Key Points

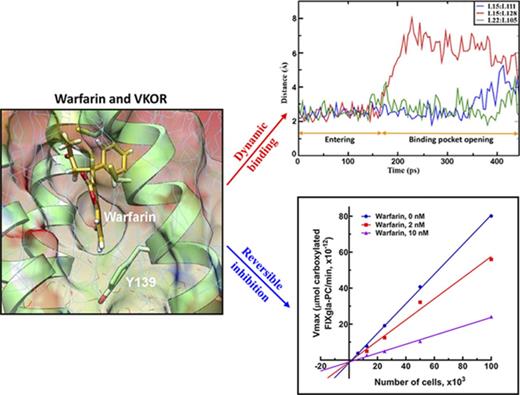

Warfarin reversibly inhibits VKOR by forming a T-shaped stacking interaction with residue Y139 of the proposed TYA warfarin-binding motif.

Warfarin-resistant nonbleeding phenotype for patients bearing VKOR mutations explained by MD simulation and cell-based functional study.

Abstract

Vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR), an endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein, is the key enzyme for vitamin K–dependent carboxylation, a posttranslational modification that is essential for the biological functions of coagulation factors. VKOR is the target of the most widely prescribed oral anticoagulant, warfarin. However, the topological structure of VKOR and the mechanism of warfarin’s inhibition of VKOR remain elusive. Additionally, it is not clear why warfarin-resistant VKOR mutations identified in patients significantly decrease warfarin’s binding affinity, but have only a minor effect on vitamin K binding. Here, we used immunofluorescence confocal imaging of VKOR in live mammalian cells and PEGylation of VKOR’s endogenous cytoplasmic-accessible cysteines in intact microsomes to probe the membrane topology of human VKOR. Our results show that the disputed loop sequence between the first and second transmembrane (TM) domain of VKOR is located in the cytoplasm, supporting a 3-TM topological structure of human VKOR. Using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a T-shaped stacking interaction between warfarin and tyrosine residue 139, within the proposed TY139A warfarin-binding motif, was observed. Furthermore, a reversible dynamic warfarin-binding pocket opening and conformational changes were observed when warfarin binds to VKOR. Several residues (Y25, A26, and Y139) were found essential for warfarin binding to VKOR by MD simulations, and these were confirmed by the functional study of VKOR and its mutants in their native milieu using a cell-based assay. Our findings provide new insights into the dynamics of the binding of warfarin to VKOR, as well as into warfarin’s mechanism of anticoagulation.

Introduction

Warfarin, a coumarin derivative, was originally used as a rodenticide in 1948. Due to its promise for preventing thromboembolic disorders, warfarin was approved as a medication in 1954, and has remained the mainstay of anticoagulation therapy.1,2 More than 30 million prescriptions for warfarin are written annually in the United States alone.3 Despite its effectiveness and widespread use, warfarin is also ranked among the top 10 medications with serious adverse drug events due to its narrow therapeutic index and the broad individual variability of dosing requirements.4 In the past decade, several novel oral anticoagulants that directly target thrombin and factor Xa have been advocated as warfarin replacements. However, the cost of these drugs, the challenges of reversing their anticoagulation effects, and the severe bleeding and ischemic stroke problems they can cause continue to make warfarin the choice of most physicians.5

Warfarin impairs the biosynthesis of functional vitamin K–dependent proteins by the inhibition of vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR). This action limits the production of carboxylated vitamin K–dependent proteins that control blood coagulation, vascular calcification, bone metabolism, and other important physiological processes.6 Site-direct mutagenesis studies show that cysteines 132 and 135 comprise a C132XXC135 active site redox center of VKOR.7,8 Based on multiple sequence alignments9 and functional studies of the naturally occurring warfarin-resistant mutations at residue Y139,10 the TY139A sequence has been proposed as part of the warfarin-binding site.9-11

VKOR is an integral endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane protein. Like other membrane proteins, structure-and-function studies of VKOR have been challenging, and the results of these studies are often controversial.12 Our current understanding of VKOR’s structure is based on biochemical studies of the membrane topology of human VKOR,13-15 on the x-ray crystal structure of a VKOR bacterial (Synechococcus) homolog (Syn-VKOR),16 and on computer-aided molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of human VKOR.17,18 Both 3- and 4-transmembrane (TM) topology models for human VKOR have been proposed. Although there is no doubt that the C132XXC135 redox motif is VKOR’s active site, the role of 2 other conserved cysteines (C43 and C51) remains controversial.14,16,19

The mechanism of how and where warfarin binds to VKOR is also unclear. Both irreversible20,21 and reversible22 inhibition mechanisms have been proposed for warfarin inhibition of VKOR. As a reversible inhibitor, warfarin appears to inhibit VKOR in a noncompetitive manner.23,24 However, a recent study suggests that warfarin competitively inhibits VKOR by competing with vitamin K.25 Several studies modeling warfarin’s action within model structures of VKOR have identified residues that potentially interact with warfarin.25,26 However, no direct interaction between warfarin and the experimentally supported TY139A warfarin-binding motif has been observed. It is worth noting that these modeling studies used a 4-TM topology model of human VKOR, derived from the crystal structure of Syn-VKOR, which appears to have a different topological structure from human VKOR.14 Therefore, the mechanism of warfarin inhibition of human VKOR at the molecular level remains elusive.

In this study, we reprobed the topological structure of human VKOR using immunofluorescence confocal imaging and a recently introduced approach for determining membrane protein topology.27,28 We also used a conventional all-atom MD simulation and a steered MD simulation to model the dynamic nature of warfarin binding to the 3-TM human VKOR structure. Results from the current study provide new insights into how warfarin binds to human VKOR within the context of the dynamics of the enzyme.

Methods

Materials and plasmid constructions

Mammalian dual expression vector pBudCE4.1, rabbit anti-human VKOR polyclonal antibody, AF-488–conjugated donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), and AF-568–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL). Mouse anti–protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) monoclonal antibody was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Mouse anti-tubulin monoclonal antibody was obtained from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). Mouse anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase monoclonal antibody was obtained from Proteintech Group, Inc (Rosemont, IL). mPEG-MAL-5000 was purchased from Laysan Bio Inc (Arab, AL). The QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit was obtained from Agilent (Santa Clara, CA). HEK293 and COS-7 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). HEK293 reporter cells with their endogenous VKOR and VKOR-like enzyme (VKORC1L1) knocked out by transcription activator-like effector nuclease–mediated genome editing were previously described.29 All VKOR mutations were created by a QuickChange Mutagenesis Kit in pBudCE4.1 mammalian expression vector, as previously described.14

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy and cytoplasmic-accessible cysteine PEGylation

To determine the location of the disputed loop sequence of VKOR in live cells, we used immunofluorescence confocal microscopy imaging, as previously described.30 In brief, human VKOR was transiently expressed in COS-7 cells on coverslips. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline solution and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were selectively permeabilized with either 50 μg/mL digitonin or 0.25% Triton X-100. Permeabilized cells were then blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin with 5% fetal bovine serum, and costained with primary antibodies. Primary antibody costaining includes rabbit anti-VKOR with mouse anti-tubulin (cytoplasmic marker) or with mouse anti-PDI (ER luminal marker) antibodies. Immunofluorescence staining was performed with AF-488–conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG and AF-568–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG. The cell nuclei were stained with 2 µM Hoechst 33342. Confocal microscopy was performed on a Zeiss LSM710 confocal laser-scanning microscope.31

For PEGylation of the endogenous cytoplasmic-accessible cysteine of VKOR, flag-tagged VKOR or its C43/51A mutant were stably expressed in HEK293 cells. VKOR containing microsomes were prepared and labeled by freshly prepared mPEG-MAL-5000, as previously described.27

Cell-based functional and enzyme kinetics study of VKOR

The cell-based functional study of VKOR and its mutants was performed in VKOR/VKORC1L1-knockout FIXgla-PC/HEK293 reporter cells, as previously described.29 VKOR activity was expressed as normalized carboxylated FIXgla-PC. Wild-type VKOR activity was normalized to 100%. Warfarin resistance was evaluated by determining the half-maximal inhibition concentration (IC50) of warfarin. To determine the reversibility of warfarin inhibition of VKOR, FIXgla-PC/HEK293 reporter cells were seeded with different numbers of cells in the multiwell cell-culture plate, and cultured with increasing concentrations of vitamin K epoxide (KO) in the presence and absence of warfarin. Apparent maximum velocity (Vmax) was determined by a Lineweaver-Burk plot. All data were processed using GraphPad software (La Jolla, CA).

Removal of warfarin from VKOR-warfarin complex

To study the reversibility of warfarin binding to VKOR in vitro, VKOR-containing microsomes7 (300 µL) were incubated with 30 µM warfarin on ice for 30 minutes. Then, warfarin was removed by diluting the VKOR-warfarin complex with Tris-HCl buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) containing 4% bovine serum albumin, and centrifuged at 45 000 rpm, 4°C for 1 hour.32 VKOR activity of the washed microsomes was determined, as previously described.7

MD simulations of warfarin binding to VKOR

MD simulations of warfarin binding to VKOR were performed as previously described.17 We outline simulations as 4 time-steps in this study (supplemental Figure 1 and supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site): step 1, providing an MD-equilibrated 3-TM VKOR in lipid and solvent; step 2, the 40-nanosecond equilibration of warfarin in the ER lumen near a reasonable access point to the interior of VKOR; step 3, steered MD simulation to move the warfarin molecule into the locality of the proposed warfarin-binding pocket; and step 4, the long (200 nanoseconds) MD simulations of 3 systems: wild-type VKOR, Y139A, and A26T mutants with warfarin initially located at the proposed warfarin-binding pocket at the final simulation of step 3. A separate calculation was started for VKOR at 80 nanoseconds, with equilibration following the removal of warfarin.

Results

Membrane topology of human VKOR

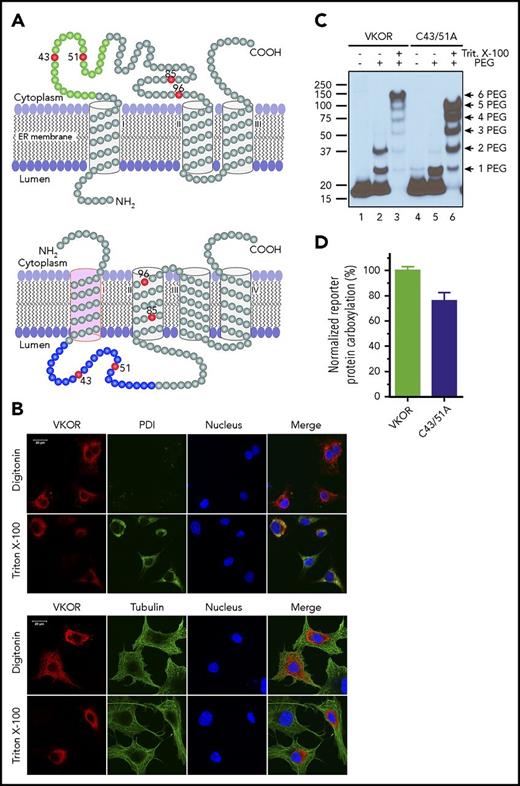

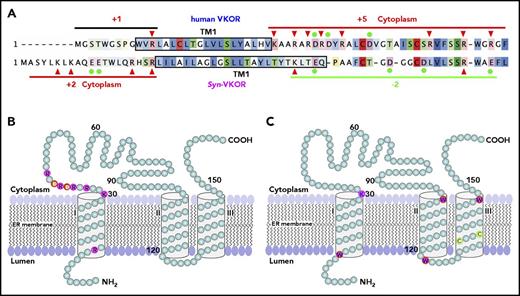

The current controversial 3- and 4-TM topology models of human VKOR have consistent orientations in their last 2 TMs. However, the first TM has opposite orientations that place the large loop sequence on different sides of the ER membrane (Figure 1A). Both models have been supported by VKOR topology studies using green fluorescence protein tagging.13,14 However, fusing a large protein tag to VKOR may perturb VKOR’s correct folding and/or membrane targeting. To probe the location of the disputed loop sequence of unmodified VKOR in live cells using immunofluorescence confocal imaging, we transiently expressed wild-type human VKOR in COS-7 cells and selectively permeabilized the cell membrane by digitonin so that the VKOR antibody could access only the cytoplasm, but not the ER lumen.14,30 Figure 1B (top panel) shows that VKOR is detected by the VKOR antibody (supplemental Note, “Validation of the VKOR antibody”) in the digitonin-permeabilized cells, suggesting the cytoplasmic location of the loop sequence; under the same conditions, the ER lumen marker PDI30 cannot be detected, indicating that the ER membrane is intact. When the ER membrane is permeabilized by Triton X-100, VKOR is perfectly colocalized with PDI. Probing VKOR and the cytoplasmic marker tubulin30 under similar permeabilization conditions (Figure 1B bottom panel) further confirmed the cytoplasmic location of the loop sequence. These results strongly suggest that the disputed loop sequence is located in the cytoplasm, which supports the 3-TM model of VKOR.

Membrane topology of human VKOR. (A) The proposed 3-TM (based on Tie et al15 ) and 4-TM (based on Li et al16 ) topology models of human VKOR. Cysteine residues (C43, C51, C85, and C96) in the disputed loop sequence are marked in red. Cysteine residues (C16, C132, and C135) located within the TM helices are not shown. The loop sequence (A34-W59) specifically recognized by a VKOR antibody is marked green in the 3-TM model and blue in the 4-TM model. (B) Localization of the disputed loop sequence of human VKOR by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy in live mammalian cells. COS-7 cells expressing wild-type human VKOR were either selectively or fully permeabilized with digitonin or Triton X-100, respectively. Cytoplasmic proteins are accessible to antibody staining after selective permeabilization with digitonin, whereas ER lumen proteins are accessible for staining after full permeabilization with Triton X-100. Cells were coimmunostained with anti-VKOR (red) and anti-PDI (green) antibodies (top panel) or with anti-VKOR (red) and anti-tubulin (green) antibodies (bottom panel). The cell nucleus was stained by Hoechst 33342 (blue). (C) PEGylation of the cytoplasmic-accessible cysteines of VKOR with a membrane-impermeable maleimide polyethylene glycol (mPEG-MAL-5000). C-terminal FLAG-tagged VKOR or its C43/51A mutant was stably expressed in HEK293 cells. Intact microsomes were prepared and labeled with mPEG-MAL-5000 with/without Triton X-100 permeabilization. VKOR bands were visualized by western blot analysis. (D) Cell-based activity assay of VKOR and its C43/51A mutant. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3).

Membrane topology of human VKOR. (A) The proposed 3-TM (based on Tie et al15 ) and 4-TM (based on Li et al16 ) topology models of human VKOR. Cysteine residues (C43, C51, C85, and C96) in the disputed loop sequence are marked in red. Cysteine residues (C16, C132, and C135) located within the TM helices are not shown. The loop sequence (A34-W59) specifically recognized by a VKOR antibody is marked green in the 3-TM model and blue in the 4-TM model. (B) Localization of the disputed loop sequence of human VKOR by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy in live mammalian cells. COS-7 cells expressing wild-type human VKOR were either selectively or fully permeabilized with digitonin or Triton X-100, respectively. Cytoplasmic proteins are accessible to antibody staining after selective permeabilization with digitonin, whereas ER lumen proteins are accessible for staining after full permeabilization with Triton X-100. Cells were coimmunostained with anti-VKOR (red) and anti-PDI (green) antibodies (top panel) or with anti-VKOR (red) and anti-tubulin (green) antibodies (bottom panel). The cell nucleus was stained by Hoechst 33342 (blue). (C) PEGylation of the cytoplasmic-accessible cysteines of VKOR with a membrane-impermeable maleimide polyethylene glycol (mPEG-MAL-5000). C-terminal FLAG-tagged VKOR or its C43/51A mutant was stably expressed in HEK293 cells. Intact microsomes were prepared and labeled with mPEG-MAL-5000 with/without Triton X-100 permeabilization. VKOR bands were visualized by western blot analysis. (D) Cell-based activity assay of VKOR and its C43/51A mutant. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3).

The 3-TM VKOR is further supported by PEGylation of VKOR’s endogenous cytoplasmic-accessible cysteines with a membrane-impermeable thiol-reactive reagent, mPEG-5000.27 Figure 1C shows that 2 PEGylated VKOR bands are clearly observed (lane 2), suggesting the cytoplasmic location of VKOR’s loop cysteines. This is further confirmed by mutating C43 and C51 (retaining ∼80% activity, Figure 1D), which significantly decreased the 2-PEG VKOR adduct (Figure 1C lane 5). These results, consistent with our previous results,14 again support the 3-TM model of VKOR. Additionally, VKOR with both C43 and C51 mutated to alanine retains ∼80% activity, suggesting that these 2 cysteines are not required for VKOR’s active site regeneration.

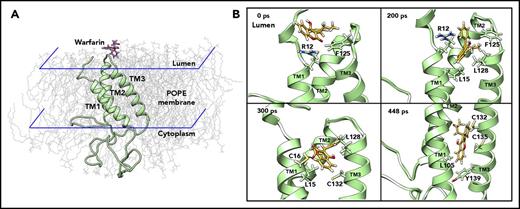

MD simulation of warfarin accessing its binding site in VKOR

Based on the significant experimental data and our MD-simulation results comparing the 3- and 4-TM models of VKOR,17 we performed the MD simulation of warfarin binding to the 3-TM VKOR with a reduced active site (supplemental Note, “Modeling warfarin binding to active site reduced VKOR”) via the ER lumen (supplemental Note, “Modeling warfarin binding to VKOR via cytoplasm”). We first performed unconstrained conventional MD simulation for 40 nanoseconds to equilibrate the initial configuration of VKOR with warfarin near the luminal face of a path that would enable warfarin to locate the proposed TY139A-binding motif (Figure 2A). We then used steered MD simulation33,34 to enable warfarin, accessing its binding site within a reasonable time (448 picoseconds) (supplemental Video). Warfarin encounters several key residues along the path from the entrance to the putative binding pocket (Figure 2B). Residues R12 and F125 initially resist warfarin’s access to the inside of VKOR. Then, it encounters L15 and L128, which are essential for holding TM1 and TM3 together to maintain a stable VKOR structure.17 At the final stage, the side chain of warfarin is placed near the 2 active site cysteines, and the coumarin moiety located near L105, 1 of the hydrophobic residues that helps hold TM1 and TM2 together by hydrophobic interaction with L22.17 Importantly, warfarin, by this path, is located near the proposed TY139A-binding motif forming a T-shaped π-π stacking interaction with residue Y139 (supplemental Figure 2A).

MD simulation of warfarin binding to VKOR. (A) The initial position of warfarin and the 3-TM VKOR in 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (POPE) lipid bilayer in the ionic water environment. For clarity, water molecules and ions are not shown. Warfarin was added to the ER lumen of VKOR (structure of the last snapshot of the 62-nanosecond simulation according to Wu et al17 ), and equilibrated for 40 nanoseconds using unconstrained conventional MD simulation. (B) Snapshots of the steered MD simulation of warfarin accessing the putative binding site of VKOR during 448 picoseconds. For clarity, water, ions, and lipids molecules are not shown. Key residues, encountered during warfarin accessing the binding site in VKOR, are labeled and displayed using stick diagrams.

MD simulation of warfarin binding to VKOR. (A) The initial position of warfarin and the 3-TM VKOR in 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (POPE) lipid bilayer in the ionic water environment. For clarity, water molecules and ions are not shown. Warfarin was added to the ER lumen of VKOR (structure of the last snapshot of the 62-nanosecond simulation according to Wu et al17 ), and equilibrated for 40 nanoseconds using unconstrained conventional MD simulation. (B) Snapshots of the steered MD simulation of warfarin accessing the putative binding site of VKOR during 448 picoseconds. For clarity, water, ions, and lipids molecules are not shown. Key residues, encountered during warfarin accessing the binding site in VKOR, are labeled and displayed using stick diagrams.

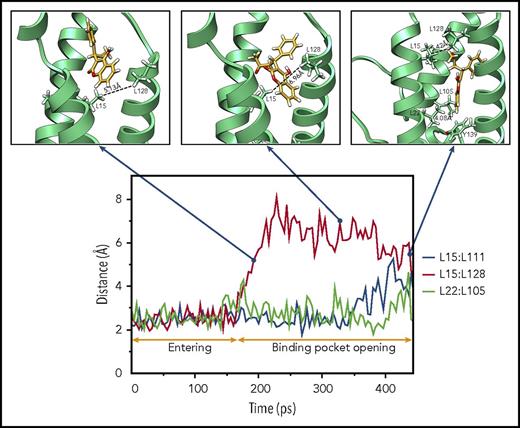

Dynamic binding pocket opening when warfarin binds to VKOR

As warfarin accesses its binding site, it encounters several hydrophobic residues that are essential for maintaining VKOR’s stable structure. We assume that the interactions between these hydrophobic residues must be weakened to allow warfarin to access its binding pocket. To test this hypothesis, we recorded the minimum distance between the paired leucine residues17 during the 448-picosecond steered MD simulation. Our results show a dramatic increase in the minimum distance between L15 and L128 at ∼160 picoseconds (Figure 3), suggesting the opening of the warfarin-binding pocket in VKOR. Thereafter, warfarin appears to penetrate into the new cavity of VKOR, as evidenced by significant increases in the minimum distances between L15 and L111 (at 400 picoseconds) and L22 and L105 (at 440 picoseconds). At the same time, the minimum distance between L15 and L128 significantly decreases, suggesting the restoration of the opened entrance. This ordered increase and decrease of the minimum distances between the paired leucine residues provides us with a sequential dynamic opening and closing of the warfarin-binding pocket when warfarin binds VKOR.

Sequential binding pocket opening when warfarin accesses its binding site. The profile of the minimum distances between the hydrophobic paired leucine residues (L15:L111, L15:L128, and L22:L105) that help sustain a stable VKOR structure are recorded during the 448-picosecond steered MD simulation (bottom). Snapshots of warfarin inside VKOR at the indicated time points are shown (insets). Key residues, encountered during warfarin’s accessing the binding site in VKOR, are labeled and displayed using stick diagrams. Minimum distances between paired lysine residues are labeled.

Sequential binding pocket opening when warfarin accesses its binding site. The profile of the minimum distances between the hydrophobic paired leucine residues (L15:L111, L15:L128, and L22:L105) that help sustain a stable VKOR structure are recorded during the 448-picosecond steered MD simulation (bottom). Snapshots of warfarin inside VKOR at the indicated time points are shown (insets). Key residues, encountered during warfarin’s accessing the binding site in VKOR, are labeled and displayed using stick diagrams. Minimum distances between paired lysine residues are labeled.

The phenyl ring of Y139 is essential for stabilizing warfarin binding

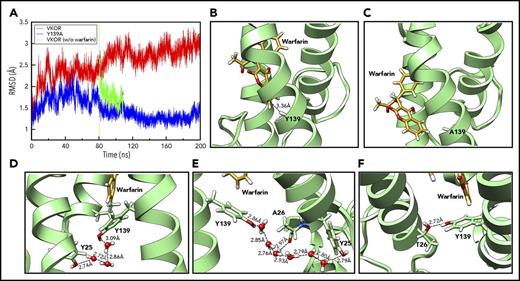

To investigate the role of Y139 in warfarin binding, we performed 200-nanosecond unconstrained conventional MD simulation for warfarin binding to VKOR and its Y139A mutant, which has the aromatic ring of Y139 removed. Compared with VKOR, the Y139A mutant shows significantly lower backbone root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values during the 200-nanosecond simulation (Figure 4A), suggesting a less distorted architecture. From ∼80 nanoseconds, the RMSD value of VKOR significantly increases, indicating that VKOR is undergoing a structural distortion as it equilibrates with warfarin. However, the backbone RMSD value for the Y139A mutant decreases prominently after 80 nanoseconds, eventually annealing to the value of the reference structure. This result suggests that warfarin rapidly escapes from the Y139A mutant, and that the distortion to VKOR structure is reversible. The reversibility of the VKOR structure deformation was further confirmed by the removal of warfarin from the wild-type VKOR simulation at 80 nanoseconds, showing that the RMSD for the warfarin-less VKOR structure rapidly relaxed in the direction of the reference structure. Warfarin retains its T-shaped stacking interaction with Y139 in the wild-type VKOR (Figure 4B), however, it loses the interaction and escapes from the binding pocket in the Y139A mutant (Figure 4C). The free phenyl ring of warfarin is positioned outside of VKOR’s TM helices and forms hydrophobic interactions with a lipid molecule in the environment (supplemental Figure 2B). These results strongly suggest that the aromatic ring of residue Y139, which enables the complex T-shaped stacking interactions, is the critical moiety for warfarin binding. Surface representations of the warfarin-binding pockets of VKOR and the Y139A mutant with warfarin are shown in supplemental Figure 3.

Unconstrained MD simulation of warfarin binding to VKOR, Y139A, and A26T mutants. (A) The backbone RMSD profiles of VKOR (red) and the Y139A mutant (blue) during the 200-nanosecond unconstrained MD simulation. The green curve shows the backbone RMSD profile of wild-type VKOR when warfarin is removed at the 80-nanosecond time point and the structure is reequilibrated before additional simulation. (B) Warfarin binding to wild-type VKOR at the last snapshot of the 200-nanosecond unconstrained MD simulation. A T-shaped π-π stacking interaction between warfarin and Y139 is shown (nearest carbon-carbon distance of 3.36 Å). (C) Warfarin binding to the Y139A mutant at the last snapshot of the 200-nanosecond unconstrained MD simulation. Warfarin drifts away from its initial site. (D) Configuration of Y25, Y139, and warfarin at the last snapshot of the 448-picosecond steered MD simulation. Y25 stabilizes Y139 by forming a hydrogen bond network via water molecules from the environment. (E) Warfarin-binding pocket at the 24-nanosecond snapshot of the unconstrained conventional MD simulation. Y139 was stabilized by forming a new hydrogen bond network via water molecules with the backbone of A26. (F) Configuration of the warfarin-binding pocket of the A26T mutant at the 200-nanosecond snapshot of the unconstrained conventional MD simulation. Y139 was stabilized by directly forming a hydrogen bond with A26T.

Unconstrained MD simulation of warfarin binding to VKOR, Y139A, and A26T mutants. (A) The backbone RMSD profiles of VKOR (red) and the Y139A mutant (blue) during the 200-nanosecond unconstrained MD simulation. The green curve shows the backbone RMSD profile of wild-type VKOR when warfarin is removed at the 80-nanosecond time point and the structure is reequilibrated before additional simulation. (B) Warfarin binding to wild-type VKOR at the last snapshot of the 200-nanosecond unconstrained MD simulation. A T-shaped π-π stacking interaction between warfarin and Y139 is shown (nearest carbon-carbon distance of 3.36 Å). (C) Warfarin binding to the Y139A mutant at the last snapshot of the 200-nanosecond unconstrained MD simulation. Warfarin drifts away from its initial site. (D) Configuration of Y25, Y139, and warfarin at the last snapshot of the 448-picosecond steered MD simulation. Y25 stabilizes Y139 by forming a hydrogen bond network via water molecules from the environment. (E) Warfarin-binding pocket at the 24-nanosecond snapshot of the unconstrained conventional MD simulation. Y139 was stabilized by forming a new hydrogen bond network via water molecules with the backbone of A26. (F) Configuration of the warfarin-binding pocket of the A26T mutant at the 200-nanosecond snapshot of the unconstrained conventional MD simulation. Y139 was stabilized by directly forming a hydrogen bond with A26T.

Y25 and A26 interact with Y139 to stabilize warfarin binding in VKOR

When warfarin binds to VKOR, we initially observed that Y139 interacts with Y25 through water molecules from the environment via a hydrogen-bond network (Figure 4D). After 24-nanosecond unconstrained conventional MD simulation, the relative configurations of Y25, Y139, and warfarin are somewhat changed: TM1 has rotated counterclockwise, causing Y25 to move apart from Y139 and A26 to face toward Y139. A new hydrogen-bond network is observed in which Y139 interacts with both Y25 and A26 (backbone) via water molecules (Figure 4E); this network stabilizes warfarin binding to VKOR. To explore the contribution of A26 to warfarin binding, we performed the same MD simulation for the naturally occurring warfarin-resistant A26T mutant35 in the presence of warfarin as we did for the Y139A mutant. Unexpectedly, the RMSD value for the A26T mutant increases to 2.5 Å at ∼60 nanoseconds and then gradually moves toward the value of wild-type VKOR (supplemental Figure 4). The RMSD value of A26T stabilizes similarly to that of the wild-type simulation beyond 200 nanoseconds (data not shown). This stability is apparently enabled by the formation of a direct hydrogen-bond between the hydroxyl groups of A26T and Y139, which stabilizes the warfarin-binding pocket (Figure 4F). This result suggests that the naturally occurring warfarin-resistant A26T mutant should have a similar warfarin sensitivity as wild-type VKOR.

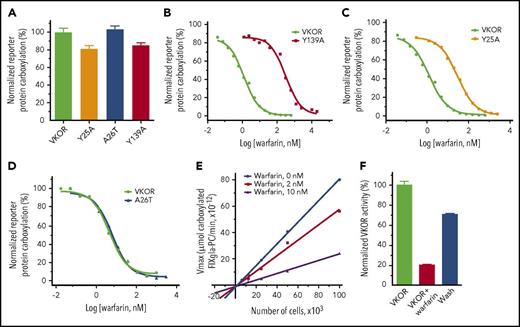

Validation of the identified warfarin-binding residues in physiological conditions

To experimentally evaluate our MD-simulation results in physiological conditions, we mutated each of the identified residues critical to warfarin binding, as we did in the MD simulation. We then examined the warfarin-binding affinity of these mutants in a cellular environment.29 Figure 5A shows that mutating these residues (Y25, A26 and Y139) has only a minor effect on VKOR activity. However, warfarin resistance of the Y139A mutant increases 284-fold (Figure 5B; supplemental Table 2), suggesting that the warfarin-binding affinity is significantly reduced. This result is consistent with our MD simulation result, which shows that the Y139A mutant has significantly lower RMSD values and that warfarin eventually escapes from the binding pocket (Figure 4A,C). Additionally, the warfarin resistance of the Y25A mutant increased 24.3-fold (Figure 5C), which agrees with a recent finding that the Y25 mutation is the causative mutation in the warfarin-resistant rat.36 Nevertheless, mutating Y25 has a significantly lessened effect on warfarin resistance than mutating Y139 (24.3-fold vs 284-fold), suggesting that Y25 contributes less to warfarin binding than Y139. This, again, agrees with our MD-simulation results, which indicate that Y25 does not directly interact with warfarin, but instead stabilizes the initial structure of VKOR by interacting with Y139 (Figure 4D).

Functional study of VKOR and its mutants. (A) Cell-based activity assay of VKOR and its mutants. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Warfarin-resistance study of the Y139A mutant (B), the Y25A mutant (C), and the A26T mutant (D) were performed by culturing the VKOR/VKORC1L1-knockout FIXgla-PC/HEK293 reporter cells expressing the individual mutant with 5 µM KO containing increasing concentrations of warfarin. Warfarin resistance, as determined by IC50, is available in supplemental Table 2. (E) The response of apparent Vmax to VKOR concentrations in the presence and absence of warfarin. Apparent Vmax was determined under different enzyme concentrations, with 0 nM, 2 nM, and 10 nM warfarin. VKOR concentrations were controlled by seeding different numbers of the reporter cells into the multiwell cell culture plate. Because the reporter cell line was derived from a single cell colony, we assume that each individual cell has a similar expression level of the endogenous VKOR, and VKOR concentration is proportional to the cell numbers. (F) Removal of warfarin from the VKOR-warfarin complex. VKOR-containing microsomes were incubated with 30 µM warfarin on ice for 30 minutes; warfarin was then removed by dilution and ultracentrifugation for activity assay. VKOR, VKOR-containing microsomes; VKOR+warfarin, VKOR-containing microsomes incubated with 30 µM warfarin; Wash, warfarin-treated VKOR-containing microsomes after wash.

Functional study of VKOR and its mutants. (A) Cell-based activity assay of VKOR and its mutants. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Warfarin-resistance study of the Y139A mutant (B), the Y25A mutant (C), and the A26T mutant (D) were performed by culturing the VKOR/VKORC1L1-knockout FIXgla-PC/HEK293 reporter cells expressing the individual mutant with 5 µM KO containing increasing concentrations of warfarin. Warfarin resistance, as determined by IC50, is available in supplemental Table 2. (E) The response of apparent Vmax to VKOR concentrations in the presence and absence of warfarin. Apparent Vmax was determined under different enzyme concentrations, with 0 nM, 2 nM, and 10 nM warfarin. VKOR concentrations were controlled by seeding different numbers of the reporter cells into the multiwell cell culture plate. Because the reporter cell line was derived from a single cell colony, we assume that each individual cell has a similar expression level of the endogenous VKOR, and VKOR concentration is proportional to the cell numbers. (F) Removal of warfarin from the VKOR-warfarin complex. VKOR-containing microsomes were incubated with 30 µM warfarin on ice for 30 minutes; warfarin was then removed by dilution and ultracentrifugation for activity assay. VKOR, VKOR-containing microsomes; VKOR+warfarin, VKOR-containing microsomes incubated with 30 µM warfarin; Wash, warfarin-treated VKOR-containing microsomes after wash.

The A26T mutation has been identified as a warfarin-resistant mutation in a patient who requires a high dose of phenprocoumon (4-hydroxycoumarin derivative similar to warfarin) to reach the desired anticoagulation effect.35 However, our cell-based warfarin resistance results show that the A26T mutant has similar warfarin sensitivity as wild-type VKOR (Figure 5D). This result is again consistent with our MD simulation result in that the A26T mutant, with its warfarin-binding site stabilized by forming a hydrogen-bond between A26T and Y139 (Figure 4F), has a similar RMSD profile as VKOR (supplemental Figure 4). Therefore, the A26T mutation appears not to be the causative mutation for the warfarin-resistant phenotype of the reported patient.

Warfarin is a reversible inhibitor of VKOR

Our MD-simulation results show that much of the distortion to VKOR’s structure caused by warfarin binding can be restored instantaneously by removing warfarin from the VKOR/warfarin complex (Figure 4A). Likewise, the action of warfarin binding to the Y139A mutant appears to also support a reversible inhibition mechanism (Figure 4C). This agrees with the notion that warfarin is a reversible inhibitor of VKOR.23,24,37 However, an irreversible inhibition mechanism has also previously been proposed for warfarin’s inhibition of VKOR.20,21 To distinguish warfarin’s inhibition mechanism, we examined the effect of warfarin on the apparent Vmax of VKOR at different VKOR concentrations using our cell-based assay (VKOR concentrations were controlled by seeding different cell numbers in the cell culture plate as described in “Methods”).38 The plotted lines of apparent Vmax vs VKOR concentrations in the presence of warfarin have smaller slopes than the control line (without warfarin) (Figure 5E); all lines meet near the origin. This result suggests that warfarin’s inhibition of VKOR is a reversible inhibition39 (supplemental Note, “Distinguish between reversible and irreversible inhibitions”). This reversible inhibition mechanism is further confirmed by the removal of warfarin from the warfarin/VKOR complex, as in the MD simulation. More than 70% of warfarin-inactivated VKOR activity can be restored by washing off the warfarin-inactivated VKOR-containing microsomes (Figure 5F). Together, these results suggest that warfarin is a reversible inhibitor of VKOR, a finding that is consistent with our MD-simulation results.

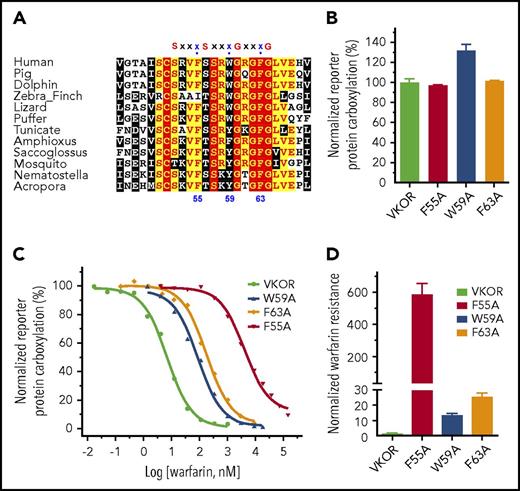

Proposed warfarin-binding residues and vitamin K–binding site in VKOR

Mutations of several residues in VKOR result in warfarin resistance. These residues are proposed as warfarin-binding residues and their locations are assumed to be close to or within the vitamin K–binding site.16,25,35,40 It has been proposed that warfarin and vitamin K compete to bind to residue F55.25 Residue F55 is located within a conserved region with several successive “small-XXX-small” motifs (the 2 small residues typically are glycine, but could also be alanine or serine) (Figure 6A), which is important for promoting membrane protein helix-helix interaction and membrane protein folding.41,42 The third residues of the XXX sequences in these motifs are conserved aromatic residues, including F55, W59, and F63. These aromatic residues are located approximately on the same face of an α-helix of the peptide. To explore the possible role of these aromatic residues in VKOR, we mutated each of these residues to alanine and examined their effect on warfarin and vitamin K binding. Figure 6B shows that mutating these residues has only a minor effect on VKOR activity (vitamin K binding). However, these mutations dramatically decrease VKOR’s warfarin-binding affinity; warfarin sensitivity of these mutants decreased from ∼13-fold to ∼600-fold compared with that of the wild-type enzyme (Figure 6C-D). These results suggest that the “small-XXX-small” sequences in VKOR significantly contribute to warfarin binding, but not to vitamin K binding. It also suggests that the proposed warfarin-binding residues in VKOR do not necessarily comprise the vitamin K–binding site.

Functional study of the aromatic residues in the small-XXX-small motifs of the loop sequence in VKOR. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of VKOR near the small-XXX-small motifs of the loop sequence. Amino acid sequences of VKOR from widely divergent species were aligned by CLUSTAL W. Conserved aromatic residues are indicated by numbers according to the position of amino acid residues in the human VKOR sequence. (B) Cell-based activity assay of the aromatic residue mutants of VKOR. (C) Warfarin-resistance study of the aromatic residue mutants of VKOR, performed as described in the legend for Figure 5. (D) Normalized warfarin resistance of the aromatic residue mutants of VKOR. Warfarin sensitivity of wild-type VKOR was normalized to 1. Warfarin resistance, as determined by IC50, is available in supplemental Table 2.

Functional study of the aromatic residues in the small-XXX-small motifs of the loop sequence in VKOR. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of VKOR near the small-XXX-small motifs of the loop sequence. Amino acid sequences of VKOR from widely divergent species were aligned by CLUSTAL W. Conserved aromatic residues are indicated by numbers according to the position of amino acid residues in the human VKOR sequence. (B) Cell-based activity assay of the aromatic residue mutants of VKOR. (C) Warfarin-resistance study of the aromatic residue mutants of VKOR, performed as described in the legend for Figure 5. (D) Normalized warfarin resistance of the aromatic residue mutants of VKOR. Warfarin sensitivity of wild-type VKOR was normalized to 1. Warfarin resistance, as determined by IC50, is available in supplemental Table 2.

Discussion

VKOR is the target of warfarin, the most widely used oral anticoagulant. Genetic variations in VKOR significantly affect warfarin’s clinical dosages, making it difficult to achieve the desired anticoagulation effect.43 About 30 missense mutations in the VKOR gene have been identified in patients requiring high doses of warfarin to reach the desired anticoagulation (supplemental Table 3). These mutations are referred to as warfarin-resistant mutations. However, it is not clear why most of these mutations significantly decrease the affinity of warfarin binding, but do not affect vitamin K binding.29,40 Therefore, a detailed structure-guided understanding of how warfarin targets VKOR in its native milieu is not only essential for clarifying the mechanism of action, but also provides important clues into warfarin dosage management and the possible development of new anticoagulant drugs.

The binding of a substrate or inhibitor to an enzyme is a dynamic process that often alters the enzyme’s structure.44,45 To better understand the dynamic structural details of VKOR upon warfarin binding, we used MD simulation, a powerful tool for studying protein dynamics,46 to explore the process of warfarin binding to VKOR. Our results show that the hydrophobic interactions between the TM helices that stabilize VKOR’s structure are sequentially weakened to allow warfarin to access its bindings site (Figure 3). When warfarin reaches its binding pocket, it forms a stabilized interaction with Y139 through the complex T-shaped π-π stacking interaction. This interaction is further confirmed by unconstrained MD simulations (Figure 4) and by cell-based functional studies of the Y139A mutant (Figure 5).

The T-shaped stacking configuration between warfarin and Y139 can happen only in the 3-TM model of VKOR, not the 4-TM model.16,47 In the 3-TM model, residue Y139 and the C132XXC135 active site motif, together with the 3 TM helices, form a hydrophobic-binding pocket (supplemental Figure 3). This pocket is consistent with the hydrophobic characteristics of the enzyme’s substrate/inhibitor. Additionally, in the 3-TM model, the distribution of the charged residue flanking TM1 agrees with the “positive-inside rule”48-51 (Figure 7A-B), a dominant factor that affects the orientation of a given TM helix of membrane proteins. Furthermore, 4 tryptophan residues and 1 cytoplasmic lysine residue are located at the membrane’s bilayer interface of the 3-TM model of VKOR (Figure 7C), serving as anchoring residues to fix the TM helix within the lipid bilayer.52-55 These membrane interfacial residues play an important role in controlling the membrane protein’s stability and function.56 Of the 6 membrane interfaces, only the N terminus of TM3, near the enzyme’s active site, does not have a characteristic interface-defining residue. This could be related to this local sequence being involved in the substrate binding and/or product releasing.

Membrane protein topology determinants and the proposed 3-TM membrane topology for human VKOR. (A) Charged residue distribution flanking TM1 of human VKOR and Syn-VKOR. Positively charged residues are indicated by red arrowheads and negatively charged residues are indicated by filled green circles. Net charges flanking TM1 of both proteins are indicated. Boxed sequences represent the proposed TM1 according to Tie et al15 and Li et al16 . Sequence alignment was adapted from Li et al16 . (B) Distribution of charged residues flanking TM1 in the proposed 3-TM structure of human VKOR. Positively and negatively charged residues are highlighted and labeled with single letter amino acid abbreviations. (C) Distribution of the membrane interfacial anchors in the proposed 3-TM structure of human VKOR. Membrane interfacial residues and active site cysteine residues are highlighted and labeled with single letter amino acid abbreviations.

Membrane protein topology determinants and the proposed 3-TM membrane topology for human VKOR. (A) Charged residue distribution flanking TM1 of human VKOR and Syn-VKOR. Positively charged residues are indicated by red arrowheads and negatively charged residues are indicated by filled green circles. Net charges flanking TM1 of both proteins are indicated. Boxed sequences represent the proposed TM1 according to Tie et al15 and Li et al16 . Sequence alignment was adapted from Li et al16 . (B) Distribution of charged residues flanking TM1 in the proposed 3-TM structure of human VKOR. Positively and negatively charged residues are highlighted and labeled with single letter amino acid abbreviations. (C) Distribution of the membrane interfacial anchors in the proposed 3-TM structure of human VKOR. Membrane interfacial residues and active site cysteine residues are highlighted and labeled with single letter amino acid abbreviations.

All of these defining features, however, appear to be inconsistent with the 4-TM model of human VKOR derived from the structure of Syn-VKOR (supplemental Note, “The differences between human VKOR and its bacterial homolog”). The orientation of TM1 in the 4-TM model is especially at odds with the “positive-inside rule.” However, the orientation of TM1 of Syn-VKOR in the 4-TM structure agrees with the “positive-inside rule” (Figure 7A). In general, the 3-TM model for human VKOR and the 4-TM model for Syn-VKOR appear to fit most of the membrane protein topology determinants. The controversy concerning the membrane topology of human VKOR basically arises from the direct application of the human VKOR sequence to the 4-TM Syn-VKOR topological structure.

Our MD-simulation results show that when warfarin binds to VKOR, it causes a modest reversible distortion of VKOR’s architecture but does not disrupt the overall 3-TM structure. This observed conformational change of VKOR’s architecture involves a large number of residues; mutating any of these residues could affect warfarin binding without affecting vitamin K binding. As we observed, mutating residues Y25, F55, W59, F63, and Y139 significantly increased warfarin resistance, but only had a minor effect on VKOR activity (Figures 5 and 6). Additionally, residue L128, like Y139, appears to be another “hot spot” for the naturally occurring warfarin-resistant mutations (supplemental Table 3). Mutating L128 significantly increased warfarin resistance (∼30-fold) but did not affect VKOR activity.29,40 This again is consistent with our MD simulation results showing that L128 interacts with L15 to stabilize VKOR’s structure, and controls the opening and closing of the putative warfarin-binding pocket (Figure 3). Therefore, our model successfully explains why most of the warfarin-resistant mutants have normal VKOR activity, which agrees with the nonbleeding phenotypes of patients carrying these mutations.

Our results from both the MD simulation and the cell-based activity assay study suggest that the naturally occurring A26T mutation is not the causative mutation for the warfarin-resistant phenotype. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that not all warfarin-resistant VKOR mutations identified in patients are associated with warfarin-resistant VKOR activity.29,37 It suggests that factors other than VKOR could play important roles in the warfarin-resistant phenotype. For example, in addition to clinical variables, genetic variation of cytochrome P450 2C9 (a warfarin metabolism enzyme, has also been strongly associated with warfarin-resistant phenotype.57 The general consistency of our MD-simulation results, along with the cell-based experimental data, not only help us to understand the mechanism of warfarin inhibition of VKOR, but also provide important clues to help explain warfarin-resistant clinical phenotypes and design safer anticoagulant drugs for treating disorders involving vitamin K metabolism.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Y. Shim for technical assistance on the parameterization of warfarin.

This work was supported by grant HL131690 from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (J.-K.T. and D.W.S.), and the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (2015R1D1A1A01061125/NRF-2017M3D1A) (S.W.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.W., D.W.S., J.-K.T., and L.G.P. conceived the studies; S.W. performed MD simulation and analyzed the data; X.C. and D.-Y.J. performed cell-based VKOR function studies and analyzed the data; X.C. performed enzyme kinetics study and VKOR endogenous cysteine PEGylation; J.-K.T. performed the immunofluorescence confocal microscopy study; and S.W., J.-K.T., and L.G.P. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lee G. Pedersen, Department of Chemistry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; e-mail: pedersen@ad.unc.edu; or Jian-Ke Tie, Department of Biology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; e-mail: jktie@email.unc.edu.

REFERENCES

Author notes

S.W. and X.C. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal