Bye and colleagues employed a new way to look at the thrombosis that accompanies COVID-19 infection.1 In this issue of Blood, they have identified that aberrant glycosylation of the anti-spike IgG leads to greater prothrombotic platelet activation via FcγRIIA.

Over the past 2 decades, the interplay among immunity, inflammation, hemostasis, and thrombosis has been more clearly appreciated. Advances in fundamental immunology have translated into improved understanding of the relationship of human thrombotic disorders and immune stimuli. This work by Bye and colleagues fits nicely into that tradition. Thrombosis related to COVID-19 is important and incompletely understood. It is clearly multifactorial, with alterations of endothelial cells and activation of leukocytes, platelets, and coagulation. Since the beginning of the pandemic, clinicians have recognized that critical pulmonary (acute respiratory distress syndrome with pulmonary vascular thrombosis) and systemic (deep vein thrombosis) manifestations of COVID-19 infection are often pronounced when adaptive immunity has begun. IgG is an important component of the adaptive response. Immunoglobulin (IgG) undergoes N-glycosylation of the heavy chain in the Fc region during biosynthesis (see figure). The nature of these sugars in circulating IgG has been well studied, consistent with fucose and galactose residues being regulated in a narrow range. New fundamental studies have identified reduced fucosylation and increased galactosylation status of the IgG in response to certain viral infections, including HIV and dengue, and indicate that it may be a generalizable feature of the early IgG response to enveloped viruses that bud from cells.2-4

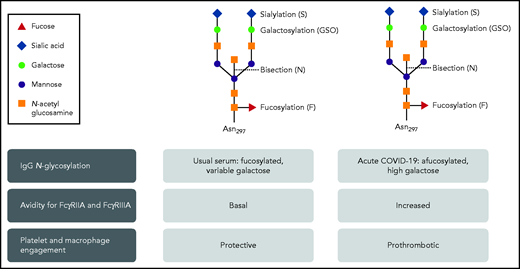

The N-glycosylation of IgG in severe acute COVID-19 infection has a variant pattern that has greater avidity for FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIA. As a result, platelet and macrophage engagement is prothrombotic. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

The N-glycosylation of IgG in severe acute COVID-19 infection has a variant pattern that has greater avidity for FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIA. As a result, platelet and macrophage engagement is prothrombotic. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Enter the human IgG response to the COVID-19 spike protein. Bye et al build on the data of reduced fucosylation and increased galactosylation of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG directed against the spike protein to pursue the prothrombotic effects on platelets. A recombinant antispike IgG (Cova1-18) cloned from a patient5 was modified to have usual glycosylation or low fucose (fuc) or high galactose (gal), or both. Only the low fuc/high gal IgG supported platelet accumulation over a von Willebrand factor (VWF)-coated surface in a flow chamber, at both venous and arterial shear rates. Bye et al decided to use the VWF-coated surface based on observations in vivo and ex vivo of high vWF on endothelial surfaces during COVID-19 infection. They show that prothrombotic platelet activation depends on interaction of the spike protein/Cova1-18 anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG immune complex with FcγRIIa, the sole Fcγ receptor on human platelets that is capable of mediating immunity and thrombosis.6 Additional evidence includes blockade of FcγRIIA with the anti-FcγRIIA ligand-blocking antibody IV.3 and reduction in activation with inhibitors to known platelet-signaling components downstream of FcγRIIA (Syk, Btk, and P2Y12).

Together with a related study of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG stimulation of alveolar macrophages,4 Bye et al show that both FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIA have increased avidity for the IgG Fc end that presents low-fuc/high-gal modifications. The result is increased effector functions, which in this case are prothrombotic. This paradigm is a new one for antibody-dependent inflammation contributing to prothrombotic effects (see figure). The new appreciation of the interactions of underfucosylated/overgalactosylated IgG with Fcγ receptors could advance the understanding and management of COVID-19, coagulopathies from other enveloped viruses, and other immune thrombotic thrombocytopenic disorders.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal