Key Points

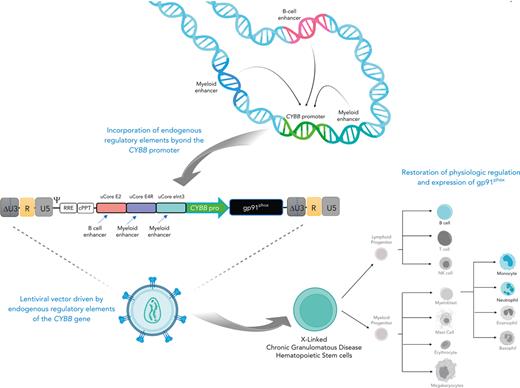

We used a bioinformatics-guided approach to design a lentiviral vector driven by endogenous enhancer and promoter elements of the CYBB gene.

Our novel vector restores physiologic regulation and expression of CYBB for the treatment of X-CGD.

Abstract

X-linked chronic granulomatous disease (X-CGD) is a primary immunodeficiency caused by mutations in the CYBB gene, resulting in the inability of phagocytic cells to eliminate infections. To design a lentiviral vector (LV) capable of recapitulating the endogenous regulation and expression of CYBB, a bioinformatics-guided approach was used to elucidate the cognate enhancer elements regulating the native CYBB gene. Using this approach, we analyzed a 600-kilobase topologically associated domain of the CYBB gene and identified endogenous enhancer elements to supplement the CYBB promoter to develop MyeloVec, a physiologically regulated LV for the treatment of X-CGD. When compared with an LV currently in clinical trials for X-CGD, MyeloVec showed improved expression, superior gene transfer to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), corrected an X-CGD mouse model leading to complete protection against Burkholderia cepacia infection, and restored healthy donor levels of antimicrobial oxidase activity in neutrophils derived from HSPCs from patients with X-CGD. Our findings validate the bioinformatics-guided design approach and have yielded a novel LV with clinical promise for the treatment of X-CGD.

Introduction

X-linked chronic granulomatous disease (X-CGD) is a primary immunodeficiency caused by mutations in the CYBB gene, which encodes for gp91phox, the catalytic subunit of the phagocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase complex. Mutations in CYBB result in the inability of phagocytic cells to produce antimicrobial oxidase needed for elimination of phagocytosed bacteria and fungi.1,2 Thus, patients suffer from recurrent life-threatening infections.3,4

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with gene therapy is a potentially curative treatment for X-CGD. However, prior lentiviral vector (LV) designs for X-CGD used noncognate enhancers in combination with either an exogenous myeloid promoter or the endogenous CYBB promoter and have been unable to restore wild-type (WT) levels of expression.5-7 The current LV for X-CGD in clinical trials is driven by a chimeric promoter comprising the c-Fes and cathepsin G promoter regions.8,9 Although patients in the ongoing trial have improved gp91phox expression, antimicrobial oxidase activity is restored to only ∼33% of healthy donor (HD) levels.8

The inability of prior LVs to restore physiologic expression and regulation is likely due to a lack of cognate enhancers supplementing the endogenous promoter within the LV cassette. Although gene editing strategies can potentially restore physiologic CYBB expression and regulation, these approaches either only target a specific mutation or have led to low efficiency of full-length complementary DNA insertion into long-term hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).10,11

To design a LV capable of restoring physiologic levels of gp91phox expression, we implemented a bioinformatics-based approach to identify the cognate enhancers regulating the CYBB gene. Our analysis revealed 15 putative endogenous elements contained within a 600-kilobase (kb) topologically associated domain (TAD). Each putative element was experimentally assessed for on-target lineage-specific enhancer activity, and key elements were used to design a physiologically regulated LV with optimized expression, titer, and gene transfer.

Here, we describe a bioinformatics-guided approach used to design a highly regulated LV and assess its ability to recapitulate the physiologic regulation and expression of the endogenous CYBB gene. In addition, we demonstrate the LV’s capacity to fully correct the X-CGD phenotype in both a X-CGD murine model and in cells from patients with X-CGD, restoring WT levels of gp91phox expression and antimicrobial oxidase activity. More broadly, we demonstrate a revolutionary approach to LV design, which may pave the way for new gene therapy targets requiring highly regulated expression.

Materials and methods

LVs

All LVs were cloned into an empty CCL backbone.12 Fragments were synthesized as gBlocks (Integrated DNA Technologies) or amplified from genomic DNA by polymerase chain reaction with compatible ends to be cloned using NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Kit (New England Biolabs). The CCLchim plasmid9 was kindly provided by Bobby Gaspar. LVs were packaged with a VSV-G pseudotype using 293T cells and concentrated and titered on HT-29 cells, as previously described.13 A good manufacturing practice–equivalent grade vector of MyeloVec was generated by the Indiana University Vector Production Facility and used for the in vitro genotoxicity studies.

Bioinformatic analysis

Genomic regions containing putative regulatory elements of the CYBB gene were compiled using data from ENCODE, Ensembl, FANTOM, and VISTA.14-17 Functional boundaries of the putative enhancer elements were defined using lineage-specific DNase I accessibility, transcription factor binding, epigenetic histone modification, and sequence conservation data from ENCODE.14

Mice

All animals involved were handled in accordance with protocols approved by the University of California, Los Angeles Animal Research Committee under the Division of Laboratory Medicine. B6.129S6-Cybbtm1Din/J (X-CGD mice), C57BL/6J, B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ (Pepboy), NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG), and NOD.Cg-KitW-41J Tyr + Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/ThomJ (NBSGW) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory, and colonies were maintained at University of California, Los Angeles.

NSG xenografts

Transduced CD34+ cells were washed and incubated with OKT3 (Tonbo Biosciences, 1 μg/100 μL) for 30 minutes at 4°C to prevent contaminating T-cell–derived graft-versus-host disease. Immediately before transplant, 1- to 3-day-old NSG neonatal mice were irradiated at a dose of 150 rads with a cesium-137 source. Each mouse was injected intrahepatically with 1 × 105 to 5 × 105 cells.

Murine X-CGD ex vivo gene therapy

For the CD45.2 into CD45.1 transplants, homozygous female X-CGD (CD45.2) Lin− cells were injected retro-orbitally into lethally irradiated 12-week-old female (CD45.1) Pepboy mice.

For the X-CGD into X-CGD transplants, hemizygous male X-CGD Lin− cells were injected retro-orbitally into lethally irradiated 10- to 14-week-old female X-CGD mice. All recipient mice received 2 doses of 600 rad irradiation administered 3 hours apart, 24 hours before transplant. For both experiments, recipient mice were injected with 1 × 106 cells.

Burkholderia cepacia infection

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 × 105 colony-forming units (CFUs) of B cepacia resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (ATCC #25609) and weighed daily for 14 days after infection. Peripheral blood (PB) was obtained via retro-orbital blood drawn 24 hours after infection, and bacteremia was evaluated by serial plate dilutions on agar 3 plates. Mice were euthanized if they lost >20% of their original body weight and were found moribund.

Genotoxicity evaluation

Results

Elucidating the elements that regulate the native CYBB gene

We first characterized the physiologic expression pattern of the CYBB gene in the bone marrow (BM) and PB of human HDs (supplemental Figure 1). In BM, we detected high levels of gp91phox expression in mature neutrophils and bulk myeloid cells, moderate expression in B cells, and no expression in either T cells or HSPCs (supplemental Figure 1A). Using previously described cell-surface markers,20 we also observed that gp91phox expression progressively increased throughout neutrophil differentiation (supplemental Figure 1C). Similar patterns of expression were observed in PB (supplemental Figure 1B).

To mimic this endogenous expression pattern, we initially evaluated all intronic regions of CYBB and 5000 base pairs immediately upstream of the CYBB promoter for DNase I hypersensitive sites suggestive of enhancer activity. This revealed an enhancer element in intron 3, which increased expression over 2.5-fold above the CYBB promoter alone in neutrophils and monocytes (supplemental Figure 1F). Intron 1 of the CYBB gene was previously suggested to have enhancer activity;21 however, we observed no effect on expression (supplemental Figure 1F).

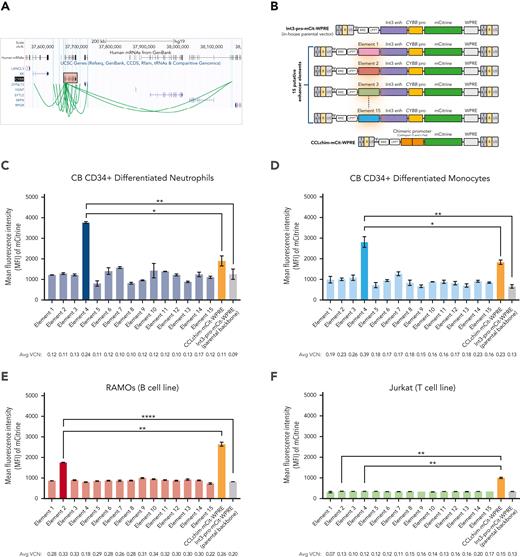

A further in-depth analysis of a 600-kb TAD surrounding the CYBB gene revealed 15 putative enhancer elements in addition to the previously identified intron 3 enhancer (Figure 1A). To assess the function of each putative enhancer element, we designed a series of LVs, each with a single enhancer element cloned upstream of both the intron 3 enhancer and the endogenous CYBB promoter to drive the expression of an mCitrine reporter (Figure 1B). For comparison to the LV currently in clinical trials for X-CGD,9 we included the chimeric promoter LV (CCLchim) in our studies.

Elucidating the endogenous elements that regulate the CYBB gene. (A) Visual representation of the University of California, Santa Cruz Genome Browser displaying putative enhancers regulating the native CYBB gene. The CYBB gene is highlighted in the red box. Green arches represent the putative genomic sites interacting with the CYBB promoter. (B) A series of LVs were designed, each containing a single putative enhancer element cloned upstream of the parental construct. The CCLchim vector is used as a comparator of expression and regulation. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the mCitrine-positive population is shown for the human cord blood CD34+ differentiated neutrophils (C) and monocytes (D) as well as the RAMOs (E) and Jurkat cell lines (F). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t test. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Int3 enh, CYBB intron 3 enhancer; mCit, mCitrine; ns, nonsignificant; pro, CYBB promoter; tRNA, transfer RNA; WPRE, Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element.

Elucidating the endogenous elements that regulate the CYBB gene. (A) Visual representation of the University of California, Santa Cruz Genome Browser displaying putative enhancers regulating the native CYBB gene. The CYBB gene is highlighted in the red box. Green arches represent the putative genomic sites interacting with the CYBB promoter. (B) A series of LVs were designed, each containing a single putative enhancer element cloned upstream of the parental construct. The CCLchim vector is used as a comparator of expression and regulation. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the mCitrine-positive population is shown for the human cord blood CD34+ differentiated neutrophils (C) and monocytes (D) as well as the RAMOs (E) and Jurkat cell lines (F). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t test. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Int3 enh, CYBB intron 3 enhancer; mCit, mCitrine; ns, nonsignificant; pro, CYBB promoter; tRNA, transfer RNA; WPRE, Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element.

To identify enhancers responsible for driving expression in each of the on-target cell lineages, we screened the LVs in human umbilical cord blood (CB) CD34+ differentiated neutrophils and monocytes, and in the RAMOS B-cell line. We also screened the LVs in the Jurkat T-cell line to detect any off-target expression. All vectors were transduced to achieve equivalent vector copy numbers (VCNs) ranging from ∼0.10 to 0.20 to increase the probability of each transduced cell containing a single integrant, based on the Poisson distribution,22,23 for equal comparison of expression per integrated copy while factoring out any benefits due to gene transfer (supplemental Figure 2). The addition of element 4 increased expression threefold to fourfold higher than the parental vector (Int3-pro-mCit-WPRE) and 1.5-fold to twofold higher than CCLchim in CD34+ differentiated neutrophils and monocytes (Figure 1C-D). Element 4 displayed no enhancer activity in RAMOS B cells, whereas element 2 increased expression over twofold higher than the parental vector (Figure 1E). Both elements 4 and 2 displayed no activity in Jurkat T cells, suggesting myeloid and B-cell lineage–specific activity, respectively (Figure 1F). By introducing a series of systematic deletions in these key elements to decrease proviral length, and combining these elements together, we generated our lead candidate, LV MyeloVec (Ultra-Core variant of 2-4R-Int3-pro-mCit-WPRE), with improved expression, titer, and gene transfer (supplemental Materials and Methods; supplemental Figures 3, 4A, and 5, available on the Blood website).

MyeloVec recapitulates the endogenous lineage-specific expression pattern of the native CYBB gene

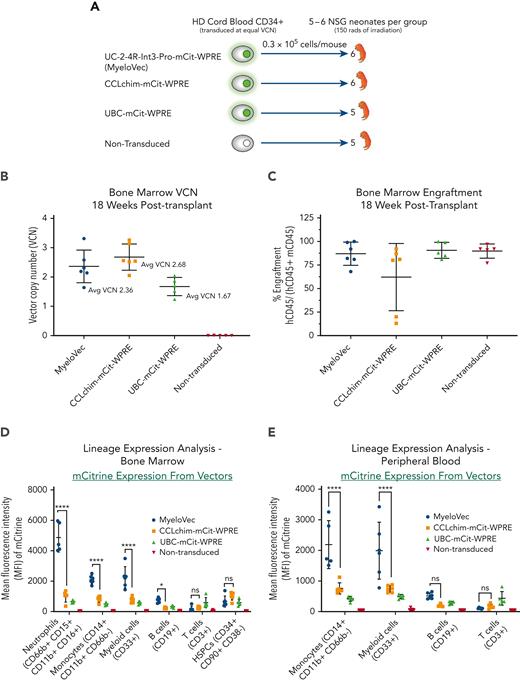

To investigate the lineage-specific expression pattern of MyeloVec in vivo, we transduced and transplanted human HD CB CD34+ HSPCs into sublethally irradiated NSG neonatal mice (Figure 2A). Experimental arms included MyeloVec, CCLchim, and ubiquitin C (UBC) vectors, all expressing mCitrine to display the expression pattern of each construct. The UBC promoter-driven construct is constitutively expressed in all lineages and was used as a positive control.24 We transduced cells in each experimental arm with the aim of achieving equivalent VCNs for an equal comparison of expression per copy (supplemental Table 1). At 18 weeks after transplantation, the average VCN in the BM of the mice was 2.36, 2.68, and 1.67 in the MyeloVec, CCLchim, and UBC treatment groups, respectively (Figure 2B). A majority of the mice had engraftment in the BM, ranging from 68% to 100% (Figure 3C). Two of the mice in the CCLchim treatment group had lower engraftment levels of 13% and 20%.

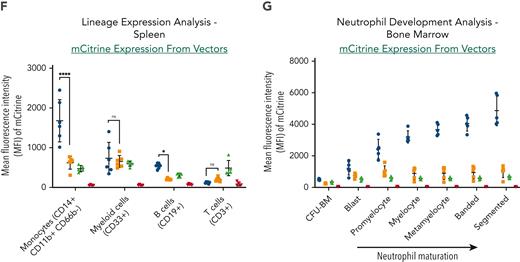

In vivo lineage-specific expression of MyeloVec. (A) Human HD CB CD34+ HSPCs were transduced and transplanted into sublethally irradiated NSG neonatal mice. Mice were harvested 18 weeks after transplant and stable BM VCN (B) and BM engraftment (C) were measured. Expression of each vector was evaluated across the different human hematopoietic lineages in the BM (D), PB (E), and spleen (F). (G) Kinetics of expression throughout neutrophil differentiation in the BM of engrafted mice. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using a 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by multiple paired comparisons for normally distributed data (Tukey test). All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Avg, average.

In vivo lineage-specific expression of MyeloVec. (A) Human HD CB CD34+ HSPCs were transduced and transplanted into sublethally irradiated NSG neonatal mice. Mice were harvested 18 weeks after transplant and stable BM VCN (B) and BM engraftment (C) were measured. Expression of each vector was evaluated across the different human hematopoietic lineages in the BM (D), PB (E), and spleen (F). (G) Kinetics of expression throughout neutrophil differentiation in the BM of engrafted mice. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using a 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by multiple paired comparisons for normally distributed data (Tukey test). All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Avg, average.

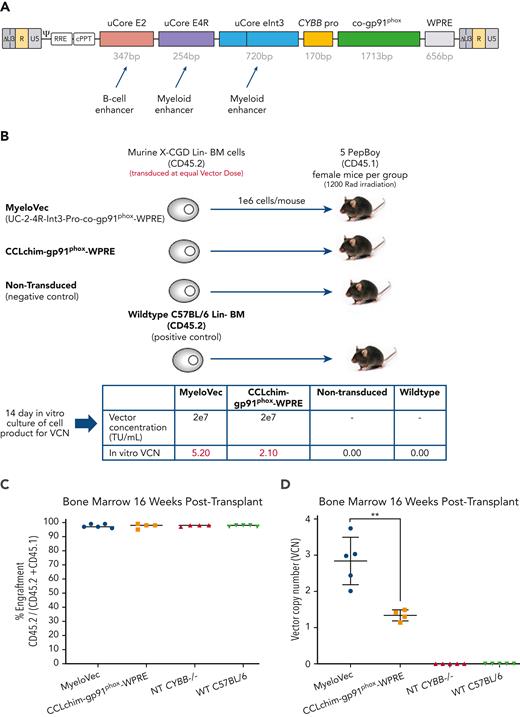

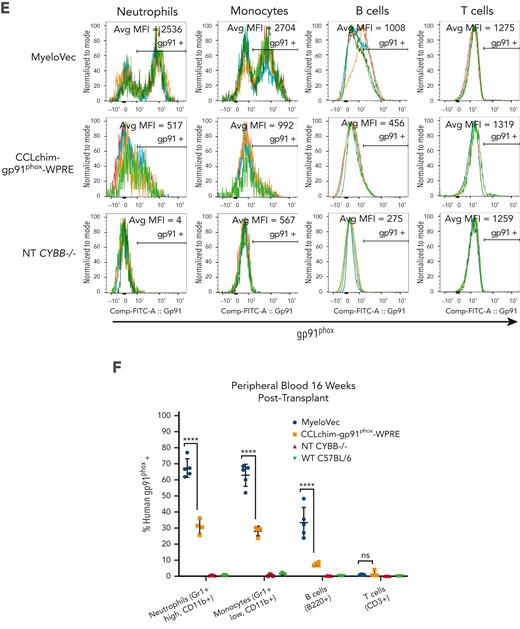

MyeloVec corrects the X-CGD mouse model in vivo. (A) Proviral map of MyeloVec. (B) Murine CD45.2 X-CGD Lin− HSPCs were transduced at an equal vector dose of 2e7 TU/mL and transplanted into congenic CD45.1 (Pepboy) mice. WT C57BL/6 HSPCs and nontransduced X-CGD HSPCs were also transplanted as positive and negative controls, respectively. VCN of the cell product are shown in the bottom panel. Mice were harvested 16 weeks after transplant and engraftment (C) and stable VCN (D) in the BM were measured. Restoration of gp91phox (E-F) and oxidase activity (G-H) was evaluated across the different lineages in the PB of the mice at time of harvest. Each mouse is represented as a different colored line in the histograms in panels E and G. MFI of gp91phox and rhodamine 123 of all cells within each lineage are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance for panel D was analyzed using an unpaired t test, whereas panels F and H used a 2-way ANOVA followed by multiple paired comparisons for normally distributed data (Tukey test). All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. bp, base pair; NT, nontransduced.

MyeloVec corrects the X-CGD mouse model in vivo. (A) Proviral map of MyeloVec. (B) Murine CD45.2 X-CGD Lin− HSPCs were transduced at an equal vector dose of 2e7 TU/mL and transplanted into congenic CD45.1 (Pepboy) mice. WT C57BL/6 HSPCs and nontransduced X-CGD HSPCs were also transplanted as positive and negative controls, respectively. VCN of the cell product are shown in the bottom panel. Mice were harvested 16 weeks after transplant and engraftment (C) and stable VCN (D) in the BM were measured. Restoration of gp91phox (E-F) and oxidase activity (G-H) was evaluated across the different lineages in the PB of the mice at time of harvest. Each mouse is represented as a different colored line in the histograms in panels E and G. MFI of gp91phox and rhodamine 123 of all cells within each lineage are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance for panel D was analyzed using an unpaired t test, whereas panels F and H used a 2-way ANOVA followed by multiple paired comparisons for normally distributed data (Tukey test). All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. bp, base pair; NT, nontransduced.

In the BM of the mice, MyeloVec displayed strict lineage-specific expression in vivo, with high mCitrine expression in neutrophils, monocytes, and bulk myeloid cells; modest expression in B cells; and minimal expression in T cells and HSPCs (Figure 2D). This corresponded to a 4.8-fold, 2.6-fold, and 2.9-fold higher expression compared with CCLchim in neutrophils, monocytes, and myeloid cells, respectively. A similar pattern of lineage-specific expression was observed in the PB and spleen (Figure 2E-F). As previously observed,25,26 we detected extremely low or no circulating neutrophils in the PB of transplanted NSG mice.

To assess the expression kinetics of MyeloVec throughout neutrophil differentiation, we measured mCitrine levels at each cellular stage of development in the BM. Expression from MyeloVec progressively increased as neutrophil progenitors matured, recapitulating the expression pattern seen with the endogenous CYBB gene throughout neutrophil maturation (Figure 2G; supplemental Figure 1C).

Correction of the murine X-CGD model

To assess MyeloVec’s ability to functionally correct the X-CGD phenotype, we replaced the mCitrine open reading frame with a JCat codon optimized27 version of CYBB, further increasing expression by 2.2-fold over the native CYBB complementary DNA sequence (supplemental Figure 4B; Figure 3A). Murine X-CGD HSPCs isolated from B6.129S6-Cybbtm1Din/J mice were then transduced with MyeloVec or CCLchim to achieve an equivalent VCN based on a previous dose response (supplemental Figure 6A) and differentiated into mature neutrophils in vitro (supplemental Figure 7). MyeloVec was used at a vector dose of 2.5e6 transduction units (TU)/mL (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 2.5), and CCLchim was used a vector dose of 2e7 TU/mL (MOI, 20) to achieve equivalent VCNs of 1.96 and 1.97, respectively, for an equal comparison of expression per copy while factoring out any benefits from increased gene transfer. At equivalent VCNs, MyeloVec restored gp91phox levels 1.67-fold higher than CCLchim (supplemental Figure 7A,C). Direct comparisons to WT gp91phox levels in the murine cells were not feasible as the antihuman gp91phox (7D5 clone) antibody only detected vector-derived human gp91phox expression but not endogenous murine gp91phox. However, we measured functional oxidase activity, and MyeloVec-transduced cells restored antimicrobial oxidase to WT levels in the murine X-CGD HPSC-derived neutrophils (supplemental Figure 7B,D).

To demonstrate in vivo correction of the X-CGD phenotype while taking into account both expression and gene transfer of the LV constructs, we transduced murine X-CGD HSPCs (CD45.2) with MyeloVec or CCLchim at an equal vector dose of 2e7 TU/mL (MOI, 20) and transplanted the cells into lethally ablated (CD45.1) Pepboy mice (Figure 3B). At 16 weeks after transplant, stable BM engraftment ranged from 95% to 99% across all treatment groups (Figure 3C). MyeloVec displayed superior gene transfer with average stable BM VCNs of 2.84 and 1.34 in the MyeloVec- and CCLchim-transplanted mice, respectively (Figure 3D). We observed lineage-specific expression of MyeloVec in the PB with high-level restoration of gp91phox in the mature neutrophil and monocyte populations (Figure 3E). Mice transplanted with MyeloVec-transduced cells produced an average of 67% gp91phox-positive neutrophils compared with 30% gp91phox-positive neutrophils seen in the CCLchim treatment group (Figure 3F). All nontreated mice showed a complete absence of gp91phox-positive neutrophils. Oxidase activity was fully restored to WT levels in PB neutrophils of MyeloVec-treated mice (Figure 3G). We also observed an increase in oxidase-positive neutrophils, with 72% and 55% oxidase-positive neutrophils detected in the PB of MyeloVec- and CCLchim-treated mice, respectively (Figure 3H). Analysis of the BM of MyeloVec-transplanted mice displayed lineage-specific restoration of gp91phox, mimicking the pattern seen with the WT-transplanted cells (supplemental Figure 8).

Maintenance of gp91phox expression, oxidase activity, and VCN in secondary transplants

In a separate experiment, we transduced murine X-CGD HPSCs with MyeloVec or CCLchim to achieve equivalent VCNs for transplantation into Pepboy mice. After 16 weeks, whole BM from the primary transplants was harvested and transplanted into secondary Pepboy mice for an additional 16 weeks to evaluate long-term maintenance of gp91phox expression, oxidase activity, and VCN. We detected similar levels of gp91phox-positive and dihydrorhodamine-positive (DHR+) cells in all lineages between the primary and secondary transplanted mice (supplemental Figure 9). The average BM VCN was also maintained between the primary and secondary transplants. Lineage distribution of engrafted MyeloVec cells was similar to that of HD controls in both the primary and secondary transplants.

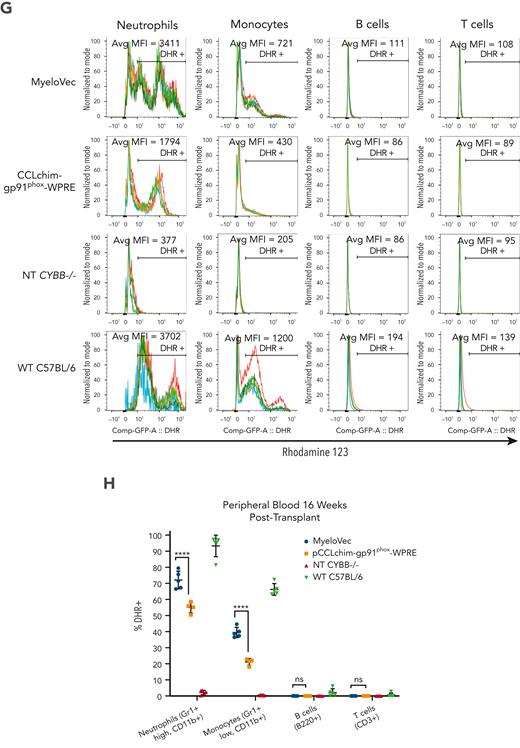

Infectious challenge

To evaluate the restoration of protective immune responses to bacterial pathogens after gene therapy, we transduced murine X-CGD HSPCs with either MyeloVec or CCLchim at an equal vector dose of 1 × 107 TU/mL and transplanted the cells into lethally ablated X-CGD mice (Figure 4A). At 8 weeks after transplant, the average VCN in the PB of MyeloVec- and CCLchim-treated mice were 2.83 and 1.32, respectively, which corresponded with 76% and 63% DHR+ PB neutrophils (Figure 4B-C). At 11 weeks after transplant, mice were infected with 1 × 105 CFUs of B cepacia injected intraperitoneally. PB was drawn to quantify bacteremia 24 hours after transplant. MyeloVec-treated mice, mice receiving WT HSPCs, and nontransplanted WT C57BL/6 mice all displayed very low or absent levels of bacteremia, whereas the CCLchim-treated mice and mice transplanted with nontransduced X-CGD HSPCs had an average of 4.05 CFU per μL and 25.95 CFU per μL of blood, respectively (Figure 4D). Body weights of the mice were monitored preinfection and daily for 14 days postinfection (Table 1). All MyeloVec-treated mice survived the infectious challenge and regained weight, whereas 80% of the CCLchim-treated mice developed a fatal infection (Figure 4E; Table 1). X-CGD mice transplanted with nontransduced X-CGD Lin− cells all developed fatal infections by 3 days after infection, whereas X-CGD mice transplanted with WT HSPCs and nontransplanted WT C57BL/6 mice all survived and regained weight throughout the study.

MyeloVec gene therapy protects X-CGD mice from B cepacia infection. (A) Murine X-CGD Lin− HSPCs were transduced with MyeloVec or pCCLchim at an equal vector dose of 2e7 TU/mL and transplanted into X-CGD mice. WT C57BL/6 HSPCs and nontransduced X-CGD HSPCs were also transplanted as positive and negative controls, respectively. Nontransplanted WT C57BL/6 mice were also included in the study as a positive control. Stable VCN (B) and percentage of DHR+ neutrophils (C) in the PB of the transplanted mice were measured 8 weeks after transplant. (D) Bacteremia was quantified 24 hours after infection as CFU per μL in the PB. (E) Proportion of surviving mice 14 days post experimental infection with 1 × 105B cepacia is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance for panels B-D was analyzed using an unpaired t test. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. i.p., intraperitoneally.

MyeloVec gene therapy protects X-CGD mice from B cepacia infection. (A) Murine X-CGD Lin− HSPCs were transduced with MyeloVec or pCCLchim at an equal vector dose of 2e7 TU/mL and transplanted into X-CGD mice. WT C57BL/6 HSPCs and nontransduced X-CGD HSPCs were also transplanted as positive and negative controls, respectively. Nontransplanted WT C57BL/6 mice were also included in the study as a positive control. Stable VCN (B) and percentage of DHR+ neutrophils (C) in the PB of the transplanted mice were measured 8 weeks after transplant. (D) Bacteremia was quantified 24 hours after infection as CFU per μL in the PB. (E) Proportion of surviving mice 14 days post experimental infection with 1 × 105B cepacia is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance for panels B-D was analyzed using an unpaired t test. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. i.p., intraperitoneally.

Body weight of mice throughout 14-d infectious challenge with 1 × 105B cepacia

| Days post infection . | 0 . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MyeloVec, % of original body weight | 100 | 94 | 90 | 90 | 91 | 92 | 95 | 96 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 91 | 91 | 94 |

| 100 | 97 | 94 | 93 | 92 | 98 | 101 | 103 | 104 | 101 | 102 | 101 | 102 | 104 | 103 | |

| 100 | 92 | 89 | 88 | 88 | 91 | 95 | 93 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 97 | 98 | 98 | |

| 100 | 94 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 91 | 91 | 87 | 91 | 94 | 96 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 98 | |

| 100 | 95 | 86 | 91 | 93 | 95 | 93 | 91 | 93 | 90 | 98 | 100 | 102 | 105 | 105 | |

| pCCLchim-gp91phox-WPRE, % of original body weight | 100 | 91 | 85 | 78 | dead | ||||||||||

| 100 | 94 | 88 | 82 | dead | |||||||||||

| 100 | 98 | 95 | 99 | 96 | 98 | 102 | 103 | 102 | 100 | 102 | 102 | 103 | 106 | 106 | |

| 100 | 94 | 88 | 87 | 82 | 76 | dead | |||||||||

| 100 | 91 | 83 | 80 | dead | |||||||||||

| Nontransduced CYBB−/− Lin− cells, % of original body weight | 100 | 88 | 84 | dead | |||||||||||

| 100 | 88 | dead | |||||||||||||

| 100 | 90 | 83 | dead | ||||||||||||

| 100 | 87 | 80 | dead | ||||||||||||

| 100 | 90 | 83 | dead | ||||||||||||

| WT C57BL/6 Lin− cells, % of original body weight | 100 | 94 | 94 | 91 | 94 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98 | 98 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| 100 | 96 | 91 | 89 | 87 | 90 | 92 | 95 | 96 | 95 | 94 | 97 | 97 | 100 | 101 | |

| 100 | 94 | 93 | 98 | 97 | 102 | 104 | 102 | 103 | 102 | 99 | 97 | 96 | 98 | 98 | |

| 100 | 94 | 91 | 97 | 95 | 97 | 100 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 102 | 101 | |

| 100 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 103 | 103 | 103 | 102 | 108 | 97 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 100 | |

| WT C57BL/6 (nontransplanted mice), % of original body weight | 100 | 100 | 98 | 103 | 100 | 103 | 101 | 99 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 99 |

| 100 | 96 | 96 | 100 | 97 | 96 | 95 | 95 | 99 | 98 | 95 | 94 | 97 | 98 | 97 | |

| 100 | 99 | 97 | 101 | 100 | 103 | 101 | 100 | 103 | 100 | 96 | 95 | 97 | 98 | 98 |

| Days post infection . | 0 . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . | 14 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MyeloVec, % of original body weight | 100 | 94 | 90 | 90 | 91 | 92 | 95 | 96 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 91 | 91 | 94 |

| 100 | 97 | 94 | 93 | 92 | 98 | 101 | 103 | 104 | 101 | 102 | 101 | 102 | 104 | 103 | |

| 100 | 92 | 89 | 88 | 88 | 91 | 95 | 93 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 97 | 98 | 98 | |

| 100 | 94 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 91 | 91 | 87 | 91 | 94 | 96 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 98 | |

| 100 | 95 | 86 | 91 | 93 | 95 | 93 | 91 | 93 | 90 | 98 | 100 | 102 | 105 | 105 | |

| pCCLchim-gp91phox-WPRE, % of original body weight | 100 | 91 | 85 | 78 | dead | ||||||||||

| 100 | 94 | 88 | 82 | dead | |||||||||||

| 100 | 98 | 95 | 99 | 96 | 98 | 102 | 103 | 102 | 100 | 102 | 102 | 103 | 106 | 106 | |

| 100 | 94 | 88 | 87 | 82 | 76 | dead | |||||||||

| 100 | 91 | 83 | 80 | dead | |||||||||||

| Nontransduced CYBB−/− Lin− cells, % of original body weight | 100 | 88 | 84 | dead | |||||||||||

| 100 | 88 | dead | |||||||||||||

| 100 | 90 | 83 | dead | ||||||||||||

| 100 | 87 | 80 | dead | ||||||||||||

| 100 | 90 | 83 | dead | ||||||||||||

| WT C57BL/6 Lin− cells, % of original body weight | 100 | 94 | 94 | 91 | 94 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98 | 98 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| 100 | 96 | 91 | 89 | 87 | 90 | 92 | 95 | 96 | 95 | 94 | 97 | 97 | 100 | 101 | |

| 100 | 94 | 93 | 98 | 97 | 102 | 104 | 102 | 103 | 102 | 99 | 97 | 96 | 98 | 98 | |

| 100 | 94 | 91 | 97 | 95 | 97 | 100 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 102 | 101 | |

| 100 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 103 | 103 | 103 | 102 | 108 | 97 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 100 | |

| WT C57BL/6 (nontransplanted mice), % of original body weight | 100 | 100 | 98 | 103 | 100 | 103 | 101 | 99 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 99 |

| 100 | 96 | 96 | 100 | 97 | 96 | 95 | 95 | 99 | 98 | 95 | 94 | 97 | 98 | 97 | |

| 100 | 99 | 97 | 101 | 100 | 103 | 101 | 100 | 103 | 100 | 96 | 95 | 97 | 98 | 98 |

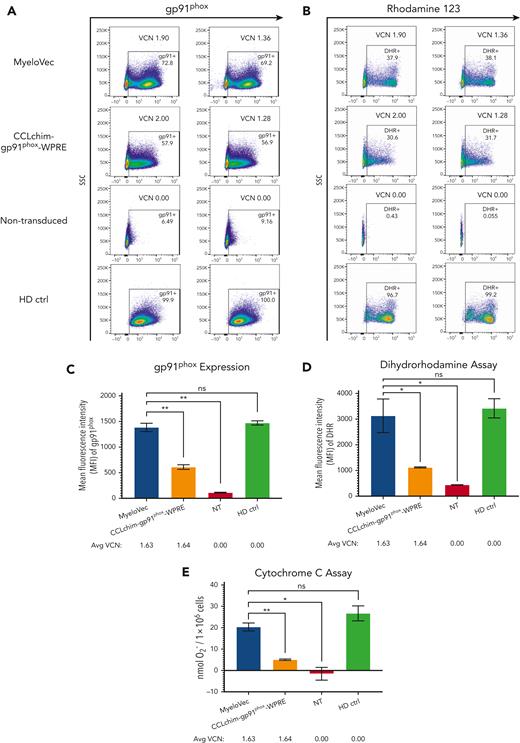

Correction of HSPCs from patients with X-CGD

To demonstrate the ability of MyeloVec to correct HSPCs from patients with X-CGD, CD34-selected HPSCs were transduced with MyeloVec or CCLchim to achieve equivalent VCNs and differentiated in vitro to produce mature neutrophils (Figure 5). At an equivalent VCN of 1.90 and 2.00, 72.8% and 57.9% gp91phox-positive neutrophils were produced in the MyeloVec- and CCLchim-transduced cells, respectively (Figure 5A). Within the bulk neutrophil population, MyeloVec-transduced cells restored HD levels of gp91phox at an average VCN of 1.63, whereas CCLchim was only able to restore gp91phox levels to 40% of HD levels at an equivalent VCN (Figure 5C). Oxidase-positive neutrophils displayed HD levels of cellular oxidase activity when transduced with MyeloVec, whereas CCLchim-transduced cells showed 33% of HD levels (Figure 5B,D). Furthermore, MyeloVec-transduced cells generated HD levels of superoxide, whereas the CCLchim-transduced cells only produced 19% of HD levels of O2− at an equivalent VCN (Figure 5E).

MyeloVec fully restores HD levels of gp91phox and cellular oxidase in human X-CGD HSPC-derived neutrophils. HSPCs from patients with X-CGD were transduced with MyeloVec or CCLchim and differentiated into mature neutrophils in vitro. (A) Restoration of gp91phox was measured at day 18 of differentiation. (B) Oxidase activity of the mature neutrophils was measured by DHR flow cytometry. (C) MFI of the entire neutrophil population is shown. (D) MFI of the DHR+ neutrophils is shown. (E) Production of reactive oxygen species was measured by the cytochrome C assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t test. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ctrl, control.

MyeloVec fully restores HD levels of gp91phox and cellular oxidase in human X-CGD HSPC-derived neutrophils. HSPCs from patients with X-CGD were transduced with MyeloVec or CCLchim and differentiated into mature neutrophils in vitro. (A) Restoration of gp91phox was measured at day 18 of differentiation. (B) Oxidase activity of the mature neutrophils was measured by DHR flow cytometry. (C) MFI of the entire neutrophil population is shown. (D) MFI of the DHR+ neutrophils is shown. (E) Production of reactive oxygen species was measured by the cytochrome C assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t test. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ctrl, control.

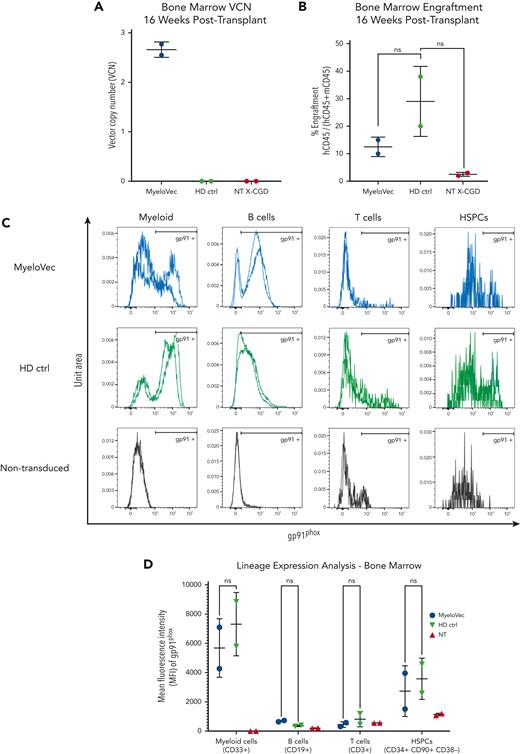

To evaluate the correction of HSPCs from patients with X-CGD in vivo, MyeloVec-transduced HSPCs were transplanted into sublethally irradiated NSG neonatal mice. Control mice received nontransduced X-CGD or HD HSPCs. At 16 weeks after transplant, the average stable VCN of MyeloVec-treated mice was 2.66, and engraftment ranged from 10% to 12.5% in the MyeloVec-treated mice compared with 2.5% to 3% in mice transplanted with nontransduced X-CGD HSPCs (Figure 6A-B). Mice transplanted with MyeloVec-transduced X-CGD HSPCs restored gp91phox expression to HD levels in the myeloid, B-cell, T-cell, and HSPC lineages (Figure 6C-D). Lineage distribution of the engrafted MyeloVec-transduced patient cells was similar to HD controls (supplemental Figure 10).

MyeloVec restores gp91phox expression in human X-CGD BM cells engrafted into NSG mice. Human X-CGD CD34+ HSPCs were engrafted into NSG mice. Mice were harvested 16 weeks after transplant and stable BM VCN (A) and engraftment of human cells (B) were analyzed. (C) Restoration of gp91phox was measured across the different hematopoietic lineages in the BM. Data from each mouse are overlaid in the histograms. (D) The MFI of gp91phox-positive cells is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA followed by multiple paired comparisons for normally distributed data (Tukey test). All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

MyeloVec restores gp91phox expression in human X-CGD BM cells engrafted into NSG mice. Human X-CGD CD34+ HSPCs were engrafted into NSG mice. Mice were harvested 16 weeks after transplant and stable BM VCN (A) and engraftment of human cells (B) were analyzed. (C) Restoration of gp91phox was measured across the different hematopoietic lineages in the BM. Data from each mouse are overlaid in the histograms. (D) The MFI of gp91phox-positive cells is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA followed by multiple paired comparisons for normally distributed data (Tukey test). All statistical tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was deemed significant; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Long-term persistence of MyeloVec-transduced HSPCs

To evaluate the long-term maintenance of MyeloVec-transduced HSPCs, NBSGW mice were transplanted with MyeloVec or mock-transduced HD HSPCs. At 16 weeks after transplant, mice were harvested, and the whole BM was transplanted into secondary NBSGW mice for an additional 8 weeks. Similar VCNs were observed in the whole BM of the primary and secondary mice and also in the sorted CD34+ CD38− primitive HSPCs in the BM of the secondary mice (supplemental Figure 11).

Safety profile of MyeloVec

To evaluate the safety profile of MyeloVec, we performed an IVIM assay using good manufacturing practice–equivalent MyeloVec LV. Both MyeloVec- and CCLchim-transduced cells did not elicit the growth of insertional mutants (Figure 7A) and showed normal proliferation rates and viability compared with controls (supplemental Figure 12A). We also performed SAGA to evaluate whether MyeloVec dysregulated gene expression. A positive normalized enrichment score (NES) indicates an upregulation of a core set of oncogenic genes. All MyeloVec-transduced samples displayed negative NES scores, whereas 1 out of 6 and 8 out of 8 CCLchim and RSF91 samples had positive NES scores, respectively (Figure 7B; supplemental Figure 12B). In addition, we performed a CFU assay using MyeloVec-transduced HD CD34+ cells. Clonal output and lineage distribution was similar to that of nontransduced controls (supplemental Figure 13).

Safety profile of MyeloVec. (A) IVIM assay displaying the replating frequency (RF) of MyeloVec and CCLchim-gp91phox-WPRE and control samples (Mock and RSF91). Data are compared with a meta-analysis (MA) for control samples (MA-Mock, MA-RSF91, MA-LV-SF). Above the graph, the incidence of positive (RF >3.17 × 10−4) and negative plates (RF <3.17 × 10−4) according to the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay are shown. (B) SAGA assay displaying gene expression analysis. A positive NES indicates an upregulation of oncogenic core set genes. Data are compared with a MA of a positive control (MARSF91) or SIN LV with an internal EFS promoter (MA-LV.EFS). Plates with no wells above the MTT threshold. Bars indicate means. Difference in the incidence of positive and negative IVIM assays relative to Mock-MA or RSF91-MA were analyzed by Fisher exact test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Statistical comparison with MA-RSF-91 in SAGA was analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn correction; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. RSF91, mutagenic gammaretroviral vector with enhancer/promoter of spleen focus–forming virus in both LTRs; LV-SF, self-inactivating LV under control of the spleen focus–forming virus internal promoter; EFS, self-inactivating LV under control of the shorten promoter of the EEF1A1 gene; LOD, limitation of detection.

Safety profile of MyeloVec. (A) IVIM assay displaying the replating frequency (RF) of MyeloVec and CCLchim-gp91phox-WPRE and control samples (Mock and RSF91). Data are compared with a meta-analysis (MA) for control samples (MA-Mock, MA-RSF91, MA-LV-SF). Above the graph, the incidence of positive (RF >3.17 × 10−4) and negative plates (RF <3.17 × 10−4) according to the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay are shown. (B) SAGA assay displaying gene expression analysis. A positive NES indicates an upregulation of oncogenic core set genes. Data are compared with a MA of a positive control (MARSF91) or SIN LV with an internal EFS promoter (MA-LV.EFS). Plates with no wells above the MTT threshold. Bars indicate means. Difference in the incidence of positive and negative IVIM assays relative to Mock-MA or RSF91-MA were analyzed by Fisher exact test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Statistical comparison with MA-RSF-91 in SAGA was analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn correction; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. RSF91, mutagenic gammaretroviral vector with enhancer/promoter of spleen focus–forming virus in both LTRs; LV-SF, self-inactivating LV under control of the spleen focus–forming virus internal promoter; EFS, self-inactivating LV under control of the shorten promoter of the EEF1A1 gene; LOD, limitation of detection.

Discussion

We have implemented a bioinformatics-guided approach to develop a highly regulated LV driven by endogenous regulatory elements of the CYBB gene. Our initial proximal analysis revealed an enhancer located within intron 3 of CYBB with lineage-specific activity in neutrophils, monocytes, and B cells. Further analysis of the entire TAD revealed 2 additional genomic elements vital for the physiological expression pattern of the CYBB gene. Element 4, located 25 kb upstream of the CYBB promoter, presented as a myeloid-specific enhancer lacking activity in lymphoid cell lineages. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing transcription factor–binding site data from ENCODE revealed various myeloid-associated transcription factor–binding sites such as PU.1, SP1, and GABP within element 4.

Element 2, located 38 kb downstream of the CYBB promoter, was found to be a B-cell–specific enhancer with no enhancer activity in either the myeloid or T-cell lineages. Many of the current LV designs for X-CGD primarily focus on myeloid expression while overlooking restoration of gp91phox in the B-cell compartment.5,6,9 However, as we and others have shown, gp91phox is expressed in B cells and is capable of producing low levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS).28 It has been hypothesized that this low level of ROS facilitates regulatory and signaling functions.28,29 Furthermore, loss of gp91phox expression and ROS production in the B-cell lineage has been shown to impair the memory B-cell compartment and proliferative capabilities.30 Accordingly, we rationalized the importance of recapitulating the expression of gp91phox in all physiologically expressed lineages.

As titer and gene transfer have been previously shown to be negatively correlated with proviral length,31,32 we introduced a series of systematic deletions to decrease the proviral length of our vector and increased titer and gene transfer by 3.3- and 10-fold, respectively. Improvements to titer and gene transfer are considerably beneficial for the clinical translation of our therapy, as they drastically reduce the cost of vector production and the amount of LV required to treat each patient.

Removing nearly 3 kb of proviral sequences also led to an unexpected increase in expression in the on-target cell lineages, whereas off-target expression remained undetectable. At present, the mechanism behind this increase in expression is not well understood considering our previous observation of a positive correlation between the size of enhancer elements and their enhancer activity.33 A plausible explanation may be that the removal of inert sequences brought the core enhancer fragment closer to the promoter, leading to increased expression. Alternatively, it is plausible that the removal of potential transcriptional repressor–binding sites led to an increase in enhancer activity. Loss of regulation is a concern with this unexpected amplification in expression, however, off-target activity remained negligible.

Reporter gene studies in transduced human CB CD34+ cells transplanted into NSG neonates demonstrated preferential expression of MyeloVec in the mature neutrophil and bulk myeloid lineages, with moderate expression in the B-cell lineage and minimal expression in either the T-cell or HSPC populations. Furthermore, MyeloVec exhibited stage-specific expression that increased through neutrophil differentiation. As such, MyeloVec’s expression recapitulates the expression pattern seen with the endogenous CYBB gene.

Both gene transfer and expression are important metrics contributing to the therapeutic potential of an LV. An improvement in gene transfer increases the number of transduced cells and also leads to more integrated copies of the LV per transduced cell, thereby increasing overall cellular expression, whereas an improvement in expression directly leads to more therapeutic protein being produced per integrated copy. To emphasize the improved expression of MyeloVec per vector copy while factoring out any benefits from improved gene transfer, we lowered the LV dose of MyeloVec in the in vitro studies to compare MyeloVec to CCLchim at an equal VCN. However, in other studies, we evaluated the vectors at an equal vector dose, factoring in both expression and gene transfer to fully showcase the therapeutic potential of MyeloVec.

B cepacia is one of the main micro-organisms responsible for infections in patients with CGD and a leading cause of death, second only to Aspergillus.3,4 In an experimental infectious challenge with B cepacia, X-CGD mice transplanted with MyeloVec-transduced X-CGD HSPCs provided a complete survival benefit compared with X-CGD mice receiving CCLchim-transduced X-CGD HSPCs at an equal vector dose. The reasons for the survival of the MyeloVec-treated mice are likely twofold, owing to a greater number of gene-corrected oxidase-positive neutrophils and a greater level of antimicrobial oxidase per gene-corrected cell, due to the higher gene transfer and expression of MyeloVec, respectively. This observation agrees with Dinauer et al,34 who suggested that both the relative cellular level of antibacterial oxidase and the number of oxidase-positive neutrophils contribute to the level of protection against B cepacia, especially with a large number inoculum.

In neutrophils derived from transduced HSPCs from patients with X-CGD, MyeloVec fully restored gp91phox and cellular oxidase activity to HD levels at an average VCN of 1.63, whereas CCLchim was only able to restore cellular oxidase activity to 33% at an equal VCN. This difference in expression between MyeloVec and CCLchim is more pronounced in human than in murine neutrophils as MyeloVec is composed of human regulatory elements, which may have enhanced expression and regulation in human cells as it is optimized to be bound by human transcription factors.

It is notable to point out that gp91phox was detected in HSPCs in the BM of mice engrafted with HD HSPCs but was not detected in primary human HD BM samples. This may be due to the phenotypic differences of HSPCs residing in primary human BM compared with those in the BM of engrafted mice. Nevertheless, MyeloVec restored gp91phox to physiological levels in HSPCs from patients with X-CGD engrafted into NSG mice.

The incorporation of novel enhancer elements into a lentiviral gene therapy raises concerns about insertional mutagenesis due to transactivation of oncogenes. However, the restriction of enhancer activity toward the mature myeloid lineages rather than in early progenitors greatly reduces this risk.35 This is further supported by both IVIM and SAGA, demonstrating that MyeloVec has undetectable transformative capabilities.

In the context of gene therapy for X-CGD, regulated expression is an important factor to consider, as constitutive overexpression of gp91phox in HSPCs has been hypothesized to trigger aberrant ROS production, leading to decreased engraftment potential.36,37 Furthermore, uncontrolled expression of gp91phox may increase the risk of an immune response against the gene-modified cells. Similarly, achieving physiological levels of expression must also be considered, as subphysiological antimicrobial oxidase activity may not provide complete protection, as shown in our experimental infectious challenge and as previously suggested.34

Although MyeloVec is not the first LV to be fully regulated by endogenous elements of the target gene, our work demonstrates the implementation of a predictive bioinformatics-guided approach coupled with experimental validation which can be applied to other gene targets. The outcome of this study has not only yielded a novel LV for the treatment of X-CGD with potential to advance to the clinic, but it will also transform the design of future LVs for gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Harry Malech for kindly providing the CD34+ cells from patients with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease used in this study (Intramural National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease supported, institutional review board approved protocol 94-I-0073). Bobby Gaspar kindly provided the CCLchim9 plasmid and Adrian Thrasher provided the human PLB985 CYBB−/− cell line. Michael Rothe and Axel Schambach performed in vitro immortalization and surrogate assay for genotoxicity assessment. Felicia Codrea, Jessica Scholes, and Jeffrey Calimlim provided essential support through the Flow Cytometry Core of the Eli & Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine & Stem Cell Research (University of California, Los Angeles Broad Stem Cell Research Center). Blood products were provided by the University of California, Los Angeles/Center for AIDS Research Virology Core Lab (5P30 AI028697). The authors additionally thank Grace E. McAuley and Paul G. Ayoub for insightful comments in reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by unrestricted funds from the University of California, Los Angeles Broad Stem Cell Research Center.

Authorship

Contribution: R.L.W. conceived, designed, and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; S. Sackey, D.B., S. Senadheera, K.M., J.P.Q., N.C., and L.R., assisted in performing experiments; R.A.M. advised and performed experiments; H.M. provided patient samples; and R.P.H. and D.B.K. advised the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.L.W., K.M., J.P.Q., N.C., L.R., and R.P.H. are full-time employees of ImmunoVec Inc. H.M. and D.B.K. are consultants to ImmunoVec Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Donald B. Kohn, Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Molecular Genetics, University of California, Los Angeles, 3163 Terasaki Life Sciences Building, 610 Charles E. Young Dr East, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1489; e-mail: dkohn1@mednet.ucla.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Donald B. Kohn (dkohn1@mednet.ucla.edu).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Safety profile of MyeloVec. (A) IVIM assay displaying the replating frequency (RF) of MyeloVec and CCLchim-gp91phox-WPRE and control samples (Mock and RSF91). Data are compared with a meta-analysis (MA) for control samples (MA-Mock, MA-RSF91, MA-LV-SF). Above the graph, the incidence of positive (RF >3.17 × 10−4) and negative plates (RF <3.17 × 10−4) according to the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay are shown. (B) SAGA assay displaying gene expression analysis. A positive NES indicates an upregulation of oncogenic core set genes. Data are compared with a MA of a positive control (MARSF91) or SIN LV with an internal EFS promoter (MA-LV.EFS). Plates with no wells above the MTT threshold. Bars indicate means. Difference in the incidence of positive and negative IVIM assays relative to Mock-MA or RSF91-MA were analyzed by Fisher exact test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Statistical comparison with MA-RSF-91 in SAGA was analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn correction; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. RSF91, mutagenic gammaretroviral vector with enhancer/promoter of spleen focus–forming virus in both LTRs; LV-SF, self-inactivating LV under control of the spleen focus–forming virus internal promoter; EFS, self-inactivating LV under control of the shorten promoter of the EEF1A1 gene; LOD, limitation of detection.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/141/9/10.1182_blood.2022016074/2/m_blood_bld-2022-016074-gr7.jpeg?Expires=1770387838&Signature=le-kL-9NTJhhsYsHCkWobBmdHsnOjHp2s3bfMiKK9LZT~6nRBVZKYmC6QpEOk1EAZMGox47pwH7YZdeb94RDUd5hVUVgEf9uwJ15vD6KvIpvvcOPlLtT8H5tz5VU0CtYPxTfy2ZwfwSp8F8FHzxbiKqe95~NgUsF8vX6D05iJJW7Ac0mUcIX1cZyZVWLSLwWIVih9-R5YjJw7nOPB83pNoCfyYfqyVyphm4NXvPrZSNAGjSrMrleQP-T6OZd8bFcJDLaCyPYEFKKTdglECjRxV7CSoet45gfvyp7nNE2T7bhO2trgj3f-MIikKGpH9Jk43O8cGvuA~zDnTn0Pnu98A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal