Key Points

Mice expressing a talin(L325R) mutant that binds to, but does not activate integrin αIIbβ3, have impaired hemostasis.

Talin(W359A) reduces integrin binding, decelerates integrin activation and protects mice from thrombosis without pathological bleeding.

Abstract

Tight regulation of integrin affinity is critical for hemostasis. A final step of integrin activation is talin binding to 2 sites within the integrin β cytoplasmic domain. Binding of talin to a membrane-distal NPxY sequence facilitates a second, weaker interaction of talin with an integrin membrane-proximal region (MPR) that is critical for integrin activation. To test the functional significance of these distinct interactions on platelet function in vivo, we generated knock-in mice expressing talin1 mutants with impaired capacity to interact with the β3 integrin MPR (L325R) or NPLY sequence (W359A). Both talin1(L325R) and talin1(W359A) mice were protected from experimental thrombosis. Talin1(L325R) mice, but not talin(W359A) mice, exhibited a severe bleeding phenotype. Activation of αIIbβ3 was completely blocked in talin1(L325R) platelets, whereas activation was reduced by approximately 50% in talin1(W359A) platelets. Quantitative biochemical measurements detected talin1(W359A) binding to β3 integrin, albeit with a 2.9-fold lower affinity than wild-type talin1. The rate of αIIbβ3 activation was slower in talin1(W359A) platelets, which consequently delayed aggregation under static conditions and reduced thrombus formation under physiological flow conditions. Together our data indicate that reduction of talin-β3 integrin binding affinity results in decelerated αIIbβ3 integrin activation and protection from arterial thrombosis without pathological bleeding.

Introduction

Platelets are critical to stop bleeding and promote vessel repair at sites of vascular injury (hemostasis), but their pathological activation leads to the formation of intravascular thrombi and vessel occlusion (thrombosis). To contribute to hemostasis and thrombosis, platelets have to convert from an anti- to a proadhesive state, a switch that is dependent on cell surface integrins. Integrins are transmembrane αβ heterodimers that are normally expressed in a low-affinity binding state and, upon stimulation, undergo a conformational change that results in increased affinity for their ligand (inside-out activation). The most abundant integrin expressed in platelets (∼80 000 copies/platelet) is integrin αIIbβ3, a receptor for the multivalent ligands fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, and fibronectin. Genetic defects in either αIIb or β3 integrins (Glanzmann thrombasthenia) or pharmacologic inhibition of integrin αIIbβ3 cause impaired platelet aggregation and severe bleeding. Because of the excessive bleeding complications, antithrombotic intervention with αIIbβ3 inhibitors (abciximab, eptifibatide, or tirofiban) is recommended only in acute clinical settings and not for chronic administration.1

Integrin inside-out activation is tightly regulated by intracellular signaling pathways. When the endothelium is damaged, platelets are exposed to highly thrombogenic molecules (eg, collagen and thrombin). Platelet stimulation via either immunoglobulinlike or G protein–coupled receptors leads to the activation of the small-GTPase Ras-related protein 1 (Rap1), a critical molecular switch that directly regulates integrin activation.2-6 Mice deficient in Rap1b,7 the most abundant Rap isoform in platelets, or the main Rap-activator calcium and diacylglycerol-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor (CalDAG-GEFI)8 are characterized by impaired integrin activation in platelets, both in vitro and in vivo.

The β-integrin binding proteins talin and kindlin play critical roles in regulating integrin activation.9 Currently, the molecular mechanisms underlying kindlin-mediated integrin activation are unclear. In contrast, the signaling pathways that lead to talin-dependent integrin activation have been defined by structural, biochemical, and cell culture model systems. Downstream of Rap1, the binding of talin to the β-integrin cytoplasmic domain (tail) is both a sufficient and necessary final step for integrin activation.10,11 Talin is a ∼270 kDa cytoskeleton adaptor protein formed by a globular head region, consisting of a FERM (band 4.1, ezrin, radixin, moesin) domain and a flexible rod domain, that directly links integrins to the actin cytoskeleton.12,13 Recent structural and biochemical studies have established that integrin activation requires the talin head domain (THD) to engage 2 distinct binding sites within the integrin β tail.14,15 The talin FERM domain consists of F0, F1, F2, and F3 subdomains. The F3 subdomain has a phosphotyrosine-binding fold that binds with high affinity to an NPxY motif of the integrin β tail.16 This interaction facilitates talin binding to a second, weaker site in the membrane-proximal region (MPR) of the integrin. Talin binding to the integrin MPR is essential for talin-dependent integrin conformational change and activation.14,17

Global genetic deletion of talin1 in mice results in lethality at embryonic days 8.5 to 9.5 because of gastrulation defects.18 Selective deletion of talin1 in platelets and megakaryocytes (Tln1fl/flPf4-Cre+) blocks agonist-induced integrin activation, impairs thrombus formation, and results in profound defects in hemostasis.19,20 In this study, we sought to test the effects of talin mutants that selectively disrupt talin binding to the integrin MPR (L325R) or to the NPxY sequence (W359A) on thrombosis and hemostasis. Both (L325R) and (W359A) mutants have been reported to abolish talin-dependent integrin activation in Chinese hamster ovary cells.10,14,21 However, Nakazawa et al have recently shown in a human megarkaryoblastic cell line that talin(W359A) inhibits αIIbβ3 activation to a lesser degree than talin(L325R).22 Indeed, our results indicate that in platelets these talin mutants impart interesting functional differences. Platelet talin1(L325R) largely phenocopied the αIIbβ3 integrin activation and hemostatic defects observed in mice with talin-deficient platelets. In contrast, platelet talin1(W359A) mice showed decelerated αIIbβ3 activation and only modestly impaired hemostasis. Nonetheless, platelet talin1(W359A) mice were protected from arterial thrombosis. Together, our results demonstrate that partial inhibition of talin binding to the β3 integrin NPxY sequence imparts antithrombotic effects while preserving primary hemostasis.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Low-molecular-weight Lovenox (enoxaparin sodium; Sanofi-Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ), heparin-coated capillaries (VWR, West Chester, PA), bovine serum albumin (BSA, fraction V), prostacyclin (PGI2), and human fibrinogen (type I) (all from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); calcium sensing dye Fluo-4 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), protease-activated receptor 4–activating peptide (PAR4-AP) (Advanced Chemtech, Louisville, KY), 2-methylthio-AMP triethylammonium salt hydrate (2-MesAMP, P2Y12 inhibitor, BioLog, Bremen, Germany), U46619 (Cayman Chemical), fibrillar collagen type I (Chronolog, Havertown, PA), and RalGDS-RBD coupled to agarose beads and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Convulxin was purchased from Kenneth Clemetson (Theodor Kocher Institute, University of Berne, Switzerland). Monoclonal antibodies directed against GPIX or the activated form of murine αIIbβ3, JON/A-phycoerythrin (PE), were purchased from Emfret Analytics (Wuerzburg, Germany). Antibody against P-selectin conjugated to fluorescein iso-thiocyanate (FITC) was purchased from BD Biosciences (Rockville, MD). Antibody α-Rap1 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Mice

Conditional talin1-deficient mice (Tln1fl/flPf4-Cre+) and conditional talin1(L325R) mutant mice (Tln1L325R/flPf4-Cre+) and CalDAG-GEFI−/− mice have been described previously.8,17,19 A TGG to GCG mutation that results in an alanine substitution at amino acid W359 was introduced in Tln1, and conditional talin1(W359A) mutant mice (Tln1W359A/flPf4-Cre+) were generated as described previously.17 Mice were housed in the animal facilities of the University of California, San Diego, and of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Experimental procedures were approved by the Universities’ Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

Recombinant talin1 head domain (amino acids 1-433, THD) was prepared as described and has been previously shown to be homogeneously folded.11 THD was further purified on a Superdex200 size exclusion column, from which it eluted at a volume consistent with its monomeric molecular weight. SPR measurements were conducted using a revised protocol.23 Briefly, neutravidin was immobilized to a CM5 sensory chip via amine coupling. After blocking with 1M ethanolamine, biotinylated β3 tail24 was captured onto the sensor chip. A reference chamber was processed likewise but without β3 tail. Various concentrations of purified recombinant THD WT, THD(L325R), or THD(W359A) were injected into the chip, and the response curves, calculated as the difference between responses in the sample chamber and the reference chamber, were recorded to assess binding. The sensor chip was regenerated with 2M NaCl between measurements. The sensorgrams were fitted using a one-site binding model.

Hemostasis assays

The presence of fecal blood was detected with a guaiac-based hemoccult detection assay (Helena Laboratories) on freshly obtained stool samples.19 Tail bleeding assays were performed by resecting 1 mm of the tail, followed by immersion in 37°C isotonic saline as described previously.25 All experiments were terminated at 10 minutes by cauterizing the tail.

Ferric chloride–induced thrombosis

Ferric chloride(FeCl3)-induced thrombosis was performed as described previously26 by applying a 1.2 × 1.2-mm piece of filter paper soaked in 10% FeCl3 to each side of the common carotid artery of an anesthetized mouse. Time to vessel occlusion was determined using a Doppler flow probe after 3 minutes of application of FeCl3.

Flow cytometry

αIIbβ3 activation and α-granule secretion—dose-response assay.

Washed platelets were diluted (108 platelets/mL) in Tyrode’s solution containing 1 mM CaCl2 and activated with increasing concentrations of convulxin or PAR4-AP in the presence of JON/A-PE (2 μg/mL)27 and α-P-selectin-FITC (2 μg/mL). After 10 minutes of incubation, each sample was further diluted to 1 mL and analyzed immediately with a BD Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer.

αIIbβ3 activation—Real-time assay.

Washed platelets were diluted (1.25 × 107 platelets/mL) in Tyrode’s solution containing 1 mM CaCl2. After establishing a baseline with unlabeled platelets, JON/A-PE (5 μg/mL) and Par4-AP (600 μM) were added simultaneously in an equal volume of Tyrode’s solution to allow for efficient mixing. Jon/A-PE binding was recorded continuously for 10 minutes with a BD Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer. The data were adjusted by subtracting at each time point the Jon/A-PE binding of an unstimulated sample. The maximum velocity of integrin αIIbβ3 activation was quantified with R studio by fitting the data to a loess function and calculating the maximal rate of change of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) over time (ΔMFI/minute).

Calcium flux measurement.

Washed platelets were incubated with 5 µmol/L Fluo-4 (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes, diluted in Tyrode’s solution (5 × 107 platelets/mL) containing 1 mM CaCl2, activated with Par4-AP (600 μM), and analyzed for fluorescence (FL)1 intensity over a period of 5 minutes.

Flow chamber studies

In vitro flow studies were performed in a poly dimethylsiloxane microfluidic device. Fabrication of microfluidic devices and microfluidic collagen patterning were performed as previously described.28 Briefly, a 500-μm strip of fibrillar collagen type I (200 μg/mL) was deposited along the length of a glass slide. A poly dimethylsiloxane device with 7 flow channels (width 250 μm, height 60 μm, length 6 mm) was oriented perpendicular to the patterned collagen. Murine whole blood was drawn from the retro-orbital plexus into heparinized tubes (30 U/mL Lovenox), incubated with 4 μg/mL of anti–GPIX-Alexa488, and infused using a continuous flow syringe pump at arterial (1200–S) or venous (100–S) wall shear rates for 10 minutes. Adhesion of platelets was monitored continuously with a Nikon TE300 microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) equipped with a QImaging Retiga Exi CCD camera (QImaging, Surrey, Canada). Images were acquired and analyzed using Slidebook software version 5.0.0.34x64.

Statistics

Results are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and statistical significance was assessed by two-way analysis of variance unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance of tail bleeding times and volumes were analyzed with a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn multiple comparisons post-hoc test. Hemoccult assay results were analyzed with the Fisher exact test. A P value < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Disruption of specific talin-integrin interactions in vivo

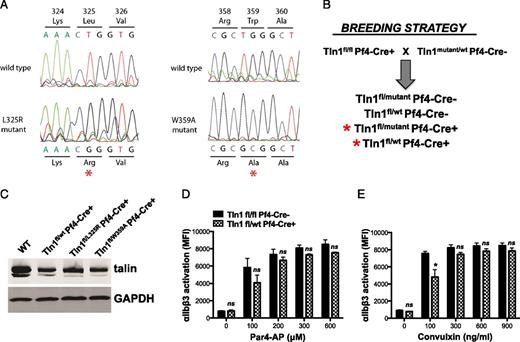

To study the effects of selectively blocking either talin-integrin binding or talin-dependent integrin activation on platelet adhesion, we generated mice with single amino acid substitutions W359A or L325R, respectively, in TALIN1 by gene targeting17 (Figure 1). Similar to the systemic knockout of talin,18 we found that homozygous expression of either one of the talin mutants was embryonic lethal in mice, whereas heterozygotes obtained at expected ratios were fertile and showed no obvious defects. To circumvent the embryonic lethality, Tln1(W359A/wt) or Tln1(L325R/wt) mice were crossed with Tln1fl/flPf4-Cre+ mice to generate compound heterozygous (Tln1W359A/fl PF4-Cre+ and Tln1L325R/fl PF4-Cre+) and control mice (Tln1wt/fl PF4-Cre+). Platelets from mutant and control mice expressed similar amounts of talin1 protein albeit at approximately 50% the levels of wild-type mouse platelets (Figure 1C). Reduced levels of talin protein in Tln1wt/fl Cre+ platelets had minimal effects on αIIbβ3 integrin function relative to Tln1fl/fl Cre– platelets (Figure 1D-E).

Generation of mice expressing talin1 mutants in platelets. (A) Sequencing chromatograms of mutated regions of Tln1(L325R) and Tln1(W359A) ES cells. Genomic DNA isolated from targeted ES cells was used as a template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers that amplified the mutated sequences, and PCR amplicons were sequenced. (B) Mouse breeding strategy to obtain mice with Tln1(L325R) and Tln1(W359A) expressing platelets. (C) Western blot analysis showing similar levels of talin expression in control (Tln1wt/flCre+) and mutant (Tln1L325R/flCre+ and Tln1W359A/flCre+) platelets. Par4-AP (D) or convulxin-induced (E) αIIbβ3-integrin activation (JON/A-PE binding). Reduced levels of talin1 protein in Tln1WT/fl Cre+ platelets had minimal effect relative to Tln1fl/fl Cre– platelets. Bar graphs represent MFI ± SEM (n = 6, 3 independent experiments). *P < .05.

Generation of mice expressing talin1 mutants in platelets. (A) Sequencing chromatograms of mutated regions of Tln1(L325R) and Tln1(W359A) ES cells. Genomic DNA isolated from targeted ES cells was used as a template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers that amplified the mutated sequences, and PCR amplicons were sequenced. (B) Mouse breeding strategy to obtain mice with Tln1(L325R) and Tln1(W359A) expressing platelets. (C) Western blot analysis showing similar levels of talin expression in control (Tln1wt/flCre+) and mutant (Tln1L325R/flCre+ and Tln1W359A/flCre+) platelets. Par4-AP (D) or convulxin-induced (E) αIIbβ3-integrin activation (JON/A-PE binding). Reduced levels of talin1 protein in Tln1WT/fl Cre+ platelets had minimal effect relative to Tln1fl/fl Cre– platelets. Bar graphs represent MFI ± SEM (n = 6, 3 independent experiments). *P < .05.

Thrombosis and hemostasis in talin mutant mice

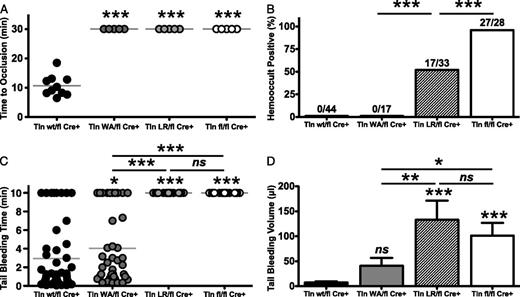

Mice with talin-deficient platelets or mutations in αIIbβ3 integrin that preclude talin binding are protected from thrombosis.19,26 To test the effect of talin mutants on thrombosis, Tln1W359A/flCre+ and Tln1L325R/flCre+ mice were subjected to a FeCl3-induced thrombosis model in the carotid artery (Figure 2A). In control mice (Tln1wt/flCre+), complete occlusion of the vessel occurred 10.7 ± 3.6 minutes after application of 10% FeCl3. In contrast, both Tln1L325R/flCre+ and Tln1W359A/flCre+ mice failed to form occlusive thrombi at any point in the experiment. A 50% reduction of talin expression in platelets had no effect on occlusion times in this model (supplemental Figure 2 available on the Blood Web site). Mice with talin-deficient platelets exhibit chronic spontaneous gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, with 95% of Tln1fl/flCre+ mice testing positive for fecal blood.19 Importantly, GI bleeding was also observed in Tln1L325R/flCre+ but not Tln1W359A/flCre+ mice (Figure 2B). We further examined the ability of these mice to achieve hemostasis after injury. In a tail-bleeding assay, talin-deficient and Tln1L325R/flCre+ mice bled continuously during the 10 minutes after tail resection. In contrast, bleeding times were modestly prolonged in Tln1W359A/flCre+ compared with control mice (4.4 ± 4.0 and 2.5 ± 3.4 minutes, respectively; P = .042) (Figure 2C). To more quantitatively evaluate the bleeding risk in the various groups, we measured the volume of blood lost after injury (Figure 2D). Animals in all study groups lost more blood than control mice. However, Tln1W359A/flCre+ mice lost significantly less blood than talin-deficient or Tln1L325R/flCre+ mice, suggesting that platelets expressing Tln1(W359A) support the formation of hemostatically functional thrombi. Differences in hemostatic and thrombotic function observed in talin mutant mice were not ascribable to differences in platelet counts because these were similar among all experimental groups (data not shown). Collectively, our results show that although platelet talin mutant mice were equally protected from thrombosis, Tln1W359A/flCre+ mice exhibit markedly better hemostatic function relative to Tln1L325R/flCre+ mice.

Analysis of thrombosis and hemostasis in talin1 mutant mice. (A) Tln1W359A/fl Pf4-Cre+ (Tln1WA/flCre+) and Tln1L325R/fl Pf4-Cre+ (Tln1LR/flCre+) mice are protected from FeCl3-induced thrombosis of the carotid artery. Time to vessel occlusion was determined using a Doppler flow probe after 3 minutes of application of 10% FeCl3. (B) The incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in talin mutant and control mice was determined using a guaiac-based hemoccult test. Numbers of hemoccult-positive/total mice are shown for each group. (C) Bleeding times and (D) blood loss volume in the indicated mice after tail resection (n = 17-56 mice/group). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Analysis of thrombosis and hemostasis in talin1 mutant mice. (A) Tln1W359A/fl Pf4-Cre+ (Tln1WA/flCre+) and Tln1L325R/fl Pf4-Cre+ (Tln1LR/flCre+) mice are protected from FeCl3-induced thrombosis of the carotid artery. Time to vessel occlusion was determined using a Doppler flow probe after 3 minutes of application of 10% FeCl3. (B) The incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in talin mutant and control mice was determined using a guaiac-based hemoccult test. Numbers of hemoccult-positive/total mice are shown for each group. (C) Bleeding times and (D) blood loss volume in the indicated mice after tail resection (n = 17-56 mice/group). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

αIIbβ3 integrin activation is partially impaired in platelets expressing Tln1(W359A)

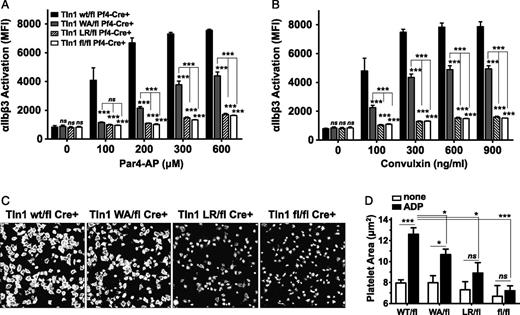

To understand why hemostasis is different in the 2 talin mutant strains, we next tested whether Tln1(W359A) and Tln1(L325R) could support the activation of αIIbβ3 integrin. Platelets from mutant or control mice were stimulated with increasing concentrations of agonist to the thrombin receptor, Par4 (Figure 3A), or to the collagen receptor, GPVI (convulxin; Figure 3B), and αIIbβ3 activation was quantified by measuring binding of the activation-specific αIIbβ3 antibody, Jon/A-PE.27 Integrin activation of Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets was significantly reduced, but not abolished, compared with controls. Conversely, integrin activation of Tln1L325R/flCre+ or Tln1fl/flCre+ platelets was completely inhibited, even in response to high doses of agonist (Figure 3). Mouse platelets must be exogenously stimulated to efficiently spread on immobilized fibrinogen.26,29 Thus as an independent measure of αIIbβ3 activation in talin mutant platelets, we quantified platelet spreading on fibrinogen-coated coverslips in response to stimulation with 100 μM adenosine diphosphate (ADP). Tln1L325R/flCre+ and Tln1fl/flCre+ platelets failed to spread, whereas ADP-treated Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets extended lamellipodia and significantly increased their surface area compared with unstimulated platelets, albeit to a lesser extent than Tln1wt/flCre+ controls (Figure 3C-D). Compared with integrin activation, granule release as measured by surface P-selectin was only minimally affected in platelets from talin mutant mice (supplemental Figure 1). Together these data indicate that αIIbβ3 integrin activation is critically dependent on the capacity of talin to interact with the β3 integrin MPR regions. Furthermore, αIIbβ3 integrin activation is reduced, but not abolished, in Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets, providing a cellular basis for the modest impairment in hemostatic function of Tln1W359A/flCre+ mice.

Platelets expressing talin1(W359A) exhibit partially impaired αIIbβ3 activation. (A-B) αIIbβ3-integrin activation (JON/A-PE binding) was measured in washed platelets isolated from mice with the indicated genotypes. Platelets were stimulated for 10 minutes with increasing concentrations of Par4-AP (A) or convulxin (B), stained with JON/A-PE, and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Bar graphs represent MFI ± SEM (n = 6, 3 independent experiments). (C) Representative images of rhodamine-phalloidin–stained talin1 mutant platelets spread on fibrinogen-coated glass in the presence of 100 μM ADP for 45 minutes. (D) Quantitation of platelet area (μm2); n = 5 independent experiments; mean ± SEM. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Platelets expressing talin1(W359A) exhibit partially impaired αIIbβ3 activation. (A-B) αIIbβ3-integrin activation (JON/A-PE binding) was measured in washed platelets isolated from mice with the indicated genotypes. Platelets were stimulated for 10 minutes with increasing concentrations of Par4-AP (A) or convulxin (B), stained with JON/A-PE, and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. Bar graphs represent MFI ± SEM (n = 6, 3 independent experiments). (C) Representative images of rhodamine-phalloidin–stained talin1 mutant platelets spread on fibrinogen-coated glass in the presence of 100 μM ADP for 45 minutes. (D) Quantitation of platelet area (μm2); n = 5 independent experiments; mean ± SEM. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

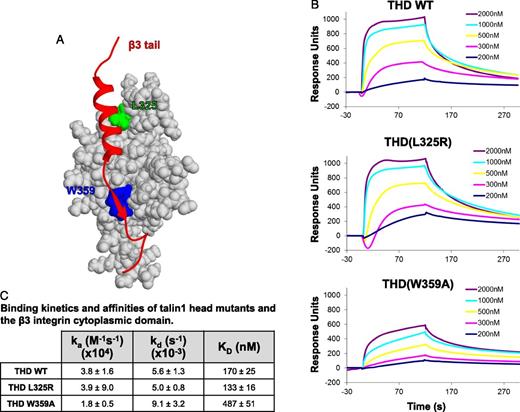

Reduced binding affinity of Tln1(W359A), but not Tln1(L325R), for β3 tail

To quantitatively measure the effects of talin1(L325R) and talin1(W359A) mutations on talin-integrin interaction, we measured the affinities between wild-type or mutant THD and the integrin β tail by surface plasmon resonance. Wild-type THD bound to immobilized β3 tail with a KD = 170 ± 25 nmol/L, a value that is consistent with that obtained by nuclear magnetic resonance.15 THD(L325R), which does not affect the strong NPxY interaction that contributes most of the binding free energy,14 had a similar affinity for β3 integrin as wild-type THD (Figure 4). THD(W359A) bound to β3, albeit with 2.9-fold lower affinity than THD(WT) (Figure 4). These results support the concept that the talin1(L325R) mutant binds normally to β integrins and is selectively defective in activating integrins. In addition, our results indicate that the inhibition of β3 integrin binding by talin1(W359A) is only partial and explains the modest reduction in αIIbβ3 integrin activation observed in talin1(W359A) platelets.

Talin1(W359A), but not talin1(L325R), impairs binding of talin to the β3 integrin tail. (A) Representation of the β3 integrin-talin complex structure (PDB 2H7E). Shown in red is the ribbon view of the β3 tail; light gray is the surface view of the talin F3 subdomain. Talin residues leucine 325 (L325) and tryptophan 359 (W359) are shown in green and blue, respectively. (B) Representative BiaCORE sensorgrams of THD binding to immobilized β3-integrin cytoplasmic domain (tail). Biotinylated β3 tail was immobilized to a neutravidin sensor chip. Indicated concentrations of wild-type or mutant talin head were injected, and response curves were measured as the difference between the experimental chamber and a reference chamber lacking immobilized β3 integrin. (C) Association rate constants (ka), dissociation rate constants (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) between β3-integrin tail and THD mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Talin1(W359A), but not talin1(L325R), impairs binding of talin to the β3 integrin tail. (A) Representation of the β3 integrin-talin complex structure (PDB 2H7E). Shown in red is the ribbon view of the β3 tail; light gray is the surface view of the talin F3 subdomain. Talin residues leucine 325 (L325) and tryptophan 359 (W359) are shown in green and blue, respectively. (B) Representative BiaCORE sensorgrams of THD binding to immobilized β3-integrin cytoplasmic domain (tail). Biotinylated β3 tail was immobilized to a neutravidin sensor chip. Indicated concentrations of wild-type or mutant talin head were injected, and response curves were measured as the difference between the experimental chamber and a reference chamber lacking immobilized β3 integrin. (C) Association rate constants (ka), dissociation rate constants (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) between β3-integrin tail and THD mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Decelerated αIIbβ3 activation in platelets expressing Tln1(W359A)

To test whether the 2.9-fold lower affinity of Tln1(W359A) for β3 integrin affected the efficiency of talin recruitment and thereby the speed of αIIbβ3 activation, we used a real-time flow cytometry assay for the quantitative assessment of the kinetics of αIIbβ3 activation in mouse platelets.27 JON/A-PE and the agonist Par4-AP were added simultaneously to washed platelets, and binding of JON/A-PE was monitored continuously for 10 minutes by flow cytometry (Figure 5A). Consistent with the results shown in Figure 3, Tln1L325R/flCre+ and Tln1fl/flCre+ platelets failed to activate αIIbβ3, whereas integrin activation in Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets was reduced by ∼50% compared with control (Tln1wt/flCre+) 10 minutes after addition of the agonist (Figure 5A). To differentiate the rate of Jon/A-PE binding from an overall reduction in the amount of Jon/A-PE bound by Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets, real-time Jon/A-binding was normalized to the maximum amount of Jon/A-PE bound within each group. Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets showed a slower rate of αIIbβ3 integrin activation and a 65% reduction in the maximum velocity of activation (Figure 5B-C). We recently reported a significant delay in αIIbβ3 activation for platelets lacking the Rap-GEF, CalDAG-GEFI.30-32 To better understand how Tln1(W359A) affected integrin activation kinetics, we compared Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets to platelets lacking CalDAG-GEFI. CalDAG-GEFI−/−8 platelets did not bind JON/A-PE within the first 3 minutes of cellular activation (Figure 5A), confirming that CalDAG-GEFI is critical for the very rapid activation of Rap1 and αIIbβ3 integrin.28 JON/A-PE binding to stimulated Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets occurred without a lag phase, indicating that (1) signaling upstream of talin is normal in these cells and (2) the slower kinetics of αIIbβ3 activation are likely explained by the significantly lower Ka measured for the interaction between Tln(W359A) head domain and the β3 tail (Figure 4C).

Expression of talin1(W359A) causes decelerated αIIbβ3 activation in platelets. The kinetics of αIIbβ3 activation were assessed in real time by flow cytometry. Jon/A-PE and Par4-AP were added simultaneously (arrow) to platelets of the indicated genotype. Jon/A-PE binding (integrin activation) was monitored continuously for 10 minutes. Tln1W359A/flCre+ (Tln1WA/flCre+) platelets were compared with (A) Tln1wt/wtCre+(WT), Tln1wt/flCre+, Tln1fl/flCre+, and Tln1L325R/flCre+ (Tln1LR/flCre+) platelets, and CalDAG-GEFI−/− (CDGI−/−) platelets. Traces are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Real-time Jon/A-PE binding data are shown normalized for maximum binding within each group. Maximum values for the indicated groups were calculated as the average MFI over the final 10 seconds of the 10-minute assay. (C) Maximum velocity of αIIbβ3 activation, determined as the maximal rate of change of MFI over time (ΔMFI/minute). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Expression of talin1(W359A) causes decelerated αIIbβ3 activation in platelets. The kinetics of αIIbβ3 activation were assessed in real time by flow cytometry. Jon/A-PE and Par4-AP were added simultaneously (arrow) to platelets of the indicated genotype. Jon/A-PE binding (integrin activation) was monitored continuously for 10 minutes. Tln1W359A/flCre+ (Tln1WA/flCre+) platelets were compared with (A) Tln1wt/wtCre+(WT), Tln1wt/flCre+, Tln1fl/flCre+, and Tln1L325R/flCre+ (Tln1LR/flCre+) platelets, and CalDAG-GEFI−/− (CDGI−/−) platelets. Traces are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Real-time Jon/A-PE binding data are shown normalized for maximum binding within each group. Maximum values for the indicated groups were calculated as the average MFI over the final 10 seconds of the 10-minute assay. (C) Maximum velocity of αIIbβ3 activation, determined as the maximal rate of change of MFI over time (ΔMFI/minute). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

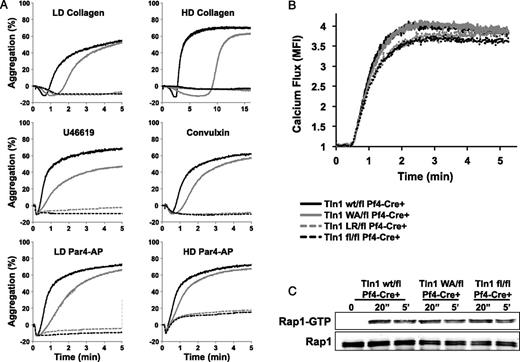

Impaired aggregate formation of Tln1(W359A) platelets

To examine the ability of talin mutant platelets to form aggregates, we stimulated washed platelets in a standard optical aggregometer with various agonists in the presence of 50 μg/mL fibrinogen and 1 mM CaCl2 (Figure 6A). Both Tln1L325R/flCre+ and Tln1fl/flCre+ platelets failed to aggregate in response to collagen, convulxin, the thromboxane A2 analog U46619, or Par4-AP. In contrast, Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets aggregated in response to all agonists tested. However, a delay in the aggregation of Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets was consistently observed, particularly at low doses of agonist. To confirm that this delay in aggregation was not caused by a defect in signaling events upstream of talin, we examined intracellular calcium mobilization and Rap1 activation in resting and activated platelets. Par4-AP–induced release of calcium from intracellular stores was comparable for all genotypes (Figure 6B). Similarly, the levels of Rap1-GTP were comparable in lysates of activated control and talin mutant platelets, both 20 seconds and 5 minutes after addition of the agonist (Figure 6C). Thus, the delay in integrin-dependent aggregation observed in Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets is likely attributable to slower αIIbβ3 integrin activation kinetics. Reduced αIIbβ3 activation, however, did not affect the size of Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelet aggregates formed in static conditions as measured by light transmission.

Delayed aggregation in platelets expressing talin1(W359A). (A) Aggregation response of washed Tln1wt/flCre+ (black line), Tln1W359A/flCre+ (gray line), Tln1L325R/flCre+ (gray dashed line), and Tln1fl/flCre+ platelets (black dashed line) stimulated with 5 μg/mL (LD) collagen, 25 μg/mL (HD) collagen, 1 μM U46619, 200 ng/mL convulxin, 200 μM (LD), or 600 μM (HD) Par4-AP. (B) Calcium mobilization in platelets labeled with the calcium-sensitive dye Fluo-4 and stimulated with Par4-AP in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+. (C) Time course of Rap1 activation in platelets stimulated with Par4-AP. The bottom panel shows total Rap1 as a loading control. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Delayed aggregation in platelets expressing talin1(W359A). (A) Aggregation response of washed Tln1wt/flCre+ (black line), Tln1W359A/flCre+ (gray line), Tln1L325R/flCre+ (gray dashed line), and Tln1fl/flCre+ platelets (black dashed line) stimulated with 5 μg/mL (LD) collagen, 25 μg/mL (HD) collagen, 1 μM U46619, 200 ng/mL convulxin, 200 μM (LD), or 600 μM (HD) Par4-AP. (B) Calcium mobilization in platelets labeled with the calcium-sensitive dye Fluo-4 and stimulated with Par4-AP in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+. (C) Time course of Rap1 activation in platelets stimulated with Par4-AP. The bottom panel shows total Rap1 as a loading control. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

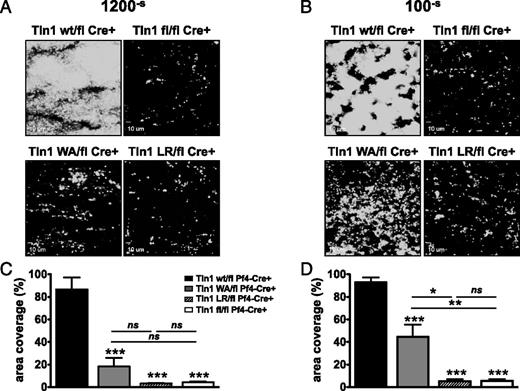

Rapid integrin activation is critical for platelet adhesion under fluid shear stress conditions, especially those observed in arterioles and arteries.28 Therefore, we examined the ability of talin mutant platelets to adhere to collagen and form aggregates ex vivo under controlled conditions of flow (Figure 7). Interestingly, Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets exhibited a profound adhesion defect at both low and high shear rates. At arterial (1200–s) shear rates, accumulation of Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets on collagen was not significantly different from that of talin-deficient cells (Figure 7A,C). At low venous shear rates (100–s) however, Tln1W359A/flCre+, but not Tln1L325R/flCre+ or Tln1fl/flCre+ platelets, could support the generation of small 3-dimensional thrombi (Figure 7B,D).

The effects of fluid shear stress on talin1 mutant platelet thrombus formation ex vivo. Platelets in heparinized whole blood were labeled with anti–GPIX-Alexa488 and perfused over fibrillar collagen type I at low (100–s) or high (1200–s) shear rates. Adhesion of platelets was monitored continuously with a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). (A-B) Representative images of platelet adhesion after 10 minutes of perfusion. (C-D) Image analysis. Platelet adhesion over collagen was quantified by measuring surface area coverage (percentage of total area) with Slidebook 5.0 software. Graphs show mean ± SEM (6 independent experiments). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

The effects of fluid shear stress on talin1 mutant platelet thrombus formation ex vivo. Platelets in heparinized whole blood were labeled with anti–GPIX-Alexa488 and perfused over fibrillar collagen type I at low (100–s) or high (1200–s) shear rates. Adhesion of platelets was monitored continuously with a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). (A-B) Representative images of platelet adhesion after 10 minutes of perfusion. (C-D) Image analysis. Platelet adhesion over collagen was quantified by measuring surface area coverage (percentage of total area) with Slidebook 5.0 software. Graphs show mean ± SEM (6 independent experiments). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Discussion

Talin binding to the β integrin tail is a key final step in integrin activation.10 Results from in vitro structure-function studies have provided the basis for a model of talin-induced integrin activation in which 2 sites within the THD interact with a membrane distal NPxY site and an MPR of β integrins.14 Here we have tested the requirement of these distinct talin-integrin interactions for platelet function. Disruption of the interaction between talin and the MPR region (Tln1L325R/flCre+ mice) virtually abolished talin-dependent αIIbβ3 activation in platelets, both in vitro and in vivo. In contrast, mice expressing talin1(W359A) exhibited only a modest reduction in hemostatic function, yet were completely protected from FeCl3-induced thrombosis. In-depth mechanistic studies further demonstrated that (1) integrin activation is significantly delayed in Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets, (2) this defect is not the result of impaired upstream signaling but likely reflects the lower binding affinity of talin1(W359A) for β3, and (3) the delay in αIIbβ3 integrin activation results in strongly impaired thrombus formation ex vivo, especially under conditions of high shear stress. Together, our results show that manipulating the talin-αIIbβ3 integrin interaction can produce desirable antithrombotic effects while largely preserving hemostasis in mice.

Megakaryocyte/platelet-specific deletion of talin in mice nearly abolishes integrin activation in platelets and causes chronic pathological bleeding associated with anemia and reduced survival.19 Here we report a similar phenotype for mice expressing talin1(L325R). However, spontaneous bleeding was less severe in Tln1L325R/flCre+ mice when compared with Tln1fl/flCre+ mice, suggesting that talin may serve other functions in hemostasis. For example, platelets require talin to mechanically link integrins to the actin cytoskeleton during fibrin clot retractions.17 Second, talin is a known binding partner of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase γ (PIP5KIγ)33 and this complex is speculated to participate in maintaining plasma membrane integrity.19,34 Importantly, whereas the talin1(L325R) lacks the capacity to activate integrins, it retains the capacity to bind the β3-integrin tail (Figure 4), to bind PIP5KIγ,17 and to mechanically link αIIbβ3 to the actin cytoskeleton during clot retraction.17 Finally, it is possible that talin may participate in integrin outside-in signaling by either promoting integrin clustering and/or acting as an adapter for signaling pathways downstream of integrins such as focal adhesion kinase.35

Partial inhibition of talin-integrin binding led to slower αIIbβ3-integrin activation in Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets. Previous in vitro studies, however, reported that the W359A talin mutation abolishes talin-induced integrin activation by strongly inhibiting talin binding to the β-integrin tail.10,21 There are several possible reasons for the differences in results. First, previous analyses of talin(W359A) binding to β integrin were done using affinity chromatography.21 Here, using the more sensitive and quantitative technique of surface plasmon resonance, we show that talin head(W359A) binds to β3 with a 2.9-fold lower affinity than wild-type talin head. The weakened talin-integrin binding is likely sufficient to facilitate delayed αIIbβ3-integrin activation and hemostasis in Tln1W359A/flCre+ mice. Second, many in vitro studies use only THD or fragments thereof that lack the rod domain that contains multiple actin binding sites as well as a second integrin binding site.36,37 Thus it is possible that the (W359A) mutation may have relatively less effect on talin function in the context of the full-length protein. Indeed, full length talin1(W359A) partially rescued cell spreading of talin-deficient endothelial cells.38 Third, talin is highly expressed in platelets (comprising 3%-5% of the total cellular protein39 ) and it is recruited to the plasma membrane of activated platelets.40 Thus, a strong defect in talin function may be partially compensated for in platelets by the high local concentration of talin at the membrane. The latter hypothesis may also help explain why mice homozygous for the talin1(W359A) mutation die during embryonic development, even though this mutant shows significant activity in platelets. Further studies will be required to substantiate whether this mutant has more profound functional defects in certain cellular contexts.

Tln1W359A/flCre+ mice were protected from FeCl3-induced thrombosis, yet they showed only mild defects in hemostasis (Figure 2). In vitro, Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets formed aggregates under static conditions, albeit at a delayed rate (Figure 6). Furthermore, platelet adhesion to collagen was more profoundly impaired at high shear rates (1200–s) compared with low shear rates (100–s) (Figure 7). The finding that Tln1W359A/flCre+ platelets form aggregates in low-flow, but not in high-flow, conditions supports the concept that blocking talin-integrin binding at the level of the NPXY motif impairs the ability of the integrin to activate rapidly, which is critical to ensure platelet adhesion in the conditions of fluid shear stress, especially those observed in arterioles and arteries. Confirmation for this conclusion comes from our studies on the platelet Rap activator, CalDAG-GEFI. Mice lacking CalDAG-GEFI, a Rap activator, also exhibit delayed platelet αIIbβ3 activation, markedly impaired thrombus formation at arterial shear rates, and partially retained hemostatic function.28,30,31 Together these studies suggest that deceleration of αIIbβ3 activation could be a safe strategy to prevent arterial thrombosis.

In summary, our results show that disruption of talin interactions with either the MPR or NPxY sequence of β3 integrin impairs αIIβ3-integrin activation in vivo and has potent antithrombotic effects. First, mice with talin1(L325R) platelets phenocopy the near complete inhibition of agonist-induced αIIbβ3 integrin activation and strongly impaired hemostasis observed in mice with talin-deficient platelets, despite normal binding affinity of talin1(L325R) for β3 integrin. Second, we report the unexpected result that a talin1(W359A) mutant partially impairs binding of talin to β3 integrin and reduces the rate and magnitude of αIIbβ3 activation in platelets. Importantly, mice expressing talin1(W359A) in platelets are protected from arterial thrombosis, yet they have only minimally impaired hemostasis. Our findings suggest that slowing the kinetics of αIIbβ3 integrin through manipulating talin-β3 integrin interactions could provide a useful therapeutic approach in treating thrombotic disease.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark Ginsberg for helpful discussions and support, Rod McEver and Mark Ginsberg for critical reading of the manuscript, and David Critchley and Radek Skoda for generously providing the talin floxed mice and PF4-Cre mice, respectively.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grants R01 HL078784, HL117061 (B.P.) and HL094594 and HL106009 (W.B.); American Heart Association grant 0830213N (B.P.); and the European Hematology Association and the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (Joint Fellowship) (L.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: L.S., F.Y., and B.G.P. designed and performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the paper; A.K.S. performed experiments and edited the paper; K.S., R.P., and D.S.P. performed experiments; W.B. designed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the paper; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Brian G. Petrich, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Dr, Dept 0726, La Jolla, CA 92093-0726; e-mail: bpetrich@ucsd.edu; or Lucia Stefanini, Institute for Cardiovascular and Metabolic Research, University of Reading, School of Biological Sciences, Harborne Bldg, Whiteknights, Reading, RG6 6AS, United Kingdom; e-mail: l.stefanini@reading.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal