Key Points

Inactivation of PLZF promotes phenotype of HSC aging.

PLZF controls HSC cell cycle.

Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) give rise to all blood populations due to their long-term self-renewal and multipotent differentiation capacities. Because they have to persist throughout an organism’s life span, HSCs tightly regulate the balance between proliferation and quiescence. Here, we investigated the role of the transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (plzf) in HSC fate using the Zbtb16lu/lu mouse model, which harbors a natural spontaneous mutation that inactivates plzf. Regenerative stress revealed that Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs had a lineage-skewing potential from lymphopoiesis toward myelopoiesis, an increase in the long-term-HSC pool, and a decreased repopulation potential. Furthermore, old plzf-mutant HSCs present an amplified aging phenotype, suggesting that plzf controls age-related pathway. We found that Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs harbor a transcriptional signature associated with a loss of stemness and cell cycle deregulation. Lastly, cell cycle analyses revealed an important role for plzf in the regulation of the G1-S transition of HSCs. Our study reveals a new role for plzf in regulating HSC function that is linked to cell cycle regulation, and positions plzf as a key player in controlling HSC homeostasis.

Introduction

Stem cells are maintained in a body for a long period and have developed specific programs against a variety of physiological stresses in order to maintain their lifelong integrity. As with most tissues that have a high cellular turnover, hematopoietic tissue is sensitive to aging, which results in multiple functional defects that accumulate in HSCs from older individuals.1 Aging HSCs have a reduction in their regenerative capacity and support decreased lymphoid lineage output together with increased myeloid output.2,3 Surprisingly, the number of phenotypically defined HSCs increases with age; although it has long been known that aging has a major impact on the frequency and cell cycle kinetics of hematopoietic cell compartments,4 mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain poorly understood.

The transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF), also known as Zbtb16, was first described as a transcriptional repressor rearranged in cases of acute promyelocytic leukemias associated with the t(11;17) translocation.5 Since then, PLZF has been shown to be involved in major developmental and biological processes such as spermatogenesis, hind limb formation, and hematopoiesis regulation,6 with versatile biological function7 regulated by posttranslational modifications8 and/or differential epigenetic cofactor recruitment.9-11 Within the hematopoietic system, PLZF has essential roles in the maintenance and development of multiple hematopoietic cells12-14 and is emerging as an important regulator of innate immune cell function by restraining inflammatory signaling programs.15

Published data indirectly suggest that PLZF could be an important regulator of the HSC, although a direct demonstration is still lacking. To this end, we studied the role of the transcription factor PLZF in the regulation of HSC fate.

Study design

Mouse models, cell sorting, and transplantation

C57BL/6-CD45.1 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. B6-CD45.1/CD45.2 mice were bred in the Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie de Marseille mouse facility. Zbtb16lu/lu C57BL/6-CD45.2 mice were derived from frozen Zbtb16wt/lu embryos purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The strategy and the antibody combination are presented, respectively, in supplemental Figure 1 and supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site. Flow cytometry analyses were performed using a BD-LSRII cytometer and analyzed using BD-DIVA Version 6.1.2 software (Special Order Research Products; BD Biosciences). Lineage-negative (Lin−) cells were enriched using the Lineage Cell Depletion Kit (Miltenyi Biotec), and cell sorting was performed on a FACS AriaII (Special Order Research Products; BD Biosciences). For serial transplantation assays, 2 × 106 total bone marrow (BM) cells were isolated from Zbtb16lu/lu or wild-type (WT) littermates (C57BL/6-CD45.2) and transplanted IV into 6- to 8-week-old recipient mice (C57BL/6-CD45.1), lethally irradiated (8 Gy using the RS 2000 X-ray irradiator; Rad Source Technologies). For competitive transplantation assays, 1 × 106 total BM cells of 8-week-old Zbtb16lu/lu or 1-year-old WT mice (C57BL/6-CD45.2) were mixed with 1 × 106 total competitor CD45.1/2 BM cells and injected IV.

Cell cycle analysis and apoptosis

Zbtb16lu/lu and WT Lin− fractions were stained for HSCs (Lin−/Sca+/Kit+, Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3, CD150+) and subsequently incubated with Ki-67 and 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole. For 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) analysis, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 3 mg of BrdU 18 hours before isolating BM cells. BM Lin− cells were stained for HSCs, and phases of cell cycle were analyzed by measuring the incorporation of BrdU and 7-aminoactinomycin D using the FITC BrdU Flow Kit (BD Pharmingen). For myelosuppression induction, Zbtb16lu/lu and WT mice were injected intraperitoneally with a single dose of 5-fluorouracil at a concentration of 150 mg/kg 5 days before BrdU injection. Apoptosis was measured with Annexin V (BD Pharmingen).

Gene expression profiling

DNA microarrays were used to define and compare the transcriptional profiles of LSK cells isolated from Zbtb16lu/lu mice and WT mice (n = 4). For details, see also supplemental Experimental Procedures. Raw transcriptomic data were deposited in ArrayExpress database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/; accession number: E-MTAB-3682).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests.

Results and discussion

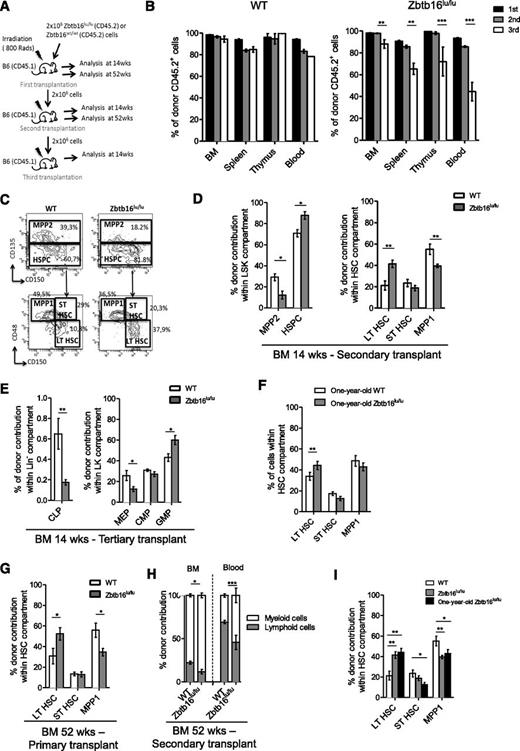

To elucidate PLZF function in hematopoietic development, we analyzed the hematopoietic compartment of the Zbtb16lu/lu mouse model.16 Zbtb16lu/lu mice showed a twofold BM cellularity reduction (supplemental Figure 2A) due to their reduced size,16 but no difference was observed in the relative numbers of mature cells, phenotypically defined progenitors, or HSCs in comparison with WT BM, with the exception of the relative number of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs), which was slightly increased in Zbtb16lu/lu mice (supplemental Figure 2B-H). Because we revealed a reduction in Zbtb16lu/lu HSC colony formation (supplemental Figure 3), which was in accordance with the loss of transforming potential observed in plzf-mutant HSCs,17 we assessed the functional competence of Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs by serial transplantation assay (Figure 1A). This assay revealed a defect of Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs to reconstitute hematopoietic organs after 3 successive transplants (Figure 1B). To better understand this functional defect, we analyzed Zbtb16lu/lu HSC populations after 14 and 52 weeks of reconstitution. When analyzing the Zbtb16lu/lu HSC pool at 14 weeks, we observed an increased frequency of immature LT-HSCs at the expense of the MPP1 fraction (Figure 1C-D; supplemental Figure 4A) in secondary and tertiary recipients. When frequency was converted to absolute number, a significant accumulation of LT-HSCs was observed in the BM of secondary Zbtb16lu/lu recipients (supplemental Figure 4B). In addition, we observed a compromised reconstitution of common lymphoid progenitors, whereas GMPs were increased in tertiary recipients of Zbtb16lu/lu BM (Figure 1E), resulting in a loss of B cells in favor of myeloid cells in peripheral blood, BM, and spleen of the Zbtb16lu/lu tertiary reconstituted mice (supplemental Figure 4C). These results suggest that plzf mutation alters HSC functions through increasing the LT-HSC pool and by biasing the HSC differentiation potential toward the myeloid compartment. Because these features are characteristics of aged HSCs,1,3,18 we further investigated Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs upon aging. First, we analyzed the HSC compartment of 1-year-old Zbtb16lu/lu mice and revealed that among the HSC population, LT-HSCs were significantly more expanded in aged Zbtb16lu/lu mice compared with WT mice (Figure 1F). In addition, 1-year-old Zbtb16lu/lu transplanted mice harbored an accelerated age–like phenotype, because the 2 aging characteristics were observed 1 transplant earlier when mice were analyzed at 52 rather than at 14 weeks after transplant (Figure 1G-H). We further compared young Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs with 1-year-old HSCs for their competitive repopulation ability. Although old HSCs have a decreased regenerative potential, they keep a myeloid competitive advantage after the first transplant.1 We showed that for 1-year-old HSCs, the Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs have a myeloid competitive advantage (supplemental Figure 5) and contribute more to the LT-HSC compartment relative to the ST-HSC and MPP1 fractions (Figure 1I). Together, these results suggest that Zbtb16lu/lu promotes a premature aging–like syndrome in mice after regenerative stress and imply a role for plzf in the control of age-related mechanisms in HSCs.

Zbt16lu/lu HSCs present defects associated with aged HSCs. (A) Serial transplantation assay. Donor BM CD45.2 Zbtb16lu/lu or WT cells were injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice and were serially transplanted. Analyses were performed at 14 weeks or at 52 weeks after transplant. (B) Analysis of CD45.2+ donor cells in BM, spleen, thymus, and blood 14 weeks after each transplant. Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses (C) and quantitative and statistical analyses (D) of long-term reconstitution in LSK and stem cell compartments 14 weeks after secondary transplant. (E) Quantitative analysis of long-term reconstitution in progenitor cell compartment 14 weeks after tertiary transplant. (F) Quantitative analysis of the HSC compartment in 1-year-old Zbtb16lu/lu and WT mice. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 5). (G-H) Analysis of hematopoietic compartments 1 year after primary and secondary transplants. (G) Percentage of LT-HSC, ST-HSC, and MPP1 fractions among CD45.2+ HSCs 1 year after primary transplant. (H) Distribution of CD45.2+ myeloid and CD45.2+ B cells in BM and peripheral blood 1 year after secondary transplant. For 14-week post-reconstitution bar graphs, data represent mean ± SEM. Data are based on 2 (primary, secondary, and tertiary transplants) experimental repeats, with 6 recipient mice per group (n = 12). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. For 52-week post-reconstitution bar graphs, data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). *P < .05; **P < .01. (I) Competitive reconstitution analysis. Donor CD45.2 young Zbtb16lu/lu or WT aged BM cells were transplanted with an equal number of CD45.1/2 competitor WT BM cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients. Quantitative and statistical analyses of long-term reconstitution in stem cell compartments 21 weeks after transplant. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 6). CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; LT, long-term; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor cells; MPP, multipotent progenitor; SEM, standard error of the mean; ST, short-term; wks, weeks.

Zbt16lu/lu HSCs present defects associated with aged HSCs. (A) Serial transplantation assay. Donor BM CD45.2 Zbtb16lu/lu or WT cells were injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice and were serially transplanted. Analyses were performed at 14 weeks or at 52 weeks after transplant. (B) Analysis of CD45.2+ donor cells in BM, spleen, thymus, and blood 14 weeks after each transplant. Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses (C) and quantitative and statistical analyses (D) of long-term reconstitution in LSK and stem cell compartments 14 weeks after secondary transplant. (E) Quantitative analysis of long-term reconstitution in progenitor cell compartment 14 weeks after tertiary transplant. (F) Quantitative analysis of the HSC compartment in 1-year-old Zbtb16lu/lu and WT mice. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 5). (G-H) Analysis of hematopoietic compartments 1 year after primary and secondary transplants. (G) Percentage of LT-HSC, ST-HSC, and MPP1 fractions among CD45.2+ HSCs 1 year after primary transplant. (H) Distribution of CD45.2+ myeloid and CD45.2+ B cells in BM and peripheral blood 1 year after secondary transplant. For 14-week post-reconstitution bar graphs, data represent mean ± SEM. Data are based on 2 (primary, secondary, and tertiary transplants) experimental repeats, with 6 recipient mice per group (n = 12). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. For 52-week post-reconstitution bar graphs, data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). *P < .05; **P < .01. (I) Competitive reconstitution analysis. Donor CD45.2 young Zbtb16lu/lu or WT aged BM cells were transplanted with an equal number of CD45.1/2 competitor WT BM cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients. Quantitative and statistical analyses of long-term reconstitution in stem cell compartments 21 weeks after transplant. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 6). CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; LT, long-term; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor cells; MPP, multipotent progenitor; SEM, standard error of the mean; ST, short-term; wks, weeks.

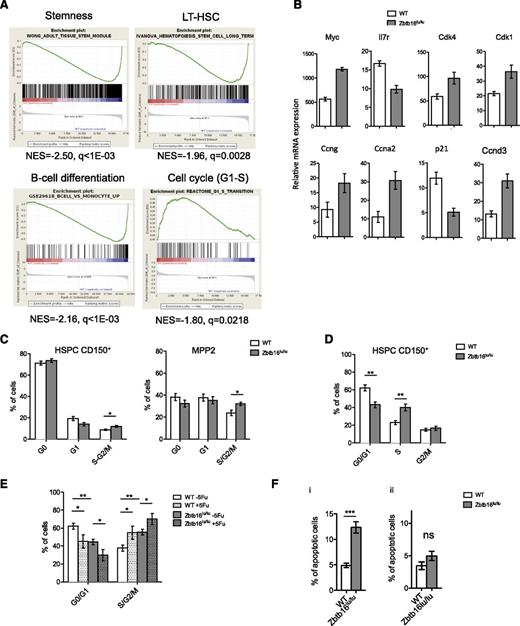

Comparative microarray-based gene expression data from Zbtb16lu/lu and control HSCs identified 1428 genes differentially expressed (supplemental Table 2). Gene ontology enriched terms associated with the genes upregulated in the Zbtb16lu/lu group included metabolic- and cell cycle–related processes, whereas gene ontology terms associated with downregulated genes were mainly involved in lymphoid functions (supplemental Table 3). Consistently, gene set enrichment analysis demonstrated a negative correlation between stemness and lymphoid signatures and a positive correlation between cell cycle signatures (in particular, genes involved in G1-S transition) and the Zbtb16lu/lu genotype (Figure 2A), suggesting changes in HSC cell cycles induced by plzf mutation. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis confirmed that Zbtb16lu/lu LT-HSCs presented a deregulated cell cycle gene expression profile (Figure 2B), important for HSC integrity.19

Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs shows cell cycle deregulation. HSCs from Zbtb16lu/lu and WT mice were subjected to gene expression analysis. (A) Gene set enrichment analysis of Zbtb16lu/lu LSKs compared with WT LSKs. (B) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of cell cycle–related gene expression in Zbtb16lu/lu and WT LT-HSCs sorted from young mice. Results are presented as relative to messenger RNA (mRNA) expression level. (C) Distribution of the CD150+ HSPC (left) and MPP2 cell fractions in G0, G1, and S-G2/M phases. Bars represent average ± SEM. Data were collected over 3 independent experiments (n = 7). (D) Distribution of Zbtb16lu/lu and WT CD150+ HSPCs in G1, S, and G2/M phases after BrdU injection. Bars represent average ± SEM. Data were collected over 2 independent experiments (n = 7). (E) Cell cycle analysis of Zbtb16lu/lu and WT CD150+ HSPCs 6 days after myelosupression obtained by a single dose of 5-fluorouracil (5Fu; 150 mg/kg) (n = 5). Bars represent average ± SEM. Data were collected over 2 independent experiments (n = 5). (F) Analysis of apoptosis in Zbtb16lu/lu and WT CD150+ HSPCs from 8- to 10-week-old mice (i) and from transplanted mice with 8- to 10-week-old BM (ii). Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 5). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .01. ns, not significant.

Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs shows cell cycle deregulation. HSCs from Zbtb16lu/lu and WT mice were subjected to gene expression analysis. (A) Gene set enrichment analysis of Zbtb16lu/lu LSKs compared with WT LSKs. (B) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of cell cycle–related gene expression in Zbtb16lu/lu and WT LT-HSCs sorted from young mice. Results are presented as relative to messenger RNA (mRNA) expression level. (C) Distribution of the CD150+ HSPC (left) and MPP2 cell fractions in G0, G1, and S-G2/M phases. Bars represent average ± SEM. Data were collected over 3 independent experiments (n = 7). (D) Distribution of Zbtb16lu/lu and WT CD150+ HSPCs in G1, S, and G2/M phases after BrdU injection. Bars represent average ± SEM. Data were collected over 2 independent experiments (n = 7). (E) Cell cycle analysis of Zbtb16lu/lu and WT CD150+ HSPCs 6 days after myelosupression obtained by a single dose of 5-fluorouracil (5Fu; 150 mg/kg) (n = 5). Bars represent average ± SEM. Data were collected over 2 independent experiments (n = 5). (F) Analysis of apoptosis in Zbtb16lu/lu and WT CD150+ HSPCs from 8- to 10-week-old mice (i) and from transplanted mice with 8- to 10-week-old BM (ii). Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 5). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .01. ns, not significant.

Next, we focused on the effect of the Zbtb16lu/lu mutation in HSC cell cycle regulation. Staining BM with Ki-67/4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole showed a decreased proportion of the Zbtb16lu/lu CD150+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in G1 phase, with an increased proportion of the cells in S-G2/M phase (Figure 2C). Measurement of BrdU incorporation 18 hours after injection coupled with 7-aminoactinomycin D staining demonstrated an accumulation of the Zbtb16lu/lu CD150+ HSPCs in S phase, a phenotype that was in accordance with previous observations of PLZF controlling G1/S and G2/M checkpoints of the cell cycle20,21 (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 6). This accumulation was even stronger after hematopoietic recovery induced by myelosuppression (Figure 2E). Considering that increased apoptosis upon plzf deletion was previously observed in the germ line in association with increased proliferation and tubule degeneration,16,22 we measured the level of apoptosis in Zbtb16lu/lu CD150+ HSPCs. We demonstrated a significant increase in apoptosis in Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs in comparison with WT cells (Figure 2Fi) that could account for the limited accumulation of Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs in young plzf-mutant mice. Interestingly, apoptosis was not as increased in transplanted Zbtb16lu/lu HSCs, a condition in which HSCs accumulate (Figure 2Fii). Although, we have no direct evidence that the Zbtb16lu/lu-induced cell cycle deregulation is linked to aging, especially considering recent studies reporting inconsistent cell cycle changes upon aging,23,24 our results support the links among plzf function, cell cycle regulation, and HSC integrity. Because epigenetic processes are known to regulate age-dependent functional changes,25,26 it will be important to study the epigenetic cofactors of plzf that have the ability to regulate cell cycle gene expression during aging.

The data reported in this article have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database (accession number E-MTAB-3682).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. L. Thibult and F. Mallet for assistance with the use of the cytometry and cell sorting facility; F. Bardin, R. Castellano, and L. Pouyet for help with irradiated mice injections; J. C. Orsoni and P. Gibier for assistance in the animal facility; and A. Saurin and C. Chabannon for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Fondation de France (201200029166), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale grant INE201000518534, the Fondation ARC pour la recherche sur le cancer, the Cancéropôle Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (C.V.-F.), the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (A.V.), and Institut Thématique Multi-Organismes Cancer (M.P.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.V.-F. designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and cowrote the paper; N.P., A.V., M.P., M.K., and A.-M.I. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; P.F., G.T., and F.B. performed the transcriptome analysis; E.D. initiated and directed the project and cowrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Estelle Duprez, INSERM U1068, Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie de Marseille, BP 30059, 27, Blvd Lei Roure, 13273 Marseille Cedex 09, France; e-mail: estelle.duprez@inserm.fr.

References

Author notes

N.P. and A.V. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal