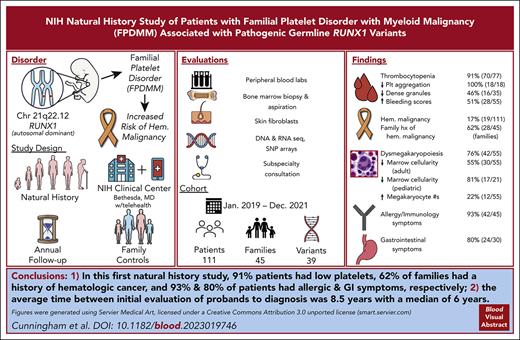

First report, to our knowledge, of clinical findings from a comprehensive longitudinal natural history study of patients with germ line RUNX1 variants.

A total of 91% patients had low platelets, 62% families had history of hematologic cancer; 93% and 80% patients had allergic and GI symptoms, respectively.

Visual Abstract

Deleterious germ line RUNX1 variants cause the autosomal dominant familial platelet disorder with associated myeloid malignancy (FPDMM), characterized by thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction, and a predisposition to hematologic malignancies (HMs). We launched a FPDMM natural history study and, from January 2019 to December 2021, enrolled 214 participants, including 111 patients with 39 different RUNX1 variants from 45 unrelated families. Seventy of 77 patients had thrombocytopenia, 18 of 18 had abnormal platelet aggregometry, 16 of 35 had decreased platelet dense granules, and 28 of 55 had abnormal bleeding scores. Nonmalignant bone marrows showed increased numbers of megakaryocytes in 12 of 55 patients, dysmegakaryopoiesis in 42 of 55, and reduced cellularity for age in 30 of 55 adult and 17 of 21 pediatric cases. Of 111 patients, 19 were diagnosed with HMs, including myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and smoldering myeloma. Of those 19, 18 were relapsed or refractory to upfront therapy and referred for stem cell transplantation. In addition, 28 of 45 families had at least 1 member with HM. Moreover, 42 of 45 patients had allergic symptoms, and 24 of 30 had gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Our results highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary approach, early malignancy detection, and wider awareness of inherited disorders. This actively accruing, longitudinal study will genotype and phenotype more patients with FPDMM, which may lead to a better understanding of the disease pathogenesis and clinical course, which may then inform preventive and therapeutic interventions. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT03854318.

Medscape Continuing Medical Education online

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology. Medscape, LLC is jointly accredited with commendation by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Successful completion of this CME activity, which includes participation in the evaluation component, enables the participant to earn up to 1.0 MOC points in the American Board of Internal Medicine's (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. Participants will earn MOC points equivalent to the amount of CME credits claimed for the activity. It is the CME activity provider's responsibility to submit participant completion information to ACCME for the purpose of granting ABIM MOC credit.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at https://www.medscape.org/journal/blood; and (4) view/print certificate. For CME questions, see page 2222.

Disclosures

CME questions author Laurie Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC, declares no competing financial interests.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will:

Describe genetic, hematological and bone marrow findings of patients with familial platelet disorder with associated myeloid malignancy (FPDMM) enrolled in an ongoing prospective, longitudinal NIH study from early 2019 to December 2021

Determine other clinical findings of patients with FPDMM enrolled in an ongoing prospective, longitudinal NIH study from early 2019 to December 2021

Identify clinical implications of preliminary findings of patients with FPDMM enrolled in an ongoing prospective, longitudinal NIH study from early 2019 to December 2021

Release date: December 21, 2023; Expiration date: December 21, 2024

Introduction

The RUNX1 gene encodes a master regulator of definitive hematopoiesis.1RUNX1 somatic variants and translocations are among the most frequently identified defects in hematologic malignancies (HMs).2-7 In contrast, germ line RUNX1 variants are thought to be relatively rare, having been described in ∼200 families worldwide.8 In 1999, Song et al reported that germ line RUNX1 variants cause an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by lifelong mild/moderate thrombocytopenia, qualitative platelet dysfunction, and predisposition to HMs,9,10 called familial platelet disorder with associated myeloid malignancy (FPDMM; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 601399).11 Additional symptoms have also been associated with FPDMM, including eczema and psoriasis.12-14RUNX1 variants may exert pathologic effects through either haploinsufficiency or dominant-negative interference with normal RUNX1 function.15 Pathogenic germ line RUNX1 variants can be of any type (eg, nonsense, missense, alternative splicing, insertions, deletions, and duplications) and have been found throughout the RUNX1 gene.8,16,17 However, no correlations have been identified between the types of RUNX1 variants and clinical phenotype.8

Predisposition to HM is a chief concern for patients, families, and health care providers. The reported lifetime incidence of HM in patients with FPDMM is between 35% and 45%, with a median age of 33 years.7,18 The most common HMs reported in patients with FPDMM are myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) and T-cell ALL (T-ALL), hairy-cell leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) have also been reported.8,19-21 The development of HMs in the setting of inherited RUNX1 variation is usually associated with the acquisition of somatic variants in HM-associated genes.22-24 Previous work suggests that somatic variants of the second RUNX1 allele are common in HMs from patients with FPDMM.8,25

Comprehensive characterization of rare disorders via deep phenotyping and genotyping can provide a better understanding of underlying pathophysiology, help optimize clinical care, and inform future research directions.26,27 We opened a prospective, longitudinal natural history study for patients with FPDMM at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center. This report describes the clinical findings of patients enrolled in the study between early 2019 and December 2021.

Methods

Patients

The protocol was approved by the NIH Institutional Review Board in January 2019 (#NCT03854318). Participants with germ line RUNX1 variants are referred to as patients, and noncarrier family members are referred to as controls. Known or suspected RUNX1 variant carriers of any age were eligible. Probands were initially identified through several subspecialty clinics (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website).

RUNX1 variants (reference sequence NM_001754.4) were confirmed with Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments [CLIA]-certified Sanger sequencing for all suspected carriers. Family members included as controls were sequenced to confirm the absence of the variant. Skin biopsy testing was conducted for cases in which it was uncertain whether the variant was germ line or somatic. All variants were classified using ClinGen criteria.28 Patients and their referring providers submitted medical records and completed medical intake questionnaires. All patients or their legal guardians gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical evaluation

Families were offered annual in-person visits at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD, and/or telehealth evaluations. History and physical examination, peripheral blood (PB) laboratory work, and bone marrow (BM) aspirate and biopsy were offered annually. The bleeding phenotype was determined by medical history and the administration of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Bleeding Assessment Tool (ISTH-BAT).29 Families opting for remote enrollment had a review of their medical history, medical records, and blood and/or BM pathology materials obtained by mail. The PB laboratory values reported are for the first in-person visit to the NIH.

BM and platelet evaluation

BM aspirates and biopsy cores were obtained from the posterior superior iliac crest. Platelets were analyzed by electron microscopy and lumiaggregometer. Healthy BM control data were provided by the Department of Laboratory Medicine at the NIH (not from the controls enrolled in our study).

See additional details in supplemental Materials.

Evaluations by other specialists

Evaluations by the gastroenterology/hepatology team, allergy/immunology team, and dermatology team, and specialists are described in supplemental Materials.

Results

Participants

Between January 2019 and December 2021, we enrolled 214 participants, including 126 with confirmed germ line RUNX1 variants and 85 familial controls without RUNX1 variants. From the 126, we excluded 15 with variants categorized as benign, likely benign, or of uncertain significance without a clinical picture consistent with FPDMM. Three families (FPD_5, FPD_8, and FPD_38) with variants of uncertain significance were included in the analysis because their RUNX1 variants cosegregated with mild/moderate thrombocytopenia plus either clinical bleeding/bruising or abnormal platelet function testing consistent with FPDMM (ie, aspirinlike defect on platelet aggregometry or decreased δ-granules on electron microscopy). This left 111 patients for analysis, together with 85 controls (supplemental Figure 2; supplemental Table 2). The demographics of the enrolled participants are listed in supplemental Table 3. These 111 patients represent 45 unrelated families (supplemental Table 4). A total of 77 patients had baseline platelet counts from either the NIH or outside hospitals (supplemental Table 2). Of these, 70 (91%) had counts below the stated reference range, consistent with existing literature that thrombocytopenia is a main feature of FPDMM. A total of 8 probands carried an initial diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) before their RUNX1 variant was found. Looking at all probands, the elapsed time between clinical evaluation for thrombocytopenia, bleeding/bruising, or malignancy and detection of their RUNX1 variants averaged 8.5 years, with a median of 6 years (supplemental Table 1).

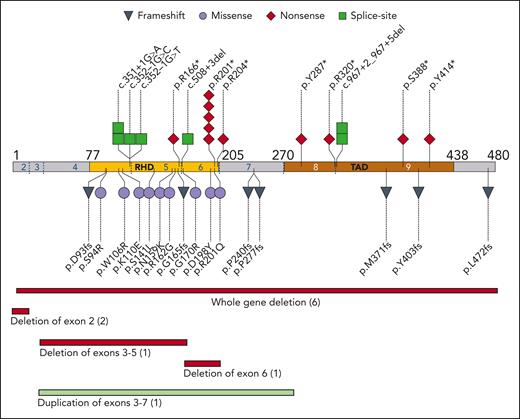

Germ line variants

The enrolled 45 families had 39 unique RUNX1 variants (Figure 1). A total of 18 families had nonsense or frameshift variants, 9 had a missense variant in the RHD domain, 10 had a partial or whole deletion of the RUNX1 locus, 7 had variants affecting splice sites, and 1 had an intragenic duplication. Two hot spots were notable: 6 families had a missense or nonsense variant at p.R201 and 4 had variants in the c.351-352 splice sites between exons 4 and 5. Although most families had multigenerational inheritance, 3 unrelated patients had RUNX1 variants that were not present in fibroblast DNA from their parents, suggestive of either de novo acquisition or germ cell mosaicism in a parent; these variants were 2 unrelated c.601C>T p.R201∗ nonsense variants and 1 c.1208_1322del frameshift variant. No revertant phenotypes were found by comparing DNA from skin fibroblasts to DNA from PB or BM.

Germ line variants in RUNX1 cohort. The pathologic or likely pathologic germ line variants aligned to NM_001754.4 coding sequence. The type of variant is coded as per the shape and color. Each shape represents one family; similarly, the number in parentheses for deletions/duplications show number of families. Amino acid residue number is indicated by black numbers; exons are indicated by blue and white numbers, with exon boundaries marked by dotted blue lines. RHD, runt homology domain; TAD, transactivation domain.

Germ line variants in RUNX1 cohort. The pathologic or likely pathologic germ line variants aligned to NM_001754.4 coding sequence. The type of variant is coded as per the shape and color. Each shape represents one family; similarly, the number in parentheses for deletions/duplications show number of families. Amino acid residue number is indicated by black numbers; exons are indicated by blue and white numbers, with exon boundaries marked by dotted blue lines. RHD, runt homology domain; TAD, transactivation domain.

Hematologic manifestations

A total of 47 patients without HM had PB laboratory studies at the NIH. As expected, the patients demonstrated decreased platelet counts compared with controls (122 × 103/μL ± 64 × 103/μL vs 253 × 103/μL ± 56 × 103/μL, mean ± standard deviation; P < .0001; Figure 2A). Of these, 11 patients had platelet counts >150 × 103/μL, but 7 of these were still less than the reference range for age and sex, leaving 4 of 47 (9%) with normal platelet counts (supplemental Table 5). Average mean platelet volume was not significantly different between patients and controls (9.9 vs 10.0 fL), though the standard deviation was increased for patients (1.2 vs 0.79; the variance F test P < .03; Figure 2B). There was also no difference in immature platelet fraction (Figure 2C), and the mean platelet volume correlated with the immature platelet fraction for both patients and controls (supplemental Figure 3A-B).

Hematologic findings and clinical bleeding severity. Comparison of laboratory values between patients and controls for platelet counts (A), mean platelet volume (B), immature platelet fraction based on the sex (C), hemoglobin (D), absolute eosinophil count (F), and ARC (G). The hemoglobin and ARC comparisons are further separated into sex categories (E) and (H), respectively, showing a statistically significant difference between the 2 male groups for hemoglobin. Patient ARC plotted vs hemoglobin values (I). ISTH-BAT scores for patients with FPDMM separated according to sex (J). Scores are further divided by the patient’s type of RUNX1 variant for adult women (K), and for adult male and children combined (L). Children are ages ≤14 years, men and women are ages ≥17 years. Dotted green lines indicate abnormal cutoff for sex/age. In panel L, the cutoff for adult males is used, which is higher than the cutoff for children. Bars in panels A-H indicate mean and 1 standard deviation. Hgb, hemoglobin.

Hematologic findings and clinical bleeding severity. Comparison of laboratory values between patients and controls for platelet counts (A), mean platelet volume (B), immature platelet fraction based on the sex (C), hemoglobin (D), absolute eosinophil count (F), and ARC (G). The hemoglobin and ARC comparisons are further separated into sex categories (E) and (H), respectively, showing a statistically significant difference between the 2 male groups for hemoglobin. Patient ARC plotted vs hemoglobin values (I). ISTH-BAT scores for patients with FPDMM separated according to sex (J). Scores are further divided by the patient’s type of RUNX1 variant for adult women (K), and for adult male and children combined (L). Children are ages ≤14 years, men and women are ages ≥17 years. Dotted green lines indicate abnormal cutoff for sex/age. In panel L, the cutoff for adult males is used, which is higher than the cutoff for children. Bars in panels A-H indicate mean and 1 standard deviation. Hgb, hemoglobin.

Hemoglobin levels were lower in patients than in controls (13.0 ± 1.4 g/dL vs 14.2 ± 1.6 g/dL; P < .002; Figure 2D). Hemoglobin was significantly lower in male patients than in male controls (13.6 vs 15.0 g/dL; P < .01), but there was no significant difference between the female groups (12.4 vs 13.0 g/dL; P = .19; Figure 2E). The absolute reticulocyte count was comparable between groups (Figure 2G-H). Three patients had a low/normal absolute reticulocyte count and a low reticulocyte production index in the setting of low hemoglobin, suggesting insufficient red cell production (Figure 2I; supplemental Figure 3J). The absolute eosinophil counts (AECs) were significantly increased in patients (0.31 × 103/μL ± 0.33 × 103/μL vs 0.15 × 103/μL ± 0.09 × 103/μL; P < .03; Figure 2F). Broken down based on sex, the mean AEC was significantly increased for female patients (0.25 × 103/μL ± 0.17 × 103/μL vs 0.12 × 103/μL ± 0.06 × 103/μL; P < .03; supplemental Figure 3C) and a subset of male patients (supplemental Table 6). Mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, RBC distribution width, and absolute monocyte counts were not significantly different between groups (supplemental Figure 3D-F,I).

To quantify bleeding symptoms, the ISTH-BAT was administered to patients, where scores ≥6 for women, ≥4 for men, and ≥3 for children were considered abnormal.29,30 Abnormal scores were noted for 50% of adult women (11 of 22), 59% of adult men (10 of 17), and 44% of children (7 of 16) and, thus, 51% (28 of 55) for patients overall (Figure 2J). Adult women with missense variants tended to have normal ISTH-BAT scores (5 of 7), but 1 notable exception was a 60-year-old woman with the RUNX1 p.G170R variant (Figure 2K). Frameshift variants tended to be associated with abnormal ISTH-BAT scores in 2 of 2 women and 4 of 6 men and children (Figure 2K-L).

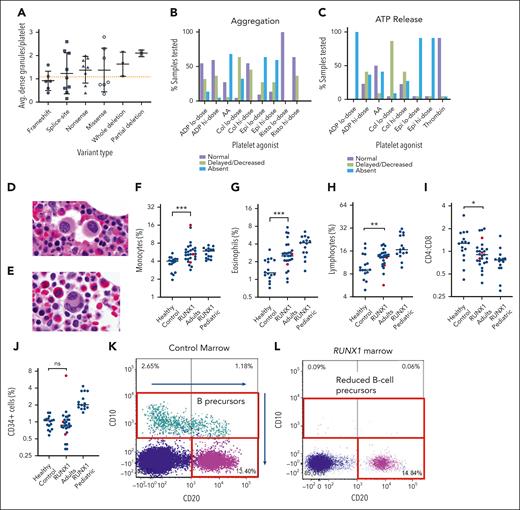

Platelets in patients with FPDMM may show a functional defect similar to an aspirin effect, and they may have α- and/or δ-granule abnormalities.31-33 In our study, 16 of 35 tested patients (46%) had decreased δ-granule averages (less than 1.2 dense granules per platelet per the laboratory’s internal reference cutoff for adults34) on platelet electron microscopy (supplemental Table 7; supplemental Figure 4). Patients with frameshift variants and variants in exons 4-5 had lower average dense granule numbers (Figure 3A). In 39 patients with α-granule testing, 27 patients (69%) had abnormal alpha granules, 6 patients (15%) had normal alpha granules, and 6 patients (15%) had alternately normal and abnormal alpha granules from different timepoints. Lumiaggregometry was performed for 18 patients (23 time points; 5 patients had second time points a year later) with pathogenic or likely pathogenic RUNX1 variants (supplemental Table 8). All 18 patients showed decreased or absent aggregation to at least some agonists (Figure 3B). Notably, abnormal platelet aggregation in response to low-dose collagen was detected in 17 of 18 patients (94%). All 18 patients demonstrated abnormal adenosine triphosphate release in response with at least some agonists (Figure 3C). Abnormal adenosine triphosphate release in response to low-dose adenosine diphosphate was noted in all 18 patients (100%). It is notable that 2 of these 18 patients with abnormal aggregometry had normal baseline platelet counts.

Platelet electron microscopy, aggregometry, and BMw evaluation. Average number of dense granules per platelet in each patient tested, compared according to the type of variant (A). Normal cutoff for adults is 1.2 granules/platelet (dotted orange line). Bars indicate mean and 1 standard deviation. Percentage of patients with normal, delayed/decreased, or absent platelet aggregation (B) and adenosine triphosphate release (C) in response to various platelet agonists. Representative BM histology of FPDMM patients showing small megakaryocytes with hypolobation (D) or separated nuclear lobes (E). BM flow cytometry analysis quantified percentage of monocytes of all nucleated cells based on expression of CD14 and CD64 (F), eosinophils of all cells based on expression of CD45, CD16 and side light scatter (G), lymphocytes of all cells based on CD45, CD3, CD19, and CD56 (H), CD4:CD8 ratios of CD3+ T cells (I), and CD34+ cells of all nucleated cells (J). Mann Whitney statistical analysis compared BM of controls (n = 16) vs FPDMM adults without malignancy (n = 24) (blue dots). Three FPDMM adults diagnosed with a myeloid malignancy (1 CMML and 2 MDS) are indicated by red dots but were not included in the statistical analysis which sought to evaluate differences in baseline (nonmalignant) patients with FPDMMvs controls. Pediatric patients with FPDMM without a malignancy were separated in the analysis as healthy pediatric controls were not available for comparison. Black horizontal lines refer to median. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Flow cytometry shows normal CD10+ B-cell precursors in a healthy marrow (K), compared with an FPDMM marrow (L) showing absence of CD10+ B-cell precursors. AA, arachidonic acid; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; Avg, average.

Platelet electron microscopy, aggregometry, and BMw evaluation. Average number of dense granules per platelet in each patient tested, compared according to the type of variant (A). Normal cutoff for adults is 1.2 granules/platelet (dotted orange line). Bars indicate mean and 1 standard deviation. Percentage of patients with normal, delayed/decreased, or absent platelet aggregation (B) and adenosine triphosphate release (C) in response to various platelet agonists. Representative BM histology of FPDMM patients showing small megakaryocytes with hypolobation (D) or separated nuclear lobes (E). BM flow cytometry analysis quantified percentage of monocytes of all nucleated cells based on expression of CD14 and CD64 (F), eosinophils of all cells based on expression of CD45, CD16 and side light scatter (G), lymphocytes of all cells based on CD45, CD3, CD19, and CD56 (H), CD4:CD8 ratios of CD3+ T cells (I), and CD34+ cells of all nucleated cells (J). Mann Whitney statistical analysis compared BM of controls (n = 16) vs FPDMM adults without malignancy (n = 24) (blue dots). Three FPDMM adults diagnosed with a myeloid malignancy (1 CMML and 2 MDS) are indicated by red dots but were not included in the statistical analysis which sought to evaluate differences in baseline (nonmalignant) patients with FPDMMvs controls. Pediatric patients with FPDMM without a malignancy were separated in the analysis as healthy pediatric controls were not available for comparison. Black horizontal lines refer to median. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001. Flow cytometry shows normal CD10+ B-cell precursors in a healthy marrow (K), compared with an FPDMM marrow (L) showing absence of CD10+ B-cell precursors. AA, arachidonic acid; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; Avg, average.

BM evaluation

Evaluation of BM biopsies and aspirates from 55 patients was performed at NIH, including 24 adults and 21 pediatric patients without malignancy and 7 adult and 3 pediatric patients with malignancy (Table 1). Of the nonmalignant adult marrows, 54.2% were hypocellular for age and 45.5% were normocellular. In contrast, 81% of the nonmalignant pediatric marrows were hypocellular. Of the nonmalignant marrows, 20.8% showed an increased number of megakaryocytes. Of the nonmalignant marrows, 95.8% had some degree (>10%) of megakaryocytic atypia with features of dysmegakaryopoiesis, including small hypolobated megakaryocytes, some with eccentric nuclei or separated nuclear lobes (Figure 3D-E), consistent with previous reports.35,36 Only 3 of 21 pediatric patients had decreased numbers of megakaryocytes. Variability in megakaryocyte quantity is previously described in FPDMM.35-37 In the patients without overt myeloid neoplasia, aside from megakaryocytic atypia and hypocellularity, there was normal trilineage hematopoiesis and no increase in blasts or overt dysplasia in myeloid or erythroid precursors. Focally increased eosinophils were found in 13% of marrows. Of the 10 cases with evidence of neoplasia in the marrow, there were 3 MDS (MDS with mutated SF3B1, MDS with excess blasts, and MDS not otherwise specified with single lineage dysplasia), 1 CMML, 3 AML, 1 B-ALL, 1 T-ALL, and 1 smoldering multiple myeloma diagnoses. Most malignant cases had hypercellular marrows and multilineage dysplasia, which were not seen in the nonmalignant cases. In addition, 2 cases of MDS diagnosed by outside institutions and later referred to the NIH did not subsequently meet criteria for MDS,6 because the only atypical finding was dysmegakaryopoiesis, which is a baseline finding for patients with FPDMM.

BM histologic features of patients with FPDMM

| . | All (N = 55) . | Adult (n = 24) nonmalignant . | Pediatric (n = 21) nonmalignant . | Adult malignant (n = 7) . | Pediatric malignant (n = 3) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marrow cellularity | |||||

| Hypercellular | 7 (12.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (57.1%) 1 CMML, 1 MDS, and 2 AML | 3 (100%) 1 T-ALL, 1 B-ALL, and 1 AML |

| Hypocellular | 30 (54.5%) | 13 (54.2%) | 17 (81%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Normocellular | 18 (32.7%) | 11 (45.8%) | 4 (19.0%) | 3 (42.9%) 1 SMM and 2 MDS | 0 (0%) |

| Megakaryocyte quantity | |||||

| Normal number | 30 (54.5%) | 18 (75%) | 9 (42.9%) | 3 (42.9%) 1 SMM and 2 MDS | 0 (0%) |

| Increased number | 12 (21.8%) | 5 (20.8%) | 4 (19.0%) | 3 (42.9%) 1 CMML, 1 AML, and 1 MDS | 0 (0%) |

| Decreased number | 7 (12.7%) | 0 | 3 (14.3%) | 1 (14.3%) 1 AML | 3 (100%) 1 T-ALL, 1 B-ALL, and 1 AML |

| Dysmegakaryopoiesis | 42 (76.4%) | 23 (95.8%) | 14 (66.7%) | 5 (71.4%) 3 MDS and 2 AML | NE |

| Multilineage dysplasia | 3 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (42.9%) 1 CMML, 1 AML, and 1 MDS | NE |

| Increased blasts (5%-19%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.6%) 1 CMML and 1 MDS | 0 |

| Increased blasts (>20%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.6%) 2 AML | 3 (100%) 1 T-ALL, 1-B-ALL, and 1 AML |

| BM diagnosis | |||||

| Nonmalignant | 45 (81.8%) | 24 | 21 | ||

| MDS | 3 (5.5%) | 3 (42.9%) | |||

| AML | 3 (5.5%) | 2 (28.6%) | 1 (33.3%) | ||

| CMML | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (14.3%) | |||

| T-ALL | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (33.3%) | |||

| B-ALL | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (33.3%) | |||

| SMM | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (14.3%) |

| . | All (N = 55) . | Adult (n = 24) nonmalignant . | Pediatric (n = 21) nonmalignant . | Adult malignant (n = 7) . | Pediatric malignant (n = 3) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marrow cellularity | |||||

| Hypercellular | 7 (12.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (57.1%) 1 CMML, 1 MDS, and 2 AML | 3 (100%) 1 T-ALL, 1 B-ALL, and 1 AML |

| Hypocellular | 30 (54.5%) | 13 (54.2%) | 17 (81%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Normocellular | 18 (32.7%) | 11 (45.8%) | 4 (19.0%) | 3 (42.9%) 1 SMM and 2 MDS | 0 (0%) |

| Megakaryocyte quantity | |||||

| Normal number | 30 (54.5%) | 18 (75%) | 9 (42.9%) | 3 (42.9%) 1 SMM and 2 MDS | 0 (0%) |

| Increased number | 12 (21.8%) | 5 (20.8%) | 4 (19.0%) | 3 (42.9%) 1 CMML, 1 AML, and 1 MDS | 0 (0%) |

| Decreased number | 7 (12.7%) | 0 | 3 (14.3%) | 1 (14.3%) 1 AML | 3 (100%) 1 T-ALL, 1 B-ALL, and 1 AML |

| Dysmegakaryopoiesis | 42 (76.4%) | 23 (95.8%) | 14 (66.7%) | 5 (71.4%) 3 MDS and 2 AML | NE |

| Multilineage dysplasia | 3 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (42.9%) 1 CMML, 1 AML, and 1 MDS | NE |

| Increased blasts (5%-19%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.6%) 1 CMML and 1 MDS | 0 |

| Increased blasts (>20%) | 5 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.6%) 2 AML | 3 (100%) 1 T-ALL, 1-B-ALL, and 1 AML |

| BM diagnosis | |||||

| Nonmalignant | 45 (81.8%) | 24 | 21 | ||

| MDS | 3 (5.5%) | 3 (42.9%) | |||

| AML | 3 (5.5%) | 2 (28.6%) | 1 (33.3%) | ||

| CMML | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (14.3%) | |||

| T-ALL | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (33.3%) | |||

| B-ALL | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (33.3%) | |||

| SMM | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (14.3%) |

SMM, smoldering multiple myeloma.

Flow cytometry analysis was performed on marrows of 24 adult patients without myeloid malignancy, 3 adult patients with myeloid malignancy (2 CMML and 1 MDS), 15 pediatric patient marrows without malignancy, and 16 healthy adult controls. When comparing adult patient marrows (nonmalignant) with adult control marrows, several differences were detected (Figure 3F-J; supplemental Figure 5, black dots). Adult patient marrows had increased monocytes (5.05% vs 3.95% [P = .0019]; Figure 3F), eosinophils (2.73% vs 1.29% [P = .013]; Figure 3G), and lymphocytes (13.80 vs 9.03% [P = .029]; Figure 3H). In addition, the CD4:CD8 ratio was reduced (Figure 3I). Findings of a paucity of B-cell precursors by flow cytometry were seen in a subset of patients (supplemental Figure 5D; Figure 3K-L; supplemental Table 9): 10 adults and 1 child at baseline health as well as 2 adults with hematologic neoplasms (CMML and MDS). The number of CD34+ cells was not significantly different between patients and controls, except for 1 patient with CMML who had increased blasts (Figure 3J). The 2 MDS cases analyzed did not have increased blasts.

Flow cytometric cell counts from our pediatric patient marrows were compared with published pediatric normal values.38-41 Eosinophil percentages were elevated compared with the 2.3% to 2.8% medians and 0.6% to 4.9% range reported for healthy marrows, for age <18 years40 (Figure 3G). Monocytes,40 mature CD20+ B cells,38,40,42 natural killer cells,43,44 and T-lymphocyte CD4:CD8 ratios44-46 were all comparable with the literature reference ranges (Figure 3F,I; supplemental Figure 5B-C). Such comparisons were limited because of the methodological and analytic differences.

All 55 patients had chromosome karyotyping performed from BM; 1 patient (without malignancy) initially had a small marker chromosome of unclear significance, but its frequency decreased in 3 subsequent BM samples. The patient with smoldering myeloma had a normal karyotype, but fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) testing with probes targeting plasma cell neoplasms found clonal populations with a 14q32/IGH translocation (34 of 50 cells) and a t(11;14) CCND1-IGH fusion (40 of 50 cells). Two patients with MDS had a 5q deletion on FISH that was not captured on cytogenetics. Three patients with myeloid malignancies had a complex karyotype, including t(11;19), and the patient with B-ALL had a EBF1-PDGFRB fusion detected by sequencing but missed by FISH.

Hematologic malignancies

A total of 19 patients had a history of past or present HM (Table 2). Adult HMs included 4 MDS, 6 AML, 2 CMML, and 1 smoldering myeloma (1 patient initially diagnosed with CMML progressed to AML). The pediatric HMs (<18 years) included 4 AML, 1 Philadelphia chromosome–like B-ALL, and 1 T-ALL. All patients except for the 1 with smoldering myeloma had been referred for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT; supplemental Table 10). Of these, 14 had completed at least 1 HSCT. One patient (FPD_10.4) needed a second transplant because of graft failure. One patient (FPD_68.1) had a relapse of AML after transplant.

Hematologic malignancies past and present in enrolled patients

| Patient . | Age at HM Dx (y) . | Sex . | RUNX1 variant DNA (NM_001754.4 or NC_000021) . | Variant type . | RUNX1 variant amino acid (NP_001745.2) . | Malignancy . | Somatic variants/cytogenetics . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPD_53.1 | 34 | M | g.(?_36193766)_(36265301_?)dup | Large duplication | MDS-EB | ||

| FPD_42.4 | 71 | F | g.(?_36252569)_(36265636_?)del | Partial deletion | MDS with mutated SF3B1 | EZH2, SF3B1, NF1, SH2B2 | |

| FPD_10.4 | 50 | M | c.861C>A | Nonsense | p.Y287∗ | MDS NOS-SLD | 45,X,-Y,del(11)(q14q25)[5]/46,XY[15]. nuc ish 11q23(MLLx1)[14/200] |

| FPD_50.1 | 38 | M | g.(?_ 35734654)_( 36422677 _?)del | Whole deletion | MDS | 48,XY,+Y,+21[1]/46,XY[8]. nuc ish 11q23(5′MLLx2,3′MLLx1)(5′MLL con 3′MLLx1)[42/200] | |

| FPD_52.9 | 25 | M | c.601C>T | Nonsense | p.R201∗ | MDS | |

| FPD_35.1 | 42 | M | c.1242C>G | Nonsense | p.Y414∗ | AML with myelodysplasia-related gene mutations; progressing from MDS | BCOR, PHF6, U2AF1 46,XY[7].nuc ish 5q31(EGR1x1)[14/200] |

| FPD_14.3 | 56 | M | c.1412_1413dup | Frameshift | p.L472fs | AML NOS progressing from MDS | |

| FPD_60.1 | 52 | M | c.830delC | Frameshift | p.P277Hfs∗34 | AML NOS progressing from MDS | GATA2 |

| FPD_29.5 | 47 | F | c.484A>G | Missense | p.R162G | AML NOS | 92,XXXX,add(2)(q12),idic(17)(q11.2)[6] |

| FPD_17.1 | 45 | F | c.352-1G>T | Splice site | AML NOS progressing from MDS | ||

| FPD_10.9 | 12 | F | c.861C>A | Nonsense | p.Y287∗ | AML NOS | |

| FPD_10.6 | 19 | M | c.861C>A | Nonsense | p.Y287∗ | AML NOS | 51,XY,+4,+8,+9,t(11;19),+13,del19,+21 |

| FPD_68.1 | 8 | F | c.602G>A | Missense | p.R201Q | AML NOS | KRAS G13D |

| FPD_52.14 | 8 | F | c.601C>T | Nonsense | p.R201∗ | AML NOS | |

| FPD_42.1 | 63 | M | g.(?_36252569)_(36265636_?)del | Partial deletion | CMML | JAK2 V617F, ASXL1, and SRSF2 | |

| FPD_12.1 | 58 | F | c.508+3del | Splice site | CMML progressing from MDS | BCOR, PHF6, KMT2D, NRAS, KRAS, SUZ12, CCND2, and SLX4 46,XX[20].ish del(5)(q31q31)(EGR1-)[3] | |

| FPD_23.2 | 17 | M | c.719del | Frameshift | p.P240Hfs∗14 | B-ALL with PDGFRB rearrangement | 46,XY[20]. FISH-negative result EBF1-PDGRFB fusion by sequencing |

| FPD_49.1 | 2 | M | g.(?_35423737)_(37592741_?)del | Whole deletion | T-ALL, NOS | MARS 46,XY,der(5)t(5;13)(q23;q14),del(11)(q13q23)[8]/47,idem,+19[3]/46,XY[10] | |

| FPD_5.2 | 73 | F | c.477T>G | Missense | p.N159K | Smoldering myeloma | 46,XX[20].nuc ish 11q13(CCND1-XT),14q32(IGH-XT))x3 (CCND1-XT con IGH-XTx2)[40/50] |

| Patient . | Age at HM Dx (y) . | Sex . | RUNX1 variant DNA (NM_001754.4 or NC_000021) . | Variant type . | RUNX1 variant amino acid (NP_001745.2) . | Malignancy . | Somatic variants/cytogenetics . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPD_53.1 | 34 | M | g.(?_36193766)_(36265301_?)dup | Large duplication | MDS-EB | ||

| FPD_42.4 | 71 | F | g.(?_36252569)_(36265636_?)del | Partial deletion | MDS with mutated SF3B1 | EZH2, SF3B1, NF1, SH2B2 | |

| FPD_10.4 | 50 | M | c.861C>A | Nonsense | p.Y287∗ | MDS NOS-SLD | 45,X,-Y,del(11)(q14q25)[5]/46,XY[15]. nuc ish 11q23(MLLx1)[14/200] |

| FPD_50.1 | 38 | M | g.(?_ 35734654)_( 36422677 _?)del | Whole deletion | MDS | 48,XY,+Y,+21[1]/46,XY[8]. nuc ish 11q23(5′MLLx2,3′MLLx1)(5′MLL con 3′MLLx1)[42/200] | |

| FPD_52.9 | 25 | M | c.601C>T | Nonsense | p.R201∗ | MDS | |

| FPD_35.1 | 42 | M | c.1242C>G | Nonsense | p.Y414∗ | AML with myelodysplasia-related gene mutations; progressing from MDS | BCOR, PHF6, U2AF1 46,XY[7].nuc ish 5q31(EGR1x1)[14/200] |

| FPD_14.3 | 56 | M | c.1412_1413dup | Frameshift | p.L472fs | AML NOS progressing from MDS | |

| FPD_60.1 | 52 | M | c.830delC | Frameshift | p.P277Hfs∗34 | AML NOS progressing from MDS | GATA2 |

| FPD_29.5 | 47 | F | c.484A>G | Missense | p.R162G | AML NOS | 92,XXXX,add(2)(q12),idic(17)(q11.2)[6] |

| FPD_17.1 | 45 | F | c.352-1G>T | Splice site | AML NOS progressing from MDS | ||

| FPD_10.9 | 12 | F | c.861C>A | Nonsense | p.Y287∗ | AML NOS | |

| FPD_10.6 | 19 | M | c.861C>A | Nonsense | p.Y287∗ | AML NOS | 51,XY,+4,+8,+9,t(11;19),+13,del19,+21 |

| FPD_68.1 | 8 | F | c.602G>A | Missense | p.R201Q | AML NOS | KRAS G13D |

| FPD_52.14 | 8 | F | c.601C>T | Nonsense | p.R201∗ | AML NOS | |

| FPD_42.1 | 63 | M | g.(?_36252569)_(36265636_?)del | Partial deletion | CMML | JAK2 V617F, ASXL1, and SRSF2 | |

| FPD_12.1 | 58 | F | c.508+3del | Splice site | CMML progressing from MDS | BCOR, PHF6, KMT2D, NRAS, KRAS, SUZ12, CCND2, and SLX4 46,XX[20].ish del(5)(q31q31)(EGR1-)[3] | |

| FPD_23.2 | 17 | M | c.719del | Frameshift | p.P240Hfs∗14 | B-ALL with PDGFRB rearrangement | 46,XY[20]. FISH-negative result EBF1-PDGRFB fusion by sequencing |

| FPD_49.1 | 2 | M | g.(?_35423737)_(37592741_?)del | Whole deletion | T-ALL, NOS | MARS 46,XY,der(5)t(5;13)(q23;q14),del(11)(q13q23)[8]/47,idem,+19[3]/46,XY[10] | |

| FPD_5.2 | 73 | F | c.477T>G | Missense | p.N159K | Smoldering myeloma | 46,XX[20].nuc ish 11q13(CCND1-XT),14q32(IGH-XT))x3 (CCND1-XT con IGH-XTx2)[40/50] |

All RUNX1 variants are described using the NM_001754.5, NP_001745.2, and NC_000021.

Dx, diagnosis; F, female; M, male; MDS NOS-SLD, MDS, not otherwise specified, with single lineage dysplasia; MDS-EB, MDS with excess blasts.

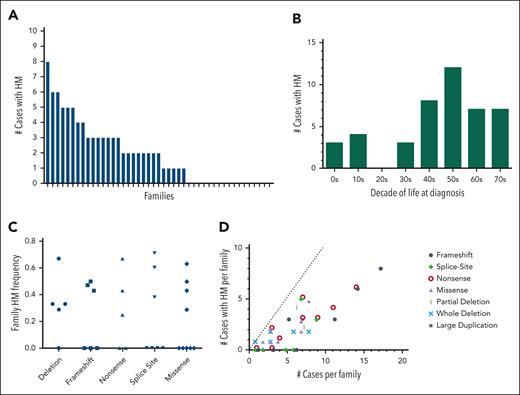

Using the family history data reported by the patients, we tallied the total number of potential FPDMM cases for each family (supplemental Table 4, column 2). This case count included both enrolled patients and family members (alive or dead) suspected to have had FPDMM based on a report of thrombocytopenia, bleeding history, or hematologic malignancy and in accordance with Mendelian inheritance. Out of 45 families, 28 (62%) had at least 1 case with HM, and 15 of 45 of the families (33%) had 3 or more cases with HM (Figure 4A). For those cases that had age of diagnosis data, the average age of HM diagnosis was 46 years, with a median of 48.5 years and a range of 6 to 77 years (Figure 4B). HM frequencies were calculated for each family by taking the number of cases with HMs (supplemental Table 4, column 3) and dividing it by the total number of cases in that family. These family HM frequencies did not correlate with the RUNX1 variant type (Figure 4C). Of the 6 families with p.Arg201 hot spot variants, all 4 families with more than 1 case had at least 1 HM, whereas the 2 patients who were the only cases in their respective families (FPD_15.1 and FPD_48.1, aged 8 and 4 years, respectively) had not developed HM. Notably, 3 of the 4 families with a c.351+1 or c.352–1 splicesite variant had a history of HM. Taking family sizes into account, the larger families with frameshift and nonsense variants roughly follow the expected linear relationship; the smaller families had noisier frequencies (Figure 4D). All 17 large families with 7 or more cases had at least 1 HM (in fact, each had 2 or more).

Familial hematologic malignancy frequency in the FPDMM cohort. (A) Histogram showing the number of cases of HM malignancy by history in each of the 47 enrolled families. Cases were counted only if they were of a person who was suspected to have FPDMM and could have had the RUNX1 variant according to Mendelian inheritance. Cases included deceased family members and members not enrolled in the study. The families are sorted as decreasing numbers of cases. (B) Bar graph showing number of cases with HM for each decade of life in which the HM was initially diagnosed. Only cases that had age of diagnosis data available were included. (C) Frequency of HM organized by type of RUNX1 variant. Each data point represents the frequency for a single family, in which the denominator is the number of potential FPDMM cases in the family (supplemental Table 4, column 2) and the numerator is the number of cases with HM (supplemental Table 4, column 3). (D) A scatterplot showing the relationship of number of hematologic malignancies to the size of the family for the different variant types. Each data point represents 1 family, in which the x-coordinate is the number of FPDMM cases in the family, and the y-coordinate is the number of cases with hematologic malignancy reported for that family (enrolled and historical). The dotted line shows a theoretical 100% penetrance for HM. Larger families are predicted to have more cases than smaller families.

Familial hematologic malignancy frequency in the FPDMM cohort. (A) Histogram showing the number of cases of HM malignancy by history in each of the 47 enrolled families. Cases were counted only if they were of a person who was suspected to have FPDMM and could have had the RUNX1 variant according to Mendelian inheritance. Cases included deceased family members and members not enrolled in the study. The families are sorted as decreasing numbers of cases. (B) Bar graph showing number of cases with HM for each decade of life in which the HM was initially diagnosed. Only cases that had age of diagnosis data available were included. (C) Frequency of HM organized by type of RUNX1 variant. Each data point represents the frequency for a single family, in which the denominator is the number of potential FPDMM cases in the family (supplemental Table 4, column 2) and the numerator is the number of cases with HM (supplemental Table 4, column 3). (D) A scatterplot showing the relationship of number of hematologic malignancies to the size of the family for the different variant types. Each data point represents 1 family, in which the x-coordinate is the number of FPDMM cases in the family, and the y-coordinate is the number of cases with hematologic malignancy reported for that family (enrolled and historical). The dotted line shows a theoretical 100% penetrance for HM. Larger families are predicted to have more cases than smaller families.

Allergy and immunology

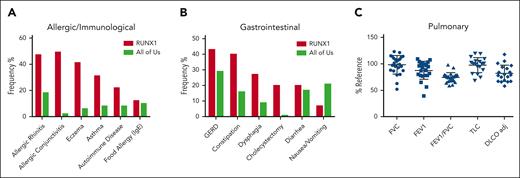

A group of 45 consecutive patients (19 female) with germ line RUNX1 variants and a median age of 36 years (interquartile range, 12-53 years) were prospectively evaluated by the allergy/immunology team. A total of 3 male and 2 female patients were evaluated after undergoing HSCT for AML. Out of 45, 42 patients (93%) had at least 1 doctor-diagnosed allergic disorder, with allergic rhinitis (33 of 45; 73%) being the most common, followed by eczema (20 of 45; 44%), allergic conjunctivitis (17 of 45; 38%), and asthma (14 of 45; 31%; Figure 5A; supplemental table 11). Of those with allergic rhinitis, 3 were monosensitized and 21 polysensitized to environmental allergens. The frequency of all these conditions in our cohort was higher than the rates self-reported in the AllofUs database.47 Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated food allergy, confirmed by clinical history and positive skin prick and/or serum food-specific IgE testing, was identified in 5 of 45 patients (11%). Food-pollen syndrome, manifesting as oral pruritus after eating specific foods because of cross-reactive allergens present in pollen and raw fruits and vegetables, was noted in 6 of 45 patients (13%). All patients with food-pollen syndrome had allergic rhinitis and were sensitized to either birch pollen or ragweed pollen. Of the 45 patients evaluated, 2 had been previously diagnosed with eosinophilic esophagitis, 4 with acute intermittent urticaria, and 3 with venom anaphylaxis. Although the overall prevalence of allergic disorders increased in FPDMM, few cases were severe or refractory to treatment. No correlation was found between rhinitis or eczema and AEC (supplemental Figure 3G-H). PB immunoglobulin and tryptase levels are shown in supplemental Figure 6.

Nonhematologic manifestations of FPDMM. (A) The prevalence of allergic/immunologic symptoms in 45 consecutive patients prospectively evaluated by the NIH allergy/immunology clinic team. (B) The prevalence of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in 30 consecutive patients prospectively evaluated by the NIH GI clinical team. The number of patients with FPDMM is compared with the prevalence in the NIH All of Us database in both panels A and B. (C) Pulmonary function testing results for patients. The y-axis is percentage of reference value. Horizontal bars indicate mean and standard deviation. DLCO adj, adjusted diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung capacity.

Nonhematologic manifestations of FPDMM. (A) The prevalence of allergic/immunologic symptoms in 45 consecutive patients prospectively evaluated by the NIH allergy/immunology clinic team. (B) The prevalence of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in 30 consecutive patients prospectively evaluated by the NIH GI clinical team. The number of patients with FPDMM is compared with the prevalence in the NIH All of Us database in both panels A and B. (C) Pulmonary function testing results for patients. The y-axis is percentage of reference value. Horizontal bars indicate mean and standard deviation. DLCO adj, adjusted diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung capacity.

Gastroenterology

A total of 30 consecutive patients were evaluated by the gastroenterology team (supplemental Table 12). Gastroesophageal reflux was the most common history reported (13 of 30; 43%), followed by constipation (12 of 30; 40%), dysphagia (8 of 30; 27%), cholecystectomy (6 of 30; 20%), diarrhea (6 of 30; 20%), nausea, and/or vomiting (2 of 30; 7%; Figure 5B). A total of 24 of 30 (80%) had 1 or more of these symptoms. Out of 7 patients who underwent barium swallow studies, 2 had detectable abnormalities: oral dysphagia in a mother and poor esophageal motility in her daughter, both with p.N159K variants.48

Four patients underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy for dysphagia. For those with esophageal biopsies, none met the criteria for active eosinophilic esophagitis at NIH. One patient with hematochezia was endoscopically normal. No patients experienced bleeding complications at NIH after endoscopy.

Pulmonology

Pulmonary function tests were performed at the NIH Clinical Center Pulmonary Function Laboratory on 29 patients (supplemental Table 13), 5 of whom were evaluated after HSCT (highlighted in yellow). The data for the 24 patients who never underwent transplantation are shown in Figure 5C. Of these, 9 patients demonstrated an obstructive pattern on spirometry, 2 had a restrictive ventilatory defect based on lung volume measurement, and 13 had a diffusion capacity (adjusted for hemoglobin levels) <80% predicted. Nine of the patients had a diagnosis of sleep apnea, prompting continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) usage.

Dermatology

Among 30 patients evaluated by the dermatology team, most reported a history of skin problems (29 of 30; 97%). A history of eczema was reported in 11 of 30 (37%). Out of 30, 7 (23%) had active eczema at the time of evaluation, 4 of whom were boys under the age of 12 years. The most frequently reported skin finding was bruising (22 of 30; 73%). Other findings on examination included nevi, lentigines, keratosis pilaris, alopecia areata, molluscum contagiosum, verruca vulgaris, seborrheic keratosis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and epidermal inclusion cysts.

Discussion

Here, we report the largest, prospective, single-center cohort of patients with germ line RUNX1 variants. The 39 RUNX1 variants span the coding sequence, covering all reported variant types associated with FPDMM (supplemental Figure 7). Common findings include splicesite variants between exons 4 and 5, variants involving the p.R201 hot spot, and large genomic rearrangements (including deletions and duplications). These findings highlight the need for analysis of all exons and introns as well as copy number to ensure accurate detection of RUNX1 variants, as has been called for in diagnostic guidelines and previous literature.8,25,28 Our data do not yet show a correlation of cancer risk with particular RUNX1 variants, but longer follow-up, a growing cohort size, and analysis of data at the level of gene expression may reveal such correlations.

Our data show that a high degree of suspicion may be necessary to diagnose cases of FPDMM. Although lifelong mild or moderate thrombocytopenia is a core feature of the FPDMM phenotype, 9% of the patients in our cohort had normal platelet counts. Of the patients evaluated with an ISTH-BAT, about only half had an abnormal score. As a result, neither normal platelet counts nor an absence of clinically appreciable bleeding can rule out FPDMM. It took an average of 7 years for each proband to receive a correct diagnosis. Conversely, for patients who did have a history of bleeding and bruising, even to the point of requiring platelet transfusions or antifibrinolytics, diagnosis could elude them for decades. A total of 11 of our patients (8 probands) initially received a diagnosis of ITP. All 18 patients tested with platelet aggregometry had abnormal response patterns, including 2 patients with baseline platelet counts normal for their age.

BM evaluation showed the presence of dysmegakaryopoiesis in 76% of patients. Our results were consistent with previous reports noting >5% atypical megakaryocytes in most marrow evaluations35 and fit mechanistic studies demonstrating low ploidy levels in megakaryocytes in patients with FPDMM.49 These findings suggest that atypical megakaryocytes or dysmegakaryopoiesis are common features of FPDMM. However, megakaryocytic atypia is nonspecific and can be seen with germ line variants in other genes associated with inherited platelet disorders and hematologic malignancies, such as ETV6 and ANKRD26.4 Caution is also recommended not to overdiagnose MDS in patients with germ line RUNX1 variants based solely on isolated thrombocytopenia and megakaryocytic atypia. The numbers of megakaryocytes may be variable, and increased numbers should not be confused with ITP. Half of the adult and 85% of the pediatric patients without HM in our study had hypocellular marrows for age, supporting the possibility that a hypocellular stage may precede the hypercellular stage in neoplastic transformation in FPDMM.4,36

Symptoms of asthma and eczema have been previously described for FPDMM. As expected, there is a subset of the NIH FPDMM population with a strong atopic phenotype. The AECs in the total patient population were significantly higher than in the controls. We found that elevated IgE levels and PB eosinophil counts did not generally segregate with RUNX1 variant type, but there was a subset of patients with splicesite and frameshift variants that did have elevated IgE levels. Additionally, we have expanded the potential FPDMM clinical spectrum to include diseases of GI tract motility (particularly gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD], constipation, and dysphagia).

This study is not without limitations. There is likely an ascertainment bias in this cohort. Almost all probands were referred to the study after their germ line RUNX1 variants had been detected and/or FPDMM had already been diagnosed, risking overrepresentation of patients with a more severe clinical phenotype or those with better access to medical care. To mitigate this, cascade testing of family members allows us to find and evaluate patients with milder presentations. Though the cost of evaluation and travel is covered by the study, clinical evaluation at the NIH Clinical Center requires participants to take significant time and is not accessible to all. Efforts are underway to recruit more patients through large population cohorts and more underrepresented populations to better assess the true landscape of FPDMM. Remote patient evaluation will also improve study recruitment and accessibility.

This study allows for deep genotyping, phenotyping, and biobanking at repeat time points over potentially decades of follow-up, including documenting novel findings not previously associated with FPDMM. Given the high lifetime risk of HM in this population, a longitudinal protocol may enable us to study transitions from patients’ baseline BMs to clonal hematopoiesis to overt neoplasm to create a validated, individualized risk score for malignant transformation. A risk score could inform personalized and holistic care, including optimizing the timing of preventive and/or therapeutic interventions such as targeted small molecules or early HSCT.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to patients and their family members for their participation in this clinical study as well as the many referring providers. The authors are also grateful to Joy Bryant, Jose Salas, Jocelyn Ruiz Diaz for their work as patient care coordinators to help arrange travel to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center. The authors thank the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center, NIH National Human Genome Research Institute Genomics, Microarray, Bioinformatics, Cytogenetics Cores, and NIH National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Genomic Technology Section for generating genomic data. The authors thank the NIH Clinical Center for conducting all clinical procedures, pathology evaluations, and laboratory tests. We thank the RUNX1 Research Program, a patient advocacy nonprofit, for their help with recruiting study subjects and for travel support for international patients.

This work was supported by the intramural research programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Cancer Institute, Clinical Center, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: L.C. and P.P.L. developed the clinical protocol for NCT03854318; M.M. performed the clinical and hematologic data analysis and drafted the manuscript; L.C., M.M., N.T.D., S.C., K.O., D.J.Y., and K.C. performed longitudinal clinical evaluation at the NIH. K.R.C., R.B., A.D.-F., N.P., and K.N. performed the BM evaluations; K.R.C., N.O., and S.D.L. analyzed the BM data; L.C. compiled the referral and prior diagnosis data; L.C., M.M., and E.J.A. compiled hematologic malignancy and transplant data; K.Y. performed genetic sequence analysis; N.D., J. Davis, L.C., M.M., K.C., and S.C. acquired medical and family history and enrolled patients; J.N. and S.R. performed and reported CLA-certified RUNX1 genotyping; A.D.-F. and N.P. performed the platelet aggregometry; K.S. and P.A.F.-G. performed allergy/immunology evaluations and data analysis; S.B., M.P., and T.H. performed gastroenterology evaluations and data analysis; L.H. and E.W.C. performed dermatology evaluation, data analysis, and skin biopsies; L.C., E.J.A., and M.M. compiled ISTH-BAT scores; M.M., K.Y., E.B., J. Diemer, J. Davis, L.C., and K.C. acquired patient samples; M.M., K.Y., J. Diemer, E.B. processed patient samples; A.B. and K.R. performed pulmonary evaluation with pulmonary function testing; L.C. was the medical director; P.P.L. was the protocol principal investigator who supervised the project; and all authors discussed and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paul Liu, NHGRI, National Institutes of Health, 50 South Dr, Bldg 50, Room 5222C, Bethesda, MD 20892; email: pliu@mail.nih.gov.

References

Author notes

∗L.C. and M.M. contributed equally to this study.

A database of de-identified clinical and genomic data for each patient will be set up soon after publication. Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Paul Liu (pliu@nih.gov).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal