In this issue of Blood, Arumugam et al report that long-term reduction of prothrombin (PT) expression results in diminished vascular inflammation, attenuation of multiple organ damage, and survival advantage in a mouse model of sickle cell disease (SCD).1

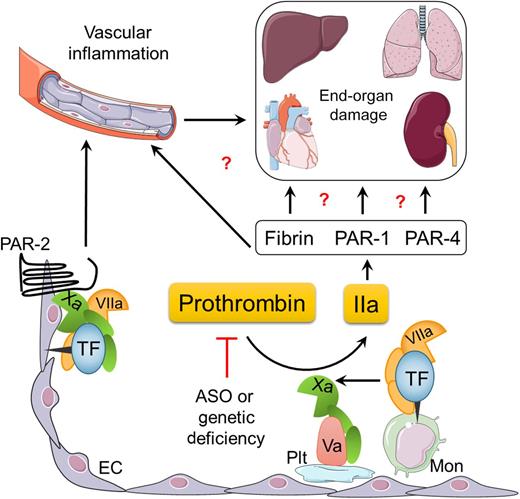

Proposed mechanisms by which the TF-thrombin pathway may contribute to the pathology of SCD. ASO, antisense oligonucleotides; EC, endothelial cell; IIa, thrombin; Mon, monocyte; PAR, protease-activated receptor; Plt, platelet. Illustration designed and prepared by Dr Erica Sparkenbaugh.

Proposed mechanisms by which the TF-thrombin pathway may contribute to the pathology of SCD. ASO, antisense oligonucleotides; EC, endothelial cell; IIa, thrombin; Mon, monocyte; PAR, protease-activated receptor; Plt, platelet. Illustration designed and prepared by Dr Erica Sparkenbaugh.

SCD is a hematologic disorder caused by a single nucleotide mutation in the β-globin gene, with hemolytic anemia and vaso-occlusive crises being the primary pathologies of the disease. Furthermore, SCD is also associated with chronic vascular inflammation and activation of coagulation.2 Increased expression of tissue factor (TF), the primary initiator of the extrinsic coagulation pathway, has been demonstrated in leukocytes and endothelial cells in sickle cell patients and in mouse models of SCD.2,3 Despite the well-documented hypercoagulable state of SCD, the question remains whether the activation of coagulation significantly contributes to the pathology of this disease or if it is merely a secondary event.

This question was partially addressed by a recent study demonstrating that inhibition of TF not only attenuated activation of coagulation but also reduced several markers of vascular inflammation in 2 mouse models of SCD.4 Interestingly, monocyte and endothelial cell TF contributed to the vascular inflammation via a thrombin-dependent and independent manner, respectively (see figure). Endothelial cell TF contributed to the increased interleukin 6 expression via factor Xa-dependent cleavage of PAR-2, but had no effect on activation of coagulation.4,5 Consistent with these results, inhibition of factor Xa with rivaroxaban, and thrombin with dabigatran, differentially affected markers of vascular inflammation.5 However, these studies were limited by a relatively short duration of treatment.

The study by Arumugam et al in this issue of Blood further expands our understanding of the prothrombotic state in SCD, where they investigated the long-term effects of either pharmacologic or genetic reduction of circulating levels of PT in sickle mice. In a series of elegantly designed experiments, the authors show that reduction of PT messenger RNA levels with antisense oligonucleotides significantly improves the survival of Berkley sickle mice.1 In separate experiments, sickle mice genetically engineered to express ∼10% of wild-type levels of PT were followed for 1 year. Low levels of circulating PT were associated with a significant reduction in vascular inflammation and, most importantly, in a lower incidence of end-organ damage (nephropathy, pulmonary hypertension, pathologic heart remodeling, and liver necrosis).1 These exciting data strongly support the concept that coagulation proteases are important components of SCD pathophysiology.

The precise mechanism(s) by which coagulation proteases contribute to the pathophysiology of SCD needs to be further elucidated (see figure). Does thrombin mediate pathologic effects in sickle mice via platelet and/or fibrin(ogen)-dependent mechanisms? Platelet activation and subsequent formation of platelet/neutrophil aggregates has been shown to exert detrimental effects in sickle mice6 and it is well documented that fibrin(ogen) promotes leukocyte-driven inflammation via the αMβ2 binding site on the γ chain of this molecule.7 The next question is whether activation of PARs by coagulation proteases, such as factor Xa (FXa) and thrombin, can contribute to vascular inflammation and end-organ damage observed in SCD. Does thrombin contribute to organ dysfunction directly or via enhancing vascular inflammation and/or vaso-occlusion? For example, coagulation-dependent activation of PAR-1 contributes to pathologic heart remodeling via hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes,8 and PAR-1 activation on endothelial cells promotes P-selectin–mediated vaso-occlusion.9 Finally, can the protective effect of reducing PT levels be recapitulated by long-term inhibition of thrombin activity using the new oral anticoagulants? Answering these questions could lead to future clinical trials investigating the potential benefit of the new direct-acting oral anticoagulants in patients with SCD.

Past clinical studies investigating the effect of anticoagulation in sickle cell anemia patients were inconclusive; however, most of these studies had a small number of patients, lacked placebo controls, and used pain crises as the only clinical end point (summarized in commented article). The only adequately powered and placebo-controlled study examined the effect of the low-molecular weight heparin tinzaparin, and demonstrated a significant reduction in the duration of pain crisis.10 Recently published data4,5 and the study by Arumugam et al1 strongly suggest that future clinical studies should evaluate as end points not only pain crisis but also vascular inflammation and markers of end-organ damage. In fact, such a study is already in progress. Using a crossover design, SCD patients will receive rivaroxaban 20 mg/day and placebo for 4 weeks each, separated by a 2-week washout phase to evaluate the effect of FXa inhibition on activation of coagulation, vascular inflammation, and microvascular blood flow (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02072668).

In conclusion, a growing body of evidence from animal studies indicates that the hypercoagulable state observed in SCD is not simply an epiphenomenon, but also significantly contributes to the pathophysiology of the disease. As always, animal studies have to be verified in clinical trials, and only then will we know if this is truly “PT time” for SCD. Based on the data by Arumugam et al, the author remains cautiously optimistic.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.