Key Points

TCR SE is a clinically feasible approach to rapidly produce highly performing and specific tumor reactive T cells.

NY-ESO-1 TCR SE T cells kill multiple myeloma in the absence of off-target reactivity including alloreactivity.

Abstract

Transfer of T-cell receptors (TCRs) specific for tumor-associated antigens is a promising approach for cancer immunotherapy. We developed the TCR gene editing technology that is based on the knockout of the endogenous TCR α and β genes, followed by the introduction of tumor-specific TCR genes, and that proved safer and more effective than conventional TCR gene transfer. Although successful, complete editing requires extensive cell manipulation and 4 transduction procedures. Here we propose a novel and clinically feasible TCR “single editing” (SE) approach, based on the disruption of the endogenous TCR α chain only, followed by the transfer of genes encoding for a tumor-specific TCR. We validated SE with the clinical grade HLA-A2 restricted NY-ESO-1157-165–specific TCR. SE allowed the rapid production of high numbers of tumor-specific T cells, with optimal TCR expression and preferential stem memory and central memory phenotype. Similarly to unedited T cells redirected by TCR gene transfer (TCR transferred [TR]), SE T cells efficiently killed NY-ESO-1pos targets; however, although TR cells proved highly alloreactive, SE cells showed a favorable safety profile. Accordingly, when infused in NSG mice previously engrafted with myeloma, SE cells mediated tumor rejection without inducing xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease, thus resulting in significantly higher survival than that observed in mice treated with TR cells. Overall, single TCR gene editing represents a clinically feasible approach that is able to increase the safety and efficacy of cancer adoptive immunotherapy.

Introduction

Although the infusion of ex vivo expanded tumor-specific T cells to melanoma patients has documented the efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy,1 the exploitation of this strategy to other forms of cancer remains limited by the low frequency of tumor-reactive high-avidity T cells. Indeed, tumor antigens are often overexpressed, unmodified self-antigens, subject to tolerance.2 Although neoantigens derived from oncogenic mutations can elicit T-cell responses,3 these are rarely observed in tumors with a low mutational load, such as most hematological malignancies.4 These limitations can be overcome by engineering high-avidity tumor-reactive T-cell receptors (TCRs), obtained from rare tumor-specific T cells, into mature lymphocytes. This is a flexible strategy, theoretically applicable in the autologous context and in the HLA-matched allogeneic setting, and that could be potentially exploited to generate third-party tumor-specificlymphocytes, in an “off-the-shelf” approach. In initial clinical trials of TCR gene transfer objective responses were observed at lower frequencies than with naturally occurring tumor-specific effectors.5 Indeed, TCR gene transfer suffers of some limitations intrinsic to the TCR biology that affect safety and efficacy of the cellular products. The tumor-specific TCR competes with the endogenous ones for binding to CD3, leading to mutual TCR dilution and reduced T-cell avidity and antitumor efficacy. Furthermore, because TCRs are heterodimers, the α and β chains of the endogenous TCR might mispair with the respective α and β chains of the transgenic TCR to produce new hybrid receptors, with unpredictable and potentially harmful specificities.6 These limitations represent major concerns both in the autologous and in the allogeneic settings, in which TCR misparing might increase the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) associated with the alloreactive T-cell repertoire.7,8

Several strategies have been developed to increase TCR affinity and foster correct TCR pairing.9 We demonstrated that combining zinc finger nuclease (ZFN)–driven disruption of the endogenous TCR α and β chain genes with lentiviral delivery of a tumor-specific TCR results in the successful and complete editing (CE) of T-cell specificity10 displaying high avidity in the absence of TCR mispairing. However, the CE approach involves 4 distinct steps of genetic manipulation and sorting, requires 40 days of culture, and leads to small numbers of tumor-redirected T cells, which need further expansion. The extensive manipulation might reduce the overall fitness of gene-modified cells, and the procedure is limited by high costs and regulatory hurdles. We designed a simplified TCR gene editing protocol, based on the disruption of only the TCR α chain followed by the simultaneous introduction of the tumor-specific TCR chain genes. Through such a single editing (SE) procedure, we can obtain high numbers of SE cells in 2 weeks. Torikai et al reported that the genetic disruption of 1 TCR chain gene, followed by the genetic transfer of a chimeric antigen receptor, allows the generation of tumor-specific T cells devoid of the original TCR repertoire,11 and this approach has been recently successfully tested in 2 patients with relapsed refractory CD19pos acute lymphoblastic leukemia as a bridge to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.12 In contrast to this strategy, the TCR SE approach could theoretically result in some level of mispairing between the tumor-specific TCR chains and the remaining endogenous one. Here we show that the associated risk of off-target reactivity is counterbalanced by the advantage obtained by the elimination of the TCR endogenous repertoire. We took advantage of an HLA-A2–restricted, NY-ESO-1157-165–specific TCR to redirect cells toward the NY-ESO-1 cancer testis antigen,13-16 expressed by a high proportion of tumors, including multiple myeloma (MM)17-19 and showed that SE lymphocytes are superior to unedited T cells redirected by TCR gene transfer.

Methods

Gene transfer tools

Pairs of previously described10 ZFNs targeting either the TCR α constant (TRAC) gene or the TRBC gene were transiently expressed on primary T cells by Ad5/F35 adenoviral vector (AdV)10,20,21 or messenger RNA (mRNA) electroporation (see supplemental Data, available on the Blood Web site). The HLA-A2–restricted, NY-ESO-1157-165–specific TCR genes were obtained through the Adoptive engineered T cell Trials to Achieve Cancer Killing (ATTACK) consortium22 and cloned into self-inactivating lentiviral vectors (LVs) under the PGK promoter. For the CE procedure, NY-ESO-1–specific TCR α and β chains were cloned into separate vectors (NY-ESO-1 TCRα LV and NY-ESO-1 TCRβ LV), whereas for the SE protocol both chains were cloned into a single vector and linked with a PTV1.2A self-cleavage peptide sequence and a furin cleavage recognition site (NY-ESO-1 TCR LV). In selected experiments, an LV encoding both WT1-specific α and β TCR chains under a bidirectional promoter10 was used. LVs were packaged by an integrase-competent third-generation construct and pseudotyped by the vescicular stomatitis virus (VSV) envelope.23

Culture conditions and gene transfer protocols

We cultured the T2, U266, and MM.1S cell lines in RPMI 1640 supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). MR245, MSR3-LA2, and SK23 cell lines were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, and 10% FBS. We obtained human T lymphocytes from healthy donors, upon informed consent. Lymphocytes were activated by magnetic beads conjugated to antibodies to CD3 and CD28 (ClinExVivo baCD3/CD28) and cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, 10% FBS, and 5 ng/mL of interleukin-7 (IL-7) and IL-15 as described.10 Medium was replaced every 3 to 4 days. The first gene transfer step was performed 48 hours after activation. For TCR SE, ZFN-AdV-transduced or mRNA-electroporated lymphocytes, sorted as CD3neg cells, were subsequently transduced with the NY-ESO-1-TCR LV. TCR CE was performed as previously described10 (Figure 1A). Cells were expanded as described.24 When indicated, we sorted Vβ13.1pos, Vβ21.3pos, CD3neg, CD3pos, and NY-ESO-1 dextramerpos cells using selection columns and anti-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti-CD3, or anti-phycoerythrin (PE) MACS MicroBeads, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

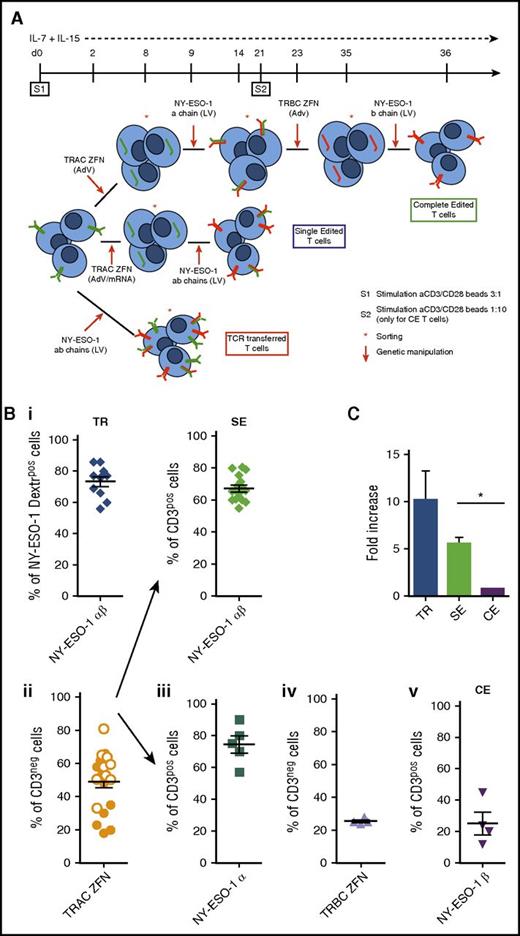

TCR gene transfer, TCR SE, and TCR CE redirect T cells toward NY-ESO-1. (A) Illustration summarizing procedure and timeline for the production of CE (upper panel), SE (middle panel), and TCR transferred (TR; lower panel) NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells. CE: At day 0 T cells harvested from healthy donors are stimulated with cell-sized beads coated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (cell/bead ratio = 3:1) and kept in culture with low doses of IL-7 and IL-15 (5 ng/mL each). Two days later, the gene encoding for the constant region of the α chain (TRAC) is permanently disrupted by ZFNs delivered through AdVs. Gene modified cells are identified as CD3neg, sorted by magnetic selection at day 8, and subsequently transduced with an LV to express the NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR α chain. T cells expressing the tumor-specific TCR α chain reexpress CD3 on cell surface and can thus be selected and restimulated with a cell/bead ratio of 1:10 (S2). The subsequent steps of TRBC ZFN delivery (to disrupt the β chain constant region gene of the endogenous TCRs), CD3neg cell sorting, and NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR-specific β chain transduction occur at days 23, 35, and 36, respectively. The final T-cell product, after 5 to 6 weeks of cell manipulation, is a population of CE T cells fully and permanently redirected toward the NY-ESO-1 antigen. SE: After stimulation (S1), superimposable to that of the CE protocol, the TRAC gene is permanently disrupted by ZFNs delivered through AdVs or mRNA electroporation. CD3neg cells are sorted and at day 9, transduced with an LV encoding the NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR α and β chain genes. SE CD3pos T cells, obtained in 2 weeks within S1, although still bearing the endogenous β TCR chains, are completely devoid of their endogenous TCR repertoire. TR: Two days after S1, activated T cells are transduced with an LV encoding for the NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR α and β chains. Transduced cells are subsequently sorted either by Vβ13.1 or by NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer. (B) The efficiency of each manipulation step used in the CE, SE, and TR protocols was determined by flow cytometry on 4 healthy donors as follows: (i) transduction efficiency of the LV encoding for the NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR (NY-ESO-1 α and β chains) for transferred (upper left panel) and SE (upper right panel) cells was determined by the quantification of NY-ESO-1 dextramerpos and CD3pos cells respectively; (ii) TRAC ZFN activity by AdV (orange dots) or mRNA electroporation (white dots) was measured by quantification of CD3neg cells (lower left panel); (iii) transduction efficiency of LV encoding for the single NY-ESO-1 TCR α chain was determined by quantification of CD3pos cells; (iv) TRBC ZFN adenoviral activity was measured by the quantification of CD3neg cells; and (v) transduction efficiency of LV encoding for the single NY-ESO-1 β chain was assessed by quantifying CD3pos cells (lower right panels). (C) Fold increase in the number of NY-ESO-1–redirected TR, SE, and CE T cells at the end of the manipulation procedure. Means and standard error of the mean (SEM) shown. *P = .013.

TCR gene transfer, TCR SE, and TCR CE redirect T cells toward NY-ESO-1. (A) Illustration summarizing procedure and timeline for the production of CE (upper panel), SE (middle panel), and TCR transferred (TR; lower panel) NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells. CE: At day 0 T cells harvested from healthy donors are stimulated with cell-sized beads coated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (cell/bead ratio = 3:1) and kept in culture with low doses of IL-7 and IL-15 (5 ng/mL each). Two days later, the gene encoding for the constant region of the α chain (TRAC) is permanently disrupted by ZFNs delivered through AdVs. Gene modified cells are identified as CD3neg, sorted by magnetic selection at day 8, and subsequently transduced with an LV to express the NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR α chain. T cells expressing the tumor-specific TCR α chain reexpress CD3 on cell surface and can thus be selected and restimulated with a cell/bead ratio of 1:10 (S2). The subsequent steps of TRBC ZFN delivery (to disrupt the β chain constant region gene of the endogenous TCRs), CD3neg cell sorting, and NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR-specific β chain transduction occur at days 23, 35, and 36, respectively. The final T-cell product, after 5 to 6 weeks of cell manipulation, is a population of CE T cells fully and permanently redirected toward the NY-ESO-1 antigen. SE: After stimulation (S1), superimposable to that of the CE protocol, the TRAC gene is permanently disrupted by ZFNs delivered through AdVs or mRNA electroporation. CD3neg cells are sorted and at day 9, transduced with an LV encoding the NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR α and β chain genes. SE CD3pos T cells, obtained in 2 weeks within S1, although still bearing the endogenous β TCR chains, are completely devoid of their endogenous TCR repertoire. TR: Two days after S1, activated T cells are transduced with an LV encoding for the NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR α and β chains. Transduced cells are subsequently sorted either by Vβ13.1 or by NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer. (B) The efficiency of each manipulation step used in the CE, SE, and TR protocols was determined by flow cytometry on 4 healthy donors as follows: (i) transduction efficiency of the LV encoding for the NY-ESO-1157-165 TCR (NY-ESO-1 α and β chains) for transferred (upper left panel) and SE (upper right panel) cells was determined by the quantification of NY-ESO-1 dextramerpos and CD3pos cells respectively; (ii) TRAC ZFN activity by AdV (orange dots) or mRNA electroporation (white dots) was measured by quantification of CD3neg cells (lower left panel); (iii) transduction efficiency of LV encoding for the single NY-ESO-1 TCR α chain was determined by quantification of CD3pos cells; (iv) TRBC ZFN adenoviral activity was measured by the quantification of CD3neg cells; and (v) transduction efficiency of LV encoding for the single NY-ESO-1 β chain was assessed by quantifying CD3pos cells (lower right panels). (C) Fold increase in the number of NY-ESO-1–redirected TR, SE, and CE T cells at the end of the manipulation procedure. Means and standard error of the mean (SEM) shown. *P = .013.

Flow cytometry

We used FITC-, PE-, PerCP-, APC-, PE-Cychrome 7–, APC Cychrome 7-, and Pacific Blue–conjugated antibodies directed to human CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45, CD62L, CD45RA, CD95, CD127, CD138, CD38, CD27, CD28, Vβ13.1, Vβ21.3, and HLA-A2. NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer PE was used following the manufacturer’s instructions. Murine leukocytes were identified by antibodies to murine CD45. To measure CD127 expression, cells were washed and cultured in the absence of cytokines for 18 hours before staining. Cells (5 × 105) were incubated with antibodies for 15 minutes at 4°C and washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% FBS. Samples were run through a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) Canto II flow cytometer, and data were analyzed by Flow Jo software.

Functional assays

In 51Cr release assay, effectors were incubated with radiolabeled target cells at different effector/target (E/T) ratios for 4 hours. Specific lysis was expressed according to the following formula: 100 × (average experimental counts per minute [cpm] − average spontaneous cpm)/(average maximum cpm − average spontaneous cpm).

Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) release Elispot was performed plating responders and stimulators for 18 hours in Multiscreen HTS 96-well filtration plates (2 × 104 cells per well), at a stimulator-to-responder ratio of 1, as described.10

In coculture experiments, lymphocytes were cocultured with target cells at the E/T ratio of 1:5. At day 4, viable cells were counted and percentages of T cells, and targets were assessed by FACS. The elimination index was calculated as follows: 1 − (number of residual target cells in presence of NY-ESO-1 redirected T cells)/(number of residual target cells in presence of mock-transduced T cells).

In vivo studies

The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of San Raffaele Scientific Institute. Sublethally irradiated 10- to 12-week-old female NSG mice were first infused with U266 cells and after 30 to 40 days treated with engineered lymphocytes, cultured for a median of 22 days. Medium only and donor-matched mock-transduced lymphocytes were controls. Lymphocytes were phenotyped before infusion.

In vivo BLI optical imaging

A luciferase-expressing U266 line (U266luc) was generated by transducing U266 with a bidirectional LV coexpressing LNGFR and Firefly luciferase (luc2) followed by FACS. U266luc behaved similarly to the parental line in mice.

Small animal bioluminescence imaging (BLI) was performed with IVIS SpectrumCT System. Each mouse received an intraperitoneal injection of 150 mg luciferin/kg 10 minutes before BLI. The highest BLI signal was detected 15 minutes after luciferin injection. Images were obtained using the following IVIS settings: exposure time = auto, binning = 8, f = 1, and a field of view equal to 19.5 cm (field D). Dark measures were performed before BLI acquisition and subtracted from the acquired images, and no emission filters were used during BLI acquisitions. BLI image analysis was performed by placing a region of interest over the lesions and by measuring the total flux (photons/seconds) within the region of interest. Images were acquired and analyzed with Living Image 4.4.

Histology

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were cut at 4-µm-thick sections, stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and underwent blind histopathological examination by an expert hematopathologist. The degree of tissue infiltration by human lymphocytes was assessed with a semiquantitative modality on a 4 scale-degree (0 to 3) and further confirmed by immunohistochemistry. For immunohistochemical stains, anti-human CD3 rabbit monoclonal antibody (clone 2GV6) was furnished by prediluted dispenser within Ventana Medical Detection System. Antigen retrieval was performed by Ventana Roche solution for 20 minutes at pH 9.

Statistical analyses

We relied on descriptive statistics or compared the data sets by 2-tailed Student t tests, 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Log rank was used to compare survival curves. The statistical software packages GraphPad Prism version 7.0 and SPSS version 16.0 were used.

Results

NY-ESO-1–redirected stem memory and central memory T cells are efficiently generated by single TCR gene editing

To develop a clinically feasible protocol of TCR gene editing, T lymphocytes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) harvested from healthy donors were activated as previously reported25-27 and redirected against NY-ESO-1 through 3 separate manipulation protocols described in Figure 1A. Transduction efficiency with the NY-ESO-1 TCR-LV was 69.4% (±1.7; range 55-86) and was similar in TR and SE procedures (73.3% and 67.1%, respectively; Figure 1B), confirming that initial disruption of 1 endogenous TCR chain gene does not impair sensitivity to further LV transduction. For the SE protocol, we compared TRAC and TRBC disruption, which proved equally feasible (supplemental Figure 1). For further studies, we focused on TRAC SE. The efficiency of ZFN-mediated knockdown of the endogenous TRAC gene was 43.1% (±4.9; range 18-66) with AdVs and 57.2% (±4.3; range 33-81) with mRNA electroporation. Further experiments were performed using mRNA electroporation. Although the first 2 steps of genetic manipulation required for CE were highly efficient, the efficiencies of the third and fourth genetic steps, performed after T-cell restimulation, were significantly lower. By the end of the procedure the mean fold changes of NY-ESO-1 TR, SE, and CE lymphocytes calculated over initial counts were 11.6, 5.6, and 0.9, respectively (Figure 1C). The simplification of the editing strategy thus ensured a production of a high number of NY-ESO-1–redirected cells in 2 weeks.

Interestingly, our protocol favors the maintenance of an early differentiated phenotype, with a pronounced prevalence of stem memory (TSCM-CD45RAposCD62LposCD95pos) and central memory (TCM-CD45RAnegCD62LposCD95pos) lymphocytes (Figure 2A-B). Of note, similar distributions of memory T-cell subsets were observed in mock-transduced, TR, SE, and CE cells, indicating that the stimulation and culture protocol dominates over the genetic manipulation in determining cell differentiation fate. TSCM and TCM were equally represented in redirected CD4 cells, whereas TSCM was the most prevalent subset in CD8 lymphocytes. The early differentiation phenotype of gene-modified lymphocytes was further confirmed in all T-cell subgroups by the high proportion of cells expressing CD127, a biomarker of T-cell fitness and persistence28 (Figure 2C). The proportion of double-positive CD27 and CD28 T cells did not differ in mock-transduced (74% ± 5), TR (82% ± 5), and SE (80% ± 10) cells (Figure 2D), whereas it proved significantly lower in CE lymphocytes (37% ± 3), indicating that the length and complexity of the CE procedure might affect the composition of the cellular product. Interestingly, 49% of CE cells were CD28neg but expressed CD27, a molecule associated with long persistence in adoptive transfer protocols.29-31 This was particularly evident for CD8 T cells (supplemental Figure 2).

NY-ESO-1 edited lymphocytes express high TCR levels and display a preferential stem memory and central memory phenotype. (A) Distribution of T-cell subpopulations (TSCM, TCM, effector memory [TEM], and terminal effector [TEMRA]) within mock-transduced (mock-trd) and NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells: TR, SE, and CE. The analysis was performed by FACS, and the attribution to the 4 subgroups was made according to the expression of CD45RA, CD62L, and CD95 surface markers, as previously described.34 Histograms related to CD4pos and CD8pos T cells are shown. (B) Representative plots of CD45RA, CD62L, and CD95 expression on TCR redirected and mock-transduced T cells. PBMCs are shown as internal control. CD4 and CD8 subsets are separately shown. (C) Percentages of IL-7Rα (CD127) positive cells detected by FACS within CD3pos T cells and in separately gated CD4pos and CD8pos T cells. (D) Percentages of CD27- and/or CD28-expressing cells quantified by FACS and gated on CD3pos cells. Means and SEM of at least 4 healthy donors are presented. All data were acquired 4 to 5 weeks after S1. TR and SE cells were sorted by NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer before the analysis, as described in “Methods.” NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells were expanded by rapid expansion protocol, as previously described,24 and subsequently tested by flow cytometry for the expression of the NY-ESO-1157-165 Vβ13.1 chain (E) and for the specific binding to a NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer (F). Both histograms represent the relative fluorescent intensity (RFI) calculated as follows: (mean fluorescent intensity of TR, SE, and CE cells)/( mean fluorescent intensity of mock-trd cells). Analyses were performed on total CD3pos cells and on separately gated CD4pos and CD8pos cells. Means and SEM of 3 T-cell donors are presented. *P < .05 by paired Student t test.

NY-ESO-1 edited lymphocytes express high TCR levels and display a preferential stem memory and central memory phenotype. (A) Distribution of T-cell subpopulations (TSCM, TCM, effector memory [TEM], and terminal effector [TEMRA]) within mock-transduced (mock-trd) and NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells: TR, SE, and CE. The analysis was performed by FACS, and the attribution to the 4 subgroups was made according to the expression of CD45RA, CD62L, and CD95 surface markers, as previously described.34 Histograms related to CD4pos and CD8pos T cells are shown. (B) Representative plots of CD45RA, CD62L, and CD95 expression on TCR redirected and mock-transduced T cells. PBMCs are shown as internal control. CD4 and CD8 subsets are separately shown. (C) Percentages of IL-7Rα (CD127) positive cells detected by FACS within CD3pos T cells and in separately gated CD4pos and CD8pos T cells. (D) Percentages of CD27- and/or CD28-expressing cells quantified by FACS and gated on CD3pos cells. Means and SEM of at least 4 healthy donors are presented. All data were acquired 4 to 5 weeks after S1. TR and SE cells were sorted by NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer before the analysis, as described in “Methods.” NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells were expanded by rapid expansion protocol, as previously described,24 and subsequently tested by flow cytometry for the expression of the NY-ESO-1157-165 Vβ13.1 chain (E) and for the specific binding to a NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer (F). Both histograms represent the relative fluorescent intensity (RFI) calculated as follows: (mean fluorescent intensity of TR, SE, and CE cells)/( mean fluorescent intensity of mock-trd cells). Analyses were performed on total CD3pos cells and on separately gated CD4pos and CD8pos cells. Means and SEM of 3 T-cell donors are presented. *P < .05 by paired Student t test.

The editing process enhances NY-ESO-1 TCR expression in redirected T cells

After sorting for dextramerpos cells (with purity ≥97%), and expansion through a previously described protocol,24 we quantified NY-ESO-1 TCR surface expression upon staining with a TCR Vβ13.1 family–specific antibody and with a PE-conjugated HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer. Notably, although no differences emerged from the expression of TCR Vβ13.1 among TR, SE, and CE cells (Figure 2E), dextramer binding was significantly higher in edited T cells than in the TR counterpart (Figure 2F; supplemental Figure 3). These differences also emerged when separately analyzing CD4 and CD8 subsets, although the dextramer relative fluorescence intensity was significantly higher in CD8 than in CD4 cells (P < .05), because of higher stability of the TCR-major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) binding in the presence of CD8.32 Interestingly, the average vector copy numbers were 10 and 4 for TR and SE cells, respectively (supplemental Figure 4), indicating that the lower level of TCR expression on TR cells is not because of a lower vector copy number but possibly to competition of the NY-ESO-1 TCR with the endogenous TCR repertoire and/or mispaired TCRs. The similar levels of NY-ESO-1 TCR expression in CD4 and CD8 SE and CE lymphocytes suggest that the exogenous β chain properly pairs with the exogenous α chain with similar efficiency in SE and CE cells, and with more efficiency than in TR cells, thus suggesting that some degree of mispairing between endogenous and exogenous TCR chains occurs in conventionally TR cells. Noticeably, with this set of experiments we cannot rule out residual mispairing within the endogenous β chains and the exogenous α chain in SE cells. We then investigated efficacy and specificity of redirected T cells.

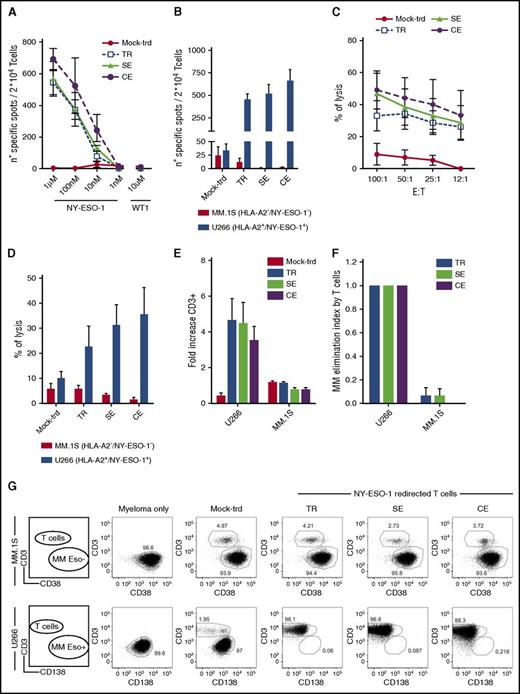

NY-ESO-1157-165-TCR–expressing cells specifically recognize and kill NY-ESO-1pos targets

We challenged TCR-redirected T cells and mock-transduced lymphocytes with T2 cells pulsed with decreasing concentrations of the NY-ESO-1157-165 peptide or with the irrelevant WT1126-134 HLA-A2 restricted peptide, the U266 (HLA-A2pos, NY-ESO-1pos), and the MM.1S (HLA-A2neg, NY-ESO-1neg) MM cell lines by IFN-γ Elispot, 51Cr release, and 4-day coculture.

A high frequency of TR, SE, and CE cells produced IFN-γ in the presence of NY-ESO-1157-165 pulsed T2 cells and of U266, naturally processing the tumor antigen (Figure 3A-B), with a trend in favor of TCR edited cells. Expression of both restriction element and antigen were required for recognition from redirected T cells (supplemental Figure 5).

NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells efficiently kill MM cells. Shown are results from TCR TR, SE, CE, and untransduced lymphocytes (mock-trd) cells tested by IFN-γ Elispot assay against T2 cells pulsed with decreasing concentrations of the NY-ESO-1157-165 HLA-A2 restricted peptide or the irrelevant WT1126-134 HLA-A2 restricted peptide as negative control (A) or against U266 (HLA-A2pos and NY-ESO-1pos) and MM.1S (HLA-A2neg and NY-ESO-1neg; negative control) MM cell lines (B). Specific spots are shown on the y-axis as spots produced in the presence of stimulators minus the spots produced by the effectors alone. Mean and SEM are shown, at the E/T ratio of 1. (C-D) Cytotoxic assay with TCR edited, TR, and untransduced T cells. (C) Shown is the functional activity measured by a 51Cr release assay for the lysis of labeled T2 cells pulsed with a concentration of the NY-ESO-1157-165 HLA-A2 restricted peptide of 1 µM, at decreasing E/T ratios or against U266 and MM.1S (negative control) MM cell lines (D) at the E/T ratio of 50:1. Mean and SEM of the percentages of lysis are shown. (E-G) Four-day coculture assay. TCR TR, SE, CE, and untransduced lymphocytes were cultured with U266 or MM.1S (E/T ratio = 1:5). After 4 days, residual U266 cells (CD138pos/CD3neg), MM.1S cells (CD38pos/CD3neg), and T lymphocytes (CD138neg/CD38neg/CD3pos) were counted and analyzed by FACS. (E) Expansion of NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells and control untransduced T cells (mock-trd) in response to NY-ESO-1–expressing (U266) or nonexpressing (MM.1S) cells measured as fold increase at the end of culture. (F) Antimyeloma effect by T cells measured as elimination index (see “Methods”). Mean and SEM are shown. (G) Representative plots of T-cell coculture with MM.1S (upper panel) and U266 (lower panel) at the E/T ratio of 1:5. All functional studies have been performed with 3 distinct donors. TR and SE cells were sorted for high expression of the NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer before functional assays. All effectors were tested after 1 cycle of cell stimulation through a rapid expansion protocol.24

NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells efficiently kill MM cells. Shown are results from TCR TR, SE, CE, and untransduced lymphocytes (mock-trd) cells tested by IFN-γ Elispot assay against T2 cells pulsed with decreasing concentrations of the NY-ESO-1157-165 HLA-A2 restricted peptide or the irrelevant WT1126-134 HLA-A2 restricted peptide as negative control (A) or against U266 (HLA-A2pos and NY-ESO-1pos) and MM.1S (HLA-A2neg and NY-ESO-1neg; negative control) MM cell lines (B). Specific spots are shown on the y-axis as spots produced in the presence of stimulators minus the spots produced by the effectors alone. Mean and SEM are shown, at the E/T ratio of 1. (C-D) Cytotoxic assay with TCR edited, TR, and untransduced T cells. (C) Shown is the functional activity measured by a 51Cr release assay for the lysis of labeled T2 cells pulsed with a concentration of the NY-ESO-1157-165 HLA-A2 restricted peptide of 1 µM, at decreasing E/T ratios or against U266 and MM.1S (negative control) MM cell lines (D) at the E/T ratio of 50:1. Mean and SEM of the percentages of lysis are shown. (E-G) Four-day coculture assay. TCR TR, SE, CE, and untransduced lymphocytes were cultured with U266 or MM.1S (E/T ratio = 1:5). After 4 days, residual U266 cells (CD138pos/CD3neg), MM.1S cells (CD38pos/CD3neg), and T lymphocytes (CD138neg/CD38neg/CD3pos) were counted and analyzed by FACS. (E) Expansion of NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells and control untransduced T cells (mock-trd) in response to NY-ESO-1–expressing (U266) or nonexpressing (MM.1S) cells measured as fold increase at the end of culture. (F) Antimyeloma effect by T cells measured as elimination index (see “Methods”). Mean and SEM are shown. (G) Representative plots of T-cell coculture with MM.1S (upper panel) and U266 (lower panel) at the E/T ratio of 1:5. All functional studies have been performed with 3 distinct donors. TR and SE cells were sorted for high expression of the NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer before functional assays. All effectors were tested after 1 cycle of cell stimulation through a rapid expansion protocol.24

NY-ESO-1-TCR–expressing T cells efficiently and specifically killed HLA-A2pos, NY-ESO-1pos targets (Figure 3C-D), again with a trend in favor of edited cells as compared with TR cells.

Finally, all redirected T cells proliferated extensively when cocultured with U266 (Figure 3E) and proved able to efficiently kill nearly 100% of U266 cells with a calculated mean elimination index of 0.99 at an E/T ratio of 1:10 (Figure 3F-G). Overall, the coculture assay reveals the ability of T lymphocytes, in the absence of cytokines, to eliminate cancer cells in a 4-day time span, also at low E/T ratios (supplemental Figure 6), mimicking the unfavorable clinical setting. The same results were obtained upon coculture of redirected lymphocytes with NY-ESO-1157-165 peptide-pulsed T2 cells. Cytokine release and killing were extremely specific as shown by the negligible recognition of WT1126-134 pulsed T2 cells and of the NY-ESO-1neg MM.1S cells.

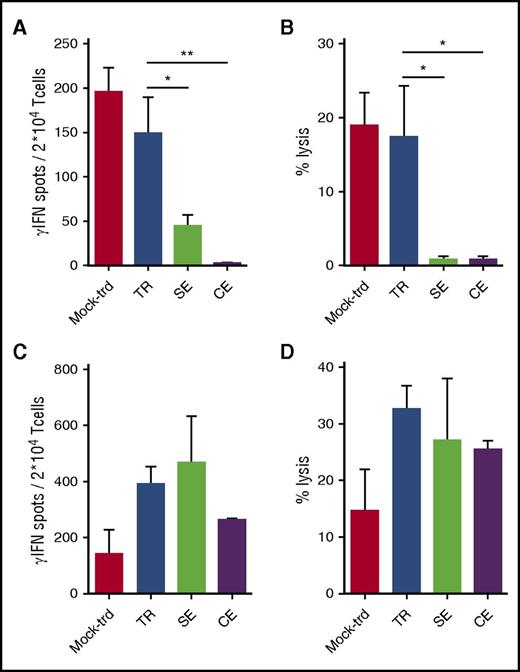

Alloreactivity of NY-ESO-1 TR T cells is abated in TCR gene-edited lymphocytes

To weigh the alloreactive potential of engineered lymphocytes, TCR-expressing cells and controls were stimulated with allogeneic irradiated PBMCs from 8 (4 HLA-A2neg and 4 HLA-A2pos) healthy donors in separate mixed lymphocyte cultures. After 2 cycles of stimulation, effectors were tested against PHA activated T cells from the same donors, autologous PHA lines, and NY-ESO-1157-165 pulsed HLA-A2pos (10 µM) irradiated cells in an IFN-γ Elispot (Figure 4A) and in a 51Cr release (Figure 4B) assays. No responses were observed against the autologous cells (not shown). SE and CE lymphocytes proved significantly less alloreactive than untransduced and TR counterparts in both functional assays, while they persisted in recognizing NY-ESO-1pos cells (Figure 4C-D). We further verified the alloreactivity of the SE protocol by performing TCR gene transfer, α SE and β SE with a TCR specific for the HLA-A0201 restricted WT1126-134 peptide.10 As shown in supplemental Figure 7, TR and SE cells proved equally able to recognize WT1pos targets. In accordance to the results obtained with NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells, α and β SE lymphocytes were significantly less alloreactive than TR cells. These results indicate that the abatement of alloreactivity observed with the editing process is not confined to a single TCR. To better investigate the basis of residual alloreactivity in SE T cells, we analyzed the expression of TCR Vβ families in the 4 cellular products. As expected, the expression of Vβ TCRs other than Vβ21.3 was consistently lower in α and β SE T cells than in TR cells. Interestingly, although in α SE T cells a residual expression was observed, in β SE cells this expression was almost abrogated. These results suggest that the potential residual alloreactivity of SE cells is not because of inefficient disruption of the endogenous repertoire, but instead to mispairing between the remaining TCR chain with the tumor-specific one. The ZFN-mediated disruption of one individual endogenous TCR chain not only eliminates the endogenous TCR repertoire, but also appears sufficient to significantly abate, although not abrogate, the risk of chain mispairing, responsible for unwanted unspecific reactivity. Overall, based on the encouraging results obtained in vitro with SE cells and considering the higher feasibility of the SE protocol compared with the CE one, we proceeded to the in vivo validation of the SE approach and compared its efficacy/safety profile with that of TCR gene transfer.

TR lymphocytes display higher alloreactivity than SE and CE T cells. TR, SE, CE T cells, and control mock-transduced (mock-trd) cells were separately plated in mixed lymphocyte reactions with irradiated allogeneic PBMCs. After 2 cycles of stimulation (S1, 10 days; S2, 7 days), effector cells were tested against a PHA cell line obtained from the same allogeneic targets and against the autologous cells in a IFN-γ Elispot (A) and in a 51Cr release (B) assay (shown is the E/T ratio of 50:1). No responses were observed against the autologous cells (not shown). Simultaneously, NY-ESO-1–redirected and mock-transduced T cells, stimulated as described previously, were tested against the HLA-A2pos T2 cell line pulsed with the NY-ESO-1157-165 peptide (C-D). Mean and SEM are shown. **P < .01; *P < .05, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.

TR lymphocytes display higher alloreactivity than SE and CE T cells. TR, SE, CE T cells, and control mock-transduced (mock-trd) cells were separately plated in mixed lymphocyte reactions with irradiated allogeneic PBMCs. After 2 cycles of stimulation (S1, 10 days; S2, 7 days), effector cells were tested against a PHA cell line obtained from the same allogeneic targets and against the autologous cells in a IFN-γ Elispot (A) and in a 51Cr release (B) assay (shown is the E/T ratio of 50:1). No responses were observed against the autologous cells (not shown). Simultaneously, NY-ESO-1–redirected and mock-transduced T cells, stimulated as described previously, were tested against the HLA-A2pos T2 cell line pulsed with the NY-ESO-1157-165 peptide (C-D). Mean and SEM are shown. **P < .01; *P < .05, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.

TCR SE T cells induce potent antitumor reaction in the absence of GVHD

We developed an experimental humanized-mouse preclinical model of MM (supplemental Figure 8). NY-ESO-1 TR and SE T cells and mock-transduced lymphocytes were IV infused in NSG mice 4 weeks after irradiation and tumor IV injection. One week after infusion, TR and SE cells expanded, reaching a peak at ∼7 days after injection (41% ± 9 and 23% ± 3 in TR and SE treated mice, respectively; P < .05) (Figure 5A). The initial T-cell expansion was associated with high amounts of human IFN-γ in animal sera, reaching peaks 1 day after T-cell infusion of 1480 pg/mL and 2003 pg/mL for TR and SE injected mice, respectively (P < .01; Figure 5B). Although mock-transduced and transferred T cells displayed a second wave of expansion and IFN-γ secretion, timely correlated with body weight loss, ruffled fur and hunchback, all animals infused with SE cells displayed a stable and low chimerism, low serum IFN-γ levels and a body weight similar to untreated littermates (Figure 5C).

NY-ESO-1 SE T cells mediate potent and specific antitumor activity in vivo. (A) Human T-cell chimerism in mice peripheral blood, calculated as follows: % of hCD3pos cells/ [(% of hCD3pos + % of mCD45pos cells) × 100], detected by flow cytometry. Mice had been injected with mock-transduced (mock-trd), TR and SE cells. Means and SEM are shown. *P <. 05 and **P < .01, by unpaired Student t test. (B) IFN-γ levels (pg/mL) detected in mice sera after infusion of mock-trd, TR, and SE cells. Means and SEM are shown. *P < .05 by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (C) Body weight variations, expressed as % and calculated as follows: body weight at each time point/[basal body weight recorded before U266 cell infusion × 100]. The panels correspond to animals treated with medium only (U266), mock-trd, TR, and SE T cells. Body weight kinetics of control littermates is also shown (ctrl). Each single replicate is shown. Horizontal dotted lines indicate the mean % body weight at the time of T-cell infusion. (D) U266 MM chimerism in bone marrow, calculated as follows: % of hCD138pos cells/[(% of hCD138pos + % of mCD45pos cells) × 100], detected by flow cytometry. Analyses of untreated mice (U266) and mock-trd, TR, and SE cells injected mice. Each single replicate, means, and SEM are shown. ***P < .005, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (E) Bioluminescence images of selected mice from the U266, mock-trd, TR, and SE T-cell treatment groups, obtained 1 week after treatment. A control mouse that did not receive either U266 or T cells is also included. (F) Noninvasive bioluminescence monitoring of MM growth in mice that received U266 but no T cells (purple dotted lines); mock-transduced T cells (red lines), NY-ESO-1 conventionally transferred T cells (blue lines), or NY-ESO-1 SE T cells (light green lines). Total flux expressed as photons/second and recorded from each mouse is shown.

NY-ESO-1 SE T cells mediate potent and specific antitumor activity in vivo. (A) Human T-cell chimerism in mice peripheral blood, calculated as follows: % of hCD3pos cells/ [(% of hCD3pos + % of mCD45pos cells) × 100], detected by flow cytometry. Mice had been injected with mock-transduced (mock-trd), TR and SE cells. Means and SEM are shown. *P <. 05 and **P < .01, by unpaired Student t test. (B) IFN-γ levels (pg/mL) detected in mice sera after infusion of mock-trd, TR, and SE cells. Means and SEM are shown. *P < .05 by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (C) Body weight variations, expressed as % and calculated as follows: body weight at each time point/[basal body weight recorded before U266 cell infusion × 100]. The panels correspond to animals treated with medium only (U266), mock-trd, TR, and SE T cells. Body weight kinetics of control littermates is also shown (ctrl). Each single replicate is shown. Horizontal dotted lines indicate the mean % body weight at the time of T-cell infusion. (D) U266 MM chimerism in bone marrow, calculated as follows: % of hCD138pos cells/[(% of hCD138pos + % of mCD45pos cells) × 100], detected by flow cytometry. Analyses of untreated mice (U266) and mock-trd, TR, and SE cells injected mice. Each single replicate, means, and SEM are shown. ***P < .005, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (E) Bioluminescence images of selected mice from the U266, mock-trd, TR, and SE T-cell treatment groups, obtained 1 week after treatment. A control mouse that did not receive either U266 or T cells is also included. (F) Noninvasive bioluminescence monitoring of MM growth in mice that received U266 but no T cells (purple dotted lines); mock-transduced T cells (red lines), NY-ESO-1 conventionally transferred T cells (blue lines), or NY-ESO-1 SE T cells (light green lines). Total flux expressed as photons/second and recorded from each mouse is shown.

Animal organs were analyzed at euthanization to reveal the presence of residual myeloma and/or pathological signs of GVHD.

Although mice receiving mock-transduced T cells displayed variable levels of myeloma infiltration in the bone marrow, all mice treated with NY-ESO-1 redirected T cells were completely tumor-free (Figure 5D). When we repeated the experiment with luciferase labeled U266, we observed that NY-ESO-1 redirected T cells act in a very short timeframe. Although 1 week after lymphocyte infusion untreated and mock-transduced treated animals showed variable levels of luminescence, indicative of the persistence of malignant cells, TR and SE infused mice were completely signal free (Figure 5E). Thus, early waves of IFN-γ secretion and T-cell expansion observed within the first week after adoptive transfer of TR and SE cells correlate with MM debulking. A stable complete remission was confirmed for 10 out of 11 animals treated with NY-ESO-1–redirected lymphocytes for up to 8 weeks (Figure 5F). One mouse, previously injected with SE cells, displayed an increase of total photon flux in the upper abdomen, starting from week 4 after treatment, in the absence of clinical signs. To investigate whether this observation was because of tumor immune evasion, as already described with U266 cells,33 we performed abdominal ultrasound, CT scan, and magnetic resonance. None of these techniques revealed abnormalities (not shown), and at necroscopy, no malignant cells could be detected either in bone marrow or in the abdominal cavity.

At the end of the experiment, although no differences were observed between TR and SE treated mice in terms of CD3pos marrow infiltration (Figure 6A), splenic infiltration by TR cells (50.5 ± 9) was higher than that of SE cells (23.1 ± 5.5), and similar to that of mock-transduced lymphocytes (48.5 ± 9.4) (Figure 6B). Such different behavior is consistent with a difference in the ability of TCR redirected cells to induce off-target toxicity in this experimental model. Accordingly, TR cells, despite efficiently clearing MM, induced a high rate of xenogeneic GVHD (74.3% of treated animals), resulting in lower overall and event free survival than those obtained with SE cells (Figure 6C-D). At the end of the experiments, all mice treated with SE cells were alive and well (overall survival: 26.7% vs 100% in TR and SE infused animals, respectively; P < .005). All untreated mice had to be killed before the end of the experiment because of disease progression. All animals infused with mock-transduced T cells required premature euthanization, because of either MM progression (3/15 animals presented extramedullary localizations), or xenogeneic GVHD, with 27% of animals showing signs of both MM and GVHD.

The TCR gene editing approach protects mice from GVHD and ensures a significant survival advantage over TCR gene transfer. Human T-cell chimerism in mice bone marrow (A) and spleen (B) at euthanization, calculated as follows: % of hCD3pos cells/[(% of hCD3pos + % of mCD45pos cells) × 100], detected by flow cytometry. Analysis of mock-transduced (mock-trd), TR, and SE cells injected mice. Each replicate and the means are shown. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .005 by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (C) Kaplan Meier curve showing overall survival of untreated (U266, dotted purple line) mice and animals injected with mock-trd (red line), TR (dotted blue line), and SE (light green line) cells. ***P < .005 by log-rank test. (D) Pie charts representing mouse outcome: at time of euthanization animals presented either in good clinical conditions and disease free (alive event-free, red), or with MM marrow infiltration (MM, blue), or with clinical and pathological signs of xenogeneic GVHD (light green), or with both U266 infiltration and GVHD (MM + GVHD, purple). The outcomes of the 4 treatment groups (U266, Mock-trd, TR, and SE) are shown. (E) Histopathological findings at euthanization. Analyses of skin, tongue, heart, lung, kidney, liver, and gut, collected at euthanization for each mouse, fixed in formalin and analyzed blinded by immunohistochemistry for T-cell infiltration. The pathological score ranged from 0 (completely healthy tissue, with no evidence of human T cells) to 3 (substantial and diffuse human lymphocyte infiltration, with subversion of the tissue architecture). Left panel: number of organs with T-cell infiltration (any grade)/mouse. For each animal a grade ranging from 0 to 7 was possible. Results on single animals and means are shown. Mock-trd, TR and SE treated mice are shown. ***P < .005, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Right panel: global pathological score for each individual mouse corresponding to the sum of all scores determined for each organ. Each value corresponds to a single animal. Means are also shown. Mock-trd, TR and SE treated mice are shown. ***P < .005, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.

The TCR gene editing approach protects mice from GVHD and ensures a significant survival advantage over TCR gene transfer. Human T-cell chimerism in mice bone marrow (A) and spleen (B) at euthanization, calculated as follows: % of hCD3pos cells/[(% of hCD3pos + % of mCD45pos cells) × 100], detected by flow cytometry. Analysis of mock-transduced (mock-trd), TR, and SE cells injected mice. Each replicate and the means are shown. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .005 by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (C) Kaplan Meier curve showing overall survival of untreated (U266, dotted purple line) mice and animals injected with mock-trd (red line), TR (dotted blue line), and SE (light green line) cells. ***P < .005 by log-rank test. (D) Pie charts representing mouse outcome: at time of euthanization animals presented either in good clinical conditions and disease free (alive event-free, red), or with MM marrow infiltration (MM, blue), or with clinical and pathological signs of xenogeneic GVHD (light green), or with both U266 infiltration and GVHD (MM + GVHD, purple). The outcomes of the 4 treatment groups (U266, Mock-trd, TR, and SE) are shown. (E) Histopathological findings at euthanization. Analyses of skin, tongue, heart, lung, kidney, liver, and gut, collected at euthanization for each mouse, fixed in formalin and analyzed blinded by immunohistochemistry for T-cell infiltration. The pathological score ranged from 0 (completely healthy tissue, with no evidence of human T cells) to 3 (substantial and diffuse human lymphocyte infiltration, with subversion of the tissue architecture). Left panel: number of organs with T-cell infiltration (any grade)/mouse. For each animal a grade ranging from 0 to 7 was possible. Results on single animals and means are shown. Mock-trd, TR and SE treated mice are shown. ***P < .005, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Right panel: global pathological score for each individual mouse corresponding to the sum of all scores determined for each organ. Each value corresponds to a single animal. Means are also shown. Mock-trd, TR and SE treated mice are shown. ***P < .005, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.

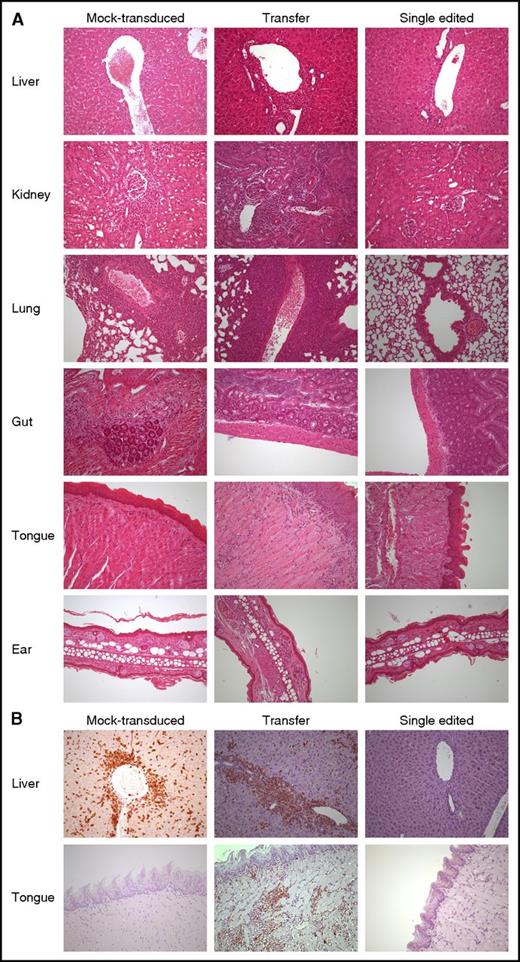

At euthanization, several organs (skin, tongue, heart, lung, kidney, liver, and gut) were collected, fixed in formalin, and blindly analyzed by immunohistochemistry for human T-cell infiltration. The number of organs showing T-cell infiltration was significantly higher in TR (mean 4) than in SE (mean 1) treated mice (Figure 6E, left panel). More importantly, the global pathological score, corresponding to the degree of T-cell infiltration for each organ, was also significantly higher in animals infused with nonedited T cells than in animals receiving SE cells (means of 6.2 and 1.9 for TR and SE, respectively; Figure 6E right panel). Figure 7 shows the differences in organ infiltration observed by hematoxylin-eosin staining and hCD3 immunostaining in representative samples.

SE abates the risk of organ infiltration by NY-ESO-1 redirected T lymphocytes. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded mouse tissues (liver, kidney, lung, gut, tongue, and ear) from 3 representative animals treated with mock-transduced (left column), transferred (middle column), and SE (right column) cells, respectively. Human lymphocytes displayed larger size when compared with their, albeit minimally present, animal counterpart. Liver involvement occurred mainly under the form of lymphocytic collections around major vessels as well as intraparenchimal nodules of variable size. In the kidney, along with perivascular arrangement, a periglomerular involvement was also encountered. Pulmonary localization was mainly around major vessels and peribronchial in a smaller proportion. In gut and ear, human lymphocytes occurred mostly under the form of few, scattered cells with subepithelial location. Interestingly, in the tongue, human lymphocytes displayed a superficial distribution, immediately beneath or exactly at dermo-epithelial junction, thus recapitulating a “graft-versus-host”–like pattern. The degree of tissue infiltration by human lymphocytes was assessed as described in “Methods” and further confirmed by immunohistochemistry with an anti-human CD3 rabbit monoclonal antibody (B). All pictures were taken at ×200 original magnification.

SE abates the risk of organ infiltration by NY-ESO-1 redirected T lymphocytes. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded mouse tissues (liver, kidney, lung, gut, tongue, and ear) from 3 representative animals treated with mock-transduced (left column), transferred (middle column), and SE (right column) cells, respectively. Human lymphocytes displayed larger size when compared with their, albeit minimally present, animal counterpart. Liver involvement occurred mainly under the form of lymphocytic collections around major vessels as well as intraparenchimal nodules of variable size. In the kidney, along with perivascular arrangement, a periglomerular involvement was also encountered. Pulmonary localization was mainly around major vessels and peribronchial in a smaller proportion. In gut and ear, human lymphocytes occurred mostly under the form of few, scattered cells with subepithelial location. Interestingly, in the tongue, human lymphocytes displayed a superficial distribution, immediately beneath or exactly at dermo-epithelial junction, thus recapitulating a “graft-versus-host”–like pattern. The degree of tissue infiltration by human lymphocytes was assessed as described in “Methods” and further confirmed by immunohistochemistry with an anti-human CD3 rabbit monoclonal antibody (B). All pictures were taken at ×200 original magnification.

Overall these results indicate that the potent antimyeloma activity of NY-ESO-1-TR lymphocytes is limited by a high alloreactive potential in vivo. Conversely, NY-ESO-1 SE cells exhibited high tumor specificity, resulting in optimal antitumor activity, in the absence of GVHD.

Discussion

Cancer immunotherapy and in particular chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy have produced a recent string of impressive clinical results. Gene transfer tools have been critical for reaching this phase of clinical development. Technological advancements today allow not only to add a gene and function to a target cell, but, thanks to the genome editing technology, to completely and permanently substitute 1 or more biological functions in a cell of choice. Coupling genome editing to cancer immunotherapy offers a unique opportunity to treat cancer patients with safe, effective and long-lasting therapeutic approaches. However, for a rapid and wide clinical translation, increased technological complexity should not impact on the manufacturing feasibility.

The complete TCR gene editing approach was designed to fully redirect T-cell specificity and significantly improved the efficacy and safety profile of TCR gene transfer.10 However, this was achieved through a 40-day manipulation protocol, requiring 2 steps of cell activation and 4 sequential steps of genetic engineering.

To improve the clinical feasibility of TCR gene editing, we describe here a single TCR gene editing approach, based on the disruption of the endogenous TCR α chain gene followed by the transfer of a tumor-specific TCR, in a single round of T-cell activation. This approach generates a large numbers of SE T cells in 2 weeks and is sufficient to abrogate the endogenous TCR repertoire. We show that this simplified highly feasible approach retains the advantages of the original TCR CE protocol, in vitro and in vivo.

The tumor antigen targeted in this work is the cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1, an attractive target for tumor immunotherapy because of its expression in high percentages of common tumors including high-risk MM, breast, lung, liver, esophago-gastric, prostate and ovarian cancers.17-19 The advantage of T-cell based cancer immunotherapy, when compared with alternative treatments, largely lies on the ability of T lymphocytes to persist long-term, promote tumor immune-surveillance and expand upon tumor recurrence. These features cluster within early differentiated (TSCM and TCM) lymphocytes.26,34-39 By coupling a T-cell manipulation protocol designed to preserve cellular fitness and functional properties of early differentiated T cells25-27 with TCR SE, we generated high numbers of NY-ESO-1–redirected TSCM and TCM. The editing process resulted in superior levels of NY-ESO-1 TCR expression compared with the TCR transfer protocol. This observation is particularly relevant considering that the overall avidity of a tumor-specific T cell depends not only on the affinity of the TCR for its HLA-peptide complex, but also on the level of TCR expression. The TCR that we employed is codon optimized and affinity enhanced.14,15,22,40 Overall such structural modifications ensured high tumor recognition in vitro and in vivo by both TCR gene transferred and TCR edited lymphocytes. Still, the aforementioned technological advances did not appear sufficient to abrogate alloreactivity of TR lymphocytes, that recognized and killed allogeneic targets in vitro and in vivo. Alloreactivity and GVHD are highly complex phenomena, difficult to model in vitro and in vivo.41 We compared the alloreactive potential of our different cellular products through mixed lymphocyte reactions and in a humanized mouse model. Although none of these models is fully representative of the human scenario, results were univocal. Transferred lymphocytes proved significantly more alloreactive than edited cells in vitro. Noticeably, similar results were observed by using a different tumor-specific TCR, indicating that the reduced alloreactivity observed with the editing process is not confined to a single TCR.

In our in vivo model, the detrimental alloreactive effect mediated by TR and mock-transduced lymphocytes, led to T-cell infiltrations and GVHD-like lesions in several tissues. Conversely, the full abrogation of the endogenous TCR repertoire in SE tumor redirected cells prevented off-target reactivity, while promoting a potent antitumor reaction. Overall, the rate of xenogeneic GVHD related mortality was 74.3% in mice treated with transferred lymphocytes while absent in mice receiving edited cells. Interestingly, in a clinical trial based on the infusion of NY-ESO-1 transferred lymphocytes to patients affected by MM, the development of skin and gut GVHD was recently reported in 3/20 patients,42 thus indicating that, even with this optimized TCR, toxicity is a threat also in the autologous platform.

We propose TCR SE as an innovative and feasible new approach for redirecting T-cell specificity. We expect to implement it in 3 clinical settings: autologous, matched allogeneic, third-party off-the-shelf, depending on the disease type and patient characteristics. The reduction of TCR mispairing is a valuable gain for all clinical platforms. On the other hand, the complete abrogation of the entire TCR endogenous repertoire allows to safely exploit TCR edited cells in the allogeneic context and represents a first step toward the generation of off-the-shelf cellular products.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of Bonini’s and Naldini’s laboratories for useful discussion and Laura Falcone and Margherita Norelli for support and discussion.

This work was supported by European Union Seventh Framework Programme (SUPERSIST, ATTACK) and by the Italian Association for Cancer Research, Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR). E.R. was supported by a fellowship by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro cofunded by the European Union.

Authorship

Contribution: S.M. designed the study, conducted laboratory experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; P.G. and G.S. designed and performed genetic manipulations of the T cells and participated in the design of the study, data discussion, and interpretation of results; Z.M. and E.L. conducted laboratory experiments and analyzed and interpreted data; E.R. conducted experiments with the WT1-specific TCR; B.C. participated in the in vivo experiments; M.R. processed pathological samples; M.P. performed histopathological examination; G.E. and B.G. constructed the U266-Luc cell line; A.S. performed bioluminescence acquisition and analysis; N.C., G.O., and A.M. participated in data discussion and interpretation of results on T-cell activation and phenotype; M.C. participated in coculture experiments and data discussion; A.L., E.P., A.B., L.V., F.C., and L.N. participated in data discussion and interpretation of results; A.R. and M.C.H. designed and implemented the ZFN pairs used in the study; and C.B. designed and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.R. and M.C.H. are employees of Sangamo Biosciences. C.B. had a research contract with Molmed S.p.A. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Chiara Bonini, Experimental Hematology Unit, Ospedale San Raffaele Scientific Institute, via Olgettina 60, Milano, Italy; e-mail: bonini.chiara@hsr.it.

![Figure 2. NY-ESO-1 edited lymphocytes express high TCR levels and display a preferential stem memory and central memory phenotype. (A) Distribution of T-cell subpopulations (TSCM, TCM, effector memory [TEM], and terminal effector [TEMRA]) within mock-transduced (mock-trd) and NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells: TR, SE, and CE. The analysis was performed by FACS, and the attribution to the 4 subgroups was made according to the expression of CD45RA, CD62L, and CD95 surface markers, as previously described.34 Histograms related to CD4pos and CD8pos T cells are shown. (B) Representative plots of CD45RA, CD62L, and CD95 expression on TCR redirected and mock-transduced T cells. PBMCs are shown as internal control. CD4 and CD8 subsets are separately shown. (C) Percentages of IL-7Rα (CD127) positive cells detected by FACS within CD3pos T cells and in separately gated CD4pos and CD8pos T cells. (D) Percentages of CD27- and/or CD28-expressing cells quantified by FACS and gated on CD3pos cells. Means and SEM of at least 4 healthy donors are presented. All data were acquired 4 to 5 weeks after S1. TR and SE cells were sorted by NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer before the analysis, as described in “Methods.” NY-ESO-1–redirected T cells were expanded by rapid expansion protocol, as previously described,24 and subsequently tested by flow cytometry for the expression of the NY-ESO-1157-165 Vβ13.1 chain (E) and for the specific binding to a NY-ESO-1157-165 dextramer (F). Both histograms represent the relative fluorescent intensity (RFI) calculated as follows: (mean fluorescent intensity of TR, SE, and CE cells)/( mean fluorescent intensity of mock-trd cells). Analyses were performed on total CD3pos cells and on separately gated CD4pos and CD8pos cells. Means and SEM of 3 T-cell donors are presented. *P < .05 by paired Student t test.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/5/10.1182_blood-2016-08-732636/4/m_blood732636f2.jpeg?Expires=1769176718&Signature=MDYeRhCF7K0fzys5daknrXfYy99GtdEatLJ2-mgkBJXAWTn2rooB5Oa2u66T9V7TzezT2wqB415Gbfj3CUxbeWRvdUX-njn260nrAiDlSkguDelBrWMReXnHKevyroAxSF2wKsbVoY5YW2d7qzmHIpAtcVxs3ZHwKwIPijlMjZ-XsTUwr2cge1DYkvGlXeEPV5NkIfs5RJbWIXJDdHLqnQXHroQ6PDEMrENgE8pxgO~X8HDEoD3jldgAuGSG-T3pk46oEq8twKkHV-qeeqmrc9rS~AAogtPLOINqqSvGLoRP~YOEbEjjBZLOtm-00g288StSI1RpKd4jtOg09gnMjA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. NY-ESO-1 SE T cells mediate potent and specific antitumor activity in vivo. (A) Human T-cell chimerism in mice peripheral blood, calculated as follows: % of hCD3pos cells/ [(% of hCD3pos + % of mCD45pos cells) × 100], detected by flow cytometry. Mice had been injected with mock-transduced (mock-trd), TR and SE cells. Means and SEM are shown. *P <. 05 and **P < .01, by unpaired Student t test. (B) IFN-γ levels (pg/mL) detected in mice sera after infusion of mock-trd, TR, and SE cells. Means and SEM are shown. *P < .05 by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (C) Body weight variations, expressed as % and calculated as follows: body weight at each time point/[basal body weight recorded before U266 cell infusion × 100]. The panels correspond to animals treated with medium only (U266), mock-trd, TR, and SE T cells. Body weight kinetics of control littermates is also shown (ctrl). Each single replicate is shown. Horizontal dotted lines indicate the mean % body weight at the time of T-cell infusion. (D) U266 MM chimerism in bone marrow, calculated as follows: % of hCD138pos cells/[(% of hCD138pos + % of mCD45pos cells) × 100], detected by flow cytometry. Analyses of untreated mice (U266) and mock-trd, TR, and SE cells injected mice. Each single replicate, means, and SEM are shown. ***P < .005, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (E) Bioluminescence images of selected mice from the U266, mock-trd, TR, and SE T-cell treatment groups, obtained 1 week after treatment. A control mouse that did not receive either U266 or T cells is also included. (F) Noninvasive bioluminescence monitoring of MM growth in mice that received U266 but no T cells (purple dotted lines); mock-transduced T cells (red lines), NY-ESO-1 conventionally transferred T cells (blue lines), or NY-ESO-1 SE T cells (light green lines). Total flux expressed as photons/second and recorded from each mouse is shown.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/5/10.1182_blood-2016-08-732636/4/m_blood732636f5.jpeg?Expires=1769176718&Signature=c060cOcrvI3oR1R-6E7E2mKyw~AXobhFuibNOpwL~Lh0MQ8b8TEcuqTbiLkrDjvVmpU2kxLQ7jz0CnQwNHJ8TEoqwsmqW0O7k1NAkbHwoS1jc0s7A~B5SCA635A5DDbUwaQySnrtkrQIfIZevlIsrT9616uA1Hv5~2U1fwIeaqg6KzzCioM7Npl67MhatO7beVOWG4w0Z~vpsnfNaRD2TMfZiydk~n04pefdJ46WGNgTXw9pNj1OWfcCeeGERTTZ6qWliF75ymCMGZEjJOiWnVzEyKmxYbVwNrJqd0fAZ7kYlWwVzvJdEmj~9~umi9qU67ezM9jD47j3oVd1ZJ~lIg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. The TCR gene editing approach protects mice from GVHD and ensures a significant survival advantage over TCR gene transfer. Human T-cell chimerism in mice bone marrow (A) and spleen (B) at euthanization, calculated as follows: % of hCD3pos cells/[(% of hCD3pos + % of mCD45pos cells) × 100], detected by flow cytometry. Analysis of mock-transduced (mock-trd), TR, and SE cells injected mice. Each replicate and the means are shown. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .005 by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. (C) Kaplan Meier curve showing overall survival of untreated (U266, dotted purple line) mice and animals injected with mock-trd (red line), TR (dotted blue line), and SE (light green line) cells. ***P < .005 by log-rank test. (D) Pie charts representing mouse outcome: at time of euthanization animals presented either in good clinical conditions and disease free (alive event-free, red), or with MM marrow infiltration (MM, blue), or with clinical and pathological signs of xenogeneic GVHD (light green), or with both U266 infiltration and GVHD (MM + GVHD, purple). The outcomes of the 4 treatment groups (U266, Mock-trd, TR, and SE) are shown. (E) Histopathological findings at euthanization. Analyses of skin, tongue, heart, lung, kidney, liver, and gut, collected at euthanization for each mouse, fixed in formalin and analyzed blinded by immunohistochemistry for T-cell infiltration. The pathological score ranged from 0 (completely healthy tissue, with no evidence of human T cells) to 3 (substantial and diffuse human lymphocyte infiltration, with subversion of the tissue architecture). Left panel: number of organs with T-cell infiltration (any grade)/mouse. For each animal a grade ranging from 0 to 7 was possible. Results on single animals and means are shown. Mock-trd, TR and SE treated mice are shown. ***P < .005, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Right panel: global pathological score for each individual mouse corresponding to the sum of all scores determined for each organ. Each value corresponds to a single animal. Means are also shown. Mock-trd, TR and SE treated mice are shown. ***P < .005, by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/5/10.1182_blood-2016-08-732636/4/m_blood732636f6.jpeg?Expires=1769176718&Signature=iRe57YGFhNDH0gLWXlKh8a1z5IdlK-Qp2qGe9pN6vQDKFqY7zwkMDe038ytwY-iAVu-NLVqMCiQojhw9KGNh-rEy6SQr5WzoAVjBehO7vMyDMNs8Ya1ZyySjxjx9XZ~9adjbQCo~QpSXWtjA1DWEolmQ66FiRafcovrl-nppPHrK1A-fX21nvwrTFpJkn7GT9ltb1V1Pey~limuKE0mW6CLun6s5m-0Q92oUyVYrdYJ88JlXeI6ZdnWDEC2qSa48FMYr8WG2XWJuiUjzeHUDrD7xVb1cykRvym5VFdAmrJ-As07bu6fTAgyhybIG7YpjZ49SY5MWNOB~JTFpj-ex8Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)