Abstract

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is an aggressive lymphoma commonly associated with HIV infection. However, PBL can also be seen in patients with other immunodeficiencies as well as in immunocompetent individuals. Because of its distinct clinical and pathological features, such as lack of expression of CD20, plasmablastic morphology, and clinical course characterized by early relapses and subsequent chemotherapy resistance, PBL can represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for pathologists and clinicians alike. Despite the recent advances in the therapy of HIV-associated and aggressive lymphomas, patients with PBL for the most part have poor outcomes. The objectives of this review are to summarize the current knowledge on the epidemiology, biology, clinical and pathological characteristics, differential diagnosis, therapy, prognostic factors, outcomes, and potential novel therapeutic approaches in patients with PBL and also to increase the awareness toward PBL in the medical community.

Introduction

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a clinicopathological entity that was initially described in 19971 and is now considered a distinct subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) seen more commonly in patients with HIV infection.2 In the original report by Delecluse and colleagues,1 15 of 16 patients were infected with HIV, 1 was an elderly patient, and all the patients had involvement of the oral cavity. In the last decade, several case reports and case series have been published on PBL among HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals.3-7 However, no prospective studies have been undertaken.

The diagnosis of PBL is challenging because it has features that overlap with those of myeloma and with lymphomas that have plasmablastic morphology. This complexity reveals that PBL cannot be readily classified as a B-cell lymphoma or a plasma-cell neoplasm. The challenge of diagnosing this disease is compounded by its aggressive, relapsing clinical course, which poses management and therapeutic challenges, and also by high rates of disease progression and fatality despite the use of state-of-the-art treatment modalities.8 Given its rarity, no standard of care has been established for PBL. However, with a better understanding of the biology of PBL, there is promise for improved outcomes.

In this article, we added to our experience in diagnosing and managing patients with PBL by performing a comprehensive review of the literature that included epidemiologic information, pathogenesis, clinical and pathologic features, prognostic factors, outcomes, and emerging therapeutic options for patients with PBL.

Methods

To provide the most detailed background information on PBL, we conducted an extensive literature search by looking for articles in any language using PubMed/Medline, EMBASE, and Google Scholar published from January 1997 through October 2014. The main search terms used were “plasmablastic lymphoma” and “PBL.” Each article was acquired in full, and reference articles were examined in an effort to eliminate previously included cases. Our search included all cases of PBL diagnosed according to the World Health Organization classification and with relevant clinicopathological information. We excluded reviews and laboratory experiments without original cases, unpublished abstracts, and cases associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) or large B-cell lymphoma arising in HHV-8-associated multicentric Castleman disease (MCD).

Our initial search rendered 612 articles. The number of PBL publications has increased in recent years, which could be a reflection of an increasing awareness of PBL among clinicians and pathologists. In effect, 320 articles were published between 1997 and 2009 (13 years), and 292 articles have been published since 2010 (<5 years). After reviewing the full-text articles, 177 were selected, and data from 590 individual cases of PBL were collected and analyzed.

Epidemiology

The incidence of HIV-associated PBL has been estimated at approximately 2% of all HIV-related lymphomas.9 In addition to a strong association with HIV infection,1,3 PBL has also been reported in patients with other causes of immunodeficiency such as iatrogenic immunosuppression in the context of solid organ transplantation or in elderly patients.4,10 Cases of HIV-negative PBL may also arise from previously existing lymphoproliferative or autoimmune disorders.4,11 A number of cases have been described in otherwise immunocompetent patients.11 However, the actual incidence of both HIV-positive and HIV-negative PBL is unknown.

On the basis of our review of 590 cases, PBL has been reported in patients of all ages (range, age 1 to 90 years), although with only a minority of pediatric cases described to date. The sex distribution in PBL cases shows a male predominance (75%).

Pathogenesis and cell of origin

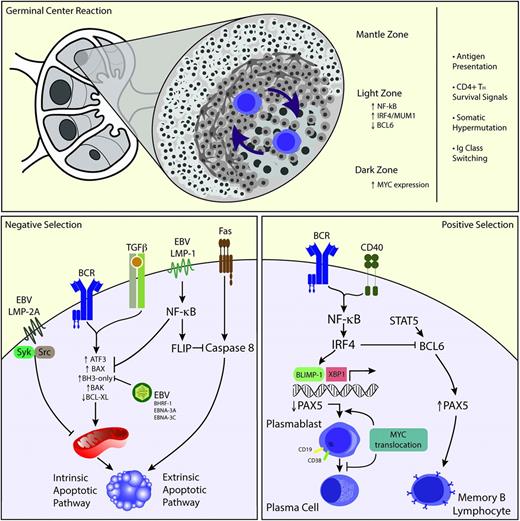

One of the most important functions of the germinal center (GC) reaction is to produce clones of B cells with the highest affinity against a specific antigen.12 Within the GC, B-cell clones migrate from the “light zone” to the “dark zone” and vice versa, outcompeting each other not only for the limited amounts of antigen presented by follicular dendritic cells but also for survival signals from helper T-cells (Figure 1, upper panel). B-cell clones acquire somatic mutations (ie, somatic hypermutation) as a mechanism of affinity maturation.13 In addition, B-cell clones undergo DNA class switching recombination to immunoglobulin A (IgA), IgE, or IgG, increasing antibody diversity. Autoimmune or anergic B-cell clones are deemed to undergo apoptosis.

Proposed biology of PBL. The GC reaction occurs in the primary follicle. Naïve B cells gain exposure to antigen, and B-cell clones undergo selection by alternating between the dark and light zones of the GC (upper panel). EBV infection could play a role in preventing apoptosis via several mechanisms such as induction of NF-κB, through Syk/Src mediation, and induction of BAX/BAK (left lower panel). Conversely, MYC translocations could allow B cells to escape the inhibitory influence of BLIMP-1 favoring plasmablast development but then inhibiting further plasmacytic differentiation by downregulating PAX5 (right lower panel). TH, T helper cell.

Proposed biology of PBL. The GC reaction occurs in the primary follicle. Naïve B cells gain exposure to antigen, and B-cell clones undergo selection by alternating between the dark and light zones of the GC (upper panel). EBV infection could play a role in preventing apoptosis via several mechanisms such as induction of NF-κB, through Syk/Src mediation, and induction of BAX/BAK (left lower panel). Conversely, MYC translocations could allow B cells to escape the inhibitory influence of BLIMP-1 favoring plasmablast development but then inhibiting further plasmacytic differentiation by downregulating PAX5 (right lower panel). TH, T helper cell.

As expected, a large proportion of B cells will undergo apoptosis during the GC reaction. Apoptosis in the GC can be triggered by B-cell receptor (BCR), T-cell growth factor β (TGF-β), or Fas-mediated processes.14 Both BCR and TGF-β signaling induce apoptosis via activation of proapoptotic members of the BCL-2 family resulting in an increase in BH3-only proteins and loss of BCL-XL, which leads to mitochondrial depolarization and intrinsic apoptosis. Rarely, GC B cells undergo apoptosis via FAS. The FAS death induction signaling complex is naturally inactive but gets activated by the lack of survival signaling from T cells and follicular dendritic cells, inducing activation of caspase 8 with subsequent extrinsic apoptosis. The fate of selected GC B lymphocytes is long-lived memory lymphocytes or plasma cells.13 A subset of lymphocytes become plasma cells through stochastic mechanisms, without the need for antigenic stimulation.13 Signaling that leads to plasma cell differentiation involves inactivation of PAX-5 and BCL-6 transcription factors through the plasma cell transcription factor BLIMP-1. Morphologically, centrocytes transform to plasmablasts before becoming mature plasma cells, and phenotypically, cells express CD38, interferon regulatory factor 4/multiple myeloma 1 (IRF-4/MUM-1), and lose CD20 while maintaining CD19 expression.

The cell of origin in PBL is thought to be the plasmablast, an activated B cell that has undergone somatic hypermutation and class switching recombination and is in the process of becoming a plasma cell.2 The presence of plasmablasts is noted in reactive processes associated with viral infections such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and HIV among others. The pathogenesis of PBL is incompletely understood; however, recent studies have identified the presence of MYC gene rearrangements in addition to the association with EBV infection as important pathogenic mechanisms.

PBL is associated with EBV infection, and EBV infection is associated with prevention of apoptosis in B cells by several mechanisms related to EBV antigens (Figure 1, left lower panel). LMP-1, which mimics constitutively active CD40 and provides the necessary T-cell–like survival help, signals through nuclear factor κB (NF-kB) inducing the expression of FLIP and protects B cells from FAS-mediated apoptosis.15 LMP-2A mimics the function of the BCR by associating with Syk and Src, protecting infected B cells from BCR-mediated apoptosis.16 Preventing apoptosis through modulation of the TGF-β pathways is a multilevel endeavor during EBV infection. LMP-1 suppresses the induction of ATF3, a transcription factor associated with TGF-β, and inhibits BAX activity by inducing NF-κB activity.17 EBV produces BHRF-1, a viral BCL-2 homolog, which binds to BAK and the BH3-only proteins PUMA, BID, and BIM. By targeting these BAX/BAK activators, BHRF-1 prevents TGF-β–mediated apoptosis.18 EBNA-3A and EBNA-3C not only regulate BIM protein levels at a transcriptional level but may also prevent MYC-induced apoptosis.19

MYC is the oncogene more commonly dysregulated in human cancer20 and was initially described in Burkitt lymphoma, where it partners with the Ig heavy chain gene. MYC gene rearrangements involving the κ and λ light chain genes and other non-Ig genes have also been described. MYC dysregulation, however, is not sufficient to cause lymphoma, because low levels of t(8;14)(q24;q32) have been detected in healthy individuals by using highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction.21 MYC is a transcription factor that regulates cell proliferation, cell growth, DNA replication, cell metabolism, and cell survival and acts as an activator (amplifier) of the transcribed genes associated with these processes.22 MYC is expressed in B cells initiating the GC reaction at the dark zone of the GC and in a subset of B cells in the light zone of the GC. The activated B cells in the light zone have upregulated NF-κB, and a subset expresses IRF-4/MUM-1 but loses BCL-6. These cells are considered precursors of plasmablasts with the subsequent induction of BLIMP-1. BCL-6 is a repressor of MYC in the GC B cells, whereas BLIMP-1 is a repressor of MYC in terminally differentiated B cells. However, in PBL, MYC dysregulation mediated by translocation or amplification allows MYC to overcome the regulatory effects of BCL-6 or BLIMP-1 (Figure 1, right lower panel). A less well-understood function of MYC is the induction of apoptosis.23 MYC translocations may allow PBL cells to escape apoptosis. Along with the cell cycle dysregulation induced by MYC translocations, the impairment of the DNA damage response, through loss of p53,24 may also play a critical role in the pathogenesis of plasmablastic transformation of low-grade B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders.25

Clinical features

Patients were categorized on the basis of their immunologic status as follows: HIV-positive PBL (n = 369; 63%), HIV-negative PBL (n = 164; 28%), posttransplant PBL (n = 37; 6%), and transformed PBL (n = 20; 3%). Selected clinical features according to immunologic status are shown in Table 1.

Most common sites of involvement in PBL (literature review from 1997 to 2014)

| Sites of involvement . | Total Cases . | HIV-positive . | HIV-negative . | Posttransplant . | Transformed . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | % . | No. . | % . | No. . | % . | No. . | % . | No. . | % . | |

| Oral | 260 | 44 | 178 | 48 | 65 | 40 | 6 | 16 | 11 | 55 |

| Gastrointestinal | 83 | 14 | 43 | 12 | 34 | 21 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 15 |

| Lymph nodes | 43 | 7 | 17 | 5 | 14 | 9 | 11 | 30 | 1 | 5 |

| Skin | 41 | 7 | 22 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 22 | 1 | 5 |

| Bone | 26 | 4 | 19 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Genitourinary | 23 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 15 |

| Nose | 18 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Central nervous system | 17 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Liver | 11 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Lung | 11 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Orbit | 10 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | — | — | ||

| Spleen | 5 | 0.8 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | ||

| Skull | 5 | 0.8 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | ||

| Retroperitoneum | 4 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 2 | — | — | ||

| Breast | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Larynx | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 | — | — | — | |||

| Gallbladder | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 | — | — | — | |||

| Choroid | 1 | 0.1 | — | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | |||

| Heart | 1 | 0.1 | — | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | |||

| Parotid | 1 | 0.1 | — | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | |||

| Muscle | 1 | 0.1 | — | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | |||

| Not specified | 22 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 4 | — | — | ||

| Total | 590 | 369 | 164 | 37 | 20 | |||||

| Sites of involvement . | Total Cases . | HIV-positive . | HIV-negative . | Posttransplant . | Transformed . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | % . | No. . | % . | No. . | % . | No. . | % . | No. . | % . | |

| Oral | 260 | 44 | 178 | 48 | 65 | 40 | 6 | 16 | 11 | 55 |

| Gastrointestinal | 83 | 14 | 43 | 12 | 34 | 21 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 15 |

| Lymph nodes | 43 | 7 | 17 | 5 | 14 | 9 | 11 | 30 | 1 | 5 |

| Skin | 41 | 7 | 22 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 22 | 1 | 5 |

| Bone | 26 | 4 | 19 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Genitourinary | 23 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 15 |

| Nose | 18 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Central nervous system | 17 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Liver | 11 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Lung | 11 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Orbit | 10 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | — | — | ||

| Spleen | 5 | 0.8 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | ||

| Skull | 5 | 0.8 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | ||

| Retroperitoneum | 4 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 2 | — | — | ||

| Breast | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 3 | — | |

| Larynx | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 | — | — | — | |||

| Gallbladder | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 | — | — | — | |||

| Choroid | 1 | 0.1 | — | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | |||

| Heart | 1 | 0.1 | — | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | |||

| Parotid | 1 | 0.1 | — | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | |||

| Muscle | 1 | 0.1 | — | 1 | 0.6 | — | — | |||

| Not specified | 22 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 4 | — | — | ||

| Total | 590 | 369 | 164 | 37 | 20 | |||||

HIV-positive PBL

Of the 369 HIV-positive patients with PBL, 286 (78%) were male with a median age at presentation of 42 years (range, 1 to 80 years). Extranodal presentation was the most frequent (95% of patients), 48% of which involved oral cavity/jaw, 12% gastrointestinal tract, and 6% skin. PBL was the initial presentation of HIV infection in approximately 7% of the patients. More than 65% of patients presented with advanced clinical stage (ie, PBL stage III or IV). Furthermore, bone marrow involvement and B symptoms occurred in almost 40% of HIV-positive individuals.

HIV-negative PBL

HIV-negative PBL affects a relatively higher proportion of female patients (34%) in contrast to HIV-positive PBL and occurs in older patients with a median age at presentation of 55 years. Although oral involvement is common (40%), PBL in immunocompetent individuals seems to be more heterogeneous in terms of sites of involvement. Advanced clinical stage, B symptoms, and bone marrow involvement are relatively less common (25%) than in HIV-positive patients with PBL.

Posttransplant PBL

We identified 37 cases of PBL in transplant recipients, 28 (76%) were men with a median age at presentation of 62 years. From these cases, 38% were seen after heart, 27% after kidney, 14% after hematopoietic stem cell, 11% after lung, 8% after liver, and 3% after pancreas transplant. Interestingly, lymph nodes were a common site of involvement (30%), followed by skin (22%). Advanced clinical stage has been reported in about 50% of patients with posttransplant PBL.

Transformed PBL

Twenty patients in whom PBL evolved from another hematologic disease were identified in the literature, of which 18 (90%) were male with a median age at presentation of 62 years. Ten (50%) evolved from chronic lymphocytic leukemia and 6 (30%) from follicular lymphoma.

Pediatric cases

PBL was reported in 21 pediatric cases, of which 18 were male (85%) with a median age at presentation of 10 years (range, 1 to 17 years). Eighteen cases were HIV-positive and 3 were HIV-negative. More than 80% of pediatric PBL cases presented with advanced stage. The oral cavity (33%) was the most common site of involvement.

Pathological features

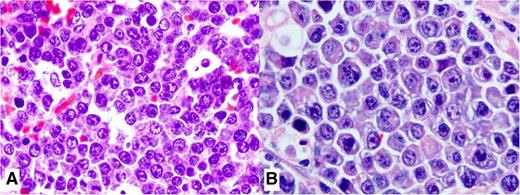

PBL is a high-grade neoplasm with cytomorphologic features such as large immunoblasts or large plasma cells that express plasma cell markers and lack B-cell markers.2 The diagnosis can be challenging because the tumor cells may be indistinguishable from plasmablastic myeloma or from lymphomas with plasmablastic morphology. The tumor has a diffuse growth pattern, and it effaces the architecture of extranodal or nodal sites. A “starry-sky” pattern, with frequent tingible body macrophages is common. The neoplastic cells are large with abundant cytoplasm and central oval vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli as noted in large immunoblasts. When PBL occurs in the oral mucosa of HIV-positive patients, the neoplastic cells appear as large centroblasts and/or immunoblasts (Figure 2A), whereas a more apparent plasma cell differentiation with basophilic cytoplasm, paranuclear hof, and eccentric large nuclei (Figure 2B) occurs more in extranodal sites different from the oral mucosa in HIV-negative patients. Necrosis, karyorrhexis, and increased mitotic figures are common.26

Histopathologic features of PBL. (A) This high magnification shows the cytologic features of a case of PBL in an HIV-positive patient. It displays large cells with an immunoblastic appearance, with central oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli and moderately abundant cytoplasm. (B) Cytologic features of a case of PBL in an HIV-negative patient with extranodal involvement away from the oral mucosa show plasmacytic plasmablasts with abundant bluish cytoplasm, paranuclear hof, and large nuclei. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification, ×1000).

Histopathologic features of PBL. (A) This high magnification shows the cytologic features of a case of PBL in an HIV-positive patient. It displays large cells with an immunoblastic appearance, with central oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli and moderately abundant cytoplasm. (B) Cytologic features of a case of PBL in an HIV-negative patient with extranodal involvement away from the oral mucosa show plasmacytic plasmablasts with abundant bluish cytoplasm, paranuclear hof, and large nuclei. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification, ×1000).

The immunophenotype is similar to that in plasma cell neoplasms, positive for CD79a, IRF-4/MUM-1, BLIMP-1, CD38, and CD138.26 The neoplastic cells are negative for B-cell markers CD19, CD20, and PAX-5; however, a subset may be dim positive for CD45. Some cases express T-cell markers CD2 or CD4.5 Immunohistochemistry with the antibody MIB-1, which detects the proliferation marker Ki-67, shows that most or all neoplastic cells are positive. MYC is expressed in about 50% of cases and correlates with MYC translocations or amplification. About 70% of cases express EBV-encoded RNA (EBER), which is the most sensitive methodology for detecting EBV infection within the malignant cells. In a recent study, EBV infection based on EBER expression was more commonly seen in HIV-positive patients (75%) and in patients with PBL arising in the posttransplant setting (67%) than in immunocompetent patients (50%).5 EBV LMP-1 is usually negative in most studies, and the latency pattern type I is most common; however, latency pattern type III can be observed in patients with HIV infection and in those patients with posttransplant PBL. Additional pathological details and a representative profile of a patient with PBL are shown in Table 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

Selected pathological features of PBL (literature review from 1997 to 2014)

| Feature . | All cases . | HIV-positive . | HIV-negative . | Posttransplant . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunophenotype | ||||

| CD10 | 20% | 32% | 15% | 0% |

| CD20 | Low | 8% | 3% | 3% |

| CD30 | Subset | |||

| CD45 | Low | 31% | 33% | 70% |

| CD56 | 25% | 27% | 22% | 42% |

| CD79a | Common | 45% | 36% | 68% |

| CD138 | 90% | 94% | 87% | 88% |

| ALK-1 | 0% | |||

| BCL-2 | Uncommon | |||

| BCL-6 | Negative | |||

| EMA | Common | |||

| HHV-8 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| IRF-4/MUM-1 | ∼100% | ∼100% | ∼100% | 100% |

| EBV LMP-1 | Uncommon | Occasional | Occasional | |

| EBNA-2 | Negative | |||

| EBV latency pattern | Type I | Type I or III | Type I | Type III |

| Cytoplasm Ig | Common | |||

| MIB-1/Ki-67 | High | 90% | 83% | 88% |

| PAX-5 | Negative | |||

| MYC | ∼50% | |||

| TP53 | ∼50% | 67% | 8% | |

| Molecular testing | ||||

| BCL-2 GR | Negative | |||

| BCL-6 GR | Negative | |||

| EBER | 66% | 75% | 50% | 67% |

| IgH GR | Monoclonal | |||

| MYC GR/amplifications | 57% | 78% | 44% | 38% |

| TCR GR | Polyclonal | |||

| Gene profile | Segmental gains: 1p35.1-1p36.12, 1q21.1-1q23.1, 1p36.11-1p36.33 | DNMT3B, PTP4A3, CD320 |

| Feature . | All cases . | HIV-positive . | HIV-negative . | Posttransplant . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunophenotype | ||||

| CD10 | 20% | 32% | 15% | 0% |

| CD20 | Low | 8% | 3% | 3% |

| CD30 | Subset | |||

| CD45 | Low | 31% | 33% | 70% |

| CD56 | 25% | 27% | 22% | 42% |

| CD79a | Common | 45% | 36% | 68% |

| CD138 | 90% | 94% | 87% | 88% |

| ALK-1 | 0% | |||

| BCL-2 | Uncommon | |||

| BCL-6 | Negative | |||

| EMA | Common | |||

| HHV-8 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| IRF-4/MUM-1 | ∼100% | ∼100% | ∼100% | 100% |

| EBV LMP-1 | Uncommon | Occasional | Occasional | |

| EBNA-2 | Negative | |||

| EBV latency pattern | Type I | Type I or III | Type I | Type III |

| Cytoplasm Ig | Common | |||

| MIB-1/Ki-67 | High | 90% | 83% | 88% |

| PAX-5 | Negative | |||

| MYC | ∼50% | |||

| TP53 | ∼50% | 67% | 8% | |

| Molecular testing | ||||

| BCL-2 GR | Negative | |||

| BCL-6 GR | Negative | |||

| EBER | 66% | 75% | 50% | 67% |

| IgH GR | Monoclonal | |||

| MYC GR/amplifications | 57% | 78% | 44% | 38% |

| TCR GR | Polyclonal | |||

| Gene profile | Segmental gains: 1p35.1-1p36.12, 1q21.1-1q23.1, 1p36.11-1p36.33 | DNMT3B, PTP4A3, CD320 |

ALK-1, anaplastic lymphoma kinase 1; EBNA-2, EBV nuclear antigen 2; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen; GR, gene rearrangement; IRF-4/MUM-1, interferon regulatory factor 4/multiple myeloma 1; LMP-1, latent membrane protein 1; TCR, T-cell receptor.

Immunophenotype of PBL. Immunohistochemistry with hematoxylin counterstain shows lack of expression of CD20 and CD10 and positive expression of IRF4/MUM1, Ki67, and MYC (magnification, ×400). Detection of EBER by in situ hybridization shows that neoplastic cells are positive; nuclear reactivity (×400).

Immunophenotype of PBL. Immunohistochemistry with hematoxylin counterstain shows lack of expression of CD20 and CD10 and positive expression of IRF4/MUM1, Ki67, and MYC (magnification, ×400). Detection of EBER by in situ hybridization shows that neoplastic cells are positive; nuclear reactivity (×400).

Differential diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis of PBL is plasmablastic or anaplastic multiple myeloma that may be morphologically and immunophenotypically identical to PBL.26 Features that favor PBL include association with HIV infection and EBER positivity in neoplastic cells. Features favoring myeloma include the presence of monoclonal paraproteinemia, hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, and lytic bone lesions. However, the distinction may be impossible and is clearly arbitrary in rare cases. The median age of PBL patients without underlying immunodeficiency is 64 years,5 which coupled with their frequent association with EBV infection, overlaps with EBV-positive DLBCL of the elderly, which is usually CD20+.30,31 Primary effusion lymphoma usually manifests as pleural or pericardial effusion and rarely associates with lymphadenopathy or mass, but it shows a strong association with HHV-8.32 Plasmablastic microlymphoma arising in MCD can be distinguished by recognizing underlying MCD, IgA or IgG λ light chain restriction and strong association with HHV-8.33 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive DLBCL is considered to arise from unmutated IgM-expressing B cells and shows plasmablasts that express CD138 and IRF-4/MUM-1 and lack PAX-5 and CD20.34,35 The expression of ALK usually results from t(2;17)(p23;q23) in which ALK partners with CLTC. DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation is associated with EBV infection and usually involves body cavities or narrow spaces.36 The latency period between chronic inflammation and the development of the lymphoma is more than 10 years. Localized tumors associated with medical devices or associated with cardiac myxomas are included in this category.37 Selected details on the differential diagnosis of PBL are shown in Table 3.

Differential diagnosis of PBL

| . | PBL . | Plasmablastic myeloma . | LBCL HHV-8–positive . | IBL DLBLC . | ALK-positive DLBCL . | DLBCL ACI . | PEL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease distribution | Extranodal | Bone marrow and extranodal | Nodal | Nodal | Nodal | Extranodal | Extranodal |

| HIV infection | ∼70% | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Pathogenesis | EBV, HIV, IL-10 | IL-6 | HHV-8, MCD | ALK | EBV, IL-10, IL-6 | HHV-8 | |

| Positive markers | CD138, IRF-4/MUM-1, MYC | CD138, cytoplasmic Ig, MYC | CD20−/+, CD138+/−, IgM | CD20, PAX-5, | ALK, CD4, CD45 | CD20, CD4 | IRF-4/MUM-1, CD30−/+ |

| Negative markers | CD20, PAX-5 | CD20, PAX-5, BCL-6 | CD138 | CD4, CD138 | CD20, CD30, MYC | ALK | PAX-5, CD20, CD138, Ig |

| Proliferation rate | >90% | >90% | >90% | ∼80% | >90% | >90% | >90% |

| Cytoplasmic immunoglobulin | 50%-70% | >90% | IgA λ | Uncommon | Uncommon | Uncommon | Uncommon |

| EBV infection | Common | No | No | No | No | Common | Common |

| EBV latency pattern | I | NA | NA | NA | NA | III | I |

| HHV-8 infection | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Molecular genetics | MYC GR | Myeloma FISH abnormalities | Unmutated Ig | MYC GR | t(2;17)(p23;q23) | TP53 mutations | Hypermutated Is |

| . | PBL . | Plasmablastic myeloma . | LBCL HHV-8–positive . | IBL DLBLC . | ALK-positive DLBCL . | DLBCL ACI . | PEL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease distribution | Extranodal | Bone marrow and extranodal | Nodal | Nodal | Nodal | Extranodal | Extranodal |

| HIV infection | ∼70% | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Pathogenesis | EBV, HIV, IL-10 | IL-6 | HHV-8, MCD | ALK | EBV, IL-10, IL-6 | HHV-8 | |

| Positive markers | CD138, IRF-4/MUM-1, MYC | CD138, cytoplasmic Ig, MYC | CD20−/+, CD138+/−, IgM | CD20, PAX-5, | ALK, CD4, CD45 | CD20, CD4 | IRF-4/MUM-1, CD30−/+ |

| Negative markers | CD20, PAX-5 | CD20, PAX-5, BCL-6 | CD138 | CD4, CD138 | CD20, CD30, MYC | ALK | PAX-5, CD20, CD138, Ig |

| Proliferation rate | >90% | >90% | >90% | ∼80% | >90% | >90% | >90% |

| Cytoplasmic immunoglobulin | 50%-70% | >90% | IgA λ | Uncommon | Uncommon | Uncommon | Uncommon |

| EBV infection | Common | No | No | No | No | Common | Common |

| EBV latency pattern | I | NA | NA | NA | NA | III | I |

| HHV-8 infection | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Molecular genetics | MYC GR | Myeloma FISH abnormalities | Unmutated Ig | MYC GR | t(2;17)(p23;q23) | TP53 mutations | Hypermutated Is |

ACI, associated with chronic inflammation; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; GR, gene rearrangement; IBL, immunoblastic; IL, interleukin; IRF-4/MUM-1, interferon regulatory factor 4/multiple myeloma 1; LBCL, large B-cell lymphoma; NA, not available; PEL, primary effusion lymphoma.

Survival and prognostic factors

The prognosis of patients with PBL is poor. A systematic review of 112 HIV-positive patients with PBL showed a median overall survival (OS) of 15 months and a 3-year OS rate of 25%.38 Similarly, a systematic review of 76 HIV-negative PBL patients showed a median OS of 9 months with a 2-year OS rate of 10%.39 A more recent systematic review of approximately 300 patients with PBL showed a median OS of 8 months. The median OS in HIV-positive patients was 10 months, 11 months in HIV-negative immunocompetent, and 7 months in posttransplant PBL patients.5

Similar poor outcomes were seen among 50 HIV-positive PBL patients who received combined antiretroviral therapy (cART). This was a multicenter, retrospective case series from 13 institutions that reported a median OS of 11 months and a 5-year OS rate of 24%.3 A German study from 30 centers that included 18 HIV-positive patients with PBL treated after 2005 reported a median OS of 5 months.6 The AIDS Malignancy Consortium presented data in abstract form from 9 centers that included 19 HIV-positive patients treated after 1999; the 1-year OS rate was 67%.40 Although encouraging, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions given the preliminary nature of the report. An Italian study showed 3-year OS of 67% in 13 HIV-positive PBL patients treated with cART.41 The reasons for the better outcome are unclear, although the patients had a CD4+ count >0.2 × 109/L. Comparative studies showed that HIV status did not appear to affect outcomes in PBL.5,42 However, there was a suggestion that immunosuppression among HIV-negative patients was associated with worse outcomes.10

The International Prognostic Index (IPI) scoring system is the most commonly used risk stratification tool for aggressive lymphomas, and it includes age, performance status, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, number of extranodal sites, and clinical stage to prognosticate survival.43 A series of retrospective studies have shown that the IPI score has prognostic value in patients with PBL.3,6,41 However, the prognostic value of the IPI score in PBL appears to heavily rely on advanced stage and poor performance status as indicators of worse outcome.3,6,44 Age, LDH levels, and bone marrow involvement did not appear to affect outcomes in a retrospective case series3 ; however, age and LDH levels were associated with adverse outcomes in another study.6

The prognostic value of EBV-related antigens expression in PBL cases is unclear. Some studies have shown that EBV expression is not associated with outcome in HIV-associated PBL.6,42,44 However, other studies have associated EBV with a better outcome in immunocompetent patients with PBL. Of note, EBV expression is commonly determined by the expression of EBER in the malignant cells. EBER is not a quantitative test, however, and does not allow stratifying subsets of infection. More recently, the presence of MYC gene rearrangements has been shown to be associated with shorter OS time in patients with PBL. In a systematic review that assessed 57 patients with PBL in whom MYC status was evaluated, patients with MYC gains or translocations had a worse OS than patients with a normal MYC.5 Specifically in HIV-positive patients with PBL, MYC gene rearrangements were associated with a sixfold increased risk of dying from any cause.3

The expression of CD20 or CD45 has not been associated with outcomes in patients with PBL.39,42,44 Conversely, a series of studies have suggested a worse outcome in patients with Ki-67 expression >80%.3,39,42,44 A smaller study did not show prognostic value for Ki-67 expression.6 In HIV-associated PBL, CD4+ counts <0.2 × 109/L were not associated with worse OS3,41 but appeared to associate with shorter progression-free survival time.3,6

Current treatment options and emerging therapies

The outcome of untreated patients with PBL is dismal, with a median OS of 3 months for HIV-positive patients and 4 months for HIV-negative patients.42 Conversely, HIV-positive patients with PBL who attain a complete remission after chemotherapy achieve better outcomes.3,44 Spontaneous regression of PBL after initiation of cART was noted in two case reports of HIV-positive patients.45,46 Similarly, regression of PBL after decreasing dose of methotrexate was noted in an HIV-negative patient with rheumatoid arthritis.47

Given the dismal prognosis of patients with PBL, we can argue that there is no standard of care for patients with PBL. In particular, the use of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) is considered inadequate therapy, and current guidelines recommend more intensive regimens.48 Such regimens include infusional etoposide, vincristine and doxorubicin with bolus cyclophosphamide and prednisone (EPOCH),49 cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, methotrexate alternating with ifosfamide, etoposide, and cytarabine (CODOX-M/IVAC),50 or hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine (hyper-CVAD).51 However, two studies of patients with PBL treated with chemotherapy regimens more intensive than CHOP did not identify a survival benefit.3,44 A patient-level meta-analysis identified a survival benefit of using EPOCH over CHOP in patients with HIV-associated lymphomas.52,53 It is unclear, however, whether any patients with PBL were included in this analysis. Importantly, two prospective studies are evaluating the safety and efficacy of infusional EPOCH in patients with high-risk DLBCL, including PBL (NCT01092182 and CTSU-9177).

Only a handful of cases have reported the use of intrathecal agents to minimize the risk of central nervous system involvement. However, given the high proliferation rate of PBL, the strong association with HIV infection, the high rate of extranodal involvement, and the presence of MYC translocations, we believe that intrathecal prophylaxis should be considered in most patients with PBL. The improved outcomes of cART among patients with HIV-associated DLBCL have not been readily apparent among patients with HIV-associated PBL. Two studies suggested that HIV-positive patients with PBL who also received cART had improved survival,41,44 whereas another study did not.3 The information on radiotherapy is rather scant. Radiotherapy has been used as part of treatment in approximately 20 to 30 PBL cases from the literature, but no conclusion can be made from this limited experience. More recently, the role of stem cell transplantation (SCT) in patients with PBL has been assessed.54 It appears that patients with PBL with chemotherapy-sensitive disease might benefit from autologous SCT in first remission. An Italian study reported that 5 HIV-positive patients with PBL who received high-dose chemotherapy (HDC) followed by autologous SCT in first remission achieved prolonged OS times.41 Similarly, a case series of 9 HIV-negative patients with PBL reported encouraging results with a 5-year OS rate of 60%.10 In that study, 4 patients underwent HDC followed by autologous SCT in first remission. The experience with HDC followed by autologous SCT in the relapsed setting is rather limited, although there is some suggestion that persistent complete remission can be achieved in chemotherapy-sensitive disease.41 The use of allogeneic SCT in HIV-positive PBL showed limited efficacy.54

Given the poor outcomes and survival of patients with PBL, novel agents are needed. The use of antimyeloma agents has been attempted on the basis of the plasmacytic differentiation of PBL cells, although the experience is limited to case reports. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib has been shown to be effective in patients with post-GC DLBCL, inducing higher response and survival rates when used in combination with anthracycline-containing regimens.55 Bortezomib alone and in combination with chemotherapy has been used with limited efficacy in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with relapsed PBL.56-62 More recently, a case series of 3 previously untreated patients with PBL, 2 of them HIV-positive, has shown efficacy with the combination of bortezomib and dose-adjusted EPOCH.63 The immunomodulator lenalidomide induced a temporary response in a patient with relapsed PBL.56 Studies have shown that approximately 30% of PBL cases express the activation marker CD30,4,28,64 and a recent report showed response to brentuximab vedotin in a patient with CD30-expressing relapsed PBL.65 A specific cutoff for CD30 positivity among lymphoma cells, however, has not been defined.

Our recommendation for first-line treatment of PBL is 6 cycles of infusional dose-adjusted EPOCH (with or without bortezomib) with intrathecal prophylaxis with each cycle of EPOCH and consideration of consolidative HDC followed by autologous SCT in first remission for appropriate candidates. In HIV-positive patients, cART should be started or optimized under the supervision of an infectious disease specialist with experience in the potential interactions between anticancer agents and cART. We recommend radiotherapy in the palliative setting, although it can be considered as consolidation in a case-by-case basis after a full course of combination chemotherapy has been administered.

Future directions

Potential therapeutic approaches for patients with PBL could include EBV-directed therapies in the form of antiviral agents or EBV-targeted cellular immunotherapy, and these approaches have not yet been evaluated in patients with PBL. Antiviral agents, such as ganciclovir, have been relatively unsuccessful because of the quiescent nature of the virus outside the lytic phase. Lytic viral activity results in elevation of thymidine kinase levels allowing antivirals to exert their effects through inhibition of viral DNA replication. Arginine butyrate has been shown to upregulate thymidine kinase activity and induce the lytic phase. A phase I/II trial of arginine butyrate with ganciclovir in 15 patients with refractory EBV-positive lymphoid malignancies showed limited activity with the exception of posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders, in which a response rate of 83% was observed.66 A study combining bortezomib and ganciclovir for EBV-associated lymphomas has recently been terminated for undisclosed reasons (NCT00093704). Cellular immunotherapy against EBV has been attempted in the form of EBV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) or chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. There are several limitations for the widespread use of CTLs, including lack of persistence and the long preparation time as well as the specialized facilities needed for their production.67 CAR T cells might be able to overcome some of the drawbacks of regular CTLs. An ongoing study is evaluating the therapeutic value of autologous EBV-specific CAR T cells with CD30 as the target (NCT01192464). Potentially, CAR T cells can be directed against EBV antigens in patients with EBV-associated lymphomas including PBL.

Another potential target of interest is the MYC gene. The MYC gene has been considered untargetable, given its lack of a binding domain.68 MYC heterodimerizes with the transcription factor Max, but the tridimensional structure of this complex does not permit the positioning of small molecules.69 The transcriptional function of MYC can be targeted, however. MYC uses members of the bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) subfamily of bromodomain proteins such as BRD2, BRD3, and BRD4 to amplify signal transduction aimed at regulating cell proliferation, metabolism, and survival.70 MYC dysregulation has also been described in multiple myeloma, and higher expression of BRD4 has been observed in myeloma cells when compared with normal bone marrow plasma cells.71 A recent experiment used JQ1, a selective small molecule bromodomain inhibitor, to assess its effects on MYC transcription.71 JQ1 was able to inhibit MYC transcription characterized by downregulation of MYC-dependent genes. In addition, BET inhibition by JQ1 was associated with cell cycle arrest and cellular senescence in multiple myeloma cell lines and murine models.

Conclusion

PBL remains a hard-to-diagnose and hard-to-treat lymphoma. Recent advances in the therapy of HIV-associated and aggressive lymphomas do not seem to have had a positive impact on the outcome of patients with PBL. Given the rarity and heterogeneity of PBL, it is likely that no large, randomized controlled therapeutic studies would ever be done. From our perspective, multi-institutional collaboration would be an effective mechanism by which diagnostic and therapeutic advances can come to light in rare diseases such as PBL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Kenneth Bishop from the Division of Hematology and Oncology, Rhode Island Hospital, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, RI, for his help with the design of Figure 1.

Authorship

Contribution: J.J.C. designed the review; and J.J.C., M.B., and R.N.M. performed the systematic review, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.J.C. is a consultant for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jorge J. Castillo, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, 450 Brookline Ave, M221, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: jorgej_castillo@dfci.harvard.edu.