Key Points

MZ B cells can regulate a CD4 T-cell–dependent antibody response to RBCs.

MZ B-cell–mediated antibody formation to RBCs can occur independently of follicular B cells.

Abstract

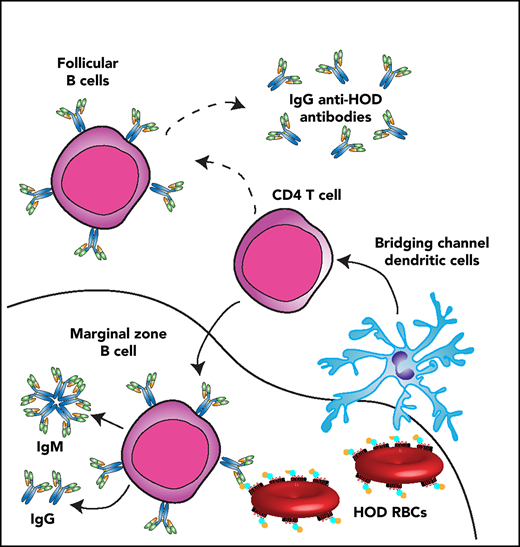

Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions can result in alloimmunization toward RBC alloantigens that can increase the probability of complications following subsequent transfusion. An improved understanding of the immune mechanisms that underlie RBC alloimmunization is critical if future strategies capable of preventing or even reducing this process are to be realized. Using the HOD (hen egg lysozyme [HEL] and ovalbumin [OVA] fused with the human RBC antigen Duffy) model system, we aimed to identify initiating immune factors that may govern early anti-HOD alloantibody formation. Our findings demonstrate that HOD RBCs continuously localize to the marginal sinus following transfusion, where they colocalize with marginal zone (MZ) B cells. Depletion of MZ B cells inhibited immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG anti-HOD antibody formation, whereas CD4 T-cell depletion only prevented IgG anti-HOD antibody development. HOD-specific CD4 T cells displayed similar proliferation and activation following transfusion of HOD RBCs into wild-type or MZ B-cell–deficient recipients, suggesting that IgG formation is not dependent on MZ B-cell–mediated CD4 T-cell activation. Moreover, depletion of follicular B cells failed to substantially impact the anti-HOD antibody response, and no increase in antigen-specific germinal center B cells was detected following HOD RBC transfusion, suggesting that antibody formation is not dependent on the splenic follicle. Despite this, anti-HOD antibodies persisted for several months following HOD RBC transfusion. Overall, these data suggest that MZ B cells can initiate and then contribute to RBC alloantibody formation, highlighting a unique immune pathway that can be engaged following RBC transfusion.

Introduction

Although transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs) represents one of the most common medical procedures, as with any therapeutic endeavor, it is not without risk. Polymorphisms on donor RBCs can stimulate alloantibody formation and complicate the management of subsequent transfusion.1-3 Challenges associated with RBC alloimmunization are particularly pronounced in transfusion-dependent patients, such as individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD). Alloantibodies in these patients can delay the procurement of compatible blood and exacerbate the underlying complications of severe anemia, directly leading to increased morbidity and mortality.2,4-8 RBC alloantibodies can also increase the likelihood of life-threatening hemolytic transfusion reactions3,9-11 and prevent patients at risk for stroke and other SCD-related complications from fully benefiting from prophylactic transfusion measures.12 In a similar manner, although several highly promising strategies exist to cure SCD,13-19 these approaches often require peritransplant transfusion support that can be challenging to achieve in alloimmunized patients. Therefore, RBC alloimmunization remains a potential barrier to these disease-curing options.

Although attempts to match common alloantigen targets prior to transfusion have resulted in reduced alloantibody formation in at-risk patients,20 unfortunately, these approaches fail to fully prevent alloimmunization.21,22 As a result, complementary strategies capable of actively preventing RBC alloimmunization may be helpful. However, because RBC alloantigens vary with respect to structure, function, and overall propensity to induce alloantibody formation, the identification and then targeting of common pathways required to initiate alloimmunization against a diverse range of alloantigens will likely enhance the probability that such approaches will be successful. Previous studies have demonstrated that RBC alloantigens can engage immune pathways similar to those believed to drive antibody formation against other antigens, including CD4 T follicular helper cells (TFHs)23 and follicular (FO) B cells.24-28 TFH engagement of FO B cells is believed to drive germinal center (GC) reactions that are necessary for long-lived antibody formation.29,30 Consistent with this, many strategies under consideration for the prevention of RBC alloimmunization are understandably aimed at inhibiting immune processes that support TFH or FO B-cell–mediated antibody formation associated with GC reactions.

Although efforts to target FO B-cell and TFH responses are promising, defining key initiating immune pathways that may be triggered before FO B-cell and TFH activation occurs may allow inhibition of this response before downstream amplification of the immune response. In doing so, identifying early immune players in alloimmunization may provide complementary strategies aimed at favorably modulating these pathways. This may be especially important when considering that recent studies suggest that, for some model antigens, such as KEL, immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-KEL antibody formation can develop through a marginal zone (MZ) B-cell–dependent, yet CD4 T-cell–independent, pathway.31 These unexpected findings led us to examine whether similar pathways can be engaged by other alloantigens. To this end, we used an alternative model system that utilizes the HOD target antigen (hen egg lysozyme [HEL] and ovalbumin [OVA] fused with the human RBC antigen Duffy). Our results indicate that, although MZ B cells mediate HOD alloimmunization, HOD RBCs induce a CD4 T-cell–dependent immune pathway distinct from KEL. Because initiating pathways may reflect common nodes in the immune response to RBC alloantigens, these results provide important insight into possible early immune events that may be engaged following exposure to multiple alloantigens.

Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 (B6) recipient mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). B6 mice that underwent splenectomy or sham procedure were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). CD19Cre and Notch2flx mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and used to generate (CD19Cre/+ × Notch2flx/flx) MZ B-cell–deficient (MZ-KO) recipients.31 OTII × Thy1.1 donors and S1PR1TSS recipients were generous gifts from Jacob Kohlmeir (Emory University) and Jason Cyster (University of California San Francisco),32 respectively. Transgenic HOD donors were maintained as outlined previously.33,34 A combination of 8- to 12-week-old male and female mice was used. All animals were housed and bred in cages at the Emory University Department of Animal Resources facilities, and all experiments were performed under animal protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University.

RBC isolation, storage, labeling, transfusion, and staining

RBCs were collected from HOD mice into 1:8 ACD and washed in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Packed RBCs were adjusted to 75% hematocrit in 14% CPDA-1 and stored at 4°C for 7 to 10 days. Each mouse was transfused with 50 μL of packed HOD RBCs diluted in PBS to 300 μL total volume via lateral tail vein injection.33-36 For visualization during confocal microscopy, HOD RBCs were labeled with CellTracker 3, 39-dihexadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate (DiO; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), as done previously.31 HEL, OVA, and Duffy antigen levels were detected on HOD RBCs posttransfusion as previously outlined.37 HEL and OVA coupling to sheep RBCs was prepared as outlined previously.38

Confocal microscopy

B6 MZ B-cell–depleted, FO B-cell–depleted, PBS-treated, or isotype control (IC)-treated recipients were transfused with PBS or DiO-labeled HOD RBCs, followed by splenic harvest at various time points after transfusion, as indicated. Spleens were frozen, sectioned, and fixed as previously described.31,39 Sections were stained with Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse IgD and PE anti-mouse CD1d and mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). A Leica SP8 multiphoton confocal microscope was used to capture images that were analyzed using Leica Application Suite software.

Cellular depletion and analysis of B cells

To deplete MZ B cells, B6 recipients received monoclonal anti-mouse CD11a antibody (clone M17/4) and monoclonal anti-mouse CD49d antibody (clone PS/2; both from Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH) 4 and 2 days prior to RBC transfusion.39-41 For CD4 T-cell depletion, recipients received monoclonal anti-mouse CD4-depleting antibody (clone GK1.5; Bio X Cell) 4 and 2 days prior to transfusion.31 FO B-cell depletion or total B-cell depletion was achieved through administration of monoclonal anti-mouse CD20 IgG1-depleting antibody (clone 18B12; Biogen Idec, Cambridge, MA) or monoclonal anti-mouse CD20 IgG2a-depleting antibody (clone SA271G2; BioLegend, San Diego, CA), respectively, 14 days prior to transfusion, as outlined previously.42 To control for possible nonspecific effects of antibody treatment, recipients received IC antibodies: Rat IgG2b and Rat IgG2a (MZ B-cell depletion, clones LTF2 and 2A3; Bio X Cell); Rat IgG2b (CD4 T-cell depletion, clone LTF2; Bio X Cell); mouse IgG1 (FO B-cell depletion, clone MOPC-21; Biogen Idec), or mouse IgG2a (total B-cell depletion, clone eBM2a; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Efficacy of CD4 T-cell depletion was initially assessed in peripheral blood samples with FITC rat anti-mouse CD3ε, PE rat anti-mouse CD8α, and APC rat anti-mouse CD4 (clone RM-45). Depletion of MZ B cells and FO B cells was assessed in representative mice by staining splenocytes with FITC rat anti-mouse CD45R/B220, PE rat anti-mouse CD23, and APC rat anti-mouse CD21. Antigen-specific B cells were detected by staining cells with Zombie Yellow Fixable Viability Dye, PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD23 (clone B3B4), BV650 anti-mouse CD3 (clone 17A2), BV750 anti-mouse B220 (clone RA3-6B2), PE anti-mouse CD95 (clone SA367H8), APC-Cy7 anti-mouse CD21 (clone 7E9), Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse GL7, and each HEL tetramer. For HEL tetramer development, HEL was biotinylated using EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then purified using 7-kDa molecular-weight cutoff Zeba Spin Desalting Columns (Thermo Fisher Scientific). BV421- or PE-Cy5–labeled streptavidin was added to biotinylated HEL. Samples were run on a BD FACSCalibur or LSR II flow cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software.

Analysis of CD4 T-cell proliferation and activation

Splenocytes from OTII × Thy1.1 donors were isolated and labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) using a CellTrace CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which was confirmed by flow cytometry. A total of 1 × 106 CFSE-labeled OTII × Thy1.1 splenocytes were adoptively transferred into each recipient via lateral tail vein injection 24 hours prior to PBS or HOD RBC transfusion. Proliferation and activation of Thy1.1 CD4 T cells were assessed by staining splenocytes with Brilliant Violet 786 anti-mouse CD3, V500 anti-mouse CD4, APC anti-mouse Thy1.1, PE CF594 anti-mouse CD62L, and Alexa Fluor 700 anti-mouse CD44. Samples were run on a BD LSR II flow cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software.

Seroanalysis for anti-HOD antibodies

Serum was collected from transfused recipients on days 3, 5, 7, 14, and 21 after transfusion. The presence of anti-HOD antibodies in serum was evaluated through indirect immunofluorescent staining, as described previously.31,35,43 Briefly, serum was combined with packed HOD or B6 RBCs, followed by incubation with APC anti-mouse IgG and FITC anti-mouse IgM. IgG subclasses were identified using PE anti-mouse IgG1, Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG2b, PerCP anti-mouse IgG3, and PE anti-mouse IgG2c. The presence of antigen-specific antibody subsets was measured using a 4-color BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software. Anti-HEL antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed as described previously.44

Statistics

A nonparametric unpaired Student t test or 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with a post hoc Tukey multiple-comparisons test was performed to determine the significance of results. Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

MZ B cells regulate RBC alloimmunization

Although a variety of immune populations may regulate alloantibody development following RBC transfusion,34,45-49 previous studies suggest a potential role for the spleen in RBC-induced alloantibody formation.50,51 As a result, we first sought to determine whether the spleen regulates anti-HOD antibody formation. To accomplish this, HOD− B6 recipients were splenectomized or sham operated 2 weeks prior to HOD RBC transfusion, followed by evaluation of alloantibody formation (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site). Although IgM (supplemental Figure 1A) and IgG (supplemental Figure 1A) anti-HOD antibodies could be readily detected in sham-operated recipients, anti-HOD antibodies were virtually undetectable in splenectomized recipients. Taken together, these data suggest that the spleen regulates the immune response to HOD RBCs following transfusion.

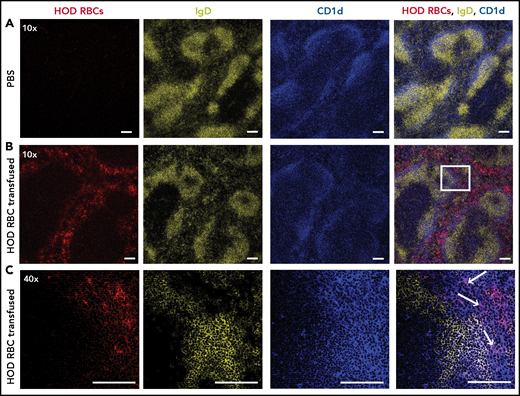

We next sought to determine whether HOD RBCs associate with key immune players in the spleen following transfusion. To accomplish this, PBS (Figure 1A) or DiO-labeled HOD RBCs (Figure 1B) were transfused into recipients, followed by splenic harvest and staining of MZ B cells and FO B cells, as described previously.52-54 Most of the transfused HOD RBCs were detected in the splenic red pulp, with virtually no RBCs detected within areas of the white pulp outlined by the rim of MZ B cells. However, some of the transfused HOD RBCs localized to the marginal sinus that resides between the white pulp and red pulp (Figure 1B). At higher magnification, some HOD RBCs colocalized with MZ B cells within the marginal sinus (Figure 1C). These results suggest that MZ B cells may interact with HOD RBCs following transfusion and, therefore, may be involved in initiating the immune response to HOD.

HOD RBCs colocalize with MZ B cells within the marginal sinus of the spleen following transfusion. HOD RBCs were isolated and stained with DiO, resulting in a fluorescently distinct population. (A-B) PBS (A) or DiO-labeled HOD RBCs (red) (B) were injected into HOD− B6 recipients, followed by splenic harvest 24 hours after transfusion and immunofluorescent staining of FO B cells (IgD; yellow) and MZ B cells (CD1d; blue). Samples were analyzed using a Leica SP8 multiphoton confocal microscope with a ×10 (A-B) or ×40 (C) objective. The white box in panel B is magnified in panel C. White arrows indicate examples of colocalization of transfused HOD RBCs with MZ B cells. Scale bars, 100 μm. Representative data are shown from experiments reproduced 2 or 3 times, with 3 mice per group per experiment.

HOD RBCs colocalize with MZ B cells within the marginal sinus of the spleen following transfusion. HOD RBCs were isolated and stained with DiO, resulting in a fluorescently distinct population. (A-B) PBS (A) or DiO-labeled HOD RBCs (red) (B) were injected into HOD− B6 recipients, followed by splenic harvest 24 hours after transfusion and immunofluorescent staining of FO B cells (IgD; yellow) and MZ B cells (CD1d; blue). Samples were analyzed using a Leica SP8 multiphoton confocal microscope with a ×10 (A-B) or ×40 (C) objective. The white box in panel B is magnified in panel C. White arrows indicate examples of colocalization of transfused HOD RBCs with MZ B cells. Scale bars, 100 μm. Representative data are shown from experiments reproduced 2 or 3 times, with 3 mice per group per experiment.

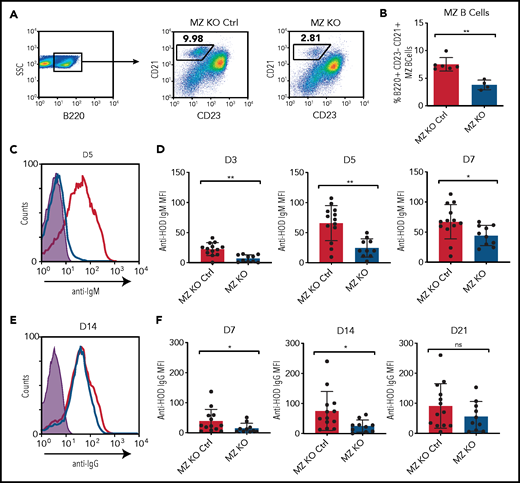

To examine the potential role of MZ B cells in the development of alloantibodies, we first took advantage of the involvement of Notch2 in MZ B-cell development.25,55 Because Notch2 can influence the behavior of other immune populations,56,57 to isolate Notch2 deficiency to B cells, we crossed CD19cre/+ × Notch2flx/flx mice to genetically reduce MZ B cells.31 We first examined B-cell populations isolated from MZ-KO mice to determine whether these recipients are specifically deficient in MZ B cells. Consistent with previous results, MZ-KO mice, but not CD19+/+ × Notch2flx/flx littermate controls, exhibited significantly reduced MZ B-cell numbers (Figure 2A-B). To determine whether MZ-KO recipients exhibit any differences from littermate controls with regard to anti-HOD antibody formation, we transfused recipients with HOD RBCs, followed by examination of anti-HOD antibody formation. MZ-KO recipients displayed an attenuated anti-HOD IgM antibody response (Figure 2C-D) and delayed IgG formation (Figure 2E-F), suggesting that MZ B cells may at least, in part, regulate the initial development of anti-HOD antibody formation.

MZ B cells play a role in anti-HOD alloantibody formation. (A-B) Gating strategy (A) and quantification (B) of the percentage of B220+CD23−CD21hi MZ B cells in splenocytes obtained from MZ-KO and CD19+/+ × Notch2flx/flx (MZ-KO Ctrl) mice. (C-D) Representative line graph (C) and quantification (D) of anti-HOD IgM alloantibody formation in MZ B-cell–KO mice (blue) compared with MZ B-cell–KO littermate control mice (red) following HOD RBC transfusion. (E-F) Representative line graph (E) and quantification (F) of anti-HOD IgG alloantibody formation in MZ B-cell–KO mice (blue) compared with MZ B-cell–KO littermate control mice (red) following HOD RBC transfusion.

MZ B cells play a role in anti-HOD alloantibody formation. (A-B) Gating strategy (A) and quantification (B) of the percentage of B220+CD23−CD21hi MZ B cells in splenocytes obtained from MZ-KO and CD19+/+ × Notch2flx/flx (MZ-KO Ctrl) mice. (C-D) Representative line graph (C) and quantification (D) of anti-HOD IgM alloantibody formation in MZ B-cell–KO mice (blue) compared with MZ B-cell–KO littermate control mice (red) following HOD RBC transfusion. (E-F) Representative line graph (E) and quantification (F) of anti-HOD IgG alloantibody formation in MZ B-cell–KO mice (blue) compared with MZ B-cell–KO littermate control mice (red) following HOD RBC transfusion.

The delayed anti-HOD response observed in MZ-KO recipients suggests that MZ B cells may be involved in recognizing and responding to HOD RBCs, but that additional immune pathways may possess the ability to engage the antigen at later time points. However, although MZ-KO recipients are deficient in MZ B cells, ∼20% to 30% of B220+CD21hiCD23lo/− MZ B cells remain, suggesting that residual MZ B cells may be capable of supporting a delayed, but detectable, immune response to HOD RBCs. To control for this possibility, we used an alternative strategy of MZ B-cell depletion by injecting recipients with a mixture of anti-CD11a and anti-mouse CD49d antibodies, as outlined previously.31,39 Importantly, this approach resulted in complete removal of MZ B cells from the spleen (Figure 2G-H). To determine the impact of MZ B-cell depletion on HOD alloimmunization, MZ B-cell–depleted or IC recipients received HOD RBCs, followed by evaluation for anti-HOD antibody formation. Depletion of MZ B cells prior to HOD RBC transfusion prevented detectable anti-HOD antibody formation (Figure 2I-L). Although IgG anti-HEL antibody detection using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to evaluate alloantibody formation in these models similarly failed to detect anti-IgG antibodies in MZ B cell–depleted recipients,44,58 total IgG levels remained similar (supplemental Figure 2). Failure to detect IgG anti-HOD antibodies did not appear to reflect an isotype-specific defect in IgG evaluation,59 because anti-HOD IgG isotypes were likewise significantly decreased in MZ B-cell–depleted recipients (supplemental Figure 2). Taken together, these results suggest that MZ B cells may play a role in the development of anti-HOD antibodies following HOD RBC transfusion.

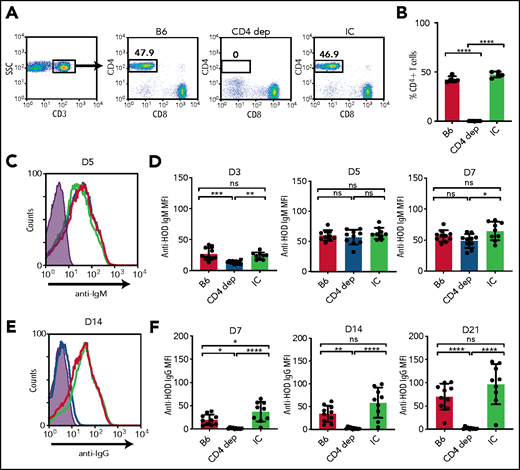

HOD RBC–induced IgG, but not IgM, requires CD4 T cells

MZ B cells possess the capacity to produce IgM antibodies after engagement of target antigen, followed by orchestration of downstream immune responses, including facilitation of the FO B-cell response to encountered antigen.23 This facilitation is believed to occur through activation of CD4 T cells and/or trafficking of antigen to the B-cell follicle.23 However, whether IgM antibodies form in the absence of CD4 T-cell help and, therefore, are likely derived from MZ B cells remains unknown. To determine whether CD4 T cells are required or in any way influence IgM anti-HOD alloantibody formation, we depleted CD4 T cells prior to HOD RBC transfusion (Figure 3A-B). HOD RBC transfusion induced similar levels of IgM anti-HOD antibody formation in the presence or absence of CD4 T cells (Figure 3C-D). In contrast, IgG anti-HOD antibody formation was virtually undetectable following HOD RBC transfusion into CD4 T-cell–depleted recipients (Figure 3E-F). Similar to MZ B-cell depletion, the inability to detect IgG antibody formation did not appear to reflect an isotype-specific defect in detection (supplemental Figure 2). Taken together, these results suggest that, although MZ B cells may be required for IgM anti-HOD antibody formation, IgG antibody formation appears to require MZ B cells and CD4 T cells.

CD4 T cells are required for anti-HOD IgG alloantibody formation. (A-B) Gating strategy (A) and quantification (B) of the percentage of CD3+CD4+CD8− CD4 T cells in splenocytes obtained from B6 mice that received PBS (B6), CD4-depleting antibody (CD4 dep), or IC antibody. (C-D) Representative line graph (C) and quantification (D) of anti-HOD IgM alloantibody formation in CD4 T-cell–depleted mice (blue) compared with B6 control mice (red) and IC mice (green) following HOD RBC transfusion. (E-F) Representative line graph (E) and quantification (F) of anti-HOD IgG alloantibody formation in CD4 T-cell–depleted mice (blue) compared with B6 control mice (red) and IC mice (green) following HOD RBC transfusion. Error bars represent standard deviation; results are representative of 2 or 3 independent experiments with ≥5 mice per group. ****P < .0001, ***P < .0002, **P < .006, *P < .02; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. D3, day 3; D5, day 5; D7, day 7; D14, day 14; D21, day 21; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

CD4 T cells are required for anti-HOD IgG alloantibody formation. (A-B) Gating strategy (A) and quantification (B) of the percentage of CD3+CD4+CD8− CD4 T cells in splenocytes obtained from B6 mice that received PBS (B6), CD4-depleting antibody (CD4 dep), or IC antibody. (C-D) Representative line graph (C) and quantification (D) of anti-HOD IgM alloantibody formation in CD4 T-cell–depleted mice (blue) compared with B6 control mice (red) and IC mice (green) following HOD RBC transfusion. (E-F) Representative line graph (E) and quantification (F) of anti-HOD IgG alloantibody formation in CD4 T-cell–depleted mice (blue) compared with B6 control mice (red) and IC mice (green) following HOD RBC transfusion. Error bars represent standard deviation; results are representative of 2 or 3 independent experiments with ≥5 mice per group. ****P < .0001, ***P < .0002, **P < .006, *P < .02; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. D3, day 3; D5, day 5; D7, day 7; D14, day 14; D21, day 21; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

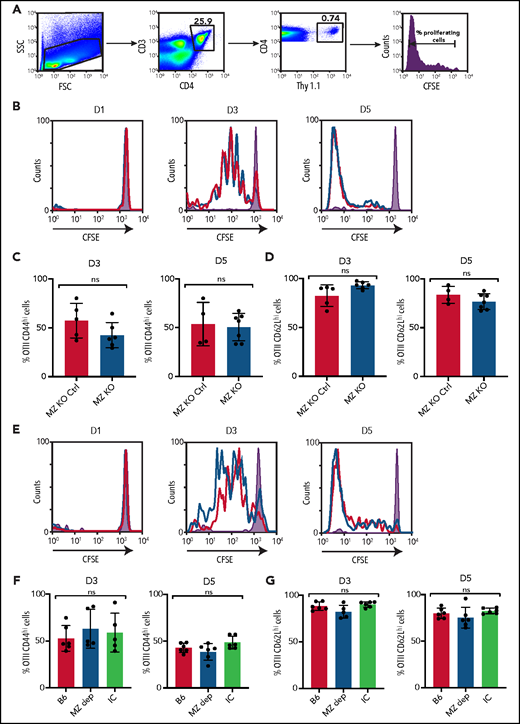

MZ B cells are not required for CD4 T-cell activation or trafficking of antigen to the follicle

Given the impact of MZ B-cell removal on the development of IgM and IgG anti-HOD antibody formation, coupled with the dependence of IgG anti-HOD antibody formation on CD4 T cells, we next sought to determine whether MZ B cells directly activate CD4 T cells, as recently suggested following exposure to other antigens.23,60 To test this, we examined the CD4 T-cell antigen-specific response to HOD RBCs through adoptive transfer of CD4 T cells specific for the OVA portion of HOD (OTII T cells)61 (Figure 4A), in the presence or absence of MZ B cells. OTII T-cell proliferation did not change following HOD RBC transfusion into MZ B-cell–deficient recipients (Figure 4B). Similar to proliferation, general changes in CD4 T-cell activation did not appear to be impacted by the absence of MZ B cells (Figure 4C-D). We next depleted B6 recipients of MZ B cells prior to OTII T-cell transfer and HOD RBC transfusion. Similarly, depletion of MZ B cells failed to impact OTII T-cell proliferation and activation (Figure 4E-G). Taken together, these results suggest that CD4 T-cell activation following HOD RBC transfusion can occur through an MZ B-cell–independent process.

HOD-specific CD4 T-cell activation is not dependent on MZ B cells. (A) Gating strategy and line graph showing proliferation, as measured by CFSE dilution, of CFSE-labeled CD4+Thy1.1+ OTII T cells obtained from recipient splenocytes 5 days following HOD RBC transfusion. (B) MZ-KO mice (blue) and MZ B-cell littermate control (MZ-KO Ctrl) recipients (red) received transfusion with HOD RBCs, followed by examination of splenocytes for OTII T-cell proliferation on days 1 (D1), 3 (D3), and 5 (D5); representative line graphs are shown. (C-D) OTII T cells were stained for activation markers, including CD44 (C) and CD62L (D). (E-G) B6 control recipients received HOD RBC transfusion alone (B6), MZ B-cell–depleting antibodies followed by HOD RBC transfusion (MZ B dep), or IC antibodies followed by HOD RBC transfusion (IC). Splenocytes were examined on D1, D3, and D5 for OTII T-cell proliferation; representative line graphs are shown (E). OTII T cells from these groups were stained for activation markers, including CD44 (F) and CD62L (G). Shaded graphs represent CFSE proliferation in a control mouse that received CFSE-labeled OTII T cells but did not receive HOD RBC transfusion. The red line indicates MZ B-cell–depleted mice, and the black line represents B6 control group following HOD RBC transfusion. Error bars represent standard deviation; results are a combination of 2 independent experiments with ≥3 mice per time point per group. Statistical significance was assessed using a nonparametric unpaired Student t test or 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. ns, not significant.

HOD-specific CD4 T-cell activation is not dependent on MZ B cells. (A) Gating strategy and line graph showing proliferation, as measured by CFSE dilution, of CFSE-labeled CD4+Thy1.1+ OTII T cells obtained from recipient splenocytes 5 days following HOD RBC transfusion. (B) MZ-KO mice (blue) and MZ B-cell littermate control (MZ-KO Ctrl) recipients (red) received transfusion with HOD RBCs, followed by examination of splenocytes for OTII T-cell proliferation on days 1 (D1), 3 (D3), and 5 (D5); representative line graphs are shown. (C-D) OTII T cells were stained for activation markers, including CD44 (C) and CD62L (D). (E-G) B6 control recipients received HOD RBC transfusion alone (B6), MZ B-cell–depleting antibodies followed by HOD RBC transfusion (MZ B dep), or IC antibodies followed by HOD RBC transfusion (IC). Splenocytes were examined on D1, D3, and D5 for OTII T-cell proliferation; representative line graphs are shown (E). OTII T cells from these groups were stained for activation markers, including CD44 (F) and CD62L (G). Shaded graphs represent CFSE proliferation in a control mouse that received CFSE-labeled OTII T cells but did not receive HOD RBC transfusion. The red line indicates MZ B-cell–depleted mice, and the black line represents B6 control group following HOD RBC transfusion. Error bars represent standard deviation; results are a combination of 2 independent experiments with ≥3 mice per time point per group. Statistical significance was assessed using a nonparametric unpaired Student t test or 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. ns, not significant.

The ability of MZ B cells to traffic antigen to B cell follicles,23,60,62 coupled with the lack of a requirement for MZ B cells in CD4 T-cell activation following HOD exposure, suggests that MZ B cells may instead be required to traffic the HOD antigen to the B-cell follicle. To test this, we first examined HOD RBC localization over time. HOD RBCs continued to colocalize with MZ B cells up to 14 days following transfusion with little evidence of HOD RBC movement into the B-cell follicle (Figure 5A). Consistent with this, transfusion of HOD RBCs into S1PR1TSS-knockout (KO) recipients, which possess a genetic deficiency that prevents MZ B-cell migration to the B-cell follicle and, thus, inhibits their ability to traffic antigen,32 resulted in IgM and IgG anti-HOD antibody formation that was similar between S1PR1TSS-KO recipients and littermate controls (supplemental Figure 3). It remained possible that, in some way, MZ B-cell trafficking influences the subclass distribution of IgG antibody formation by influencing the ultimate outcome of CD4 T-cell interactions with FO B cells.63 However, no differences in IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c, or IgG3 anti-HOD antibody levels were observed following HOD RBC transfusion into S1PR1TSS-KO or littermate control recipients (supplemental Figure 3), strongly suggesting that the overall IgG response to HOD occurs independently of MZ B-cell–mediated HOD RBC trafficking.

HOD RBCs remain detectable in the marginal sinus despite losing surface antigen over time. HOD RBCs were isolated and stained with DiO, resulting in a fluorescently distinct population. (A) PBS or DiO-labeled HOD RBCs (red) were injected into HOD− B6 recipients, followed by splenic harvest at the indicated time points after transfusion and immunofluorescent staining of FO B cells (IgD; yellow) and MZ B cells (CD1d; blue). Samples were analyzed using a Leica SP8 multiphoton confocal microscope with a ×10 or ×40 objective . Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Quantitation of HEL, OVA, and Duffy antigen levels detected by flow cytometry at the time points indicated posttransfusion. ****P < .0001, ***P < .0003 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. ns, not significant.

HOD RBCs remain detectable in the marginal sinus despite losing surface antigen over time. HOD RBCs were isolated and stained with DiO, resulting in a fluorescently distinct population. (A) PBS or DiO-labeled HOD RBCs (red) were injected into HOD− B6 recipients, followed by splenic harvest at the indicated time points after transfusion and immunofluorescent staining of FO B cells (IgD; yellow) and MZ B cells (CD1d; blue). Samples were analyzed using a Leica SP8 multiphoton confocal microscope with a ×10 or ×40 objective . Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Quantitation of HEL, OVA, and Duffy antigen levels detected by flow cytometry at the time points indicated posttransfusion. ****P < .0001, ***P < .0003 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. ns, not significant.

Given the continued localization of HOD RBCs in the marginal sinus, we next sought to examine whether antigen levels on HOD RBCs likewise persist, even at later time points; previous studies suggested that antigen levels can decline on transfused RBCs over time.33,37 Indeed, HEL and OVA antigen levels declined over time, exhibiting significant decreases within 5 days of transfusion. In contrast, the Duffy antigen failed to change 14 days posttransfusion (Figure 5B), strongly suggesting that the availability of the HEL and OVA antigens on the RBC surface change over time. Despite impacting antibody formation, MZ B-cell depletion failed to influence HOD RBC localization (supplemental Figure 4), strongly suggesting that other cellular constituents within the marginal sinus may be responsible for HOD RBC localization.

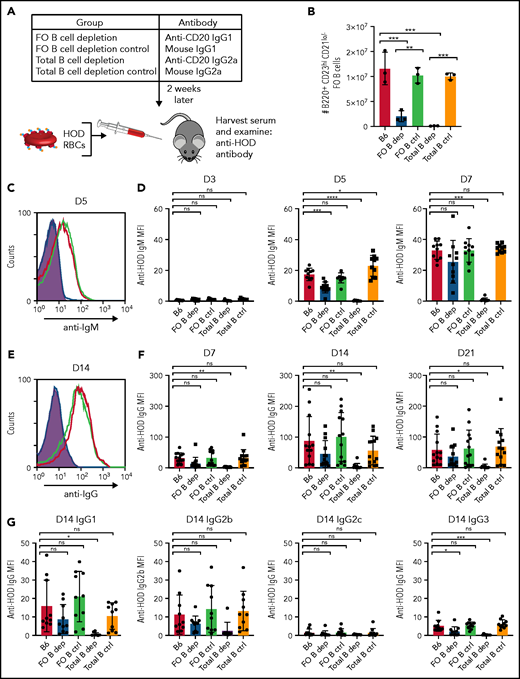

HOD RBCs can induce alloantibody formation through an FO B-cell–independent pathway

Because MZ B-cell–mediated antigen trafficking or MZ B-cell–dependent CD4 T-cell activation does not appear to be required for HOD RBC-induced antibody formation, we next examined the involvement of FO B cells. To accomplish this, we specifically depleted FO B cells prior to HOD RBC transfusion as described previously.31 For comparison, total B cells were depleted in additional recipients prior to transfusion (Figure 6A-B). FO B-cell depletion resulted in a slightly attenuated IgM anti-HOD antibody response (Figure 6C-D), with no statistically significant difference in the development of IgG anti-HOD antibodies (Figure 6E-F). In contrast, total B-cell depletion completely prevented IgM and IgG anti-HOD antibody formation following HOD RBC transfusion (Figure 6C-F). In addition, there was no observed difference in the subclass distribution of anti-HOD IgG antibodies between control and FO B-cell–depleted recipients (Figure 6G). Similar to MZ B-cell depletion, FO B-cell depletion failed to significantly impact HOD RBC localization (supplemental Figure 4), suggesting that initial localization of HOD RBCs also occurs independently of FO B cells. Furthermore, although MZ B cells began to repopulate the marginal zone, FO B cells remained depleted (supplemental Figure 5).

HOD alloantibody production occurs independently of FO B cells. (A) General experimental design. B6 recipients received FO B-cell–depleting, total B-cell–depleting, or IC antibodies, followed by HOD RBC transfusion 2 weeks later. Serum was collected 3, 5, 7, 14, and 21 days following transfusion and examined for anti-HOD antibodies by flow cytometric analysis. (B) Quantification of absolute number of B220+CD23hiCD21lo FO B cells in splenocytes of B6 recipients that received PBS (B6), FO B-cell–depleting antibody anti-CD20 IgG1 (FO B dep), mouse IgG1 IC antibody (FO B ctrl), B-cell–depleting antibody anti-CD20 IgG2a (Total B dep), or mouse IgG2a IC antibody (Total B ctrl). (C-D) Representative line graph (C) and quantification (D) of anti-HOD IgM alloantibody formation in FO B-cell–depleted recipients (blue) compared with B6 control (red) and total B-cell–depleted (purple) recipients following HOD RBC transfusion. (E-F) Representative line graph (E) and quantification (F) of anti-HOD IgG alloantibody formation in FO B-cell–depleted recipients (blue) compared with B6 control (red) and total B-cell–depleted (purple) recipients following HOD RBC transfusion. (G) Anti-HOD IgG antibody subclass analysis on plasma collected 14 days after HOD RBC transfusion. Error bars represent standard deviation; results are representative of 2 or 3 independent experiments with ≥5 mice per group. ****P < .0001, ***P < .0004, **P < .009, *P < .04; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. D3, day 3; D5, day 5; D7, day 7; D14, day 14; D21, day 21; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

HOD alloantibody production occurs independently of FO B cells. (A) General experimental design. B6 recipients received FO B-cell–depleting, total B-cell–depleting, or IC antibodies, followed by HOD RBC transfusion 2 weeks later. Serum was collected 3, 5, 7, 14, and 21 days following transfusion and examined for anti-HOD antibodies by flow cytometric analysis. (B) Quantification of absolute number of B220+CD23hiCD21lo FO B cells in splenocytes of B6 recipients that received PBS (B6), FO B-cell–depleting antibody anti-CD20 IgG1 (FO B dep), mouse IgG1 IC antibody (FO B ctrl), B-cell–depleting antibody anti-CD20 IgG2a (Total B dep), or mouse IgG2a IC antibody (Total B ctrl). (C-D) Representative line graph (C) and quantification (D) of anti-HOD IgM alloantibody formation in FO B-cell–depleted recipients (blue) compared with B6 control (red) and total B-cell–depleted (purple) recipients following HOD RBC transfusion. (E-F) Representative line graph (E) and quantification (F) of anti-HOD IgG alloantibody formation in FO B-cell–depleted recipients (blue) compared with B6 control (red) and total B-cell–depleted (purple) recipients following HOD RBC transfusion. (G) Anti-HOD IgG antibody subclass analysis on plasma collected 14 days after HOD RBC transfusion. Error bars represent standard deviation; results are representative of 2 or 3 independent experiments with ≥5 mice per group. ****P < .0001, ***P < .0004, **P < .009, *P < .04; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. D3, day 3; D5, day 5; D7, day 7; D14, day 14; D21, day 21; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

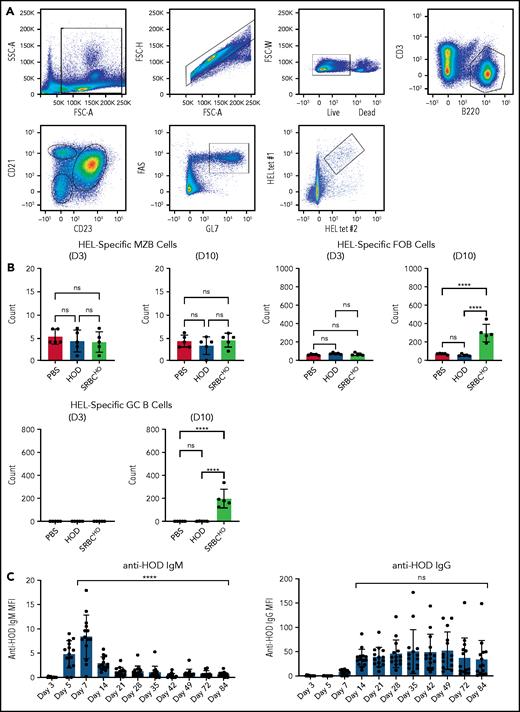

The ability of HOD RBCs to induce antibody formation in the absence of FO B cells suggests that HOD RBC-induced antibodies occur through a B-cell follicle and GC B-cell–independent process. To test this, we next evaluated the frequency of HEL antigen-specific MZ, FO, and GC B cells following HOD RBC transfusion (Figure 7A); as a control we evaluated sheep RBCs covalently coupled with HEL and OVA (SRBCHO), because previous reports suggested that sheep RBCs can induce a robust GC response.64 Although no differences in HEL-specific MZ B cells were observed, regardless of transfusion, increases in HEL-specific FO B cells were observed following SRBCHO, but not HOD, RBC transfusion (Figure 7B). Similarly, although significant increases in HEL-specific GC B cells were detected following SRBCHO transfusion, HOD RBC transfusion failed to increase HEL-specific GC B-cell numbers (Figure 7B). Interestingly, despite failing to induce detectable antigen-specific GC B cells, HOD RBC–induced antibodies could persist for several months following transfusion (Figure 7C). Taken together, these results suggest that HOD RBCs possess the ability to induce IgG anti-HOD antibodies in a GC-independent manner.

HOD alloantibody production occurs in the absence of antigen-specific GC B cells. (A) Representative dot plots used to detect MZ B cells, FO B cells, and GC B cells. (B) Quantification of HEL antigen–specific MZ B cells, FO B cells, or GC B cells on day 3 or 10 following PBS injection or transfusion with HOD RBCs or SRBCHO. (C) Evaluation of IgM and IgG anti-HOD antibody formation following HOD RBC transfusion at the times indicated posttransfusion. Error bars represent standard deviation; results are representative of 2 independent experiments. ****P < .0001; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. D3, day 3; D10, day 10; ns, not significant.

HOD alloantibody production occurs in the absence of antigen-specific GC B cells. (A) Representative dot plots used to detect MZ B cells, FO B cells, and GC B cells. (B) Quantification of HEL antigen–specific MZ B cells, FO B cells, or GC B cells on day 3 or 10 following PBS injection or transfusion with HOD RBCs or SRBCHO. (C) Evaluation of IgM and IgG anti-HOD antibody formation following HOD RBC transfusion at the times indicated posttransfusion. Error bars represent standard deviation; results are representative of 2 independent experiments. ****P < .0001; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. D3, day 3; D10, day 10; ns, not significant.

Discussion

Transfusion-dependent patients are particularly vulnerable to the adverse consequences of RBC alloimmunization. Although matching alloantigens prior to transfusion holds significant promise in preventing alloimmunization events from occurring,65 logistical challenges in complex health care delivery environments continue to create significant hurdles in the effective delivery of appropriately matched RBCs for patients at risk for alloantibody-related complications. As a result, complementary strategies aimed at actively inhibiting alloimmunization may also aid in efforts to reduce complication rates due to RBC alloimmunization. However, for immune targeting approaches to be realized, a fundamental understanding of the immune pathways engaged by RBC alloantigens is needed. Prior studies examining RBC alloimmunization in patients have demonstrated that alloimmunization can occur through a classic GC-dependent process, including the involvement of FO B cells.66,67 These studies suggest that targeting these immune populations may be useful when seeking to prevent alloimmunization from occurring. The present results suggest that, in addition to these previously described approaches, FO B-cell–independent pathways may exist that could benefit from considerations used in future studies to prevent or reduce RBC alloimmunization. Recent studies have suggested that extrafollicular B-cell responses may also play a key role in the humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2,68,69 possibly contributing to the rapid antibody production and class switching observed in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.70 Similar to some of the HOD RBC–transfused mice observed in the present study, anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies can wane within a few months of infection.71,72

Because defining key early immune determinants required for alloantibody formation can be challenging clinically, several attempts have been made to generate murine models of RBC alloimmunization that are capable of leveraging a variety of immunological tools to define key early events in this pathway. The 2 most commonly used models use the KEL antigen, one of the most common antigens implicated in hemolytic transfusion reactions and hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn,73,74 and the HOD antigen,45 described in the present work. Previous studies demonstrated that KEL RBCs are capable of inducing alloantibody formation through a CD4 T-cell–independent pathway.31,33 In contrast, HOD RBCs induce IgG anti-HOD antibody formation through a CD4 T-cell–dependent pathway. Consistent with these findings, although some alloimmunization events appear to be associated with HLA and, therefore, are likely CD4 T-cell dependent,75-84 other studies failed to observe similar correlations between HLA status and alloantibody formation,85 suggesting that CD4 T-cell–independent pathways of RBC alloimmunization may also exist. Results obtained using these model systems suggest that distinct RBC alloantigens may possess the ability to induce IgG alloantibodies through unique immune pathways, including CD4 T-cell–dependent or -independent processes, illustrating the importance of identifying common pathways when seeking to prevent alloimmunization following possible exposure to many distinct alloantigens after RBC transfusion.

Despite differences in the requirement of CD4 T cells following KEL or HOD RBC transfusion, both antigens appear to engage similar initiating immune players. HOD and KEL RBCs localize with MZ B cells shortly after transfusion, and genetic deletion or depletion of MZ B cells reduces IgM and IgG alloantibody formation following exposure to either antigen.31 Although these results suggest that MZ B cells serve as key initiators of KEL and HOD alloantibody formation, the different requirements for CD4 T cells demonstrate that these antigens possess the ability to induce distinct downstream immune pathways. Differences in the ability of IgM antibodies to fix complement following engagement of HOD or KEL during the early immune response or other features of each antigen may regulate, in part, distinct downstream pathways.86,87 The requirement of both MZ B cells and CD4 T cells for HOD RBC–induced alloantibody formation, coupled with prior data demonstrating that MZ B cells can be potent activators of CD4 T cells and critical transporters of antigen to the B-cell follicle, initially suggested that MZ B cells coordinate with CD4 T cells to facilitate a GC reaction. However, genetic deletion or depletion of MZ B cells failed to impact CD4 T-cell proliferation following HOD RBC transfusion, suggesting that MZ B cells are not required for CD4 T-cell activation. Consistent with this, previous studies demonstrated that 33D1+ bridging channel dendritic cells are important in the activation of CD4 T-cell activation following HOD RBC transfusion,88 suggesting that MZ B cells may instead traffic antigen to the B-cell follicle. However, MZ B-cell trafficking–deficient recipients exhibited normal anti-HOD antibody formation following HOD RBC transfusion, suggesting that MZ B-cell trafficking is not required for HOD RBC–induced alloantibody formation. Consistent with this, HOD RBCs retained the ability to induce anti-HOD antibodies following transfusion into recipients in the absence of FO B cells. It should be noted that FO B-cell depletion did result in a blunted IgM response and a trend toward reduced early IgG formation against HOD RBCs. As a result, these data do not exclude the possibility that, when present, FO B cells contribute to the development of anti-HOD antibodies. Overall, the results of this study suggest that MZ B cells alone may mediate a CD4 T-cell–dependent extrafollicular IgG response to the HOD antigen.

Consistent with the ability of HOD RBCs to induce antibody formation independent of FO B cells, virtually no detectable change in HEL-specific GC B cells occurred following HOD RBC transfusion, suggesting that if FO B cells are engaged, this involvement likely occurs independently of a GC response. Because early studies suggest that the GC response is critical for long-lived antibody formation,89 the lack of a statistically significant decrease in overall alloantibody levels during the first 12 weeks following HOD RBC transfusion was unexpected. However, more recent studies suggest that extrafollicular B-cell responses may produce long-lived antibody-secreting cells.69 It is important to note that close analysis of long-term antibody production did reveal that some individual mice experienced a decline in anti-HOD antibody formation over time, suggesting that the durability of anti-HOD antibody formation can be variable. Because RBC transfusion in general would be predicted to be a relatively weak immune stimulus,90 subtle differences in environmental factors or other variables altogether may influence the overall magnitude and maintenance of antibody formation. Future studies will certainly be needed to explore these and other possibilities.

This study is certainly not without limitations. Differences exist between human and mouse splenic architecture,91 suggesting that the outcomes of the present study may be influenced, in part, by unique characteristics of these model systems. Some patients with transfusion-dependent conditions like SCD may be considered “functionally asplenic,” suggesting that other compartments may be involved or even be entirely responsible for alloimmunization in this setting. Conflicting data exist regarding whether the spleen may impact alloimmunization.51,92,93 However, studies examining the possible contribution of the spleen in alloimmunization clinically can be challenging to interpret, because it can be especially difficult to pinpoint whether initial alloantigen exposure occurred prior to or following the development of functional asplenia,94 especially in chronically transfused individuals. Because alloantibodies can also evanesce prior to detection,95 early exposure prior to compromised or even absent spleen function may induce immune priming events that facilitate subsequent alloantibody formation independent of the spleen.94 Furthermore, recent studies propose that some splenic function is retained in SCD96,97 and that hydroxyurea therapy or RBC transfusion can increase this function,98-100 raising the possibility that the spleen, although certainly altered, possesses residual function and plays a direct role in alloimmunization, even in this patient population.100-105 In this way, it is possible that transfusion may expose patients to alloantigens, as well as enhance splenic involvement in alloantibody formation.100-105 Several earlier studies likewise suggest a role for the spleen in human anti-RBC antibody formation.50,51 Similar to the spleen, although MZ B cells may certainly differ between patients and mice, prior studies indicate that human MZ B cells may also trap and immediately respond to encountered antigen,25-27,62 suggesting that these cells may be uniquely poised to initiate RBC alloantibody formation. Because MZ B cells exhibit a lower activation threshold than do FO B cells,23 the ability of MZ B cells to mediate RBC alloantibody formation may explain, in part, why individuals can respond to RBC alloantigens in the absence of any known adjuvant. Furthermore, because peripheral antigen engagement can impact MZ B-cell differentiation, which can influence responsiveness to antigen,26,106 it is possible that MZ B-cell repopulation following initial depletion in the face of ongoing circulating RBC alloantigen impacts their ability to respond to circulating HOD RBCs. Either way, the results of the present study suggest that even transient depletion of MZ B cells is sufficient to prevent the development of detectable alloantibodies following RBC transfusion. However, because these results are built on model systems, future studies will be needed to further define the potential clinical utility of these findings.

Because TFH and FO B cells have previously been shown to be key players involved in the development of RBC alloantibody formation, the results of this study suggest that, in addition to these players, other immune populations may be involved in RBC alloimmunization. The distinct immune pathways engaged by the KEL and HOD RBC antigens warrant the development of additional model systems to determine the extent to which these immune pathways may overlap with other RBC alloantigens or whether other alloantigens induce alloantibodies through entirely distinct immune pathways. Such systems may also provide more insight into the characteristics of a given antigen that dictate which immune pathways are engaged. In doing so, the results of this and perhaps future studies using additional model systems of RBC alloimmunization may be helpful when seeking to identify common initiating pathways that could serve as possible future targets when seeking to reduce or prevent alloantibody formation following therapeutic transfusion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Burroughs Wellcome Trust Career Award for Medical Scientists; National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund grant DP5OD019892 and NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grants R01HL135575 and P01HL132819 (S.S.); the National Hemophilia Foundation-Shire Clinical Fellowship; the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society/Novo Nordisk Mentored Research Award in Hemophilia and Rare Bleeding Disorders; and the NIH Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Research Development Child Health Research Career Development Award Program, K12HD072245 Atlanta Pediatric Scholars Program (P.E.Z.). This research project was also supported, in part, by the Emory University Integrated Cellular Imaging Microscopy Core.

Authorship

Contribution: P.E.Z., S.R.P., C.M.A., and S.R.S. conceived the project, which was facilitated by R.P.J., J.W.M., J.W.L.A., S.C., R.F., J.D.R., C.D.J., and J.E.H. who provided key reagents, experimental support and critical discussion; and P.E.Z. and S.R.S. wrote the manuscript, which was commented on and edited by the other authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sean R. Stowell, Joint Program in Transfusion Medicine, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 630E New Research Building, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: srstowell@bwh.harvard.edu.

Data sharing requests should be sent to Sean R. Stowell (srstowell@bwh.harvard.edu).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal