Abstract

The thalassemias, together with sickle cell anemia and its variants, are the world’s most common form of inherited anemia, and in economically undeveloped countries, they still account for tens of thousands of premature deaths every year. In developed countries, treatment of thalassemia is also still far from ideal, requiring lifelong transfusion or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Clinical and molecular genetic studies over the course of the last 50 years have demonstrated how coinheritance of modifier genes, which alter the balance of α-like and β-like globin gene expression, may transform severe, transfusion-dependent thalassemia into relatively mild forms of anemia. Most attention has been paid to pathways that increase γ-globin expression, and hence the production of fetal hemoglobin. Here we review the evidence that reduction of α-globin expression may provide an equally plausible approach to ameliorating clinically severe forms of β-thalassemia, and in particular, the very common subgroup of patients with hemoglobin E β-thalassemia that makes up approximately half of all patients born each year with severe β-thalassemia.

Introduction

Thalassemia is the most common form of all inherited disorders of the red cell.1 It is estimated that 70 000 children are born with various forms of thalassemia each year, and more than half of these births are affected by severe forms of β-thalassemia, of which the most common subgroup is hemoglobin (Hb) E β-thalassemia.2,3 Thalassemia was originally confined to the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, distributed throughout the Mediterranean, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and the southern regions of Asia. However, as a result of relatively recent migration, many north European and North American countries are now home to large numbers of patients with thalassemia.4

Despite being one of the first molecular diseases to be identified and have its pathophysiology understood, the management of β-thalassemia still largely depends on supportive care, with regular lifelong red blood cell transfusions and iron chelation.5 In economically poor countries, affected individuals still die as children. However, even in developed countries, most patients with β-thalassemia still have reduced life expectancy and often experience a relatively poor quality of life.6 Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, the only curative treatment option, is not feasible for most patients, even in economically developed countries, because of a lack of suitable donors. Furthermore, this treatment is still associated with a significant risk for mortality and morbidity, especially when the donor is not related.1

Over the course of the last 30 years, many new and experimental approaches to the treatment of thalassemia have been considered and developed; however, none has progressed to the level of significant clinical use.7,8 Gene therapy has made noteworthy, albeit slow, progress and is being tested in clinical trials in a limited number of patients.9-11 However, the reported risks associated with the procedure, including development of leukemia by activation of proto-oncogenes, means much further work will be required to develop this as a common treatment.12 Pharmacological augmentation of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) production has been a long-standing therapeutic objective and is already in clinical use for patients with severe sickle cell disease.13 Three different classes of HbF-inducing agents have been tested in patients with thalassemia, including chemotherapeutics/hypomethylating agents (hydroxyurea, 5-azacytidine, and decitabine), short chain fatty acid derivatives (sodium phenylbutyrate), and erythropoietin; however, with the exception of hemoglobin S β-thalassemia, none has been able to produce a sustainable clinical response.14 There has been a report of activation of δ-globin gene expression in an animal model to enhance production of HbA2, but its clinical usefulness needs further consideration.15 Hence, it is clear there is still a great need for new, alternative, and effective therapeutic strategies for treatment of this life-limiting disease to render patients transfusion-independent and able to live a normal life.

In patients with β-thalassemia, the primary damage to the red cells and their precursors is mediated via excess α-globin chains that accumulate when β-globin expression is reduced.16,17 A number of case-control and cohort studies have demonstrated that a natural reduction in α-globin chain output, resulting from coinherited α-thalassemia, is beneficial in patients with β-thalassemia (described in detail here). Therefore, reducing α-globin chains in patients with β-thalassemia is a potential pathway to developing new therapies. Advances in our understanding of the precise epigenetic regulation of α- and β-globin genes in erythroid cells, development of new drugs targeting specific epigenetic pathways, and the advent of genome engineering using programmable, sequence-specific endonucleases make it possible to consider new strategies for selective control of α-globin expression in patients with β-thalassemia. In this review, we summarize current molecular and clinical data rationalizing the use of α-globin as a valid target in treatment of β-thalassemia and present plausible new strategies that can be used to achieve this goal.

Molecular basis of β-thalassemia

At the molecular level, synthesis of hemoglobin is controlled by 2 multigene clusters located on chromosome 16 (encoding the α-like globin genes) and chromosome 11 (encoding the β-like globin genes).1 In each cluster, these genes are arranged along the chromosome in the order in which they are expressed during development to produce different types of hemoglobin (Figure 1). During fetal life, the predominant form of hemoglobin produced is HbF (α2γ2), which is then switched to adult-type hemoglobin HbA (α2β2) after birth.18

Schematic diagram of α- and β-globin gene clusters and the types of hemoglobin produced at each developmental stage. Genes are arranged along the chromosome in the order in which they are expressed during development; (A) in the α-cluster ζ (embryonic) and α (fetal and adult); (B) in the β-cluster ε (embryonic), γ (fetal), and δ and β (adult). The 4 upstream regulatory elements of the α-locus are known as MCSR1 to MCSR4, whereas the 5 regulatory elements of the β-locus are collectively referred to as locus control region (LCR). The hemoglobin types expressed during different stages of development are embryonic (Hb Gower-I [ζ2ε2], Hb Gower-II [α2ε2], and Hb Portland [ζ2γ2]), fetal (HbF [α2γ2]), and adult (HbA [α2β2] and HbA2[α2δ2]).

Schematic diagram of α- and β-globin gene clusters and the types of hemoglobin produced at each developmental stage. Genes are arranged along the chromosome in the order in which they are expressed during development; (A) in the α-cluster ζ (embryonic) and α (fetal and adult); (B) in the β-cluster ε (embryonic), γ (fetal), and δ and β (adult). The 4 upstream regulatory elements of the α-locus are known as MCSR1 to MCSR4, whereas the 5 regulatory elements of the β-locus are collectively referred to as locus control region (LCR). The hemoglobin types expressed during different stages of development are embryonic (Hb Gower-I [ζ2ε2], Hb Gower-II [α2ε2], and Hb Portland [ζ2γ2]), fetal (HbF [α2γ2]), and adult (HbA [α2β2] and HbA2[α2δ2]).

β-Thalassemia is characterized by absent or reduced production of β-globin chains and HbA. Worldwide, nearly 300 mutations in and around the β-globin gene have now been reported to cause β-thalassemia.19 Most are point mutations either in the gene or its immediate flanking regions, but some are caused by small deletions removing all or part of the β-globin gene. Some rare β-thalassemias are caused by deletions removing the upstream regulatory elements (collectively referred to as the β-globin locus control region), leaving globin genes intact. The mutation associated with the very common structural hemoglobin variant hemoglobin E also leads to abnormal, inefficient splicing of the associated β-globin gene, resulting in a phenotype of β-thalassemia.20,21

Cellular pathology of β-thalassemia

During every stage of development, production of α-like and β-like globin chains are balanced.1 However, in patients with β-thalassemia, impaired production of β-globin chains results in an excess of free α-globin chains that undergo denaturation and degradation in mature erythroid cells and their precursors to play a critical role in the causation of anemia.22

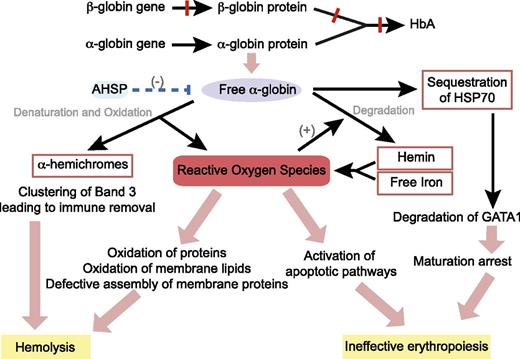

In 1960s, Fessas first described the presence of inclusion bodies, which consist of precipitated α-globin chains in erythroid cells of patients with β-thalassemia.23-25 Within cells, the erythroid-specific molecular chaperone α hemoglobin stabilizing protein specifically binds to multiple forms of α-globin (apo, ferrous, and ferric) and stabilizes free α-chains by promoting protein folding and resistance to protease digestion.26 However, when the capacity of α hemoglobin stabilizing protein is exceeded, highly unstable free α-globin molecules undergo auto-oxidation, forming α-hemichromes (α-globin monomers that contain oxidized ferric iron) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) to trigger cascades of events leading to hemolysis and ineffective erythropoiesis (Figure 2).5,27,28

Pathophysiology of β-thalassemia. Absent or reduced β-globin production leads to an unbalanced excess of α-globin chains, which then trigger cascade of events through the generation of ROS, resulting in hemolysis of mature red blood cells and destruction of immature erythroid precursors in the bone marrow (ineffective erythropoiesis). AHSP, α hemoglobin stabilizing protein; HSP70, heat shock protein 70.

Pathophysiology of β-thalassemia. Absent or reduced β-globin production leads to an unbalanced excess of α-globin chains, which then trigger cascade of events through the generation of ROS, resulting in hemolysis of mature red blood cells and destruction of immature erythroid precursors in the bone marrow (ineffective erythropoiesis). AHSP, α hemoglobin stabilizing protein; HSP70, heat shock protein 70.

The α-globin monomers are degraded via several pathways including an adenosine triphosphate and ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic pathway, an autophagy pathway, and a nonenzymatic pathway triggered by ROS to result in the release of hemin (heme containing oxidized ferric iron) and free iron, which lodges in the cell membrane.29-32 In addition, α-hemichromes are also found bound to the cytoskeleton.27 In this unstable conformation, both the heme group and the iron are able to participate in redox reactions, leading to further generation of ROS, which damage cellular proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.33 ROS-induced alterations in membrane deformability and stability through partial oxidation of protein band 4.1 and defective assembly of spectrin-actin-band 4.1 membrane skeleton complex are believed to be the primary mechanism of hemolysis in mature red cells.34 In addition, oxidant injury leads to clustering of band 3, which in turn produces a neoantigen that binds to immunoglobulin G and complement, thereby signaling macrophages to remove them from the circulation.35

Ineffective erythropoiesis and death of bone marrow erythroid precursors at the polychromatic stage, however, are not explained by membrane damage and appear to be a result of enhanced activation of the apoptosis pathways.22 In nonerythroid cell models, ROS have been reported to induce apoptosis by activating apoptosis signal regulating kinase 1 and jun-kinase; this mechanism may contribute to erythroid cell apoptosis in thalassemia.36 In addition, there is evidence that apoptosis in thalassemic red blood cells is mediated by the Fas cell surface death receptor (FAS) and FAS-ligand pathway, which is triggered by high levels of ROS.37 A recent study has demonstrated that heat shock protein 70 interacts directly with free α-globin chains, and thereby becomes sequestered in the cytoplasm. This, in turn, prevents the protein from performing its normal physiological role of protecting GATA-binding factor 1 (GATA1) from proteolytic cleavage. The resulting premature degradation of GATA1 results in maturation arrest and apoptosis of polychromatic erythroblasts.38 Therefore, it is clear that excess free α-globin is directly responsible for both hemolysis and ineffective erythropoiesis, which are the 2 primary pathophysiological mechanisms causing anemia in patients with β-thalassemia.

Genetic modifiers of β-thalassemia

β-Thalassemia is the archetypal monogenic disorder and, as such, has established the principle that such disorders display a remarkable clinical heterogeneity. In β-thalassemia, we know that the clinical severity is directly related to the degree of imbalance between α-like and β-like globin chain synthesis in erythroid cells. This can be partly explained by the nature of the mutations: Some β-thalassemia mutations, which are referred to as β0-thalassaemias, cause complete abolition of β-globin gene expression, whereas others, known as β+- or β++-thalassemias, result in variable reduction of β-globin chain synthesis.39 However, there is also remarkable clinical variability, even in patients who inherit identical β-globin genotypes.

Again, studies in β-thalassemia have most clearly demonstrated the influence of modifiers of single gene disorders. Coinheritance of genetic determinants that increase the production of γ-globin chains and HbF increase the β-like globin chain pool in erythroid cells, improve α-like/β-like globin chain balance, and reduce the severity of β-thalassemia. Genetic polymorphisms identified in quantitative trait loci including the Xmn1-HBG2 variant in the β-globin cluster, the HBS1L-MYB intergenic region on chromosome 6, the gene encoding B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 11A protein (BCL11A) on chromosome 2, and the Kruppel-like factor 1 (KLF1) mutations40,41 are known to be associated with high HbF levels.42 These associations have been well characterized and are being used to develop new therapeutic strategies. These strategies have been extensively reviewed13,43-45 and are not discussed any further in this review.

Coinheritance of α- and β-thalassemia

Coinheritance of factors that lower α-globin production, as in α-thalassemia, reduces the free intracellular α-globin pool, improves α-like/β-like globin chain balance, and since the initial descriptions by Fessas46 and Kan and Nathan,47 has been predicted to ameliorate the severity of β-thalassemia.42 Coinheritance of α- and β-thalassemia is common in areas in which the gene frequencies of both types of thalassemia are high, especially regions of the world in which heterozygous thalassemia provides a natural selective advantage in the presence of endemic falciparum malaria.48 Results of a number of family, cohort, and case-control studies in various ethnic groups exploring the outcomes of the coinheritance of α- and β-thalassemia can be summarized as follows: deletion of 2 α-globin genes (−/αα or −α/−α) is associated with a milder clinical phenotype in most patients with β-thalassemia, and deletion of a single α-globin gene (−α/αα) is beneficial in patients other than those with the most severe reduction in β-globin synthesis (β0/β0 genotype).47,49-59 However, a recent study performed as a follow-up of a genomewide association study among a relatively uniform group of patients with the β0/β0 genotype revealed that even a single α-globin gene deletion significantly increases the chance of having a thalassemia intermedia phenotype, as opposed to thalassemia major. Furthermore, this study also showed that the presence of a mutated α-globin allele provided an additive effect to other modifier alleles responsible for modulating high HbF levels.60 Similar results were found in another study that used multivariate analysis and concluded that α-thalassemia is a significant independent predictor for a milder phenotype.61

Of all β-thalassemia subtypes identified throughout the world, the most common genotypes are those associated with HbE β-thalassemia. This disease, which is seen commonly throughout parts of South and Southeast Asia, constitutes about 50% of births with severe thalassemia. Importantly, coinheritance of α-thalassemia appears to have its most pronounced and unequivocal effect on patients with HbE β-thalassemia, with substantial clinical benefit even when only a single α-globin gene deletion (−α/αα) is coinherited. In large-scale prospective studies, all patients with coinherited α-thalassemia displayed a milder phenotype, older age at presentation, smaller splenic and hepatic sizes, normal physical and sexual maturation, and significantly reduced transfusion requirements.59,62-66 Furthermore, in HbE β-thalassemia patient cohorts, the frequency of α-thalassemia is significantly lower than in the normal matched population, and it is extremely rare to find patients with 2 α-globin gene deletions (−/αα or −α/−α).64,66 These observations suggest that individuals with HbE β-thalassemia who coinherit only 2, rather than the normal 4, α-globin genes have a very mild phenotype and are rarely brought to medical attention. Contrary to the beneficial effect demonstrated by coinheritance of α- and β-thalassemia, inheritance of excess α-globin genes worsens the α-like/β-like globin chain imbalance and results in a more severe clinical phenotype.67-69 This observation further emphasizes that the number of functional α-globin genes has a clear direct effect on the clinical severity of patients with β-thalassemia.

Reduction of α-globin output as a therapeutic option for β-thalassemia

The clinical and genetic evidence accumulated during the last 30 years strongly supports the idea that reducing α-globin expression in patients with β-thalassemia is an important area for developing a new therapy. Reductions of α-globin output to levels comparable to single or 2 α-globin gene deletions should be clinically beneficial to patients with β-thalassemia, and in patients with HbE β-thalassemia, it could be transformational. Among patients with α-thalassemia, single and 2 α-globin gene deletions correspond to 25% and 50% reductions, respectively, in α-globin output at both the messenger RNA and protein level, and these levels could be considered as rational therapeutic aims in β-thalassemia.70,71 Clearly, several obstacles need to be considered if this natural phenomenon is to be translated effectively into therapy. First, the α-globin loss should not be complete, and any decrease beyond 75% would be counterproductive and worsen anemia with loss of sufficient α-globin chains to produce hemoglobin. Second, the production of β-like globins should not be affected. Advances in our understanding of the genetic and epigenetic regulation of the α-globin gene cluster suggest it might be possible to selectively control α-globin expression to the appropriate degree to be useful for patients with β-thalassemia.

Regulation of α-globin gene expression

The human α-globin cluster is located at the short arm of chromosome 16, very close (∼150 kb) to the telomere in a gene-dense region of early replicating, open chromatin. The promoters of all genes within this region are associated with cytosine guanine dinucleotide-rich islands. α-Globin expression is controlled by 4 distant cis-acting regulatory elements (enhancers) associated with DNAse1 hypersensitive sites situated 10 (multispecies conserved sequence R4 [MCS-R4]), 33 (MCS-R3), 40 (MCS-R2), and 48 (MCS-R1) kb upstream of the genes (Figure 1). A variety of experiments including transient transfections and transgenics combined with naturally occurring human mutations suggest MCS-R2 (previously known as HS-40) is the most critical regulatory element capable of enhancing α-globin expression on its own.72 During erythroid differentiation, key transcription factors including GATA1, nuclear factor-erythroid 2 (NF-E2), stem cell leukemia (SCL) pentameric complex, and KLF1 are recruited into the remote regulatory elements, followed by recruitment of the preinitiation complex to both the enhancers and promoters, thereby initiating transcription.73 During this process, physical interaction between enhancers and promoters is believed to occur through a mechanism of chromatin looping.74

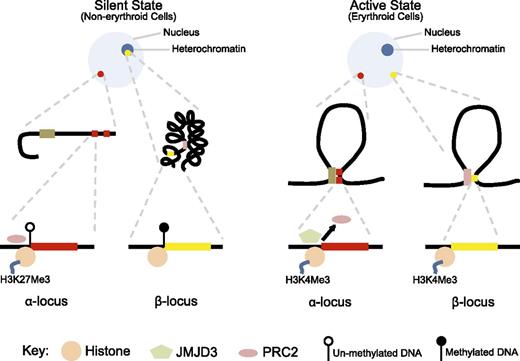

Significant changes are also noted in the chromatin environment during erythroid differentiation (Figure 3). In nonerythroid cells, the α-globin promoter is occupied by a protein complex known as the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which promotes methylation of a specific histone lysine residue to increase H3K27me3 chromatin modification, which signals transcriptional silencing.75 In erythroid cells, when the α-globin gene is activated, PRC2 is detached and the H3K27me3 chromatin mark is erased through passive and active mechanisms, including demethylation by Jumonji domain containing 3, histone lysine demethylase (JMJD3) enzyme.76 In contrast, the chromatin environment and silencing mechanism of the β-globin gene have significant differences to this (Table 1). β-Globin is situated in a relatively gene-sparse, methylated, and late-replicating region in an interstitial area of chromosome 11 that is in a closed heterochromatic environment in nonerythroid cells.77,78 In contrast to α-globin, the promoter of β-globin is not bound by PRC2 and does not have the repressive chromatin mark H3K27me3.75,79

Contrasting epigenetic landscape of α- and β- globin loci. In the silent, nonexpressed state (nonerythroid cells), the α-globin locus (red dot) is in open chromatin environment, whereas the β-globin locus (yellow dot) is in a closed chromatin conformation incorporated into heterochromatin (dark blue circle within the nucleus). The promoter of α-globin is unmethylated, bound by PRC2, and the associated histone has the H3K27me3 modification. In contrast, the β-globin locus is heavily methylated and does not show binding of PRC2 or the H3K27me3 chromatin modification. In the active state (erythroid cells), both loci are located away from heterochromatin and form loop structures to facilitate respective enhancer–promoter interactions, and both promoters show H3K4me3 active chromatin modification. However, only in the α-globin locus, PRC2 is detached and JMJD3 is recruited to facilitate removal of the H3K27me3 repressive chromatin modification.

Contrasting epigenetic landscape of α- and β- globin loci. In the silent, nonexpressed state (nonerythroid cells), the α-globin locus (red dot) is in open chromatin environment, whereas the β-globin locus (yellow dot) is in a closed chromatin conformation incorporated into heterochromatin (dark blue circle within the nucleus). The promoter of α-globin is unmethylated, bound by PRC2, and the associated histone has the H3K27me3 modification. In contrast, the β-globin locus is heavily methylated and does not show binding of PRC2 or the H3K27me3 chromatin modification. In the active state (erythroid cells), both loci are located away from heterochromatin and form loop structures to facilitate respective enhancer–promoter interactions, and both promoters show H3K4me3 active chromatin modification. However, only in the α-globin locus, PRC2 is detached and JMJD3 is recruited to facilitate removal of the H3K27me3 repressive chromatin modification.

Differences in the structure and function of the α- and β-globin gene clusters

| Characteristic . | α-globin cluster . | β-globin cluster . |

|---|---|---|

| Location | 16p13.3 telomeric | 11p15.5 interstitial |

| Guanine-cytosine content | 54% | 39.5% |

| Cytosine guanine dinucleotide-rich islands | Common | None |

| Gene density | High | Low |

| Chromatin | Open | Closed |

| Replication timing | Early | Late |

| Predominant mutations | Deletions | Point mutations |

| Evolution of intergenic regions | Rapid | Slow |

| Expression in hybrids | Early | Late |

| Binding of polycomb repressive complex | Present | Absent |

| H3K27me3 chromatin modification | Present | Absent |

| JMJD3 enzyme | Recruited | Not recruited |

| Characteristic . | α-globin cluster . | β-globin cluster . |

|---|---|---|

| Location | 16p13.3 telomeric | 11p15.5 interstitial |

| Guanine-cytosine content | 54% | 39.5% |

| Cytosine guanine dinucleotide-rich islands | Common | None |

| Gene density | High | Low |

| Chromatin | Open | Closed |

| Replication timing | Early | Late |

| Predominant mutations | Deletions | Point mutations |

| Evolution of intergenic regions | Rapid | Slow |

| Expression in hybrids | Early | Late |

| Binding of polycomb repressive complex | Present | Absent |

| H3K27me3 chromatin modification | Present | Absent |

| JMJD3 enzyme | Recruited | Not recruited |

Downregulation of α-globin expression by RNA interference

RNA interference (RNAi) mediated through small double-stranded RNAs, including small interfering RNA (siRNA) and short hairpin RNA (shRNA), has recently emerged as a powerful tool for posttranscriptional gene silencing.80,81 These double-stranded RNA molecules incorporate into a protein complex known as the RNA-induced silencing complex within the cytoplasm, where the strands are separated and 1 strand guides the RNA-induced silencing complex to the complementary region of target messenger RNA, suppressing gene expression either by degrading mRNA or blocking mRNA translation. Thus, RNAi produces efficient and specific gene silencing. Efforts to translate this new discovery into clinical applications for disease treatment has been reasonably successful, and clinical trials of RNAi therapies in treating cancer, cardiovascular diseases, infections, and eye diseases are in their early stages.82

Attempts to reduce α-globin expression using this technique have been reported. In an experimental model developed by Voon et al, in vitro differentiated β-thalassemia murine primary erythroid cells were transfected, with siRNA targeting the α-globin mRNA. This resulted in a 50% knockdown of α-globin gene expression.83 As expected, this was associated with reduction of intracellular ROS and significant phenotypic improvement. Xie et al performed an in vivo experiment to knock down α-globin expression by shRNA in a β-thalassemia mouse model.84 Lentiviral vectors of shRNA targeting α-globin were microinjected into β-thalassemia heterozygous mouse single-cell embryos, and a transgenic mouse was generated that produced 20% to 35% less α-globin. These mice demonstrated sustained phenotypic improvement in red cells with less poikilocytosis, fewer target cells, increased hemoglobin values and red cell counts, and low reticulocyte counts. The same group then directly injected siRNA plasmids targeting α-globin mRNA into the tail veins of the β-thalassemia mice and analyzed the effects.85 Reductions in poikilocytosis, target cells, and reticulocyte counts were observed after treatment. Red cell counts and hemoglobin levels were unchanged, however.

Significant challenges and a number of barriers still need to be overcome before RNAi-based therapies will be useful in the clinic. The key challenge is to develop safe and effective delivery methods.86 Double-stranded RNA molecules are negatively charged and do not readily cross the cell membrane. Traditional delivery methods relied on viral vectors such as retroviruses, lentiviruses, adenoviruses, and adeno-associated viruses, but several limitations including carcinogenesis, immunogenicity, broad tropism, limited packaging capacity, and difficulty of vector production have limited its clinical use.87 The recent development of nonviral delivery methods including nanoparticles and conjugate formulations to deliver siRNAs in vivo with high efficiency and low toxicity have produced considerable excitement in this field. However, poor stability of siRNA in the extracellular environment, difficulties in targeting them to the cells of interest, limitations in dose-titration, off-target silencing, and inherent toxicities and immunogenic potential of siRNA will also need to be addressed before the development of effective therapeutics, using this promising tool.81,88

Downregulation of α-globin expression by genome editing

Genome editing using sequence-specific programmable artificially engineered nucleases has not only revolutionized biomedical research as a powerful tool for investigating gene regulation but also provides a realistic approach to the treatment of human genetic diseases. These nucleases create double-strand breaks at specific chosen locations in the genome and, when repaired, create mutations at the targeted sites, resulting in either loss of gene function or disruption of noncoding regulatory sequences. There are 3 main families of engineered nucleases currently being used: zinc finger nucleases, transcription activator-like effector nucleases, and RNA-guided nucleases CRISPR–Cas9 (clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeat-CRISPR associated system). Precise targeting to a specific genomic location, high efficiency of mutagenesis, and fewer disruptions of the genome are the main advantages of programmable nucleases over traditional gene therapy approaches.89 Major challenges include delivery of these tools to the cells of interest, titration of efficiency of editing to get the correct balance between heterozygous and homozygous mutations, and the potential off-target effects, which are vastly underestimated by available computational programs.90

Genome editing using zinc finger nucleases is already being used successfully in humans to disrupt the C–C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) encoding gene in CD4+ T cells to promote HIV-1 resistance.91 In a recently published phase 1 clinical trial, a group of HIV-1-infected patients was successfully transfused with autologous zinc finger nuclease-CCR5-modified T-cells, and a follow-up phase 2 trial to evaluate safety and tolerance of treatment is currently ongoing.92 An approach similar to this could be used to modify hematopoietic stem cells to downregulate α-globin expression with a simple, single edit in patients with β-thalassemia. There is very clear evidence that the upstream enhancer element MCS-R2 plays a critical role in α-globin gene expression. In a rare naturally occurring deletion removing only the MCS-R2 region, individuals with a heterozygous mutation have a reduced α-globin chain output similar to that seen in mild α-thalassemia, which is desirable to produce a beneficial effect in β-thalassemia.93 A rare homozygote for this deletion has HbH disease, but importantly, no other abnormality, showing that this element can be removed with no other untoward effects.93 Therefore, disruption of this single element using programmable nucleases has the potential to be a very useful and simple therapeutic strategy in patients with β-thalassemia, and in particular for those with the common HbE β-thalassemia genotype.

Downregulation of α-globin expression by pharmacologic methods

Epigenetic drug targeting is a promising and rapidly developing area in therapeutics that aims to alter gene expression by affecting the chromosomal environment via specific epigenetic pathways. Many proteins have been identified that write, read, or erase epigenetic modifications, which include well-characterized processes such as DNA methylation, histone methylation, and histone acetylation.94 Nucleoside analog irreversible inhibitors of the DNA methyltransferases (eg, azacitidine and decitabine) have been approved for clinical use for many years. Shortly after their approval, histone deacetylase inhibitors vorinostat and romidepsin were approved, and a number of specific inhibitors of other epigenetic pathways are currently under development, with some entering clinical trials.95 Although the current main indications for epigenetic drugs are various forms of cancers, some drugs are being tested for nonmalignant diseases. In fact, multiple studies including phase 2 clinical trials are underway to evaluate the usefulness of vorinostat (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01000155) and decitabine (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01685515) as HbF-inducing agents for the treatment of sickle cell disease.

As outlined earlier, the chromatin environment and silencing mechanisms of α-globin and β-globin clusters show clear and striking differences. This distinction may be very useful in the development of therapeutic strategies, and it is likely that drugs or small molecules acting via altering the chromatin environment will have a differential effect on α- and β-globin expression. More precisely, drugs acting through the PRC2 pathway, histone methylation, and histone demethylation are likely candidates to be useful in this regard. If pharmacologically active small molecules could reduce expression of the α-globin genes without affecting the expression of the β-like globin genes, most barriers faced by RNAi or genome editing could be overcome. Delivery would not be a major problem, and dose titrations may not be too challenging once the pharmacokinetics are determined. Further transformation into clinical practice would be easier, development would be less costly, and the drug would become available for patients in developing countries who are at the greatest need of new approaches to the treatment of thalassemia.

However, many challenges still remain in epigenetic drug targeting. Most of the epigenetic proteins are associated, with thousands of genes throughout the genome, and hence could have numerous off-target effects including tumorgenesis.95 For instance, mutations in PRC2 promote lymphoid transformation, myelodysplastic syndrome, and leukemia.95 In hematopoietic stem cells, PRC2 suppresses genes involved in differentiation, cell-cycle, self-renewal, and apoptosis, and when PRC2 is mutated, hematopoietic stem cells failed to differentiate into mature blood cells and were prone to cell death.96

Conclusion

Clinical genetic data reported during the last 30 years have provided increasingly strong evidence that reduction of α-globin expression by 25% to 50% would ameliorate the clinical severity of many patients with β-thalassemia. Advances in our understanding of α- and β-globin gene regulation have opened up new pathways that could be used to achieve this goal. With this knowledge, it is apparent that therapeutic downregulation of α-globin expression is feasible by RNA interference, epigenetic drug targeting, or genome editing. Therefore, it appears timely that researchers explore these pathways to add strength to the armory of clinicians treating patients with thalassemia until definitive cure through gene therapy or mutation-specific genome editing becomes a reality. This will provide a clear example of “bedside to bench to bedside” research, demonstrating how clinical data help understand the basic physiology of gene regulation and pathophysiology of disease. In this way, knowledge gained from basic research can be translated back to the clinic.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sir David Weatherall, Chris Fisher, and David Clynes of the Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, United Kingdom, for suggestions and critically reading the manuscript. We also acknowledge Nicola E. Gray of the Computational Biology Research Group, Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, for computational support in figures. S.M. is a Commonwealth Scholar, funded by the UK government.

Authorship

Contribution: S.M. reviewed the literature and S.M., R.J.G., and D.R.H. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Douglas R. Higgs, MRC Molecular Hematology Unit, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Headington, Oxford OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; e-mail: doug.higgs@imm.ox.ac.uk.

![Figure 1. Schematic diagram of α- and β-globin gene clusters and the types of hemoglobin produced at each developmental stage. Genes are arranged along the chromosome in the order in which they are expressed during development; (A) in the α-cluster ζ (embryonic) and α (fetal and adult); (B) in the β-cluster ε (embryonic), γ (fetal), and δ and β (adult). The 4 upstream regulatory elements of the α-locus are known as MCSR1 to MCSR4, whereas the 5 regulatory elements of the β-locus are collectively referred to as locus control region (LCR). The hemoglobin types expressed during different stages of development are embryonic (Hb Gower-I [ζ2ε2], Hb Gower-II [α2ε2], and Hb Portland [ζ2γ2]), fetal (HbF [α2γ2]), and adult (HbA [α2β2] and HbA2[α2δ2]).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/24/10.1182_blood-2015-03-633594/4/m_3694f1.jpeg?Expires=1765889662&Signature=IzPEsczAikelFd01VfdSnz61R27FIQu7nLHLL8lp6ZKS72Hq3uJkq5OJMppwpWclhD3uN1vErc8bMJifcPfr6D832Jl3WU42dhhbezm2SEZnwpfxv6svI834jdhgQZmIB~nBxPYBrer-VAMgJOSsh7O~7F38IGUcF8f0PFDOh~~lU8uXOHMnQlgcPPeSUQy46rnZebk937SGv2EXfuAakF01Ibhqk9CafdyOymFZpC9jetvk3p-W1bHrV3LXbYUKSYDn90x2lnkbBYg6nkFJqcBAitbch3tkNNQBAkZH~B7LJnSfxg6LMLfBV-0XZ6BTPb7WxrrV~b3t96AWgP0J6w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)