Key Points

IFPs can convert signals from inhibitory ligands into activating signals.

Costimulation was most effectively achieved by engineering the IFP to promote the ability to localize in the immunological synapse.

Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the most common adult acute leukemia in the United States, has the poorest survival rate, with 26% of patients surviving 5 years. Adoptive immunotherapy with T cells genetically modified to recognize tumors is a promising and evolving treatment option. However, antitumor activity, particularly in the context of progressive leukemia, can be dampened both by limited costimulation and triggering of immunoregulatory checkpoints that attenuate T-cell responses. Expression of CD200 (OX2), a negative regulator of T-cell function that binds CD200 receptor (CD200R), is commonly increased in leukemia and other malignancies and is associated with poor prognosis in leukemia patients. To appropriate and redirect the inhibitory effects of CD200R signaling on transferred CD8+ T cells, we engineered CD200R immunomodulatory fusion proteins (IFPs) with the cytoplasmic tail replaced by the signaling domain of the costimulatory receptor, CD28. An analysis of a panel of CD200R-CD28 IFP constructs revealed that the most effective costimulation was achieved in IFPs containing a dimerizing motif and a predicted tumor–T-cell distance that facilitates localization to the immunological synapse. T cells transduced with the optimized CD200R-CD28 IFPs exhibited enhanced proliferation and effector function in response to CD200+ leukemic cells in vitro. In adoptive therapy of disseminated leukemia, CD200R-CD28–transduced leukemia-specific CD8 T cells eradicated otherwise lethal disease more efficiently than wild-type cells and bypassed the requirement for interleukin-2 administration to sustain in vivo activity. The transduction of human primary T cells with the equivalent human IFPs increased proliferation and cytokine production in response to CD200+ leukemia cells, supporting clinical translation. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01640301.

Introduction

Adoptive immunotherapy with engineered T cells has shown promising clinical benefit, particularly in acute lymphocytic leukemia with T cells expressing a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) specific for the cell surface protein CD19.1,2 T cells can alternatively be engineered to express a tumor-specific T-cell receptor (TCR), which greatly expands the breadth of target antigens by including intracellular (ic) proteins, such as transcription factors, that often drive the oncogenic phenotype. We demonstrated that CD8+ T cells specific for WT1, a transcription factor overexpressed in many malignancies,3,4 exhibit antileukemic activity in patients,5 and we have ongoing trials with CD8+ T cells transduced with a high affinity WT1-specific TCR in patients with leukemia,6 lung cancer, or mesothelioma (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier #NCT01640301 and #NCT02408016). T-cell activation with associated proliferation and survival requires a costimulatory signal concurrent with triggering the antigen receptor.7 Unlike CARs, which can include a costimulatory domain, cells with introduced TCRs require independent triggering of a costimulatory receptor. However, tumor cells generally express few if any ligands for costimulatory receptors and commonly upregulate inhibitory ligands that interfere with costimulation and T-cell activation.8 Strategies to overcome inhibitory signaling and increase costimulation/activation are thus being actively pursued to promote T-cell antitumor activity.9

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has a 26% 5-year survival rate with current therapies.10 Because T cells naturally traffic to hematopoietic sites where AML localizes, T-cell therapy has significant potential. However, the overexpression of inhibitory molecules by AML cells represents a substantive barrier to success.11 The type-1 membrane protein, CD200, binds to the T-cell inhibitory CD200 receptor (CD200R),12 and CD200 expression is observed in AML and other malignancies, including myeloma, ovarian, and prostate cancers.13-15 Importantly for targeted therapy, increased CD200 expression has been detected in cancer stem cells and leukemia stem cells, the small subpopulation with high proliferative capacity that initiates and maintains disease and is resistant to radiation and chemotherapy.16-19 CD200R signaling inhibits the function of T cells20,21 and other immune cells, including natural killer cells,22 and high CD200 expression has been linked with poor outcomes in AML.17

Synthetic biology affords the opportunity to engineer T cells not just with tumor-reactive receptors, but also with molecules that abrogate negative signals and provide missing activating signals. An immunomodulatory fusion protein (IFP) with a PD-1 ectodomain has been shown to be capable of providing costimulatory signals,23 but the principles for designing IFPs to optimize costimulatory signals have not been defined. To overcome inhibitory CD200R signaling in CD8+ T cells, we engineered a panel of IFPs designed to elucidate these principles consisting of the CD200R ectodomain fused to an ic costimulatory signaling domain and tested for enhanced T-cell function in murine and human studies.

Methods

Mice, cell lines, and antibodies

C57BL/6J (B6) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. TCRgag transgenic mice express a TCR in CD8+ T cells that is specific for the Friend virus gag epitope (peptide CCLCLTVFL)24 of the B6 Friend virus–induced erythroleukemia (FBL ).25 All animal studies were approved under a University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol (#2013-01). Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were purchased from eBioscience or BioLegend. Phospho-LCK (pLCK Tyr394; R&D Systems) was detected by ic staining and secondary labeling with anti-mouse phycoerythrin.

Microscopy

CD200R IFP-transduced, in vitro–expanded effector TCRgag cells were mixed with FBL at an effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 10:1 in 15 mL, and then incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes and loaded on a μ-Slide VI.4 chamber (Ibidi) for 15 minutes. Slides were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 4 minutes. Cells were then washed and stained with CD200R-phycoerythrin, CD200-Alexa Fluor 660, and cholera toxin B subunit (CTxB)-Alexa Fluor 488. Slides were imaged at 60× using a DeltaVision Elite fluorescent microscope and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Adoptive immunotherapy of disseminated FBL leukemia

B6 mice were injected with 4 × 106 FBL cells intraperitoneally (i.p.). After 5 days to allow the FBL to disseminate, mice received 180 mg/kg cyclophosphamide i.p. 6 hours before the transfer of the effector T cells. For survival studies, 105 TCRgag T cells previously stimulated 1 to 3 times in vitro were transferred into tumor-bearing mice. To assess short-term proliferation and accumulation, 2 × 106 of IFP-transduced or empty vector control–transduced T cells were injected into tumor-bearing mice, and the mice were euthanized for analysis 3 or 15 days later. CD8+ T cells were isolated by negative selection using the EasySep Mouse CD8+ T Cell Enrichment Kit (STEMCELL). Mice were regularly monitored for increasing tumor burden and euthanized if the evidence of tumor progression predicted that mortality would occur within 24 to 48 hours.

Clinical protocol

All clinical investigations were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles. Protocol 2498 was approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Institutional Review Board and the US Food and Drug Administration. The trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01640301.

Generation of human constructs and lentiviral transduction

To generate lentiviruses, 293T/17 cells (3 × 106 cells/plate) were transduced with human constructs in the pRRLSIN plasmid and the packaging plasmids pMDLg/pRRE, pMD2-G, and pRSV-REV using Effectene (Qiagen). Culture media was changed on day 1 posttransfection, virus-containing supernatant was collected on days 2 and 3, and aliquots were frozen for future use.

After obtaining informed consent, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were harvested from normal HLA-A2+ donors. CD8+ T cells were purified using Miltenyi magnetic beads and stimulated with Human T cell Expander CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Life Technologies) and 50 IU/mL of interleukin-2 (IL-2). Four hours after stimulation, T cells were transduced by spinfection of 5 to 10 × 106 cells with 2 mL of lentiviral supernatant at 1000g for 90 minutes at 32°C. T cells were restimulated every 10 to 14 days with a rapid expansion protocol, as previously described.26

Results

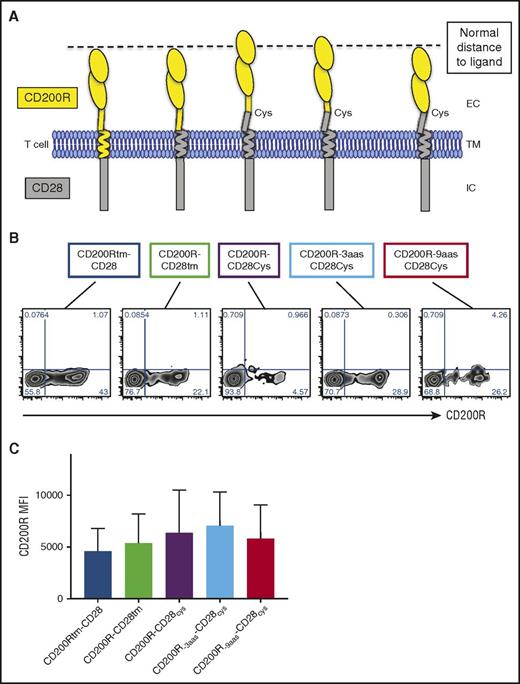

CD200R-CD28 IFPs can be expressed by primary T cells

To determine the design requirements of the fusion protein to deliver an effective costimulatory signal, we constructed a panel of CD200-targeted IFPs incorporating different components of the CD200R extracellular (ec) and transmembrane (tm) domains fused with components of the CD28 ec, tm, and ic domains (Figure 1A). CD28 signaling naturally occurs in the immunological synapse (IS), where CD28 is recruited with its ligand to amplify TCR signals and lower the threshold of activation.7,27 Similarly, CD200R and its ligand CD200 are sized to enter the IS and deliver inhibitory signals.12 The spatial distance between the T cell and antigen-presenting cell (APC) is shortest within the IS, and molecules with large ectodomains are excluded, thus we predicted that the constructs that best approximated this cell-to-cell spacing would colocalize with the TCR within the IS and deliver an effective costimulatory signal. The first 2 constructs contained the entire CD200R ectodomain and ic region of CD28: the first with the CD200Rtm region (CD200Rtm-CD28), and the second with the CD28tm region (CD200R-CD28tm). The next 3 constructs extended the CD28tm into the ec space to incorporate the membrane proximal cysteine (CD28cys) that promotes CD28 homodimerization and enhances native CD28 signaling.28 To compensate for length added by the 9 amino acids (aas) of the ec CD28 domain, the ec region of CD200R in CD200R-9aas-CD28cys was truncated by 9 aas, whereas the ec domain of CD200R-3aas-CD28cys was truncated by 3 aas to preserve a potentially structurally important N-linked glycosylation site. Thus, CD200Rtm-CD28, CD200R-CD28tm, and CD200R-9aas-CD28cys theoretically best approximate the native short spatial distance of CD200R-CD200 (between the T cell and the APC).

CD200R-CD28 constructs are expressed at high levels on primary murine CD8+T cells. (A) Schematic representation of CD200R-CD28 constructs. CD200Rtm-CD28 contains CD200R ec and tm domains and a CD28 ic signaling domain. CD200R-CD28tm contains the ec domain of CD200R and the tm and ic domains of CD28. The remaining 3 constructs also incorporate a portion of the ec domain of CD28 to the tm-proximal cysteine to promote multimerization and enhance CD28 signaling. To account for the extra 9 ec aas, CD200R-3aas-CD28cys has a truncated portion of CD200R that removes 3 membrane-proximal aas, but preserves an N-linked glycosylation site. CD200R-9aas-CD28cys has an extracellular portion of CD200R that is truncated 9 membrane-proximal aas. The first, second, and last constructs are predicted to approximate the spatial distance between the T cell and an APC, as indicated by the dashed line. (B) Transgenic expression of CD200R-CD28 constructs on TCRgag T cells as detected by anti-CD200R antibody. (C) Expression of CD200R in transduced TCRgag T cells as in panel B, expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Cumulative results of 6 independent experiments (P = not significant).

CD200R-CD28 constructs are expressed at high levels on primary murine CD8+T cells. (A) Schematic representation of CD200R-CD28 constructs. CD200Rtm-CD28 contains CD200R ec and tm domains and a CD28 ic signaling domain. CD200R-CD28tm contains the ec domain of CD200R and the tm and ic domains of CD28. The remaining 3 constructs also incorporate a portion of the ec domain of CD28 to the tm-proximal cysteine to promote multimerization and enhance CD28 signaling. To account for the extra 9 ec aas, CD200R-3aas-CD28cys has a truncated portion of CD200R that removes 3 membrane-proximal aas, but preserves an N-linked glycosylation site. CD200R-9aas-CD28cys has an extracellular portion of CD200R that is truncated 9 membrane-proximal aas. The first, second, and last constructs are predicted to approximate the spatial distance between the T cell and an APC, as indicated by the dashed line. (B) Transgenic expression of CD200R-CD28 constructs on TCRgag T cells as detected by anti-CD200R antibody. (C) Expression of CD200R in transduced TCRgag T cells as in panel B, expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Cumulative results of 6 independent experiments (P = not significant).

The constructs were inserted into the pMP71 retroviral vector and used to transduce primary mouse splenocytes stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. Five days posttransduction, CD8+ T cells were analyzed for IFP expression by flow cytometry (Figure 1B). Transduction efficiency ranged from 5% to 43%, with no significant difference in the mean fluorescence intensity of transduced cells (Figure 1C; P = not significant).

CD200R-CD28 constructs promote proliferation, accumulation, and effector function of transduced T cells stimulated by CD200+ tumor target cells in vitro

CD28 signaling promotes the proliferation and survival of T cells stimulated via the TCR.7 To determine if CD200R-CD28 IFPs improve proliferation, we transduced naive CD8+ TCR transgenic T cells (TCRgag cells) specific for an epitope derived from FBL leukemia29 and expanded the T cells in vitro in the presence of IL-2 for 2 to 3 stimulation cycles to generate effector T cells, similar to protocols for human adoptive immunotherapy using TCR-transduced cells.30 We labeled effector T cells with CellTrace Violet (CTV) and stimulated cells with either FBL, which does not naturally express CD200 (CD200– FBL; Figure 2A, upper panels) or an FBL line transduced to express CD200 (CD200+ FBL; Figure 2A, lower panels). At a low 25:1 T cell–to-FBL ratio, GFP-control transduced T cells (blue lines) exhibited minimal proliferation in response to CD200– or CD200+ FBL. In contrast, 4 of the 5 tested constructs (red lines) improved proliferation in response to CD200+ FBL, but not CD200– FBL. To normalize across experiments, the ratio of the percentage of divided CD200R+ to the percentage of divided CD200R– for 3 independent experiments was calculated (Figure 2B; n = 3). Although this analysis revealed that several constructs improved proliferation, T cells transduced with the largest ectodomain, CD200R-CD28cys, consistently did not, and we omitted this construct from further testing.

CD200R-CD28 constructs promote proliferation, accumulation, and effector function of transduced T cells stimulated by CD200+tumor target cells in vitro. Splenocytes from naive TCRgag mice were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL), anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL), and recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2, 100 U/mL) and transduced with retroviral supernatant for 2 days. Cells were restimulated every 7 days with irradiated FBL and splenocytes and cultured with rhIL-2 (50 U/mL) for ≤3 stimulations. T cells were used for assays 5 to 7 days after the last stimulation. (A) Proliferation of CD200R-CD28 (red lines) and GFP empty vector control (blue lines) TCRgag T cells as measured by CTV dilution after stimulation with CD200– FBL (upper panels) or CD200+ FBL (lower panels) at a low E:T ratio of 25:1 for 3 days. (B) Cumulative proliferation of cells depicted in panel A. Proliferation was normalized across experiments by assessing the proportion of divided CD200R-CD28+ T cells relative to empty vector–transduced T cells (% dividedCD200R+/% dividedCD200R– [n = 3]). (C) Enrichment of transduced TCRgag T cells in a mixed population including nontransduced TCRgag T cells after 3 weekly cycles of stimulation with irradiated CD200+ FBL and splenocytes (n = 4-5/group). **P < .01 (Student t test). (D) Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester cytotoxicity assay. TCRgag T cells were transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys (red bars) or mock-transduced cells (black bars). Effector TCRgag T cells were incubated at the indicated effector to target ratio with a 1:1 mix of CD200+ FBL and nonspecific EL4 control targets for 4 hours. The relative frequency of FBL vs control tumor cells was determined by flow cytometry, and the percentage of specific lysis was determined by the frequency of FBL cells after T-cell culture relative to FBL incubated without T cells; cumulative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 (Student t test). (E) Cytokine production of TCRgag T cells transduced with GFP control (black lines) or CD200R IFP (red lines) relative to unstimulated T cells (gray filled) after coculture at a 1:1 ratio with CD200– (upper histograms) or CD200+ (lower histograms) FBL for 4 hours in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Cells were fixed, permeabilized, stained for ic cytokines, and assessed by flow cytometry. (F) Summary of panel E. Stacked bar charts of cytokine production in TCRgag T cells in response to CD200– (left) or CD200+ (right) FBL stimulation at a 1:1 ratio. Data are presented as no cytokine (white), 1 cytokine (light gray), or 2+ cytokine (dark gray) production; cumulative results of 3 independent experiments. (G) Visualization of CD200R localization within T cell-FBL conjugates. TCRgag in vitro expanded effector T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys (upper panels) or CD200R-CD28cys (lower panels) were cocultured with CD200+ FBL at an E:T ratio of 10:1 at 37°C for 20 minutes to allow conjugate formation. Conjugates were loaded on a μ-Slide VI 0.4 chamber (Ibidi) for an additional 15 minutes. Cells were fixed and stained for CD200R (first panels), CD200 (second panels), and lipid rafts by CTxB (third panels; overlay in fourth panels). Conjugates were imaged by microscopy on the DeltaVision Elite (60×) and analyzed using ImageJ software. (H) Quantification of conjugates that exhibit CD200R staining within the synapse, as in panel G, expressed as the percentage of total T cell-FBL conjugates. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation from 2 separate experiments for a total of 50 conjugates assessed. (I) pLCK Y394 expression of TCRgag T cells. T cells were transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys (red line), CD200R-CD28cys (blue line), or GFP control (black line) and were left unstimulated (upper left histogram and gray filled in other histograms) or stimulated for 10 minutes with PMA/ionomycin, CD200– FBL, or CD200+ FBL, as indicated. FBL stimulation was performed at an E:T ratio of 10:1; representative of 2 independent experiments.

CD200R-CD28 constructs promote proliferation, accumulation, and effector function of transduced T cells stimulated by CD200+tumor target cells in vitro. Splenocytes from naive TCRgag mice were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL), anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL), and recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2, 100 U/mL) and transduced with retroviral supernatant for 2 days. Cells were restimulated every 7 days with irradiated FBL and splenocytes and cultured with rhIL-2 (50 U/mL) for ≤3 stimulations. T cells were used for assays 5 to 7 days after the last stimulation. (A) Proliferation of CD200R-CD28 (red lines) and GFP empty vector control (blue lines) TCRgag T cells as measured by CTV dilution after stimulation with CD200– FBL (upper panels) or CD200+ FBL (lower panels) at a low E:T ratio of 25:1 for 3 days. (B) Cumulative proliferation of cells depicted in panel A. Proliferation was normalized across experiments by assessing the proportion of divided CD200R-CD28+ T cells relative to empty vector–transduced T cells (% dividedCD200R+/% dividedCD200R– [n = 3]). (C) Enrichment of transduced TCRgag T cells in a mixed population including nontransduced TCRgag T cells after 3 weekly cycles of stimulation with irradiated CD200+ FBL and splenocytes (n = 4-5/group). **P < .01 (Student t test). (D) Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester cytotoxicity assay. TCRgag T cells were transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys (red bars) or mock-transduced cells (black bars). Effector TCRgag T cells were incubated at the indicated effector to target ratio with a 1:1 mix of CD200+ FBL and nonspecific EL4 control targets for 4 hours. The relative frequency of FBL vs control tumor cells was determined by flow cytometry, and the percentage of specific lysis was determined by the frequency of FBL cells after T-cell culture relative to FBL incubated without T cells; cumulative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 (Student t test). (E) Cytokine production of TCRgag T cells transduced with GFP control (black lines) or CD200R IFP (red lines) relative to unstimulated T cells (gray filled) after coculture at a 1:1 ratio with CD200– (upper histograms) or CD200+ (lower histograms) FBL for 4 hours in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Cells were fixed, permeabilized, stained for ic cytokines, and assessed by flow cytometry. (F) Summary of panel E. Stacked bar charts of cytokine production in TCRgag T cells in response to CD200– (left) or CD200+ (right) FBL stimulation at a 1:1 ratio. Data are presented as no cytokine (white), 1 cytokine (light gray), or 2+ cytokine (dark gray) production; cumulative results of 3 independent experiments. (G) Visualization of CD200R localization within T cell-FBL conjugates. TCRgag in vitro expanded effector T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys (upper panels) or CD200R-CD28cys (lower panels) were cocultured with CD200+ FBL at an E:T ratio of 10:1 at 37°C for 20 minutes to allow conjugate formation. Conjugates were loaded on a μ-Slide VI 0.4 chamber (Ibidi) for an additional 15 minutes. Cells were fixed and stained for CD200R (first panels), CD200 (second panels), and lipid rafts by CTxB (third panels; overlay in fourth panels). Conjugates were imaged by microscopy on the DeltaVision Elite (60×) and analyzed using ImageJ software. (H) Quantification of conjugates that exhibit CD200R staining within the synapse, as in panel G, expressed as the percentage of total T cell-FBL conjugates. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation from 2 separate experiments for a total of 50 conjugates assessed. (I) pLCK Y394 expression of TCRgag T cells. T cells were transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys (red line), CD200R-CD28cys (blue line), or GFP control (black line) and were left unstimulated (upper left histogram and gray filled in other histograms) or stimulated for 10 minutes with PMA/ionomycin, CD200– FBL, or CD200+ FBL, as indicated. FBL stimulation was performed at an E:T ratio of 10:1; representative of 2 independent experiments.

Although CD200R is expressed on human T cells and signaling via CD200R on T cells inhibits function,20,21 the expression of CD200R on murine T cells is minimal.31 Thus, we questioned if the increased proliferation resulted from the added CD28 costimulation or if the CD200R interaction with the leukemia-expressed CD200 could just reflect enhanced adhesion. To determine the contribution of CD28 signaling to the increased proliferation, we generated a truncated nonsignaling version with only CD200Rec and CD28tm domains (trCD200R, supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site). Transduced TCRgag T cells expressing trCD200R (supplemental Figure 1B) did not exhibit enhanced proliferation to CD200+ FBL (supplemental Figure 1C), indicating a requisite role for CD28 costimulatory signals.

We predicted that the expression of the CD200-targeted IFPs should result in enrichment of IFP+ T cells relative to IFP– T cells after stimulation with CD200+ FBL. Therefore, we assessed the proportion of transduced cells in the total TCRgag population after multiple cycles of stimulation with irradiated CD200– or CD200+ FBL. After 3 cycles of stimulation, the fraction of IFP-expressing TCRgag T cells was increased after stimulation with CD200+ FBL compared with the fraction detected after 3 stimulations with CD200– FBL (supplemental Figure 2). Although several constructs promoted the accumulation of transduced T cells (Figure 2C), the predicted appropriately sized construct that included the dimerizing cysteine motif, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys, produced the greatest relative increase (P < .05), and we thus focused on CD200R-9aas-CD28cys as the lead candidate.

CD28 signaling also promotes effector functions.7 Transduced effector TCRgag T cells were incubated at varying E:T ratios, with a 1:1 mix of CD200+ FBL and nonspecific EL4 control targets for 5 hours, and the lysis percentage was determined by flow cytometry (Figure 2D). TCRgag T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys euthanized CD200+ FBL cells significantly better than control T cells (P < .05).

To determine if T cells transduced with the CD200R-9aas-CD28cys IFP produced increased amounts and diversity of cytokines, functions enhanced by costimulation, we assessed cytokine production by flow cytometry. CD200R IFP+ T cells stimulated with CD200+ FBL produced increased interferon-γ, IL-2, and tumor necrosis factor-α (Figure 2E). Additionally, based on 3 separate experiments (Figure 2F), CD200R IFP+ T cells relative to GFP+ control T cells had a higher proportion of polyfunctional cells in response to CD200+ FBL stimulation (dark gray; mean of 70% vs 42%).

To examine the mechanism of enhanced T-cell function with IFP expression, we compared CD200R IFP location on the T-cell surface via microscopy in T cells transduced with the lead construct (CD200R-9aas-CD28cys), and the ineffective construct that did not promote proliferation (CD200R-CD28cys). Localization of native CD28 to the IS after binding CD80/86 recruits signaling molecules that amplify the TCR signal.7 To assess the movement of the IFPs after stimulation, CTxB was used to stain lipid rafts within the cell membrane (Figure 2G), which are enriched at the IS,32 and to define the site of IS assembly. Antibodies binding CD200 on FBL or CD200R on the T cell were used to visualize these molecules in relation to the IS. CD200R localized at the region of T-cell–target contact in most T cells transduced with the lead construct (CD200R-9aas-CD28cys), but rarely in T cells transduced with the ineffective construct (CD200R-CD28cys; Figure 2H), suggesting that the size of the lead construct allows entry into the IS.

The tyrosine kinase, LCK, is critical for TCR signaling, and recruitment of LCK to the TCR signaling complex phosphorylates immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif sequences in the CD3 complex to initiate the TCR signaling cascade.7 LCK associates with CD28 via a proline motif in the CD28 signaling tail, and CD28 is required for sustained phosphorylation of LCK residue Y394.33 To determine if CD200R-CD28 IFP expression induces or augments this reporter of CD28 signaling, we compared pLCK Y394 in T cells transduced with the GFP control, the lead construct (CD200R-9aas-CD28cys), and the ineffective construct (CD200R-CD28cys). Transduced T cells were unstimulated or stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin, CD200– FBL, or CD200+ FBL for 10 minutes, fixed and stained for ic pLCK Y394, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The 3 populations of T cells phosphorylated LCK Y394 similarly in response to strong stimulation (PMA/ionomycin; Figure 2I). T cells transduced with the GFP control or the larger ectodomain, CD200R-CD28cys, expressed only low-level pLCK Y394 expression in response to CD200– FBL and CD200+ FBL. However, after stimulation with CD200+ FBL CD200R-9aas-CD28cys-transduced T cells exhibited increased phosphorylation of LCK Y394 at 10 minutes associated with CD28 costimulation.

T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys exhibit a similar phenotype in vivo in response to recognition of FBL leukemia

In adoptive T-cell therapy of malignancies, tumors commonly provide limited or no costimulatory signals but rather express ligands for inhibitory receptors. In leukemia, CD200 is a commonly expressed inhibitory ligand associated with poor prognosis.17 Therefore, we examined if expressing the CD200R-9aas-CD28cys IFP, which appeared most effective in vitro, could improve accumulation or alter the phenotype of TCRgag T cells encountering CD200+ FBL in vivo. B6 mice were injected with 4 × 106 CD200+ FBL leukemia i.p. and, after allowing 5 days for the FBL to disseminate, mice received 180 mg/kg cyclophosphamide (Cy) i.p. to reduce tumor burden 6 hours before the transfer of effector T cells. T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys or GFP control appeared phenotypically similar on the day of injection, 5 days after stimulation (supplemental Figure 3). To assess short-term proliferation and accumulation, both populations of T cells were coinjected to determine if the proportion of CD200R IFP-transduced T cells increased relative to the control T cells. Mice were euthanized after 8 days, and we observed a minimal difference in accumulation during this period of homeostatic proliferation (average 1.2-fold enrichment of CD200R IFP+ relative to GFP+, data not shown). To assess possible phenotypic differences acquired by the transferred T cells, separate cohorts of mice were euthanized at early (day 3) and late (day 15) time points to assess effector, memory, and exhaustion markers by flow cytometry. Transduced CD200R-9aas-CD28cys+ TCRgag and control T cells expressed similar surface molecules consistent with an effector T cell phenotype at 3 days posttransfer (Figure 3A) and exhibited a similar phenotype at day 15 (Figure 3B), lacking expression of the exhaustion markers PD-1 or Lag-3 and suggesting that both cell types likely remained functional during this period.

T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cysenhance adoptive immunotherapy of disseminated leukemia. (A-B) CD200R-CD28 IFP-transduced TCRgag T cells were generated as described in Figure 2. B6 mice were injected with 4 × 106 CD200+ FBL cells. Five days later, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys or empty vector control TCRgag T cells were injected into Cy-treated FBL-bearing B6 mice. The expression of surface markers on splenic CD200R-9aas-CD28cys TCRgag T cells (blue lines), control TCRgag T cells (red lines), and endogenous T cells (shaded) was assessed by flow cytometry at days 8 (A) and 15 (B) post–T-cell transfer; representative of 2 independent experiments. (C-D) Survival of mice treated with T-cell immunotherapy in the presence (C) or absence (D) of IL-2 injections. B6 mice were injected with 4 × 106 CD200+ FBL cells. Five days later, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys or empty vector control TCRgag T cells were injected i.p. into Cy-treated FBL-bearing mice at 105 cells/mouse (indicated by arrow). IL-2 was administered every 2 days for a total of 10 days (2 × 104 U/dose) in a cohort of mice. (C) Data from 1 experiment are shown (n = 3-4 mice/group). (D) Pooled data from 3 independent experiments are shown (No therapy [tx], n = 6; Cytoxan [Cy] only, or Cy plus T-cell treated: n = 9-10 mice/group). Statistical analyses are shown: Cy + CD200R-9aas-CD28cys T cells (red) vs Cy + empty vector T cells (blue), *P < .05; Cy + CD200R-9aas-CD28cys T cells (red) vs Cy only (black dashed line), ***P < .001); Cy + empty vector T cells (blue) vs Cy only (blacked dashed line), *P < .05).; and Cy only (blacked dashed line) vs No treatment (tx; black), ****P < .001; log-rank Mantel-Cox test.

T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cysenhance adoptive immunotherapy of disseminated leukemia. (A-B) CD200R-CD28 IFP-transduced TCRgag T cells were generated as described in Figure 2. B6 mice were injected with 4 × 106 CD200+ FBL cells. Five days later, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys or empty vector control TCRgag T cells were injected into Cy-treated FBL-bearing B6 mice. The expression of surface markers on splenic CD200R-9aas-CD28cys TCRgag T cells (blue lines), control TCRgag T cells (red lines), and endogenous T cells (shaded) was assessed by flow cytometry at days 8 (A) and 15 (B) post–T-cell transfer; representative of 2 independent experiments. (C-D) Survival of mice treated with T-cell immunotherapy in the presence (C) or absence (D) of IL-2 injections. B6 mice were injected with 4 × 106 CD200+ FBL cells. Five days later, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys or empty vector control TCRgag T cells were injected i.p. into Cy-treated FBL-bearing mice at 105 cells/mouse (indicated by arrow). IL-2 was administered every 2 days for a total of 10 days (2 × 104 U/dose) in a cohort of mice. (C) Data from 1 experiment are shown (n = 3-4 mice/group). (D) Pooled data from 3 independent experiments are shown (No therapy [tx], n = 6; Cytoxan [Cy] only, or Cy plus T-cell treated: n = 9-10 mice/group). Statistical analyses are shown: Cy + CD200R-9aas-CD28cys T cells (red) vs Cy + empty vector T cells (blue), *P < .05; Cy + CD200R-9aas-CD28cys T cells (red) vs Cy only (black dashed line), ***P < .001); Cy + empty vector T cells (blue) vs Cy only (blacked dashed line), *P < .05).; and Cy only (blacked dashed line) vs No treatment (tx; black), ****P < .001; log-rank Mantel-Cox test.

CD200R-9aas-CD28cys+ T cells are more effective in adoptive therapy of disseminated leukemia

We next sought to determine if the costimulation provided to cells expressing CD200R-9aas-CD28cys IFPs resulted in enhanced therapeutic T-cell activity in the FBL preclinical mouse model of disseminated leukemia, which requires a T-cell response lasting >25 days to achieve leukemia eradication.34 Mice were injected with a lethal dose (4 × 106) of CD200+ FBL leukemia; 5 days later, cohorts of mice were treated with Cy and received 105 T cells 6 hours later to allow for metabolism of the drug.34 The efficacy of therapy with T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys was compared with T cells expressing an empty vector control (Figure 3C-D). We initially tested this approach with a small cohort of mice that also received IL-2 for 10 days after T-cell transfer to enhance and sustain T-cell activity29 (Figure 3C). With IL-2 injections, immunotherapy using the control T cells cured 67% of mice and CD200R-9aas-CD28cys+ T cells cured 100% of mice, which suggested enhanced activity but did not achieve statistical significance. Therapy with IL-2 can result in toxicity and induction of T regulatory cells that constitutively express the high affinity IL-2 receptor, resulting in an inhibited immune response.35 Because CD28 signaling can increase cell-intrinsic IL-2 secretion by increasing and stabilizing the production of IL-2 messenger RNA, resulting in a 50-fold increase in production,36 we tested our CD200R IFP T-cell immunotherapy in the absence of IL-2 injections to determine if the CD28 signal from the IFP replaced the dependence on exogenous IL-2. A total of 40% of mice treated with T cells transduced with the control vector survived 100 days post–tumor transfer (Figure 3D, blue line, P < .05 vs Cy alone). By contrast, mice treated with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys T cells exhibited additionally enhanced survival in each of the 3 independent experiments and yielded an overall survival rate of 89% (CD200R-9aas-CD28cys T cells vs empty vector control T cells, *P < .05 and vs Cy only, ***P < .001). Thus, an IFP with CD28 providing a costimulatory signal not only enhances T-cell immunotherapy of progressive leukemia, but largely replaces the requirement for the administration of IL-2.

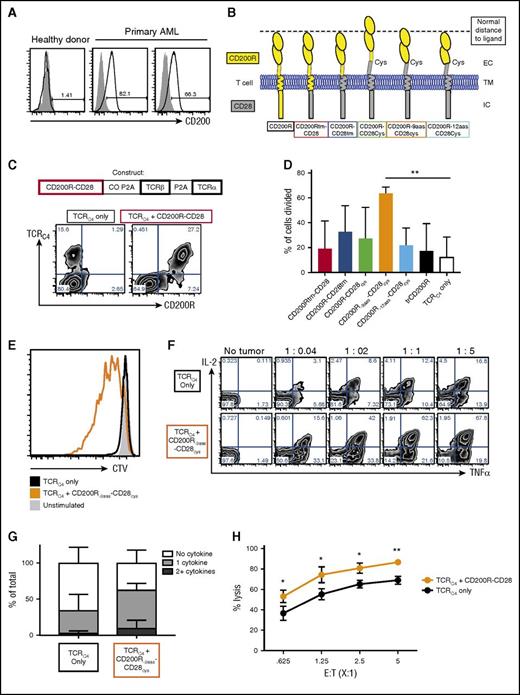

A human CD200-CD28 IFP improves the function of TCR-transduced primary CD8 T cells

Leukemic specimens were obtained from patients who had relapsed after an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. The expression of CD200 on the CD45dimCD34+ population was compared with cells obtained from a mobilized leukapheresis from a healthy donor. Although CD200 expression was not detected on normal CD34+ cells, CD200 was expressed by a large fraction of AML blasts from each patient tested (range, 66%-82%+; Figure 4A), consistent with previous reports.17,37

Coexpression of CD200R-CD28 enhances function in WT1-specific TCR-transduced human primary T cells. (A) Expression of CD200 on CD45dimCD34+ cells (black lines) from a healthy donor leukapheresis sample (left panel) or leukemic blasts from 2 separate donors (center and right panels) in relation to matched FMO control (gray shaded). (B) Schematic representation of CD200R-CD28 constructs. CD200Rtm-CD28 contains CD200R ec and tm domains and a CD28 ic signaling domain. CD200R-CD28tm contains the ec domain of CD200R and the tm and ic domains of CD28. The remaining 3 constructs also incorporate 12 aas of the ec domain of CD28 to the tm-proximal cysteine to promote multimerization and enhance CD28 signaling. To account for the extra CD28 residues, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys has a truncated portion of CD200R that removes the 9-aa membrane-proximal stem region, and CD200R-12aas-CD28cys has a truncated portion of CD200R that removes 12 membrane-proximal residues that include additional amino acids beyond the stem region. The first, second, and fifth constructs are predicted to approximate the spatial distance between the T cell and an APC, as indicated by the dashed line. (C-H) CD8+ T cells were enriched by magnetic beads from PBMCs harvested from healthy HLA-A2+ donors. CD8+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads and transduced with lentiviral supernatant for 2 days. Transduced T cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and restimulated by rapid expansion protocol every 10 to 14 days in the presence of IL-2. (C) Diagram of construct combining IFP, TCRα, and TCRβ chains. The IFP constructs were inserted into single lentiviral vectors with the β and α chains of the HLA-A2–restricted WT1126-specific TCRC4. The first P2A sequence was codon optimized (CO P2A) to prevent genetic recombination with the second P2A sequence (P2A). Flow cytometry plots show expression of TCRC4 only (left plot) or TCRC4 + CD200R-CD28 (right plot) in primary human T cells as detected by anti-CD200R antibody and WT1126 HLA-A2 tetramer binding. (D) Proliferation of T cells as detected by dilution of CTV. Primary human T cells transduced with TCRC4 or TCRC4 and CD200R IFP were stained with CTV and stimulated with WT1126-pulsed T2 cells at an E:T ratio of 25:1 in the absence of IL-2 for 6 days. The percentage of cells that diluted CTV (proliferated) was determined by FlowJo proliferation analysis. Cumulative of 3 independent T-cell donors (**P < .01). (E) Representative histogram of CTV dilution in unstimulated (gray filled), TCRC4-transduced (black line), or TCRC4- and CD200R-9aas-CD28cys-transduced (orange line) T cells. (F) Intracellular cytokine production of CD8+ T cells. Primary human T cells transduced with TCRC4 only (upper panels) or TCRC4 and CD200R-9aas-CD28cys-transduced (lower panels) were unstimulated or stimulated with WT1126-pulsed T2 cells for 6 hours in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). T cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for ic cytokines and assessed by flow cytometry. (G) Summary of cytokine production in panel F (E:T ratio, 1:1). Data are presented as no cytokine (white), 1 cytokine (light gray), or 2+ cytokine (dark gray) production; cumulative results of 3 independent T-cell donors. (H) Cytotoxicity assay. Primary AML blasts were cocultured with primary human T cells transduced with TCRC4 alone (black symbols) or TCRC4 and the CD200R-9aas-CD28cys IFP (orange symbols) for 24 hours. Remaining viable blasts were quantified by flow cytometry and the percentage of lysis was determined after normalization with the tumor-only control well (assayed in triplicate; *P < .05, **P < .01).

Coexpression of CD200R-CD28 enhances function in WT1-specific TCR-transduced human primary T cells. (A) Expression of CD200 on CD45dimCD34+ cells (black lines) from a healthy donor leukapheresis sample (left panel) or leukemic blasts from 2 separate donors (center and right panels) in relation to matched FMO control (gray shaded). (B) Schematic representation of CD200R-CD28 constructs. CD200Rtm-CD28 contains CD200R ec and tm domains and a CD28 ic signaling domain. CD200R-CD28tm contains the ec domain of CD200R and the tm and ic domains of CD28. The remaining 3 constructs also incorporate 12 aas of the ec domain of CD28 to the tm-proximal cysteine to promote multimerization and enhance CD28 signaling. To account for the extra CD28 residues, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys has a truncated portion of CD200R that removes the 9-aa membrane-proximal stem region, and CD200R-12aas-CD28cys has a truncated portion of CD200R that removes 12 membrane-proximal residues that include additional amino acids beyond the stem region. The first, second, and fifth constructs are predicted to approximate the spatial distance between the T cell and an APC, as indicated by the dashed line. (C-H) CD8+ T cells were enriched by magnetic beads from PBMCs harvested from healthy HLA-A2+ donors. CD8+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads and transduced with lentiviral supernatant for 2 days. Transduced T cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and restimulated by rapid expansion protocol every 10 to 14 days in the presence of IL-2. (C) Diagram of construct combining IFP, TCRα, and TCRβ chains. The IFP constructs were inserted into single lentiviral vectors with the β and α chains of the HLA-A2–restricted WT1126-specific TCRC4. The first P2A sequence was codon optimized (CO P2A) to prevent genetic recombination with the second P2A sequence (P2A). Flow cytometry plots show expression of TCRC4 only (left plot) or TCRC4 + CD200R-CD28 (right plot) in primary human T cells as detected by anti-CD200R antibody and WT1126 HLA-A2 tetramer binding. (D) Proliferation of T cells as detected by dilution of CTV. Primary human T cells transduced with TCRC4 or TCRC4 and CD200R IFP were stained with CTV and stimulated with WT1126-pulsed T2 cells at an E:T ratio of 25:1 in the absence of IL-2 for 6 days. The percentage of cells that diluted CTV (proliferated) was determined by FlowJo proliferation analysis. Cumulative of 3 independent T-cell donors (**P < .01). (E) Representative histogram of CTV dilution in unstimulated (gray filled), TCRC4-transduced (black line), or TCRC4- and CD200R-9aas-CD28cys-transduced (orange line) T cells. (F) Intracellular cytokine production of CD8+ T cells. Primary human T cells transduced with TCRC4 only (upper panels) or TCRC4 and CD200R-9aas-CD28cys-transduced (lower panels) were unstimulated or stimulated with WT1126-pulsed T2 cells for 6 hours in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). T cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for ic cytokines and assessed by flow cytometry. (G) Summary of cytokine production in panel F (E:T ratio, 1:1). Data are presented as no cytokine (white), 1 cytokine (light gray), or 2+ cytokine (dark gray) production; cumulative results of 3 independent T-cell donors. (H) Cytotoxicity assay. Primary AML blasts were cocultured with primary human T cells transduced with TCRC4 alone (black symbols) or TCRC4 and the CD200R-9aas-CD28cys IFP (orange symbols) for 24 hours. Remaining viable blasts were quantified by flow cytometry and the percentage of lysis was determined after normalization with the tumor-only control well (assayed in triplicate; *P < .05, **P < .01).

Based on insights from the murine data, we generated a panel of constructs that differed in the tm domain, incorporated the CD28 cysteine (12 ec membrane–proximal aas), and/or truncated the CD200R ectodomain to accommodate the ec CD28 residues (Figure 4B). Because the stem region of CD200R is predicted to be 9 aas,12 we included a construct that deleted 9 residues from CD200R (CD200R-9aas-CD28cys), because the removal of additional amino acids beyond the stem region (CD200R-12aas-CD28cys) may interfere with protein structure or ligand binding. However, we also tested CD200R-12aas-CD28cys to approximate the additional amino acids.

The constructs were inserted into single lentiviral vectors with the β and α chains of the HLA-A2–restricted WT1126-specific TCRC4,38 which we are using in a clinical trial for T-cell immunotherapy of AML (www.clinicaltrials.gov, #NCT01640301), by linking each of the genes with P2A elements (Figure 4C). The first P2A sequence was codon optimized to prevent genetic recombination with the second P2A sequence. Human primary T cells transduced to express TCRC4 and the CD200R-CD28 fusion proteins exhibited a high level of CD200R expression and equivalent levels of TCRC4 expression as T cells transduced with TCRC4 alone (Figure 4C).

To determine if the CD200R-CD28 IFP improved proliferation, transduced T cells were stimulated with WT1126-pulsed T2 lymphoblastoid cells that naturally express endogenous CD200 (compared with the CD200– K562 cell line,22 supplemental Figure 4). At a low E:T ratio (25:1), T cells transduced with TCRC4 exhibited minimal proliferation, however, several IFPs improved proliferation (Figure 4D-E). A decoy CD200R (ec + tm only) slightly improved proliferation, but this did not reach statistical significance (black bar, Figure 4D). When repeated with 2 additional donors, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys consistently improved proliferation (average of 64% vs 12% [TCRC4 only], Figure 4D, **P < .01). This IFP also improved cytokine production, increasing sensitivity to stimulation (Figure 4F) and polyfunctionality (Figure 4G). To assess cytotoxic function, we coincubated T cells with primary AML cells for 24 hours and quantified the remaining viable blasts by flow cytometry,39 and the CD200R-CD28 IFP+ T cells exhibited improved lytic activity (Figure 4H, *P < .05, **P < .01).

Discussion

Adoptive immunotherapy of cancer with engineered T cells is an evolving strategy that has shown dramatic activity in many malignancies.1,30,40,41 However, upregulation of inhibitory receptor ligands by tumor cells can prevent T-cell activation and block immune-mediated tumor eradication. Consequently, the use of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to block checkpoint signaling from the associated receptor has been pursued in immunotherapy with remarkable results in some cancers,42-44 but such systemic blockade with mAbs globally targets the immune system and is often associated with severe autoimmune toxicities.45,46 Our study focused on optimizing an IFP to target the inhibitory molecule, CD200, which is frequently upregulated on cancer cells, particularly AML and leukemia stem cells,18,19,47 and known to suppress human T-cell immune responses.20 Our results show that genetic engineering of tumor-specific T cells with CD200R-CD28 IFP can efficiently convert an inhibitory signal delivered by leukemic cells to a costimulatory one in a cell-intrinsic fashion, thus obviating the requirement to globally block this inhibitory receptor with the associated risk of promoting activation of endogenous autoreactive T cells.

We selected CD200 for targeting in part because the natural CD200/200R interaction is projected to be sized appropriately to fit within the IS,12 and we anticipated that entry into the IS would be required for effective CD28 costimulation. The panel of constructs designed varied the fusion regions of CD200R and the CD28 signaling domain to test several factors: the importance of the size of the ectodomain, the contribution of a cysteine bond in the CD28 ectodomain that promotes dimerization, which is known to facilitate CD28 signaling,28 and the contribution of a glycosylation site in the CD200R ectodomain to a functional conformation. We found, in both murine and human studies, that the receptor that retained a size predicted to permit entry to the IS and that preserved a dimerizing motif was most effective, and we predict that these concepts will inform the design of IFPs using the CD28 costimulatory signal and targeting other ligands.

The addition of costimulatory signals to engineered T cells is attractive for TCR gene therapy. Costimulatory signals lower the activation threshold, allowing higher sensitivity to low-abundance antigens,48 and the absence of costimulation on antigen recognition can induce a state of nonresponsiveness, termed anergy.36 Inclusion of a CD28 or alternative costimulatory domain is a requisite for the effective stimulation of T cells transduced with a CAR with an antibody ectodomain for antigen recognition and a CD3ζ domain for T-cell activation. However, ligation of CD3ζ and/or costimulatory signaling domains directly to the ic tail of TCR chains reduced the sensitivity of transduced T cells to peptide-major histocompatibility complex stimulation compared with introduced unmodified TCR Vα and Vβ chains (data not shown and Stone et al49 ). This suggests that direct manipulation of the tails of TCR chains interferes with the assembly/function of the CD3 signaling complex, blunting activation. By contrast, IFPs can improve sensitivity while leaving the TCR unmanipulated.

The approach described in this article has several advantages compared with related strategies to bolster T-cell immunotherapy. Inhibitory receptors can be genetically deleted from engineered T cells, but this simply removes a brake, whereas IFPs can replace the brake with an accelerator by the addition of costimulatory signaling domains. However, we do not yet know if achieving high expression of the IFP serves as a dominant negative that prevents the negative signal, or if concurrent deletion of the inhibitory receptor, as might be achieved with short hairpin RNA or gene editing,50,51 will additionally enhance therapy. As noted above, in contrast with mAb checkpoint blockade therapy, genetic manipulation of transferred T cells avoids reducing the threshold of activation of endogenous T cells for which TCR specificity is not known and could be self reactive. Additionally, IFPs may provide a safer method for targeting tumor proteins that exhibit upregulated, but not exclusive, expression on tumor cells, because the normal cells will generally not express the inhibitory ligand.

The activity observed with a CD200-targeting IFP in leukemia suggests a potential to provide benefit for treating other tumors. In addition to AML, increased CD200 expression has been reported for other hematologic malignancies and solid tumors, such as breast, colon, ovarian, and prostate cancers,13-15 and CD200 may be a targetable inhibitory ligand in these tumors. It is feasible to express IFPs with different signaling domains in the same T cell to both target multiple inhibitory molecules and to provide additional activation signals. Studies in AML patients have revealed linked expression of CD200 with another well-documented inhibitory receptor ligand, PD-L1,37 and targeting both inhibitory ligands could have an additive or synergistic effect. Our work demonstrates that using structure-based design of IFPs for targeting immunosuppressive molecules can generate costimulatory signals with enhanced activity for use in T-cell immunotherapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cyr de Imus, Julio Vazquez Lopez, Elizabeth Jensen, Kumiko Tsubota, Hieu Nguyen, Natalie Duerkopp, and the Fred Hutch Cancer Research Center Flow Cytometry Core for technical support. The authors also thank Deborah Banker for assistance with manuscript preparation and Rachel Perret for helpful conversations.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants CA018029 and CA033084 (P.D.G.), the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (S.K.O.), and Juno Therapeutics (P.D.G.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: S.K.O., A.W.D., N.M.G., F.W., and X.T. performed the experiments; S.K.O., A.W.D., N.M.G., and F.W. analyzed the data; T.M.S. generated reagents; S.K.O., A.G.C., and P.D.G. designed the study; and S.K.O. and P.D.G. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.D.G. has an equity interest in Juno Therapeutics, Inc., and receives a consulting payment from Juno Therapeutics, Inc. P.D.G, S.K.O., and T.M.S are named as inventors on 1 or more patent and/or patent application related to this work. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Philip D. Greenberg, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave N, Seattle, WA 98109; e-mail: pgreen@uw.edu.

![Figure 2. CD200R-CD28 constructs promote proliferation, accumulation, and effector function of transduced T cells stimulated by CD200+ tumor target cells in vitro. Splenocytes from naive TCRgag mice were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL), anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL), and recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2, 100 U/mL) and transduced with retroviral supernatant for 2 days. Cells were restimulated every 7 days with irradiated FBL and splenocytes and cultured with rhIL-2 (50 U/mL) for ≤3 stimulations. T cells were used for assays 5 to 7 days after the last stimulation. (A) Proliferation of CD200R-CD28 (red lines) and GFP empty vector control (blue lines) TCRgag T cells as measured by CTV dilution after stimulation with CD200– FBL (upper panels) or CD200+ FBL (lower panels) at a low E:T ratio of 25:1 for 3 days. (B) Cumulative proliferation of cells depicted in panel A. Proliferation was normalized across experiments by assessing the proportion of divided CD200R-CD28+ T cells relative to empty vector–transduced T cells (% dividedCD200R+/% dividedCD200R– [n = 3]). (C) Enrichment of transduced TCRgag T cells in a mixed population including nontransduced TCRgag T cells after 3 weekly cycles of stimulation with irradiated CD200+ FBL and splenocytes (n = 4-5/group). **P < .01 (Student t test). (D) Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester cytotoxicity assay. TCRgag T cells were transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys (red bars) or mock-transduced cells (black bars). Effector TCRgag T cells were incubated at the indicated effector to target ratio with a 1:1 mix of CD200+ FBL and nonspecific EL4 control targets for 4 hours. The relative frequency of FBL vs control tumor cells was determined by flow cytometry, and the percentage of specific lysis was determined by the frequency of FBL cells after T-cell culture relative to FBL incubated without T cells; cumulative of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 (Student t test). (E) Cytokine production of TCRgag T cells transduced with GFP control (black lines) or CD200R IFP (red lines) relative to unstimulated T cells (gray filled) after coculture at a 1:1 ratio with CD200– (upper histograms) or CD200+ (lower histograms) FBL for 4 hours in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Cells were fixed, permeabilized, stained for ic cytokines, and assessed by flow cytometry. (F) Summary of panel E. Stacked bar charts of cytokine production in TCRgag T cells in response to CD200– (left) or CD200+ (right) FBL stimulation at a 1:1 ratio. Data are presented as no cytokine (white), 1 cytokine (light gray), or 2+ cytokine (dark gray) production; cumulative results of 3 independent experiments. (G) Visualization of CD200R localization within T cell-FBL conjugates. TCRgag in vitro expanded effector T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys (upper panels) or CD200R-CD28cys (lower panels) were cocultured with CD200+ FBL at an E:T ratio of 10:1 at 37°C for 20 minutes to allow conjugate formation. Conjugates were loaded on a μ-Slide VI 0.4 chamber (Ibidi) for an additional 15 minutes. Cells were fixed and stained for CD200R (first panels), CD200 (second panels), and lipid rafts by CTxB (third panels; overlay in fourth panels). Conjugates were imaged by microscopy on the DeltaVision Elite (60×) and analyzed using ImageJ software. (H) Quantification of conjugates that exhibit CD200R staining within the synapse, as in panel G, expressed as the percentage of total T cell-FBL conjugates. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation from 2 separate experiments for a total of 50 conjugates assessed. (I) pLCK Y394 expression of TCRgag T cells. T cells were transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys (red line), CD200R-CD28cys (blue line), or GFP control (black line) and were left unstimulated (upper left histogram and gray filled in other histograms) or stimulated for 10 minutes with PMA/ionomycin, CD200– FBL, or CD200+ FBL, as indicated. FBL stimulation was performed at an E:T ratio of 10:1; representative of 2 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/22/10.1182_blood-2017-04-777052/4/m_blood777052f2.jpeg?Expires=1765898897&Signature=tWUkwBOSrW5G6YUhOMSd0aPOFEykq9iuxdQzqbr8sPw2Xi39OssOt4lJOtaKRb71RjDIKjmQc7s~fpIUlwKN0LulY2eklAC4W7xkW9HUa0Vaxgr-Aox1~dVOgVndyPx3oEBLpsgzNQlvdG3uJF5~fgibmrZW3GFFPzFjM1y7EKooyAT5F4VLDFGCkBAghcNY9ZdEpM2RjbwlZulZ4f6pAvBSfoaRteNtfMOp2cFisl162SRiKKzBYM76-N2Ziz5gR6A4q7WbqIKBjmLNgDQYtkfYQShxBDN42EijIpDCMmqsVX1MiifpLRZe~F00Kx8q22zgia4gSzhqzXiaboqBxw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. T cells transduced with CD200R-9aas-CD28cys enhance adoptive immunotherapy of disseminated leukemia. (A-B) CD200R-CD28 IFP-transduced TCRgag T cells were generated as described in Figure 2. B6 mice were injected with 4 × 106 CD200+ FBL cells. Five days later, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys or empty vector control TCRgag T cells were injected into Cy-treated FBL-bearing B6 mice. The expression of surface markers on splenic CD200R-9aas-CD28cys TCRgag T cells (blue lines), control TCRgag T cells (red lines), and endogenous T cells (shaded) was assessed by flow cytometry at days 8 (A) and 15 (B) post–T-cell transfer; representative of 2 independent experiments. (C-D) Survival of mice treated with T-cell immunotherapy in the presence (C) or absence (D) of IL-2 injections. B6 mice were injected with 4 × 106 CD200+ FBL cells. Five days later, CD200R-9aas-CD28cys or empty vector control TCRgag T cells were injected i.p. into Cy-treated FBL-bearing mice at 105 cells/mouse (indicated by arrow). IL-2 was administered every 2 days for a total of 10 days (2 × 104 U/dose) in a cohort of mice. (C) Data from 1 experiment are shown (n = 3-4 mice/group). (D) Pooled data from 3 independent experiments are shown (No therapy [tx], n = 6; Cytoxan [Cy] only, or Cy plus T-cell treated: n = 9-10 mice/group). Statistical analyses are shown: Cy + CD200R-9aas-CD28cys T cells (red) vs Cy + empty vector T cells (blue), *P < .05; Cy + CD200R-9aas-CD28cys T cells (red) vs Cy only (black dashed line), ***P < .001); Cy + empty vector T cells (blue) vs Cy only (blacked dashed line), *P < .05).; and Cy only (blacked dashed line) vs No treatment (tx; black), ****P < .001; log-rank Mantel-Cox test.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/22/10.1182_blood-2017-04-777052/4/m_blood777052f3.jpeg?Expires=1765898898&Signature=Y~ty8TqTcadPQRZp5vJHII71UxTmr5UHYfo2uqtnXHoD47mjE9bd2~WRiBt2MzfaYU1mwlikTspsQeYEiHSYfTjDlMQIrf1Jz39I5iBFZ8rL1NheoHITF-6Ow-FN7vQA828dIfg90ywXcuDr4u58wKOIo33w1KX8QP0ST6FktyaGJ~GPcc~poyCMxT1YSLLEirJ6xuFgjicn5DDu1XUSwyb6W1CEQRbEG6nCg1DmXm5rqtb9KiFxqamcmJKmi61UdIkFnRaMcfs6FmUGRvqfyXGVYNp~JY17blyGpLlLDQk9Q0PmwNzBuwqEK6jkEEUIALYSLLdfeGqZ04zM2BWerQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal