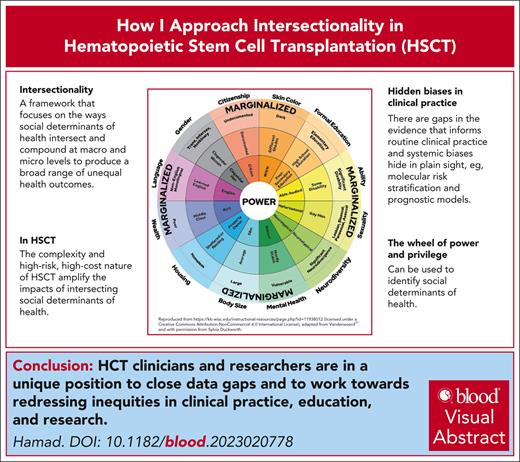

Visual Abstract

In the context of health care, intersectionality refers to a framework that focuses on the ways in which multiple axes of social inequality intersect and compound at the macro and micro levels to produce a broad range of unequal health outcomes. With the aid of tools such as the wheel of power and privilege, this framework can help identify systemic biases hidden in plain sight in the routine diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic paradigms used in clinical practice. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a high-cost, highly specialized complex procedure that exemplifies the impact of intersectional identities and systemic biases in health care systems, clinical research, and clinical practice. Examples include the derivation of clinical algorithms for prognosis and risk assessments from data with limited representation of diverse populations in our communities. Transplant clinicians and teams are uniquely positioned to appreciate the concept of intersectionality and to apply it in clinical practice to redress inequities in outcomes in patients with marginalizing social determinants of health. An intersectional approach is the most efficient way to deliver effective and compassionate care for all.

Background

According to the World Health Organization, social determinants of health (SDHs) can be more important than health care or lifestyle choices, accounting for 30% to 55% of health outcomes.1 These are the conditions under which people are born, grow, work, live, and age. These forces include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems.1 Equity in health care refers to the principle of ensuring that all individuals have equal access to health care services and opportunities and outcomes. Although equitable health care is an accepted goal, health care systems, including institutions, clinicians, researchers, and educators, are all challenged by it.2,3 A framework to scaffold an understanding of SDHs and support the advancement of this goal is vital for progress in this field. Modern Western medicine has evolved within a White, colonial, and patriarchal framework. This includes research, education, clinical practice, and public health policy. Individual clinicians are trained within this framework so that societal “othering” of minority groups in medicine reflects the social and cultural acceptance of this.4,5 Clinicians can be unaware of these biases and have limited training and education on how to mitigate them at individual and systemic levels.6

Intersectionality is well established in population health research, with the aim of understanding health care inequities with greater precision.7-9 The term “intersectionality” was coined by the American critical legal race scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989 and encapsulates ideas evolving historically within Black, Latina, feminist, queer, postcolonial, and indigenous (New Zealand Māori) activism and scholarly work that articulates the complex factors and processes that shape human lives.8,10 In health care, it refers to a framework that focuses on how multiple axes of social inequality intersect and compound at macro and micro levels within connected systems and structures of power (eg, law, politics, government, and media) that implicitly or explicitly promote interdependent forms of privilege and oppression to produce a broad range of unequal health outcomes.7,8 For example, a White woman from a lower socioeconomic group might be penalized for her gender and class when accessing health care and social services but has the relative advantage of race over a Black woman.7,8 These aspects inform one another and are not experienced separately.

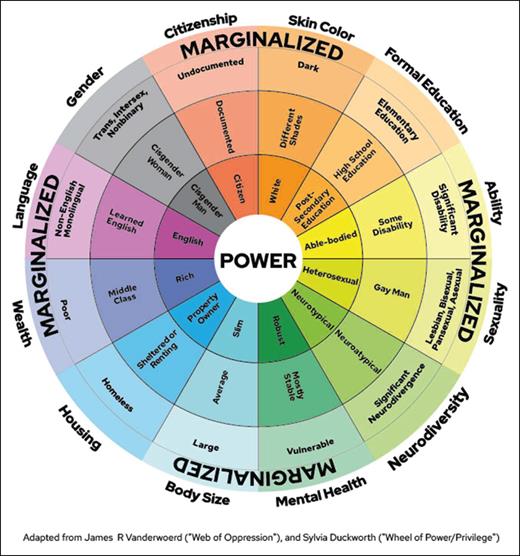

The wheel of power and privilege11,12 is a simplified illustrative way to reflect on the many intersecting identities and power structures with which we engage (Figure 1). This tool is not intended to capture all areas of marginalization but to provide examples and a framework to view power and privilege. Characteristics in the center reflect those who hold power and influence social structures and systems (not the majority). Those on the outside of the wheel reflect the characteristics associated with marginalization. Individuals with all the characteristics at the center are the most advantaged, whereas those who possess all the characteristics on the outside are the most disadvantaged. The categories represented in this wheel include body size, mental health, neurodiversity, sexuality, gender, ability, education, skin color, citizenship, language, wealth, and housing. It is not designed to be exhaustive but a way to consider potential characteristics that may be relevant in a local context. For example, it does not include age, indigenous status, religion, or culture, which should be included in certain clinical settings. This tool can aid clinicians and transplant teams in recognizing SDH risk factors that they may not have been aware of, and in proactively redressing what they can.

Wheel of power and privilege. Reproduced from https://kb.wisc.edu/instructional-resources/page.php?id=11938012 (licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License); adapted from Vanderwoerd11 and with permission from Sylvia Duckworth.

Wheel of power and privilege. Reproduced from https://kb.wisc.edu/instructional-resources/page.php?id=11938012 (licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License); adapted from Vanderwoerd11 and with permission from Sylvia Duckworth.

The concept of precision and risk-adapted medicine has focused on the molecular biology and genomics of diseases to develop diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic paradigms. This precision is subject to entrenched biases in the research. These biases intersect and can compound with the use of multiple biased sources of data to arrive at clinical algorithms. This is evident in the complex, high-cost, and highly specialized medicine exemplified by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT), in which historic and ongoing systemic biases can have compounding effects at every stage of the procedure. In recognition of inequities in access, efforts to mitigate these issues are being explored.13,14

Reviewing all relevant disparities in research and identifying all biases in HCT is beyond the scope of this article, but the following are examples of where acknowledgment of bias and data gaps is important for informed consent with balanced patient doctor discussions and decisions. The wheel of power and privilege11,12 was used to identify these in the literature. Some elements of the wheel have not been reported, such as the impact of religion, neurodiversity, gender, or sexuality on HCT outcomes. The following cases will be used to demonstrate potential biases in pretransplantation, peritransplantation, and posttransplantation care identified through the wheel of power and privilege.

Pretransplantation

Case 1: gender

A 22-year-old White woman was diagnosed with intermediate-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) based on an abnormal blood count to investigate fatigue and easy bruising. She underwent induction with 7 + 3 cytarabine, doxorubicin, and high-dose cytarabine consolidation. She achieved a complete hematologic response and underwent myeloablative allogeneic HCT (allo-HCT) with busulfan cyclophosphamide conditioning from a local male 10/10 matched unrelated donor (MUD) 3 months after induction. Her hospital stay was relatively uncomplicated, with only a short-lived neutropenic fever treated with appropriate antibiotics. She was discharged after 21 days to care for her parents whom she lived with. In the posttransplantation follow-up, she had mild chronic skin graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) that was well-managed with topical high-potency steroids and a slow immunosuppression taper. At an outpatient clinic 12 months after allo-HCT during screening for vaginal chronic GVHD and sexual function, she comments “I wish I could not have sex ever again.” Exploration of this comment reveals that she had been sexually abused by her father since the age of 10 years and that this abuse was ongoing during her treatment for AML and allo-HCT. Given the limitations of outpatient clinics, the focus of interaction shifted to immediate safety. Using a trauma-informed care approach, her consent was obtained for admission to allow for comprehensive physical and psychosocial assessments by a domestic violence specialist to facilitate interventions to ensure her safety.

Discussion

This case demonstrates a gender disadvantage or implicit bias. Pre-allo-HCT screening focuses on organ function and established diagnoses of mental health issues. In 2021, the World Health Organization reported that across their lifetime, 1 in 3 women was subjected to physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner or nonpartner, a statistic that has remained unchanged over the past decade.15 This patient had engaged with a broad range of health care professionals throughout her treatment; however, abuse went undetected despite many opportunities to screen for this prevalent issue in women’s lives. Routine psychosocial medical history does not specifically screen for sexual violence. However, this form of screening is considered routine in antenatal care because of heightened awareness of women’s health issues and should be part of pretransplantation screening.16

The lack of consideration of SDHs, including gender and population diversity in clinical trials on prognostic and therapeutic strategies, calls into question the broader applicability of data generated from these.17-20 This includes the treatment of diseases in which HCT is indicated based on risk models that use potentially biased genomic and outcome data. This is evidenced by ongoing racial disparities in the outcomes of hematological malignancies.17,21 The prime example discussed here is AML, but similar issues have been reported in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and other hematological malignancies.17,22,23 In the United States, Black patients have a shorter survival than White patients, with the disparity most pronounced in those aged <60 years, even after adjusting for socioeconomic, cytogenetic, and molecular risk factors. Although the Black race is an independent prognosticator of poor survival, the inclusion of Black patients in therapeutic clinical trials is limited.17,18 Another exacerbating bias is from the genomic studies used to develop molecular prognostication models that define AML risk, which have primarily been derived from White patients with AML.17,18 Bhatnagar et al demonstrated that Black patients harbored significantly fewer (good-risk) NPM1 mutations and more (poor-risk) IDH2 mutations compared with White patients with AML. In addition, although the overall survival of Black patients was adversely affected by IDH2 and FLT3-ITD mutations, NPM1, ASXL1, RUNX1, and TP53 mutations did not have the same prognostic relevance as in White patients.18 For example, the 3-year overall survival in Black patients with NPM1c/FLT3-ITDlow/no was 15% vs 60% in White patients.18 These findings not only call into question the applicability of current AML prognostic paradigms and, therefore, risk-adapted treatment options, including high-dose chemotherapy and patient selection for allo-HCT, but also novel agents in development based on these which will likely perpetuate bias and potentially misinformation.17,23

Peritransplantation

Case 2: gender/ethnicity/migration status/health care access/language

A 19-year-old woman had recently migrated from India to Australia (English is her second language) after marrying an Australian citizen. She presented with symptoms of fatigue and shortness of breath to a local general practitioner 2 weeks after arriving in the country. She was subsequently diagnosed with Philadelphia-positive ALL. Before the induction chemotherapy, the patient was offered free fertility preservation, which was unsuccessful. She was also diagnosed with active cardiac tuberculosis. She was informed that allo-HCT was at high risk because of her infection, that she was unlikely to find a donor due to her ethnicity, and that it would be difficult to access the procedure with her nonresident status. Under these pressures, her marriage suffered and her partner threatened her divorce and deportation. She struggled with the loss of fertility and the implications for her marriage.

With the support of her clinician and social worker, she received treatment as an inpatient to alleviate social and relationship pressures given that she was isolated with no family other than her husband. She received effective treatment for tuberculosis and achieved ALL remission. With advocacy, she received access to publicly funded treatment and was able to access imatinib maintenance therapy. She was referred for allo-HCT 6 months after diagnosis. She was identified as eligible for allo-HCT, and although there were concerns regarding donor availability due to ethnicity, an international male MUD was identified. She underwent a myeloablative cyclophosphamide total body irradiation transplant. She had an uncomplicated admission. She developed a mild itchy rash that was difficult to visualize but she had a subjective description of her skin appearing darker than usual. She was treated empirically with high-potency topical steroids, with resolution of her symptoms and no formal diagnosis of acute GVHD. Twelve months after allo-HCT, she was thought to have ongoing mild chronic skin GVHD that was responsive to topical high-potency steroids. She had experienced early menopause and sexual dysfunction. She had difficulty accessing free gynecological care from a clinician with expertise in post-allo-HCT complications. Through significant advocacy by her HCT physician, she accessed this after 3 months and started hormone replacement therapy and follow-up care. At 3 years follow-up, she was in remission and her chronic GVHD was asymptomatic. She was desperate for a child and explored egg donation in India, which was affordable, and unavailable in Australia. She was discouraged by her gynecologist because of “the unknown quality of health care in India.” She found this distressing and disclosed it to her HCT physician, who provided constructive advice and directly collaborated with her clinicians in India to assist. She returned to Australia after egg donation, assisted reproductive therapy in India, and delivered a healthy baby.

Discussion

This case demonstrates that numerous instances of vulnerability owing to multiple intersecting SDHs can be experienced throughout the course of care. It also demonstrates that although her ALL treatment team was attuned to her vulnerability to a coercive controlling partner, they considered her ethnicity and tuberculosis infection to be too high-risk for allo-HCT. The patient was in no position to ask questions, advocate for herself, or appreciate the risks of her disease, treatment, or other options. In these circumstances, it is important to recognize the potential for clinicians and teams to be overwhelmed by numerous socioeconomic issues and health-provider biases in referral patterns for HCT and overall care. The latter is exemplified in racial trauma in the advice she received from her gynecologist because she found the tone of the discourse distressing.

Potential referral bias has been demonstrated in the US literature, where Black patients are less likely to receive HCT,18,24 with racial disparities in outcomes being more prevalent in allo-HCT than in autologous HCT (auto-HCT).24 Attempts to estimate access to allo-HCT have traditionally relied on the analysis of surrogate estimates of SDHs against allo-HCT activity from large international registries.25-28 These studies had insufficient statistical power to detect differences in different populations, SDH characteristics, access barriers, and how they may interact.25-33

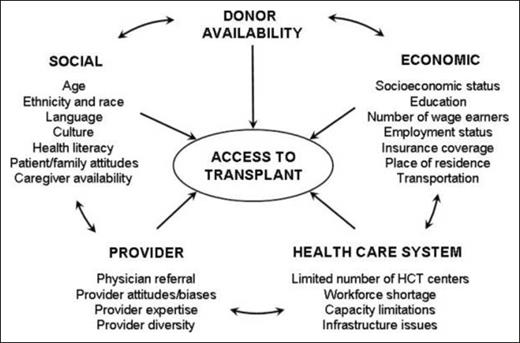

Allo-HCT presents a unique complexity because it relies on voluntary donor availability, where implicit or explicit biases also play a role.3,34 Minority ethnicities have a lower chance of finding a fully MUD.24,27,35,36 This is of particular importance in indigenous populations that are not represented in donor registries or countries with high ethnic diversity.37,38 Although the advent of posttransplantation cyclophosphamide expands the donor pool for these populations and therefore provides access to allo-HCT, it remains to be seen whether this translates to equity in outcomes.39 Minority groups are also likely to experience disparities in health from both donor and recipient perspectives.34 To address prior allo-HCT access paradigm deficiencies, Majhail et al established a framework that incorporates the potential barriers to allo-HCT access and includes some factors in the wheel of power and privilege, such as race, ethnicity, language, and literacy. Majhail et al also specifically includes age, carer availability, and family support40 (Figure 2). An important element of this model is the inclusion of provider bias and being the first model to acknowledge bias and systemic barriers due to health care resources and economic systems.24,27,35,40 Although this model is not exhaustive, it offers another framework that can account for the complexities of the allo-HCT process in conjunction with the wheel of power and privilege.41,42

Access to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant paradigm. Reproduced from Majhail et al,40 © 2010 American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, with permission from the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Access to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant paradigm. Reproduced from Majhail et al,40 © 2010 American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, with permission from the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Clinicians and service providers may hold the personal implicit biases that they need to consider as individuals. This is beyond the scope of this article, but consideration of one’s position on the wheel of power and privilege is the first step.6

However, there are more routinely applied biases that clinicians may not recognize. These can be gendered or racially adjusted measures of normal physiological ranges or prognostic algorithms based on biased assumptions.43,44 In HCT, organ function is used to assess complications and mortality risk. This includes simple investigations of kidney and lung function, which can lead to race-based adjustments. A tool more specific to HCT is the HCT comorbidity index (HCT-CI).45,46 The score was originally derived from a single US center of 1055 allo-HCT recipients, mostly male.45 The race or ethnicity of these patients has not been reported, but given the lack of diversity in HCT recipients in the United States, it is unlikely that these data were inclusive of diverse ethnic or racial groups. Although HCT-CI has been validated in other settings, these cohorts remain limited in their diversity.47-51 This is certainly the case in HCT recipients for nonmalignant diseases, where the most patients are White (69%).46 The potential biases that can be hidden in HCT-CI are the limited representation of the original cohort. Furthermore, there is a potential for bias in some comorbidity definitions that derive the score. The most problematic is obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2. It has recently been openly recognized that BMI is based on White European norms and is not predictive of health outcomes in different populations.52-55 The use of BMI in HCT-CI may overestimate the risk in some populations whereas underestimating it in others. There are risk factors for HCT-CI that are predicated on access to health care, such as psychiatric disturbance and peptic ulcer disease, and may be underestimated in those with SDHs. To a lesser extent, cerebrovascular disease may depend on health literacy or access to health care to obtain a formal diagnosis. The comorbidity of infection requiring antimicrobial treatment can be challenging to apply in international contexts with diverse endemic infectious disease landscapes that require prophylaxis through HCT.56 There is also diversity in the incidence of malignancy among different populations that are likely not represented in the HCT-CI development cohort.47-51,57 Overall, the reliability of the score in predicting outcomes in patients with diverse racial/ethnic/geographic backgrounds must be investigated before it can confidently be applied to all patients.49 Similarly, the disease risk index used in auto-HCT to prognosticate in clinical practice and stratify risk in clinical trials is based on data from 13 131 patients reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.58 Registry studies are challenged by the definition of race/ethnicity and lack of power to detect signals from diverse groups owing to the lack of diversity among HCT recipients.19 The data gaps contributing to these risk models need to be closed but at the very least considered by clinicians and researchers. The same applies to conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis data derived from the international clinical outcome registries.

Posttransplantation

Case 3: indigenous status/large body/rural geography/economic stress/sexuality

A 19-year-old man of Aboriginal descent from a rural town was transferred to a metropolitan hospital after presenting with shortness of breath and was diagnosed with a mediastinal mass on imaging. He was alone at the time of transfer, hospitalized for 2 weeks, and hospitalized for video-assisted thoracic surgery to biopsy the mass, which confirmed primary mediastinal lymphoma. He had a BMI of 36 kg/m2 and his DA-EPOCH-R dose was capped. Six months after the treatment, He struggled with travel and a lack of family support. His mother was a single parent and carer of 3 younger children who could not travel with him. He was supported by government funding for travel and social worker support facilitated access to free housing close to the hospital. He returned home but relapsed within 12 months and returned for salvage chemotherapy and auto-HCT, which interrupted his vocational training. He achieved a second remission, returned home, and gained employment as a part-time sales assistant at a local department store. He relapsed again within 12 months, received salvage therapy, and was scheduled for allo-HCT.

His indigenous ancestry was considered a major barrier to accessing a MUD, as the Australian donor registry is not enriched for this population and his BMI was also thought to be a risk factor. He did not have a matched sibling donor; however, a haploidentical-related donor was identified, and he underwent a myeloablative transplantation in the third remission. He had a surprisingly uncomplicated transplantation course, was monitored in free housing until 3 months after transplantation, and returned home. He was followed up at a rural fly-in/fly-out outreach hematology clinic by his HCT physician. During long-term follow-up, he struggled to secure and maintain employment. He disclosed that he is gay and that this has been a source of bullying in the workplace. He felt safe sharing his sexuality with his HCT physician but not with his family or friends. During the COVID-19 pandemic, travel to the rural clinic by physicians was not possible; therefore, care was delivered remotely by phone, as he had no access to the Internet or a computer for video conferencing. He developed chronic GVHD symptoms, with itchy eyes and itchy skin. He was advised to seek the assistance of a local general practitioner to examine him, but GVHD remained unrecognized. He developed shortness of breath and informed his HCT physician. The HCT physician held a case conference with his general practitioner. It became apparent that the general practitioner thought his red eyes were likely due to “cannabis use given the common practice in that town amongst young men of his background,” that he could not appreciate the skin being inflamed because of his “dark skin” and that he thought his weight loss was a “positive development” despite its unintentional nature. Lung function testing was not available close to home because of the cessation of this service during COVID-19. The HCT physician arranged a transfer to the HCT ward in the metropolitan hospital for inpatient diagnosis and management of severe chronic GVHD.

This young man felt that seeking medical assistance was futile in his hometown and that doing so threatened his tenuous employment, on which his family was dependent. During admission, a plan was implemented for weekly follow-up calls by the HCT team from either a nurse or his physician when he returned home. A government disability support application was created with the support of his HCT physician and social worker. A detailed letter to his general practitioner, with instructions to contact the HCT physician and center, was provided. He was given a letter to his employer to establish that he needed leniency on sick leave because of his health, and a direct line of communication with his HCT team was established. He was given a letter to present in any emergency (including legal or medical) to demonstrate that he had received an allo-HCT, was undergoing treatment, and that in case of any emergency, his HCT center needed to be contacted. A trauma-informed care approach was adopted to provide LGBTQ+ patient support and access to an Aboriginal Health Liaison officer. He was counseled regarding his nutrition with a Healthy at Every Size approach.59 Eventually, he was able to access financial support from the government. He was unemployed for 2 years and recently restarted part-time employment after better control of his steroid-refractory chronic GVHD with ruxolitinib.

Discussion

This case highlights the compounding negative impacts of numerous intersectional identities and SDHs. An issue specific to HCT is that many indigenous people are disconnected from their families owing to historic systematic relocation and displacement policies; therefore, sibling and haploidentical transplantation options can also be limited. The stress experienced by the patient due to isolation, generational and systemic racial trauma, sexuality-based trauma, and economic stress all likely had an impact on his recovery and the psychosocial impact of his disease and its treatment. Although his HCT team was not able to remedy broader systemic issues, they were able to put in more effort to support him by validating his experience, sourcing, and providing resources to assist him. Providing a safe space for patients to share negative experiences can be therapeutic.16,60 Clinicians and transplant teams need to be able to hear this with acceptance and validation and to avoid dismissal or denial of the realities that face those marginalized or minoritized in our society. As clinicians, we automatically have a position of power, and it can be difficult to understand what those without power might experience outside of our own frame of reference.

The evidence for post-HCT incidence of complications and treatment efficacy also suffers from a systemic bias. An example of this is acute GVHD, where there is a higher risk in terms of incidence and severity in less homogenous ethnicities, such as African Americans vs Scandinavian and Japanese populations.61-65 Even less is documented regarding the differences in the incidence, manifestations, and severity of chronic GVHD among different ethnic groups.66 Some studies have reported a higher incidence in Black patients, but this is difficult to interpret given the limited information on how GVHD manifests in different ethnicities. This is most recognizable because of the absence of images or definitions of skin manifestations in different ethnicities.67,68 Clinical trials for GVHD still have issues with inclusion of diverse patient populations. Landmark ruxolitinib studies in steroid-refractory acute and chronic GVHD had ∼70% White patients and 0% and 1.2% Black patients, respectively, in the treatment arm.69-71 Sex bias in GVHD research is also evident in the lack of trials on effective therapies for vaginal GVHD.72 Beyond GVHD, SDHs can emerge because of the impact of allo-HCT on quality of life, including financial stress, psychological and support system strain, and challenges in accessing survivorship care.73

Conclusion

It is important to recognize the gaps in the evidence that inform routine clinical practice, and the systemic biases that hide in plain sight. This can be challenging. The goal of delivering evidence-based high-quality care is one that all health care professionals and systems share. The most efficient way to achieve this is through an intersectional approach. Tools such as the wheel of power and privilege can help clinicians understand their position and potential blindness to realities and experiences that differ from their own. This tool also provides a framework that allows clinicians and researchers to identify and mitigate intersecting SDH risk factors in their patients and research design.

The complexity, high risk, and high cost of allo-HCT amplify the impact of intersecting SDHs, as demonstrated in the above cases. HCT clinicians and teams are well-equipped to manage many competing risks using various algorithms; therefore, integrating this into clinical practice is achievable. Awareness of these knowledge gaps in clinical assessments and conversations with patients is important for facilitating informed consent. Recognizing the impact of marginalization and related traumas can only be achieved by listening to those with lived experience and decentering our own experiences.16

HCT clinicians and researchers are in a unique position to question the current evidence and close data gaps, but also to redress the resulting inequities. Future HCT research based on registry data should integrate more SDH data sets and include diverse patient populations. Clinical trials need to be more inclusive of those most affected by the disease and those with the worst outcome disparities, and include data on SDHs. Diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic research that ultimately feeds into HCT research should clearly acknowledge the limitations of applicability to a broader population if diversity is not achievable. Researchers need to deliberately enrich their teams with members who have experience or interest in equity, diversity, and inclusion in research. We also need to codesign research integrating SDH data, specifically on SDHs in allo-HCT, with patients who are the most affected or vulnerable.

Ultimately each of us has an obligation to learn to be allies to our patients. This requires self-education, awareness, and deliberate practice. It is time to integrate intersectionality in all aspects of medicine so that we can deliver effective and compassionate care for all.

Authorship

Contribution: N.H. conceived and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.H. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Nada Hamad, Department of Haematology, St. Vincent's Hospital Sydney, 370 Victoria St, Darlinghurst, NSW 2042, Australia; email: nada.hamad@svha.org.au.

Comments

Intersectional impact of patient ancestry, socioeconomic status, gender, and parity on allograft access

Refs 1-4: Fingrut, Barker et al., Blood Adv., 2023a, 2023b, 2024a, & 2024b.