In this issue of Blood, Diomede and colleagues establish a novel Caenorhabditis elegans model of primary amyloid cardiotoxicity. Using pharyngeal pumping as a surrogate for cardiac function, they find that human amyloidogenic light-chain proteins directly impair pharyngeal activity. Direct toxicity was associated with the release of reactive oxygen species, and pharyngeal activity was restored with use of antioxidant agents.1

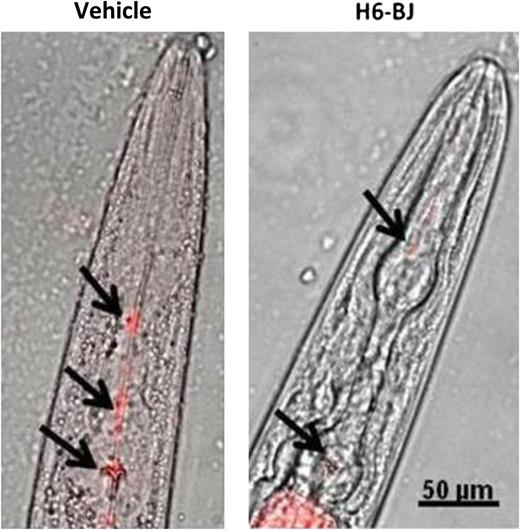

Effects of human amyloidogenic light chain on pharyngeal activity in C elegans. Exposure to human amyloidogenic light chains (H6-BJ, 100 μg/mL) impaired pharyngeal pumping and slowed uptake of fluorescent beads (black arrows). See Figure 1C in the article by Diomede et al that begins on page 3543.

Effects of human amyloidogenic light chain on pharyngeal activity in C elegans. Exposure to human amyloidogenic light chains (H6-BJ, 100 μg/mL) impaired pharyngeal pumping and slowed uptake of fluorescent beads (black arrows). See Figure 1C in the article by Diomede et al that begins on page 3543.

Primary amyloidosis is the most common systemic amyloidosis in the developed world, characterized by the release of amyloidogenic mutant light-chain proteins from plasma cells and systemic deposition in peripheral tissues as proteinaceous β-sheet fibrils.2 Involvement of the heart is associated with the worst prognosis and results in the development of an amyloid cardiomyopathy, often refractory to commonly used heart-failure agents and accompanied by progressive cardiac deterioration and early cardiovascular death.3 Although the origins of systemic amyloidosis dates back to the mid-19th century and the observations of the famed pathologist, Rudolph Virchow, our understanding of this disease process, and in particular amyloid cardiomyopathy, has evolved little since.4 Clinical work has detailed a curious observation with a lack of correlation between the amount of amyloid fibril deposition within the heart and the degree of cardiac dysfunction.5 Furthermore, recent work has identified a direct cardiotoxic response specific for amyloidogenic light-chain proteins isolated from patients with amyloid cardiomyopathy, but not for control, nonamyloidogenic light-chain proteins6 with activation of specific stress-responsive signaling cascades.7 Accelerated understanding of this cardiotoxic response, however, has been limited by the lack of a suitable model organism of disease for study. Although a mouse model has been generated with genetic overexpression of a mutant amyloidogenic light-chain protein, the model fails to replicate the cardiotoxicity or cardiomyopathy that occurs in humans.8 Chronic infusion of human amyloidogenic light-chain proteins has also been attempted in mice, with a subtle cardiotoxic response, but requires use of significant qualities of isolated human light-chain proteins and thereby precludes its application in routine study.7

Diomede and colleagues have now established a unique nematode model of amyloid cardiotoxicity.1 Although nematodes do not have a traditional heart organ, they do have a pharyngeal muscle that resembles the vertebrate heart. The pharynx of C elegans and the vertebrate heart are both tube-like structures, composed of binucleate muscle cells, with continuous, autonomous rhythmic pumping under neurohormonal regulation. Although human cardiomyopathy has previously been modeled in C elegans, this typically has involved study of body-wall muscle cells.9 The authors cleverly reasoned that the pharynx in C elegans, given its close association to vertebrate heart muscle, may similarly exhibit a toxic response to amyloidogenic light-chain proteins. Indeed, the authors found that amyloidogenic light-chain proteins isolated from patients with cardiac involvement resulted in impaired pharyngeal pumping, whereas pharyngeal activity was not altered by amyloidogenic light-chain proteins isolated from patients with predominately renal involvement or with nonamyloidogenic light-chain proteins (see figure). Moreover, this impairment of muscle function was dose dependent over a range of light-chain protein concentrations typically observed in patients with systemic amyloidosis and was unrelated to light-chain oligomerization, secondary structure, stability, or surface hydrophobicity, providing further support for a direct cardiotoxic effect of light-chain proteins. Similar to what has been observed in primary cardiomyocytes exposed to human amyloidogenic light-chain proteins,10 increased oxidant stress was noted in C elegans in this study, with increased reactive radicals, and localized to the mitochondria using redox-sensitive dyes. Of translational significance, antioxidant agents known to quell reactive oxygen species, and currently under phase 2 investigation in patients with primary amyloidosis, protected against pharyngeal dysfunction.

The scientific and translational implications of this paper cannot be overstated. For one, the work presented by Diomede and colleagues1 confirms prior observations made both in vitro in isolated cardiac muscle cells and in vivo in zebrafish, supporting a proposed direct cardiotoxicity specifically with human amyloidogenic light-chain proteins isolated from patients with underlying cardiac involvement.6,7,10 Moreover, the genetic tractability of C elegans and amenability to high-throughput screening using either RNA interference or pharmacologic agents will now allow for systematic investigation of the underlying molecular mechanisms dictating amyloid light-chain–induced cardiotoxicity and potential small-molecule therapies. In addition, given the exceedingly poor prognosis associated with primary amyloidosis once it involves the heart, the C elegans model system described here1 may potentially be used as a bioassay to screen light-chain proteins isolated from patients early in the disease state and prior to overt cardiac dysfunction, allowing for early intervention. Finally, screening of light-chain proteins from large cohorts of patients using the C elegans model system may finally provide some critical insight into the intrinsic light-chain properties that dictate organ specificity, a key unanswered question. This novel C elegans disease model of amyloid cardiotoxicity will enable whole new areas of study and represents a major step forward in the understanding and treatment of systemic amyloidosis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal