Abstract

The majority of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) are cured with initial therapy. However, high-dose therapy with autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (AHCT) allows for the cure of an additional portion of patients with relapsed or primary refractory disease. Positron emission tomography–negative complete remission before AHCT is critical for long-term disease control. Several salvage options are available with comparable response rates, and the choice can be dependent of comorbidities and logistics. Radiation therapy can also improve the remission rate and is an important therapeutic option for selected patients. Brentuximab vedotin (BV) maintenance after AHCT is beneficial in patients at high risk for relapse, especially those with more than 1 risk factor, but can have the possibility of significant side effects, primarily neuropathy. Newer agents with novel mechanisms of action are under investigation to improve response rates for patients with subsequent relapse, although are not curative alone. BV and the checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab are very effective with limited side effects and can bridge patients to curative allogeneic transplants (allo-HCT). Consideration for immune-mediated toxicities, timing of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant based on response, and the potential for increased graft-versus-host disease remain important. Overall, prospective investigations continue to improve outcomes and minimize toxicity for relapsed or primary refractory HL patients.

Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a highly treatable malignancy with 85% to 90% of early-stage and 70% to 80% of advanced-stage patients cured after initial therapy.1-4 For the portion of patients who relapse or have refractory disease (rrHL), 2 randomized trials established salvage chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (AHCT) as standard of care resulting from improved progression-free survival (PFS).5,6 A variety of salvage programs have been developed, but because no option has yielded vastly distinctive results, newer trials have incorporated novel agents into these regimens. Similarly, a standard conditioning chemotherapy pre-AHCT has not been established, although incorporation of radiation therapy can improve outcomes in patients without extranodal disease, and overall long-term disease control is accomplished in at least 50% of patients.7

Risk factors for early relapse after AHCT have been extensively studied and include initial remission duration of <1 year or primary refractory disease, extranodal involvement, or advanced-stage disease at relapse, lack of chemosensitivity to salvage therapy, and the presence of residual [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) activity by positron emission tomography (PET).8-12 Because of the improvement in outcomes, brentuximab vedotin (BV) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for maintenance therapy after AHCT in patients with risk factors for early progression. Many novel agents are under investigation for relapse after AHCT, with the initial approval of BV and the recent FDA approval of the checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) nivolumab and pembrolizumab of most importance.13-15 Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (allo-HCT) with reduced intensity conditioning traditionally can then offer the next potential for cure. With the availability of haploidentical and cord blood sources, virtually all patients will have a donor, and this is no longer a limiting factor to allo-HCT.16-20 Instead, considerations of timing, efficacy, and toxicity are paramount.

We focus this review on the importance of pre-AHCT PET response, the choice of newer salvage therapies before AHCT to achieve that response, AHCT conditioning and maintenance, novel therapies for relapse after AHCT, and modern considerations around allo-HCT.

Pre-AHCT PET response

Functional imaging response after salvage therapy is the most important prognostic factor for long-term disease control. Most often, this is evaluated by FDG PET scanning to differentiate viable tumor from residual fibrotic tissue. Moskowitz et al reported on HL patients treated on sequential salvage therapy trials with a 5-year event-free survival (EFS) of 31% vs 75% for functional imaging–positive and negative patients, respectively (with similar results for patients who received PET scans or gallium scans).21 Similarly, for primary refractory disease, the 10-year EFS for patients with a negative PET after salvage was 68% vs 33% for PET-positive patients.8

A meta-analysis of 11 studies including 745 HL patients with pre-AHCT PET scans found that PFS ranged between 0% and 52% in PET-positive patients compared with 55% to 85% in PET-negative patients.22 Furthermore, overall survival (OS) was 17% to 77% in PET-positive patients vs 78% to 100% in PET-negative patients, with the varying results likely resulting from the population of patients included and the availability of salvage options. In addition, the studies included used several different criteria for determining PET negativity, primarily the Deauville scoring23 and the International Harmonization Project.24 Important to note is that not all PET-negative patients are cured, whereas some PET-positive patients are. Therefore, curative therapeutic options should be considered for all patients.

Prior studies often relied on visual scoring for determination of remission status. To allow for standardization of interpretation of PET scans, the 5-point Deauville criteria were developed.25 Scores of 4 and 5 are defined as a positive scan with additional intervention needed for those patients; however, alternatives to standardized uptake values as the primary measure of tumor burden are in development. Recently, metabolic tumor volume (MTV) has been shown to be prognostic in a PET-adapted treatment setting.26 MTV is determined by a combination of manual and computerized drawing of 3-dimensional areas of FDG-avid regions on PET and then summing the results.27 In the study, the optimal cutoff for baseline MTV was 109.5 cm3. Using this cutoff, patients with low MTV had a 3-year EFS of 92% vs 27% for those with high MTV.

Finally, Kapke et al published on routine surveillance imaging to monitor for relapse after AHCT.28 Similar to other surveillance imaging studies, they found that the median time to relapse and median postrelapse survival were not significantly different between patients whose relapse was detected clinically or radiographically. They conclude that there is limited utility for post-AHCT imaging for patients who have achieved complete remission (CR).

Recommendation

Achieving a PET-negative CR before AHCT is important, and outcomes are excellent in those patients. However, because up to 40% of patients with a positive scan are cured, AHCT should not be withheld especially with the addition of BV maintenance, as described in the following section. Strategies for additional therapy to achieve PET negative CR before AHCT will be discussed in next.

Salvage therapy before AHCT

Combination chemotherapy including either ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE); dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (DHAP); etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (ESHAP); gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin; gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin (GVD); and ifosfamide, gemcitabine, etoposide have been standard salvage therapy programs with no one better than the other. More recently, novel agents have been incorporated to achieve better complete response rates before AHCT, given the importance of PET negativity. We describe a few options, with the data summarized in Table 1.

Outcomes of selected salvage therapy programs

| Regimen . | N . | Rel . | Primary ref . | CR-PET neg pre-AHCT, % . | CD34+ cells/kg collected, × 106 . | AHCT, % . | PFS ITT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV → sequential ICE29 | 66 | 33 | 33 | 73 | 6.2 | 95 | 79% at 3 y |

| BV → sequential salvage therapy30 | 37 | 13 | 24 | 73 | 5.6 | 89 | 72% at 1.5 y |

| BV-ESHAP32 | 66 | 26 | 40 | 70 | 5.75 | 92 | NA |

| Benda-BV34 | 54 | 27 | 27 | 74 | 4 | 74 | 63% at 2 y |

| BV-ICE31 | 16 | 5 | 11 | 69 | 11 | 75 | NA |

| BV-DHAP33 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 90 | 5.3 | 100 | NA |

| BV-Nivo35 | 62 | 34 | 28 | 64 | 4.7 | 46 | NA |

| ICE/GVD79 | 97 | 56 | 41 | 76 | 6.3 | 88 | 68% at 8 y |

| BeGV36 | 59 | 27 | 32 | 73 | 8.8 | 73 | 63% at 2 y |

| ICE80 | 65 | 45 | 20 | 26* | 7 | 85 | 58% at 2 y |

| DHAP81 | 102 | 86 | 16 | 21* | 6.1 | NA | NA |

| GVD37 | 51 | NA | NA | 20* | NA | 76 | 52% at 4 y |

| Regimen . | N . | Rel . | Primary ref . | CR-PET neg pre-AHCT, % . | CD34+ cells/kg collected, × 106 . | AHCT, % . | PFS ITT . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV → sequential ICE29 | 66 | 33 | 33 | 73 | 6.2 | 95 | 79% at 3 y |

| BV → sequential salvage therapy30 | 37 | 13 | 24 | 73 | 5.6 | 89 | 72% at 1.5 y |

| BV-ESHAP32 | 66 | 26 | 40 | 70 | 5.75 | 92 | NA |

| Benda-BV34 | 54 | 27 | 27 | 74 | 4 | 74 | 63% at 2 y |

| BV-ICE31 | 16 | 5 | 11 | 69 | 11 | 75 | NA |

| BV-DHAP33 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 90 | 5.3 | 100 | NA |

| BV-Nivo35 | 62 | 34 | 28 | 64 | 4.7 | 46 | NA |

| ICE/GVD79 | 97 | 56 | 41 | 76 | 6.3 | 88 | 68% at 8 y |

| BeGV36 | 59 | 27 | 32 | 73 | 8.8 | 73 | 63% at 2 y |

| ICE80 | 65 | 45 | 20 | 26* | 7 | 85 | 58% at 2 y |

| DHAP81 | 102 | 86 | 16 | 21* | 6.1 | NA | NA |

| GVD37 | 51 | NA | NA | 20* | NA | 76 | 52% at 4 y |

BeGV, bendamustine, gemcitabine, vinorelbine; Benda, bendamustine; NA, not yet available; Nivo, nivolumab; ref, refractory; rel, relapsed.

Computed tomography criteria (no functional imaging included because of study timeframe).

BV is an antibody drug conjugate with a recombinant chimeric immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody against CD30 covalently linked to monomethyl auristatin E. In the cell, monomethyl auristatin E is cleaved and acts as an antimicrotubule agent, causing apoptosis. BV has been incorporated into salvage therapy in both sequential and combinatorial strategies. Importantly, the addition of BV did not add significant additional toxicities in these studies and stem cell collection was successful in almost all cases.

Two studies have evaluated BV sequential with chemotherapy. In the first, BV was given at 1.2 mg/kg weekly for 3 weeks every 28 days. A PET-adapted approach was used in patients with negative PET after 2 to 3 cycles of BV (28%, Deauville 1-2) who proceeded directly to AHCT, whereas the rest received augmented ICE, with 70% of those achieving PET normalization.29 Grade 3-4 adverse events included hyperglycemia (4%), hypoglycemia (4%), hypocalcemia (4%), and nausea (2%). All except for 1 patient, who was lost to follow-up, proceeded to AHCT with an intention-to-treat (ITT) PFS of 79% at 3 years. Similarly, when BV was administered at standard 1.8 mg/kg every-3-week dosing, 35% of the patients were in CR after BV, with an additional 38% with PET-negative CR after combination chemotherapy.30 Side effects were again minimal. ITT PFS was 72% at 18 months.

Standard salvage combinations incorporating BV at the same time as the chemotherapy include ICE,31 BV-ESHAP,32 and DHAP33 (Table 1). Preliminary results show complete response rates between 69% to 90%, with 75% to 100% of patients proceeding to AHCT. Longer follow-up is needed, but these results do not show dramatic differences in CR rates with the addition of BV.

Bendamustine is a nitrogen mustard derivative that has also been combined with BV.34 Patients received 1.8 mg/kg BV on day 1 with bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 of 3-week cycles for up to 6 cycles. Infusion-related reactions were common until premedications were required. The CR rate was 74% with an overall response rate (ORR) of 93%. Stem cell collection was successful in 93% of the patients after mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and plerixafor. The estimated 1-year PFS was 80% for both the transplanted and the overall population.

Nivolumab has been combined with BV in a phase 1/2 study for rrHL after frontline therapy.35 Interim results of the 62 patients who have completed treatment demonstrated an 85% ORR with 64% CR and with 29 proceeding to AHCT, with no unusual posttransplant toxicities. Infusion reactions were frequent, prompting the need for premedication. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) occurred in 72%, with 7% grade 3 or higher (grade 4 pneumonitis, grade 3 diarrhea, and grade 3 transaminitis). One patient had grade 3 hypercalcemia and acute kidney injury.

A newer non–BV-based outpatient salvage regimen is bendamustine, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine with gemcitabine 800 mg/m2 on days 1 and 4, vinorelbine 20 mg/m2 on day 1, and bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 2 and 3, and prednisolone 100 mg/day on days 1 to 4.36 After 4 cycles of therapy, the ORR was 83%, with 73% CR. The most common grade 3 to 4 toxicities included neutropenia (13.5%; febrile neutropenia, 12%), thrombocytopenia (13.5%), and infection (7%). Forty-three of the 59 patients proceeded to AHCT with the ITT 2-year PFS and OS of rates 62% and 78%, respectively.

An important consideration in the choice of regimens is the side effect profile given the similar response rates. Formal quality of life (QoL) measurements have not been reported from the salvage trials, but have been reported from the Phase 3 Study of Brentuximab Vedotin (SGN-35) in Patients at High Risk of Residual Hodgkin Lymphoma Following Autologous Stem Cell Transplant (AETHERA) study for BV37 and from the CheckMate 205 trial for nivolumab,38 as discussed later. Overall, these agents have not had significant detriments to QoL in most patients.

Recommendation

Patients can receive up to 2 salvage programs (including radiation) to achieve PET-negative CR pre-AHCT. Because most salvage options yield similar results, choice of salvage therapy is dependent on comorbidities and logistics. However, we recommend a sequential approach with single-agent brentuximab vedotin as the first option to spare patients from the long-term toxicities of additional combination chemotherapy if possible. If unable to obtain BV in this setting because of insurance constraints, we would recommend standard platinum-based salvage and only use BV as part of second salvage therapy if a suboptimal response is achieved to standard programs such as ICE or DHAP.

AHCT conditioning and maintenance

The goal of an AHCT is to deliver high-dose chemotherapy to target residual lymphoma cells, with the stem cell infusion as rescue. The optimal conditioning regimen has not been determined, but carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM) and carmustine, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide (CBV) are most frequently used in the United States. The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research completed a registry analysis of the outcomes for lymphoma patients treated with these conditioning regimens as well as busulfan and cyclophosphamide (BuCy) and total body irradiation (TBI)-containing regimens.39 CBV was used more frequently for HL patients, but over time, there was a shift toward BEAM. A higher mortality was seen in the non-BEAM regimens for HL patients compared with BEAM (CBV high: hazard ratio [HR], 1.54; CBV low: HR, 1.53; BuCy: HR, 1.77; and TBI: HR, 3.39, P < .001). There was no difference in treatment-related mortality, but an increased risk of relapse for the non-BEAM or CBV regimens. Three-year PFS and OS were BEAM 62% and 79%, CBV low 60% and 73%, CBV high 57% and 68%, BuCy 51% and 65%, and TBI 43% and 47%, respectively. HL was associated with the development of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome and occurred more frequently in the non-BEAM patients.

There are many alternatives to these standard conditioning regimens.40 Modifications were made because of the unavailability of carmustine in some areas as well as trying to improve efficacy or toxicity, although superiority has not been demonstrated for any option. Possibilities include etoposide and melphalan, gemcitabine, busulfan, and melphalan, and a variety of substitutions for the carmustine in BEAM including bendamustine,41 fotemustine, lomustine, mitoxantrone, and thiotepa. Additionally, Paulson et al presented data from the Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group evaluating non–carmustine-based regimens given the 5000% increase in price for carmustine in Canada over the past 5 years.42 When they compared BEAM with melphalan 200 mg/m2, single-agent, or melphalan and etoposide, they found no difference in OS, PFS, or nonrelapse mortality.

Radiation therapy (RT) can be incorporated pre-AHCT as part of conditioning or post-AHCT, but there are no randomized data demonstrating the superiority of a given approach. Historically, at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, we use RT before AHCT, with Rimner et al updating the data on 186 patients treated on salvage protocols between 1985 and 2008 who received accelerated involved field RT followed by total lymphoid irradiation (15-18 Gy) just before conditioning chemotherapy.7 The 5-year EFS and OS were 62% and 68%, and at 10 years were 56% and 56%, respectively, with 10 patients developing second malignancies. More focused fields can limit toxicity without a detriment to the outcome43 ; currently, we select patients with stage I or II disease to receive involved field RT or involved site RT. In addition, because there is also no randomized evidence supporting accelerated RT (ie, twice daily vs once daily), we generally recommend daily RT to mitigate toxicity if the patient is not on a clinical trial.

Alternatively, RT can also be given after AHCT.44 Consolidative RT was found to significantly improve the 2-year PFS (67% vs 42%, P < .01) without a significant change in OS (100% vs 93%, P = .015), with the most benefit seen in patients with traditional risk factors such as bulky disease, B-symptoms, primary refractory disease, and PR on pre-AHCT imaging.

Based on the fact that up to 50% of patients can relapse after AHCT, the AETHERA study randomized patients to maintenance therapy with 1.8 mg/kg BV every 3 weeks vs placebo.9 High-risk features for inclusion into the study were primary refractory disease, relapse within 1 year of initial therapy, and extranodal disease before salvage therapy. The most common adverse events in the BV arm were peripheral sensory neuropathy (56%) and neutropenia (35%). Updated results show a 3-year PFS rate of 61% for the BV arm vs 43% in the placebo arm, with an HR of 0.58 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.41-0.82).45 The 5 risk factors that predicted for worse PFS included initial remission duration <1 year, less than CR to most recent salvage therapy, extranodal disease at the time of salvage therapy, B-symptoms at the time of salvage therapy, and > 1 salvage required to show chemosensitive disease. The HRs for PFS with more than 1, 2, or 3 risk factors were 0.517, 0.412, and 0.382, respectively.46 QoL was measured by the European Quality of Life 5 dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire, which showed that BV-associated peripheral neuropathy did not have a large impact on QoL.47 Limitations of this study are partly due to design, given the availability of the drug when the trial started. No OS benefit was seen in this study, most likely because of the crossover between arms. In addition, patients in this study did not have BV before AHCT, and there are limited data for maintenance BV for those with pre-AHCT exposure. Both the BV-bendamustine and BV-ESHAP salvage trials allow for patients to resume BV maintenance after AHCT.32,34

Checkpoint inhibition is an attractive maintenance strategy because one can intervene in immune tolerance against changed tumor antigens, and the post-AHCT setting presents an ideal environment because of the gradual immune reconstitution with lymphocyte recovery. A multicenter study evaluating pembrolizumab as maintenance therapy after AHCT for HL is ongoing (NCT02362997).

Recommendation

BEAM remains our standard of care conditioning regimen. For patients whose salvage therapy did not include traditional chemotherapy, we recommend using CBV for the dose intensity. We incorporate involved site RT pre-AHCT for patients with early-stage disease whose disease would fit in a reasonably sized field. BV maintenance after HCT should be given to those patients with a higher likelihood of relapse, particularly those with more than 1 risk factor, regardless of prior BV exposure or remission status. However, maintenance therapy should be discontinued in patients who develop grade 2 or higher nonhematologic toxicities.

Relapse after AHCT

Before the development of new therapies, the median survival of HL patients relapsing after AHCT was 25 months.48 In recent years, 2 classes of agents have changed the landscape for patients with rrHL dramatically. BV was initially developed in this setting and FDA approved in 2011.49 In the phase 2 trial, 102 patients with relapse after AHCT received and CD30+ disease received 1.8 mg/kg by intravenous infusion every 3 weeks up to 16 cycles.50 CR was seen in 34% with an ORR of 74%; however, patients who did not achieve CR by first restaging were unlikely to achieve a CR with further therapy. With a median of 35-month follow-up, the estimated PFS and OS were 9.3 and 40.5 months, respectively.51 For the 34 patients who achieved CR, the 5-year PFS and OS were 52% and 64%, respectively, with lower disease burden, performance status, and younger age predictive of achieving a CR. The most common toxicities included peripheral sensory neuropathy, nausea, fatigue, neutropenia, and diarrhea. Although only 8 patients in this study proceeded to allo-HCT, Chen et al describe a slightly larger retrospective cohort of patients who proceeded to reduced intensity allo-HCT after BV and found the 1-year PFS and OS to be 92% and 100%, respectively, with 28% acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) and 56% chronic GVHD.52

More recently, modulation of the CPI pathways has yielded dramatic results in rrHL. PD-1 causes a transient downregulation of T-cell function after chronic antigen exposure, such as what occurs from the presence of HL. Blocking the inhibitory signal with monoclonal antibodies against PD-1, such as the fully human IgG4 nivolumab and the humanized IgG4-κ pembrolizumab, increases anti-HL activity and has led to the FDA approval of these agents because of improved outcomes. Similarly, monoclonal antibodies, including the humanized IgG1, atezolizumab, and fully human IgG1s, avelumab and durvalumab, have been developed against the ligand PD-L1, but remain under investigation.

In the HL cohort of the phase 1b Checkmate 039 study, the ORR was 87% with 17% CR and 70% PR. Although 18/23 patients had relapsed after AHCT and BV, responses occurred within 16 weeks of starting therapy in 75% and there was a 6-month PFS of 86%.53,54 Another cohort was treated with nivolumab + ipilimumab with a 74% ORR for HL, although CR rates were low.55 The subsequent multicenter phase 2 study (Checkmate 205) included only patients with HL relapsed after AHCT and BV and showed an ORR of 68% (13% CR, 55% PR) with nivolumab administered at 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks.56 With a minimum 23-month follow-up, the median PFS was 14.8 months, with 1-year PFS 54.6% and 1-year OS 94.9%.57 The median time to response was 2.1 months (interquartile ratio, 1.9-3) and median duration of response was 16 months (95% CI, 6.6-NR). Using the EQ-5D questionnaire and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire-Core 30, QoL improved over the course of nivolumab treatment, and similar to the phase 1 studies, high-grade AEs were infrequent, although grade 1-2 infusion reactions occurred in 20% of patients. IrAEs included pneumonitis and autoimmune hepatitis, each occurring in 1 patient.

The phase 1b Keynote-013 trial included classical HL patients who had progressed after BV and were treated with 10 mg/kg of pembrolizumab every 2 weeks until disease progression.58 IrAEs were seen in a portion of patients including grade 1-2 hypothyroidism in 16%, thyroiditis in 6%, and pneumonitis in 10%. The promising ORR of 73% in the 22/31 patients who had a prior AHCT and 65% overall led to the multicenter phase 2 study (Keynote-087). Because there was no exposure-response relationship, a flat dose of 200 mg once every 3 weeks was given for up to 24 months.59 ORR for all patients was 69%, with 22.4% CR and 47% PR. ORR response rate was 73.9% for those who progressed after AHCT and BV (n = 69), 64.2% for those ineligible for AHCT because chemoresistant disease after salvage chemotherapy and BV (n = 81), and 70% for those with progression but no BV after AHCT (n = 60, 41% exposed pre-AHCT). At 6 months, the PFS was 72.4% and OS 99.5%, with the median duration of response and OS not reached in all cohorts. Similarly to nivolumab, there was net improvement in the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire-Core 30 and EQ-5D QoL scores between baselines and week 12 of therapy. Grade 3 or higher AEs were again rare and included arthralgias, cough, diarrhea, dyspnea, fatigue, neutropenia, pyrexia, and vomiting. The most common irAE was low-grade hypothyroidism (13.8%).

In the phase 1 Avelumab In Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Stage Classical Hodgkin's Lymphoma trial (NCT02603419), avelumab is being evaluated in patients who are not eligible for transplant or whose disease has relapsed after either AHCT or allo-HCT.60 The ORR for all patients was 54.8%, with 2 CR (6.5%) and 15 PR (48.4%), including the 8 patients after allo-HCT, described in more detail later. In the preliminary results, 36.7% had grade 3 or higher treatment-related AEs.

Combinations of these agents with other novel or traditional chemotherapies are being studied in a multitude of ongoing trials.15 Furthermore, drugs targeting alternative pathways have yielded modest results. Histone deacetylase inhibitors, including mocetinostat, panobinostat, and vorinostat, have shown ORR between 4% to 59%, although with few CRs and some limiting toxicities,61-64 whereas the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mTOR pathway inhibited by everolimus alone or in combination yielded an ORR of 43% to 47%.65,66 The immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide has an ORR of 19% to 46%,67,68 whereas targeting the JAK/STAT pathway has yielded ORR of ∼60%, again with few CR.69,70 Other classes of medications are under investigation with varied response rates and toxicity profiles.13,14

Recommendation

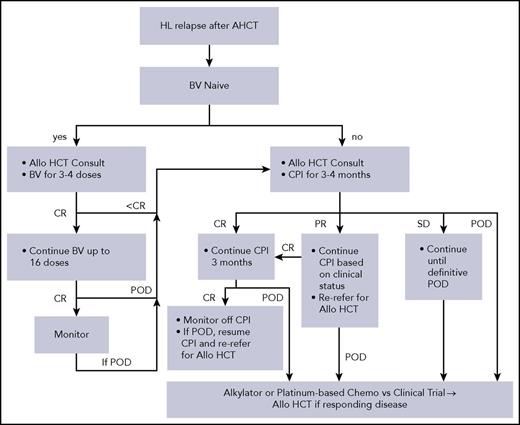

For patients who have not received BV in an earlier line of therapy, BV remains a highly active choice for first relapse after AHCT because there is a higher CR rate with BV than CPI. CPI is an effective option for the heavily pretreated with monitoring for irAEs. We believe patients should be referred for allo-HCT at the time of initiation of CPI. If they achieve a CR on CPI, we continue for 3 additional months. If the CR is maintained, we suggest stopping therapy, monitoring with the plan to restart if the patient progresses, and referring back for consideration of allo-HCT at that time. For PRs, we continue therapy based on clinical situation because patients can still convert to CR, but consider allo-HCT sooner. Finally, if there is stable disease on CPI, we continue therapy until definitive disease progression, but acknowledge that CR is unlikely to occur with further treatment. At progression, we recommend alkylator-based therapy with regimen choice based on previous treatments. We often use nitrogen mustard, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone chemotherapy vs a clinical trial as a bridge to allo-HCT for those with responding disease given that most patients have already received a standard salvage described previously (Figure 1).

Schema for relapse of HL after AHCT. Choice of chemotherapy is to be based on prior salvage regimens received. POD, progression of disease; SD, stable disease.

Schema for relapse of HL after AHCT. Choice of chemotherapy is to be based on prior salvage regimens received. POD, progression of disease; SD, stable disease.

Considerations for allo-HCT

Allo-HCT remains the therapeutic modality with the highest chance of cure for patients with multiple rrHL with the use of a donor immune system to prevent relapse. However, with the availability of newer agents, the timing and role of allo-HCT is less well defined. We focus our discussion on issues of importance related to allo-HCT after CPI because it is unlikely for a patient in 2018 to be transplanted without prior exposure to a BV and a CPI. Historical data regarding outcomes after allo-HCT have been reviewed extensively elsewhere.71

Early mouse models suggested the possibility of increased GVHD after prior CPI exposure because of the modulation of antigen-specific T-cell responses.72 Anecdotal clinical evidence of this led to a multicenter retrospective study of 39 patients (79% with HL), with a median of 62 days (range, 7-260) between allo-HCT and nivolumab (72%) or pembrolizumab (28%).73 Grade 2-4 aGVHD was seen in 44%, with the more severe grade 3-4 seen in 23%. Chronic GVHD occurred in 41% of patients by 1 year. Prolonged courses of steroids were needed to treat 7 patients for a noninfectious febrile syndrome shortly after allo-HCT. One patient died of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome and 3 from early aGVHD. One-year nonrelapse mortality was 11% (95% CI, 3-23), with 14% (95% CI, 4-29), 76% (95% CI, 56-87), and 89% (95% CI, 74-96) cumulative incidence of relapse, PFS, and OS, respectively. With a high PFS, allo-HCT remains feasible after CPI, but with need for monitoring of early immune side effects.

Similarly, Schoch et al found that prior CPI exposure (nivolumab or ipilimumab) did not alter the incidence or severity of GVHD for lymphoma patients who had received posttransplant cyclophosphamide for GVHD prophylaxis after haploidentical or matched donor allo-HCT.74 Eight of the 19 patients in this study had HL, and most (12/19) had received CPI >90 days before or >90 days after allo-HCT. Grade 2 aGVHD was seen in 4/11 patients with CPI before allo-HCT (3 with stage III skin involvement and 1 with stage III skin and stage I liver involvement). All patients had resolution of aGVHD with treatment and none developed cGVHD. Of the 9 patients with post–allo-HCT CPI, 1 developed grade 2 aGVHD with stage III cutaneous involvement after a donor lymphocyte infusion, but no other GVHD was seen.

Additional studies of CPI after allo-HCT show high response rates, with some increase in GVHD. A single-center retrospective analysis of 20 HL patients had an ORR of 95%, with 42% CR and 52% PR, and 6 patients remaining disease free after stopping nivolumab.75 There was a 30% incidence of acute GVHD, with 2 patients being steroid refractory, although all of these patients had prior aGVHD. GVHD caused 2 deaths, and the authors note that the timing of CPI may be a factor because patients who did not have prior GVHD did not develop GVHD after CPI. A multicenter retrospective analysis of 31 patients from 23 centers (94% with HL) who received nivolumab or pembrolizumab showed an ORR of 77% (15 CR and 8 PR).76 In this study, timing did not seem to relate to development of GVHD, but 8/10 deaths were caused by treatment emergent GVHD, 5 of which were hepatic. Overall, new-onset GVHD occurred in 55%, with 20% developing acute, 13% overlap, and 23% chronic GVHD after 1 to 2 doses. Nine of the 17 patients had grade 3 or higher GVHD and 14/17 required >2 therapies for GVHD. Finally, avelumab produced a 75% ORR in a phase 1 study with 8 patients, with 2 patients developing grade 3 liver GHVD, which resolved with treatment.60

An additional important consideration for allo-HCT is the availability of a donor. In recent years, several studies have evaluated or reviewed the use of haploidentical donors and found encouraging results.19,20,71,77,78 Most recently, the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation conducted a registry study of 709 patients (haploidentical, n = 98; matched sibling, n = 338; and matched unrelated donor, n = 273) and found no significant differences in PFS or OS between the donor types.20 Because these results expand donor possibilities, patient selection and modulation of transplant-related toxicities become paramount for good outcomes.

Recommendations

We suggest allo-HCT be considered for all patients with HL relapsed after AHCT or those ineligible for AHCT because of insufficient response or marrow-based disease. Patients should have responding disease before allo-HCT. Overall, CPI before or after allo-HCT is effective for disease control, with the risk of GVHD possibly modulated by increasing the time between CPI and allo-HCT if there is disease stability or with the use of additional GVHD prophylaxis such as posttransplant cyclophosphamide. The decision to proceed to allo-HCT should be individualized given the risks and potential benefits of transplant.

Conclusion

Over the past several years, significant and important advances have led to prolonged survival for patients with rrHL. Salvage therapy followed by AHCT remains the standard of care for cure in the second-line setting. As newer agents are incorporated earlier in the disease course, options for salvage and relapsed disease will need further study. Allo-HCT should be considered for patients with multiply relapsed disease, but the timing of transplant and mitigation of toxicities are important.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (P01 CA23766 and P30 CA008748).

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: G.L.S. and C.H.M. examined the available data and wrote the review.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.H.M. participates on the scientific advisory board and receives research funding from Seattle Genetics, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. G.L.S. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gunjan L. Shah, Adult Bone Marrow Transplant Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, Box 298, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: shahg@mskcc.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal