Abstract

Background. In AML, the frequency of TET2 mutations increases with age ranging from 1-5% in children to 6-27% in adults. These mutations have both been reported to exert unfavorable or neutral effects on patient outcomes. Besides mutations, fluctuation in TET2 expression has been evidenced in AML while we recently found that TET2 exon 2 skipping (TET2E2S) is associated with favorable outcome in adult AML (Mint-Mohamed et al., ASH 2014 and submitted). Here we investigated the effect TET2 expression and TET2E2S in homogeneously treated adult and pediatric AML patients with intensive chemotherapy (IC).

Methods. Samples derived from 341 patients with available high-quality RNA and enrolled in the ELAM2 protocol (n=120) and the ALFA-0701 protocol (n=221).qRTPCR amplification of 2 conserved TET2 mRNA sequences was performed with GUS and ABL as reference genes. TET2 exon 2 skipping was quantified throughexon(E)-specific qRTPCR (qESPCR) amplification of E1E3 (spliced) and E2E3 (unspliced) TET2 isoforms. TET2E2S was quantified by calculating the ratio E1E3/E2E3. Patients were classified according to their standardized cytogenetic and molecular (NPM1 mutations, FLT3-ITD, CEBPA double mutations) risk subgroups. In children, treatment consisted in 1 induction course (AraC and mitoxantrone) and 3 consolidation courses (course 1 and 3 with high dose AraC); children with either intermediate or high-risk disease were candidates for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in complete remission (CR) after 1 to 2 consolidation courses. Adult patients were given a 3+7 induction course without (control group, n=110) or with fractionated intravenousgemetuzumab ozogamicin (GO) (n=111) as already described (Castaigne S, Lancet 2012; 379:1508-1516).

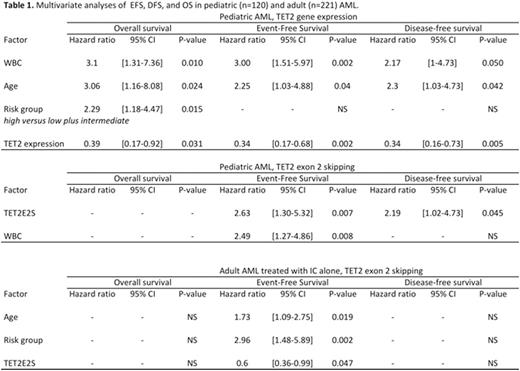

Results. In pediatric AML, median age, median WBC, CR rate, relapse rate, median follow-up, 3-years EFS, DFS, and OS were 9.4 years, 19 G/L, 95%, 29%, 48 months, 60±5%, 63±6%, and 72±5%, respectively. Lower TET2 expression was associated with inferior EFS (3-years: 44±10%vs 69±6%, log-rank p = 0.01), DFS (51±8%vs 64±5% p=0.02), and OS (60±8%vs 83±3%, p=0,0003) while TET2E2S was associated with inferior EFS (44±8%vs 70±7%, p = 0.006) and OS (61±7%vs 81±4%, p=0.01). For TET2 expression, multivariate analysis identified WBC, age, risk group, and TET2 expression as independent prognostic factors for EFS and OS, and age, WBC, and TET2 expression for DFS (Table 1). For TET2 splicing, WBC and TET2E2S independently predicted EFS while TET2E2S alone independently predicted DFS (Table 1). In the low- (n=29) and intermediate-risk (n=62) groups, lower TET2 expression remained associated with shorter 3-years EFS. There was no significant correlation between TET2 expression and TET2E2S and TET2E2S retained its negative prognostic impact in the 85 patients with higher TET2 expression (3-years EFS 48±8vs 84±6%, p=0.004). In adult AML, median age, median WBC, CR rate, relapse rate, median follow-up, 3-years EFS, DFS, and OS were 62 years, 8 G/L, 76%, 59%, 47 months, 26±3%, 30±4%, and 44±4%, respectively. In the entire population, TET2 expression and splicing had no significant effect on outcome. In the 110 patients treated with IC alone, TET2 expression was associated with inferior OS (25±9vs 29±9%, p=0.02) while TET2E2S was associated with better EFS (17±5vs 7±6%, p=0.008), DFS (28±8vs 8±6%, p=0.02), and OS (46±8vs 29±8%, p=0.05). TET2E2S, age, and disease risk represented independent prognostic factors for EFS (Table 1). In the GO arm, TET2 expression had no significant effect on outcome whereas TET2E2S was associated with inferior EFS (27±5vs 60±12%, p=0.01), DFS (31±6vs 63±12%, p=0.05), and OS (39vs 72±11%, p=0.04).

Conclusion. Inchildren, higher TET2 expression confers a favorable outcome whereas TET2E2S represents an independent unfavorable prognostic factor. In adult treated with IC alone, present results confirm the favorable prognostic impact of TET2E2S and the weak prognostic effect of TET2 expression. In contrast, in patients fulfilling the same inclusion criteria, TET2E2S loses its favorable prognostic effect and is even associated with unfavorable outcome when GO is associated to IC. While TET2 expression and splicing might represent useful biomarkers, the data highlight the strong difference in tumor biology between adult and pediatric AML and suggest distinct relationships between TET2E2S and the cytotoxic effect of GO plus IC versus IC alone.

Thomas:Pfizer: Consultancy.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal