Background

Cancer drugs now account for a greater fraction of the national health care expenditure than ever before. A new movement has been formed that argues for meaningful definition of the value of drugs as a pre-requisite for their approval as well as for clinical decision-making. Numerous frameworks have been designed to allow comparison of different pharmacological agents based on patient-related factors (efficacy, safety, cost). However, these formulas largely ignore chronic, long-term toxicities which are particularly important in the case of highly-curable cancers like Hodgkin Lymphoma and testicular cancer. We propose a drug value scheme that incorporates debilitating and life-threatening long-term toxicities along with traditional factors (efficacy and acute safety) when defining a drug's merit.

Methods

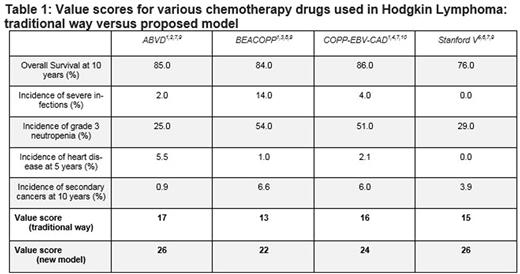

A longitudinal framework for assessing drug value is suggested. Pertinent drug-related characteristics - efficacy, acute adverse events, and long-term toxicities - are included. For each drug characteristic, patient-centred surrogate markers are chosen: efficacy is defined by the 10-year overall survival, acute safety by the rate of neutropenia and life-threatening infections, and long-term toxicity by the cumulative incidence of secondary cancers and heart disease at 5 and 10 years, respectively. Advanced Hodgkin Lymphoma is chosen for simulation. The most commonly used regimens are compared. Data from high-value prospective clinical trials (see references) are used to grade each regimen. Points are given for each percentile range in each category (higher score for greater efficacy and lower toxicity; see Appendix 1). Percentile intervals are chosen according to the presumed clinical impact. The net value of each regimen is assessed by adding the score for each individual care component and comparing it to a similar model that does not include long-term toxicity.

Results

Risk score calculation yielded results as shown in Table 1. ABVD And Stanford V gained the highest score (26; of 30) while COPP-EBV-CAD and BEACOPP obtained lower scores (24 and 22, respectively). Stanford V reached a better value score than COPP-EBV-CAD, and was equivalent to ABVD, in contrast to a drug value scheme that neglected long-term toxicities, in which it was inferior to both. The superiority of ABVD to COPP-EBV-CAD and BEACOPP persisted in the model, as was the overall advantage of COPP-EBV-CAD over BEACOPP.

Conclusions

As the treatment of cancer continues to improve, value should no longer be derived only from a drug's overall survival and acute injury profiles. A more comprehensive appreciation of a drug's benefit-to-risk ratio entails an understanding of its more distant health implications. Our model shows that such an easily-constructible framework results in a different value estimation of drugs compared with the traditional one.

Appendix 1:

Value Score:

- Efficacy

* Overall Survival: 7 if <74.9%, 8 if 75.0-80.9%, 9 if 81.0-85.9%, 10 if 86.0-88.9%, 11 if >89.0%

- Acute toxicity

* Incidence of severe infections: 3 if >10.0%, 4 if 5.0-9.9%, 5 if <4.9%

* Incidence of grade 3 neutropenia: 1 if > 50.0%, 2 if 28.0-49.9%, 3 if <27.9%

- Late toxicity

* Incidence of heart disease at 5 years: 1 if >5.6%, 3 if 4.0-5.5%, 4 if 2.0-3.9%, 5 if <1.9%

* Incidence of secondary cancers at 10 years: 6 if <3.9%, 4 if 4.0-9.0%, 3 if 9.1-13.0%, 1 if >13.1%

*** Example: ABVD value score = 9 (for OS of 85%) + 5 (for severe infection incidence of 2%) + 3 (for grade 3 neutropenia incidence of 25%) + 3 (for 5-year heart disease incidence of 5.5%) + 6 (for 10-year secondary cancer incidence of 0.9%) = 26

References:

1. Merli F, et al. JCO. 2016;34(11):1175-81

2. Manuel Gotti, et al. Lymphoma. 2013, Article ID 952698, 7 pages

3. Kara M, et al. Blood. 2011;117:2596-2603

4. Evens, et al. Br J Haematol. 2013;161(1): 76-86

5. Chisesi T, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2011;29:4227-4233

6. Gobbi PG, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:9198-9207

7. Bhanu Vakkalanka. Advances in Hematology, vol. 2011, Article ID 656013, 7 pages, 2011

8.Massimo Federico et al. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(5):805-811

9.Gobbi P G, et al. JCO. 2005; 23 (36):9198-9207

10. S. M. Edwards-Bennett, et al. Annals of Oncology. 2010; 21: 574-581

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal