Massive, submassive, right heart strain, heart failure…these words inject fear and terror into the hearts of parents upon hearing test results diagnosing and characterizing pulmonary embolism (PE) in their child or adolescent. In this issue of Blood, Bastas and colleagues1 address practical questions about life after pediatric PE related to how comfortably children are able to breath and how active they are able to be.

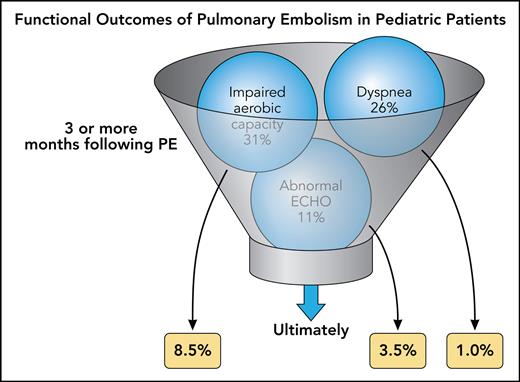

In a comprehensive long-term follow-up of 150 children and teens (<18 years, median age 16) with PE, the study showed a low rate of mortality (5%), recurrence (9%), and thrombus nonresolution (29%). Similarly, rates of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (0.7%), post-PE cardiac impairment (0.7%), and post-PE chronically abnormal echocardiograms (4%) were low. These data are comparable to numerous previous reports.2-10 The original contributions of this study from Bastas et al are the comprehensive post-PE exercise tolerance testing, stratification of outcomes in children by the presence or absence of underlying conditions, and determination of alternative explanations for abnormal findings. Two-thirds of the group without underlying conditions were female, of whom 70% were using oral contraceptives, while the group with underlying conditions (autoimmune, cancer, infections, cardiac disease and other) had more cases of hospital-acquired thrombosis and major thrombophilia. Overall, the study determined subjective dyspnea in about a quarter of children in follow-up ≥3 months following PE, with no difference related to the presence of underlying condition, but only 1% had persistent PE-related dyspnea when other potential causes were excluded (see figure). Similarly, ≥3 months after presentation with PE, 31% of the children had impaired aerobic capacity on exercise testing, again with no difference in underlying condition, in percent peak heart rate, peak workload in watts, peak oxygen saturation (SPO2), or exercise-induced desaturation. Ultimately only 8.5% of children had functional exercise impairment. Most children with long-term functional impairment were found to have decreased exercise performance based on deconditioning with the prevalence of deconditioning and impaired exercise tolerance, higher in children with major underlying medical conditions.

Functional outcomes of PE in pediatric patients. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Functional outcomes of PE in pediatric patients. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

PE has a high risk of dire outcomes in older adults with half of adults suffering post-PE syndrome with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, cardiac impairment, or functional impairment. The Bastas study on pediatric PE gives encouraging results that the outcome of PE in most pediatric patients is excellent, despite a high proportion of short-term abnormal test results, with a very low rate of long-term poor cardiopulmonary function or diminished aerobic capacity. This is likely due to the healthy heart and lungs of the pediatric patients prior to the episode of PE.

The article by Bastas et al has implications for immediate application to clinical practice. Despite frequent symptomatic and testing abnormalities at diagnosis and short-term follow-up, ultimately most of the abnormal outcomes were exercise intolerance related to deconditioning, often in the setting of severe underlying conditions that precluded active exercise. This article should inform pediatric practice to encourage return to aerobic sports and activities following PE as soon as physically feasible (usually starting gradually 4 weeks after presentation) in those who were previously able to participate, to focus enhanced outcome surveillance and intervention on children with preexisting conditions and to encourage children, adolescents and their parents that the outlook for future cardiopulmonary function and sports participation following PE is bright. Additionally, while this study is not the first to implicate oral contraceptives in adolescent female PE, it should resurrect a discussion of whether the use of progesterone only hormonal therapies in young teenaged girls is warranted to decrease this rare but potentially serious thrombotic complication.

Unanswered questions center around the best approaches for exercise rehabilitation in both previously well children and adolescents as well as those with significant debilitating medical conditions following an episode of PE. Also unknown are the long-term adult cardiopulmonary ramifications of pediatric PE. Finally, the psychosocial issues for parents allowing their children to return to strenuous sports and activities following a frightening intensive care unit stay for PE deserve to be explored. PE remains a serious condition that is increasing in pediatric patients, but the current study adds to our knowledge base guiding efforts to optimize functional outcomes.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal