Key Points

miR-28 is a regulator of the GC reaction that dampens B-cell receptor signaling and impairs B-cell proliferation and survival.

miR-28 has antitumoral activity in BL and DLBCL.

Abstract

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma comprises a variety of neoplasms, many of which arise from germinal center (GC)-experienced B cells. microRNA-28 (miR-28) is a GC-specific miRNA whose expression is lost in numerous mature B-cell neoplasms. Here we show that miR-28 regulates the GC reaction in primary B cells by impairing class switch recombination and memory B and plasma cell differentiation. Deep quantitative proteomics combined with transcriptome analysis identified miR-28 targets involved in cell-cycle and B-cell receptor signaling. Accordingly, we found that miR-28 expression diminished proliferation in primary and lymphoma cells in vitro. Importantly, miR-28 reexpression in human Burkitt (BL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) xenografts blocked tumor growth, both when delivered in viral vectors or as synthetic, clinically amenable, molecules. Further, the antitumoral effect of miR-28 is conserved in a primary murine in vivo model of BL. Thus, miR-28 replacement is uncovered as a novel therapeutic strategy for DLBCL and BL treatment.

Introduction

Mature B-cell lymphomas account for the vast majority of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), whose incidence has steadily increased over the past decades. Almost 400 000 new NHL cases are diagnosed and more than 200 000 people are estimated to die every year from NHL worldwide (data from Cancer Research UK). More than 60% of cases of mature B-cell lymphomas are aggressive, fast-growing subtypes and include diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL; 30% of all NHL) and Burkitt lymphoma (BL)/leukemia (2.5% of all NHL).1 Although many aggressive B-cell lymphomas can be cured with current therapies—most commonly, doxorubicin-based combination chemotherapy with rituximab—these are highly intensive treatments, often requiring hospitalization. Moreover, almost half of DLBCL and BL cases are resistant to these approaches or relapse within 5 years of treatment.2 It is therefore crucial to identify new therapeutic strategies that are more effective and less toxic than current antilymphoma therapies.

Mature B-cell lymphomas originate from mature B cells that have germinal center (GC) experience. GCs are transient microstructures that develop in secondary lymphoid organs in response to T cell–dependent antigens and serve to generate high-affinity plasma cells and long-lived memory B cells.3 Within GCs, B cells somatically remodel their antibody genes through somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class switch recombination (CSR), which enable the generation of higher affinity antibodies harboring specialized effector functions. Both SHM and CSR are initiated by activation induced deaminase (AID) through deamination of cytosines on the Ig loci.4,5 AID genotoxic activity provides 1 direct link between the GC reaction, the generation of lymphomagenic chromosome translocations and the propensity of mature B cells for oncogenic transformation.6-8

Antibody affinity is improved in GCs through iterative rounds of selection of variants generated by SHM, a process called affinity maturation.3 Thus, B cells in which SHM gives rise to a B-cell receptor (BCR) with increased affinity for antigen outcompete lower affinity B cells and are selected to proliferate further. In contrast, B cells in which SHM impairs BCR expression or significantly reduces antigen affinity are not rescued for further differentiation; therefore, Ig gene remodeling in GC B cells is intimately coupled to intense proliferation and programmed cell death, events critically dictated by BCR signaling. Human malignant B cells typically maintain surface BCR expression, suggesting that they may use the ability of the BCR to engage downstream proliferation and survival pathways. Likewise, gain-of-function mutations affecting BCR signaling pathways are very common in B-cell lymphoma.1,9

B-cell lymphomagenesis is also influenced by regulators of the GC gene expression program. Mice lacking the transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 are unable to form GCs or produce high-affinity antibodies10 ; conversely, mice constitutively expressing Bcl-6 in B cells develop a B-cell malignancy that recapitulates DLBCL.11 Lymphomagenesis is also promoted by transgenic overexpression of miR-155 and miR-217.12,13

In recent years, microRNA (miRNA)-based therapeutics for cancer treatment has stirred a lot of interest. miRNAs negatively regulate the expression of gene networks through imperfect base-pair binding to the 3′UTR of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs). Many human miRNAs are located in cancer-associated genomic regions,14 and dysregulated miRNAs contribute, as oncogenes (oncomiRs) or tumor suppressors, to the tumorigenic process of numerous cancers, including lymphomas (reviewed in Adams et al,15 Schmidt and Küppers,16 and de Yébenes et al17 ). These unique features of miRNAs may provide novel targets for antitumor therapy (reviewed in Taylor and Schiemann18 and Nana-Sinkam and Croce19 ).

Here we have characterized miR-28, a GC-specific miRNA frequently lost during B-cell transformation. Our results show that miR-28 regulates the GC reaction, hindering B-cell proliferation and survival. We show that reexpression of miR-28 impairs tumor growth in several lymphoma models, demonstrating the feasibility of miR-28 replacement for the treatment of B-cell NHL.

Methods

Expression constructs and transductions

miR-28 detection by qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen) and miR-28-5p was measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using miR-28 miRCURY LNA primers (Exiqon). U6 amplification was used as a normalization control. Reactions were performed in a 7900HT fast real-time PCR thermocycler (Applied Biosystems).

RNA and multiplexed isobaric labeling analysis

Ramos cells transduced with miR-28 or scrambled pTRIPZ vectors were selected with puromycin (0.4 μg/mL) and induced for 2 days with doxycycline (Dox) (0.5 μg/mL); red fluorescent protein+ (RFP+) cells were isolated with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) Aria cell sorter and subjected to quantitative transcriptome and proteomic analysis (supplemental Materials and methods).

Lymphoma models

For subcutaneous xenografts, 2-10 × 106 Ramos cells were resuspended in 100 μL phosphate-buffered saline, mixed with 100 μL Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and injected into nonobese diabetic severe combined immunodeficiency γ (NSG) mice (8-14 weeks old). When transduced cells were used, Dox (Sigma-Aldrich) was administered at 0.04% in the drinking water. To establish subcutaneous λ/MYC transgenic (λ-MYC) primary tumors, enlarged lymph nodes were extracted from 4-to-8-month-old sick λ-MYC animals, and 107 cells were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of NSG mice. Subcutaneous tumor volume was measured 3 times per week with a digital caliper using the following formula: volume = (width)2 × length/2. For the systemic model of BL, 2 × 106 primary lymphoma cells from λ-MYC mice were IV injected into the tail vein of receptor NSG mice.

B-cell lymphoma treatment with miR-28 mimic

miRNA mimics for miR-28 or control were purchased from Ambion. For intratumor administration, established tumors were injected with 0.1 or 0.5 nmol miRNA mimics together with Invivofectamine (Ambion) 3 times, separated by 3 to 4 days. For intravenous administration, mice with established tumors were injected twice with 7 nmol miRNA mimics, with injections separated by 4 days.

Results

miR-28 regulates the GC reaction

miR-28 is expressed in mouse and human GC B cells21,22 ; however, its role in the GC reaction remains unknown. We measured miR-28 expression by qRT-PCR in naïve B cells (CD19+GL7−), GC B cells (CD19+GL7+), and post-GC B cells (CD19+GL7−IgA+) isolated from Peyer’s patches (gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 1A); we found that miR-28 expression sharply increased in GC B cells and declined soon afterward in post-GC cells (Figure 1A, top). Likewise, miR-28 expression progressively increases during the GC reaction, as measured in splenic GC B cells of mice immunized with sheep red blood cells (Figure 1A, bottom; gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 1B). However, we did not detect significant differences in miR-28 expression between light zone and dark zone GC B cells (supplemental Figure 1C-D).

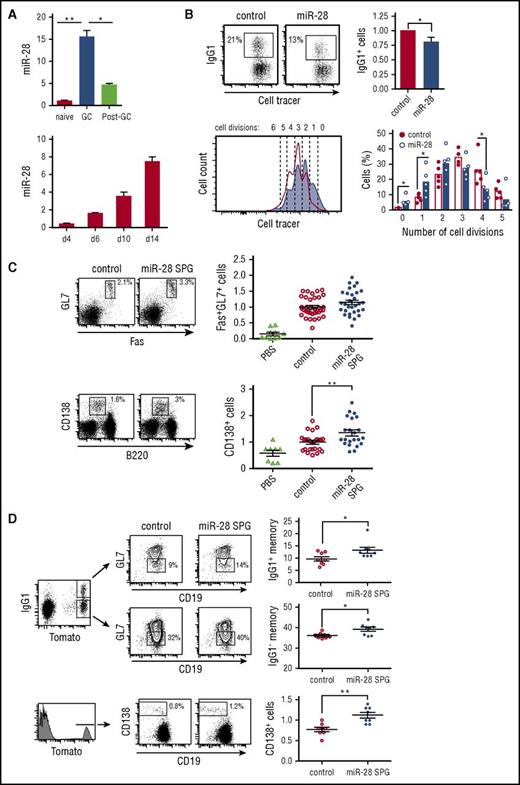

miR-28 regulates the GC reaction. (A) miR-28 expression was assessed by qRT-PCR in naïve B cells (CD19+GL7−IgA−), GC B cells (CD19+GL7+), and switched B cells (post-GC, CD19+GL7−IgA+) from Peyer’s patches (top) (n = 2) and in spleen GC B cells (CD19+Fas+GL7+) on the indicated days after immunization of C57/BL mice with sheep red blood cells (bottom) (n = 2) (gating strategy is shown in supplemental Figure 1A-B). (B) Spleen B cells were labeled with violet cell tracer, stimulated with lipopolysaccharide and IL-4, and transduced with control or pre-miR-28–containing retroviral constructs. CSR to IgG1 was assessed by FACS analysis of GFP+ cells 3 days after transduction. Left, representative FACS plot; right, quantification (n = 5). Lower panels: number of cell divisions was quantified with cell tracer by FACS analysis 3 days after transduction. Left, representative histogram (open line, control-transduced cells; shaded histogram, miR-28–transduced cells). Number of cell divisions is indicated. Right, quantification (n = 5). (C-D) Mouse chimeras transplanted with bone marrow cells transduced with miR-28 SPG or empty vector were analyzed by FACS 10 to 14 days after immunization. (C) Left, representative plots of GC (top) and plasma (bottom) cells; right, quantifications after normalization to the mean of control mice in each individual experiment. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS): nonimmunized chimeric mice. Analyses were performed gating on CD45.1+ GFP+ cells. Data are from 6 (GC) and 4 (plasma cell) independent transplantation and immunization experiments. (D) miR-28 SPG or empty vector chimeras were generated using bone marrow cells from R26-Tomatoki/+; AIDCreki/+ mice to track GC-experienced cells. Left, representative plots of Tomato+IgG1+ and Tomato+IgG1− memory and Tomato+ CD138+ plasma B cells are shown; right, quantifications. Analyses were performed gating on Tmt+ GFP+ cells. Data are from 2 independent transplantation and immunization experiments. Each symbol (C-D) represents an individual mouse. *P < .05, **P < .01, unpaired Student t test (A-D).

miR-28 regulates the GC reaction. (A) miR-28 expression was assessed by qRT-PCR in naïve B cells (CD19+GL7−IgA−), GC B cells (CD19+GL7+), and switched B cells (post-GC, CD19+GL7−IgA+) from Peyer’s patches (top) (n = 2) and in spleen GC B cells (CD19+Fas+GL7+) on the indicated days after immunization of C57/BL mice with sheep red blood cells (bottom) (n = 2) (gating strategy is shown in supplemental Figure 1A-B). (B) Spleen B cells were labeled with violet cell tracer, stimulated with lipopolysaccharide and IL-4, and transduced with control or pre-miR-28–containing retroviral constructs. CSR to IgG1 was assessed by FACS analysis of GFP+ cells 3 days after transduction. Left, representative FACS plot; right, quantification (n = 5). Lower panels: number of cell divisions was quantified with cell tracer by FACS analysis 3 days after transduction. Left, representative histogram (open line, control-transduced cells; shaded histogram, miR-28–transduced cells). Number of cell divisions is indicated. Right, quantification (n = 5). (C-D) Mouse chimeras transplanted with bone marrow cells transduced with miR-28 SPG or empty vector were analyzed by FACS 10 to 14 days after immunization. (C) Left, representative plots of GC (top) and plasma (bottom) cells; right, quantifications after normalization to the mean of control mice in each individual experiment. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS): nonimmunized chimeric mice. Analyses were performed gating on CD45.1+ GFP+ cells. Data are from 6 (GC) and 4 (plasma cell) independent transplantation and immunization experiments. (D) miR-28 SPG or empty vector chimeras were generated using bone marrow cells from R26-Tomatoki/+; AIDCreki/+ mice to track GC-experienced cells. Left, representative plots of Tomato+IgG1+ and Tomato+IgG1− memory and Tomato+ CD138+ plasma B cells are shown; right, quantifications. Analyses were performed gating on Tmt+ GFP+ cells. Data are from 2 independent transplantation and immunization experiments. Each symbol (C-D) represents an individual mouse. *P < .05, **P < .01, unpaired Student t test (A-D).

To investigate the functional relevance of miR-28 expression in GC B cells, we isolated naïve B cells from mouse spleens, cultured them in the presence of lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-4 (IL-4), and transduced them with miR-28 or control retroviruses (quantification of miR-28 expression shown in supplemental Figure 1E). miR-28 expression decreased the proportion of cells undergoing CSR and the proliferation rate (Figure 1B). We next generated loss-of-function mouse models using a miR-28 sponge construct (miR-28 SPG) (supplemental Figure 1F), which inhibits miR-28 activity by competing for binding to endogenous miR-28 binding sites23 (supplemental Figure 1G). Bone marrow cells were transduced with miR-28 SPG or control retrovirus and transferred to lethally irradiated isogenic recipient mice. Reconstituted mice were immunized with a T cell–dependent antigen and analyzed 10 to 14 days later. Compared with control chimeras, immunized miR-28 SPG chimeras tended to have higher proportions of GC cells (Fas+GL7+; Figure 1C, top) and had significantly increased proportions of plasma cells (CD138+; Figure 1C, bottom). To specifically track GC-derived memory B cells and plasma cells, we performed miR-28 SPG experiments using as donors bone marrow cells from a reporter mouse, in which the expression of Tomato fluorescent protein is irreversibly turned on by AID expression. We found that miR-28 SPG promotes an increase in the proportion of both immunoglobulin G1+ (IgG1+) and IgG1− memory B cells and an increase in GC-derived plasma cells (Figure 1D). Although conditionally deficient mouse models would be required to unambiguously demonstrate that this is an intrinsic B-cell phenotype, our combined gain-and-loss-of function data indicate that miR-28 is a regulator of the GC reaction.

miR-28 is downregulated in GC-derived neoplasms

miRNA profiling in an extensive dataset of human primary GC-derived B-cell neoplasms (GSE 2949324 ) revealed that miR-28 expression is lost in several GC-derived lymphoma subtypes, including BL, DLBCL and follicular lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (Figure 2A). miR-28 downregulation is also a common event in established GC-derived B-cell lines, such as the Ramos and Raji BL cell lines and the MD901 DLBCL cell line (supplemental Figure 2A). These data are consistent with previous reports showing reduced miR-28 expression in various B-cell lymphoma subtypes25,26 and show that loss of miR-28 expression is very frequently associated with GC B-cell transformation, suggesting a possible tumor suppressor role for miR-28 in mature B-cell lymphomas and leukemia.

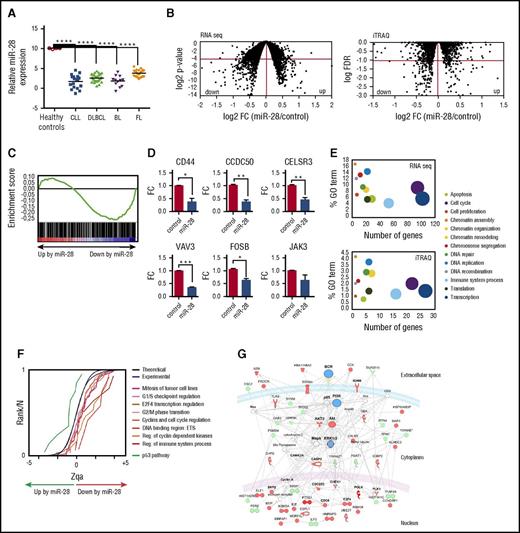

Identification of miR-28 targets in lymphoma B cells. (A) miR-28 microarray expression data (GSE29493) in cohorts of patients with CLL (18 samples), DLBCL (29 samples), BL (12 samples), and follicular lymphoma (FL, 23 samples). Controls were human GC B cells (CD10+ CD19+) extracted from tonsils of healthy donors. Adjusted P values were calculated with the Benjamini and Hochberg method (****FDR <10−4). (B) Ramos BL cells were transduced with scramble or miR-28 vectors, induced with Dox, and flow cytometry isolated RFP+ cells were analyzed by RNA-Seq and iTRAQ for differential transcriptome and proteome characterization, respectively. Plots are volcano representations of transcriptomic and proteomic changes in Ramos cells upon miR-28 reexpression. Dots represent mean fold change (miR-28 Ramos cells/control Ramos cells) at the level of transcripts (RNA-Seq; 6 replicates) or proteins (iTRAQ; 4 replicates) (x-axes) against the statistical significance of the change (y-axes), both in 2-base logarithmic scale. Changes were considered significant at cutoffs of P < .05 (RNA-Seq) or FDR <10% (P < .0038) (iTRAQ) (dots below red lines). (C) Gene set enrichment analysis of predicted miR-28 targets vs transcriptome analysis of miR-28–expressing BL cells (NES = −1.42; P = .004; q = 0.001). (D) qRT-PCR validation of miR-28–mediated transcript downregulation of 6 representative genes found to be significantly downregulated in the RNA-Seq analysis (*P < .05, unpaired Student t test). (E) miR-28–altered transcripts (top) and proteins (bottom) were annotated with functional gene ontology (GO) categories. The x-axes plot the number of miR-28–altered transcripts or proteins within each GO category; y-axes plot the proportion of miR-28–altered transcripts or proteins within each GO category. Circled area represents the relative contribution of each GO category to the total number of miR-28–altered transcripts or proteins. (F) The graph shows the cumulative distributions of the standardized variable at the protein level (Zqa) plotted separately for each miR-28–altered category in the iTRAQ proteomic analysis. (G) Ingenuity pathway analysis of the proteins differentially expressed upon miR-28 expression in BL cells (BCR signaling pathway enrichment, P = 10−46). Upregulated proteins are depicted in green, downregulated in red, and nodes in blue.

Identification of miR-28 targets in lymphoma B cells. (A) miR-28 microarray expression data (GSE29493) in cohorts of patients with CLL (18 samples), DLBCL (29 samples), BL (12 samples), and follicular lymphoma (FL, 23 samples). Controls were human GC B cells (CD10+ CD19+) extracted from tonsils of healthy donors. Adjusted P values were calculated with the Benjamini and Hochberg method (****FDR <10−4). (B) Ramos BL cells were transduced with scramble or miR-28 vectors, induced with Dox, and flow cytometry isolated RFP+ cells were analyzed by RNA-Seq and iTRAQ for differential transcriptome and proteome characterization, respectively. Plots are volcano representations of transcriptomic and proteomic changes in Ramos cells upon miR-28 reexpression. Dots represent mean fold change (miR-28 Ramos cells/control Ramos cells) at the level of transcripts (RNA-Seq; 6 replicates) or proteins (iTRAQ; 4 replicates) (x-axes) against the statistical significance of the change (y-axes), both in 2-base logarithmic scale. Changes were considered significant at cutoffs of P < .05 (RNA-Seq) or FDR <10% (P < .0038) (iTRAQ) (dots below red lines). (C) Gene set enrichment analysis of predicted miR-28 targets vs transcriptome analysis of miR-28–expressing BL cells (NES = −1.42; P = .004; q = 0.001). (D) qRT-PCR validation of miR-28–mediated transcript downregulation of 6 representative genes found to be significantly downregulated in the RNA-Seq analysis (*P < .05, unpaired Student t test). (E) miR-28–altered transcripts (top) and proteins (bottom) were annotated with functional gene ontology (GO) categories. The x-axes plot the number of miR-28–altered transcripts or proteins within each GO category; y-axes plot the proportion of miR-28–altered transcripts or proteins within each GO category. Circled area represents the relative contribution of each GO category to the total number of miR-28–altered transcripts or proteins. (F) The graph shows the cumulative distributions of the standardized variable at the protein level (Zqa) plotted separately for each miR-28–altered category in the iTRAQ proteomic analysis. (G) Ingenuity pathway analysis of the proteins differentially expressed upon miR-28 expression in BL cells (BCR signaling pathway enrichment, P = 10−46). Upregulated proteins are depicted in green, downregulated in red, and nodes in blue.

Transcriptome and proteome profiling of miR-28 targets

To accurately identify the genes regulated by miR-28 in B cells, we performed combined transcriptome and proteome analysis upon inducible reexpression of miR-28 in the Ramos human BL cell line, where miR-28 expression is much lower than in normal GC B cells (supplemental Figure 2A). miR-28 was transduced along with RFP in a Dox-inducible lentiviral vector, which promoted roughly a 40-fold increase of miR-28 levels, but did not affect the expression levels of other miRNAs (supplemental Figure 2B). RFP+ cells were subjected to RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis for transcriptome profiling and to deep quantitative proteomics using multiplexed isobaric labeling (iTRAQ) (complete lists of products identified by RNA-Seq and iTRAQ can be found in supplemental Tables 1 and 2). RNA-Seq analysis revealed that miR-28 induced expression changes in 1202 transcripts (P < .05), 568 of which were downregulated (Figure 2B). We found a significant correlation between this group of downregulated mRNAs and those reported in a previous study for a different cell line25 (supplemental Figure 3; thresholds log2 fold change <−0.4 or >+0.4). In addition, gene set enrichment analysis27 showed that computer-predicted miR-28 targets were significantly enriched in transcripts downregulated by miR-28 (Figure 2C) (P = .004; normalized enrichment score (NES) = −1.42). miR-28–induced downregulation was validated by qRT-PCR for CD44, CCDC50, CELSR3, VAV3, FOSB, and JAK3 (Figure 2D). iTRAQ analysis allowed quantification of more than 7000 proteins, revealing miR-28–induced changes in 277 proteins (10% false discovery rate [FDR], P < .0038,), 171 of which were downregulated (Figure 2B, right). Importantly, we found a consistent sign of expression change induced by miR-28 at the transcriptome and proteome levels (FDR <10% for proteins, P < .05 for mRNAs; supplemental Figure 4).

Pathway enrichment analysis revealed that miR-28–induced transcriptome and proteome changes grouped in remarkably similar cellular function pathways (Figure 2E), and a class-scoring algorithm that identifies alterations in functional categories28 showed that miR-28 expression in Ramos BL cells induces the coordinated downregulation of proteins belonging to cell-cycle progression pathways (Figure 2F). Finally, ingenuity pathway analysis showed that proteins whose levels are altered by miR-28 form a highly significant cluster of genes involved in BCR signaling. This gene network contains 4 main hubs—BCR, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, AKT, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2)—which play pivotal roles in B-cell biology and regulate the induction of cell-cycle and apoptosis regulatory molecules such as CDC6, CDC25C, TNFSF11, and ILF3 (Figure 2G). These results thus suggest that reintroducing miR-28 into lymphoma cells affects the signaling network emanating from the BCR.

miR-28 dampens BCR signaling and impairs B-cell proliferation and survival

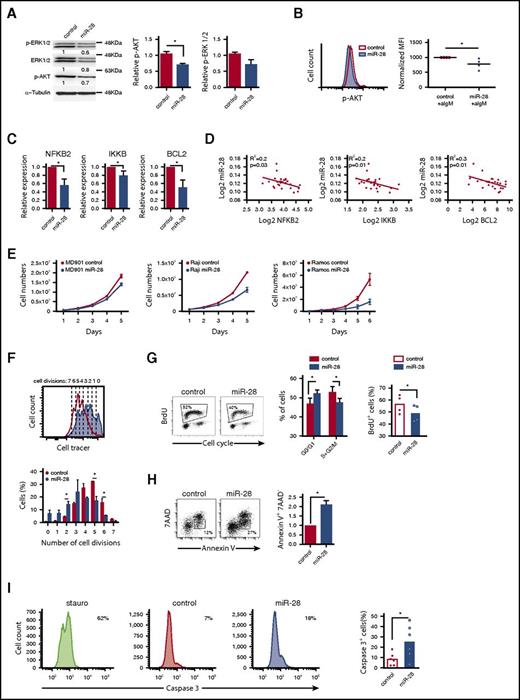

To assess the functional impact of miR-28 on BCR signaling, we quantified the phosphorylated active forms of AKT (p-AKT) and ERK (p-ERK). BL cells transduced with miR-28 tended to have lower p-ERK levels and had significantly lower phosphorylation of AKT-S473 (34% below control cells, P = .02) than control-transduced cells (Figure 3A). Moreover, miR-28–transduced BL cells stimulated with anti-IgM had lower levels of p-AKT than controls (Figure 3B) (P = .04), indicating that miR-28 expression dampens BCR signaling in BL cells.

miR-28 regulates proliferation and cell death in lymphoma B cells by dampening the BCR signaling pathway. (A) Extracts of RFP+ Ramos BL cells, transduced with control or pre-miR-28–containing retroviral constructs, were immunoblotted with antibodies to phospho-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204), ERK1/2, and phospho-AKT (S473). Numbers beneath the bands show protein quantification after normalization to the α-tubulin loading control signal. Bar graphs on the right show data from 2 independent experiments. (B) AKT phosphorylation was measured by flow cytometry after anti-IgM stimulation of RFP+ Ramos cells expressing miR-28 (blue shaded histogram) or scramble RNA (red open histogram). The panel shows representative flow cytometry plots (top) and quantification of 4 independent experiments after normalization to controls (bottom). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. *P < .05, unpaired Student t test. (C) qRT-PCR of Bcl-2, NFKB2, and IKKB in miR-28 vs control Ramos RFP+ BL cells (n = 3). (D) Graphs show miR-28 expression plotted against transcript levels of NFKB2, IKKB, and BCL2 in human primary ABC-DLBCL lymphoma cohorts (data extracted from Iqbal et al26 ). R2 and P values are shown. (E) The MD-901 ABC-DLBCL cell line and the Raji and Ramos BL cell lines were transduced with pTRIPZ vectors encoding miR-28 (blue circles) or scramble RNA (red circles). RFP+ cells were cultured and counted every day throughout the culture period. Data are from at least 2 independent experiments. *P < .05, unpaired Student t test. (F) Primary splenic B cells were labeled with violet cell tracer, transduced with miR-28 or an empty control retroviral vector, and cultured in vitro with anti-IgM + IL-4. The bottom panel shows representative FACS histograms of GFP+ cells 2 days after retroviral transduction (red open line, control; blue shaded histogram, miR-28). The top panel shows quantification of the proportion of cells that have undergone 0 to 5 divisions (n = 2). *P < .05, unpaired Student t test. (G) FACS analysis of cell cycle in RFP+ miR-28– or control-transduced Ramos BL cells labeled with propidium iodide and 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU). Cell-cycle phases and BrdU incorporation in RFP+ miR-28– and control-transduced Ramos BL cells are quantified on the right (n = 4). (H-I) 7AAD and annexin V staining (n = 2) (H) and active caspase 3 staining (n = 6) (I) in RFP+ miR-28– and control-transduced Ramos BL cells. *P < .05, unpaired Student t test.

miR-28 regulates proliferation and cell death in lymphoma B cells by dampening the BCR signaling pathway. (A) Extracts of RFP+ Ramos BL cells, transduced with control or pre-miR-28–containing retroviral constructs, were immunoblotted with antibodies to phospho-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204), ERK1/2, and phospho-AKT (S473). Numbers beneath the bands show protein quantification after normalization to the α-tubulin loading control signal. Bar graphs on the right show data from 2 independent experiments. (B) AKT phosphorylation was measured by flow cytometry after anti-IgM stimulation of RFP+ Ramos cells expressing miR-28 (blue shaded histogram) or scramble RNA (red open histogram). The panel shows representative flow cytometry plots (top) and quantification of 4 independent experiments after normalization to controls (bottom). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. *P < .05, unpaired Student t test. (C) qRT-PCR of Bcl-2, NFKB2, and IKKB in miR-28 vs control Ramos RFP+ BL cells (n = 3). (D) Graphs show miR-28 expression plotted against transcript levels of NFKB2, IKKB, and BCL2 in human primary ABC-DLBCL lymphoma cohorts (data extracted from Iqbal et al26 ). R2 and P values are shown. (E) The MD-901 ABC-DLBCL cell line and the Raji and Ramos BL cell lines were transduced with pTRIPZ vectors encoding miR-28 (blue circles) or scramble RNA (red circles). RFP+ cells were cultured and counted every day throughout the culture period. Data are from at least 2 independent experiments. *P < .05, unpaired Student t test. (F) Primary splenic B cells were labeled with violet cell tracer, transduced with miR-28 or an empty control retroviral vector, and cultured in vitro with anti-IgM + IL-4. The bottom panel shows representative FACS histograms of GFP+ cells 2 days after retroviral transduction (red open line, control; blue shaded histogram, miR-28). The top panel shows quantification of the proportion of cells that have undergone 0 to 5 divisions (n = 2). *P < .05, unpaired Student t test. (G) FACS analysis of cell cycle in RFP+ miR-28– or control-transduced Ramos BL cells labeled with propidium iodide and 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU). Cell-cycle phases and BrdU incorporation in RFP+ miR-28– and control-transduced Ramos BL cells are quantified on the right (n = 4). (H-I) 7AAD and annexin V staining (n = 2) (H) and active caspase 3 staining (n = 6) (I) in RFP+ miR-28– and control-transduced Ramos BL cells. *P < .05, unpaired Student t test.

Next, we examined our RNA-Seq data for alterations in other miR-28–regulated BCR-related pathway components, focusing on NFKB2, IKKB, and BCL2. NFKB2 and IKKB are components of the NF-κB pathway, a major survival pathway downstream of the BCR and the most commonly altered gene pathway in lymphoid malignancies. Bcl-2 is an antiapoptotic protein induced by the BCR, and genetic gain-of-function BCL2 alterations are found in various mature B-cell malignancies. NFKB2, IKKB, and BCL2 were all downregulated in miR-28–expressing Ramos BL cells (supplemental Table 1; Figure 3C) and their expression correlated inversely with miR-28 expression in primary GC-derived lymphoma of the ABC-DLBCL subtype (Figure 3D) (data extracted from Iqbal et al26 ), which is known to specifically rely on chronic active BCR signaling for survival.29 Overall, these results show that miR-28 expression downregulates downstream effectors of BCR signaling, which play key roles in B-lymphocyte proliferation and survival, and whose expression is frequently upregulated in GC-derived malignancies.

To examine whether miR-28 expression regulates cell cycle and survival, we first expressed miR-28 in different human B-cell lymphomas and found that it reduced cell numbers in the MD901 ABC-DLBCL cell line and in Raji and Ramos BL cell lines, (Figure 3E), which is consistent with recent observations in other BL cell lines.25 To further expand these findings to primary B cells, we measured cell division in response to BCR stimulation. We found that spleen primary B cells transduced with miR-28 proliferated less than control B cells (Figure 3F). In addition, miR-28–expressing Ramos cultures contained a significantly lower proportion of proliferating cells than RFP+ control-transduced cultures (Figure 3G). miR-28 reexpression in BL cells also significantly increased apoptotic cell death (Figure 3H-I). Together, these results show that miR-28 expression impairs the proliferation and survival of both primary and tumor B lymphocytes most likely by dampening BCR signaling.

miR-28 suppresses tumor growth in GC-derived neoplasms

To assess the tumor suppressor activity of miR-28 in vivo, we first made use of xenograft models. Ramos cells were transduced with miR-28 or scramble lentiviral vectors, induced with Dox, and miR-28 RFP+ or control RFP+ lymphoma cells were injected subcutaneously into either flank of NSG mice (supplemental Figure 5). miR-28 expression significantly slowed the growth of xenograft tumors (Figure 4A) and markedly reduced tumor mass at end point (Figure 4B). miR-28–expressing Ramos BL tumors also contained fewer Ki67+ proliferating cells and Bcl-2–expressing cells and had a higher proportion of apoptotic active caspase 3+ cells (Figure 4C). These findings indicate that miR-28 reexpression impairs proliferation and survival of lymphoma cells. In a further test, we found that miR-28 reexpression in xenograft assays reduced tumor growth of an additional BL lymphoma cell line (Raji) and ABC-DLBCL (MD901) (Figure 4D), demonstrating that miR-28 antitumoral activity is not restricted to a single lymphoma type. These results show that miR-28 has tumor suppressor activity in both BL and DLBCL GC-derived lymphomas and interferes with lymphoma establishment in vivo.

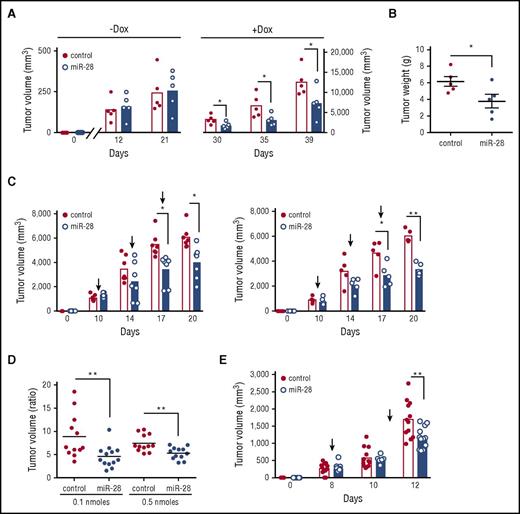

miR-28 expression impairs B-cell lymphoma growth in vivo. (A) Tumor volume in NSG mice injected with Ramos BL cells expressing miR-28 or scramble RNA (control). Ramos BL cells were transduced with pTRIPZ vectors encoding miR-28 precursor sequence (blue) or scrambled control (red) sequence and induced with Dox. RFP+ cells isolated by flow cytometry were injected subcutaneously into either flank of NSG mice. Dox was administered in the drinking water a week before injection and throughout the experiment. Tumors were measured at the indicated times and volume was calculated as volume (mm3) = (width [mm])2 × (length [mm])/2. Each circle represents an individual tumor. (B) Representative images of miR-28 or control xenograft tumors at endpoint (top) and weight (bottom) of miR-28 or control xenograft tumors at endpoint (26 days postinjection). (C) Ramos xenografts were prepared as described in panel A. Mice were euthanized 26 days postinjection and tumors were stained with anti-Ki67, anti-caspase-3, and anti-Bcl-2. Left panels show representative micrographs. Images were acquired at ×20 (Ki67 and caspase 3; ×40 in insets) or ×40 (Bcl2) magnification. Scale bars, 100 µm (Ki67) and 50 μm (Bcl-2). Right, quantification of active caspase 3 and Bcl-2 staining. (D) Tumor volume in NGS mice injected with MD-901 ABC-DLBCL or Raji BL cells expressing miR-28 or scramble RNA (control). MD-901 ABC-DLBCL, and Raji BL cells were transduced with pTRIPZ vectors encoding miR-28 precursor sequence (blue bars) or scrambled control sequence (red bars) and induced with Dox. *P < .05; ***P < .001, unpaired Student t test.

miR-28 expression impairs B-cell lymphoma growth in vivo. (A) Tumor volume in NSG mice injected with Ramos BL cells expressing miR-28 or scramble RNA (control). Ramos BL cells were transduced with pTRIPZ vectors encoding miR-28 precursor sequence (blue) or scrambled control (red) sequence and induced with Dox. RFP+ cells isolated by flow cytometry were injected subcutaneously into either flank of NSG mice. Dox was administered in the drinking water a week before injection and throughout the experiment. Tumors were measured at the indicated times and volume was calculated as volume (mm3) = (width [mm])2 × (length [mm])/2. Each circle represents an individual tumor. (B) Representative images of miR-28 or control xenograft tumors at endpoint (top) and weight (bottom) of miR-28 or control xenograft tumors at endpoint (26 days postinjection). (C) Ramos xenografts were prepared as described in panel A. Mice were euthanized 26 days postinjection and tumors were stained with anti-Ki67, anti-caspase-3, and anti-Bcl-2. Left panels show representative micrographs. Images were acquired at ×20 (Ki67 and caspase 3; ×40 in insets) or ×40 (Bcl2) magnification. Scale bars, 100 µm (Ki67) and 50 μm (Bcl-2). Right, quantification of active caspase 3 and Bcl-2 staining. (D) Tumor volume in NGS mice injected with MD-901 ABC-DLBCL or Raji BL cells expressing miR-28 or scramble RNA (control). MD-901 ABC-DLBCL, and Raji BL cells were transduced with pTRIPZ vectors encoding miR-28 precursor sequence (blue bars) or scrambled control sequence (red bars) and induced with Dox. *P < .05; ***P < .001, unpaired Student t test.

To determine if miR-28 can also impair the growth of established lymphomas, we injected miR-28–transduced Ramos cells into NSG mice before induction of the constructs with Dox. Tumors were allowed to grow until they reached a volume of 200 mm3, and only then was Dox administered in the drinking water (supplemental Figure 5B). We found that miR-28 replacement significantly slowed the growth rate of established Ramos BL tumors (Figure 5A-B). These results show the therapeutic potential of in vivo miR-28 delivery for the treatment of established GC-derived lymphomas.

miR-28 expression suppresses established human lymphomas. (A) Ramos BL cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding miR-28 or scramble RNA (control), and cells were injected subcutaneously, without induction, into NSG mice. Xenografts were left to establish for 21 days (until reaching ∼250 mm3), and miR-28 expression was then induced by Dox in the drinking water. Graphs show volumes of individual tumors and mean values at the indicated times before (−Dox) and after (+Dox) Dox administration (supplemental Figure 5B). (B) Tumor weights of miR-28 and control xenografts at 18 days after Dox treatment. (C) Intratumor administration with synthetic miR-28 mimic suppresses established BL tumors. Wild-type Ramos cells were injected subcutaneously into NSG mice; after xenografts were established (tumor volume >200 mm3), synthetic miR-28 mimic (blue bars) or scrambled control mimics (red bars) were administered intratumorally (supplemental Figure 5C). Graphs show tumor volumes at the indicated times in xenografts before and after treatment with 0.1 nmol (left) or 0.5 nmol (right) of miRNA mimic. (D) Endpoint-to-pretreatment volume ratios for the xenografts in panel C. (E) Ramos xenografts were established as in panel C and mice were treated by intravenous administration of 7 nmol miR-28 mimic (blue) or scrambled mimics (control, red circles) (supplemental Figure 5D). The graph shows tumor volumes at the indicated times. Each circle corresponds to an independent tumor. *P < .05; **P < .01, unpaired Student t test.

miR-28 expression suppresses established human lymphomas. (A) Ramos BL cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding miR-28 or scramble RNA (control), and cells were injected subcutaneously, without induction, into NSG mice. Xenografts were left to establish for 21 days (until reaching ∼250 mm3), and miR-28 expression was then induced by Dox in the drinking water. Graphs show volumes of individual tumors and mean values at the indicated times before (−Dox) and after (+Dox) Dox administration (supplemental Figure 5B). (B) Tumor weights of miR-28 and control xenografts at 18 days after Dox treatment. (C) Intratumor administration with synthetic miR-28 mimic suppresses established BL tumors. Wild-type Ramos cells were injected subcutaneously into NSG mice; after xenografts were established (tumor volume >200 mm3), synthetic miR-28 mimic (blue bars) or scrambled control mimics (red bars) were administered intratumorally (supplemental Figure 5C). Graphs show tumor volumes at the indicated times in xenografts before and after treatment with 0.1 nmol (left) or 0.5 nmol (right) of miRNA mimic. (D) Endpoint-to-pretreatment volume ratios for the xenografts in panel C. (E) Ramos xenografts were established as in panel C and mice were treated by intravenous administration of 7 nmol miR-28 mimic (blue) or scrambled mimics (control, red circles) (supplemental Figure 5D). The graph shows tumor volumes at the indicated times. Each circle corresponds to an independent tumor. *P < .05; **P < .01, unpaired Student t test.

Next, we assayed the antitumoral activity of a synthetic miR-28 mimic, an analog of the natural miRNA that is chemically modified to enhance stability and activity.30 First, wild-type Ramos BL cells were injected subcutaneously into NSG mice, tumors were allowed to reach a volume of 200 mm3, and mice were then given 3 intratumor mimic injections (supplemental Figure 5C). At both mimic doses and all time points analyzed, miR-28 mimic delayed the growth of established BL tumors (Figure 5C-D). We next tested the efficacy of miR-28 mimic when administered IV. Ramos BL xenografts were established as in the previous experiment, and mice were then given 2 intravenous injections with miR-28 mimic (supplemental Figure 5D). Mice treated with miR-28 mimic harbored notably smaller tumors than mice treated with control (scramble) mimics (Figure 5E). Histopathological analysis of kidney, liver, heart, and spleen of mice treated with intravenous miR-28 mimic showed no evidence of macroscopic or microscopic tissue alterations, indicating that this treatment does not have severe toxic effects (supplemental Figure 6).

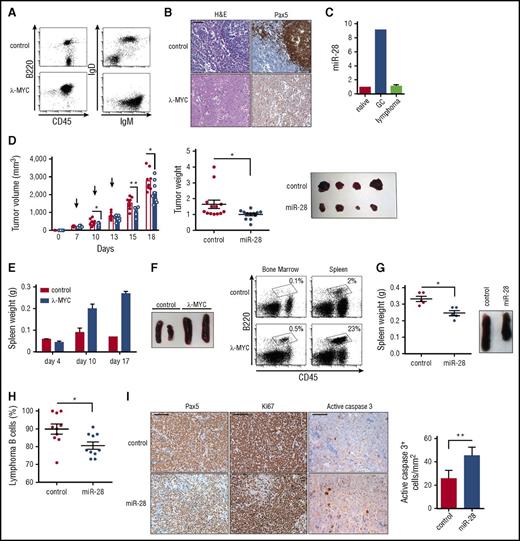

To study the therapeutic potential of miR-28 in primary lymphomas, we made use of the λ-MYC mouse model, which recapitulates many pathogenic features of human BL31 (Figure 6A-B). As expected, miR-28 expression was upregulated in normal GC B cells from λ-MYC mice. More remarkably, miR-28 expression in λ-MYC mice was lost upon B-cell transformation, in agreement with the loss of miR-28 in human B-cell neoplasms (Figure 6C). To assess the therapeutic potential of miR-28 replacement in primary lymphoma in vivo, we first injected lymphoma cells subcutaneously from enlarged spleens or lymph nodes of λ-MYC mice into NSG host mice and treated recipient mice with intratumoral administration of miR-28 or control mimic at either flank (supplemental Figure 5E). Growth was clearly reduced in tumors treated with miR-28 mimic compared with those treated with scramble mimic (Figure 6D). Finally, lymphoma cells from λ-MYC mice were injected IV into NSG recipients. In this model, mice receiving λ-MYC cells show spleen enlargement and a large expansion of B cells in the bone marrow, compared with mice receiving cells from control littermates (Figure 6E-F), which most likely reflects successful tumor engraftment. At days 10 and 14 after λ-MYC lymphoma transplant, NSG mice were IV injected with miR-28 mimic, and mice were euthanized for analysis 3 days later (supplemental Figure 5F). The spleens of miR-28–treated mice were notably smaller than those treated with control mimic (Figure 6G) and contained a lower proportion of lymphoma B cells (Figure 6H). Indeed, intravenous miR-28 mimic reduced the proportion of B lymphoma cells and proliferating Ki67+ cells in spleen and increased the numbers of caspase 3+ apoptotic cells. Together, these results demonstrate that therapeutic strategies that promote miR-28 reexpression have the potential to impair B-cell tumor growth in vivo by diminishing lymphoma proliferation and promoting cell death.

miR-28 expression suppresses established primary lymphomas. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of lymph nodes from control and λ-MYC littermate mice. (B) Representative histochemistry images of control and λ-MYC littermate spleens. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of miR-28 in naïve, GC, and lymphoma cells from λ-MYC mice. (D) Cells from enlarged spleen or lymph nodes from λ-MYC mice were injected subcutaneously into NSG mice. Two λ-MYC primary tumors were used as donors in 2 independent experiments to inject a total of 12 NSG recipient mice in both flanks. Once tumors were detectable (>200 mm3), each mouse was injected intratumorally with miR-28 mimic (blue) in 1 flank and control mimic (white bars, red circles) in the other (supplemental Figure 5E) in 3 injections. Tumor growth was monitored throughout the experiment (left graph; arrows indicate mimic injections, a representative experiment is shown) and at endpoint (central graph, data from 2 independent experiments, normalized to the average value; right, representative image). Each symbol represents an individual engrafted tumor. (E-F) Lymph node cells from control and λ-MYC littermate mice were injected IV into NSG recipients. (E) Spleen weights of NSG mice euthanized at the indicated posttransplant times. (F) Representative flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow or spleen from NSG mice 10 days after transplant with control or λ-MYC cells. Representative spleens are shown to the right. (G-I) Cells from enlarged λ-MYC spleen or lymph nodes were injected IV into NSG recipient mice; 10 days later, mice received intravenous injections of miR-28 or control mimics (supplemental Figure 5F). Two independent donor primary tumors were used in 2 independent experiments to inject a total of 10 recipient mice for control mimic treatment and 10 recipient mice for miR-28 mimic treatment. (G) Spleen weights of transplanted NGS mice (left) and images (right) after treatment with miR-28 or control mimics from 1 representative experiment. (H) Proportion of spleen B cells in transplanted NSG mice after treatment with miR-28 or control mimics (data from 2 independent experiments with 2 λ-MYC tumors normalized to the tumor with the maximum proportion of B cells). (I) Spleens from NSG mice transplanted with λ-MYC and treated with control or miR-28 mimic were stained with the indicated antibodies. Scale bar 100 µm for Pax5 and Ki67 and 25 µm for active caspase 3. Quantification of caspase 3 staining is shown on the right. *P < .05, **P < .01 unpaired Student t test.

miR-28 expression suppresses established primary lymphomas. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of lymph nodes from control and λ-MYC littermate mice. (B) Representative histochemistry images of control and λ-MYC littermate spleens. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of miR-28 in naïve, GC, and lymphoma cells from λ-MYC mice. (D) Cells from enlarged spleen or lymph nodes from λ-MYC mice were injected subcutaneously into NSG mice. Two λ-MYC primary tumors were used as donors in 2 independent experiments to inject a total of 12 NSG recipient mice in both flanks. Once tumors were detectable (>200 mm3), each mouse was injected intratumorally with miR-28 mimic (blue) in 1 flank and control mimic (white bars, red circles) in the other (supplemental Figure 5E) in 3 injections. Tumor growth was monitored throughout the experiment (left graph; arrows indicate mimic injections, a representative experiment is shown) and at endpoint (central graph, data from 2 independent experiments, normalized to the average value; right, representative image). Each symbol represents an individual engrafted tumor. (E-F) Lymph node cells from control and λ-MYC littermate mice were injected IV into NSG recipients. (E) Spleen weights of NSG mice euthanized at the indicated posttransplant times. (F) Representative flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow or spleen from NSG mice 10 days after transplant with control or λ-MYC cells. Representative spleens are shown to the right. (G-I) Cells from enlarged λ-MYC spleen or lymph nodes were injected IV into NSG recipient mice; 10 days later, mice received intravenous injections of miR-28 or control mimics (supplemental Figure 5F). Two independent donor primary tumors were used in 2 independent experiments to inject a total of 10 recipient mice for control mimic treatment and 10 recipient mice for miR-28 mimic treatment. (G) Spleen weights of transplanted NGS mice (left) and images (right) after treatment with miR-28 or control mimics from 1 representative experiment. (H) Proportion of spleen B cells in transplanted NSG mice after treatment with miR-28 or control mimics (data from 2 independent experiments with 2 λ-MYC tumors normalized to the tumor with the maximum proportion of B cells). (I) Spleens from NSG mice transplanted with λ-MYC and treated with control or miR-28 mimic were stained with the indicated antibodies. Scale bar 100 µm for Pax5 and Ki67 and 25 µm for active caspase 3. Quantification of caspase 3 staining is shown on the right. *P < .05, **P < .01 unpaired Student t test.

Discussion

Our study addresses the role of miR-28 in the context of the GC and the establishment and maintenance of GC-derived neoplasms. Using miR-28 gain-of-function assays, we found that miR-28 expression negatively regulates CSR and proliferation, whereas loss-of-function miR-28 assays showed increased memory B- and plasma cell (PC)-cell generation in vivo. We hypothesize that miR-28–mediated regulation of cell proliferation and survival limits or terminates the GC reaction in vivo, thereby acting as a brake on B-cell transformation. Supporting this idea, we detected progressively increasing miR-28 expression during the GC reaction and found that the loss of miR-28 expression is a frequent event in mature B-cell neoplasms, both in man and mouse.

Although the mechanism regulating miR-28 expression in GCs remains to be determined, the lack of miR-28 upregulation in B cells stimulated in vitro (Kuchen et al21 and our unpublished observations) hints at events linked to T cell–dependent stimulation in vivo. Further research is merited into the events leading to miR-28 downregulation in a variety of B-cell neoplasms, including CLL, DLBCL, and BL; however, genomic loss and transcriptional regulation mechanisms are both likely to be important.25,26

To identify the genes regulated by miR-28 in B cells, we combined quantitative transcriptome and proteome analyses. We found a significant overlap between the mRNA targets found in our transcriptome analysis and those mRNAs showing the highest miR-28–induced fold changes in a previous report.25 In our study, we believed that the combination of transcriptome and proteome approaches was the preferable choice for miRNA target identification, to allow the detection of miR-28 activity both at the level of mRNA stability reduction and at the level of translation inhibition.32,33 Importantly, this strategy has led to the finding that miR-28 significantly alters the BCR signaling network, the key signaling pathway regulating B-cell proliferation and cell death. Dampened BCR signaling in miR-28–expressing B cells is confirmed by reduced phosphorylation of key mediators of BCR signaling such as AKT and ERK and by reduced expression of the NF-κB mediators NF-κB2 and IKKβ and the antiapoptotic effector Bcl-2. Therefore, our data support the notion that miR-28 limits the strength of BCR signaling, promoting a deficient or slower proliferative activity together with impaired survival, which in turn could account for the defect in CSR.34

BCR signaling plays a central role in the survival of neoplastic B cells. This pivotal signaling pathway for B-cell physiology is hijacked by tumor cells, where BCR gain-of-function mutations are very frequent (reviewed in Shaffer et al1 ). Indeed, several B-cell lymphomas, such as BL35,36 and ABC-DLBCL,29,37 rely on BCR signaling to sustain lymphoma growth. Accordingly, various therapeutic strategies for mature B-cell lymphoma are based on the inhibition of key BCR signaling intermediates,38 including NF-κB and IKKβ39,40 and the antiapoptotic effector Bcl-2 (reviewed in Braun et al41 ). Although further experiments are required to define the exact regulation of BCR by miR-28, we have found that miR-28 expression correlates inversely with the levels of NFKB2, BCL2, and IKKB2 specifically in ABC-DLBCL. This, together with the finding that ABC-DLBCL cases show a dramatic loss of miR-28,26 suggests that ABC-DLBCL might be especially amenable to miR-28–based therapy.

Our miR-28 replacement experiments in a variety of in vivo lymphoma models confirm that miR-28 has antitumor activity. Our results show that prophylactic and therapeutic lentiviral deliveries of miR-28 interfere with tumor establishment and growth both in BL and in DLBCL xenografts. These in vivo lymphoma models are widely used for preclinical antilymphoma drug testing.42 In our work, we have demonstrated that miR-28 has antitumor activity not only in xenografts of human lymphoma cell lines, but also in different settings of murine primary lymphoma using λ-MYC mice, where B-cell transformation is also linked to miR-28 loss. miR-28 reexpression impairs proliferation and survival pathways in lymphoma cells and suggests that the increased tumor cell death could be due to loss of Bcl-2, perhaps by dampening BCR signaling. This hypothesis fits with the general idea that BCR signaling is central to the establishment and maintenance of GC-derived lymphomas.29,37,41,43-47 However, our profiling results are also compatible with contributions from other miR-28 targets regulating alternative pathways of proliferation and cell survival in lymphoma cells, or with NFκB and Bcl-2 being activated through signaling pathways other than the BCR.

In addition, we were also able to block lymphoma growth using synthetic mimics, which are thought to be the safest route for therapeutic miRNA reintroduction. In recent years, the functional impact of miRNAs on cancer development has made them very attractive candidates for therapeutic strategies (reviewed in Braicu et al48 and Bader et al49 ). miRNAs potentially confer a high degree of specificity because of their intrinsic sequence-dependent target definition. Moreover, miRNAs target gene networks rather than individual genes, potentially making miRNA-based therapy less susceptible to the development of resistance. Finally, therapies based on replacing the normal levels of a tumor repressor miRNA that have been lost during tumorigenesis are expected to be significantly less toxic than antitumor treatments (reviewed in Taylor and Schiemann18 and Nana-Sinkam and Croce19 ). In line with the targeted nature of this approach, our data suggest that the toxicity of miR-28 will be considerably lower than current strategies for the treatment of B-cell neoplasms.

From the therapeutic standpoint, it is important to identify drugs that can improve the efficacy and reduce the toxicity of standard antilymphoma therapy. This is particularly relevant for BL and DLBCL, which are often refractory to conventional chemotherapy.50,51 Taken together, the results of this study reveal the therapeutic potential of miR-28 and provide a rationale for the initiation of clinical trials of miR-28–based therapies to treat B-cell NHL.

The RNAseq data accession number is GSE81236. Proteomics data reported in this article have been deposited in the PeptideAtlas database (accession number PASS00874).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the B Cell Biology Laboratory for helpful discussions; F. Sanchez-Cabo and M.J. Gómez for help with RNAseq and statistical analyses; S. Montes, M.A. Piris, and N. Martinez for helpful advice on lymphoma samples; A. de Molina for pathology assessments; J.M. Ligos for flow cytometry advice; and S. Bartlett for English editorial support.

This work was supported by a Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad’s research training program (Formación de Personal Investigador [FPI]) fellowship (N.B.-I.); the Ramón y Cajal program (RYC-2009-04503) funded by the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte and the European Research Council Proof of Concept program (HEAL-BY-MIRNA 713728) (V.G.d.Y.); the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovaculares (CNIC) (A.F.A.-P., S.M.M., A.R.R.); the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (SAF2010-21394, SAF2013-42767-R), the European Research Council Starting Grant program (BCLYM-207844), and Proof of Concept program (HEAL-BY-MIRNA 713728) (A.R.R.); the People Programme-Marie Curie Actions (FP7-PIIF-2012-328177), Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO; SAF2013-45787-R), and Gobierno de Navarra (GN-106/2014) (S.R.); and the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (BIO2012-37926 and BIO2015-67580-P), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria [FIS] grants PRB2 [IPT13/0001, ProteoRed], the Fundación La Marato TV3, and Redes temáticas de investigación cooperativa en salud [RETICS] [RD12/0042/00056, RIC]) (J.V.). This work has been cofunded by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) funds. The CNIC is supported by the and the Pro CNIC Foundation and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (MINECO award SEV-2015-0505).

Authorship

Contribution: V.G.d.Y. and A.R.R. wrote the manuscript; N.B.-I., V.G.d.Y., and A.R.R. designed the research and analyzed data; N.B.-I., V.G.d.Y., A.F.A.-P., and S.M.M. performed experiments; J.A.L.d.O. and J.V. performed and analyzed iTRAQ experiments; and S.R. provided lymphoma expertise and samples.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A PCT patent application entitled “MiRNA compositions for the treatment of mature B-cell neoplasms” was filed on May 13, 2016, with the European Patent Office designated as International Search Authority and claiming priority of the European patent application EP15382 249.9, filed 1 year before.

Correspondence: Almudena R. Ramiro, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, Melchor Fernandez Almagro 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain; e-mail: aramiro@cnic.es; and Virginia G. de Yébenes, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, Melchor Fernandez Almagro 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain; e-mail: vgarciay@cnic.es.

References

Author notes

N.B.-I. and V.G.d.Y. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 4. miR-28 expression impairs B-cell lymphoma growth in vivo. (A) Tumor volume in NSG mice injected with Ramos BL cells expressing miR-28 or scramble RNA (control). Ramos BL cells were transduced with pTRIPZ vectors encoding miR-28 precursor sequence (blue) or scrambled control (red) sequence and induced with Dox. RFP+ cells isolated by flow cytometry were injected subcutaneously into either flank of NSG mice. Dox was administered in the drinking water a week before injection and throughout the experiment. Tumors were measured at the indicated times and volume was calculated as volume (mm3) = (width [mm])2 × (length [mm])/2. Each circle represents an individual tumor. (B) Representative images of miR-28 or control xenograft tumors at endpoint (top) and weight (bottom) of miR-28 or control xenograft tumors at endpoint (26 days postinjection). (C) Ramos xenografts were prepared as described in panel A. Mice were euthanized 26 days postinjection and tumors were stained with anti-Ki67, anti-caspase-3, and anti-Bcl-2. Left panels show representative micrographs. Images were acquired at ×20 (Ki67 and caspase 3; ×40 in insets) or ×40 (Bcl2) magnification. Scale bars, 100 µm (Ki67) and 50 μm (Bcl-2). Right, quantification of active caspase 3 and Bcl-2 staining. (D) Tumor volume in NGS mice injected with MD-901 ABC-DLBCL or Raji BL cells expressing miR-28 or scramble RNA (control). MD-901 ABC-DLBCL, and Raji BL cells were transduced with pTRIPZ vectors encoding miR-28 precursor sequence (blue bars) or scrambled control sequence (red bars) and induced with Dox. *P < .05; ***P < .001, unpaired Student t test.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/17/10.1182_blood-2016-08-731166/4/m_blood731166f4.jpeg?Expires=1769228344&Signature=VbL~sIBXZDwjdnNLIu396FJZ7-k26la-cVRMzbKAgbAyAYWXZkABuK7LOetIjcHxrGeKbTDRcf~-RgkNJfrUn6s-Rw84DwgRSjsU~14aJPQVn0M1fgOgQcpwPT5FXLKAKgsa~eFw71pUpMexue8stlmIOJpxVqWJd13Mx-giNuGT3YS4-gkOmt5YIVjZbgm51d4T4P4A7WL5A2g08AOUoOctFC31SfrXrbgdEx0HgjYVAFVP4RH5o-4Qy1rGMeYg~nsgpfKZVGU3ZH3zlWi4E5N7pTjoblUgXshjCg-xQIidD~xhCb76CpWAEyYR9Gzt1oRhomzqDesa-Jvom9WCNg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)