Abstract

Priapism is a disorder of persistent penile erection unrelated to sexual interest or desire. This pathologic condition, specifically the ischemic variant, is often associated with devastating complications, notably erectile dysfunction. Because priapism demonstrates high prevalence in patients with hematologic disorders, most commonly sickle cell disease (SCD), there is significant concern for its sequelae in this affected population. Thus, timely diagnosis and management are critical for the prevention or at least reduction of cavernosal tissue ischemia and potential damage consequent to each episode. Current guidelines and management strategies focus primarily on reactive treatments. However, an increasing understanding of the molecular pathophysiology of SCD-associated priapism has led to the identification of new potential therapeutic targets. Future agents are being developed and explored for use in the prevention of priapism.

Introduction

Priapism is an uncommon pathologic condition involving prolonged penile erection in the absence of sexual arousal or desire.1,2 The term is derived from Priapus, a Greek god of fertility renowned for his large phallus.3,4 Incidence rates of 1.5 per 100 000 person-years have been estimated among the general population.5 The ischemic sub-type is common in sickle cell disease (SCD) with prevalence rates of up to 40%.6,7 In fact, SCD is an etiologic factor in approximately 23% of adult and 63% of pediatric cases.8 Several previous cohort studies have demonstrated high prevalence rates ranging from 27.5% to 42% in SCD, with up to 89% estimated to experience priapism by 20 years of age.6,7,9

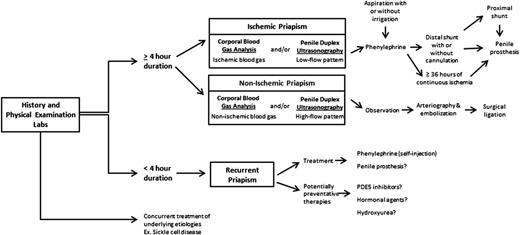

Ischemic priapism is associated with devastating complications including erectile tissue necrosis and fibrosis.1,2 When episodes are unremitting, increasingly invasive options are used in an attempt to prevent worsening tissue damage and preserve erectile function or simply provide palliative care when erectile function can no longer be preserved. Here, we present an algorithm for identifying and managing ischemic priapism in SCD, as well as the rationale behind various treatments.

Case

R. J. was a 22-year-old African American man who presented to the emergency room with a painful erection lasting ∼6 hours. He had been in his usual state of health until he finished mowing the lawn and noticed a gradual development of an erection. He tried over-the-counter analgesics and masturbation without improvement. He reported previous episodes requiring several emergency room visits in the past few months, which resolved spontaneously with supplemental oxygen. There was no penile or pelvic trauma, although he reported a family history of SCD. On examination, he had a tender, engorged phallus. There was no hematoma, mucosal pallor, or scleral icterus; remaining examination was unremarkable. He received supplemental oxygen and morphine for pain. Corporal aspiration and blood-gas analysis were consistent with ischemia. Further corporal aspiration and irrigation were performed without improvement. Phenylephrine injections ultimately led to penile detumescence. Hemoglobin (Hb) variant analysis using high performance liquid chromatography showed Hb sickle cell anemia. He was then monitored overnight and discharged the next day.

Nitric oxide role in normal erection physiology

Penile erection involves a complex coordination of vasorelaxing and vasoconstricting signals from parasympathetic and sympathetic inputs,10 respectively, in order to control blood flow within the penis and allow for its engorgement.11 In its basal state, vascular and smooth muscle tone is maintained by vasoconstrictive factors,10 allowing the penis to remain in a flaccid state for nearly 23 hours each day.12 Inhibition of this contractile state can occur with genital stimulation, psychosexual excitement, or rapid eye movement sleep.13 Upon stimulation, penile erection is facilitated by smooth muscle relaxation, allowing for increased arterial blood flow and trabecular cavernosal tissue distension.14 This distension reduces venous outflow, thus permitting and sustaining penile engorgement.15 Recent investigations into molecular mechanisms underlying penile erection have revealed nitric oxide (NO) signaling as a critical component in normal erections.16,17 Erectile stimulation involves vascular and neurogenic pathways regulated by endothelial and neuronal isoforms of the NO synthase (NOS) enzyme, the primary mediator of NO synthesis. Upon activation, endothelial NOS and neuronal NOS use l-arginine to generate NO, which diffuses locally into smooth muscle cells to initiate vasodilation through activation of the downstream cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway (Figure 1).13,18 Termination of the erectile response occurs when phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) hydrolyzes cGMP, inactivating the second messenger nucleotide19 and returning the penis to its flaccid state (Figure 1).

Schematic representation of the molecular pathophysiologic mechanisms of RIP that has a likely local vasculogenic association. Normal penile erection physiology depicted on top. This schema does not preclude other neurogenic or hormonal factors that may be involved in eliciting priapism. Decreased basal levels of PDE5 enzyme permits uncontrolled erection (priapism) because of the lack of the normal regulatory control mechanism involved in the return of the penis back to its flaccid state. Circular arrows signify the pathway between penile erection states. Horizontal black arrows signify regulation. Horizontal black T-shapes signify inhibition. Downward black arrows signify downregulation.

Schematic representation of the molecular pathophysiologic mechanisms of RIP that has a likely local vasculogenic association. Normal penile erection physiology depicted on top. This schema does not preclude other neurogenic or hormonal factors that may be involved in eliciting priapism. Decreased basal levels of PDE5 enzyme permits uncontrolled erection (priapism) because of the lack of the normal regulatory control mechanism involved in the return of the penis back to its flaccid state. Circular arrows signify the pathway between penile erection states. Horizontal black arrows signify regulation. Horizontal black T-shapes signify inhibition. Downward black arrows signify downregulation.

Priapism classification and etiology

Ischemic priapism

Ischemic priapism, also known as low-flow or veno-occlusive priapism, comprises over 95% of presentations20 and is the variant most commonly observed in patients with SCD. Ischemic priapism is associated with decreased or absent cavernous blood flow, corporal rigidity, and pain.2 It represents a compartment-like syndrome characterized by increased pressure within the enclosed cavernosal space and compressed circulation.21 Consequently, ischemic priapism is a medical emergency with potentially profound sequelae if left untreated. Histopathologic studies show time-dependent erectile tissue damage22 with irreversible corporal damage occurring in episodes lasting ≥6 hours (major priapism).23 Thus, patients are advised to seek immediate medical care with major episodes.2 Beyond 24 hours, tissue necrosis and fibroblast proliferation result22,24 and can lead to erectile dysfunction (ED), with estimated rates as high as 90% from episodes lasting ≥24 hours.20 Priapism can also lead to significant psychological and social sequelae.25

Diverse etiologies for priapism have been described, including neurologic conditions, pharmacologic exposures, trauma, and idiopathic presentations (Table 1). Hematologic disorders, such as SCD, glucose-6-phosphate deficiency, and hereditary spherocytosis, have been implicated in ischemic priapism.7,26,27 Although SCD itself is a key risk factor, the presence of other SCD complications, including ischemic stroke, leg ulcers, and vaso-occlusive episodes, have been associated with priapism.28 To identify SCD patients at risk for priapism, hemolytic biomarkers were investigated, and patients with a history of priapism have significantly lower Hbs and higher lactate dehydrogenase compared with SCD patients without priapism.29,30 Moreover, polymorphisms in genes that regulate vascular tone, endothelial NO metabolism, coagulation, cell adhesion, and cell hydration have been linked to priapism in SCD.31,32 However, parameters are not readily available and further studies are needed to validate these findings.11

Causes of priapism

| Etiology . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| Hematologic disorders | SCD, thalassemia, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| Medications | Vasoactive erectile agents (papaverine, phentolamine, prostaglandin E1, combination therapy), α-adrenergic receptor antagonists (prazosin, terazosin, tamulosin), antianxiety agents (hydroxyzine), anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin), antidepressants and antipsychotics (trazadone, bupropion, fluoxetine, sertraline, lithium, clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, phenothiazines), antihypertensives (hydralazine, guanethidine, propranolol) |

| Recreational drugs | Alcohol, cocaine, marijuana |

| Hormones | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone, testosterone |

| Infectious | Scorpion sting, spider bite, rabies, malaria |

| Metabolic | Amyloidosis, Fabry disease, gout |

| Neoplastic (regional infiltration or metastatic) | Kidney, bladder, prostate, urethra, penis, testis, colorectal, lung |

| Neurogenic | Syphilis, spinal cord injury, cauda equina syndrome, autonomic neuropathy, lumbar disc herniation, spinal stenosis, stroke, brain tumor, spinal anesthesia |

| Anxiety disorders | General anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, panic disorder |

| Anesthesia | General or regional |

| Trauma (nonischemic) | Straddle injury, coital injury, pelvic trauma, intracavernous injection needle injury |

| Iatrogenic (nonischemic) | Penile revascularization surgery, intracavernous needle injury, shunt surgery |

| Etiology . | Examples . |

|---|---|

| Hematologic disorders | SCD, thalassemia, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| Medications | Vasoactive erectile agents (papaverine, phentolamine, prostaglandin E1, combination therapy), α-adrenergic receptor antagonists (prazosin, terazosin, tamulosin), antianxiety agents (hydroxyzine), anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin), antidepressants and antipsychotics (trazadone, bupropion, fluoxetine, sertraline, lithium, clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, phenothiazines), antihypertensives (hydralazine, guanethidine, propranolol) |

| Recreational drugs | Alcohol, cocaine, marijuana |

| Hormones | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone, testosterone |

| Infectious | Scorpion sting, spider bite, rabies, malaria |

| Metabolic | Amyloidosis, Fabry disease, gout |

| Neoplastic (regional infiltration or metastatic) | Kidney, bladder, prostate, urethra, penis, testis, colorectal, lung |

| Neurogenic | Syphilis, spinal cord injury, cauda equina syndrome, autonomic neuropathy, lumbar disc herniation, spinal stenosis, stroke, brain tumor, spinal anesthesia |

| Anxiety disorders | General anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, panic disorder |

| Anesthesia | General or regional |

| Trauma (nonischemic) | Straddle injury, coital injury, pelvic trauma, intracavernous injection needle injury |

| Iatrogenic (nonischemic) | Penile revascularization surgery, intracavernous needle injury, shunt surgery |

Recurrent ischemic priapism (RIP)

RIP, also known as stuttering priapism, involves repeated episodes of ischemic priapism with intervening periods of detumescence.2 The natural history of RIP is heterogeneous; most episodes are transient and self-remitting, often occurring during sleep and lasting for <3 hours.3 However, RIP is considered a harbinger of major ischemic priapism. In fact, nearly 30% progress to major episodes7,11 and >70% of SCD patients with a history of severe priapism have a history of RIP.6 Despite the relatively shorter duration, RIP is associated with a risk of cavernosal fibrotic injury and may lead to ED in 29% to 48% in patients.6,7,33

Nonischemic priapism

Nonischemic (also known as high-flow or arterial) priapism is a non-emergent variant of persistent erections caused by unregulated cavernous arterial inflow and occurs in less than 5% of observed clinical presentations.2,20,34 This variant is typically consequent to disruptions of the cavernous arterial supply involving mechanisms of injury, including arterial aneurysm, arterio-venous fistula, iatrogenic needle injury, or pelvic trauma resulting in arteriolar-sinusoidal fistula formation.11,20 Following trauma, fistula formation allows blood from the cavernous artery to enter the lacunar spaces rather than the helicine arteries, resulting in unregulated penile engorgement.35 Contrary to these “classic” mechanisms of nonischemic priapism, several reports have identified this phenomenon in the absence of anatomical abnormalities and particularly in the presence of SCD.8,36 This may suggest a role of hematologic disorders in the development of this characteristic hyperemic environment, although the underlying mechanism is unknown.37 In this variant, the corpora are usually tumescent, typically lacking rigidity and pain,2 and episodes may spontaneously resolve with little or no complications.11

Pathophysiology of RIP

Until recently, the classic vaso-occlusive paradigms of erythrocyte sludging within vascular spaces associated with SCD fostered the belief that vascular stasis and increased viscosity in the penis were the primary causes of this disorder.38 Emerging evidence has uncovered a likely molecular basis underlying RIP in SCD involving decreased NO bioavailability.

Studies with mouse models of SCD that exhibit priapism found aberrations in NO signaling as a primary mechanism underlying priapism.39 This and other mouse models of priapism exhibit decreased PDE5 production and basally lower cGMP levels.39 cGMP is reduced secondary to a chronic decrease in the production of endothelium-derived NO, which results from vasculopathic damage in SCD.39-42 Hemolysis also serves as a basis for decreased NO because free Hb avidly scavenges intravascular NO. Arginase is also released from hemolyzed red cells, which reduces l-arginine, a substrate for NO production. Furthermore, excessive reactive oxygen species production, a chronic state in SCD, also impairs endothelium-derived NO formation and function.43-45

With neurologic erectogenic stimulation, which can occur with sexual activity or sleep, neuronally derived NO production increases cGMP levels to promote cavernosal relaxation. However, downregulation of basal PDE5 levels results in an inability to adequately terminate the resulting downstream vasodilatory effects of heightened cGMP release (Figure 1). Thus, the erectile response is uncontrolled, and the penis becomes priapic. Additional signaling pathways involving RhoA/ROCK, adenosine, and opiorphin pathways have been implicated in the molecular pathophysiology of priapism.13,46-48

Diagnosis

The goal of initial assessment lies in distinguishing between the ischemic and nonischemic variants. An appropriate evaluation is essential because ischemic priapism is a urologic emergency. As such, history, physical examination, laboratory testing, and imaging are useful tools in determining both the etiology and subsequent treatment modality.

History and physical examination

Prolonged pain is an important predictor of ischemic priapism. Clinical histories should also include duration, circumstances associated with onset, co-morbid conditions (SCD or coagulation disorders), a history of previous episodes, pharmacotherapy (erectogenic, psychoactive, or recreational drugs), alleviating maneuvers, prior treatments, and previous erectile function. Physical examination should include an evaluation of the phallus by inspection and palpation to determine the extent of tumescence, as well as overall for signs of trauma, hematologic malignancy, or evidence of hemolytic disease. Unlike nonischemic priapism, ischemic priapism is characterized by the presence of rigidity and tenderness of the cavernosal bodies with absence of glans/penis involvement.

Laboratory testing

Corporal aspiration and blood-gas analysis from the priapic penis is crucial in diagnosing ischemic priapism.2 The presence of acidosis, hypoxia, and hypercapnia (pH <7.25, PO2 <30 mm Hg, and PO2 >6 mm Hg, respectively) indicates ischemic priapism, while cavernous blood gases are similar to that of arterial blood in non-ischemic priapism.2 The presence of hematologic or coagulation disorders should also be assessed because patients may be unaware of an underlying hematologic disorder.49 Finally, urine toxicology and drug screens can aid in determining pharmacotherapeutic or recreational drug use.2

Imaging

Penile imaging using color duplex ultrasonography can be valuable in diagnosing ischemic priapism in the emergent setting. Ischemic episodes are characterized by decreased or absent cavernosal arterial flow, whereas nonischemic episodes demonstrate normal to high arterial flow velocities.50 Frog-leg positioning during ultrasonography allows for examination of the entire penile shaft in addition to the perineum in order to identify anatomical malformations (ie, fistulae), as well as straddle or scrotal injuries.20,50 Penile duplex ultrasonography may be used independently, but can supplement corporal blood-gas analysis findings when diagnostic results are unclear. Repeat ultrasonography may be useful during interim evaluations to inform therapy.21 Penile arteriography can be used to localize and facilitate embolization of arteriolar-sinusoidal fistula in nonischemic priapism, although this approach, along with cavernosography and magnetic resonance imaging, are not commonly used for diagnosis.11,21

Management

Ischemic priapism of longer than 4 hours duration prompts attention and urges utilization of step-wise (least to more invasive) therapeutic maneuvers (Figure 2). The objective in management is to correct the compartment syndrome, re-establish blood flow, and relieve pain. Prior to seeking medical attention, patients often report using strategies such as exercise (“steal syndrome”), warm or cold compresses, oral hydration, and ejaculation with widely varying levels of success.6,11 The efficacy of these methods lacks evidence. However, they can be used early on if historically successful and they do not delay timely medical attention.11

Clinical pharmacoprevention

Because the goals of clinical and pharmacologic management differ based on the etiology, a thorough evaluation is necessary to construct a proper treatment plan. The goal of RIP management is prevention of subsequent episodes in order to reduce the significant risk of progression to a major episode, as well as risk of ED inherent to RIP episodes.33 Low-dose PDE5 inhibitors, when taken daily and unassociated with sexual stimulation, have demonstrated some benefit in reducing RIP occurrences. Therapy is based on the rationale of restoring penile NO balance with improved PDE5 function.51-53 This regimen attempts to modulate the molecular aberrations associated with RIP and differs from its use as an erectogenic therapy. We recommend a trial of PDE5 inhibitor therapy consisting of sildenafil (50 mg daily, unassociated with sexual stimulation) in patients with frequent RIP. Of note, there was an increased risk of vaso-occlusive crises and hospitalization for SCD patients treated with sildenafil for pulmonary hypertension during the walk-PHaSST trial, although the dose and frequency of sildenafil was significantly higher (20 mg to 80 mg, 3 times daily).54 We have found that sildenafil therapy for RIP is generally safe. Further studies demonstrating efficacy will be helpful to extend these preliminary findings.51-53

Hormonal modulation with chemical androgen inhibition or ablation is also used as an alternative approach to manage RIP. Antiandrogenic agents such as ketoconazole (an antifungal drug with antiandrogenic effects) block androgen binding or production. Tropic and trophic analogs, such as leuprolide acetate and stilboestrol, downregulate pituitary gland function or reduce serum testosterone levels through negative feedback of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, respectively. Although single case reports and small studies have demonstrated some efficacy for RIP, these alternatives are principally unproven as prophylactic agents because they have not been tested in large series.55-62 Additionally, they are associated with significant side effects including decreased libido, gynecomastia, delayed growth/development due to premature epiphyseal plate closure, and could mask prostate-specific antigen elevations.63,64 They are therefore, contraindicated in boys who have not completed sexual maturation and men wishing to conceive.2 Conventional antiandrogenic therapies may represent a nonspecific approach for priapism management as they interfere with erectile tissue structure and function.65 In contrast to clinical recommendations to suppress testosterone action, testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) has recently emerged as a potential management option. Despite isolated case reports describing TRT as a precipitant of priapism, recent clinical studies have not found an association and elevated testosterone levels have never been demonstrated in RIP.66-68 Given the critical role of androgens in erection physiology, particularly in regulating NOS and PDE5 expression,69-71 and the high prevalence of hypogonadism among SCD patients with priapism,68 emerging evidence suggests that TRT may be beneficial by restoring NO regulation.65,69 Further studies of TRT in priapism are ongoing.

Hydroxyurea, the only US Food and Drug Administration-approved drug for treating SCD, inhibits DNA synthesis during the S-phase of the cell cycle and increases fetal Hb, thereby decreasing Hb S polymerization and sickling.65 Although this agent can reduce vaso-occlusive crises and increase life expectancy in SCD patients, its effectiveness in preventing RIP is unclear. Case reports suggest some prophylactic benefit.72,73 As hydroxyurea is an NO donor, it could function through this mechanism.74 Hydroxyurea reacts with Hb to form NO, and could increase bioavailable NO.75,76 The increase in fetal Hb associated with a decrease in hemolysis could also enhance NO bioavailability.77 Although there may be a potential role for hydroxyurea in preventing RIP, there is no evidence to support its role in acute episodes.11

The resolution of priapism using red cell exchange or simple transfusions has been described in anecdotal reports. However, its use to prevent or treat acute episodes remains controversial, as well-substantiated evidence for benefit is lacking.28,78-80 Moreover, prior reports described serious neurologic complications associated with red cell exchanges or simple transfusions for priapism, including convulsions, hemiparesis, and cerebral hemorrhages.28,78,80,81 Consequently, a recent expert panel recommended against the use of transfusion therapy for the treatment of priapism.82

Medical treatment

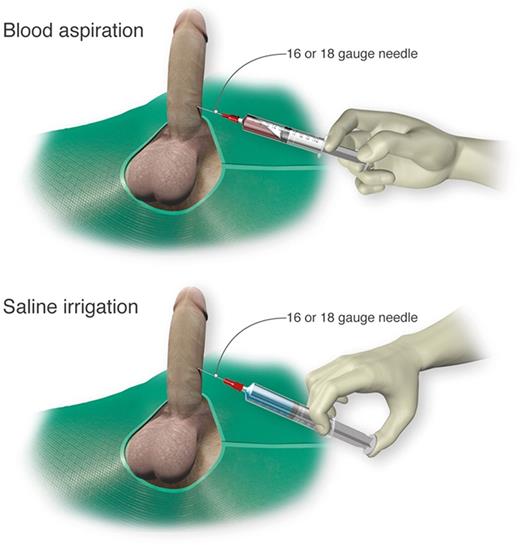

Self-injection (following teaching in clinic) of a prescribed α-adrenergic sympathomimetic, such as phenylephrine, is offered as a management approach after 1 to 2 hours of RIP although this intervention is not truly preventative.2 The goals for therapy for prolonged, severe episodes of ischemic priapism include pain relief, often with opioid analgesics, and prompt penile detumescence. This is paramount in order to prevent or decrease corporal ischemic damage and necrosis that is associated with ED.11 When ischemic priapism occurs in the setting of an underlying etiology, such as SCD or other hemolytic diseases, appropriate systemic treatment should be combined with intracavernous treatment.4 A major episode of ischemic priapism requires immediate treatment to limit ischemia from the compartment syndrome. Antibiotics (1 to 2 gm IV cefazolin) should be considered prior to treatment. We recommend a local penile shaft block to provide local pain control for the ensuing maneuvers.1 A 16 or 18 gauge needle is then inserted directly into the corpus cavernosum at the lateral aspect of the proximal penile shaft to aspirate blood (Figure 3), which has both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.4 Alternate needle placements from a transglanular intracorporal angiocatheter (16 or 18 gauge) insertion in the manner of the Winter shunt (discussed in following section, “Surgical management”) to proximal corpora cavernosal needle placement for maximal corporal body irrigation have been reported.83 Through this same needle, aspiration of blood, injection of an α-adrenergic sympathomimetic agent, and irrigation of the corpora cavernosa can be performed. Relief of the compartment syndrome through evacuation and irrigation of stagnant blood allows decompression of the corpora cavernosa and promotes the recovery of blood flow to the corpora. Early intervention is key to reversing the anoxic metabolic derangements caused by the priapism. Priapism resolution following aspiration with or without irrigation is ∼30%.2 To increase the efficacy of resolution, injection of phenylephrine, a potent vasoactive selective α1-adrenergic agonist that has important contractile effects (dosed 100 to 200 μg approximately every 5 minutes until detumescence, with 1000 μg/hour maximally) may be performed in combination with aspiration and irrigation.84

Cavernosal aspiration and irrigation of the penis. For treatment of an acute major ischemic priapism episode, a 16 or 18 gauge needle is inserted into the corpus cavernosum to aspirate blood, irrigate with saline, and inject sympathomimetics as necessary. Professional illustration by Luk Cox, Somersault18:24.

Cavernosal aspiration and irrigation of the penis. For treatment of an acute major ischemic priapism episode, a 16 or 18 gauge needle is inserted into the corpus cavernosum to aspirate blood, irrigate with saline, and inject sympathomimetics as necessary. Professional illustration by Luk Cox, Somersault18:24.

Aspiration with or without irrigation with use of sympathomimetic drugs or α-adrenergic agonists has a reported resolution rate of up to 80%.85 Of availably used sympathomimetics, phenylephrine is preferred due to its low risk of systemic cardiovascular effects through decreased β-adrenergic activity.86-88 The risk of systemic side effects is further reduced by intracavernosal injections. Nonetheless, patients are routinely monitored for systemic side effects including blood pressure and electrocardiogram monitoring, particularly in patients with high cardiovascular risk.89 The above maneuvers may need to be performed and repeated over several hours. Success is achieved when aspiration results in freshly oxygenated blood drawn back, and there is resolution of pain as well as penile detumescence. The patient may need to be monitored if findings on re-examination are equivocal or if there is concern for recurrence. If the above maneuvers fail, surgical options should be considered as second-line therapy. There is no clear consensus on when to perform second-line options, although trying first-line treatments for at least 1 hour before applying second-line therapies is suggested. Exceptions to this principle may be a continuous priapism episode lasting >72 hours.

Surgical management

Surgical management of ischemic priapism is customarily considered if first-line therapies fail to resolve the priapism episode, or if the clinical history and review of prior therapies suggest that surgical management should be offered initially. The International Society of Sexual Medicine recommends that penile shunting procedures be considered for priapism episodes lasting >72 hours, as “first-line” therapies are less likely to be effective. Prior to surgical intervention, it is paramount that a thorough, well-documented discussion occurs between the surgeon and patient, as this is a condition with a disproportionate level of medical-legal consequences. In addition to discussing the indications, risks, and benefits of the procedure, the patient should understand that the duration of priapism and resultant injury to corporal tissue, including necrosis and fibrosis, place him at high risk of permanent ED despite surgical intervention.

The objective of shunting procedures is to establish a communication between the sinusoids of the corpora cavernosa and the glans, corpus spongiosum, or vein for drainage to allow egress of blood. This involves making a window through the tunica albuginea. In general, the selection of shunting procedures is largely dependent upon the familiarity and comfort-level of the practitioner. The distal shunt, a corporaglanular shunt, is generally preferred because it is easier to perform, and has lower complication rates when compared with proximal shunts. There are several variants from percutaneous to open approaches,90-96 which can be followed by penile prosthesis implantation. Proximal shunting has been reserved for priapism episodes refractory to distal shunting because it is a more complex procedure with higher complication rates. Proximal shunting involves creating a window between the corpus cavernosum and corpus spongiosum at the level of the crura, typically through a perineal or transscrotal approach or utilization of venous anastomoses to shunt blood out of the corpora.97-99 Shunting procedures carry inherent risks of complications such as ED, infection, urethrocavernous fistulas, cavernositis, and urethral strictures.100

Complications that result from such shunting procedures should be distinguished from the risk of the disease, such as ED or changes in sensation. Complete detumescence may not be achieved due to turgor and edema. Penile color duplex ultrasonography can be used to confirm return of cavernosal blood flow. High flow priapism has been reported to occur following shunting with return of heightened blood flow in the cavernosal arteries as demonstrated by ultrasonography.101,102

Early penile prosthesis implantation is a third option, particularly in adult patients, that may be selected based on the likelihood of permanent ED. Priapism episodes lasting continuously for >36 hours are almost invariably associated with permanent ED. This time-frame may be altered as patients undergo treatments that achieve partial restoration of blood flow, but later fail. Thus, some urologists recommend 72 hours from the initial event as a cutoff for strongly considering early penile prosthesis to reduce fibrosis and maintain penile length.23 Recommendations exist for penile prosthesis surgery in cases of refractory RIP as well. However, these uses are controversial. For major priapism, it may be difficult to obtain a well-deliberated consent from a distressed patient as well as timely approval for insurance cost-coverage.103 Ultimately, the decision for penile prosthesis surgery must be reached jointly with the patient, based on goals and risk/benefit determinations.

The principles of priapism management are largely similar in both pediatric and adult populations, with technical exceptions relating to corporal aspiration volumes, sympathomimetic dosing, and anesthesia considerations.104

Future perspectives

Adequate prophylactic management strategies for RIP are lacking. Recent studies identifying multiple complementary signaling pathways underlying the pathophysiology of RIP offer new and exciting therapeutic approaches for RIP prevention and management. Recognition of the roles of NO, RhoA/ROCK, adenosine, and opiorphins may lead to the development of future agents potentially targeting these molecular effectors.39,46-48,105,106 Strategies involving the use of PDE5 inhibitors to correct the underlying aberrations in NO balance have met with some success, as well as challenges regarding cost and patient adherence.51-53,107 Preclinical investigations in animal models of SCD have uncovered alternative methods of restoring NO balance through the use of sustained NO-releasing compounds.108 The success of orinthine decarboxylase inhibitors and adenosine deaminase enzyme replacement in animal models as modulators of opiorphin and adenosine pathways, respectively, have also showed potential promise as plausible therapies in reducing the risk of priapism recurrence.47,109,110

The management of priapism should involve a multidisciplinary approach. Patient education and clinical cooperation are necessary in addressing the deficiencies created by our current health care policy.111 The higher prevalence of priapism among patients with hematologic and coagulation disorders requires comprehensive management strategies engaging hematologic and urologic care providers. Collaborative efforts within the medical community will be essential to advance treatment strategies.

Authorship

Contribution: U.A.A. and B.V.L. performed literature searches and prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and L.M.S.R. and A.L.B. reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Arthur L. Burnett, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Marburg 407, 600 North Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD 21287-2101; e-mail: aburnet1@jhmi.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal