Key Points

RNA sequencing identified MEM- and GC-like FL subtypes associated with specific cell of origin, mutational profiles and clinical outcomes.

IHC can be used routinely to identify patients with MEM-like FL with adverse PFS who can benefit from treatments other than R-chemotherapy.

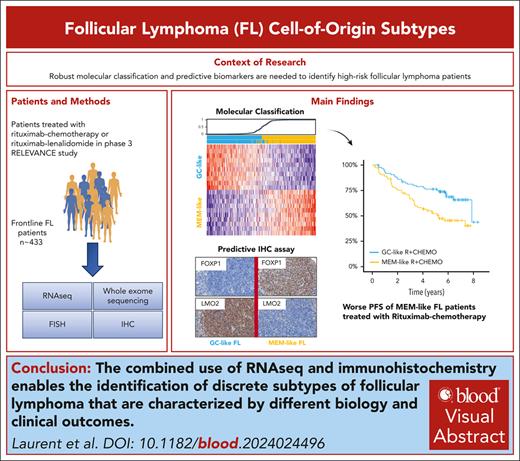

Visual Abstract

A robust prognostic and biological classification for newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma (FL) using molecular profiling remains challenging. FL tumors from patients treated in the RELEVANCE trial with rituximab-chemotherapy (R-chemo) or rituximab-lenalidomide (R2) were analyzed using RNA sequencing, DNA sequencing, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization. Unsupervised gene clustering identified 2 gene expression signatures (GSs) enriched in normal memory (MEM) B cells and germinal center (GC) B-cell signals, respectively. These 2 GSs were combined into a 20-gene predictor (FL20) to classify patients into MEM-like (n = 160) or GC-like (n = 164) subtypes, which also displayed different mutational profiles. In the R-chemo arm, patients with MEM-like FL had significantly shorter progression-free survival (PFS) than patients with GC-like FL (hazard ratio [HR], 2.13; P = .0023). In the R2 arm, both subtypes had comparable PFS, demonstrating that R2 has a benefit over R-chemo for patients with MEM-like FL (HR, 0.54; P = .011). The prognostic value of FL20 was validated in an independent FL cohort with R-chemo treatment (GSE119214 [n = 137]). An IHC algorithm (FLcm) that used FOXP1, LMO2, CD22, and MUM1 antibodies was developed with significant prognostic correlation with FL20. These data indicate that FL tumors can be classified into MEM-like and GC-like subtypes that are biologically distinct and clinically different in their risk profile. The FLcm assay can be used in routine clinical practice to identify patients with MEM-like FL who might benefit from therapies other than R-chemo, such as the R2 combination. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01476787 and #NCT01650701.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is a B-cell neoplasm characterized by an indolent clinical course with a median overall survival reaching 20 years with the current treatment modalities. However, FL is a heterogeneous disease in terms of its clinical behavior and its response to immunochemotherapy (IC), the first-line standard of care.1-4 Currently, the response to IC remains largely unpredictable with the available prognostic tools based on clinicobiological parameters, such as the FL-International Prognostic Index (FLIPI), FLIPI-2, and PRIMA-PI,1-4 or risk prediction models that combine high-risk clinical and genetic features,5 such as the m7-FLIPI.6 The impact of these tools on clinical management is limited. Therefore, there is compelling need for precision medicine that will enable better risk stratification at diagnosis and prospective selection of optimal upfront treatment.

The molecular cell-of-origin (COO) classification has enabled prognostic molecular categorization of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) into the favorable germinal center (GC) and unfavorable activated B-cell (ABC) subtypes7,8 and with genetic subgroups.9-11 Similar subcategorization has long been considered irrelevant in FL tumors, which seem to resemble normal GC light zone B cells.12 Still, preliminary studies pioneered a putative COO-based subtyping of FL tumors. In fact, epigenetic data suggested a distinction between germinal center B-cell (GCB) centrocyte-like and in vitro–activated plasmablast-like subtypes,13 whereas some BCL2-unrearranged FL tumors showed enrichment in ABC-like signatures14 or displayed microRNA profiles associated with a late GC phenotype.15

More recently, a set of 33 genes selected from GCB and ABC gene sets correlated with FL survival in a meta-analysis, but the influence of the treatment regimen was not assessed.16 In addition, a single-cell mass cytometry study revealed 2 recurrent FL patterns that resembled GC B cells and memory B cells,17 whereas genome sequencing identified 2 FL subgroups, including 1 with a mutational profile that resembled the GCB-DLBCL subtype.18 The 2 latter studies reported a correlation with the risk for histologic transformation, but not with survival.17,18 Overall, it seems that previous studies that suggested a COO-based prognostic model for FL require further characterization in a large cohort of first-line patients treated with IC or alternative therapy.

In this study, we analyzed samples from patients with advanced FL who were enrolled in the RELEVANCE study.19,20 When investigating the gene expression profiles, we defined 2 molecular FL subtypes, namely the MEM-like and GC-like subtypes, that had distinct biological characteristics and treatment-related outcomes. The worse outcome observed among patients with MEM-like FL who were treated with IC may be overcome with lenalidomide. Furthermore, we establish an immunohistochemistry (IHC) algorithm that enabled accurate classification of FL into those subtypes in routine practice.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

The phase 3 RELEVANCE trial19,20 (NCT01476787 and NCT01650701) compared the outcomes of treatment with rituximab-chemotherapy (R-chemo) or rituximab-lenalidomide (R2), followed by maintenance therapy with rituximab, among 1030 patients with FL presenting a high tumor burden, who were previously untreated.

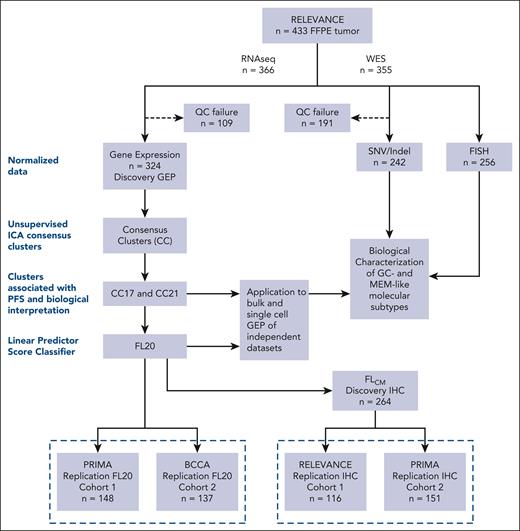

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsies that were obtained at the time of diagnosis from 433 patients were used to generate RNA sequencing (RNA-seq; n = 324; referred to as the discovery gene expression profiling [GEP] cohort), whole exome sequencing (WES) (n = 242), fluorescent in situ hybridization (n = 256), and IHC (n = 264) data (referred to as the discovery IHC cohort), as detailed in Figure 1 and the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website. To validate the data obtained in the discovery step, we used several replication cohorts. RNA expression data from the PRIMA21 study (n = 148 cases including 134 randomized patients, replication cohort 1) and the BCCA22 study (n = 137, replication cohort 2) were used to validate the prognostic significance of a gene expression classifier. Two additional replication cohorts containing FL samples were used to validate the IHC data. This included 116 cases from the RELEVANCE study (referred to as replication IHC cohort 1) and 151 cases from the PRIMA study (referred to as replication IHC cohort 2) (Figure 1).

Workflow and summary of cohorts used for RNA-seq, WES, and IHC. The study starts with a RELEVANCE biomarker cohort of 433 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples (top box). The subset of 324 RNA-seq analyzed RELEVANCE samples was considered as the discovery GEP cohort. The discovery steps and processes applied for clustering and development of an RNA-seq classifier are depicted (left dotted rectangle). In addition, WES and fluorescent in situ hybridization data could be analyzed in 242 and 256 FL tumors, respectively (right). To set up an IHC algorithm, a cohort of 264 FFPE samples with available RNA-seq data was used (discovery IHC cohort). Replication experiments (below dotted line) were performed for validation of the RNA-seq predictor (FL20) and IHC algorithm (FLcm) using different cohorts. Samples from the PRIMA trial were used for RNA-seq and IHC data validation (n = 148 and 151, respectively). Published data from BCCA (n = 137) were used for RNA-seq validation. Additional FFPE RELEVANCE samples without RNA-seq data (n = 116), which were not included in the initial discovery IHC cohort, were used to further validate IHC.

Workflow and summary of cohorts used for RNA-seq, WES, and IHC. The study starts with a RELEVANCE biomarker cohort of 433 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples (top box). The subset of 324 RNA-seq analyzed RELEVANCE samples was considered as the discovery GEP cohort. The discovery steps and processes applied for clustering and development of an RNA-seq classifier are depicted (left dotted rectangle). In addition, WES and fluorescent in situ hybridization data could be analyzed in 242 and 256 FL tumors, respectively (right). To set up an IHC algorithm, a cohort of 264 FFPE samples with available RNA-seq data was used (discovery IHC cohort). Replication experiments (below dotted line) were performed for validation of the RNA-seq predictor (FL20) and IHC algorithm (FLcm) using different cohorts. Samples from the PRIMA trial were used for RNA-seq and IHC data validation (n = 148 and 151, respectively). Published data from BCCA (n = 137) were used for RNA-seq validation. Additional FFPE RELEVANCE samples without RNA-seq data (n = 116), which were not included in the initial discovery IHC cohort, were used to further validate IHC.

IHC panel development

The correlations between RNA-seq and IHC profiles were explored using IHC on either whole sections or tissue micro-arrays (TMA) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsy samples in the 264 cases from the discovery IHC cohort, which were analyzed by both RNA-seq and IHC. Results were then validated in replication IHC cohorts (Figure 1). The development and performance of the different IHC algorithms are detailed in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analyses

First, unsupervised clustering using independent component analysis was applied to the discovery GEP cohort to identify consensus gene expression clusters, which were then explored for their biological relevance and correlation with survival. Functional enrichment analysis of the consensus clusters was performed using gene sets gathered from the MSigDB hallmarks23 and Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project24 (LLMPP) collections and from recently published FL studies,17,25 detailed in the supplemental Methods (paragraph 1.5-1.7). The selected CC17 and CC21 gene cluster signatures were projected into individual cell lineages from a publicly available single-cell RNA-seq atlas of healthy tonsils,26 as detailed in the supplemental Methods (paragraph 1.8). We also tested these signatures in a published single-cell RNA-seq data set from 20 patients with FL27 to score their enrichment in tumor B cells previously identified as malignant (supplemental Methods paragraph 1.9).

A linear predictor score (LPS) classifier, named FL20, was designed to classify samples from the RELEVANCE trial into either MEM-like or GC-like subtype based on the 20 top most discriminant genes from the CC17 and CC21 clusters (supplemental Methods paragraph 1.12). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC AUC) score was used to evaluate the ability to predict the FL20 class from the CC17/CC21 scores (supplemental Figure 6). The enrichment score of the 20 genes constituting FL20 was assessed in tumor B cells from a published single-cell RNA-seq data set of patients with FL27 (supplemental Methods paragraph 1.9). The association between the FL20 classifier and mutational profiles in patients from the RELEVANCE trial was established by direct testing of individual genes and through the training of a random forest (RF) model that predicted the FL20 from the mutational profile. This RF model was further validated in an external cohort18 using ROC AUC score (supplemental Methods paragraphs 1.14 and 1.15). FL20 validation was performed using the PRIMA and BCCA cohorts. GeneChip-Robust Multiarray Averaging (GC-RMA) Affymetrix normalized data28 and the GSE119214 data set22 were used (supplemental Methods paragraphs 1.13 and 1.16).

Results

Unsupervised clustering of RNA profiling leads to a COO categorization of 2 FL segments with distinct biological features

RNA-seq profiles were generated to identify homogenous high-risk molecular segments and to characterize their biological underpinning in patients from the RELEVANCE trial (Figure 1). The baseline clinical features of the discovery GEP cohort (n = 324) were slightly different from the remaining RELEVANCE intent-to-treat patients, especially in the number of extranodal sites, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and the type of chemotherapy in the R-chemo arm (supplemental Table 1), but PFS was similar in both cohorts (supplemental Figure 1A). There was a trend toward better PFS among R2-treated patients in the discovery GEP cohort (P = .15; supplemental Figure 1B), which was not observed in the overall RELEVANCE cohort (P = .78).19

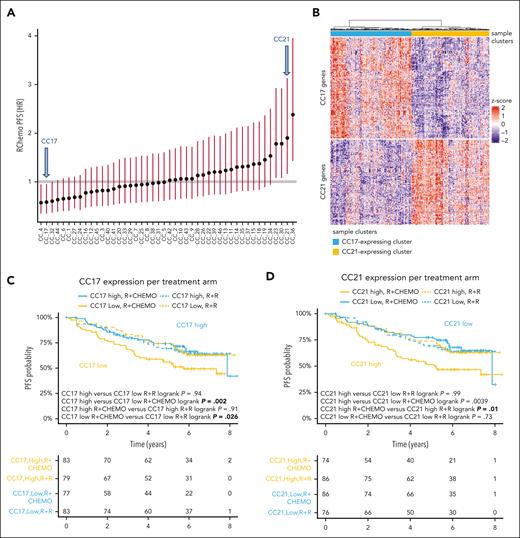

Using the discovery GEP cohort, we performed independent component analysis–based consensus clustering and identified 46 gene clusters (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 2A; supplemental Table 2). Two gene clusters, CC17 and CC21, had anticorrelated signatures (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 2B) and were strongly associated with PFS in the R-chemo treated arm (Figure 2C-D). Gene enrichment analysis associated these clusters with DLBCL COO signatures as follows: CC17 with GCB (LLMPP GCBDLBCL-3; false discovery rate [FDR] = 9.5E-38)23,29 and CC21 with ABC (LLMPP ABCDLBCL-4; FDR = 2.5E-16).23,29 CC21 was also related to Interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4)- and Transcription factor 4 (TCF4)-driven signatures (Figure 3A). Of note, CC17 and CC21 were respectively enriched in the type-A (GCB-like) and type-B (MB-like) FL bulk and single-cell transcriptional signatures described by Wang et al17 (supplemental Table 3).

Properties of the CC21 and CC17 gene clusters. (A) CC21 and CC17 clusters (arrows) were identified among the 46 gene clusters correlated with PFS in the R-chemo arm. The association of each cluster is shown using the corresponding median score as a cutoff. (B) RNA-seq heat map of the discovery GEP cohort. The whole cohort of samples (n = 324) is split into 2 different segments (n = 160 and 164, respectively) based on the expression of CC17 (blue) and CC21 (yellow) gene clusters, which seem to be anticorrelated. (C-D) PFS in the discovery GEP cohort stratified by CC17 (C) and CC21 (D) gene signatures (median cut), split by treatment arm. Low CC17 expression (C) and high CC21 expression as well (D) has adverse impacts.

Properties of the CC21 and CC17 gene clusters. (A) CC21 and CC17 clusters (arrows) were identified among the 46 gene clusters correlated with PFS in the R-chemo arm. The association of each cluster is shown using the corresponding median score as a cutoff. (B) RNA-seq heat map of the discovery GEP cohort. The whole cohort of samples (n = 324) is split into 2 different segments (n = 160 and 164, respectively) based on the expression of CC17 (blue) and CC21 (yellow) gene clusters, which seem to be anticorrelated. (C-D) PFS in the discovery GEP cohort stratified by CC17 (C) and CC21 (D) gene signatures (median cut), split by treatment arm. Low CC17 expression (C) and high CC21 expression as well (D) has adverse impacts.

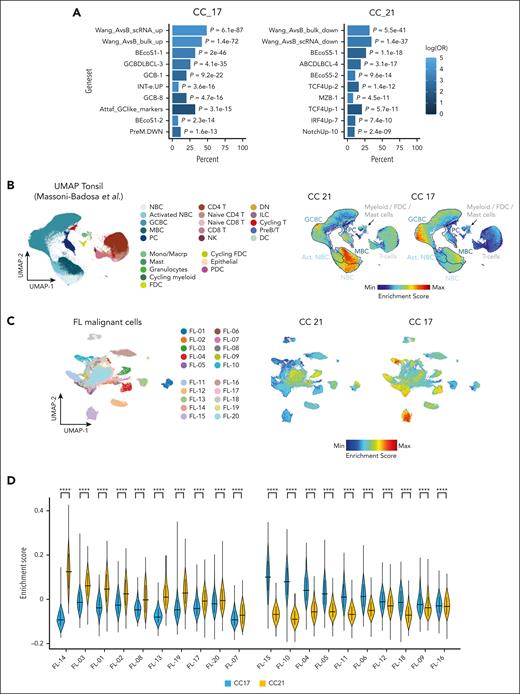

Biological relevance of the CC17 and CC21 gene clusters. (A) The top 10 gene sets enriched for CC17 and CC21 were analyzed against a collection of lymphoma related signatures, including DLBCL COO related signatures.23,29 There was significant overlap of CC17 with GCB-DLCL and normal GC B-cell signatures (left), whereas CC21 was associated with ABC-DLCL and IRF4/TCF4-driven signatures (right). CC17 and CC21 were respectively enriched in the type-A and type-B FL transcriptional signatures described by Wang et al.17 Supplemental Table 3 contains detailed results and gene sets descriptions. (B) A comparative analysis of CC17 and CC21 signatures against single-cell signatures of normal B-cell lineages along the developmental trajectory. We used signatures and scores from the published Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) Tonsil Atlas26 (left panel is a reproduction of figure 1 from Massoni-Badosa et al26). Projections of CC21 and CC17 on the UMAP Tonsil Atlas show overexpression of CC17 and CC21 signatures in distinct maturation states of B cells. Hence, the patient segment defined by CC17 was named GC-like and the segment defined by CC21 was named MEM-like subtype. (C-D) Enrichment score of CC17 and CC21 signatures in an external single-cell RNA-seq data set of patients with FL.27 (C) Enrichment scores for CC21 and CC17 are projected on the UMAP plot of malignant B cells from 20 patients with FL (8111 cells) profiled and annotated according to sample ID. (D) Violin plot showing the mean and standard deviation of the CC21 and CC17 enrichment scores in each patient sample. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, Wilcoxon test with Bonferroni correction. NBC, activated naive B cells; NBC, naive B cells; PC, plasma cells; FDC, follicular dendritic cells.

Biological relevance of the CC17 and CC21 gene clusters. (A) The top 10 gene sets enriched for CC17 and CC21 were analyzed against a collection of lymphoma related signatures, including DLBCL COO related signatures.23,29 There was significant overlap of CC17 with GCB-DLCL and normal GC B-cell signatures (left), whereas CC21 was associated with ABC-DLCL and IRF4/TCF4-driven signatures (right). CC17 and CC21 were respectively enriched in the type-A and type-B FL transcriptional signatures described by Wang et al.17 Supplemental Table 3 contains detailed results and gene sets descriptions. (B) A comparative analysis of CC17 and CC21 signatures against single-cell signatures of normal B-cell lineages along the developmental trajectory. We used signatures and scores from the published Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) Tonsil Atlas26 (left panel is a reproduction of figure 1 from Massoni-Badosa et al26). Projections of CC21 and CC17 on the UMAP Tonsil Atlas show overexpression of CC17 and CC21 signatures in distinct maturation states of B cells. Hence, the patient segment defined by CC17 was named GC-like and the segment defined by CC21 was named MEM-like subtype. (C-D) Enrichment score of CC17 and CC21 signatures in an external single-cell RNA-seq data set of patients with FL.27 (C) Enrichment scores for CC21 and CC17 are projected on the UMAP plot of malignant B cells from 20 patients with FL (8111 cells) profiled and annotated according to sample ID. (D) Violin plot showing the mean and standard deviation of the CC21 and CC17 enrichment scores in each patient sample. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, Wilcoxon test with Bonferroni correction. NBC, activated naive B cells; NBC, naive B cells; PC, plasma cells; FDC, follicular dendritic cells.

Apart from CC17 and CC21, other gene clusters, such as CC4, which was functionally related to a stromal signature, and CC36, which was mainly related to gender, also presented strong associations with PFS. Since the CC4 and CC36 signatures were unrelated to B-cell biology, we eventually focused on CC17 and CC21 because of their strong association with PFS and their potential relevance in tumor biology.

To further investigate these signatures with regard to a putative COO connection, we evaluated their expression in single cells of normal B-cell lineages from reactive tonsils along the developmental trajectory.26 We found that CC17 was predominantly expressed by GC B cells and CC21 by memory B-cells (P < .0001; Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 3). Hence, the patient segment defined by CC17 was defined as GC-like and that by CC21 was defined as MEM-like subtypes.

These signatures were scored in a publicly available single-cell RNA-seq data set encompassing FL tumor tissues,27 which confirmed their ability to discriminate between FL samples at a single-cell level with a balanced distribution of patients enriched in either GC-like or MEM-like features (Figure 3C).

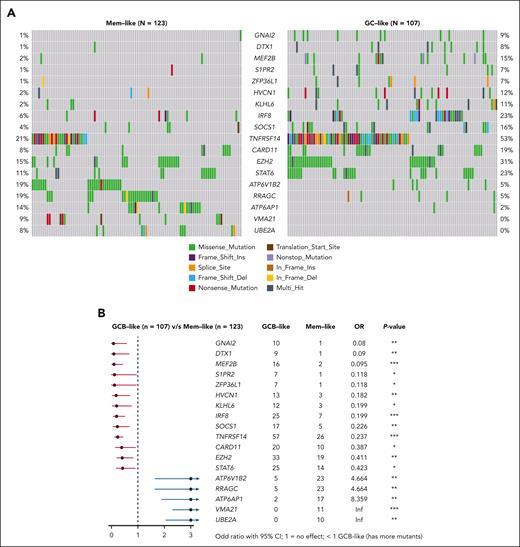

We then performed WES on 242 RELEVANCE samples (including 230 with RNA-seq data). A total of 55 significantly mutated genes were identified using the normalized ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous somatic mutations (dndsCV) (FDR < 0.1).30 This list of significantly mutated genes was further expanded to include 34 additional curated FL-mutated genes from previous studies as detailed in the supplemental Methods and supplemental Table 5. This led to a comprehensive analysis of 89 genes (supplemental Figure 4A-B), including 18 genes that were differentially mutated between GC-like (n = 107) and MEM-like (n = 123) subtypes (Figure 4). Among them, GNAI2, S1PR2, KLHL6, IRF8, SOCS1, TNFRSF14, EZH2, and STAT6, typically mutated in GCB-DLBCL,9 had a higher mutation rate in GC-like than in MEM-like FL, indicative of common genetic drivers between GC-like FL and GCB-DLBCL. The GC-like group also harbored more frequent mutations in hotspots of aberrant somatic hypermutation (supplemental Figure 4C). In contrast, the MEM-like FL subtype displayed a higher mutation rate in genes involved in the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, such as VMA21, ATP6AP1, RRAGC, and ATP6V1B2, indicating a distinct set of genetic drivers and suggesting that this subtype is not the genetic equivalent of ABC-DLBCL within FL.9 The rate of CREBBP missense mutations in the KAT11 domain was significantly higher in MEM-like than in GC-like cases (54% and 33%, respectively; odds ratio, 2.35; P = .002).

Correlations between transcriptomic and mutational profiles. (A) Differences in the mutation profiles between GC-like and MEM-like samples analyzed by WES in 230 FL samples from the discovery GEP cohort. Oncoprints show variants in the 18 significantly mutated genes (SMGs) (out of the 55 SMGs observed in the whole cohort), which were identified as differentially mutated between GC-like and MEM-like subtypes. (B) Forest plot showing gene mutation frequencies between GC-like and MEM-like segments. The squares and horizontal lines represent the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for the corresponding gene. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001.

Correlations between transcriptomic and mutational profiles. (A) Differences in the mutation profiles between GC-like and MEM-like samples analyzed by WES in 230 FL samples from the discovery GEP cohort. Oncoprints show variants in the 18 significantly mutated genes (SMGs) (out of the 55 SMGs observed in the whole cohort), which were identified as differentially mutated between GC-like and MEM-like subtypes. (B) Forest plot showing gene mutation frequencies between GC-like and MEM-like segments. The squares and horizontal lines represent the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for the corresponding gene. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization data (n = 256 samples with RNA-seq data) showed that MYC translocation was enriched in GC-like FL (4.3 % vs 0%; Fisher exact test P = .02) and that BCL6 translocation was more frequent in MEM-like FL (10.9% vs 25.2%; Fisher exact test P = .02) (supplemental Table 6). BCL2-R showed no difference in frequency between subtypes (detected in 83.6% and 89.7% of GC-like and MEM-like FL, respectively; P = .19). Similarly, the 1p36 deletion frequency was not significantly different between the subtypes (14.9% and 17.7% in GC-like and MEM-like FL, respectively).

Using a deconvolution tool,31 we estimated the relative fractions of infiltrating immune cells from RNA-seq data. There was no significant difference in malignant B cells, T cells, or other immune cell populations between GC-like and MEM-like FL. However, there was a trend toward less abundant malignant B cells and more T cells in those patients with weaker CC17 or CC21 scores (supplemental Figure 5).

FL20 gene classifier and clinical features of GC-like and MEM-like subtypes

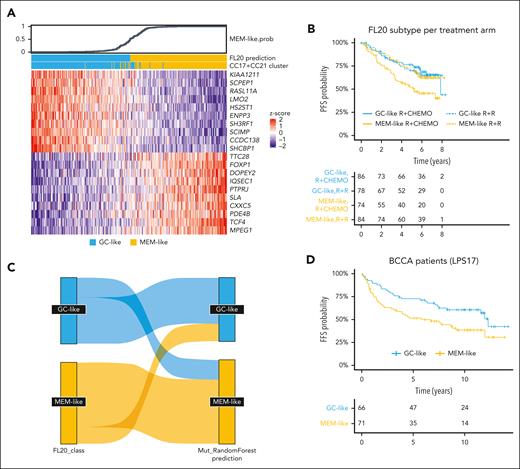

We selected the top 10 most discriminating genes from CC17 and CC21 and generated a 20-gene LPS, named FL20 (Figure 5A; supplemental Tables 7-9). In the discovery GEP cohort, GC-like and MEM-like samples that were classified by FL20 were consistent with those classified by CC17 and CC21 (AUC > 0.99; supplemental Figure 6).

Properties of the FL20. (A) Heat map showing the expression levels of the 20 genes (rows) used in the FL20 classifier to assign patients (columns) into GC-like (blue) and MEM-like (yellow) classes/subtypes. The top panel shows the FL20-assigned probability of a sample being MEM-like. (B) PFS of R-chemo and R2-treated patients stratified by FL20 in the RELEVANCE discovery GEP cohort (n = 322, the 2 remaining patients were untreated and excluded from PFS analysis). MEM-like samples defined by FL20 have worse outcome than those classified as GC-like when treated by R-chemo (P = .0023). (C) Sankey plot showing the correlation between classes/subtypes defined by FL20 (left) and the class prediction performed by an RF model derived from mutation profiles (right). The RF classifier achieved 79% sensitivity and 70% specificity for MEM-like classification in the RELEVANCE discovery GEP cohort. (D) Failure-free survival of R-chemo treated patients stratified by LPS17 (a 17 gene-adapted version of FL20; supplemental Methods) in the BCCA replication cohort (n = 137). BCCA patients classified as MEM-like have a worse outcome than those classified as GC-like in a way similar to RELEVANCE patients (P = .017).

Properties of the FL20. (A) Heat map showing the expression levels of the 20 genes (rows) used in the FL20 classifier to assign patients (columns) into GC-like (blue) and MEM-like (yellow) classes/subtypes. The top panel shows the FL20-assigned probability of a sample being MEM-like. (B) PFS of R-chemo and R2-treated patients stratified by FL20 in the RELEVANCE discovery GEP cohort (n = 322, the 2 remaining patients were untreated and excluded from PFS analysis). MEM-like samples defined by FL20 have worse outcome than those classified as GC-like when treated by R-chemo (P = .0023). (C) Sankey plot showing the correlation between classes/subtypes defined by FL20 (left) and the class prediction performed by an RF model derived from mutation profiles (right). The RF classifier achieved 79% sensitivity and 70% specificity for MEM-like classification in the RELEVANCE discovery GEP cohort. (D) Failure-free survival of R-chemo treated patients stratified by LPS17 (a 17 gene-adapted version of FL20; supplemental Methods) in the BCCA replication cohort (n = 137). BCCA patients classified as MEM-like have a worse outcome than those classified as GC-like in a way similar to RELEVANCE patients (P = .017).

When FL20 was applied to a single-cell FL data set (n = 20),27 the malignant B cells displayed differential GC-like/MEM-like scores that were sufficient to determine their classes (supplemental Figure 7A). Despite the intratumoral heterogeneity observed in these samples, a dominant signature prevailed in every sample except one (supplemental Figure 7B-C).

In the RELEVANCE R-chemo arm, the 6-year PFS of patients with MEM-like FL (45%; 35-59) was significantly shorter than that of patients with GC-like FL (69%; 59-80; hazard ratio [HR], 2.13; 1.30-3.51; P = .0023) (Figure 5B). This outcome difference mainly originated from the subgroup of patients with a FLIPI of ≥2 (n = 160) (HR, 2.11; 1.28-3.48; P = .0029) (supplemental Figure 8A). In a multivariate model that included FLIPI and gender, the association between the FL subtype and outcome remained significant for the R-chemo-treated patients (adjusted HR, 2.06; 1.24-3.4; P = .005), and the treatment dependence also remained significant (interaction subtype × treatment P = .041). GC-like cases were more frequent in older patients (P = .004), whereas MEM-like cases were associated with bone marrow involvement (P < .001) and a greater number of invaded nodal areas (P < .001). FL20 subtyping was not correlated with FLIPI, progression of disease within 24 months (POD24), nor histological grade in this cohort (supplemental Figure 8B).

In the R2 arm, both segments had a comparable PFS (62%; 52-74 vs 65%; 54-77; HR, 1.04; 0.61-1.77; P = .88) (Figure 5B). R2, when compared with R-chemo, had a more favorable outcome in patients with MEM-like FL (HR, 0.54; 0.34-0.88; P = .011) but not in patients with GC-like FL (P = .76).

We also evaluated whether the mutational profile could predict the FL20 subtypes by training a RF predictor (supplemental Methods) using RELEVANCE samples with both WES and RNA-seq data available (n = 230). The model achieved 79% sensitivity and 70% specificity for MEM-like classification (Figure 5C; supplemental Figure 9A-B). This result was validated using an external published cohort of patients with FL with both whole-genome sequencing and RNA-seq profiles (n = 104),18 and in this cohort, the RF model predicted a MEM-like subtype with 81% sensitivity and 68% specificity (supplemental Figure 9C-D). Discordance between RF class vote and FL20 score tended to be for those cases with a lower prediction score that was closer to the threshold in both models (data not shown). However, the mutation-based RF model was not correlated with PFS in the RELEVANCE trial patients who were treated with R-chemo (P = .73).

Once FL20 was fixed, its prognostic value was tested and validated in an independent FL cohort treated with R-chemo, namely GSE119214 (n = 137), hereafter referred to as BCCA.22 Of the 20 genes that defined FL20, 3 were missing from the BCCA data set.22 Hence, an adjustment of the classifier was required and led to the creation of LPS17, a 17-gene adapted version of FL20 (supplemental Figure 10A). In the BCCA cohort, patients with MEM-like FL were associated with an inferior failure-free survival (HR, 1.78; 1.1-2.87; P = .017) and overall survival (HR, 2.13; 1.18-3.82; P = .0098) than patients with GC-like FL (Figure 5D). In addition, FL20 was applied to the PRIMA cohort that was composed of R-chemo–treated patients28 (supplemental Figure 10B). In the whole cohort, patients with MEM-like FL did not have a significantly different PFS than those with GC-like FL (P = .19; n = 134; supplemental Figure 10C). However, when considering only patients with a FLIPI of ≥2 (n = 111), patients with MEM-like FL were associated with a shorter PFS than those with GC-like FL (HR, 1.72; 1.01-2.93; P = .042) (supplemental Figure 10D-E), similar as what was observed in the RELEVANCE cohort. This association between FL20 and PFS remained significant in a multivariable Cox model (HR, 1.79; 1.02-3.2; P = .039) (supplemental Figure 10F). The distribution of the FL20 scores was similar between the different cohorts (supplemental Figure 11).

Correlations between the FL subtypes and DLBCL COO subtypes

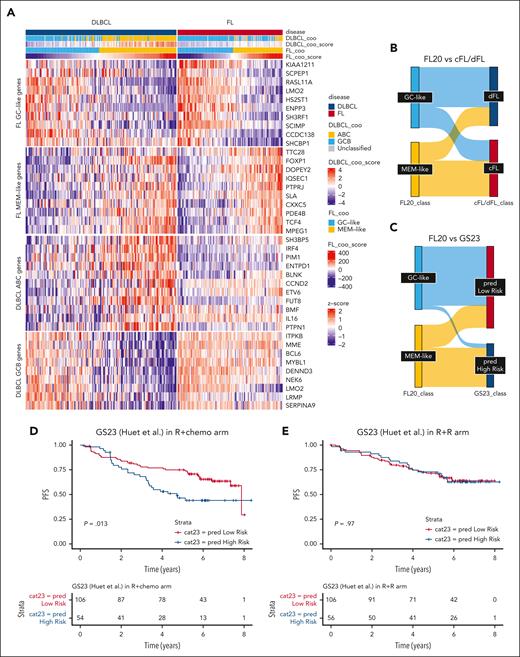

We asked how FL classification by FL20 may be compared with DLBCL COO classification, as implemented by Reddy,7 in a mixed population of patients with DLBCL or FL.

Using a published series of RNA-seq data from Dreval et al,18 we showed that almost all patients with FL (n = 55 of 56) that were classified as GC-like by FL20 were accordingly classified as GCB by Reddy scoring,7 whereas only a few cases of patients with FL (6 of 50) who were classified as MEM-like were called as ABC (Figure 6A). The majority of patients with MEM-like FL were either GCB or unclassified by Reddy scoring.7 In contrast, within the same series,18 FL20 was able to split DLBCL samples (n = 152) into MEM-like and GC-like subgroups similar to the ABC- and GCB- subsets obtained by Reddy scoring (Figure 6A). Overall, these data indicate that FL MEM-like cases are not simply a reflection of the ABC signatures found in DLBCL and that the GC signature used for DLBCL subtyping is not able to discriminate GC-like FL cases.

FL20 compared with other FL and DLBCL classifiers. (A) Heat map depicting a mixed series of FL (top row, pink) and DLBCL (top row, blue) samples (columns) with available RNA-seq data from Dreval et al.18 Genes (rows) have been grouped in different categories, that is, FL20 GC-like genes, FL20 MEM-like genes, and genes belonging to the DLCL COO classifier from Reddy et al.7 All samples have been classified according to either the DLCL COO classifier from Reddy et al7 (second row from top) or FL20 (fourth row from top). Consequently, almost all FL samples classified as GC-like by FL20 are accordingly classified as GCB by Reddy scoring7; however, only a few FL samples classified as MEM-like are called as ABC. The majority of patients with MEM-like FL are either GCB or unclassified by Reddy scoring.7 Overall, FL20 is able to split DLBCL samples into MEM-like and GC-like subgroups similar to the ABC and GCB subsets obtained by Reddy scoring. (B) Sankey plot using a previously published FL series with RNA-seq and genome sequencing data.18 When RNA-seq stratification according to FL20 (into GC-like, blue and MEM-like, yellow) was applied to this series, there was a partial overlap between the FL20 classification and the dFL (dark blue) vs cFL (pink) mutational classification from Dreval et al.18 (C) Correlations between the classification of FL samples according to either GS23 or FL20 predictors. GS23 was previously described to discriminate between patients with high-risk and those with low-risk FL.28 There was a significant overlap between these 2 FL classifiers derived from messenger RNA signatures, but discrepancies were observed for samples simultaneously classified as low-risk (GS23) and MEM-like (FL20). (D-E) PFS in the RELEVANCE discovery cohort as stratified by GS2328 in the R-chemo (P = .013) (D) and R2 (E) arms (P = .97).

FL20 compared with other FL and DLBCL classifiers. (A) Heat map depicting a mixed series of FL (top row, pink) and DLBCL (top row, blue) samples (columns) with available RNA-seq data from Dreval et al.18 Genes (rows) have been grouped in different categories, that is, FL20 GC-like genes, FL20 MEM-like genes, and genes belonging to the DLCL COO classifier from Reddy et al.7 All samples have been classified according to either the DLCL COO classifier from Reddy et al7 (second row from top) or FL20 (fourth row from top). Consequently, almost all FL samples classified as GC-like by FL20 are accordingly classified as GCB by Reddy scoring7; however, only a few FL samples classified as MEM-like are called as ABC. The majority of patients with MEM-like FL are either GCB or unclassified by Reddy scoring.7 Overall, FL20 is able to split DLBCL samples into MEM-like and GC-like subgroups similar to the ABC and GCB subsets obtained by Reddy scoring. (B) Sankey plot using a previously published FL series with RNA-seq and genome sequencing data.18 When RNA-seq stratification according to FL20 (into GC-like, blue and MEM-like, yellow) was applied to this series, there was a partial overlap between the FL20 classification and the dFL (dark blue) vs cFL (pink) mutational classification from Dreval et al.18 (C) Correlations between the classification of FL samples according to either GS23 or FL20 predictors. GS23 was previously described to discriminate between patients with high-risk and those with low-risk FL.28 There was a significant overlap between these 2 FL classifiers derived from messenger RNA signatures, but discrepancies were observed for samples simultaneously classified as low-risk (GS23) and MEM-like (FL20). (D-E) PFS in the RELEVANCE discovery cohort as stratified by GS2328 in the R-chemo (P = .013) (D) and R2 (E) arms (P = .97).

Correlations between the FL20 subtypes and other molecular classifications

Two genetic FL subtypes called DLBCL-like (dFL) and constrained (cFL) were recently identified using WGS by Dreval et al18 but without any reported association with PFS. Among patients with FL from this study,18 we observed a partial overlap between the FL20 transcriptomic classification and the cFL/dFL genetic classification with 66% of GC-like samples classified as dFL and 66% of MEM-like samples classified as cFL (P = .0017; Figure 6B). Altogether, within the Dreval cohort,18 the agreement was 74% between FL20 and the mutation-based RF predictor, 67% between FL20 and the cFL/dFL classification (assuming cFL corresponds to MEM-like and dFL corresponds to GC-like), and 66% between the mutation-based RF predictor and the cFL/dFL classification (supplemental Figure 12).

We also assessed the correlation of FL20 with 2 previously reported prognostic signatures. The 23 gene score (GS23), developed from the PRIMA trial,28 shared 2 genes with CC17 and 6 genes with CC21. GS23 seemed to be less efficient in identifying patients with MEM-like FL in the RELEVANCE discovery GEP cohort (Figure 6C). It was associated with a shorter PFS in the R-chemo arm, but this was less significant than the association observed with FL20 (HR, 1.84; 1.13-3.01; P = .013; Figure 6D). Like FL20, GS23 did not show significance for the R2 arm (P = .97; Figure 6E).

The recently described GS33 signature16 shared 9 and 3 genes with CC17 and CC21, respectively. GS33 was not correlated with PFS in the whole RELEVANCE cohort (P = .6), nor in the R-chemo or R2 arm (P = .11 and P = .39, respectively) (supplemental Figure 13).

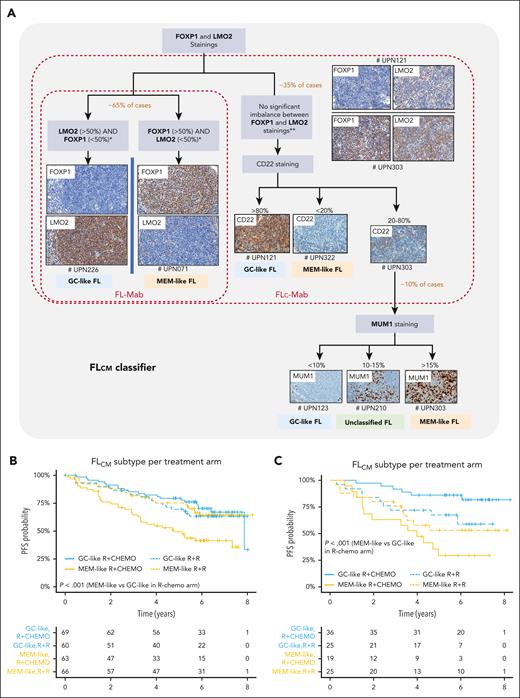

IHC-based classifier FLcm as a surrogate for FL20

An IHC assay was developed using FOXP1, LMO2, CD22, and MUM1 antibodies to serve as an FL20 surrogate for routine clinical practice. We named this classifier FLcm, using the first letter of each marker. The rationale and conception of this algorithm are detailed in the supplemental Methods. Briefly, the algorithm starts with FOXP1 and LMO2 staining; both genes are strong drivers for FL20 but for different segments. If there is a clear difference between FOXP1 and LMO2 immunostainings (ie, one <50% and the other one >50% with a mandatory gap of at least 20%), the sample is typed either as MEM-like (FOXP1+ >50% and LMO2– <50%) or GC-like (FOXP1– <50% and LMO2+ >50%) FL. In case of no clear difference, CD22 is added, and strong CD22 staining (>80%) is associated with GC-like whereas negative staining (<20%) is associated with MEM-like FL. In case of moderate CD22 positivity (20% to 80%), MUM1 is added as the fourth and final marker with a positivity above 15% being associated with MEM-like FL and staining less than 10% being associated with GC-like FL (Figure 7A; supplemental Figure 14).

Immunohistochemical FLcm algorithm and its association with clinical outcome. (A) The FLcm algorithm was developed from the RELEVANCE discovery IHC cohort (n = 264) to classify FFPE biopsy samples into MEM-like or GC-like FL. FOXP1, LMO2, CD22, and MUM1 antibodies were used according to a sequential and hierarchical order starting with both FOXP1 and LMO2 staining, which allowed classification of 65% of samples. If there is a clear difference between these 2 immunostainings (mandatory gap >20% between FOXP1 and LMO2 staining), the sample is typed as either MEM-like (FOXP1+/LMO2–) or GC-like (FOXP1–/LMO2+) FL. If there is no clear difference between LMO2 and FOXP1 staining (ie, both FOXP1 <50% and LMO2 <50 % or both FOXP1 >50% and LM02 >50%), a strong CD22 staining calls for GC-like, whereas a weak or negative staining calls for MEM-like FL. In case of moderate CD22 positivity, MUM1 is added as the fourth and final marker. The different steps, cutoff points, and algorithmic processes are depicted. The brown and red frames delineate simpler combinations derived from FLcm, called FLc-Mab (using only FOXP1, LMO2, and CD22) and FL-Mab (using only FOXP1 and LMO2), respectively. Representative immunostainings in RELEVANCE FL samples (# unique patient number, UPN) are shown. (B) PFS curves for the RELEVANCE discovery IHC cohort (n = 258, 6 patients including 4 unclassified cases and 2 untreated patients were excluded) and (C) PFS curves for the RELEVANCE replication IHC cohort (n = 105, 11 patients including 8 unclassified cases and 3 untreated patients were excluded) after stratification using the FLcm algorithm. Both cohorts show significant difference in PFS between patients with GC-like FL and those with MEM-like FL treated by R-chemo.

Immunohistochemical FLcm algorithm and its association with clinical outcome. (A) The FLcm algorithm was developed from the RELEVANCE discovery IHC cohort (n = 264) to classify FFPE biopsy samples into MEM-like or GC-like FL. FOXP1, LMO2, CD22, and MUM1 antibodies were used according to a sequential and hierarchical order starting with both FOXP1 and LMO2 staining, which allowed classification of 65% of samples. If there is a clear difference between these 2 immunostainings (mandatory gap >20% between FOXP1 and LMO2 staining), the sample is typed as either MEM-like (FOXP1+/LMO2–) or GC-like (FOXP1–/LMO2+) FL. If there is no clear difference between LMO2 and FOXP1 staining (ie, both FOXP1 <50% and LMO2 <50 % or both FOXP1 >50% and LM02 >50%), a strong CD22 staining calls for GC-like, whereas a weak or negative staining calls for MEM-like FL. In case of moderate CD22 positivity, MUM1 is added as the fourth and final marker. The different steps, cutoff points, and algorithmic processes are depicted. The brown and red frames delineate simpler combinations derived from FLcm, called FLc-Mab (using only FOXP1, LMO2, and CD22) and FL-Mab (using only FOXP1 and LMO2), respectively. Representative immunostainings in RELEVANCE FL samples (# unique patient number, UPN) are shown. (B) PFS curves for the RELEVANCE discovery IHC cohort (n = 258, 6 patients including 4 unclassified cases and 2 untreated patients were excluded) and (C) PFS curves for the RELEVANCE replication IHC cohort (n = 105, 11 patients including 8 unclassified cases and 3 untreated patients were excluded) after stratification using the FLcm algorithm. Both cohorts show significant difference in PFS between patients with GC-like FL and those with MEM-like FL treated by R-chemo.

When considering the 264 RELEVANCE cases with both RNA-seq and IHC data available that were used to construct the algorithm (discovery IHC cohort, Figure 1), FLcm reached 96.6% (255/264) concordance with FL20 with 5 FL20 MEM-like samples misclassified by FLcm as GC-like and 4 unclassified cases. The reproducibility was assessed by 2 pathologists (C.L. and L.X.) and showed a good inter-pathologist agreement (kappa = 0.773; 0.695-0.851; supplemental Methods paragraph 1.17).

The PFS profile generated by FLcm classification was consistent with that of FL20 for the GC-like and MEM-like subtypes in both arms (P < .001; Figure 7B). This prognostic value was validated in a separate RELEVANCE set (n = 116, replication IHC cohort 1) with no RNA-seq data available (supplemental Figure 15A; supplemental Table 10). The difference in survival between GC-like and MEM-like FL was confirmed (P < .001; Figure 7C), but the benefit of R2 treatment in patients with MEM-like FL was not significant in this cohort (P = .2). FLcm classification of patients with a FLIPI ≥2 who were treated with R-chemo in the PRIMA study (n = 151, IHC replication cohort 2) also produced a significant PFS difference between GC-like and MEM-like segments (P < .0001) (supplemental Figure 15B).

This association between FLcm and prognosis remained significant when a multivariable Cox model was used in the discovery IHC cohort (P < .001; HR, 2.69) and in the IHC replication cohorts 1 (P < .001; HR, 6.4) and 2 (P < .001; HR, 2.9).

Simpler combinations derived from FLcm were evaluated, called FLc-Mab (using only FOXP1, LMO2, and CD22) and FL-Mab (using only FOXP1 and LMO2) (supplemental Methods paragraph 1.17).Their premise was that equivocal samples after the CD22 step (for FLc-Mab) or after the FOXP1/LMO2 step (for FL-Mab) remained unclassified (Figure 7A). In the discovery IHC cohort, a significant difference was observed between R-chemo–treated patients with GC-like segments and those with MEM-like segments (P = .005 and P = .025 for FLc-Mab and FL-Mab, respectively; supplemental Figure 16). Among patients with MEM-like FL, a better PFS was observed among those treated with R2 than among those treated with R-chemo (P = .014 and P = .005 for FLc-Mab and FL-Mab, respectively). However, the proportion of unclassified cases (n = 27 [10%] and n = 79 [30%] for FLc-Mab and FL-Mab, respectively) was higher when compared with FLcm (n = 4 [2%]).

The significant correlations between FL-Mab or FLc-Mab subtyping and PFS were confirmed in both independent IHC validation cohorts 1 and 2 (supplemental Figures 17 and 18) and remained significant in a multivariate analysis that included FLIPI.

Overall, the IHC data indicate that an algorithm that used 4 antibodies (FLcm), as well as simper versions that used 3 (FLc-Mab) or 2 (FL-Mab) antibodies, can be used to stratify most patients with FL with prognostic correlations similar to FL20 but at the cost of increasing the number of unclassified cases.

Discussion

Using GEP and consensus clustering in this study, we identified 2 gene expression signatures suggestive of normal MEM or GC B cells that can be used to stratify FL tumors into MEM-like and GC-like subtypes with different clinical outcomes and sensitivity to IC. From these signatures, we derived an optimized 20-gene predictor, called FL20, and an IHC algorithm, called FLcm, for FL subtyping.

Our group previously described a gene expression signature, GS23,28 suggestive of adverse PFS in IC-treated patients, but the biological relevance of GS23 was unclear. The statistical value of GS23 to identify patients with MEM-like FL was lower than that of FL20, nor was it transposable in routine IHC diagnosis. The molecular classification developed in this study provides significant novelty and improvements over previously reported ones because it simultaneously provides a prognostic PFS based on tumor biology, the ability to identify patients who can benefit from lenalidomide-rituximab combination treatment, and the possibility of being translated into a convenient IHC tool for routine practice.

This classification tool represents a comprehensive refinement of previous attempts.16-18,28,32 GC-like and MEM-like subtypes are indeed reminiscent of the A and B FL patterns previously described in mass cytometry single-cell experiments that displayed a profile that resembled GC B cells and memory B cells, respectively.17 In addition, the mutational patterns of GC-like and MEM-like subtypes share significant similarities with the recently reported dFL and cFL categories,18 although the degree of overlap remains uncertain because our exome sequencing did not cover the noncoding regions that influence the cFL/dFL distinction.18 A major difference, however, is that our FL20-based GC/MEM classification is correlated with PFS. In contrast, despite correlations with histological transformation, the A/B distinction and the dFL/cFL subdivision were not reported to be associated with survival.17,18

GC-like FLs showed downregulation of IRF4 expression and overexpression of IRF4-repressed genes such as CIITA, HLA-DM, and HLA-DO. In contrast, MEM-like FLs displayed overexpression of IRF4 and genes expressed in normal MEM B cells17,26 and, to a much lesser extent, in naive B cells and dark zone GC B cells.8,17,25,33 This is in accordance with previously published transcriptomic signatures of adverse outcome for IC-treated patients, which were enriched in genes expressed in activated or GC dark zone B cells.32 The relationship between normal MEM B cells and some FL tumors is consistent with the observation of a small component of MEM B-cell precursors within the GC.25

The genetic profile of GC-like FLs, including a high frequency of mutations in GNAI2, S1PR2, KLHL6, IFR8, SOCS1, TNFRSF14, EZH2, and STAT6, is reminiscent of GCB-type DLBCLs. When compared with the classic FL profile, GC-like FLs showed underrepresentation of KMT2D and overrepresentation of SOCS1 mutations, suggesting preferential activation of JAK/STAT signaling. In contrast, MEM-like FLs exhibited a higher frequency of mutations that targeted RRAGC and v-ATPases-coding genes like ATP6AP1, ATP6V1B2, and VMA21. ATPases mutations maintain autophagic flux and mTOR in an active state.34,35 This mutational pattern seems to be different from that of ABC-DLBCLs, characterized by mutations that trigger other genes like CD79A/B and MYD88.10 When compared with GC-like cases, MEM-like FLs also displayed a lower frequency of mutations within aberrant somatic hypermutation target genes and higher numbers of missense mutations within the CREBBP KAT domain, which both are features reminiscent of the recently reported cFL.18

Overall, our findings showed a strong relationship between GC-like FL and GCB-DLBCL but not between MEM-like FL and ABC-DLBCL. Using a mixed population of patients with DLBCL or FL,18 we showed indeed that almost all patients with FL who were classified as GC-like by FL20 were accordingly classified as GCB by Reddy scoring,7 whereas only a few cases of patients with FL who were classified as MEM-like were considered as ABC by the same DLBCL scoring. This suggests that the GC signature used for DLBCL subtyping is not able to identify GC-like FL. The majority of patients with MEM-like FL were either GCB or unclassified, which indicates that, despite belonging to the MEM-like category, these FL tumors do not share much biology with ABC-DLBCL. In contrast, FL20 was able to split DLBCL samples into MEM-like and GC-like groups similar to those obtained by Reddy scoring. This is consistent with recent data suggesting that most ABC-DLBCLs originate from pre-MEM B cells.8

Our data suggest that patients with MEM-like FL have worse outcomes when treated with R-chemo but could benefit from alternative therapy, such as lenalidomide in combination with rituximab. Lenalidomide binds the E3-ligase substrate receptor, cereblon, which leads to ubiquitination and degradation of the Aiolos/Ikaros transcription factors.36 This upregulates interferon-stimulated genes, triggering apoptosis preferentially in ABC-DLBCL cell lines37-39 in accordance with clinical data of enhanced lenalidomide activity in ABC-DLBCL.40,41 The observed lenalidomide sensitivity of the MEM-like FL subtype is reminiscent of the ABC-DLBCL bias for lenalidomide. This suggests prospects of improved anti-lymphoma activity with more potent Aiolos/Ikaros degraders, such as golcadomide, which are underway.

Of note, our results, obtained in patients who were treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), may not apply to R-bendamustine treated patients. Such patients were indeed absent in the discovery GEP cohort. Because the value of most FL prognostic markers is dependent on the type of treatment,42 future assessment of the prognostic nature of FL20 in patients treated with various first-line regimens, including R-bendamustine and soon bispecific antibodies, is warranted.

Although FL20 can be applied to any other cohort, it might be influenced by the heterogeneity of the GC-like/MEM-like distribution between cohorts, which should be acknowledged as a limitation of this approach. In addition, our broad GEP data revealed gene clusters other than CC17 and CC21 that had a statistically significant impact on PFS and deserve further exploration in forthcoming studies.

Finally, we showed that IHC represents a surrogate for RNA-seq for FL subtyping in routine practice. We developed an algorithm called FLcm in which immunodetection of FOXP1, LMO2, CD22, and MUM1 is used, and this provided a correlation with survival similar to that provided by RNA-seq. This expands previous reports that suggested that MUM1 and FOXP1 immunodetections are associated with poor prognosis in IC-treated patients with FL.32,43,44 The simplified versions of FLcm that use only 3 or 2 antibodies, namely FLc-Mab and FL-Mab, seem to be more convenient for identifying patients with FL who can benefit from non-IC treatment. However, this comes at the cost of high proportions of unclassified cases. Overall, the FLcm algorithm or its simpler variants could be thus used to predict the outcome of IC treated–patients in daily practice and to select alternative treatment options.

A limitation of our study resides in the apparent discrepancy between the RELEVANCE trial that showed similar PFS outcomes for the R-chemo and the R2 arms in the entire intent-to-treat population and our analysis in the RELEVANCE discovery GEP cohort that showed that a distinct subgroup of patients does better with R2. This might be explained by a trend toward better PFS among R2-treated patients observed in the RELEVANCE discovery GEP cohort, although this trend was not visible in the entire RELEVANCE cohort.19

In conclusion, FL tumors can be classified into MEM- or GC-like subtypes with biological and prognostic significance, and a simple IHC algorithm is able to subtype FL using routine biopsies, thereby representing a promising tool for personalized medicine approaches. Patients with MEM-like FL display inferior outcomes when treated with IC, but alternative treatments, like lenalidomide, could overcome this adverse prognosis. In this respect, bispecific antibodies and/or immunomodulating agents, like next generation cereblon E3 ligase modulators, may represent a new avenue of therapy that should be evaluated in this population with unmet needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank patients, families, caregivers, and investigators who participated in the RELEVANCE clinical study, the Lymphoma Academic Research Organisation (LYSARC), and the numerous research and study groups, including the Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group, the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group, the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group, the Lymphoma Study Association, and the Grupo Español de Linfomas y Trasplantes de Médula Ósea, that participated in the study. The authors thank the international board of expert pathologists (Danielle Canioni, Catherine Chassagne-Clement, Peggy Dartigues, and Bettina Fabiani) who provided histopathological review at the Lymphoma Study Association pathology institute, Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil, France.

This work was supported by Bristol Myers Squibb, LabEx Toulouse Cancer (ANR-11- LABX- 0068), and LYSARC.

Authorship

Contribution: C.L., B.T., P.T., S.S., A.K.G., and L.X. collected data; C.L., B.T., P.T., S.S., C.C.H., A.K.G., B.L., A.B., S.R., J.-P.C., and L.X. analyzed the data and made the figures; C.L., B.T., P.T., S.S., C.C.H., A.K.G., F.M., and L.X. designed the research and wrote the paper; C.L., C.C.H., P.T., N.V.A., A.K.G., and L.X. performed experiments; B.T., S.S., A.B., S.R., and J.-P.C. provided bioinformatics analysis; S.H., M.E.S., A.G., and L.C. provided expert analysis; and C.L., L.X., and F.M. provided patient samples and clinical information.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.T., S.S., M.E.S., C.C.H., and A.K.G. are current employees of Bristol Myers Squibb. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Luc Xerri; Département de Bio-Pathologie, Institut Paoli-Calmettes, 232 Blvd Sainte Marguerite; 13273 Marseille, France; email: xerril@ipc.unicancer.fr; and Camille Laurent; Département de Bio-Pathologie, Institut Universitaire du Cancer de Toulouse, 1 Ave I Joliot, 31059 Toulouse, France; email: laurent.c@chu-toulouse.fr.

References

Author notes

C.L., P.T., and B.T. contributed equally to this study.

A.K.G., F.M., and L.X. contributed equally to this study.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Luc Xerri (xerril@ipc.unicancer.fr).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal