The European LeukemiaNet 2024 risk-stratification guidelines for patients with acute myeloid leukemia receiving hypomethylating agents combined with venetoclax were recently published. This analysis demonstrates reclassification and incorporation of new gene mutations in the present model can further improve and individualize prognostication.

TO THE EDITOR:

The recently published 4-gene risk classifier and European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2024 risk stratification criteria (ELN24), stratifying patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated with hypomethylating agents (HMA) combined with venetoclax (HMA+VEN) based on the presence of mutations in 4 genes (FLT3-ITD, N/KRAS, and TP53), is an important and welcomed contribution to the field.1-3 Prior prognostication models were predominantly based upon patients aged <60 years treated with intensive anthracycline- and cytarabine-based regimens and do not adequately risk stratify patients receiving HMA+VEN. Because relapse remains the major cause of treatment failure, and those who are refractory have very poor outcomes, the ability to further improve long-term risk stratification in patients with AML receiving HMA+VEN is critically important.4

After the creation of the 4-gene classifier, pertinent questions remain, including: (1) whether patients with VEN-sensitive mutations (eg, NPM1, DDX41, or IDH1/2) without co-occurring signaling mutations should encompass a separate subgroup. Early reports suggest that some “super-responders” in this higher-benefit subset may be able to discontinue therapy after a finite duration5-7; (2) whether “other” mutations not currently classified truly represent favorable-risk markers akin to NPM1, IDH1/2, or DDX41 mutations; (3) whether the differential sensitivity observed with NRAS and KRAS in preclinical models translates to clinical outcomes8,9; and (4) whether alternative RAS/receptor tyrosine kinase pathway mutations (ie, CBL, NF1, and PTPN11) similarly affect prognosis.1

We conducted a retrospective multicenter analysis of 279 patients treated with frontline HMA+VEN combinations across 3 US academic medical centers to validate the newly published ELN24 risk-stratification criteria and address these outstanding questions.2 An additional 430 patients treated with HMA+VEN combinations within UK NHS hospitals were independently analyzed for confirmation of the initial results. Additional statistical considerations can be found in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website. All research was conducted after approval by the participating sites’ institutional review boards and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

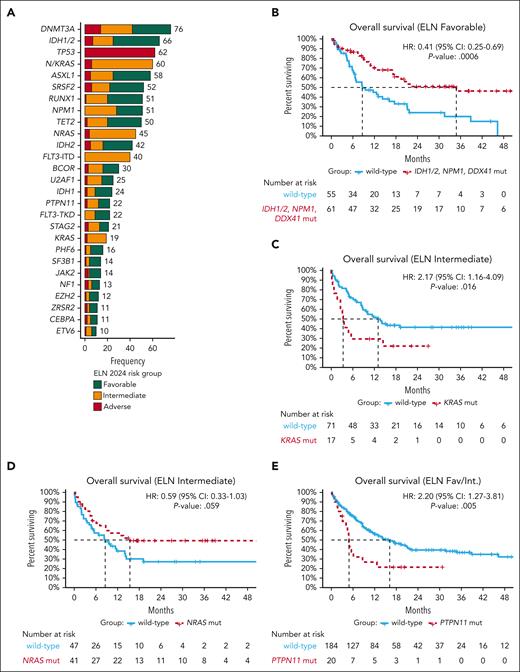

Demographics are displayed in supplemental Table 1. In contrast to the VIALE-A population, the included population was younger, with a median age of 72 years (range, 20-89) with 62% (n = 165) of patients aged ≥70 years and 17% (n = 46) undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Baseline molecular demographics were available for 95% (266/279) of the cohort and were favorable in 44% (116/266), intermediate in 33% (88/266), and adverse in 23% (62/266) per ELN24 criteria. Frequent mutations identified at diagnosis included IDH1/2 (n = 66), NPM1 (n = 51), N/KRAS (n = 60), FLT3-ITD (n = 40), and TP53 (n = 62; Figure 1A; supplemental Table 2). More patients classified as intermediate risk (28% [25/88]) demonstrated surface expression of ≥3 markers of monocytic differentiation per ELN22 criteria, consistent with enrichment of this phenotype in patients with signaling mutations.10

Genetic landscape and survival of patients treated with HMA+VEN combinations. (A) The genetic landscape of 266 patients treated with HMA+VEN combinations, displaying the frequency of mutations (mut) present in ≥10 patients. Notably, most muts (other than those used for current risk-group assignment) could be found across all ELN24 risk groups. (B) Within the ELN24 favorable-risk subgroup, patients with mutated NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, or DDX41 experienced particularly favorable survival compared with other included patients. (C-D) Within the ELN24 intermediate-risk subgroup, KRAS muts but not NRAS muts were associated with inferior survival. (E) When evaluating other RAS/receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathway gene mut’s impact on survival, PTPN11 muts correlated with inferior outcomes. CI, confidence interval; Fav/Int, favorable/intermediate risk; HR, hazard ratio.

Genetic landscape and survival of patients treated with HMA+VEN combinations. (A) The genetic landscape of 266 patients treated with HMA+VEN combinations, displaying the frequency of mutations (mut) present in ≥10 patients. Notably, most muts (other than those used for current risk-group assignment) could be found across all ELN24 risk groups. (B) Within the ELN24 favorable-risk subgroup, patients with mutated NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, or DDX41 experienced particularly favorable survival compared with other included patients. (C-D) Within the ELN24 intermediate-risk subgroup, KRAS muts but not NRAS muts were associated with inferior survival. (E) When evaluating other RAS/receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathway gene mut’s impact on survival, PTPN11 muts correlated with inferior outcomes. CI, confidence interval; Fav/Int, favorable/intermediate risk; HR, hazard ratio.

Complete response (CR)/CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi) was attained in 67%, 67%, and 56% of patients with ELN24 favorable, intermediate, or adverse-risk disease, respectively, and did not significantly differ across groups. Because favorable and intermediate-risk groups represent composite genetic groups, individual mutations within these groups were assessed for their impact on response. Patients with NPM1 (87% vs 62%; P = .026) or IDH2 mutations experienced increased CR/CRi rates (81% vs 63%; P = .10) whereas KRAS mutations associated with a trend toward decreased CR/CRi rates (47% vs 72%; P = .08).

After a median follow-up of 28 months, median overall survival (OS) was 11.4 months (95% confidence interval, 9.0-14.4). Although shorter than the median OS of 14.7 months reported in VIALE-A, these outcomes mirror other retrospective cohorts, likely reflecting broader patient populations inclusive of study-ineligible patients.3,11-13

Within the ELN24 favorable-risk group, patients with mutated NPM1, IDH1/2, or DDX41 had improved survival vs patients with “other” favorable-risk mutations (median, 34.8 vs 8.6 months; P = .0006), indicating that these latter mutations may be better classified within the intermediate-risk group (Figure 1B). Within the intermediate-risk group, KRAS mutations demonstrated inferior OS (median, 3.3 vs 13 months; P = .016) whereas NRAS mutations were not statistically associated with OS (15.4 vs 8.6 months, P = .059; Figure 1C-D). Among all patients, no significant OS difference was observed based on the presence of mutated FLT3-ITD, although patients with mutated NPM1 and wild-type vs mutated FLT3-ITD had numerically improved OS (supplemental Figure 1). Next, we evaluated whether other signaling kinase mutations prevalent in ≥10 patients (PTPN11 and NF1) across the higher- and intermediate-risk groups (thus excluding TP53-mutated cases) affected OS. PTPN11 mutations were present in 10% (n = 20) of patients and corresponded with shorter OS (median, 4.9 vs 16.2 months; P = .005; Figure 1E).

Recognizing that the prognostic weight of certain genomic drivers varies, and mutations are not mutually exclusive, multivariate analysis was performed adjusting for HCT, given the impact of this treatment modality (supplemental Figure 2A). After accounting for additional mutations that remained significant in multivariate analysis modeling, the ELN24 risk groups were reclassified as favorable (mutated NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, DDX41, and wild-type N/KRAS, PTPN11, FLT3-ITD, and TP53), intermediate (mutated FLT3-ITD, NRAS, or other mutations not classified, and wild-type KRAS, PTPN11, and TP53), or adverse risk (mutated KRAS, PTPN11, or TP53; supplemental Figure 2B).

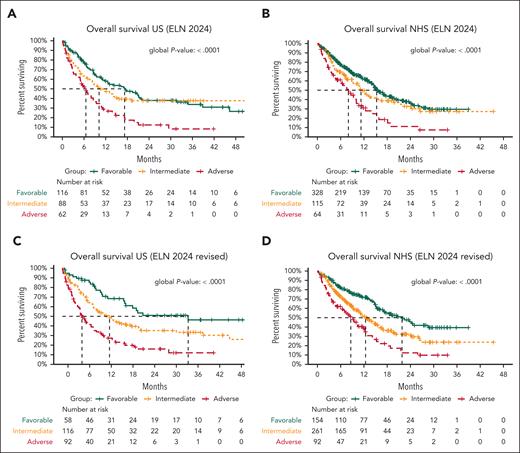

In the US cohort, median OS across ELN24 favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk groups was 17.2, 10.2, and 6.5 months, respectively (Figure 2A). Median OS across the revised favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk groups was 34.8 vs 13.0 vs 5.4 months (Figure 2C). This revised classification better modeled survival outcomes after HMA+VEN than ELN24 (C-index, 0.63 vs 0.59) and improved 24-month OS stratification most within the favorable-risk group (favorable, 51% vs 38%; intermediate, 35% vs 38%; adverse, 16% vs 12%).

Survival based on current and revised ELN 2024 risk-stratification criteria. (A) Current ELN24 criteria risk stratify patients treated with HMA+VEN combinations in the US cohort with median OS of 17.2, 10.2, and 6.5 months across ELN24 favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk groups, respectively. (B) Similar stratification was observed in patients treated with HMA+VEN combinations within the UK National Health Service (NHS) cohort. Notably, in both cohorts, 24-month OS was similar between favorable- and intermediate-risk patients. (C) Using the proposed revised ELN criteria improved OS stratification within the US cohort, with median OS across favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk groups of 34.8 vs 13 vs 5.4 months, respectively. Survival stratification was notably improved between favorable- and intermediate-risk patients at 24 months (51% vs 35%). (D) Similar findings were observed within the UK NHS cohort, with improved survival stratification between favorable- and intermediate-risk groups (24-month OS, 43% vs 31%).

Survival based on current and revised ELN 2024 risk-stratification criteria. (A) Current ELN24 criteria risk stratify patients treated with HMA+VEN combinations in the US cohort with median OS of 17.2, 10.2, and 6.5 months across ELN24 favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk groups, respectively. (B) Similar stratification was observed in patients treated with HMA+VEN combinations within the UK National Health Service (NHS) cohort. Notably, in both cohorts, 24-month OS was similar between favorable- and intermediate-risk patients. (C) Using the proposed revised ELN criteria improved OS stratification within the US cohort, with median OS across favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk groups of 34.8 vs 13 vs 5.4 months, respectively. Survival stratification was notably improved between favorable- and intermediate-risk patients at 24 months (51% vs 35%). (D) Similar findings were observed within the UK NHS cohort, with improved survival stratification between favorable- and intermediate-risk groups (24-month OS, 43% vs 31%).

Improved event-free survival discrimination was also observed using these revised criteria compared with current ELN24 criteria (C-index, 0.62 vs 0.58) with 24-month event-free survival estimates for favorable-, intermediate-, and adverse-risk groups of 49% vs 35%, 26% vs 26%, and 11% vs 5%, respectively (supplemental Figure 3; supplemental Table 3).

These findings were next independently analyzed within the UK National Health Service cohort (N = 430; supplemental Table 4). The revised classification improved OS stratification compared with ELN24 (C-index, 0.60 vs 0.58), most notably between the favorable- and intermediate-risk categories (Figure 2B,D). As in the US cohort, the revised classification improved 24-month stratification most within the favorable-risk group compared with ELN24 (favorable, 43% vs 34%; intermediate, 31% vs 31%; adverse, 12% vs 11%). No considerable difference in survival rates was observed in patients classified as intermediate or adverse risk, suggesting that this regrouping appropriately assigns patients with similar long-term outcomes.

AML is a genetically heterogenous disease, which poses challenges to prognostication based on singular genetic markers.14 Currently, published studies remain underpowered to determine the impact of additional mutations occurring within similar biological pathways. This study scrutinizes the prognostic impact of NRAS, KRAS, and PTPN11 mutations after HMA+VEN and suggests that KRAS and PTPN11 mutations, rather than NRAS mutations, impart a negative survival influence when identified at diagnosis. This is supported by recent clinical data demonstrating no prognostic impact of NRAS mutations when identified at diagnosis in the context of VEN-based therapy in addition to alternative prognostic models and preclinical data demonstrating a negative impact of KRAS, which, like PTPN11, results in MCL1 upregulation and subsequent downregulation of BAX.9,15,16

Importantly, we demonstrate that favorable-risk patients with mutations in DDX41, NPM1, or IDH1/2 experience particularly favorable survival (median, 34.8 months) whereas patients with “other” mutations that are currently considered favorable risk but without mutations in DDX41, NPM1, or IDH1/2, have survival similar to patients classified as ELN24 intermediate risk (8.6 vs 10.2 months). Regrouping of current risk stratification may enable identification of patients who are considered exceptional responders to HMA+VEN and better predict long-term survival.

Although inferior survival has been observed in IDH1- vs IDH2-mutated AML, this is largely based on subgroup analyses from the initial phase 1b/phase 3 studies of HMA+VEN with limited power.17 This analysis demonstrated more favorable outcomes in IDH1-mutated AML without co-occurring signaling mutations, as observed by Döhner et al.1 Thus, in this context, IDH1 could still be considered a favorable-risk marker.

In conclusion, the ELN24 guidelines are a welcome addition to aid risk-stratification in patients with AML treated with lower-intensity therapies. These initial criteria will help lay the groundwork for further development and improvement of a validated prognostic scoring system for HMA+VEN–treated patients. We commend those authors and believe the continued addition of prognostic markers, regrouping of genomic subgroups, and ongoing validation will further individualize prognostication in AML.

Acknowledgments

C.A.L. is supported by an Oregon Clinical and Translational Institute KL2 award (grant KL2TR002370). D.A.P. is supported by the Robert H. Allen MD Chair in Hematology Research and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society’s Career Development Program Scholar in Clinical Research Achievement Award.

Authorship

Contribution: C.A.L., V.I.R., D.T.P., C.M., J.N.S., J.W.T., J.F.Z., and D.A.P. were responsible for data collection in the primary cohort, and drafting and review of the final manuscript; R.S. and R.C. were responsible for drafting and review of the final manuscript; and J. Othman, J. O’Nions, and R.D. were responsible for data collection in the validation cohort, and drafting and review of the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.A.L. receives research funding from AbbVie and serves as a consultant or advisory board member for Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), AbbVie, Rigel, Servier, Syndax, Astellas, and COTA Healthcare. J. Othman receives honoraria from Astellas, Pfizer, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. J. O’Nions receives honoraria from Johnson and Johnson, Servier, AbbVie, and Jazz; receives speakers fees from Astellas and Jazz; and serves as a consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie. C.M. serves on the advisory board for Syndax Pharmaceuticals; and serves on the safety monitoring committee for Kura Oncology. R.S. serves as a consultant for AbbVie, Rigel, and COTA Healthcare. J.N.S. receives research funding from Ikena; and serves as a consultant or advisory board member for Rigel and Sanofi. J.W.T. receives research funding from Acerta, Agios, Aptose, Array, AstraZeneca, Constellation, Genentech, Gilead, Incyte, Janssen, Kronos, Meryx, Petra, Schrodinger, Seattle Genetics, Syros, Takeda, and Tolero; and serves on the advisory board for Recludix Pharma. R.D. receives research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Jazz, and Pfizer; and serves as a consultant or advisory board member for Astellas, AbbVie, Jazz, Pfizer, and Servier. J.F.Z. receives research funding from AbbVie, AROG Pharmaceuticals, Astex, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Jazz, Loxo, Merck, Newave, Novartis, Sellas, Shattuck Labs, Stemline Therapeutics, Sumitomo Dainippon, Takeda, and Zentalis Pharmaceuticals; and serves as a consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie, Daiichi Sankyo, Foghorn, Gilead, Novartis, Sellas, Servier, Shattuck Labs, Sumitomo Dainippon, and Syndax. D.A.P. receives research funding from BMS, AbbVie, Karyopharm, and Teva; and serves as a consultant or advisory board member for Karyopharm, MEI, OncoVerity, Rigel, AbbVie, Syndax, Qihan, BMS, Sanofi, BeiGene, Ryvu Therapeutics, Servier, and Astellas. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Curtis A. Lachowiez, Division of Hematology/Medical Oncology, Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd, Portland, OR 97239; email: lachowie@ohsu.edu.

References

Author notes

C.A.L. and V.I.R. contributed equally to this study.

Data sharing requests of the primary included patient cohort can be directed to the corresponding author, Curtis Lachowiez (lachowie@ohsu.edu).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal