Abstract

The long-term prognosis of adult patients with relapsed Philadelphia chromosome–negative acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (ALL) is poor. Allogeneic stem cell transplant in second remission is the only curative approach and is the goal when feasible. There is no standard chemotherapy regimen for relapsed disease, although a few agents are approved for use in this setting. The bispecific CD19-directed CD3 T-cell engager, blinatumomab, has recently been granted accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration for relapsed or refractory disease of B-cell lineage. For patients with relapsed T-cell ALL, nelarabine is available. Liposomal vincristine is also approved for relapsed disease. When selecting combination chemotherapy salvage options, evaluation of the prior treatment and timing of relapse informs treatment decisions. Monoclonal and cellular investigational therapies are quite promising and should be explored in the appropriate patient.

Introduction

Remission rates for newly diagnosed adult patients with acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (ALL) are >80% with standard induction regimens.1-5 It is unfortunate that a subset of patients will be refractory to initial therapy and that an additional 30% to 60% of patients will relapse despite aggressive consolidation and maintenance chemotherapy regimens, including allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT).2,6-8 Adult patients with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome–negative (Ph−) ALL have a poor prognosis, and most patients will die of their disease.1,6,9-13 Remission rates at first relapse with standard salvage combination chemotherapy regimens range from 20% to 83% and are, in general, not durable with a chemotherapy-alone approach. In adults, long-term disease-free survival and cure in 7% to 24% of relapsed patients generally occurs only with allogeneic SCT.6,9,13,14 Predictors for outcomes include duration of first remission, response to initial salvage therapy, ability to undergo SCT, disease burden at time of SCT, and patient age.9

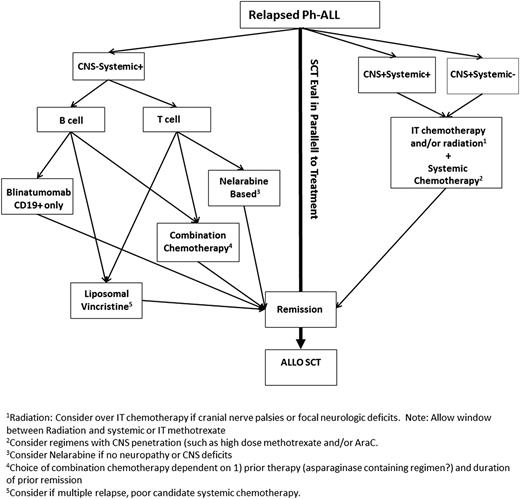

There is no standard approach to care for an adult in the relapsed and refractory setting, as witnessed by the lack of a real standard-of-care control arm on currently ongoing randomized trials. For patients who are candidates for salvage therapy, our choice of regimens takes into consideration features of the patient’s disease (immunophenotype, extramedullary involvement), patient age and comorbidities, goals of therapy, duration of prior remission, and type of prior therapy (Figure 1). The poor outcomes and lack of durable responses seen with conventional chemotherapy have led to the recent accelerated US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of several novel agents, including liposomal vincristine and blinatumomab, and previously, nelarabine.15-17 A surge of clinical trials exploring investigational monoclonal and cellular therapies are quite promising and will likely change the approach to chemotherapy-resistant disease in the near future.18-20

Treatment approach to an adult patient with relapsed Ph− ALL. Allo, allogeneic; AraC, cytarabine; CNS, central nervous system; IT, intrathecal.

Treatment approach to an adult patient with relapsed Ph− ALL. Allo, allogeneic; AraC, cytarabine; CNS, central nervous system; IT, intrathecal.

Here, we describe the clinical course of 3 adult patients with relapsed Ph− ALL to help illustrate our approach to management. In addition, given how rapidly promising agents are being developed, we highlight agents and investigative techniques that are likely to impact our approach to care in the near future.

Patient 1

N.J. presented at age 58 years with acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia associated with leukocytosis and cervical lymphadenopathy. Assessment for CNS involvement with lumbar puncture was negative. She achieved first complete remission (CR) with hyper-CVAD chemotherapy (alternating cycles of anthracycline, cyclophosphamide, prednisone, and vincristine with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine) with prophylactic IT chemotherapy. She failed to recover her peripheral blood counts after the fifth cycle of therapy and developed recurrent lymphadenopathy. A bone marrow biopsy and aspirate confirmed relapsed disease. Restaging of her CNS remained negative. She presented to us for treatment at that time.

In children who relapse, reinduction leads to a second remission in up to 85% of patients, and a chemotherapy-alone approach can result in long-term overall survival.21 For adults, however, long-term disease-free survival and cure for patients with relapsed or refractory disease is possible in <25% of patients and can generally occur only with allogeneic SCT.6,9,13,14 In a 2009 updated evidence-based review of management of adult ALL, allogeneic SCT is recommended over chemotherapy alone for ALL in second remission or greater.22 In a retrospective review of 547 adult patients with first relapse of ALL, no patient without SCT was alive after 1 year compared to 38% of patients who received allogeneic SCT after initial salvage therapy.9

Our initial approach to a patient such as this with relapsed ALL is therefore dependent in large part on whether the patient is a potential candidate for allogeneic SCT. Referral to a transplant center and early exploration of donor options in the appropriate patient is therefore paramount, given the potential narrow window of disease control. It is important to recognize that state of disease at time of SCT strongly correlates with outcome.8,9 Transplant outcomes are improved in patients who are in a morphologic remission and a minimal residual disease (MRD)-negative state.23 Although there is evidence that patients who proceed to transplant with untreated relapse can achieve a CR and enjoy long-term disease-free survival,6,24 our practice is to attempt to attain a morphologic remission (preferably MRD negative) with salvage therapy and proceed to SCT at that time.

Most patients with newly diagnosed ALL likely receive either a Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster–like regimen (containing asparaginase, vincristine, anthracyclines, and steroids) or hyper-CVAD (alternating cycles of cyclophosphamide, steroids, vincristine, and anthracycline with cycles of high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine). Maintenance with both regimens involves monthly cycles of prednisone, vincristine, methotrexate, and mercaptopurine for those patients who do not proceed to allogeneic transplant in first remission and includes IT prophylaxis. If relapse happens >1 year after initial induction, we consider retreating with the same regimen that was previously successful; otherwise, an alternative regimen is considered more appropriate. Reevaluating for CNS and testicular involvement at time of systemic relapse is critical. It is our practice to reinitiate CNS prophylaxis with IT chemotherapy at time of systemic relapse.

There have been multiple regimens explored specifically in adults with relapsed ALL, but none has emerged as a standard of care (Table 1).25-42 Caution should be used in comparing outcomes across these reports, because patient characteristics (including age, duration of first remission, and treatment at first or subsequent relapse) are quite variable. Some salvage regimens combine high-dose cytarabine with an anthracycline, with response rates of 23% to 55%.25-29 A regimen of high-dose cytarabine and fludarabine followed by G-CSF (FLAG), either alone or in combination with idarubicin (FLAG-IDA) yields response rates of 39% to 83% in the relapsed and refractory setting.30-32 Consideration of an asparaginase-containing salvage regimen is given when the patient did not receive this drug as part of initial treatment. Hyper-CVAD, either with or without augmentation with asparaginase, yields remission rates of 44% to 47% in the salvage setting.33,34 Other regimens involve various combinations of anthracyclines, low-dose cytarabine, asparaginase, and methotrexate, with remission rates ranging from 58% to 74%.35,36 Clofarabine, a nucleoside analog approved for use in children with relapsed ALL, has a response rate of only 17% when used as a single agent in adults, prompting its use in combination.37 Responses to combination regimens (clofarabine/etoposide/mitoxantrone; clofarabine/cyclophosphamide; clofarabine/cytarabine) have ranged from 17% to 36%.38-40 Although there is reasonable chance of achieving a second CR (CR2) with these various regimens, the duration of remissions are short, with long-term survivors limited, in general, to those who are able to undergo an allogeneic SCT.6,9,25,26,31,33,40 Conventional agents are also being explored alone and in combination with other agents in the relapsed setting. Combination chemotherapy regimens may be improved with the introduction of additional conventional agents. For example, the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib has been shown in preclinical models to have synergy with standard ALL agents, including dexamethasone, vincristine, doxorubicin, asparaginase, and cytarabine. It has been evaluated as part of a combination salvage regimen in children and young adults, with a 73% overall response rate among 22 patients treated.43

Selection of salvage regimens used in relapsed/refractory adult Ph− ALL

| Chemotherapy . | Regimen . | Patients . | Results . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-dose cytarabine + anthracycline | Cytarabine: 3 g/m2 on days 1-5 Idarubicin: 40 mg/m2 on day 3 | N = 29 (age >15 y) n = 21 relapsed n = 8 refractory | CR = 38%; 14% to SCT; TRM = 3% | 26 |

| Cytarabine: 3 g/m2 on days 1-5 Idarubicin: 40 mg/m2 on day 3 | N = 135 (median age 30 y) Relapsed & refractory | CR = 55%; 40% to SCT; TRM = 12% | 25 | |

| Cytarabine: 3 g/m2 on days 1-5 Mitoxantrone: 80 mg/m2 on day 1 | N = 31 (age >16 y) No prior cytarabine | CR = 23%; 1 patient to SCT; TRM = 16% | 27 | |

| Cytarabine: 3 g/m2 on days 1-5 Mitoxantrone: 40-60 mg/m2 on day 1 | N = 11 | CR = 53%; TRM = 6% | 29 | |

| Cytarabine: 1 g/m2 every 12 h on days 1-5 Etoposide: 100 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Amsacrine 120 mg/m2 on days 1-3 | N = 40 All relapsed | CR = 40%; 10% to SCT | 28 | |

| FLAG-based | FLAG (1-2 cycles) Fludarabine: 30 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Cytarabine: 2 g/m2 on days 1-5 G-CSF | N=12 First relapse only | CR = 83%; TRM = 8% | 30 |

| FLAG-IDA (2 cycles) Fludarabine: 30 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Cytarabine: 2 g/m2 on days 1-5 Idarubicin: 10 mg/m2 on days 1-5 G-CSF | N=23 Relapsed/refractory | CR = 39%; 30% to SCT; TRM = 4% | 31 | |

| FLAG-IDA Fludarabine: 25 mg/m2 × 5 d Cytarabine 2 g/m2 × 5 d Idarubicin: 12 mg/m2 × 3 d G-CSF | N = 22 Relapsed/refractory | CR = 42% | 32 | |

| Hyper-CVAD–based | Hyper-CVAD (8 cycles alternating A and B) A: Cy, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone B: High-dose methotrexate and cytarabine | N = 66 n = 10 refractory n = 56 relapsed | CR = 44% | 34 |

| Augmented hyper-CVAD (8 cycles alternating A and B) Incorporates l-asparaginase* or peg-asparaginase and additional dexamethasone and vincristine doses into cycles | N = 88 (median age 34 y) n = 10 refractory n = 78 relapsed | CR = 47%; 32% to SCT; TRM = 9% | 33 | |

| Clofarabine-based | Clofarabine: 40 mg/m2 on days 1-5 | N = 12 (median age 54 y) Relapsed/refractory | CR = 17% | 37 |

| Clofarabine based (PETHEMA) n = 5 clofarabine alone n = 12 clofarabine + Cy n = 8 clofarabine + Cy + etoposide n = 6 clofarabine + cytarabine | N = 31 (median age 33 y) Relapsed/refractory Heavily pretreated | CR = 31%; 19% to SCT; TRM = 23% | 40 | |

| Clofarabine: 40 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Cytarabine: 1 g/m2 on days 1-5 | N = 37 (median age 41 y) Relapsed/refractory | CR = 17%; 21% to SCT; TRM = 19% | 39 | |

| Clofarabine: 20-25 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Etoposide: 100 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Mitoxantrone: 8 mg/m2 on days 1-3 | N = 4 Relapsed/refractory | CR = 50% (ALL); TRM = 9% (AML & ALL) | 38 | |

| Other combinations | Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster–like | N = 50 (age 18-53 y) | 58% CR | 35 |

| Mitoxantrone: 8 mg/m2 × 3 Etoposide: 100 mg/m2 × 5 Ifosfamide: 1.5 g /m2 × 5 | N = 11 | CR = 73% | 41 | |

| 5-Day induction vindesine, mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, methotrexate, prednisolone | N = 45 n = 17 refractory n = 28 relapsed | CR = 74%; 31% to SCT; TRM = 4% | 36 | |

| Liposomal vincristine | Liposomal vincristine: 2.25 mg/m2 weekly | N = 65 Relapsed Heavily pretreated | CR = 20%; PR = 15%; 19% to SCT | 16 |

| Nelarabine | Nelarabine: 1.5 g/m2 on days 1, 3, 5 | N = 26 (aged 16-64 y) T-cell ALL No CNS disease | CR = 31%; PR = 10% | 15 |

| Nelarabine: 1.5 g/m2 on days 1, 3, 5 | N = 126 (aged 18-81 y) T-cell ALL Relapsed/refractory | CR = 36%; PR = 10%; 29% to SCT; TRM ≤1% | 42 |

| Chemotherapy . | Regimen . | Patients . | Results . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-dose cytarabine + anthracycline | Cytarabine: 3 g/m2 on days 1-5 Idarubicin: 40 mg/m2 on day 3 | N = 29 (age >15 y) n = 21 relapsed n = 8 refractory | CR = 38%; 14% to SCT; TRM = 3% | 26 |

| Cytarabine: 3 g/m2 on days 1-5 Idarubicin: 40 mg/m2 on day 3 | N = 135 (median age 30 y) Relapsed & refractory | CR = 55%; 40% to SCT; TRM = 12% | 25 | |

| Cytarabine: 3 g/m2 on days 1-5 Mitoxantrone: 80 mg/m2 on day 1 | N = 31 (age >16 y) No prior cytarabine | CR = 23%; 1 patient to SCT; TRM = 16% | 27 | |

| Cytarabine: 3 g/m2 on days 1-5 Mitoxantrone: 40-60 mg/m2 on day 1 | N = 11 | CR = 53%; TRM = 6% | 29 | |

| Cytarabine: 1 g/m2 every 12 h on days 1-5 Etoposide: 100 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Amsacrine 120 mg/m2 on days 1-3 | N = 40 All relapsed | CR = 40%; 10% to SCT | 28 | |

| FLAG-based | FLAG (1-2 cycles) Fludarabine: 30 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Cytarabine: 2 g/m2 on days 1-5 G-CSF | N=12 First relapse only | CR = 83%; TRM = 8% | 30 |

| FLAG-IDA (2 cycles) Fludarabine: 30 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Cytarabine: 2 g/m2 on days 1-5 Idarubicin: 10 mg/m2 on days 1-5 G-CSF | N=23 Relapsed/refractory | CR = 39%; 30% to SCT; TRM = 4% | 31 | |

| FLAG-IDA Fludarabine: 25 mg/m2 × 5 d Cytarabine 2 g/m2 × 5 d Idarubicin: 12 mg/m2 × 3 d G-CSF | N = 22 Relapsed/refractory | CR = 42% | 32 | |

| Hyper-CVAD–based | Hyper-CVAD (8 cycles alternating A and B) A: Cy, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone B: High-dose methotrexate and cytarabine | N = 66 n = 10 refractory n = 56 relapsed | CR = 44% | 34 |

| Augmented hyper-CVAD (8 cycles alternating A and B) Incorporates l-asparaginase* or peg-asparaginase and additional dexamethasone and vincristine doses into cycles | N = 88 (median age 34 y) n = 10 refractory n = 78 relapsed | CR = 47%; 32% to SCT; TRM = 9% | 33 | |

| Clofarabine-based | Clofarabine: 40 mg/m2 on days 1-5 | N = 12 (median age 54 y) Relapsed/refractory | CR = 17% | 37 |

| Clofarabine based (PETHEMA) n = 5 clofarabine alone n = 12 clofarabine + Cy n = 8 clofarabine + Cy + etoposide n = 6 clofarabine + cytarabine | N = 31 (median age 33 y) Relapsed/refractory Heavily pretreated | CR = 31%; 19% to SCT; TRM = 23% | 40 | |

| Clofarabine: 40 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Cytarabine: 1 g/m2 on days 1-5 | N = 37 (median age 41 y) Relapsed/refractory | CR = 17%; 21% to SCT; TRM = 19% | 39 | |

| Clofarabine: 20-25 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Etoposide: 100 mg/m2 on days 1-5 Mitoxantrone: 8 mg/m2 on days 1-3 | N = 4 Relapsed/refractory | CR = 50% (ALL); TRM = 9% (AML & ALL) | 38 | |

| Other combinations | Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster–like | N = 50 (age 18-53 y) | 58% CR | 35 |

| Mitoxantrone: 8 mg/m2 × 3 Etoposide: 100 mg/m2 × 5 Ifosfamide: 1.5 g /m2 × 5 | N = 11 | CR = 73% | 41 | |

| 5-Day induction vindesine, mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, methotrexate, prednisolone | N = 45 n = 17 refractory n = 28 relapsed | CR = 74%; 31% to SCT; TRM = 4% | 36 | |

| Liposomal vincristine | Liposomal vincristine: 2.25 mg/m2 weekly | N = 65 Relapsed Heavily pretreated | CR = 20%; PR = 15%; 19% to SCT | 16 |

| Nelarabine | Nelarabine: 1.5 g/m2 on days 1, 3, 5 | N = 26 (aged 16-64 y) T-cell ALL No CNS disease | CR = 31%; PR = 10% | 15 |

| Nelarabine: 1.5 g/m2 on days 1, 3, 5 | N = 126 (aged 18-81 y) T-cell ALL Relapsed/refractory | CR = 36%; PR = 10%; 29% to SCT; TRM ≤1% | 42 |

Cy, cyclophosphamide; FLAG, fludarabine/high-dose cytarabine/G-CSF; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IDA, idarubicin; PETHEMA, Programa Español de Tratamiento en Hematologia; PR, partial remission; TRM, treatment-related mortality.

l-asparaginase is not currently commercially available.

Given that patient 1 has T-cell disease, we can also consider the use of nelarabine (either alone or in combination with other agents) as a salvage therapeutic option. Nelarabine is a purine analog (prodrug of Ara-G) which is FDA approved to treat adults with T-cell ALL/lymphoblastic lymphoma which has relapsed or progressed after 2 prior chemotherapy regimens. This agent received accelerated approval in 2005 on the basis of a CR rate of 31% in 26 adult patients with relapsed or refractory disease to at least 1 multiagent chemotherapy regimen.15 Subsequently, a larger phase 2 study in Germany evaluated outcomes of 126 heavily pretreated relapsed or refractory adult patients (aged 18-81 years). A CR rate of 36% and a partial remission rate of 10% were observed, with 80% of patients who achieved CR treated with subsequent allogeneic SCT.42 Significant neurologic toxicity (7% grade 3-4) can occur with nelarabine and was the dose-limiting toxicity in phase 1 studies. As such, no subjects in either study had CNS disease. Given the success rate of nelarabine as a single agent, its use in combination with other therapies has been reported in the pediatric population.44,45 Preliminary results from a phase 1 study using nelarabine in combination with etoposide and cyclophosphamide for relapsed pediatric patients showed an overall response rate of 44%.45

Patient 1 continued.

N.J. was treated with nelarabine/cyclophosphamide/etoposide combination chemotherapy while a donor search was initiated. Unfortunately, she had progressive disease after her second cycle of this therapy.

Our initial salvage choice given her T-cell immunophenotype and lack of CNS disease or neuropathy was a nelarabine-based regimen. This failed to induce a remission. We then chose a regimen containing peg-asparaginase, but unfortunately, she had persistent disease and cytopenias and died of an infectious complication.

Patient 2

H.T. presented with Ph− B-cell ALL at age 48 years. Assessment for CNS disease at diagnosis was negative. She received induction via the Larson regimen (daunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, cyclophosphamide,l-asparaginase) and achieved a CR. She completed subsequent cycles of consolidation and intensification with appropriate CNS prophylaxis and started therapy with vincristine, prednisone, mercaptopurine, and methotrexate maintenance. Two years after initiating treatment, while still undergoing maintenance, she developed headaches. A lumbar puncture was performed that confirmed CNS disease. Neurologic examination was normal. Bone marrow biopsy and aspirate samples at this time showed morphologic remission. How should this patient be treated?

The CNS is a common site of disease involvement for patients with ALL and is also a sanctuary site not penetrable by most chemotherapeutic agents. Although the routine administration of CNS prophylaxis (which includes combinations of IT antimetabolites, cranial radiotherapy, and systemic chemotherapy with drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier) has improved overall outcome and significantly decreased the risk of CNS disease, 2% to 15% of patients will have CNS involvement at time of relapse.46-50 In a study of 467 adult patients treated with an initial regimen that included IT cytarabine, methotrexate, and hydrocortisone in conjunction with systemic high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine, 159 patients eventually relapsed. Of these, 22 (5.8%) had CNS involvement at time of relapse, of which 14 cases were isolated to the CNS.48 Recurrence of CNS disease is often associated with a systemic relapse, and a restaging bone marrow biopsy and aspirate, preferably with an assessment for MRD, should always be performed. Even when a CNS relapse appears to be isolated, it often is a harbinger for subsequent systemic relapse.46 For this reason, systemic chemotherapy is recommended as part of the management for patients with seemingly isolated CNS disease. Of importance, the only 2 long-term survivors in the cohort with CNS relapse mentioned above obtained remission with combined IT and systemic chemotherapy and went on to an allogeneic SCT in CR2.48 For patient 2, we initiated a donor search while treating her relapsed disease.

Systemic therapy with high-dose methotrexate and/or cytarabine (included as part of this patient’s treatment plan) is attractive because these agents also cross the blood-brain barrier. The CNS can also be targeted using IT antimetabolites and cranial or craniospinal radiation. Some patients may have been exposed to radiation as part of their upfront therapy and this may limit its role in the salvage setting. It is our practice in a patient such as this (who presents with blasts in the cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] and a normal neurologic examination) to start with an IT chemotherapy approach incorporating alternating doses of IT cytarabine and methotrexate. IT therapy is given twice weekly until clearance of blasts, then weekly for several weeks. Liposomal cytarabine can also be considered and has been shown to be efficacious with acceptable toxicity (when given adjunctively with dexamethasone) in patients with CNS relapse.51 Its delayed release formulation offers the benefits of less frequent administrations (every 2 weeks) and more even distribution of drug in CSF. We reserve radiation for IT failure or for patients with cranial nerve involvement. In scheduling cranial radiation, care would need to be taken to distance from both IT and systemic methotrexate to minimize toxicity. Choices for delivery of IT chemotherapy include serial lumbar punctures or the placement of an Ommaya reservoir. Ommaya reservoirs are placed either for patient comfort or based on the theory that better distribution of drug can be obtained through direct delivery into the ventricular space, resulting in improved efficacy.52

Patient 2 continued.

H.T. tolerated lumbar puncture poorly and an Ommaya reservoir was placed. She started therapy with IT methotrexate alternating with IT cytarabine, with resolution of her headaches and clearance of her CSF. She received 2 cycles of systemic therapy with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine and was referred for consideration of allogeneic SCT while in CR2. Unfortunately, a restaging bone marrow biopsy prior to admission for SCT was positive for low-level disease (3% blasts by morphology). Her systemic disease progressed despite a third cycle of chemotherapy (which she tolerated poorly), and she developed double vision associated with an oculomotor nerve palsy. Assessment of CSF at this time was negative. She received cranial radiation and her oculomotor nerve palsy resolved; however, she had progression of her systemic disease.

Chemotherapy choices are now very limited in this patient. Subsequent attempts at salvage therapy after first relapse confer a decreasing chance of disease control, likely reflective of the chemotherapy-resistant nature of the disease.9 In addition, her ability to tolerate most combination regimens is diminishing. In an attempt to control her systemic disease, we initiated therapy with liposomal vincristine.

Liposome vincristine was developed with the goal of increasing drug exposure of vincristine to neoplastic cells while minimizing dose-limiting neurotoxicity. It is FDA approved for the treatment of adult patients with Ph− ALL in second or greater relapse. This indication is based on the overall response rate in relapsed patients, because improvement in overall survival has not been verified.16 In a phase 2 trial, 65 adults with heavily pretreated B- and T-cell ALL were treated with weekly doses of liposomal vincristine at 2.25 mg/m2. All patients had received prior vincristine. There was a 32% overall response rate (CR, CR with incomplete hematologic recovery, and partial remission), with a median duration of response of 23 weeks (range 5-66 weeks) and median overall survival of 4.6 months. Of the complete responders, 67% achieved an MRD-negative state, which correlated with longer survival, and 19% were bridged to allogeneic SCT.16 Twenty-three percent of patients developed grade 3 neuropathy and 1 patient developed grade 4 neuropathy, but the therapy was otherwise well tolerated.

Our patient received liposomal vincristine, which she tolerated well, but unfortunately, she died with progressive refractory disease.

Patient 3

D.K. presented at age 21 years with pre–B-cell Ph− ALL without CNS involvement. He was treated with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD chemotherapy (alternating cycles of daunorubicin, prednisone, and vincristine with high doses of methotrexate and cytarabine) with prophylactic IT chemotherapy. He achieved a CR and, after 4 cycles of therapy, underwent a myeloablative allogeneic SCT from his HLA-identical brother using a cyclophosphamide/total body irradiation–based conditioning regimen. He had systemic relapse 13 months after SCT, 17 months after diagnosis. Assessment for CNS disease was negative. He underwent salvage chemotherapy with FLAG and did not achieve a remission. He then underwent a second salvage regimen with escalating doses of methotrexate in combination withl-asparaginase, vincristine, and dexamethasone, and achieved CR2 with a treatment-related complication of pancreatitis. He received donor leukocyte infusion (DLI) while in CR2 without induction of graft-versus-host disease. The patient then experienced a third systemic relapse 7 months after achieving CR2 and was referred to us for treatment options.

A graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect in ALL is presumed, because allogeneic transplant results in decreased relapse rates and increased cure rates compared to chemotherapy alone in adults with ALL.5 This GVL effect, however, is difficult to harness for the 25% of patients who will still relapse after an SCT performed in first remission. Reasons for this are unclear but may be related to the decreased ability of lymphoblasts (with low expression of T-cell co-stimulatory molecules) to present antigens, resulting in T-cell anergy.53 Prognosis for patients with relapse after SCT is therefore very poor, and there are only isolated reports of adults who become long-term survivors. The few patients that may ultimately be cured are younger patients whose relapse after first SCT occurs prior to the onset of the GVL effect (and without graft-versus-host disease) and may be salvaged with DLI or a second SCT from the same or a different donor.53,54

There is no standard approach for a patient with relapsed disease after SCT. Withdrawal of immune suppression and DLI (alone or after chemotherapy) results in response rates of 0% to 20%, which are usually short-lived.53,55-58 A second allogeneic SCT offers the rare patient the possibility of long-term survival but with significant potential cost in terms of treatment-related mortality, which may be lessened with a reduced-intensity approach.59,60 The optimal choice of donor (original or a second donor) and intensity of conditioning (myeloablative or reduced intensity) is not known. In general, if an appropriate candidate for a second SCT is identified, we attempt to induce remission and opt for an SCT from a second donor. It is also reasonable to consider a haploidentical transplant in this setting as an approach that relies on natural killer cell alloreactivity as a primary mediator of the GVL effect.53,61

In this young patient with delayed relapse after SCT, the initial approach was disease control with systemic chemotherapy followed by DLI. FLAG, containing fludarabine and high-dose cytarabine, was initially chosen but was not successful. A trial of a regimen containing l-asparaginase, which the patient was not exposed to during initial treatment, was successful in inducing a remission. It was anticipated that this remission with a chemotherapy-alone approach would be short-lived, and DLI was administered. As predicted in the discussion above, a long-term response to DLI was not achieved and the patient relapsed.

Blinatumomab, a bispecific antibody that redirects cytotoxic T cells to B cells with its anti-CD3 and anti-CD19 arms, has emerged as an effective approach for patients with B-cell disease. Blinatumomab was first explored in patients in first morphologic remission with MRD-positive ALL, and successfully converted the majority of patients to an MRD-negative state.62,63 Follow-up studies in patients with relapsed and refractory Ph− B-cell ALL have been very promising, leading to the drug’s accelerated approval by the FDA on December 3, 2014.17,64 A multicenter, single-arm study treated 189 adult patients with relapsed or refractory Ph− B-cell ALL with single-agent blinatumomab. Sixty-four of these subjects (such as patient 3) had relapsed after a prior allogeneic SCT. Blinatumomab was administered as a 28-day continuous infusion (9 μg/d for days 1-7; 28 μg/d thereafter), followed by 2 weeks of rest for up to 5 cycles. CR and CR without full hematologic recovery occurred in 43% of patients within the first 2 cycles. Of note, 82% of these patients were also MRD negative as determined by allele-specific quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Of responding patients without prior SCT, 40% were bridged successfully to SCT.17 Durable remissions were dependent on subsequent allogeneic SCT, with a median overall survival of 6.1 months. Observed treatment-related adverse events with blinatumomab usually occur in the first cycle and include fever, cytokine release syndrome, and neurologic toxicity.17,64,65 As such, it is contraindicated in patients with evidence of CNS disease.

Patient 3 continued.

At the time of his third relapse, D.K. was treated with blinatumomab, which at that time was available only on clinical trial (he likely would have received it earlier had it been available). He achieved a complete morphologic remission and was MRD negative 1 month after starting this therapy. Unfortunately, while undergoing a workup for a second transplant from a matched unrelated donor, he relapsed 3 months after obtaining a third CR and is pursuing additional clinical trial options.

The horizon

Unfortunately, most patients with relapsed ALL will have chemotherapy-resistant disease, which drives the pursuit of therapies with alternative mechanisms of action. As described earlier, the recent FDA approval of blinatumomab highlights the rapidly emerging role of antibody-directed therapy in the management of ALL. Clinical trials using genetically modified T cells targeted to CD19 have also been very promising. Further understanding of the biology of the disease (such as characterization of Ph-like B-cell ALL and Notch-1 mutations in T-cell ALL) and (it is hoped) parallel advances in performing gene expression and molecular profiling for more patients will lead to a change in our treatment paradigm over time. Another important consideration is that many of these exciting advances and therapeutic options currently used in the salvage setting may be incorporated eventually into the upfront setting.

Antibody therapy

Antigens expressed on ALL cells (CD19, CD20, CD22, and CD52) have proved to be appropriate targets for monoclonal antibodies either alone or in combination with traditional chemotherapy.65-68 Rituximab, an unconjugated chimeric human-mouse monoclonal antibody targeted to CD20, has dramatically changed outcomes for patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and has launched an ever-expanding field of chemoimmunotherapy.69 Its potential synergistic role when combined with standard upfront chemotherapy in adult patients with CD20-positive ALL has been explored, with more rapid achievement of MRD negativity and improved long-term survival observed in younger Ph− adults (<60 years old) when combined with the hyper-CVAD regimen.70 Ofatumumab, a fully humanized anti-CD20 antibody that binds a different epitope than rituximab, is also being explored in the upfront setting, with promising preliminary results. Consideration of employing anti-CD20–directed therapy as part of a salvage regimen for CD20-positive ALL is reasonable, although it should be noted that the benefit in the relapsed setting has not been proved. Alemtuzumab, a humanized monoclonal anti-CD52 antibody, has shown promising results, with reduction of MRD when combined as part of upfront postremission therapy.68

CD22 is another attractive target because it is expressed on >90% of pre–B-cell ALL. Epratuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting CD22 that is internalized after binding its target. It has been explored in combination with clofarabine and high-dose cytarabine in 36 adult patients with relapsed disease, resulting in a response rate of 52% (Southwestern Oncology Group S0910)71 compared to a 17% response rate observed in a prior study using clofarabine and cytarabine alone.39 Further exploration of 90Y-epratuzumab tetraxetan as radioimmunotherapy is underway, with a CR observed in 1 patient.72 Inotuzumab ozogamicin, another CD22 monoclonal antibody, is bound to calicheamicin and induces apoptotic cell death after internalization. It has shown efficacy as a single agent with a tolerable toxicity profile in heavily pretreated relapsed and refractory patients. In a phase 1/2 trial using single-agent inotuzumab ozogamicin, the overall response rate was 57%. It was noted, however, that venoocclusive disease developed in 5 of 22 patients who went to allogeneic SCT.73 Other CD22-directed antibodies, such as moxetumomab pasudotox, are in clinical development.74

CAR T cells

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) have been engineered and introduced into immune effector cells, redirecting them to target specific tumor antigens, including CD19.75 This novel cellular therapeutic approach is now being developed by several programs to target CD19-positive malignancies, including pediatric and adult ALL. Complete remission rates >80% have been observed, and patients have been successfully bridged to SCT with this approach.18,20,76 Excitingly, some remissions have been remarkably durable without a consolidative SCT, a finding that correlates with in vivo T-cell persistence and B-cell aplasia over time.20 The major treatment-related toxicity that has emerged from CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy is cytokine release syndrome, which manifests with fever and malaise but can progress to capillary leak and hypotension, with some affected patients requiring intensive care unit–level support. It is associated with rapid in vivo T-cell activation and expansion and can usually be reversed with anticytokine-directed therapy.18,76 Similar to toxicities seen with blinatumomab, neurologic events are also observed with this approach, and T cells have been observed in the CSF of treated patients.18,77 Clinical trials are ongoing using this approach, and additional targets (such as CD22) are being explored.

Ph-like ALL

Ph-like ALL is a subtype of precursor B-cell ALL that carries a poor prognosis and a similar gene expression profile to bcr-abl–positive ALL.78 It has recently been recognized that the proportion of ALL patients with a Ph-like phenotype peaks in adolescents and young adults. Among patients with precursor B-cell ALL, 12% of children, 20% of adolescents, and 27% of young adults (aged 20-39 years) are affected, with the incidence dropping sharply in older adults.78,79 Multiple kinase-activating mutations in Ph-like ALL have been identified, with preclinical data suggesting successful potential therapeutic targeting with kinase inhibitors such as dasatinib, ruxolitinib, and crizotonib.78,80

T-cell ALL can also be characterized by its gene expression profiles, leading to promise for targeted therapeutics for this disease in both the upfront or relapsed settings.81-85 Flt3 mutations have been identified in adult early T-cell precursor ALL, suggesting an opportunity to explore the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in this disease.84,85 Notch1 and bcl-2 inhibitors are other examples with exiting preclinical data suggesting potential efficacy in the clinical realm for T-cell disease.83,86,87 Preliminary results from a phase 1 clinical trial using a γ-secretase inhibitor with anti-notch activity (BMS-906024) showed clinical activity as a single agent.87 Clinical trials are ongoing with these agents.

Authorship

Contribution: N.V.F and S.M.L wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.V.F. has research support from Novartis. S.M.L has received honoraria from Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Novartis.

Correspondence: Selina Luger, Abramson Cancer Center, Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine 2 South, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: selina.luger@uphs.upenn.edu.