Abstract

A discordant lymphoma occurs where 2 distinct histologic subtypes coexist in at least 2 separate anatomic sites. Histologic discordance is most commonly observed between the bone marrow (BM) and lymph nodes (LNs), where typically aggressive lymphoma is found in a LN biopsy with indolent lymphoma in a BM biopsy. Although the diagnosis of discordance relied heavily on histopathology alone in the past, the availability of flow cytometry and molecular studies have aided the identification of this entity. The true prevalence and clinical ramifications of discordance remain controversial as available data are principally retrospective, and there is therefore little consensus to guide optimal management strategies. In this review, we examine the available literature on discordant lymphoma and its outcome, and discuss current therapeutic approaches. Future studies in discordant lymphoma should ideally focus on a large series of patients with adequate tissue samples and incorporate molecular analyses.

Introduction

Bone marrow involvement (BMI) at diagnosis is present in the majority of indolent B-cell lymphomas (BCLs), and in most studies is reported to occur in ∼10% to 15% of diffuse large BCL (DLBCL) cases.1,2 It is an important clinical test and performed even when the likelihood of involvement is low, as it may portend an inferior clinical outcome and impact therapy selection.3 Although in most cases where BMI occurs, histology is concordant among involved sites, “discordance” refers to those lymphoma cases where the histology is distinctly different between the bone marrow (BM) and other sites of involvement. It is important to distinguish “discordant” from “composite,” where the latter term refers to “lymphomas in which 2 or more distinct areas of different histology can be appreciated in a single lymph node (LN)” as opposed to these findings in separate anatomic sites as in the case of “discordance.”4,5 Concordant and discordant clonality will also be discussed here, but histologic discordance does not mandate concordant clonality. In discussing “discordant” lymphomas, it is also important to distinguish “discordance” from “transformation.” Transformed lymphomas are defined as indolent lymphoma cases that undergo histologic transformation into aggressive lymphoma (usually DLBCL) during the course of the disease. They include Richter transformation or Richter syndrome, which describes cases of chronic lymphocytic leukemia that transform into DLBCL or Hodgkin lymphoma.6,7

There is a paucity of published experience on the biology, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of discordant lymphomas, and data are mostly derived from single case reports and small retrospective studies.8-17 Consequently, the incidence, clinical behavior, and optimal therapeutic approach to discordant lymphomas remain controversial with little overall consensus. In this review, we analyze the published literature on discordant non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), with particular emphasis on DLBCL. The review of the literature was performed by a search of the medical literature using the PubMed database at www.pubmed.gov.

Diagnosis of discordant lymphoma

The diagnosis of discordant lymphoma is based on histologic appearances but is challenging for the pathologist because no minimal criteria to define discordance are rigorously established and/or uniformly used.1,18 Although morphology is the cornerstone of diagnosis, the immunophenotypic and molecular characteristics of the lymphoma subtype may be helpful in diagnosing discordance. Although BMI of any histologic type has been found in an estimated 11% to 33% of patients with aggressive BCLs, BMI with indolent NHL (discordance) has ranged from between 5% to 24% in the limited studies that have been performed (Table 1).1,2,4,19-22 Interestingly, in the post-rituximab era, the incidence of discordance is reported to be less and 2 recent analyses report indolent BMI with nodal DLBCL in 5% and 7% of cases. This may reflect a reduction in the widespread use of bilateral BM biopsies over time, and a resulting decreased detection of discordant disease.2,21 Additionally, the definition of discordance has become more refined with the availability of more sensitive methods for identifying lymphomatous involvement. Specifically, there are now improved immunohistochemical techniques as well as wider availability of flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to test for clonality of B cells, and this has resulted particularly in the easier identification of benign lymphoid aggregates.

Discordant indolent BMI in patients with DLBCL

| Reference . | # of patients with any lymphomatous BMI (%) . | # of patients with discordant BMI (%) . | Treatment . | Prognostic significance of discordant vs concordant disease . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 22 (28%) | 11 (14%) | CHOP, CVP, M-BACOD, and MACOP-B | 2 y OS of 36% in discordant disease vs 11% in concordant disease |

| 4 | 43 (29%)* | 21 (14%)* | Chlorambucil/vincristine/prednisone, or CAP-BOP | Superior OS with discordant disease compared with concordant disease (P = .05) |

| 22 | 50 (N/A) | 19 (N/A) | Anthracycline-based regimens | 5 y OS of 79% with discordant disease vs 12% with concordant disease (P = .002) |

| 19 | 20 (34%) | 14 (24%) | proMACE/MOPP, proMACE/cytaBOM, CHOP, CVP, M-BACOD, and COMLA | Mean OS of 47.7 mo in discordant disease vs 13.1 mo in concordant disease (P < .05) |

| 23 | N/A | 21 (N/A) | Unknown chemotherapy regimens ± radiation therapy | Not assessed |

| 32 | 72 (16%) | 18 (4%) | Not described | Not assessed |

| 20 | 47 (27%) | 34 (20%) | CHOP or CHOP-like regimens | Superior PFS and OS with discordant disease compared with concordant disease (P = .055 and .05, respectively) |

| 1 | 55 (11%) | 26 (5%) | CHOP or CHOP-like regimens | 5 y OS of 62% with discordant disease vs 10% with concordant disease (multivariate P = .002) |

| 2 | 125 (16%) | 58 (7%) | R-CHOP | 3 y PFS of 56% in discordant disease vs 37% in concordant disease (multivariate P < .001); 3 y OS of 69% in discordant disease vs 49% in concordant disease (multivariate P = .007)† |

| 21 | 80 (13%) | 32 (5%) | R-CHOP | 3 y PFS of 57% in discordant disease vs 30% in concordant disease (multivariate P < .001); 3 y OS of 64% in discordant disease vs 39% in concordant disease (multivariate P = .011)† |

| Reference . | # of patients with any lymphomatous BMI (%) . | # of patients with discordant BMI (%) . | Treatment . | Prognostic significance of discordant vs concordant disease . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 22 (28%) | 11 (14%) | CHOP, CVP, M-BACOD, and MACOP-B | 2 y OS of 36% in discordant disease vs 11% in concordant disease |

| 4 | 43 (29%)* | 21 (14%)* | Chlorambucil/vincristine/prednisone, or CAP-BOP | Superior OS with discordant disease compared with concordant disease (P = .05) |

| 22 | 50 (N/A) | 19 (N/A) | Anthracycline-based regimens | 5 y OS of 79% with discordant disease vs 12% with concordant disease (P = .002) |

| 19 | 20 (34%) | 14 (24%) | proMACE/MOPP, proMACE/cytaBOM, CHOP, CVP, M-BACOD, and COMLA | Mean OS of 47.7 mo in discordant disease vs 13.1 mo in concordant disease (P < .05) |

| 23 | N/A | 21 (N/A) | Unknown chemotherapy regimens ± radiation therapy | Not assessed |

| 32 | 72 (16%) | 18 (4%) | Not described | Not assessed |

| 20 | 47 (27%) | 34 (20%) | CHOP or CHOP-like regimens | Superior PFS and OS with discordant disease compared with concordant disease (P = .055 and .05, respectively) |

| 1 | 55 (11%) | 26 (5%) | CHOP or CHOP-like regimens | 5 y OS of 62% with discordant disease vs 10% with concordant disease (multivariate P = .002) |

| 2 | 125 (16%) | 58 (7%) | R-CHOP | 3 y PFS of 56% in discordant disease vs 37% in concordant disease (multivariate P < .001); 3 y OS of 69% in discordant disease vs 49% in concordant disease (multivariate P = .007)† |

| 21 | 80 (13%) | 32 (5%) | R-CHOP | 3 y PFS of 57% in discordant disease vs 30% in concordant disease (multivariate P < .001); 3 y OS of 64% in discordant disease vs 39% in concordant disease (multivariate P = .011)† |

CAP-BOP, cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-procarbazine-bleomycin-vincristine-prednisone; COMLA, cyclophosphamide-vincristine-methotrexate-cytosine-arabinoside-leucovorin; CVP, cyclophosphamide-vincristine-prednisone; M-BACOD, methotrexate-bleomycin-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide-vincristine-dexamethasone; MACOP-B, methotrexate-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide-vincristine-prednisone-bleomycin; N/A, not applicable or data not reported; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; proMACE/CytaBOM, cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-etoposide-cytarabine-bleomycin-vincristine-methotrexate-leucovorin-trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; proMACE/MOPP, prednisone-methotrexate-leucovorin-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide-etoposide.

For LN histology both DLBCL and immunoblastic lymphoma were included.

Result controlled for IPI.

Despite the availability of these technologies in recent times, few studies have focused on the clonal relationship of discordant lymphomas.23 Chigrinova et al performed genomic profiles using high-density genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism–based arrays on 27 biopsies and predicted prognosis based on BMI, the presence of specific cytogenetic aberrations, and the diagnosis of concordant vs discordant histology. Samples with concordant BMI had a distinct genetic profile, with low frequency gains of chromosome 7 or loss of 6q. There were too few cases of discordant BMI to determine if the group had a significantly different molecular profile compared with patients without BMI.24 Kremer et al analyzed 21 cases of DLBCL with discordant BMI by PCR for immunoglobulin (Ig) gene rearrangements and bcl-2 rearrangements with subsequent sequencing in selected cases.23 To enrich for the tumor cells, laser capture microdissection of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were used. Three of the original 19 histologically discordant cases were excluded as they were found to be reactive lymphoid aggregates on further review. A clonal relationship was identified in two-thirds of discordant cases, with the remaining one-third exhibiting a different clone. These data suggest that discordant BMI is overestimated, as a subset of cases will be benign lymphoid aggregates and additionally, a subset of discordant indolent disease found on BM biopsy will be clonally related, suggesting transformation of the original indolent neoplasm (Figure 1). Furthermore, it is unclear if the remaining patients with non-clonally related lymphomas have particular risk factors for developing two unrelated lymphomas, such as an underlying immunodeficiency. These interesting questions should prompt further investigation to better elucidate the clonal evolution and biology of discordance.

Discordant histology vs discordant clonality. For patients with DLBCL at a nodal site, lymphomatous BMI may be either histologically concordant large B-cell involvement or histologically discordant small B-cell involvement, which suggests an indolent BCL involving the BM. Histologically discordant BMI may be either clonally related or clonally unrelated to the nodal DLBCL with molecular analysis.

Discordant histology vs discordant clonality. For patients with DLBCL at a nodal site, lymphomatous BMI may be either histologically concordant large B-cell involvement or histologically discordant small B-cell involvement, which suggests an indolent BCL involving the BM. Histologically discordant BMI may be either clonally related or clonally unrelated to the nodal DLBCL with molecular analysis.

Impact of discordance on outcome

The prognostic significance of discordant disease in the pre-rituximab era is limited by small sample sizes and the retrospective nature of the analyses. However, some studies have shown that patients with DLBCL and concordant BMI have an inferior OS compared with those with discordant BMI (who interestingly have survival rates similar to cases without lymphomatous BMI).4,19,25 In addition, a decrease in OS has been observed when a greater proportion of large cells were present in the marrow infiltrate.20,26 Interestingly, patients with concordant histology had an inferior OS independent of the International Prognostic Index (IPI), whereas those with discordant BMI had no significant effect on survival even when accounting for IPI.1

The data regarding the rate of relapse following initial therapy in the presence of discordant BMI are conflicting. In a small series of 13 patients with discordant BM histology, all documented recurrences were of the original large cell lymphoma, rather than relapsed indolent marrow disease. Six of 7 of these relapses occurred within the first 2 years after diagnosis.25 Conversely, others have reported that patients with discordant marrow histology have a higher rate of late relapse, with histology showing indolent disease in 7 of 10 relapsed patients. Over half the cases with disease progression occurred more than 2 years after diagnosis.22 At this point in the pre-rituximab era of therapy, it was unclear whether a diagnosis of discordance truly implied a higher rate of relapse, and if the relapse involved the aggressive or the indolent clone.

In the post-rituximab era, disparate outcomes of discordant and concordant involvement are similar to in the pre-rituximab era. In a recent retrospective analysis of patients with DLBCL receiving rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), those with concordant marrow involvement had a worse OS and PFS than patients without BMI even after controlling for IPI.2 In a univariate analysis, patients with discordant BMI had a significantly worse PFS, but not OS, compared with patients with no BMI. Discordant BMI was not an independent prognostic indicator of either OS or PFS in this multivariate analysis when controlled for IPI. Although these results are intriguing, it has been argued that this particular study is limited by the lack of correlation with full gene expression profiling.27 Similarly, in the previously discussed analysis of 133 patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP, concordant but not discordant BMI also correlated with worse OS and PFS in a univariate analysis, not controlling for IPI.24 A more recent study also showed that concordant BMI was predictive of worse OS and PFS independent of IPI score, whereas once again discordant BMI was not.21

In terms of patterns of relapsed disease in the post-rituximab era, there is a clearer pattern of relapse, which is predominantly of the aggressive large BCL rather than indolent disease. In 2011, Sehn et al reported that the majority of patients with DLBCL having discordant marrow involvement with relapsed disease had progression of the aggressive lymphoma rather than the indolent lymphoma initially found in the marrow (92%; or 22 out of 24 patients), and in 88% of cases disease progression occurred in the first 2 years after diagnosis.2 The above studies are summarized in Table 1.

Discordant BMI in indolent BCL

Concordant BMI has long been known to predict worse survival outcomes in patients with nodal follicular lymphoma (FL), as it results in upgrading to an Ann Arbor stage of IV and thus a higher FL IPI score.28 Concordant BMI has been estimated to occur in 40% to 70% of patients with FL.29 In a study of discordant lymphomas reported in 1995, 2 patients with FL thought to have discordant lymphoma on BM biopsy were found to have bcl-2 gene rearrangements, suggesting the presence of FL in the marrow rather than true discordance.30

Recently, in a Norwegian series of 96 patients with FL, concordant BMI determined by Ig heavy and light chain gene rearrangement analysis predicted worse survival, even when present in the absence of histologically concordant BMI.29 No cases of histologic discordance incidentally found on Ig chain rearrangement PCR were reported, suggesting that clonally unrelated disease in the marrow is uncommon in FL. Similarly, in a series of 91 patients with FL in which BMI was determined both by histology as well as flow cytometry, no cases of discordant lymphomatous involvement were reported.31 In a large series of 450 patients with NHL, including 345 cases with LN or other biopsy material available to view, only 6 patients with FL on an extramedullary biopsy specimen had DLBCL BMI by histology, and no other discordant histologies were described.32 In a recent British series of 345 patients with NHL for whom both LN and BM biopsy were available, only 8 patients with FL were found to have discordant marrow disease by histology, all of which were classified as DLBCL.33

Discordant BMI in marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) appears to be similarly infrequent. In a recent series, no cases of discordant histology on BM biopsy of LN-diagnosed MZL or mantle cell lymphoma were found.33 BM pathology was studied retrospectively by Boveri et al in 120 patients with nodal, extranodal, and splenic MZL; prevalence of histologic BMI was 90% for splenic MZL, 54% for nodal type, and 22% for extranodal MZL. In all these subtypes, when BMI was found, the marrow showed similar cytologic and immunophenotypic profiles to the original disease site, suggesting that discordant BM histology is infrequent in this subtype of NHL.34 As expected, concordant BMI was significantly associated with more advanced Ann Arbor stage, presence of B symptoms, presence of leukemic disease, higher number of nodal and extranodal sites, and higher IPI and age-adjusted IPI. Twenty-seven patients underwent repeat BM biopsy after diagnosis and 3 patients were then found to have discordant BM findings. Two patients with previously negative BM biopsies showed a shift to higher grade large BCL 12 and 6 years after diagnosis, and 1 patient had a “myeloma” like infiltrate after receiving CHOP.34

Another possible rare presentation is the presence of 2 types of indolent lymphomas diagnosed simultaneously from different sites. Indeed, some case reports have described the diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma with MZL,35 or the association of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with FL.13,14

In summary, discordant BMI in indolent lymphomas has mostly been described for FL, and even here the frequency appears to be low, and mostly manifested as DLBCL on BM biopsy, probably indicative of transformed disease.

Role of PET imaging as non-invasive evaluation

A number of studies have suggested that fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) can predict BMI with high sensitivity in aggressive NHLs.36-40 In contrast, the literature describing BMI in FL is more limited and suggests that PET is less sensitive to detect concordant BMI by FL.41,42 In one study, only 13 of 24 patients with biopsy-proven BMI by FL had involvement by PET evaluation, with PET findings suspicious for BMI being defined as diffuse FDG uptake in hollow bones, pelvis, and spine or diffuse uptake in hollow bones with focal uptake in spinal lesions.43 In another series, predominantly of patients with DLBCL, focal areas of increased FDG uptake anywhere in the BM were considered representative of disease. PET could not detect the established BMI detected in the 4 cases with grades 1 to 2 FL.41 More recently, El-Najjar et al, using a semi-quantitative analysis of PET images to assess BMI in FL, showed an improved sensitivity (58% vs 31%) and specificity (96% vs 92%) of detection when compared with visual inspection of the same images by the radiologist.42

In a prospective analysis of 110 patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL, 21 patients had a BM biopsy with evidence of lymphoma (7 concordant and 14 discordant). Six of the 7 patients with concordant BMI also had abnormal PET uptake, defined as at least one focus of moderate or intense FDG uptake in a BM territory using a 3-point system (1 = low, 2 = moderate, and 3 = high). Conversely, only 4 of 14 patients with discordant involvement were PET positive. These results suggest that PET can be helpful in predicting concordant BMI. It is less clear if PET has any utility in predicting discordant BMI. Unlike in previous studies, in this study there was no difference in survival between patients with concordant or discordant involvement, possibly in part due to the small sample size.44

A multinational study of 327 patients with DLBCL who underwent PET and BM biopsy at diagnosis, in which PET positivity was defined as focal BM FDG uptake greater than liver uptake, revealed that only 10 of 241 patients with BM negativity by PET had BM biopsy positivity for lymphoma.45 Two cases were discordant and 8 were concordant. Interestingly, 6 of the concordant cases demonstrated <10% tumor cells in the BM, presumably limiting detection on PET imaging. In a multivariate analysis, BMI detected by both PET and biopsy was associated with a significant decrease in OS. This effect was not seen with BMI detected either by BM biopsy or PET alone, suggesting that BMI identified by PET has independent prognostic value. Therefore, the authors hypothesize that PET scans, which preferentially detect concordant large cell BMI, are more specific indicators of poor prognosis disease in the marrow.

Finally, a meta-analysis of 7 studies, including 654 patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL, showed that FDG-PET computed tomography (CT) had a pooled estimate of 88.7% sensitivity and 99.8% specificity.46 This study further supports the view that a BM biopsy positive for lymphoma, whether concordant or discordant, does not change the management of a patient if the PET scan is interpreted as negative for BMI. It is important to note that the interpretation of the above studies is limited by the heterogeneity in criteria used for PET positivity of the BM, with some using comparison with normal liver uptake and others using other subjective assessments.

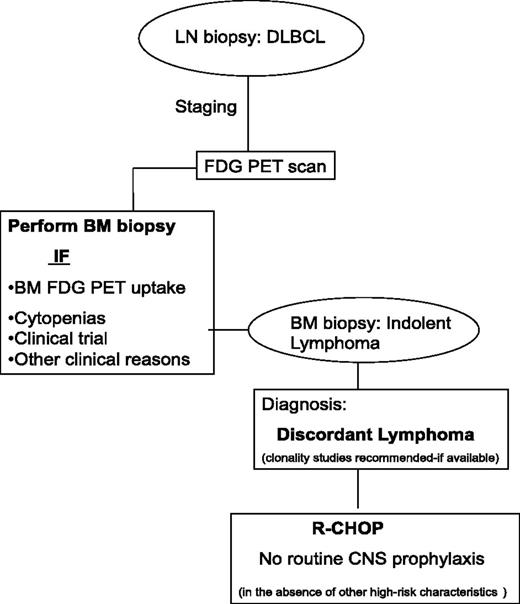

Based on all the above and additional reports that support the role of PET-CT in the diagnosis of BMI, updated guidelines have recently been published by Cheson et al.47-50 According to these recommendations, a BM biopsy is no longer indicated for the routine staging of most DLBCL, if the PET-CT is negative for BMI. However, in DLBCL cases with discordant BMI, FDG-PET avidity of indolent lymphoma in the marrow may be very low and not detect discordant disease. Therefore, in select cases where discordance is suspected, cytopenias are found, or as part of clinical trials BM biopsies should be performed even in the presence of negative FDG-PET findings (Figure 2).

Approach to the diagnosis of discordant lymphoma. In the staging of DLBCL, a BM biopsy should be performed if there is increased PET-FDG uptake or for other clinical reasons such as the presence of cytopenias. If discordant indolent lymphoma is diagnosed in the BM, clonality studies should be considered if available. In contrast to concordant BMI in DLBCL, studies suggest that discordant involvement (with indolent disease in the BM) is not associated with an increased risk of CNS disease.

Approach to the diagnosis of discordant lymphoma. In the staging of DLBCL, a BM biopsy should be performed if there is increased PET-FDG uptake or for other clinical reasons such as the presence of cytopenias. If discordant indolent lymphoma is diagnosed in the BM, clonality studies should be considered if available. In contrast to concordant BMI in DLBCL, studies suggest that discordant involvement (with indolent disease in the BM) is not associated with an increased risk of CNS disease.

Therapeutic approach to discordant lymphomas

There are no randomized trials or prospective studies addressing specific treatments for either nodal DLBCL with discordant indolent BMI or indolent nodal lymphomas with discordant aggressive lymphoma BMI. The majority of patients with DLBCL and discordant BMI with indolent lymphoma on biopsy are treated with anthracycline-based regimens, such as R-CHOP. As referenced above, most retrospective analyses demonstrate that the presence of indolent BMI does not affect prognosis for patients treated with aggressive immunochemotherapy. If discordant aggressive lymphoma is found on BM biopsy of a patient with indolent nodal lymphoma, anthracycline-based treatment directed at the aggressive histology is typically used but again this has been poorly studied. Although a majority of histologically discordant lymphomas in the BM are clonally related to the LN histology, a reasonable therapeutic approach is to target the aggressive histology, as described in retrospective series (Figure 2).1,2,4,5,19-22,25 The role of upfront autologous stem cell transplant following first remission in transformed lymphomas has not been well established and there is no data assessing its role in discordant cases.51,52

An increased risk of central nervous system (CNS) involvement and CNS relapse in newly diagnosed patients with DLBCL who have concordant BMI has been well described,53-55 and therefore cerebrospinal fluid sampling for lymphomatous involvement and prophylactic CNS-directed therapy are common practice.56,57 In contrast, discordant indolent BMI in patients with nodal DLBCL has not been associated with an increased risk of CNS involvement/relapse and should not mandate cerebrospinal fluid sampling in the absence of other high-risk characteristics.2,19,22,25

Conclusion/summary

In summary, concordant BMI with DLBCL portends a worse outcome and inferior OS compared with cases without BMI. In contrast, and importantly, recognizing that this is a poorly studied area with a lack of large or prospective data, discordant BMI with an indolent BCL in newly diagnosed DLBCL does not appear to impact negatively on prognosis. Although FDG-PET is a helpful tool in the diagnosis of concordant BMI in DLBCL, it is probably much less sensitive in detecting discordant BMI. Extrapolating from the limited number of studies that have looked at Ig gene rearrangements in these cases, a high proportion of histologically discordant lymphomas appear to be clonally related.23 The molecular biology of discordance has been poorly studied and should be a focus of future studies in this area that aim at defining optimal approaches for these diseases.

Acknowledgments

There were no funding sources for the preparation of this manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors were involved in preparing the manuscript, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.B. and K.D. received funding from the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kieron Dunleavy, Lymphoid Malignancies Branch, National Cancer Institute, Building 10, Room 4N-115, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: dunleavk@mail.nih.gov.

References

Author notes

J.B. and T.T. contributed equally to this study.

A.P. and K.D. contributed equally to the study.