Key Points

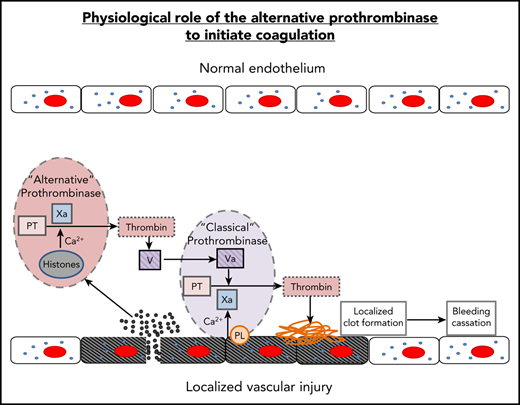

Histones substitute FVa in an alternative prothrombinase that generates thrombin without phospholipids to propagate DIC.

Histones significantly reduce FXa requirement for initiation of thrombin generation to enable coagulation in hemophilia plasma.

Abstract

Thrombin generation is pivotal to both physiological blood clot formation and pathological development of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). In critical illness, extensive cell damage can release histones into the circulation, which can increase thrombin generation and cause DIC, but the molecular mechanism is not clear. Typically, thrombin is generated by the prothrombinase complex, comprising activated factor X (FXa), activated cofactor V (FVa), and phospholipids to cleave prothrombin in the presence of calcium. In this study, we found that in the presence of extracellular histones, an alternative prothrombinase could form without FVa and phospholipids. Histones directly bind to prothrombin fragment 1 (F1) and fragment 2 (F2) specifically to facilitate FXa cleavage of prothrombin to release active thrombin, unlike FVa, which requires phospholipid surfaces to anchor the classical prothrombinase complex. In vivo, histone infusion into mice induced DIC, which was significantly abrogated when prothrombin F1 + F2 were infused prior to histones, to act as decoy. In a cohort of intensive care unit patients with sepsis (n = 144), circulating histone levels were significantly elevated in patients with DIC. These data suggest that histone-induced alternative prothrombinase without phospholipid anchorage may disseminate intravascular coagulation and reveal a new molecular mechanism of thrombin generation and DIC development. In addition, histones significantly reduced the requirement for FXa in the coagulation cascade to enable clot formation in factor VIII (FVIII)– and FIX-deficient plasma, as well as in FVIII-deficient mice. In summary, this study highlights a novel mechanism in coagulation with therapeutic potential in both targeting systemic coagulation activation and correcting coagulation factor deficiency.

Introduction

Thrombin generation is pivotal in the hemostatic response to injury. However, in critical illnesses associated with significant cell injury, increased thrombin generation is associated with the development of multiple-organ failure and the risk of mortality. A key event in thrombin generation is the assembly of the prothrombinase complex involving prothrombin, activated factor X (FXa), and activated cofactor V (FVa) in the presence of calcium and phospholipids.1 Prothrombin is a single-chain protein composed of fragment 1 (F1), fragment 2 (F2), and a protease domain (prethrombin 2, containing an A and B chain) that circulates at a concentration of 1.4 µM.2,3 F1 and F2 interact with FVa to undergo conformational changes that facilitate prothrombin cleavage by FXa to generate active thrombin.4 FVa and anionic phospholipid surfaces accelerate the rate of FXa-mediated prothrombin activation by ∼300 000-fold to enable clot localization to the site of injury.1,5-7

Currently recognized mechanisms of increased coagulation activation during critical illness include direct damage to the endothelium8 and platelets.9,10 Neutrophil extracellular traps released from neutrophils contain DNA decorated with antimicrobial proteins (eg, neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase) and histones.11 While histones are typically intranuclear in forming the basis of chromatin, they become important in host defense when released upon cell damage and/or NETosis.11 Recognized as damage-associated molecular patterns, extracellular histones are directly toxic not only to pathogens but also to host cells when in excess.12 In vitro, histones induce thrombin generation in platelet-rich plasma10 and inhibit thrombomodulin-dependent protein C activation,13 while histone infusion in mouse models cause significant cytotoxicity with dose-dependent increases in thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) complexes,14,15 prothrombotic consequences, and mortality.8,15 In critically ill patients, circulating histone levels are also significantly elevated15,16 and correlate with TAT, multiple-organ failure, and mortality.15,16

A direct action of histones on thrombin generation has also been proposed.17 Barranco-Medina et al showed that H4 and H3 can directly bind prothrombin and cause autoactivation into thrombin under buffer conditions.17 However, this takes ≤8 hours17 and was not demonstrated in plasma. Its clinical significance remains unclear, albeit raising the possibility that histones could directly induce thrombin generation. In this study, we demonstrate a novel mechanism whereby histones can substitute for FVa in prothrombinase without requiring FVa and phospholipid surfaces. Although the alternative prothrombinase is not as efficient as the classical prothrombinase (with FVa and phospholipids), it could prime coagulation by generating sufficient thrombin initially to activate FV into FVa and enable classical prothrombinase to proceed. Additionally, the phospholipid-independent and nonlocalizing nature of this mechanism could trigger systemic coagulation activation with deleterious consequences.

Methods

Human blood preparation

Blood was drawn into syringes containing one-tenth volume of 0.105 M sodium citrate from healthy volunteers after written consent (protocol approved by Liverpool University Interventional Ethical Committee, RETH000685). After 20-minute centrifugation at 2600g and 20°C, the platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was separated and stored at −80°C. Factor-deficient plasmas were purchased from Affinity Biologicals (Ancaster, ON, Canada).

Isolation of histone-binding proteins from plasma and mass spectrometry analysis

Citrated PPP was diluted with 2X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (v/v) and centrifuged twice at 20 000g for 30 minutes to eliminate insoluble material. Harvested supernatant was then precleared using blank Sepharose resin to remove nonspecific protein binding and loaded onto a CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) conjugated with calf thymus histones (Roche, Burgess Hill, United Kingdom). After stringent washing with PBS + 0.5% (v/v) Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom) followed by PBS, histone-binding proteins were eluted using 0.1 mol/L glycine (pH 3.5) and separated using 2-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis. Protein spots visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining were excised, digested with trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI), and analyzed (Velos orbitrap mass-spectrometer coupled with a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RS). Raw data were processed using PEAKS 7 software against UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot (https://www.uniprot.org/) and National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) databases.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay

Chips coated with streptavidin (Chip SA; GE Healthcare), which directly interact with histones,18 were used for immobilizing individual histones and measuring binding affinities with a Biocore X-100 system. Binding buffer (100 mmol/L NaCl and 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) and regeneration buffer (20 mmol/L HCl) were used, and 20 µg/mL of each recombinant histone (H1, H2A, H2B, H3, or H4) (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) in binding buffer was captured only on the surface of flow cell 2, with flow cell 1 set as blank. For kinetic analysis, a concentration series of each protein (prothrombin, F1, or F2) was injected at a flow rate of 10 µL/min over both captured histone and reference surfaces (blank) at 20°C. Dissociation constant (Kd) values were calculated using provided software.

In vitro prothrombin cleavage and thrombin generation

The prothrombin cleavage assay was performed as previously described, with slight modification.17,19 Prothrombin (1.5 µmol/L) (Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN) was first dialyzed against cleavage buffer (20 mmol/L N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 5 mmol/L CaCl2) and incubated with FXa (0.5 nmol/L) (New England Biolabs) without and with human histones (50 µg/mL). N-Acetyl heparin (6 µmol/L) (Sigma-Aldrich) or antihistone single-chain variable fragment antibody (ahscFv)15,16 (100 µg/mL) was preincubated with histones for 10 minutes in blocking experiments. All experiments were initiated upon addition of prothrombin and terminated by adding 4× Laemmli buffer.

Active thrombin generation was monitored using chromogenic-based functional assay. Reactions were performed at 37°C and initiated by adding calcium (5 mmol/L final concentration) and thrombin substrate S-2238 (250 µmol/L final concentration) (Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Absorbance was continually monitored at 405 nm (60 minutes, Spectromax plate reader). Thrombin concentration was calculated using commercial thrombin (Enzyme Research Laboratories) as standard.

Prothrombinase activity

To compare classical versus histone-assembled prothrombinase, prothrombin (1.5 µmol/L), FXa (0.5 nmol/L), and procoagulant phospholipids (5 µmol/L), prepared by extrusion,13 were incubated with FVa (0.5 nmol/L), H3, or H4 (50 µg/mL) in the presence of calcium (5 mmol/L). Reactions were terminated at 90 seconds by adding EDTA (10 mmol/L final concentration) and quantified by S-2238 using commercial thrombin (Enzyme Research Laboratories) as standard. To establish maximum rate (Vmax) and Michaelis constant (Km) of the H4-assemblede prothrombinase, different concentrations of prothrombin (0-6 µmol/L) were incubated with FXa (0.5 nmol/L) and H4 (50 µg/mL).20 Reactions were initiated upon the addition of calcium (5 mmol/L) and terminated after a 60-second incubation at 37°C by the addition of EDTA (10 mmol/L). Thrombin concentrations were then quantified using the thrombin substrate S-2238 (250 µmol/L) with commercial thrombin as standard. The Lineweaver-Berk equation was used to calculate the Vmax and Km from 3 experiments: 1/V0 = Km/Vmax × 1/[S] = 1/Vmax.

Computer modeling

Based on published crystal structures, the interaction between prothrombin (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession number 4HZH) and H2B (PDB accession number 5FUG), H3, or H4 (PDB accession number 4HGA) were simulated using Docking software (http://zdock.umassmed.edu) to predict the binding models and binding sites. ZDOCK searches all possible binding modes in the translational and rotational space between the 2 proteins and evaluates each pose using an energy-based scoring function. The model with the highest score in each docking is presented.

Recombinant prothrombin F1 and F2 production

Plasmids for expressing recombinant human prothrombin F1 and F2 with His-tags were synthesized by Invitrogen (Loughborough, United Kingdom), and proteins were produced in BL21 bacteria, purified using Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen, Manchester, United Kingdom).

Thrombin generation and clot formation in PPP

Thrombin generation in normal and factor-deficient PPP was performed as previously described.21 In brief, 80 µL normal, factor II (FII)–, FV-, or FX-deficient PPP was recalcified and thrombin generation continuously monitored in a 96-well plate fluorimeter (SpectraMax, San Jose, CA), using fluorogenic thrombin substrate z-GGR-AMC (Diagnostica Stago, Reading, United Kingdom). Fluorogenic detection was required in these assays due to the spectrometric interference of plasma at 405 nm. Experiments were calibrated against known thrombin concentrations. For clot formation, reactions were initiated by adding calcium (12.5mM final concentration) to PPP and light transmission monitored at 405 nm for 60 minutes in a Spectromax plate reader, at 37°C. Clot times were determined by time taken for 100% light transmission to reach a minimum plateau following recalcification.

Histone-infusion mouse models

Hemophilia experiments were performed using male and female C57BL/6 F8 exon 16 knockout (HA) mice (8-12 weeks old, body weights of ∼25 g). All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines and approved by the Queen’s University Animal Care Committee. Mice (5/group) were anesthetized with isoflurane (using oxygen as carrier gas) prior to 5 mg/kg histone H4 infusion (retro-orbital) without or with 500 µg N-acetyl heparin, which is a nonanticoagulant heparin. Mice were euthanized 1 hour after infusion. Platelet counts were performed on citrated whole blood using a Scil Vet ABC blood analyzer. Citrated plasma was isolated by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 2600g and used in coagulation assays. Clot times were determined by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) diluted 1:100 on a plate reader using light transmittance at 405 nm for 60 minutes. TAT (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) levels were determined according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

To assess the role of histones in inducing disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), male C57BL/6 mice (8-10 weeks old, body weights of 20-22g) (Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center) were used and kept in the Animal Centre of Southeast University with free access to food and water for 1 week prior to experiments, which were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines, under an approved license (Jiangsu Province, 2151981). Mice (5/group) were anesthetized with avertin (200 mg/kg) prior to histone infusion (via the tail vein) with different doses (0, 20, 30, 50, and 70 mg/kg) and euthanized 1 hour after infusion. Tissue sections were stained with antifibrin antibody (Abcam), as described previously.15 Decoy experiments were performed by infusing 10 mg/kg prothrombin F1 and F2 5 minutes prior to 60-mg/kg histone infusion.

Patient samples

Patients with sepsis (n = 144) were prospectively recruited following admittance onto the general adult intensive care unit at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital between November 2010 and October 2011, according to the protocol approved by the North West Centre of Research Ethics Committee, United Kingdom (07/H1009/64) and the Hospital Governance Committee. Written informed consent or assent was obtained from patients or next of kin, respectively. Sepsis was defined using the ACCP/SCCM 2001 International Sepsis Definition and all patients matched the criteria of Sepsis-3.22 DIC was defined using International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria.23 Circulating histones levels were determined by western blotting, according to our previous publications.15,16,24

Statistical analysis

Intergroup differences were analyzed using analysis of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test. For 2-group comparison with and without treatments, the Student t test was used to compare means. Values are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from ≥3 independent experiments. Spearman rank correlation was used for analyzing the correlation of circulating histone levels to DIC scores in septic patients. A value of P < .05 (2-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

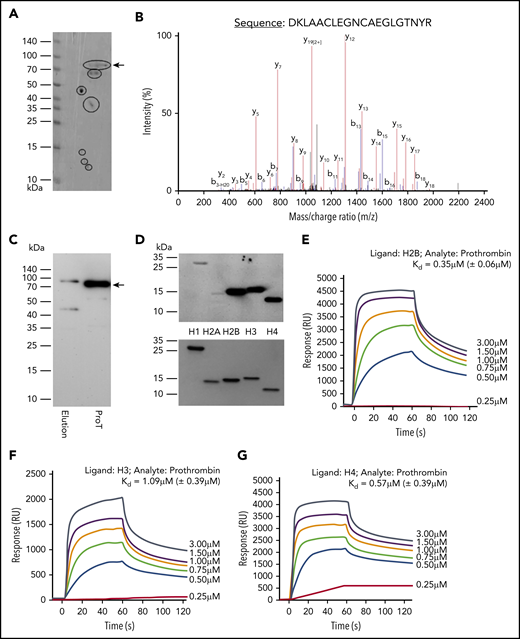

Circulating histones directly interact with prothrombin

Histone-conjugated Sepharose beads were used to pull down proteins from human plasma. After extensive washing, the proteins pulled down were subjected to 2D gel electrophoresis and 7 major histone-binding proteins were visualized (Figure 1A). Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry showed prothrombin as the only coagulation factor identified (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). This was confirmed using western blotting with a specific antibody to prothrombin (Figure 1C). H2B, H3, and H4 showed much stronger interaction with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated prothrombin than H2A and H1 (Figure 1D). Kinetically, H2B, H3, and H4 had Kd values of 0.35 µM (± 0.06 µM), 1.09 µM (± 0.39 µM), and 0.57 µM (± 0.39 µM), respectively, in biosensor assays (Figure 1E-G). The interaction did not require calcium (data not shown), and the Kd values for H1 and H2A were not calculable due to low binding responses.

Identification of prothrombin from plasma as a histone-binding protein. (A) Coomassie brilliant blue staining of histone-binding proteins (black circles) captured from plasma by histone-conjugated Sepharose and separated by 2D gel. (B) Typical liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry peaks of a peptide from trypsin-digested spot from 2D gel. (C) Western blotting of isolated histone-binding proteins using antiprothrombin antibody with commercial prothrombin (ProT) as a positive control. Arrow indicates the full length of prothrombin. (D) Gel overlay assay. Equal molar concentrations (2 µmol/L) of recombinant individual human histones were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and probed with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated prothrombin (upper panel). Lower panel: Coomassie blue–stained gel to demonstrate equal loading of proteins. (E-G) SPR curves for calculating Kd values (mean ± SD) of prothrombin with histone H2B (E), H3 (F), and H4 (G), respectively. Each experiment was repeated 3 times, and a typical experiment is presented. RU, response unit.

Identification of prothrombin from plasma as a histone-binding protein. (A) Coomassie brilliant blue staining of histone-binding proteins (black circles) captured from plasma by histone-conjugated Sepharose and separated by 2D gel. (B) Typical liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry peaks of a peptide from trypsin-digested spot from 2D gel. (C) Western blotting of isolated histone-binding proteins using antiprothrombin antibody with commercial prothrombin (ProT) as a positive control. Arrow indicates the full length of prothrombin. (D) Gel overlay assay. Equal molar concentrations (2 µmol/L) of recombinant individual human histones were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and probed with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated prothrombin (upper panel). Lower panel: Coomassie blue–stained gel to demonstrate equal loading of proteins. (E-G) SPR curves for calculating Kd values (mean ± SD) of prothrombin with histone H2B (E), H3 (F), and H4 (G), respectively. Each experiment was repeated 3 times, and a typical experiment is presented. RU, response unit.

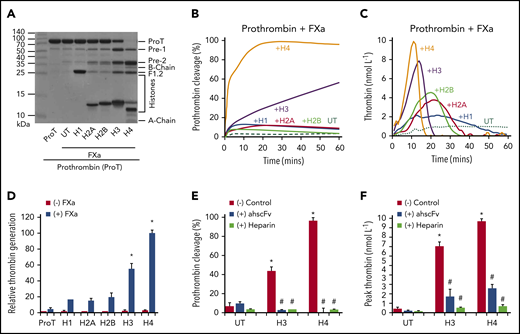

Histones enhance prothrombin cleavage and promote thrombin generation by FXa

To examine if these interactions had functional consequences, prothrombin cleavage by FXa was performed in the presence or absence of histones.17 Enhanced calcium-dependent cleavage (supplemental Figure 2) occurred from 1 minute to reach significant levels within 1 hour in the presence of H3 or H4, but not with the other histones (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 3A-B). The resultant bands include prethrombin 1, prethrombin 2, B chain, A chain, and F1.2 (Figure 2A), indicating cleavage of R320 and R271 on prothrombin, which is an essential process in generating thrombin. Additionally, chromogenic thrombin substrate S-2238 was cleaved rapidly by prothrombin and FXa in the presence of H4 or H3 (Figure 2C, D). H4 was more effective than H3, with the reaction occurring more rapidly than the reported H4-enhanced prothrombin autoactivation of ≤8 hours.17 In contrast, H1, H2A, and H2B were less effective (Figure 2A-D). AhscFv and heparin as anti-histone reagents15,16,25 inhibited H3- or H4-enhanced prothrombin cleavage (Figure 2E) and thrombin generation (Figure 2F) to demonstrate histone specificity. Prothrombin was not obviously cleaved in the absence of FXa (supplemental Figure 3C-D) or histones (supplemental Figure 3E-F), with no significant thrombin generation (Figure 2D). These data suggest that histones, prothrombin, and FXa could form functional complexes with prothrombinase activity.

Effect of individual histones on prothrombin cleavage and thrombin generation. (A) Coomassie blue–stained gel shows the cleavage of prothrombin by FXa in the presence of individual histones after 60-minute incubation with calcium (5 mmol/L) at 37°C. (B) Densitometric quantification of the percentage of prothrombin digested over time. Mean curves from 3 independent experiments are shown. (C) Thrombin generation from FXa activation of prothrombin in the presence of individual histones and calcium (5 mmol/L) with typical curves from 3 independent experiments. (D) Mean ± SD of relative thrombin generation from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 (Student t test) compared with that in the absence of histones. (E) Prothrombin cleavage by FXa in the presence of H3 or H4 without or with ahscFv (100 µg/mL) or heparin (6 µmol/L) following 60-minute incubation with calcium (5 mmol/L) at 37°C. Percentages were calculated from Coomassie blue–stained gels from 3 independent experiments (mean ± SD). Student t test shows significant increase compared with prothrombin + FXa alone untreated by histones (UT, red) (*P < .05). A significant reduction (#P < .05) was found when comparing prothrombin cleavage in the absence or presence of anti-histone reagents to histones alone. (F) The effects of ahscFv and heparin on thrombin generation presented as mean ± SD of thrombin (nmol/L). Student t test shows a significant increase compared with prothrombin + FXa alone untreated by histones (UT, red) (*P < .05). A significant reduction (#P < .05) was found when comparing thrombin in the absence or presence of antihistone reagents to histones alone.

Effect of individual histones on prothrombin cleavage and thrombin generation. (A) Coomassie blue–stained gel shows the cleavage of prothrombin by FXa in the presence of individual histones after 60-minute incubation with calcium (5 mmol/L) at 37°C. (B) Densitometric quantification of the percentage of prothrombin digested over time. Mean curves from 3 independent experiments are shown. (C) Thrombin generation from FXa activation of prothrombin in the presence of individual histones and calcium (5 mmol/L) with typical curves from 3 independent experiments. (D) Mean ± SD of relative thrombin generation from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 (Student t test) compared with that in the absence of histones. (E) Prothrombin cleavage by FXa in the presence of H3 or H4 without or with ahscFv (100 µg/mL) or heparin (6 µmol/L) following 60-minute incubation with calcium (5 mmol/L) at 37°C. Percentages were calculated from Coomassie blue–stained gels from 3 independent experiments (mean ± SD). Student t test shows significant increase compared with prothrombin + FXa alone untreated by histones (UT, red) (*P < .05). A significant reduction (#P < .05) was found when comparing prothrombin cleavage in the absence or presence of anti-histone reagents to histones alone. (F) The effects of ahscFv and heparin on thrombin generation presented as mean ± SD of thrombin (nmol/L). Student t test shows a significant increase compared with prothrombin + FXa alone untreated by histones (UT, red) (*P < .05). A significant reduction (#P < .05) was found when comparing thrombin in the absence or presence of antihistone reagents to histones alone.

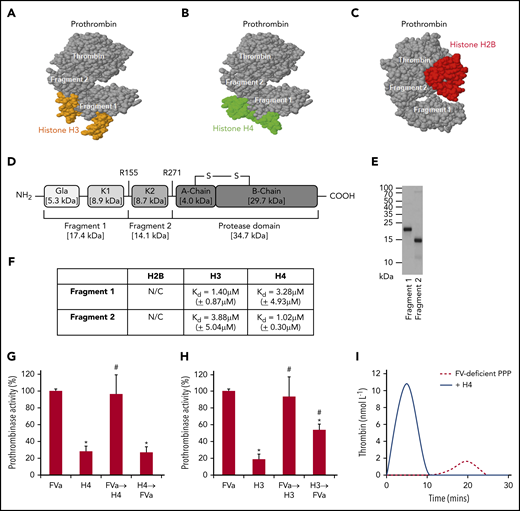

Histone H3 and H4 bind prothrombin F1 and F2 to replace FVa and assemble an alternative prothrombinase complex

To understand how histones enhance prothrombin cleavage to generate thrombin, their binding sites on prothrombin were investigated. Using Docking software, both prothrombin F1 and F2 regions were predicted as the binding sites for H3 or H4 (Figure 3A-B), while the protease (thrombin) domain was the predicted binding site for H2B (Figure 3C). Based on human prothrombin sequence (Figure 3D), recombinant F1 and F2 peptides were designed and produced in Escherichia coli (Figure 3E). Using SPR, both F1 and F2 interacted with H3 (F1 Kd = 1.40 µM [±0.87 µM]; F2 Kd = 3.88 µM [±5.04 µM]) or H4 (F1 Kd = 3.28 µM [±4.93 µM]; F2 Kd = 1.02 µM [±0.30 µM]) with similar affinity (Figure 3F; supplemental Figure 4) as that reported between prothrombin and FVa (Kd ∼2.00 µM).26 H2B data were not calculable due to low binding responses. These data suggest that both H3 and H4 behave like FVa in cofactor facilitation of prothrombin cleavage by FXa to generate active thrombin.26 To examine and contrast their relative contributions toward thrombin generation, assessment of prothrombinase activity found no synergism of effects when FVa and H3 or H4 were combined (Figure 3G-H). When H3 or H4 was added before FVa, thrombin generation was significantly reduced compared with FVa alone (or if histones were added after FVa). This suggests that H3 or H4 could compete with FVa for prothrombin activation, although the histone-prothrombin-FXa complex is less effective in generating thrombin than assembly of FVa-prothrombin-FXa.

Histone H3 and H4 binding to F1 and F2 of prothrombin competes with FVa. Computer prediction using the ZDOCK server shows that H3 (PDB: 4HGA) (A), H4 (PDB: 4HGA) (B), and H2B (PDB: 5FUG) (C) bind to prothrombin (PDB: 4HZH). Specifically, H3 and H4 recognize prothrombin F1 and F2, while H2B recognizes the protease domain (thrombin). (D) Schematic representation of F1, F2, and protease domains of prothrombin. (E) Coomassie blue–stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel showing purified prothrombin F1 and F2 produced in BL21 bacteria. (F) Binding affinities (Kd) of H2B, H3, and H4 to prothrombin F1 and F2 by SPR kinetic assay. Means ± SD are presented from 3 independent experiments. N/C, none calculable. Prothrombinase activity from FXa activation of prothrombin in the presence of phospholipids (40% phosphatidylcholine, 20% phosphatidylserine, and 40% phosphatidylethanolamine) and FVa, with or without either H4 (G) or H3 (H). All reactions were performed for 90 seconds in the presence of calcium (5 mmol/L) and terminated by the addition of EDTA (10 mmol/L). Data are represented as a percentage of classical prothrombinase activity (mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments). Student t test shows a significant decrease in prothrombinase activity compared with the absence of histones (*P < .05) and a significant increase in prothrombinase activity compared with H3 or H4 alone (#P < .05). Arrow indicates the order in which the competing reagents were added. (I) Thrombin generation in recalcified FV-deficient PPP ± H4 (50 µg/mL).

Histone H3 and H4 binding to F1 and F2 of prothrombin competes with FVa. Computer prediction using the ZDOCK server shows that H3 (PDB: 4HGA) (A), H4 (PDB: 4HGA) (B), and H2B (PDB: 5FUG) (C) bind to prothrombin (PDB: 4HZH). Specifically, H3 and H4 recognize prothrombin F1 and F2, while H2B recognizes the protease domain (thrombin). (D) Schematic representation of F1, F2, and protease domains of prothrombin. (E) Coomassie blue–stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel showing purified prothrombin F1 and F2 produced in BL21 bacteria. (F) Binding affinities (Kd) of H2B, H3, and H4 to prothrombin F1 and F2 by SPR kinetic assay. Means ± SD are presented from 3 independent experiments. N/C, none calculable. Prothrombinase activity from FXa activation of prothrombin in the presence of phospholipids (40% phosphatidylcholine, 20% phosphatidylserine, and 40% phosphatidylethanolamine) and FVa, with or without either H4 (G) or H3 (H). All reactions were performed for 90 seconds in the presence of calcium (5 mmol/L) and terminated by the addition of EDTA (10 mmol/L). Data are represented as a percentage of classical prothrombinase activity (mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments). Student t test shows a significant decrease in prothrombinase activity compared with the absence of histones (*P < .05) and a significant increase in prothrombinase activity compared with H3 or H4 alone (#P < .05). Arrow indicates the order in which the competing reagents were added. (I) Thrombin generation in recalcified FV-deficient PPP ± H4 (50 µg/mL).

When H4 was added to prothrombin in the presence of FXa and phospholipid, consequent addition of FVa could not further increase prothrombinase activity and vice versa (Figure 3G). However, when FVa was added after H3, the activity could be significantly increased, but not to levels reached by classical prothrombinase, although adding H3 after FVa could not change the activity (Figure 3H). These observations suggest that H4, but not H3, could fully occupy the FVa binding sites on prothrombin and affect its conformation to enable FXa access and cleavage. Addition of histones to FV-deficient plasma restored thrombin-generating capacity, without FVa supplementation (Figure 3I; supplemental Figure 5), to indicate that H3 or H4 could substitute FVa in forming active prothrombinase. To distinguish it from FVa-assembled classical prothrombinase,7 the histone-mediated complex is termed the alternative prothrombinase in this paper.

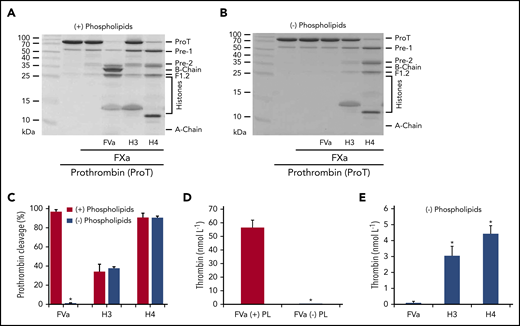

Alternative prothrombinase, unlike classical prothrombinase, is phospholipid independent

Phospholipids are essential for prothrombin cleavage by FVa-assembled prothrombinase (Figure 4A-C) and thrombin generation (Figure 4D), which is consistent with published reports.1 In the presence of phospholipids, 56.24 ± 5.42 nmol/L thrombin was generated in 90 seconds (P < .001). In their absence, prothrombin cleavage was not detectable, with only trace amounts of thrombin generated (0.095 ± 0.094 nmol/L in 90 seconds) (Figure 4D,E). However, the presence or absence of phospholipids had no effect on prothrombinase activity or prothrombin cleavage when FVa was substituted by H4 (4.71 ± 0.52 vs 4.42 ± 0.52 nmol/L, P > .05) or H3 (3.43 ± 0.66 vs 3.03 ± 0.62 nmol/L, P > .05) (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 6). In the absence of phospholipids, H4 and H3 were much more effective in facilitating active thrombin generation than FVa (Figure 4E). Using the Lineweaver-Berk equation, 1/V0 = Km/Vmax × 1/[S] = 1/Vmax, we calculated the Vmax = 49.2 ± 0.61 mol/min mol FXa and Km = 1.2 ± 0.05 µmol/L for histone H4–assembled alternative prothrombinase. These observations suggest that unlike FVa, H4 and H3 enhancement of prothrombinase is not dependent on phospholipid surface availability or localization to the site of injury and could therefore contribute to systemic thrombin generation when circulating histone concentrations are elevated.

Histones enhance thrombin generation in the absence of FV and phospholipids. (A-B) Prothrombin cleavage by FXa in the presence of FVa, H3, or H4 with (A) or without (B) phospholipids (40% phosphatidylcholine, 20% phosphatidylserine, and 40% phosphatidylethanolamine) after 60-minute incubation with calcium (5 mmol/L) at 37°C. (C) Densitometric quantification of prothrombin bands from gels (A and B), presented as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Student t test shows a significant decrease in prothrombin cleavage in the absence of phospholipids (*P < .05). (D) Thrombin generation from FXa activation of prothrombin in the presence of FVa with (+) or without (−) phospholipids (PL). All reactions were performed for 90 seconds in the presence of calcium (5 mmol/L) and terminated by the addition of EDTA (10 mmol/L) (mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments). Student t test shows significant decrease in prothrombin generation in the absence of phospholipids (*P < .05). (E) Thrombin generation during 90 seconds activation of prothrombin by FXa with FVa, H3, or H4 in the presence of calcium (5 mmol/L) and absence of phospholipids (mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments). Student t test shows a significant increase in thrombin generation compared with FVa (*P < .05).

Histones enhance thrombin generation in the absence of FV and phospholipids. (A-B) Prothrombin cleavage by FXa in the presence of FVa, H3, or H4 with (A) or without (B) phospholipids (40% phosphatidylcholine, 20% phosphatidylserine, and 40% phosphatidylethanolamine) after 60-minute incubation with calcium (5 mmol/L) at 37°C. (C) Densitometric quantification of prothrombin bands from gels (A and B), presented as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. Student t test shows a significant decrease in prothrombin cleavage in the absence of phospholipids (*P < .05). (D) Thrombin generation from FXa activation of prothrombin in the presence of FVa with (+) or without (−) phospholipids (PL). All reactions were performed for 90 seconds in the presence of calcium (5 mmol/L) and terminated by the addition of EDTA (10 mmol/L) (mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments). Student t test shows significant decrease in prothrombin generation in the absence of phospholipids (*P < .05). (E) Thrombin generation during 90 seconds activation of prothrombin by FXa with FVa, H3, or H4 in the presence of calcium (5 mmol/L) and absence of phospholipids (mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments). Student t test shows a significant increase in thrombin generation compared with FVa (*P < .05).

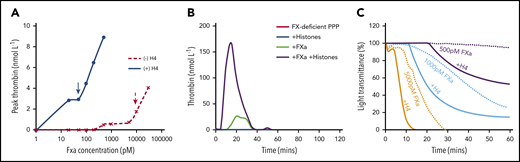

The alternative prothrombinase-initiated clot formation requires less FXa

Although high FXa concentrations can directly generate FVa and thrombin to amplify clot formation,27,28 very low FXa levels (picomolar concentrations) are produced in the initiation phase.29 It remains a paradox as to whether such concentrations are sufficient to generate critical levels of thrombin and FVa to initiate clot formation.29,30 Therefore, important contributing factors to the hemostatic response to injury remain to be identified. To explore whether histones released following cell damage play an important role in the initial phase prior to FV activation, different FXa concentrations were investigated in both thrombin generation and clotting assays, with or without histones. Significant thrombin generation only occurred when FXa reached ∼10 nM in the absence of both histones and FVa, while only 50 to 100 pM of FXa (100× less) was required in the presence of 50 μg/mL histone H4 (Figure 5A). Using FX-deficient plasma, we could control the concentration of FXa by adding exogenous FXa. No detectable thrombin was generated after recalcifying the deficient PPP. When 500 pM FXa was supplemented, thrombin generation was significant enhanced in the presence of 50 μg/mL H4 compared to that without histones (Figure 5B). To initiate clot formation by recalcifying FX-deficient PPP, only 500 pM FXa was required in the presence of 50 μg/mL H4, while ≥1000pM FXa was required in the absence of histones (Figure 5C). At 5000 pM FXa, H4 reduced clot time to ∼10 minutes as compared with >20 minutes when histones were absent (Figure 5C). These data suggest that histones enhance and facilitate the initiation of clot formation.

Histones reduce the demand for FXa to initiate clot formation. (A) Thrombin generation from FXa activation of prothrombin in the presence of different concentrations of FXa ± H4 (50 µg/mL). (B) Typical thrombin generation curve in recalcified FX-deficient PPP ± FXa (500 pmol/L) ± histones (50 µg/mL). (C) Clot formation of recalcified (12.5 mmol/L) FX-deficient plasma ± H4 (50 µg/mL) supplemented with 500, 1000, or 5000 pM FXa.

Histones reduce the demand for FXa to initiate clot formation. (A) Thrombin generation from FXa activation of prothrombin in the presence of different concentrations of FXa ± H4 (50 µg/mL). (B) Typical thrombin generation curve in recalcified FX-deficient PPP ± FXa (500 pmol/L) ± histones (50 µg/mL). (C) Clot formation of recalcified (12.5 mmol/L) FX-deficient plasma ± H4 (50 µg/mL) supplemented with 500, 1000, or 5000 pM FXa.

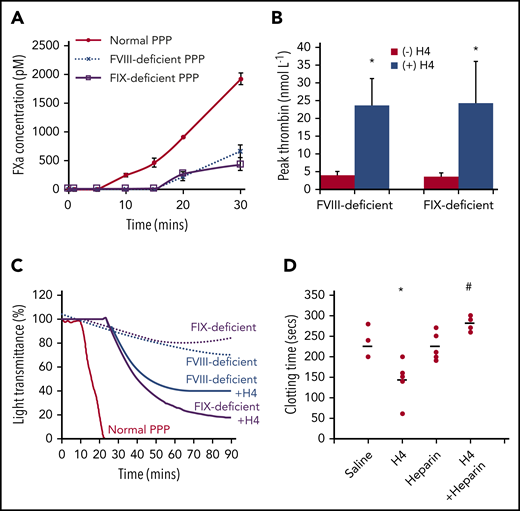

Alternative prothrombinase formation enhances clot formation in hemophilia

FXa production is amplified through the intrinsic pathway, following the initiation stage, to generate sufficient FXa for clot formation. However, this pathway is disabled in hemophilia due to the absence of FVIII or FIX, and consequently, insufficient FXa production potentiates bleeding (supplemental Figure 7). Maximal FXa levels generated in FVIII- or FIX-deficient plasma (∼200 pM) were less than one-quarter of that in normal plasma (∼1000 pM) 20 minutes after recalcification (Figure 6A). As a result, very low thrombin concentrations were generated in the FVIII- or FIX-deficient plasmas unless histones were added (Figure 6B). Thrombin generation dramatically increased with 50 μg/mL H4. Recalcifying normal plasma induced clot formation, but not in FVIII- or FIX-deficient plasma, even after increasing incubation times (Figure 6C). Upon addition of 50 μg/mL histone H4, recalcification resulted in clot formation of FVIII- or FIX-deficient plasma. In FVIII-deficient mice, injection of 5 mg/kg histone H4 shortened the dilute aPTT clot times by ∼40% compared with saline controls (P = .021) (Figure 6D). This could be abrogated in the presence of nonanticoagulant heparin to neutralize histones (P = .002). These data confirm that histones enable more efficient thrombin generation at low FXa levels to facilitate clot formation in hemophilia.

Histones enhance clot formation in hemophilia. (A) FXa concentrations (pM) following recalcification of normal, FVIII-deficient, and FIX-deficient PPP. (B) Histone H4 (50 μg/mL) enhances thrombin generation in FVIII- and FIX-deficient plasma. (C) Histone H4 (50 μg/mL) (solid lines) induced clot formation in FVIII and FIX-deficient plasma following recalcification. There was no clot formation in the deficient plasmas (dotted lines), and normal plasma clot time (red) is shown for comparison. (D) FVIII-deficient mice were anesthetized and infused with histone H4 (5 mg/kg) retro-orbitally with and without intraperitoneal infusion of nonanticoagulant heparin (500 µg/mice) to neutralize histones. One hour after infusion, bloods were taken for dilute aPTT assays. Clot times (seconds) for each individual mouse (dots), from 5 mice per group, are presented along with mean values for each group (lines). *P < .05 (analysis of variance) compared with the absence of histones; #P < .05 compared with histones alone.

Histones enhance clot formation in hemophilia. (A) FXa concentrations (pM) following recalcification of normal, FVIII-deficient, and FIX-deficient PPP. (B) Histone H4 (50 μg/mL) enhances thrombin generation in FVIII- and FIX-deficient plasma. (C) Histone H4 (50 μg/mL) (solid lines) induced clot formation in FVIII and FIX-deficient plasma following recalcification. There was no clot formation in the deficient plasmas (dotted lines), and normal plasma clot time (red) is shown for comparison. (D) FVIII-deficient mice were anesthetized and infused with histone H4 (5 mg/kg) retro-orbitally with and without intraperitoneal infusion of nonanticoagulant heparin (500 µg/mice) to neutralize histones. One hour after infusion, bloods were taken for dilute aPTT assays. Clot times (seconds) for each individual mouse (dots), from 5 mice per group, are presented along with mean values for each group (lines). *P < .05 (analysis of variance) compared with the absence of histones; #P < .05 compared with histones alone.

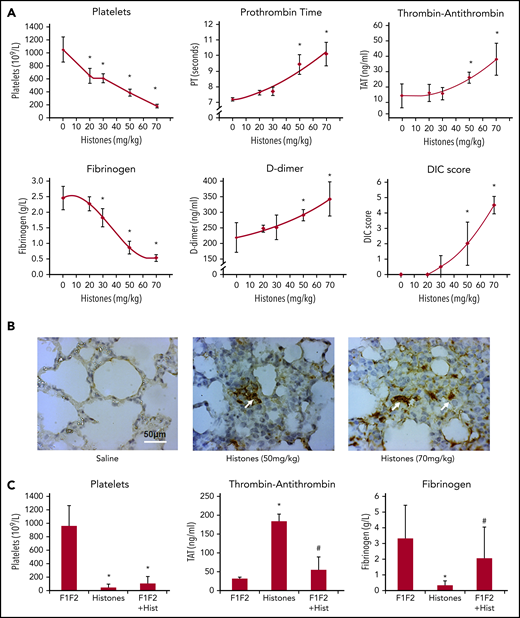

Prothrombin F1 and F2 reduce histone-induced systemic coagulation activation in vivo

To explore the role of circulating histones in DIC, different histone concentrations were infused into mice. We observed significant falls in platelet counts and fibrinogen levels, and elevation in TAT, D-dimer, and prothrombin time in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 7A). Intravascular thrombi were found in different organs, particularly in lungs (Figure 7B). Consistent with the findings of others, histones (>30 mg/kg) induced DIC in mice.31 By infusing 10 mg/kg prothrombin F1 and F2 prior to 60-mg/kg histone infusion, platelet counts were similarly lowered to that in histone-infused mice (Figure 7C, left), indicating that the fragments are unable to neutralizing histone cytotoxicity. In contrast, histone-induced TAT elevation and histone-induced fibrinogen consumption were significantly reduced (Figure 7C, middle and right), indicating prothrombin F1 and F2 act as a decoy to prothrombin to significantly suppress histone-induced thrombin generation. In patients with sepsis (n = 144), elevated circulatory histone levels were significantly elevated in patients with DIC (supplemental Figure 8; P = .022). These data support that histone-induced alternative prothrombinase is an important mechanism in promoting systemic coagulation.

Prothrombin F1 and F2 alleviate histone-induced systemic coagulation activation in vivo. C57BL/6 male mice were anesthetized and infused with different doses of histones through tail veins. One hour after infusion, blood were taken for platelet count, prothrombin time (PT) and concentrations of TAT complexes, fibrinogen, and D-dimer; DIC scores were also calculated (A). (B) Lung sections from histone-infused mice and saline controls were immunohistochemically stained with anti-fibrin antibody, and typical images are presented. Arrows indicate thrombi. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Platelet counts (left), TAT (middle), and fibrinogen (right) levels following prothrombin F1 + F2 infusion ± histones. *P < .05 compared to F1/F2 alone; #P < .05 when compared to histones alone (ANOVA).

Prothrombin F1 and F2 alleviate histone-induced systemic coagulation activation in vivo. C57BL/6 male mice were anesthetized and infused with different doses of histones through tail veins. One hour after infusion, blood were taken for platelet count, prothrombin time (PT) and concentrations of TAT complexes, fibrinogen, and D-dimer; DIC scores were also calculated (A). (B) Lung sections from histone-infused mice and saline controls were immunohistochemically stained with anti-fibrin antibody, and typical images are presented. Arrows indicate thrombi. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Platelet counts (left), TAT (middle), and fibrinogen (right) levels following prothrombin F1 + F2 infusion ± histones. *P < .05 compared to F1/F2 alone; #P < .05 when compared to histones alone (ANOVA).

Discussion

Histones are nuclear proteins that are released into circulation after cell damage or NETosis.15,32,33 Although extracellular histones have already been demonstrated to be procoagulant, our finding provides a novel mechanism for direct histone-enhanced coagulation in the physiological and pathological response to injury. In addition, this new understanding forms the basis of potential therapeutic strategies in hemophilia and DIC.

Regulated thrombin generation is pivotal in localizing the hemostatic response to injury, but sustained and dysregulated generation can lead to systemic dissemination, which contributes to the pathogenesis of critical illness in worsening disease severity.34 Typically, classical prothrombinase assembly occurs at altered phospholipid surfaces (eg, activated platelets or damaged endothelial cell membranes), but not on normal cell surfaces or in solution.35,36 Such a localizing mechanism of coagulation serves to prevent dissemination and minimize dysregulation.37 However, our findings raise the possibility that the phospholipid-independent nature of circulating histone-induced thrombin generation could be pathogenic (supplemental Figure 9). In particular, significant elevation of circulating histones, such as during severe trauma, sepsis, or pancreatitis, could form alternative prothrombinase in the circulation to increase thrombin-mediated systemic activation of coagulation.38 Our findings that infusion of histones into mice leads to DIC and that circulating histone levels strongly correlate with DIC scores in critically ill patients further support the important role that high circulating histones play.14,15 Histone-mediated alternative prothrombinase without anchoring to altered phospholipid surfaces may be a major mechanism of the disseminating coagulation.

It is known that extracellular histones also promote thrombin generation through damaging endothelial and hematopoietic cells.8-10,13,39,40 Loss of thrombomodulin-dependent protein C activation has been described,13 as has histone-induced platelet activation.10 Prostaglandin E1 inhibition of platelet activation can significantly reduce histone-induced thrombin generation.10 In our experiments, Prostaglandin E1 reduced histone-induced thrombin generation in platelet-rich plasma by >50% but had no significant effect in PPP (supplemental Figure 10). On the other hand, platelet depletion occurs rapidly (within minutes) in histone-infused mice,14,39 in a manner similar to thrombocytopenia development in critically ill patients. In contrast, our findings of histone-induced alternative prothrombinase provides a direct mechanism of procoagulant histones. Importantly, significant reversal of histone-induced TAT and fibrinogen changes by coinfusing prothrombin F1 and F2 strongly supports that alternative prothrombinase formation is the major mechanism of histone-enhanced thrombin generation and coagulation activation in vivo.

In the initiation phase of coagulation, production of thrombin to convert FV to FVa is crucial to the amplification process. How this is achieved is still an unresolved paradox.29 Certain proteases have been reported to cleave FV, including neutrophil elastase,41 FVIIa,42 FXIa,43 platelet-localized proteases,44 and calpain,45 but none have demonstrated efficacy in clot initiation. Although picomolar concentrations of FXa produced by extrinsic tenase during this phase has been predicted by computing simulation to be able to produce thrombin in the presence of saturating phospholipids,29 this amount of thrombin may not be sufficient to generate enough FVa to accelerate the process until high FXa concentrations become available.28,29 In this study, we demonstrated that the demand for FXa to initiate thrombin generation and clot formation is lowered by 100- to 1000-fold in the presence of histones. The alternative prothrombinase (Vmax = 49.2 ± 0.61 mol/min mol FXa; Km = 1.2 ± 0.05 µmol/L) is less efficient than the classical prothrombinase (Vmax = 1919 mol/min mol FXa; Km = 0.21µmol/L).1 However, sufficient thrombin was generated by the alternative prothrombinase to reach a critical level that is sufficient for activating FV and the intrinsic pathway to amplify coagulation. Following vascular injury, the released histones may be sufficiently concentrated to prime the coagulation cascade. Therefore, histone exposure and alternative prothrombinase formation may be the key to solve the FV activation paradox.

Clinically, the amplification of FXa production is blocked in hemophilia due to lack of FVIII or FIX. Insufficient FXa production leads to bleeding following injury. However, the clot-forming capacity of FVIII- and FIX-deficient plasma was restored in the presence of H4 following recalcification, although not to normal levels. Low levels of thrombin are generated following recalcification of hemophilia plasma, but a significant increase was observed following addition of H4. This also has in vivo relevance, as low-dose histones (5 mg/kg) could significantly induce clotting in FVIII-deficient mice without inducing thrombocytopenia or systemic activation of coagulation (Figure 6D; supplemental Figure 11). These data confirm that less FXa was required for clot formation in the presence of histones.

A limitation of this study is the difficulty in accurately evaluating the contribution of histone-assembled prothrombinase in vivo because of the multiple targets and effects on coagulation activation by histones and the lack of a viable FV knockout in vivo model. However, the histone concentrations used in this study are in keeping with circulating histone levels detected in many critically ill patients15,16,46 that have been shown to correlate significantly with TAT levels. Furthermore, circulating histone levels remain high (>30 µg/mL) for several hours, and the conditions in which prothrombin activation occurs would also be affected by dynamic changes in prothrombin, FXa and FVa levels from ongoing consumptive coagulopathy. Collectively, our findings indicate that anti-histone therapy may hold promise in preventing or reducing the extent of the dysregulated coagulation in patients with high, sustained levels of circulating histones.

For original data, please e-mail the corresponding author.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Colin Downey at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital for his technical assistance and Angela Platt-Higgins at the University of Liverpool for animal tissue processing. The authors also thank Holly Birchough and Thomas Jowitt at the University of Manchester for assistance with the SPR assay, as well as Philip Rudland at the University of Liverpool for critical reading of the manuscript and other support.

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (PG/14/19/30751 and PG/16/65/32313) (G.W., C.-H.T., and S.T.A.), the National Institute for Health Research (II-FS-0110-14061) (C.-H.T., G.W., and S.T.A.), a Newton Fellowship (Z.L.), and a Bayer Hemophilia Award (C.-H.T.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.T.A., D.S., and Y.S. performed in vitro experiments and analyzed the data, assisted by Y.A., who also analyzed the clinical data; M.D. performed the computing modeling and some of the western blotting; J.H.F. and M.H. performed part of the in vitro experiments and interpreted data in the manuscript; Z.C. performed in vivo experiments to assess the role of histones in developing DIC; Z.L. processed and analyzed the tissue sections and blood samples from mice; K.N. performed hemophilia mice model experiments supervised by D.L., who interpreted the data; S.T.A., Y.A., G.W., and C.-H.T. wrote, edited, and reviewed the manuscript and figures; and G.W. and C.-H.T. designed and supervised the work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cheng-Hock Toh, Institute of Infection and Global Health, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7BE, United Kingdom; e-mail: toh@liverpool.ac.uk; and Guozheng Wang, Institute of Infection and Global Health, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7BE, United Kingdom; e-mail: wangg@liverpool.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

Author notes

S.T.A. and D.S. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal