Introduction Patients with secondary acute myeloid leukemia (sAML) after myelodysplastic (MDS) or myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) treated with chemotherapy show poorer outcomes compared with de novo AML; consequently, these cases should be allocated to allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT) whenever possible (Döhner H, Blood 2017). Some recent evidence suggested the potential of molecular characterization for implementing the current WHO definition (Arber DA, Blood 2016), since chromatin-splicing mutations have been reported to be highly specific for sAML (Lindsley RC, Blood 2015). However, this molecular signature has also been recognized in some clinically defined de novo AML cases (Papaemmanuil E, NEJM 2016). Based on this background, we assessed the clinical impact of chromatin-splicing mutational signature in clinically defined de novo AML patients enrolled into the prospective NILG 02/06 trial [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00495287].

Patients and Methods The trial (Bassan R, Blood Advances 2019) randomized 574 newly diagnosed AML patients to receive induction (standard vs high-dose) followed by consolidative chemotherapy and/or alloSCT. For the present analysis, only patients with de novo AML (n=313) and WHO-defined sAML after MDS or MPN (n=101) with a full genetic characterization have been considered. Studies performed at diagnosis included conventional karyotype (n=412) and molecular analysis (n=414) and/or targeted NGS (this latter performed on 197 patients with normal karyotype). Patients with WHO-sAML were defined by the presence of an antecedent history of MDS or MPN (n=21) and/or cytogenetic WHO criteria of AML with MDS-related changes (n=80). Chromatin-splicing mutational signature defined the molecular-sAML group and comprised ASXL1, STAG2, BCOR, KMT2A-PTD, EZH2, PHF6, SRSF2, SF3B1, U2AF1, ZRS2 and RUNX1, excluding patients with WHO recurrent abnormalities.

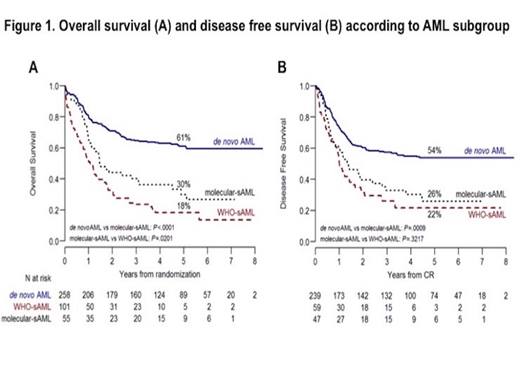

Results Chromatin-splicing mutations were scored in 55/313 (17.6%) de novo AML patients (hereafter named molecular-sAML). The most frequently reported were KMT2A-PTD (45.5%), RUNX1 (44.4%) and ASXL1 (22.2%), while other mutations in the signature accounted for 5-17.5% of cases. Compared to de novo AML without chromatin-splicing mutations, patients with molecular-sAML and WHO-sAML were older (P<0.0001) and presented with lower white blood cell counts (WBC) (P<0.0001). The 3 groups were balanced in regards to induction regimen (P=0.5) and proportion of patients allocated to a consolidative alloSCT (31% in de novo AML, 30% in WHO-sAML and 33% in molecular-sAML, P=0.8). Complete remission (CR) after 1 or 2 induction cycles was achieved in 93% of de novo AML, 85% of molecular-sAML and 58% of WHO-sAML. In terms of 5-years overall survival (OS) and disease free survival (DFS), de novo AML patients did markedly better than both molecular and WHO-sAML patients (OS: 61%, P<0.0001; DFS: 54%, P<0.0009). Considering sAML patients, WHO-sAML had the worst OS when compared with molecular-sAML (18% vs 30%, P=0.02), but an overlapping DFS (22% vs 26%, P<0.3) (Figure 1). The negative impact of chromatin-splicing mutations was independently confirmed by multivariate analysis accounting for age, performance status, WBC and induction regimen [HR 2.2 (CI 95% 1.48-3.25), P=0.0001]. Among chromatin-splicing mutations, only RUNX1 and U2AF1 significantly affected OS [HR 3.55 (CI 95% 1.28-9.87), P=0.01 and HR 6.87 (CI 95% 1.71-27.55), P=0.006]. Finally, a consolidative alloSCT improved survival in all patients groups, most significantly in molecular and WHO-sAML (48% vs 24%, P=0.07 and 38% vs 8%, P=0.0001, respectively).

Conclusions Chromatin-splicing mutational signature identifies a distinct high-risk group within de novo AML patients, which shows clinical characteristics and outcomes closer to sAML than to de novo AML patients. These data highlight the need to detect this molecular signature at diagnosis and support a molecular definition of sAML.

Ferrero:Novartis: Honoraria. Corradini:Celgene: Honoraria, Other: Travel Costs; Gilead: Honoraria, Other: Travel Costs; Jazz Pharmaceutics: Honoraria; KiowaKirin: Honoraria; Kite: Honoraria; Novartis: Honoraria, Other: Travel Costs; Daiichi Sankyo: Honoraria; AbbVie: Consultancy, Honoraria, Other: Travel Costs; Amgen: Honoraria; Janssen: Honoraria, Other: Travel Costs; Roche: Honoraria; Sanofi: Honoraria; Servier: Honoraria; Takeda: Honoraria, Other: Travel Costs; BMS: Other: Travel Costs. Bassan:Incyte: Honoraria; Amgen Inc.: Honoraria; Pfizer: Honoraria; Shire: Honoraria. Rambaldi:Roche: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Other: travel support, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau; Omeros: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Speakers Bureau; Jazz: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Speakers Bureau, travel support.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal