (61-75) | ||

| 60 mo | 68% (63-74) | 43% (36-52) | 76% (70-83) | 64% (57-72) | ||

| 180 mo | 55% (48-63) | 33% (25-43) | — | — | ||

Cumulative incidences were compared using Gray’s tests.

OS by log-rank tests.

Overall survival

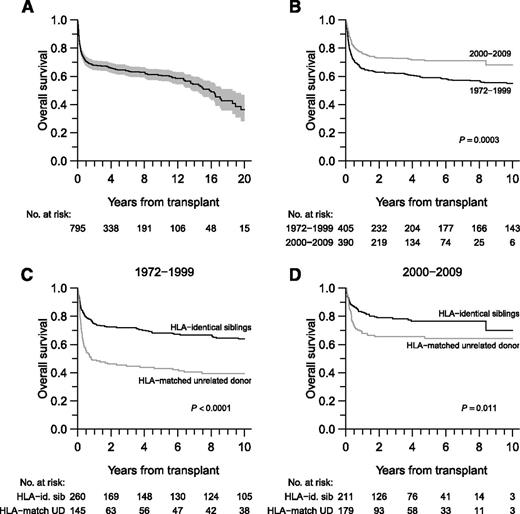

The OS probability was 65% (95% CI, 61%-68%) at 5 years, 52% (95% CI, 47%-58%) at 15 years, and 36% (95% CI, 28%-47%) at 20 years (Figure 1A). NRM was 24% (95% CI, 21%-28%) at 1 year and 29% (95% CI, 25%-32%) at 5 years. Concerning the 58 patients transplanted for AML or myelodysplastic syndrome, the cumulative incidence of relapse at 12 months was 7% (95% CI, 1%-22%) for patients with an HLA-identical sibling donor and 14% (95% CI, 4%-30%) for patients with HLA-matched unrelated donors. Cumulative incidences at 60 months were 7% (95% CI, 1%-22%) and 20% (95% CI, 7%-38%), respectively (P = .22). Improved OS was observed in patients transplanted after 2000 (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.50-0.81; P = .0003) (Figure 1B) or from a sibling donor (Figure 1C-D). NRM and OS are described by study period in Table 2.

OS. (A) OS in all patients. The shaded region represents the 95% point-wise CI. (B) OS according to study period. (C-D) OS according to donor type and transplantation period.

OS. (A) OS in all patients. The shaded region represents the 95% point-wise CI. (B) OS according to study period. (C-D) OS according to donor type and transplantation period.

During follow-up, 305 patients died. The principal 3 causes of death were GvHD (n = 105; 34%), infections (n = 83; 27%), and secondary malignancies (n = 30; 10%) (Table 3). The effects of stem cell source (peripheral blood vs bone marrow), as well as the presence of fludarabine, antithymocyte globulin, or total body irradiation within the conditioning regimen after 1999, are presented according to donor type in supplemental Figure 1. Factors associated with OS are shown in Table 4 (analysis on imputed datasets), as well as in supplemental Table 3 for analysis on the available data. Of note, the effect of donor type (sibling vs unrelated) was found to vary during follow-up. Patients with HLA-matched unrelated donors thus experienced a significantly higher hazard of death within the first year post–stem cell transplantation (SCT), whereas 1-year survivors showed a lower hazard of death long-term in this setting. However, survival for patients transplanted from an HLA-matched unrelated donor was clearly lower compared with for those who received an HLA-matched family donor on the entire follow-up period. Chronic GvHD and the occurrence of a secondary malignancy were independently associated with the hazard of death when considered as time-dependent covariates (HR, 3.10 [95% CI, 2.18-4.39; P < .0001] for chronic GvHD and HR, 23.0 [95% CI, 13.3-40.1; P < .0001]) for secondary malignancies. Regarding somatic malformations, patients with at least 3 malformations (n = 41; 17%) did not show any difference in terms of OS when compared with those whose malformations were limited (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.55-1.60; P = .81).

Causes of death according to study period in the overall population

| N (% of deaths) . | All patients . | 1972-1999 . | 2000-2009 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| GvHD | 105 (34) | 70 (35) | 35 (34) |

| Infection | 83 (27) | 52 (26) | 31 (30) |

| Toxicity | 19 (6) | 10 (5) | 9 (9) |

| Graft failure | 14 (5) | 10 (5) | 4 (4) |

| Relapse/progression | 10 (3) | 4 (2) | 6 (6) |

| Secondary malignancy | 30 (10) | 28 (14) | 2 (2) |

| Other | 28 (9) | 15 (7) | 13 (12) |

| Unknown | 16 (5) | 12 (6) | 4 (4) |

| N (% of deaths) . | All patients . | 1972-1999 . | 2000-2009 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| GvHD | 105 (34) | 70 (35) | 35 (34) |

| Infection | 83 (27) | 52 (26) | 31 (30) |

| Toxicity | 19 (6) | 10 (5) | 9 (9) |

| Graft failure | 14 (5) | 10 (5) | 4 (4) |

| Relapse/progression | 10 (3) | 4 (2) | 6 (6) |

| Secondary malignancy | 30 (10) | 28 (14) | 2 (2) |

| Other | 28 (9) | 15 (7) | 13 (12) |

| Unknown | 16 (5) | 12 (6) | 4 (4) |

Factors associated with OS (multivariable analysis on imputed datasets)

| Variables . | HR (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant | ||

| (0,10) | 1 | — |

| (10,20) | 1.39 (1.07-1.80) | .013 |

| (20,50) | 1.92 (1.25-2.94) | .003 |

| Donor/recipient sex | ||

| Female/female | 1 | — |

| Female/male | 0.86 (0.60-1.22) | .39 |

| Male/female | 1.01 (0.71-1.43) | .96 |

| Male/male | 0.84 (0.61-1.16) | .29 |

| Donor/recipient CMV status | ||

| Negative/negative | 1 | — |

| Negative/positive | 2.11 (1.34-3.33) | .001 |

| Positive/negative | 1.52 (0.93-2.50) | .096 |

| Positive/positive | 1.68 (1.10-2.57) | .016 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | ||

| ≤12 mo | 1 | — |

| >12 mo | 1.55 (1.14-2.12) | .005 |

| Donor | ||

| HLA-identical sibling | 1 | — |

| HLA-matched unrelated* | 1.57 (1.19-2.08) | .002 |

| Bone marrow status at SCT | ||

| AA | 1 | — |

| MDS/AML | 2.10 (1.41-3.11) | .0002 |

| Stem cell source | ||

| BM | 1 | — |

| PB | 1.15 (0.82-1.62) | .42 |

| SCT date | ||

| 1972-1999 | 1 | — |

| 2000-2009 | 0.80 (0.54-1.16) | .24 |

| Fludarabine in conditioning | ||

| No | 1 | — |

| Yes | 0.40 (0.26-0.64) | <.0001 |

| ATG in conditioning | ||

| No | 1 | — |

| Yes | 1.19 (0.89-1.58) | .24 |

| Irradiation | ||

| No | 1 | — |

| TAI/TLI/TBI* | ||

| 0-1 y posttransplant | 0.81 (0.53-1.23) | .32 |

| 1-5 y posttransplant | 1.11 (0.45-2.73) | .83 |

| >5 y posttransplant | 5.69 (1.48-21.8) | .011 |

| Ex-vivo T-cell manipulation | ||

| No | 1 | — |

| Yes | 1.40 (0.94-2.09) | .10 |

| Time-dependent variables | ||

| Chronic GVHD | 3.10 (2.18-4.39) | <.0001 |

| Secondary malignancy | 23.0 (13.3-40.1) | <.0001 |

| Variables . | HR (95% CI) . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant | ||

| (0,10) | 1 | — |

| (10,20) | 1.39 (1.07-1.80) | .013 |

| (20,50) | 1.92 (1.25-2.94) | .003 |

| Donor/recipient sex | ||

| Female/female | 1 | — |

| Female/male | 0.86 (0.60-1.22) | .39 |

| Male/female | 1.01 (0.71-1.43) | .96 |

| Male/male | 0.84 (0.61-1.16) | .29 |

| Donor/recipient CMV status | ||

| Negative/negative | 1 | — |

| Negative/positive | 2.11 (1.34-3.33) | .001 |

| Positive/negative | 1.52 (0.93-2.50) | .096 |

| Positive/positive | 1.68 (1.10-2.57) | .016 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | ||

| ≤12 mo | 1 | — |

| >12 mo | 1.55 (1.14-2.12) | .005 |

| Donor | ||

| HLA-identical sibling | 1 | — |

| HLA-matched unrelated* | 1.57 (1.19-2.08) | .002 |

| Bone marrow status at SCT | ||

| AA | 1 | — |

| MDS/AML | 2.10 (1.41-3.11) | .0002 |

| Stem cell source | ||

| BM | 1 | — |

| PB | 1.15 (0.82-1.62) | .42 |

| SCT date | ||

| 1972-1999 | 1 | — |

| 2000-2009 | 0.80 (0.54-1.16) | .24 |

| Fludarabine in conditioning | ||

| No | 1 | — |

| Yes | 0.40 (0.26-0.64) | <.0001 |

| ATG in conditioning | ||

| No | 1 | — |

| Yes | 1.19 (0.89-1.58) | .24 |

| Irradiation | ||

| No | 1 | — |

| TAI/TLI/TBI* | ||

| 0-1 y posttransplant | 0.81 (0.53-1.23) | .32 |

| 1-5 y posttransplant | 1.11 (0.45-2.73) | .83 |

| >5 y posttransplant | 5.69 (1.48-21.8) | .011 |

| Ex-vivo T-cell manipulation | ||

| No | 1 | — |

| Yes | 1.40 (0.94-2.09) | .10 |

| Time-dependent variables | ||

| Chronic GVHD | 3.10 (2.18-4.39) | <.0001 |

| Secondary malignancy | 23.0 (13.3-40.1) | <.0001 |

Nonproportional hazards were found (P = .028). An average adjusted effect of HLA-matched unrelated donor over the follow-up time is presented. Time-varying hazard ratios were 2.15 (95% CI, 1.57-2.95) 0-1 y post-SCT, 0.78 (95% CI, 0.36-1.68) 1-5 y post-SCT, and 0.37 (95% CI, 0.17-0.82) more than 5 y post-SCT.

Secondary malignancies

Overall, the 15-year CIF of secondary malignancies was 15% (95% CI, 11%-20%). For patients who survived more than 1 year (n = 509), the 15-year CIF was 21% (95% CI, 14%-28%); it was 34% (95% CI, 23%-46%) at 20 years (Figure 2). Solid tumors accounted for 89% of all secondary malignancies: 20 patients were diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma (mouth/tongue/esophagus for 13 patients, vulvo-vaginal for 1, lung for 1, and unspecified for 5), and 21 patients were diagnosed with solid tumor with localization missing. Others consisted of 1 patient with lymphoma, 4 with acute leukemia, and 4 with myelodysplastic syndromes. Independent risk factors for secondary malignancies included age at HSCT of between 10 and 20 years (HR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.27-4.25; P = .006) and older than 20 years (HR, 3.30; 95% CI, 1.05-10.3; P = .041), clonal evolution as an indication for HSCT (HR, 4.56; 95% CI, 1.67-12.5; P = .003), peripheral blood as source of stem cells (HR, 3.29; 95% CI, 1.30-8.35; P = .012), and previous chronic GvHD (time-dependent) (HR, 3.26; 95% CI, 1.81-5.88; P < .0001). Irradiation in the conditioning regimen and donor type did not correlate with secondary malignancies.

Cumulative incidence of death (blue) and secondary cancer (red) in 1-year survivors. The blue shadow region represents the 95% point-wise CI.

Cumulative incidence of death (blue) and secondary cancer (red) in 1-year survivors. The blue shadow region represents the 95% point-wise CI.

Discussion

This retrospective, multicenter study evaluated the outcome of 795 patients with FA who underwent a first allogeneic HSCT during the last 40 years in Europe. We documented a substantial reduction in the hazard of death related to allogeneic HSCT, as well as improved long-term survival in recent years (>1999), especially in patients transplanted from unrelated donors. Patients transplanted before the age of 10 years experienced lower risk for both chronic GvHD and secondary cancer, as well as better long-term OS. The use of a fludarabine-based conditioning regimen was associated with better engraftment, lower rate of acute GvHD, and eventually better long-term OS. Despite obvious improvement in recent years, the prospects for long-term survival in patients with FA after HSCT is still largely affected by secondary malignancies (of which 89% are solid tumors) directly associated with death. Age at HSCT and chronic GvHD, use of peripheral blood as source of the stem cells, and clonal evolution at the time of HSCT were identified as risk factors for secondary malignancies.

This study, spanning 40 years on almost 800 patients with FA who were transplanted in Europe, represents the largest group ever reported and offers a unique opportunity to describe and analyze HSCT practice as well as risk factors associated with outcomes in this rare disease. The median follow-up of 6 years may appear short regarding the 40-year study. However, the reason is that almost all patients transplanted before 1985 died within the 15 years of follow-up post-HSCT, and almost half of the population was transplanted after 2001. Overall, patients who were transplanted with stem cells from an HLA-identical sibling still have a better probability of survival than those transplanted with an unrelated transplant. The 5-year OS post-HSCT for patients transplanted from an HLA-identical sibling improved slightly over time (68% until the year 2000 compared with 76% thereafter). Conversely, the 5-year OS of patients transplanted after 1999 from an unrelated donor was 64%, which is much better than the 49% observed before this date and also compares favorably with results from other studies.7-9 This was mainly a result of decreased NRM after 1999.

Several modifications in our transplant practice might have contributed to this substantial reduction in the hazard of mortality, including improved supportive care, HLA typing,19,20,35-37 and possibly the use of fludarabine-based regimens, improving engraftment, decreasing acute GvHD, and eventually being associated with better OS. Factors other than donor type and fludarabine have been associated with detrimental OS and have been published, such as older age or clonal evolution at time of HSCT, a long delay from diagnosis to HSCT (>12 months), and donor/recipient cytomegalovirus status (negative/positive or positive/positive; for a review, see McMillan and Wagner38 ). The role of more accurate HLA allelic matching of unrelated donors in improving outcomes cannot be readily ascertained from these data, as only incomplete information on this factor was available in our patients.

Despite better HLA typing in recent years, the risk for GvHD did not change drastically and contributed either directly to early mortality or subsequently as a major risk factor for secondary cancer, as previously described.9,21,39 We did not find a correlation between malformations and acute GvHD, as previously suggested.7,21 Reducing acute GvHD would improve both early and late outcomes. Fludarabine was associated with a lower rate of acute GvHD in our study. Ex vivo as well as in vivo T-cell depletion has been shown to dramatically reduce the incidence of acute GvHD after related40 or unrelated transplantation8 in patients with FA. Prospective, randomized studies using antithymocyte globulin demonstrated a lower rate of both acute and chronic GvHD and may thus be of particular interest in this setting.41,42 A total body irradiation dose-escalation study associated with T-cell-depleted marrow grafts was not associated with increased toxicity, but rates of graft failure remained high.43 We also identified ex vivo T-cell depletion as a risk factor for graft failure in our study and found that the use of an irradiated-based conditioning regimen was associated here with poor long-term outcome. A fludarabine-based preparative regimen, which was associated with improved engraftment and better long-term OS, irradiation free, should currently be the optimal strategy to consider in patients with FA undergoing HSCT, by avoiding an additional risk factor interacting with the main biologic defect of FA (ie, DNA repair processes).

Although our study shows a drastic improvement in the risk for early mortality post-HCT, long-term OS was mainly affected by secondary malignancy. With a 6-year median follow-up, OS after HSCT was 49% at 20 years. A 4.4-fold higher rate of squamous cell carcinoma has been found compared with the rate seen in patients with FA of the same age who did not receive transplants.39 In the presence of competing causes of mortality, the cumulative incidence of squamous cell carcinoma is about 24% at 15 years.39 Whether the high incidence of posttransplantation head and neck carcinomas in patients with FA is related to the use of irradiation44-46 or to other intrinsic factors is still a matter of debate. Although patients with FA are inherently prone to developing tumors, chronic GvHD increased tumor risk.10,47 Previous studies reported an increased risk for GvHD with the use of peripheral blood stem cells after transplantation for acquired aplastic anemia.48,49 Although in our study no correlation with GvHD was found, the use of peripheral blood stem cells was strongly associated with secondary cancer. This result is important enough to consider marrow as the recommended source of stem cells in this particular population. We also identified older age by itself as an independent risk factor for secondary cancer. Obviously, age alone should not be considered to be an indication for HSCT, as it is not clear whether the higher incidence of cancer in patients transplanted after age 10 years was a result of older age at transplant or just older age itself in this particular setting.

Our work has strengths and limitations. The strengths include the large number of patients, registered in Europe, over a long period of time. Limits are mainly related to the retrospective nature of the study and the heterogeneity of conditioning regimens and supportive care, as well as changes in HSCT procedures during the study period. We especially faced the problem of completeness of the data, which is inherent to this type of analysis but offers the potential for the introduction of bias. To minimize this bias, we used the multiple imputations statistical method, which allowed us to create several data sets in which missing data are predicted. Because complementation group assignment and mutation testing are incomplete, we did not attempt to compare the genetic distributions or adjust for genetic factors. We were also not able to address directly the role of allelic HLA typing, and thus did not assess specific risk factors according to donor type subgroups (related vs unrelated donor). Moreover, we did not analyze in detail the group of patients with FA who were transplanted for clonal evolution (ie, AML or myelodysplastic syndrome) because a recent large survey has just been published by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research on this specific topic.50

In conclusion, we have found improved outcomes for patients with FA post-HSCT in recent years. Patients should be transplanted at a young age, with bone marrow as the source of stem cells, after a fludarabine-based conditioning regimen. Nevertheless, long-term survival in patients with FA after HSCT is still mainly affected by secondary malignancies, which supports the need for very long-term follow-up for these patients after HSCT. Chronic GvHD still represents the main risk factor for secondary malignancies and for late mortality.

Presented orally at the 53rd annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, December 10-13, 2011.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are particularly thankful to all centers from the Severe Aplastic Anemia Working Party and the Paediatric Diseases Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, who kindly agreed to participate in this study.

This work was supported in part by the Association Française pour la Maladie de Fanconi.

R.P.L. and R.P. have full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

Contribution: R.P.L., R.P., G.S., and C.D. conceived and designed the study; R.P.L., J.-H.D., M. Aljurf, E.T.K., J.S., R.W., V.M., J.S., M. Ayas, A.B., J.C.W.M., C.P., G.S., and C.D. provided study materials and patients; R.P.L., R.P., and G.S. collected and assembled the data; R.P.L., R.P., and G.S. analyzed and interpreted data; R.P.L., R.P., and G.S. wrote the manuscript; and R.P.L., J.-H.D., M. Aljurf, E.T.K., J.S., R.W., C.B., V.M., J.S., M. Ayas, R.O. A.B., J.C.W.M., C.P., G.S., and C.D. approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Régis Peffault de Latour, Service d’Hématologie Greffe, Hôpital Saint Louis, Paris, France; e-mail: regis.peffaultdelatour@sls.aphp.fr.

References

Author notes

R.P.L. and R.P. share first authorship.

G.S. and C.D. share last authorship.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal