EBNA2 reduces ICOSL expression in B-cell lymphoma such as DLBCL through miR-24.

Silencing of miR-24 reconstitutes tumor immunogenicity and induces apoptosis in DLBCL.

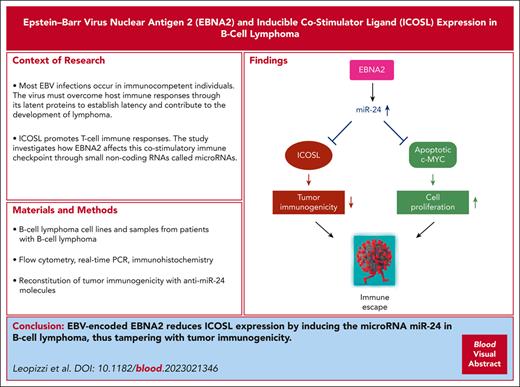

Visual Abstract

Hematological malignancies such as Burkitt lymphoma (BL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cause significant morbidity in humans. A substantial number of these lymphomas, particularly HL and DLBCLs have poorer prognosis because of their association with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Our earlier studies have shown that EBV-encoded nuclear antigen (EBNA2) upregulates programmed cell death ligand 1 in DLBCL and BLs by downregulating microRNA-34a. Here, we investigated whether EBNA2 affects the inducible costimulator (ICOS) ligand (ICOSL), a molecule required for efficient recognition of tumor cells by T cells through the engagement of ICOS on the latter. In virus-infected and EBNA2-transfected B-lymphoma cells, ICOSL expression was reduced. Our investigation of the molecular mechanisms revealed that this was due to an increase in microRNA-24 (miR-24) by EBNA2. By using ICOSL 3′ untranslated region–luciferase reporter system, we validated that ICOSL is an authentic miR-24 target. Transfection of anti–miR-24 molecules in EBNA2-expressing lymphoma cells reconstituted ICOSL expression and increased tumor immunogenicity in mixed lymphocyte reactions. Because miR-24 is known to target c-MYC, an oncoprotein positively regulated by EBNA2, we analyzed its expression in anti–miR-24 transfected lymphoma cells. Indeed, the reduction of miR-24 in EBNA2-expressing DLBCL further elevated c-MYC and increased apoptosis. Consistent with the in vitro data, EBNA2-positive DLBCL biopsies expressed low ICOSL and high miR-24. We suggest that EBV evades host immune responses through EBNA2 by inducing miR-24 to reduce ICOSL expression, and for simultaneous rheostatic maintenance of proproliferative c-MYC levels. Overall, these data identify miR-24 as a potential therapeutically relevant target in EBV-associated lymphomas.

Introduction

It is estimated that globally ∼240 000 to 350 000 new cases of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–associated cancers occur annually.1 A significant proportion of them are hematological malignancies such as Burkitt lymphoma (BL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and other lymphomas arising in immunocompromised hosts such as recipients of transplantation or individuals with HIV infection.2,3 Among these lymphomas, the most frequent association of EBV is with the endemic form of BL, a tumor very common in sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed, almost all endemic forms of BL carry EBV. BL is also considered the fastest growing human tumor.4,5

DLBCL is the most frequent non-HL and up to 10% of cases are associated with EBV in immunocompetent patients.6 The viral association with DLBCL reaches >90% when the immune system is jeopardized.1 With gene expression profiling technologies, DLBCLs have been broadly divided into 2 categories, namely the germinal center (GC) type or the activated B-cell (ABC) type.7-9 Protein expression–based algorithms suggest that EBV is more frequently associated with ABC-type DLBCLs, and EBV/EBV-encoded nuclear antigen (EBNA2)–positive DLBCLs have a very poor prognosis.10,11 However, a more recent comprehensive study based on gene expression analysis in primary central nervous system lymphomas suggests that EBV association with ABC DLBCL may be lower.12 Interestingly, EBNA2 expression is also associated with drug resistance in DLBCL.13

Worldwide, >95% of the human population is EBV seropositive.14 To establish latency, the virus encodes 6 nuclear antigens (EBNA1-6); 3 membrane proteins, latent membrane protein (LMP)1, 2A, and 2B; and a set of noncoding RNAs comprising Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNAs (EBERs) and viral microRNAs (miRNAs).15 The latent viral gene expression is divided into 3 main latency types. EBNA1 and EBER are expressed in type-1 latency. Type-2 latency includes LMP1, 2A, and 2B whereas in type 3 latency, all EBNAs and LMPs are expressed.16

EBNA2 is required for the B-cell–transforming ability of the virus.17,18 Indeed, strains lacking EBNA2 cannot transform normal B lymphocytes into characteristic proliferating lymphoblasts.18 A 497 amino acid–long nuclear protein, EBNA2, is a transcription activator and regulator of both the viral and cellular genes. It does so not by direct DNA binding but through adapter proteins such as RBP-Jk/CBF1.19,20 Notably, c-MYC is positively regulated by this viral protein.21

miRNAs are noncoding RNAs, 20 to 22 nucleotides in length. They are evolutionarily conserved and have emerged as powerful regulators of gene expression.22 Based on their expression in cancer, they are either defined as onco-miRNAs or suppressor miRNAs.22 To avoid immune attack and establish latency, EBV expresses a battery of viral miRNAs and alters expression of many host miRNAs.23 Indeed, EBV compromises virus-specific surveillance and influences programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) through its own miRNAs.24-26 In the tumor context, the viral latent growth transformation–associated proteins bring profound changes in cellular miRNAs by upregulating, among others, oncogenic miRNA-21 (miR-21), miR-155, and miR-17-92.27-30

Maintenance of immune self-tolerance is critically controlled by immune checkpoint (IC) proteins.31 Both costimulatory and coinhibitory signals play an important role in the regulation of T-cell responses. The inducible costimulator (ICOS)/inducible costimulator ligand (ICOSL) interaction on T cells and the antigen-presenting cells, respectively, is an example of the former, and PD/PDL1 engagement is an example of the latter. Among numerous strategies usurped by tumor cells to avoid immune recognition, one of the most noted strategies includes high expression of PD-L1.32,33 In contrast, a compromised ICOS/ICOSL interaction as a mechanism of immune evasion has, to our knowledge, not been investigated in EBV-associated B-cell neoplasms.

Both in asymptomatic latent infection in healthy individuals and in the virus-associated cancers, EBV uses several strategies to become immunologically invisible.34,35 These include mutation of its immunogenic epitopes36 and downregulation of HLA class I expression.35,37 Recently, we have shown that EBNA2 upregulates PD-L1 by downregulating miR-34a.38 In the present study, we asked whether EBNA2 regulates the costimulatory molecule ICOSL, how this affects tumor immunogenicity and cell proliferation, and whether miRNAs are involved in this.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

A total of 14 cell lines were used in this study and are described in the supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website.27,38-45 U2932, an EBV-negative BCL6+ DLBCL cell line,39 and its EBV-infected and EBNA2-transfected counterparts have previously been described in detail by us elsewhere.27,38,40 Further details are provided in supplemental Material and methods.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were extracted from 3 million cells lysed in radio-immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer. Protein lysates (30 μg) were electrophoresed on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes at a constant amperage of 400 mA for 1.5 hours in transfer buffer. Further details can be found in supplemental Material and methods.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from cell lines was isolated using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Plus kit (Zymo Research) according to the vending company’s instructions. The integrity of RNA was routinely checked using 1% agarose gel. RNA (40 ng) was reverse transcribed from each sample. The complementary DNA synthesis from mature miR-24 was performed with a TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, ThermoFisher Scientific). Further PCR details are in supplemental Material and methods.

Flow cytometry analysis

The expression of ICOSL was assessed by flow cytometry using a monoclonal antibody (eBioscience Inc, San Diego, CA) with its matched isotype control. Fixable viability dye was also included in the analysis to exclude dead cells. A total of 50 000 live cells were analyzed per sample. The data analysis was performed by FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc, Ashland, OR). More details can be found in supplemental Material and methods.

Anti–miR-24 inhibitor transfection

The U2932 mycophenolic acid (MPA) vector or EBNA2-expressing cells were transfected with 40 nM of either miR-24 inhibitors or control inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells (1.5 × 106 per mL) were seeded in a 6-well plate at ∼70% confluence in a total volume of 2 mL and immediately transfected using DharmaFECT Duo transfection reagent (GE Dharmacon). After 48 hours, the cells were harvested for total RNA and protein extraction and flow cytometry.

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)

The ddPCR was performed using the Bio-Rad QX200 System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplification was carried out using 1 μL of complementary DNA template and 1 μL TaqMan probe of U6 or hsa-miR-24-3p (Applied Biosystems, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and ddPCR supermix for probe (no deoxyuridine triphosphate; Bio-Rad Laboratories). More details are in supplemental Material and methods.

Apoptosis assay

The MPA vector control and EBNA2-expressing U2932 cells were transfected with miR-24 inhibitors and controls. The cells were harvested 48 hours after transfection and washed in phosphate-buffered saline. Subsequently, 1 × 105 cells were assayed for apoptosis using the Phycoerythrin Annexin V Apoptosis Detection with 7-amino-actinomycin kit (BD Pharmingen). Further details can be found in the supplemental Material and methods.

Lentiviral transduction of ICOSL 3′ untranslated region (UTR)

The MISSION 3′ UTR Lenti GoClone of ICOSL (Switchgear Genomics, Sigma-Aldrich) or the corresponding control were transduced into 6 × 105 U2932 MPA vector control and U2932 EBNA2 cells in the presence of 8 μg/mL of polybrene. After 48 hours, the cells were selected in medium containing 0.2 μg/mL puromycin. Twelve days after selection, the cells were transfected with either miR-24 inhibitor or the control inhibitor using DharmaFECT Duo reagent. The luciferase activity was assessed with GloMax Explorer Multimode Microplate Reader (Promega).

Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)

Blood from 3 healthy donors was used to separate peripheral blood mononuclear cells, using Ficoll-Paque separation media (GE Healthcare). MLR was essentially performed as previously described.38 Further details are in the supplemental Material and methods. After 48 hours, all samples were treated for 5 hours with Golgi plug protein transport inhibitor, brefeldin (BD Biosciences) to inhibit cytokine accumulation in the Golgi complex and processed to measure interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemistry in biopsies from patients with DLBCL

All biopsies were obtained for diagnosis purposes after written consent from all patients and in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and conformed to Sapienza University ethical committee protocols. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded 3-μm sequential sections were cut for immunohistochemical staining, which was performed using automated platforms (Bond III, Leica Biosystems, Muttenz, Switzerland, and Ventana Benchmark Ultra, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Further details are available in supplemental Material and methods.

Results

ICOSL expression is high in EBNA2-lacking BL and DLBCL cell lines

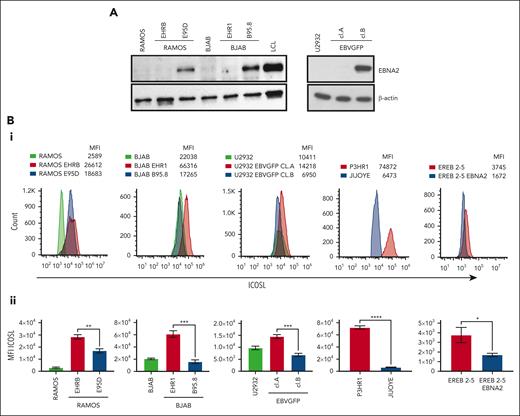

Ramos and BJAB cells infected with EBNA2-positive B95-8 (B converted) and EBNA2-negative P3HR1 (P converted) strains of EBV have been characterized previously.41,46 The B-converted Ramos E95D cells were EBNA2 positive and the P-converted Ramos EHRB cells were EBNA2 negative (Figure 1A, left panel). A similar EBNA2 expression profile is shown in BJAB cells infected with the 2 EBV strains (Figure 1A, left panel). As previously described, U2932 EBVGFP cell line (cl.)A was EBNA2 negative, whereas cl.B was EBNA2 positive (Figure 1A, right panel).40 Densitometry analysis is shown in supplemental Figure 1A. Next, we investigated ICOSL expression by flow cytometry (Figure 1Bi). The Ramos E95D, had higher ICOSL than the parental line, and Ramos EHRB-lacking EBNA2 showed even higher ICOSL expression. The BJAB B-converted cells did not show any significant difference in ICOSL when compared with the parental cells. Interestingly, the BJAB EHR1, showed a remarkable increase in ICOSL (Figure 1Bi). Similar results were obtained with U2932 EBV-infected cell lines. We analyzed ICOSL expression in the P3HR1 cell line carrying an EBNA2-deleted viral genome and its EBNA2-expressing parental cell line Jijoye. Indeed, EBNA2-lacking P3HR1 showed a notable increase in ICOSL. Finally, ICOSL expression was verified in EREB2-5 cells (a kind gift from Bettina Kempkes, Munich, Germany), which expresses estradiol-inducible EBNA2 in conjunction with the P3HR1 genome.44 In the presence of estradiol and thus EBNA2, ICOSL was reduced. Figure 1Bii shows average mean fluorescence intensity of ICOSL from 3 experiments. Combined, these data suggest that in the presence of the genomic EBNA2, ICOSL is reduced both in BLs and DLBCL.

EBNA2 and ICOSL expression in B-lymphoma cell lines infected with EBV. (A) Immunoblots show EBNA2 expression in parental, B95.8, and P3HR1 virus–converted RAMOS (E95D and EHRB RAMOS, respectively) cells and BJAB, BJAB-B95.8, and BJAB-EHR1 cells. EBNA2 expression in U2932 DLBCL cell line infected with the recombinant EBVGFP viral strain is also shown. U2932 EBVGFP cl.A is negative for EBNA2, whereas U2932 EBVGFP cl.B is positive. Total cell lysates were electrophoresed, and EBNA2 expression was verified by using anti-EBNA2 (PE2) monoclonal antibodies. The housekeeping protein, β-actin, was used as loading control. Densitometry analysis of immunoblots is shown in supplemental Figure 1A. (Bi) ICOSL expression in B and P virus–converted B-lymphoma cell lines, P3HR1 and Jijoye pair, and EREB2-5–carrying inducible EBNA2. Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) was measured by flow cytometer, CytoFLEX. One of 3 representative experiments is shown. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated ICOSL antibodies were used for the experiments. (Bii) Histograms show the average ICOSL MFI of 3 experiments. The significance of ICOSL MFI between EBNA2− vs EBNA2+ cell lines was calculated using 2-tailed unpaired t test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

EBNA2 and ICOSL expression in B-lymphoma cell lines infected with EBV. (A) Immunoblots show EBNA2 expression in parental, B95.8, and P3HR1 virus–converted RAMOS (E95D and EHRB RAMOS, respectively) cells and BJAB, BJAB-B95.8, and BJAB-EHR1 cells. EBNA2 expression in U2932 DLBCL cell line infected with the recombinant EBVGFP viral strain is also shown. U2932 EBVGFP cl.A is negative for EBNA2, whereas U2932 EBVGFP cl.B is positive. Total cell lysates were electrophoresed, and EBNA2 expression was verified by using anti-EBNA2 (PE2) monoclonal antibodies. The housekeeping protein, β-actin, was used as loading control. Densitometry analysis of immunoblots is shown in supplemental Figure 1A. (Bi) ICOSL expression in B and P virus–converted B-lymphoma cell lines, P3HR1 and Jijoye pair, and EREB2-5–carrying inducible EBNA2. Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) was measured by flow cytometer, CytoFLEX. One of 3 representative experiments is shown. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated ICOSL antibodies were used for the experiments. (Bii) Histograms show the average ICOSL MFI of 3 experiments. The significance of ICOSL MFI between EBNA2− vs EBNA2+ cell lines was calculated using 2-tailed unpaired t test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

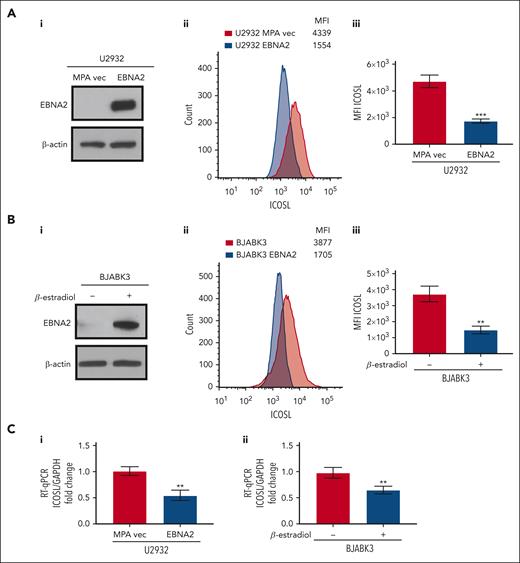

EBNA2-transfected B-cell lymphoma cells have lower ICOSL

To better understand whether EBNA2 expression alone is sufficient to negatively regulate ICOSL, we used EBNA2-transfected U2932 and BJAB cells. The EBNA2 transfectants of U2932 and estradiol-inducible BJABK3 cells have been described in detail elsewhere.38,44 EBNA2 expression in both cell lines is shown in Figure 2Ai,Bi. As seen in Figure 2Aii and Bii, the EBNA2-expressing U2932 and BJABK3 cells show a significant reduction in ICOSL. The mean ICOSL expression of 3 independent experiments is shown in Figure 2Aiii and Biii. In both these cell lines, EBNA2 expression also led to reduction in messenger RNA (mRNA) of ICOSL as shown in Figure 2Ci-ii. Taken together, these data show that EBNA2 alone is sufficient to reduce ICOSL in B-lymphoma cells.

Decreased ICOSL expression in EBNA2-transfected B-cell lymphomas. (Ai) Immunoblots showing EBNA2 expression in vector or EBNA2-transfected U2932 DLBCL. β-actin was used as a protein loading control. Densitometry analysis is shown in supplemental Figure 1B. (Aii) ICOSL MFI was assessed by flow cytometry. One representative experiment of 3 experiments showing a decrease in ICOSL in EBNA2-transfected U2932 cells. (Aiii) Histograms showing the average ICOSL MFI of 3 independent experiments by flow cytometry. (Bi) Immunoblots showing EBNA2 expression in the BJABK3 cell line transfected with a β-estradiol–inducible EBNA2 vector. β-actin was used as loading control. Densitometry analysis is shown in supplemental Figure 1B. (Bii) ICOSL MFI in BJAB and BJABK3 cells was assessed by flow cytometry. The analysis was performed with the FlowJo 10.8.2 portal. One representative experiment of 3 experiments is shown. (Biii) Average ICOSL MFI of 3 experiments by flow cytometry. (Ci-ii) ICOSL mRNA as measured by RT-qPCR in EBNA2-transfected B-lymphoma cell lines. The experiments were repeated at least 3 times and in triplicates each time. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as housekeeping gene to normalize the fold change of ICOSL. The fold change was calculated with the formula 2−ΔΔct. The statistical analysis was performed using a 2-tailed unpaired t test; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

Decreased ICOSL expression in EBNA2-transfected B-cell lymphomas. (Ai) Immunoblots showing EBNA2 expression in vector or EBNA2-transfected U2932 DLBCL. β-actin was used as a protein loading control. Densitometry analysis is shown in supplemental Figure 1B. (Aii) ICOSL MFI was assessed by flow cytometry. One representative experiment of 3 experiments showing a decrease in ICOSL in EBNA2-transfected U2932 cells. (Aiii) Histograms showing the average ICOSL MFI of 3 independent experiments by flow cytometry. (Bi) Immunoblots showing EBNA2 expression in the BJABK3 cell line transfected with a β-estradiol–inducible EBNA2 vector. β-actin was used as loading control. Densitometry analysis is shown in supplemental Figure 1B. (Bii) ICOSL MFI in BJAB and BJABK3 cells was assessed by flow cytometry. The analysis was performed with the FlowJo 10.8.2 portal. One representative experiment of 3 experiments is shown. (Biii) Average ICOSL MFI of 3 experiments by flow cytometry. (Ci-ii) ICOSL mRNA as measured by RT-qPCR in EBNA2-transfected B-lymphoma cell lines. The experiments were repeated at least 3 times and in triplicates each time. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as housekeeping gene to normalize the fold change of ICOSL. The fold change was calculated with the formula 2−ΔΔct. The statistical analysis was performed using a 2-tailed unpaired t test; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

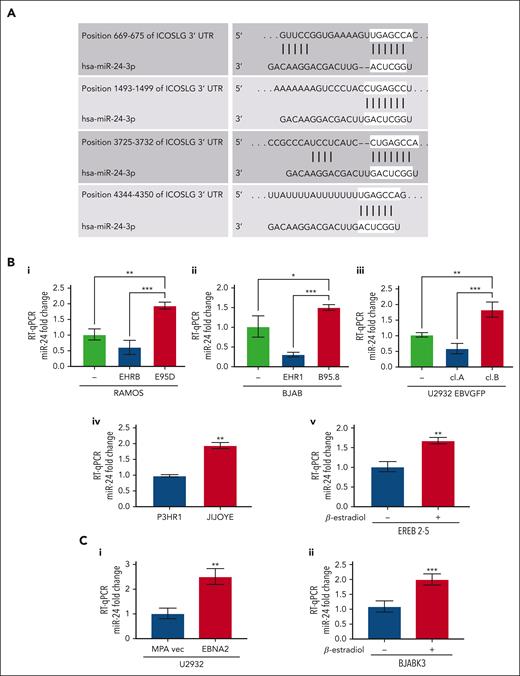

EBNA2 increases miR-24 expression in the virus-infected and transfected cells

Several previous observations including ours led us to focus on miR-24.27,47 TargetScan and miRWalk identified ICOSL as a potential target of miR-24 (also known as miR-24-3p; Figure 3A).48,49 The context score and strength of prediction of miR-24–ICOSL interaction is detailed in supplemental Material and methods. As seen in Figure 3Bi-iii, the in vitro infected EBNA2-positive BL and DLBCL cells have higher miR-24 expression. The P-converted Ramos and BJAB cells, and EBNA2-lacking U2932 EBVGFP cl.A cells had low miR-24 expression. Likewise, EBNA2-deleted P3HR1 BL cells had lower miR-24 expression than its isogenic EBNA2-positive parental Jijoye cell line (Figure 3Biv). Next, we tested whether EBNA2 induces miR-24 in an inducible setting. Indeed, EREB2-5 in the presence of estradiol, and thus of EBNA2, shows higher expression of miR-24 (Figure 3Bv). Finally, we verified that EBNA2 expression alone was sufficient to induce miR-24 in U2932 EBNA2 and BJABK3 transfectants. As shown in Figure 3Ci-ii, the EBNA2 expressors of both these cell lines have higher miR-24 than controls. We also verified pre–miR-24 expression in EBNA2-transfected U2932 and BJABK3 cells (supplemental Figure 2). The expression of pre–miR-24 transcript was lower in both cell lines in the presence of EBNA2. Reduced pre-miR levels and an increase in the corresponding mature miRNA due to increased RNA processing have been frequently observed.50,51

miR-24 expression increases in EBV-infected and EBNA2-transfected B-cell lymphoma cell lines. (A) TargetScanHuman 7.0 algorithm predicted 4 consequential miR-24 seed sequence pairing in the 3′ UTR of ICOSL mRNA. (B) miR-24 expression was evaluated by RT-qPCR in (Bi-ii) B- and P-converted RAMOS and BJAB cells; (Biii) EBNA2-negative U2932 EBVGFP cl.A and EBNA2-positive cl.B; (Biv) in EBNA2-negative P3HR1 and its isogenic EBNA2-positive JIJOYE cells; (Bv) in EREB2-5–containing estradiol-inducible EBNA2. Statistical significance of the differences was estimated through Dunnett multiple comparison in ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. (Ci-ii) miR-24 expression in EBNA2-transfected B-lymphoma cell lines. RT-qPCR was performed to assess the fold change of miR-24 levels in (Ci) U2932 EBNA2-transfected vs vector alone cell line and (Cii) in BJABK3 in which EBNA2 was induced with β-estradiol and its corresponding parental cell line BJABK3. P values were calculated through 2-tailed unpaired t test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. The fold change of miR-24 was calculated with the formula 2−ΔΔct, relative to the housekeeping gene RNU6 in each sample.

miR-24 expression increases in EBV-infected and EBNA2-transfected B-cell lymphoma cell lines. (A) TargetScanHuman 7.0 algorithm predicted 4 consequential miR-24 seed sequence pairing in the 3′ UTR of ICOSL mRNA. (B) miR-24 expression was evaluated by RT-qPCR in (Bi-ii) B- and P-converted RAMOS and BJAB cells; (Biii) EBNA2-negative U2932 EBVGFP cl.A and EBNA2-positive cl.B; (Biv) in EBNA2-negative P3HR1 and its isogenic EBNA2-positive JIJOYE cells; (Bv) in EREB2-5–containing estradiol-inducible EBNA2. Statistical significance of the differences was estimated through Dunnett multiple comparison in ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. (Ci-ii) miR-24 expression in EBNA2-transfected B-lymphoma cell lines. RT-qPCR was performed to assess the fold change of miR-24 levels in (Ci) U2932 EBNA2-transfected vs vector alone cell line and (Cii) in BJABK3 in which EBNA2 was induced with β-estradiol and its corresponding parental cell line BJABK3. P values were calculated through 2-tailed unpaired t test; ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. The fold change of miR-24 was calculated with the formula 2−ΔΔct, relative to the housekeeping gene RNU6 in each sample.

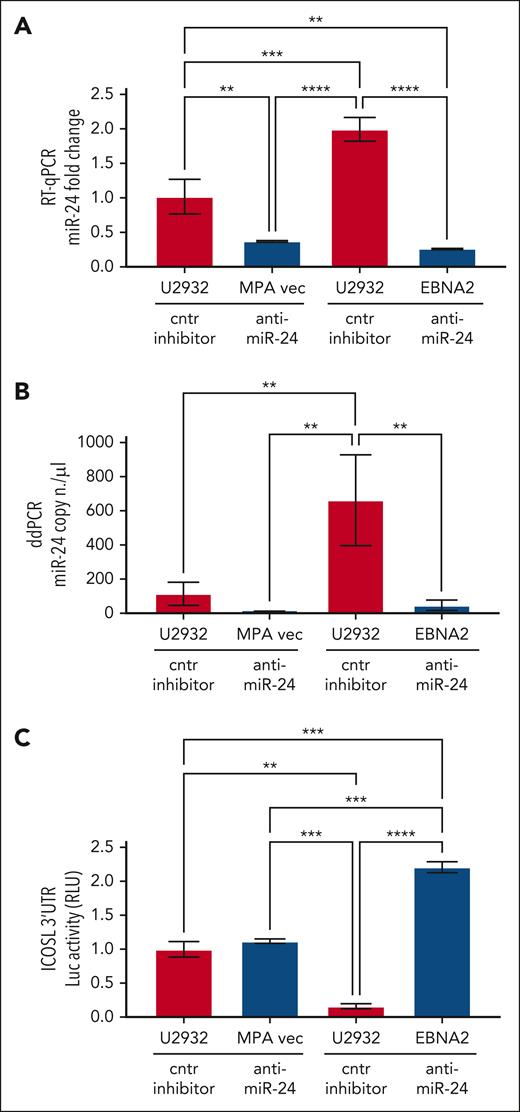

Validation of the ICOSL 3′ UTR as an miR-24 target in U2932 DLBCL

To study the role of miR-24 in the regulation of ICOSL, ICOSL 3′ UTR lentivirus–transduced U2932 EBNA2 cells and corresponding control cells were transfected with either anti–miR-24 or control inhibitor. Figure 4A shows expression of miR-24 by RT-qPCR. Indeed, anti–miR-24 transfected U2932 EBNA2 and vector control cells had significantly reduced miR-24 in comparison with the same cells transfected with a control inhibitor. To further verify the efficiency of reduction of miR-24, we performed ddPCR. Figure 4B shows a significant reduction in miR-24 copy numbers in U2932 EBNA2 cells transfected with miR-24 inhibitor. Next, luciferase activity was measured in U2932 EBNA2 and vector control cells. Figure 4C shows significantly higher ICOSL 3′ UTR luciferase activity after inhibition of miR-24 in U2932 EBNA2 cells, than in control cells. These data indicate that ICOSL is an authentic miR-24 target.

Inhibition of miR-24 in U2932 EBNA2-transfected cells induces ICOSL 3′ UTR luciferase activity. (A) Assessment of miR-24 levels by RT-qPCR in U2932 MPA vector and EBNA2 cells at 48 hours after control inhibitor and anti–miR-24 transfection. RNU6 housekeeping gene was used to normalize miR-24 fold change. (B) ddPCR shows the copy number of miR-24 per μL in each transfection. RNU6 housekeeping gene was used to normalize miR-24 copy number per μL in each sample. (C) Luciferase (Luc) assay was performed at 48 hours after transfection with control (cntr) inhibitors and anti–miR-24 in triplicates for each sample. Increased activity of ICOSL 3′ UTR is observed after inhibition of miR-24 in U2932 EBNA2 cells. Luc activity was measured as relative luminometer units (RLU) ratio between ICOSL 3′ UTR and the control 3′ UTR, to normalize RLU for each sample. The histogram demonstrates fold change in luc activity compared with U2932 MPA vector transfected with the cntr inhibitor. All experiments were repeated at least 3 times. One-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test was applied to evaluate statistical significance; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Inhibition of miR-24 in U2932 EBNA2-transfected cells induces ICOSL 3′ UTR luciferase activity. (A) Assessment of miR-24 levels by RT-qPCR in U2932 MPA vector and EBNA2 cells at 48 hours after control inhibitor and anti–miR-24 transfection. RNU6 housekeeping gene was used to normalize miR-24 fold change. (B) ddPCR shows the copy number of miR-24 per μL in each transfection. RNU6 housekeeping gene was used to normalize miR-24 copy number per μL in each sample. (C) Luciferase (Luc) assay was performed at 48 hours after transfection with control (cntr) inhibitors and anti–miR-24 in triplicates for each sample. Increased activity of ICOSL 3′ UTR is observed after inhibition of miR-24 in U2932 EBNA2 cells. Luc activity was measured as relative luminometer units (RLU) ratio between ICOSL 3′ UTR and the control 3′ UTR, to normalize RLU for each sample. The histogram demonstrates fold change in luc activity compared with U2932 MPA vector transfected with the cntr inhibitor. All experiments were repeated at least 3 times. One-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test was applied to evaluate statistical significance; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

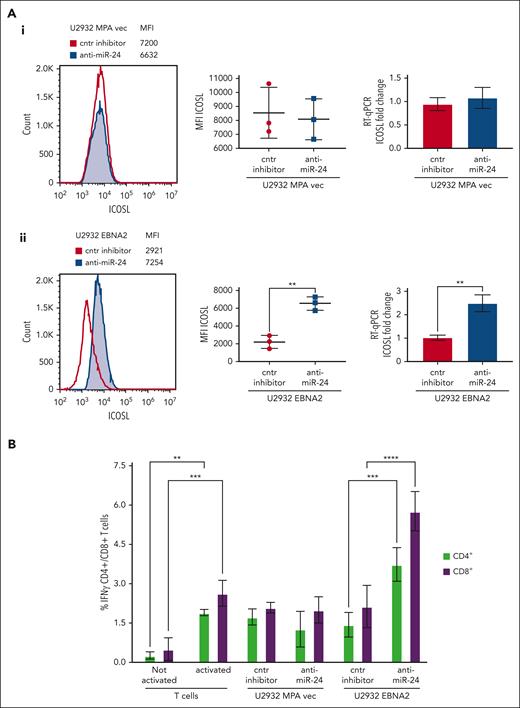

Inhibition of miR-24 leads to reconstitution of ICOSL expression and tumor immunogenicity in U2932 DLBCL

To assess the biological relevance of miR-24 inhibition, we analyzed ICOSL expression in vector transfected or U2932 EBNA2 cells after knockdown of miR-24 expression. Figure 5Aii (left) shows a significant increase of ICOSL expression in U2932 EBNA2 cells after miR-24 inhibition. Figure 5Aii (middle panel) shows an average ICOSL increase in 3 experiments, and the corresponding mRNA increase is shown in Figure 5Aii (right panel). In contrast, in U2932 MPA vector cells, the inhibition of miR-24 with anti–miR-24 inhibitor or control inhibitors did not affect ICOSL expression (Figure 5Ai), showing that this was EBNA2 dependent.

Inhibition of miR-24 reconstitutes ICOSL expression and restores tumor immunogenicity in a MLR assay. (A) ICOSL MFI after anti–miR-24 expression in (Ai) U2932 MPA vector transfected with control inhibitor and anti–miR-24. The middle panel shows ICOSL MFI in 3 independent flow cytometry experiments as whiskers. The right panel shows fold change in ICOSL mRNA expression by RT-qPCR after anti–miR-24 transfection. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene. (Aii) An increase in ICOSL after inhibition of miR-24 expression in U2932 EBNA2. Three independent experiments by flow cytometry show statistically significant increase of ICOSL (middle panel), also confirmed by mRNA RT-qPCR (right panel). P values were calculated through 2-tailed unpaired t test; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (B) MLR to evaluate T-cell activation as result of ICOSL reconstitution after miR-24 downregulation. T cells were activated for 72 hours in plates coated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies. Irradiated U2932 MPA vector and U2932 EBNA2 were cocultivated with activated T cells (effector). The effector-to-target ratio was 1:10. The target cells were transfected with control inhibitor or anti–miR-24 molecules before cocultivation with the effector cells. The coculture was carried out for 48 hours, and the cells were stained for CD4/CD8 and IFN-γ and processed for flow cytometry. All experiments were repeated at least 3 times and with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 3 healthy donors. Statistical analysis was performed with two-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Inhibition of miR-24 reconstitutes ICOSL expression and restores tumor immunogenicity in a MLR assay. (A) ICOSL MFI after anti–miR-24 expression in (Ai) U2932 MPA vector transfected with control inhibitor and anti–miR-24. The middle panel shows ICOSL MFI in 3 independent flow cytometry experiments as whiskers. The right panel shows fold change in ICOSL mRNA expression by RT-qPCR after anti–miR-24 transfection. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene. (Aii) An increase in ICOSL after inhibition of miR-24 expression in U2932 EBNA2. Three independent experiments by flow cytometry show statistically significant increase of ICOSL (middle panel), also confirmed by mRNA RT-qPCR (right panel). P values were calculated through 2-tailed unpaired t test; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (B) MLR to evaluate T-cell activation as result of ICOSL reconstitution after miR-24 downregulation. T cells were activated for 72 hours in plates coated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies. Irradiated U2932 MPA vector and U2932 EBNA2 were cocultivated with activated T cells (effector). The effector-to-target ratio was 1:10. The target cells were transfected with control inhibitor or anti–miR-24 molecules before cocultivation with the effector cells. The coculture was carried out for 48 hours, and the cells were stained for CD4/CD8 and IFN-γ and processed for flow cytometry. All experiments were repeated at least 3 times and with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 3 healthy donors. Statistical analysis was performed with two-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

MLR assays were used to understand the immunological significance of ICOSL reconstitution after miR-24 inhibition. The irradiated stimulator U2932 vector or U2932 EBNA2 and either their control or anti–miR-24-transfected derivatives were added in an MLR. Successful anti–miR-24 delivery was confirmed by RT-qPCR and ddPCR (Figure 4). The activated T-cell state was corroborated by increased IFN-γ production (Figure 5B). Importantly, U2932 EBNA2 boosted IFN-γ production by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, only when miR-24 was reduced with anti–miR-24 molecules (Figure 5B). These data suggest that EBNA2, by decreasing ICOSL through miR-24, reduces T-cell activation, and by inhibiting miR-24, tumor immunogenicity can be restored through reconstitution of ICOSL.

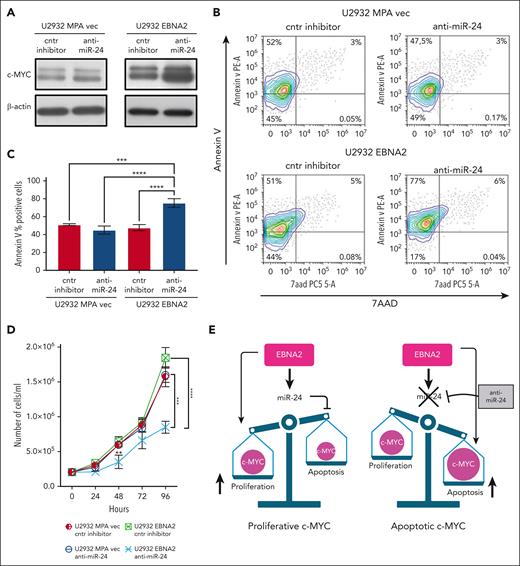

EBNA2 induces miR-24 to maintain proproliferative levels of c-MYC

We confirmed that EBNA2 increases c-MYC (Figure 6A, right panel). miR-24 is known to target c-MYC.52 Thus, it is intriguing that EBNA2 positively affects both c-MYC and its negative regulator, miR-24. To better understand this, we used anti–miR-24 molecules to downregulate this miRNA in U2932 EBNA2 cells. Inhibition of miR-24 expression further increased c-MYC expression (Figure 6A, right panel). Because high levels of MYC are known to induce apoptosis,53 we measured apoptosis in EBNA2-expressing cells after transfecting anti–miR-24 molecules. High c-MYC expression, as a result of downregulation of miR-24, increased apoptosis (Figure 6B, lower panel). Reduction of miR-24 in U2932 EBNA2 cells reduced BCL2 expression (supplemental Figure 3). Figure 6C shows the percentage increase in annexin V. Next, we tested whether inhibition of miR-24 in U2932 EBNA2 cells affected their proliferation rate. As shown in Figure 6D, U2932 EBNA2 cells transfected with miR-24 inhibitor grew significantly slower than controls, indicating that the reduction in miR-24 and consequent increase in apoptotic c-MYC reduces the cell proliferation rate. Overall, these data suggest that EBNA2 may increase miR-24 for fine-tuning and maintaining proproliferative levels of c-MYC (Figure 6E).

Inhibition of miR-24 increases c-MYC, induces apoptosis, and reduces cell proliferation in U2932 DLBCL. (A) Expression of c-MYC in U2932 MPA vector (left panel) and in U2932 EBNA2 (right panel). EBNA2 expression increases c-MYC in U2932, which is further increased upon inhibition of miR-24 (right panel). β-actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry of blots is shown in supplemental Figure 1C. (B) The percentage of apoptotic cells in U2932 MPA vector and EBNA2 cells transfected with control inhibitors and anti–miR-24 was performed by using PE annexin V staining with 7-amino-actinomycin (7-AAD) vital dye. The graphs represent annexin V and 7AAD density plots, showing a gradient increase of the cell distribution. Cells stained only with annexin V are in early apoptosis. (C) The histograms represent the percentage annexin V–positive cells from 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test. (D) Inhibition of miR-24 reduces cell proliferation. In total, 2 × 105 cells per mL were seeded and counted daily. Trypan blue exclusion assay was performed to estimate the number of cells per mL at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours, after transfecting U2932 vector or EBNA2 transfectants with control inhibitor or anti–miR-24. Statistical significance was calculated with ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test. At 48 hours, ∗∗P < .01, and at 96 hours, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (E) Schematic representation of miR-24 increase by EBNA2 for rheostatic maintenance of proproliferative c-MYC (left) and therapeutic potential of anti–miR-24 molecules (right).

Inhibition of miR-24 increases c-MYC, induces apoptosis, and reduces cell proliferation in U2932 DLBCL. (A) Expression of c-MYC in U2932 MPA vector (left panel) and in U2932 EBNA2 (right panel). EBNA2 expression increases c-MYC in U2932, which is further increased upon inhibition of miR-24 (right panel). β-actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry of blots is shown in supplemental Figure 1C. (B) The percentage of apoptotic cells in U2932 MPA vector and EBNA2 cells transfected with control inhibitors and anti–miR-24 was performed by using PE annexin V staining with 7-amino-actinomycin (7-AAD) vital dye. The graphs represent annexin V and 7AAD density plots, showing a gradient increase of the cell distribution. Cells stained only with annexin V are in early apoptosis. (C) The histograms represent the percentage annexin V–positive cells from 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test. (D) Inhibition of miR-24 reduces cell proliferation. In total, 2 × 105 cells per mL were seeded and counted daily. Trypan blue exclusion assay was performed to estimate the number of cells per mL at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours, after transfecting U2932 vector or EBNA2 transfectants with control inhibitor or anti–miR-24. Statistical significance was calculated with ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test. At 48 hours, ∗∗P < .01, and at 96 hours, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (E) Schematic representation of miR-24 increase by EBNA2 for rheostatic maintenance of proproliferative c-MYC (left) and therapeutic potential of anti–miR-24 molecules (right).

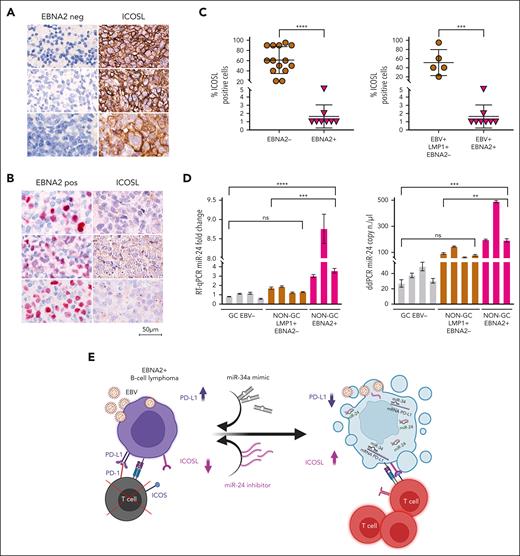

ICOSL is downregulated and miR-24 is upregulated in EBNA2-positive clinical DLBCL samples

To investigate the clinical relevance and consistency of the in vitro data, we selected 22 cases of DLBCL from 1113 cases in our archives, diagnosed between 2018 and 2023 (supplemental Figure 4). Diagnosis of DLBCLs was carried out according to the World Health Organization criteria.54 The cell of origin was evaluated according to Han classification.55 Clinical details of each case are reported in Table 1. ICOSL expression was evident in all EBER-negative GC and non-GC DLBCL, varying between 20% and 90%. Figure 7A shows strong ICOSL membrane staining in most neoplastic cells in 3 representative EBV-negative EBNA2-negative GC DLBCL cases. ICOSL expression in a few additional EBV-negative DLBCL biopsies is shown in supplemental Figure 5. In contrast, all EBNA2-positive DLBCLs showed downregulated ICOSL expression (Figure 7B; supplemental Figure 6). ICOSL in 1 reactive lymph node control is shown in supplemental Figure 7.

Clinical details of the cases included in the study

| Case ID∗ . | Diagnosis DLBCL . | Type . | Sex . | Age, y . | EBER . | EBNA2 %† . | ICOSL %† . | LMP1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IDD‡ | Non-GC | Male | 74 | + | 43 | <1 | + |

| 2 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 71 | + | 65 | <1 | + |

| 3 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 32 | + | 36 | <1 | + |

| 4 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 56 | + | 45 | <1 | + |

| 5 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 70 | + | 48 | <5 | + |

| 6 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 71 | + | 40 | <1 | + |

| 7 | IDD | Non-GC | Female | 52 | + | 65 | <1 | + |

| 8 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 83 | + | 70 | <1 | + |

| 9 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 58 | + | − | >95 | + |

| 10 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 59 | + | − | 20 | + |

| 11 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 48 | + | − | 40 | + |

| 12 | IDD | Non-GC | Female | 86 | + | − | 60 | + |

| 13 | IDD | Non-GC | Female | 72 | + | − | 40 | + |

| 14 | IDD | GC | Male | 64 | − | − | 90 | − |

| 15 | NOSˆ | GC | Male | 83 | − | − | 50 | − |

| 16 | NOS | Non-GC | Male | 73 | − | − | 60 | − |

| 17 | NOS | Non-GC | Female | 83 | − | − | >90 | − |

| 18 | NOS | Non-GC | Male | 97 | − | − | 50 | − |

| 19 | NOS | GC | Female | 49 | − | − | 60 | − |

| 20 | NOS | GC | Male | 48 | − | − | >90 | − |

| 21 | NOS | GC | Female | 88 | − | − | >90 | − |

| 22 | NOS | Non-GC | Female | 50 | − | − | 20 | − |

| 23 | CTRL | R LN | − | − | 20 | − | ||

| 24 | CTRL | R LN | − | − | 20 | − |

| Case ID∗ . | Diagnosis DLBCL . | Type . | Sex . | Age, y . | EBER . | EBNA2 %† . | ICOSL %† . | LMP1 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IDD‡ | Non-GC | Male | 74 | + | 43 | <1 | + |

| 2 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 71 | + | 65 | <1 | + |

| 3 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 32 | + | 36 | <1 | + |

| 4 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 56 | + | 45 | <1 | + |

| 5 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 70 | + | 48 | <5 | + |

| 6 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 71 | + | 40 | <1 | + |

| 7 | IDD | Non-GC | Female | 52 | + | 65 | <1 | + |

| 8 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 83 | + | 70 | <1 | + |

| 9 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 58 | + | − | >95 | + |

| 10 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 59 | + | − | 20 | + |

| 11 | IDD | Non-GC | Male | 48 | + | − | 40 | + |

| 12 | IDD | Non-GC | Female | 86 | + | − | 60 | + |

| 13 | IDD | Non-GC | Female | 72 | + | − | 40 | + |

| 14 | IDD | GC | Male | 64 | − | − | 90 | − |

| 15 | NOSˆ | GC | Male | 83 | − | − | 50 | − |

| 16 | NOS | Non-GC | Male | 73 | − | − | 60 | − |

| 17 | NOS | Non-GC | Female | 83 | − | − | >90 | − |

| 18 | NOS | Non-GC | Male | 97 | − | − | 50 | − |

| 19 | NOS | GC | Female | 49 | − | − | 60 | − |

| 20 | NOS | GC | Male | 48 | − | − | >90 | − |

| 21 | NOS | GC | Female | 88 | − | − | >90 | − |

| 22 | NOS | Non-GC | Female | 50 | − | − | 20 | − |

| 23 | CTRL | R LN | − | − | 20 | − | ||

| 24 | CTRL | R LN | − | − | 20 | − |

CTRL, control; IDD, immune deficiency/dysregulation; NOS, not otherwise specified; R LN, reactive lymph node.

A total of 22 cases of DLBCL from the Sapienza Rome and University of Siena Pathology Department archives. Five were GC types, and 17 were non-GC types, classified according to the Hans algorithm.

A total of 6 areas were manually counted, and in each area at least 100 cells were scored. The number in the table is the average percentage positive cells.

IDD per the World Health Organization lymphoma classification, fifth edition.

ICOSL and miR-24 expression in DLBCL clinical tissues. (A) Three EBV-negative non-GC DLBCLs immunohistochemically stained for EBNA2 and ICOSL are shown. Cell membrane ICOSL positivity is in brown. These samples are negative for EBNA2. (B) Three cases of EBNA2-positive non-GC DLBCL and corresponding ICOSL expression are shown. Nuclear EBNA2 is shown in red. ICOSL is negative. (C) Scattered dot plot analysis representing ICOSL-positive cells in each case. The stained tissue sections were digitalized at a ×40 original magnification using Ventana DP200 Scan Scope. The number of positive cells was determined by manually counting 6 different areas and at least 100 cells in each area. For statistical significance, a 2-tailed unpaired t test was used; ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) miR-24 expression and copy number in DLBCLs by RT-qPCR (left panel) and ddPCR (right panel). Statistical significance was calculated with two-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (E) miRNA-based immunotherapy of EBV-associated EBNA2-expressing B-cell lymphoma. A proposed model underscoring the use of PD-L1, targeting miR-34a mimics as suggested by our previous data38 in combination with anti–miR-24 molecules to reconstitute ICOSL as an RNA-based immunotherapeutic approach (created with BioRender.com). Panel E is reproduced from Blandino et al,56 licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

ICOSL and miR-24 expression in DLBCL clinical tissues. (A) Three EBV-negative non-GC DLBCLs immunohistochemically stained for EBNA2 and ICOSL are shown. Cell membrane ICOSL positivity is in brown. These samples are negative for EBNA2. (B) Three cases of EBNA2-positive non-GC DLBCL and corresponding ICOSL expression are shown. Nuclear EBNA2 is shown in red. ICOSL is negative. (C) Scattered dot plot analysis representing ICOSL-positive cells in each case. The stained tissue sections were digitalized at a ×40 original magnification using Ventana DP200 Scan Scope. The number of positive cells was determined by manually counting 6 different areas and at least 100 cells in each area. For statistical significance, a 2-tailed unpaired t test was used; ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) miR-24 expression and copy number in DLBCLs by RT-qPCR (left panel) and ddPCR (right panel). Statistical significance was calculated with two-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparisons test; ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (E) miRNA-based immunotherapy of EBV-associated EBNA2-expressing B-cell lymphoma. A proposed model underscoring the use of PD-L1, targeting miR-34a mimics as suggested by our previous data38 in combination with anti–miR-24 molecules to reconstitute ICOSL as an RNA-based immunotherapeutic approach (created with BioRender.com). Panel E is reproduced from Blandino et al,56 licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Because EBNA2 and LMP1 are coexpressed in type-3 latency, we asked whether the latter could have any role in ICOSL downregulation. To answer this, we tested LMP1-positive but EBNA2-negative (type-2 latency) DLBCL and HL cases for ICOSL expression. Four type-2 latency non-GC DLBCLs and 4 HL cases were high ICOSL expressors (supplemental Figures 8 and 9). ICOSL expression in 7 additional HL cases is shown in supplemental Table 3. These data suggest that in type-2 latency–expressing DLBCL clinical samples tested, the reduced ICOSL does not correlate with LMP1 but most likely with EBNA-2. Thus, as summarized in Figure 7C, all EBNA2-negative DLBCL samples examined did express ICOSL, and in contrast, EBNA2-positive clinical samples had negligible levels of ICOSL. In agreement with the in vitro data, EBNA2-positive clinical samples have higher miR-24 expression and copy number as indicated by RT-qPCR and ddPCR, respectively (Figure 7D). Taken together, these data underscore that EBNA2 alone may be sufficient to downregulate ICOSL in DLBCL through induction of miR-24.

Discussion

To establish latency in healthy individuals and contribute to pathogenesis of cancers under specific conditions, EBV must overcome immune responses. We have previously shown that EBNA2 upregulates PD-L1 by downregulating miR-34a in B-cell lymphoma.38 Very little information is available on expression of ICOSL in lymphomas. Particularly, it is not known whether and how EBV influences this costimulatory IC. Here, we report that ICOSL is downregulated by EBNA2 by virtue of upregulating miR-24. We also found that EBNA2 increases this miRNA to rheostatically maintain proproliferative levels of c-MYC. Hence, EBNA2 by positively regulating miR-24 seems to be simultaneously affecting tumor immunogenicity and increasing cell proliferation.

The immunostimulatory interaction between ICOS and ICOSL is considered of fundamental importance in generation and activation of different T-cell populations and their effector functions. Indeed, ICOS is expressed by activated CD4+/CD8+ T, regulatory T and T follicular helper cell populations. In the context of tumor cells, an increase in ICOS–ICOSL interaction may tip the balance in favor of T-effector cells being recruited in cancer tissue.57 In preclinical studies, it was observed that the ICOS/ICOSL pathway was required for optimal therapeutic effect of anti–CTLA-4 antibodies.58 When murine melanoma cells expressing ICOSL were used as vaccines, the anti–CTLA-4 treatment was both qualitatively and quantitatively potentiated, and converted an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment to an immunostimulatory one.59 That costimulatory molecules play a critical role in controlling EBV-infected cells is clear from 2 lines of evidence. First, individuals with genetically compromising mutations in these molecules often develop EBV-associated pathologies.60 In contrast, most EBV infections and indeed EBV-associated cancers occur in immunocompetent individuals. A corollary to this, therefore, is that for EBV, surmounting the immune onslaught and establishing latency is a challenging task in the face of a functioning immune system. Negatively affecting costimulatory molecules in such situations would ensure viral survival. Interestingly, it has been reported that among the EBNA2-affected genes, a costimulatory molecule CD86 is downregulated.61 Thus, the findings of this study add a novel viral strategy that facilitates tumor immune escape.

The onco-miRs such as miR-21, miR-155, and miR-17-92 are often upregulated in B-cell lymphomas.27,29,62,63 Deregulated expression of miR-24 has been noted in different cancers.64-67 In EBV-associated lymphomas having type-3 latency, an increased miR-24 expression was reported, but which EBV-encoded gene is responsible for its upregulation was not known.63 Here, we show that EBNA2 induces miR-24 and that ICOSL is its authentic target. The reduced pre–miR-24 and increased mature miR-24, most likely because of an increased turnover,51 seem to suggest involvement of RNA processing. Indeed, EBNA2 is known to associate with DDX5,68 a RNA helicase, which in turn is associated with Drosha/DGCR8, the principal microprocessor complex involved in miRNA processing within the nucleus.69,70 Further studies will be needed to better understand these interactions. Data from this study, taken together with the previously identified upregulation of miR-21 and reduction in miR-34a by EBNA2, place this viral protein as 1 of the central regulators of cell proliferation through perturbation of miRNA expression.

EBNA2 upregulates MYC; this has been shown previously,21,71 and we confirm it here. However, how can we reconcile the data showing that EBNA2 increases not only MYC but also its negative regulator, miR-24? A previous study identified MYC as one of the targets of miR-24.52 A possible explanation for this paradox is provided by experiments related to miR-24 inhibition. When anti–miR-24 compounds were transfected into EBNA2–expressing U2932 DLBCL cells, the expression of MYC was even higher. These elevated MYC levels led to higher apoptosis. The proapoptotic functions of high MYC are well known.53,72,73 Based on these data, we suggest that EBNA2 induces miR-24 to maintain proproliferative levels of MYC and avoid MYC-driven apoptosis.

Acknowledging the limitation of the small cohort in this study, it is noteworthy, nonetheless, that all GC DLBCLs have higher expression of ICOSL (Table 1). In contrast, very low expression of ICOSL was frequently seen in EBNA2-positive DLBCLs. In view of the fact that non-GC DLBCLs have poorer prognosis,74 ICOSL expression could be taken into consideration as a predictive biomarker. The poor prognosis of non-GC DLBCLs and, particularly, of EBNA2-positive cases could be correlated with immune dysregulation. Indeed, patients with EBNA2-positive DLBCL in our cohort belonged to such a category. A critical question that begs discussion and to which perhaps there is no straightforward answer, is whether EBNA2 is the cause or the consequence of immunosuppression. Undoubtedly, in patients with immunosuppression caused either by HIV or iatrogenic immunosuppression as in patients who have received transplantation, EBV/EBNA2 may enter as a subsequent event to worsen immunosuppression. Interestingly, it has been reported that homozygous loss of ICOSL in 1 patient led to combined immunodeficiency characterized by defects in T-cell–dependent antibody and memory B-cell generation.75 It is thus conceivable that ICOSL compromised by viral factors could be an important immune evasion strategy in an otherwise immunocompetent host. Based on our data, we suggest that in non-AIDS and nontransplant DLBCLs without any apparent immunodeficiency,76,77 EBV through EBNA2 could play a prominent role in immunocompetence decline and consequent immune evasion.

It is known that the success rate with IC-blocking antibodies alone, although encouraging, is far from satisfactory.33 The data from murine models showing that efficacies of therapies based on anti–CTLA-4 are enhanced through the ICOS/ICOSL pathway, underscoring its critical contribution in improving cancer immunotherapy.33,59,78,79 Clinical trials with agonistic antibodies to ICOS are ongoing.80 The latest data from 1 such trial, however, suggest that the use of vopratelimab (an ICOS agonist antibody) as artificial ligand in combination with anti–PD-1 nivolumab showed only a modest objective response rate in solid cancers.81,82 Although more data from other clinical trials are awaited, we suggest that the reconstitution of natural ligand (ie, ICOSL) on tumor cells may prove to be a better alternative for combination therapy. It is in this context that we envisage an important role for anti–miR-24 molecules to reestablish ICOSL expression on tumor cells, which, in turn, may deliver more potent and qualitatively different signals to T cells than what has been observed thus far with agonistic antibodies to ICOS.

In summary, these data, together with our previous findings that show that EBNA2 increases PD-L1 by downregulating miR-34a, underscore the central role played by this viral protein in tampering with tumor immunogenicity.38 Considering that it is associated with drug resistance and that patients with EBNA2-positive DLBCLs have a poor overall survival,11,13 we suggest that this particular group of patients might benefit the most from IC-blocking therapy. Combined, these data highlight how miRNA-based therapeutic approaches involving reconstitution of miR-34a with mimics and downregulation of miR-24 by anti–miR-24 molecules (Figure 7E) could overcome the compound immunosuppression caused by high PD-L1 and low ICOSL expression in EBNA2-expressing B-cell lymphomas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gabriel Macinanti for technical help. Bettina Kempkes and Maria Masucci are gratefully acknowledged for providing cell lines. The authors also thank Mary Anna Venneri for providing access to the fluorescence-activated cell sorting facility.

This work was sponsored by Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale 2022 grants from the Italian Ministry of University and Research and Lega Italiana per la Lotta Contro i Tumori, Italy (P.T.), and the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (R35 CA232105, to F.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.L., C.G., F.S., P.T., and E.A. designed the research; M.L., L.M., E.M., F.C., S.L., and E.A. performed the research; S.L., L.L., and C.G. provided clinical and research samples; A.A. and C.M. analyzed data; and M.L., L.M., C.G., F.S., P.T., and E.A. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Pankaj Trivedi, Department of Experimental Medicine, Sapienza University, Viale Regina Elena 324, 00161 Rome, Italy; email: pankaj.trivedi@uniroma1.it; and Eleni Anastasiadou, Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine, Sapienza University, Via di Grottarossa 1035, 00189 Rome, Italy; email: eleni.anastasiadou@uniroma1.it.

References

Author notes

∗M.L. and L.M. contributed equally to this work.

Data are available on request from the corresponding authors, Pankaj Trivedi (pankaj.trivedi@uniroma1.it), and Eleni Anastasiadou (eleni.anastasiadou@uniroma1.it).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal