In this issue of Blood, Aoyama et al1 have identified using an animal model that selenoprotein deficiency disrupts redox homeostasis, leading to lipid peroxidation, impaired hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal, and a specific vulnerability in B-cell maturation, mirroring key features of aging-associated hematopoietic decline.

Hematopoiesis relies on the tightly regulated function of HSCs to maintain the production of both myeloid and lymphoid lineages. However, this intricate balance is lost as we age, such that lymphopoiesis declines with the emergence of myeloid dominance, leading to weakened immune function and heightened susceptibility to infections and hematologic malignancies.2 A key driver of these changes is the progressive dysregulation of the redox state in aging HSCs. Elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) disrupt HSC quiescence, leading to exhaustion, reduced regenerative capacity, and skewed lineage differentiation.3,4 In addition, Zhao et al5 identified ferroptosis, a lipid peroxidation-driven cell death pathway, as a significant contributor to HSC depletion under oxidative conditions. Aoyama et al advance our understanding of aging by identifying selenoproteins as critical antioxidant molecules that protect HSCs from lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, thereby preserving hematopoietic function and promoting resilience against aging-related oxidative stress.

Selenoproteins represent a family of selenium-containing enzymes that maintain redox homeostasis by neutralizing ROS and lipid peroxides.6 Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) is one such selenoprotein and reduces lipid hydroperoxides to alcohols using glutathione. This reaction halts the propagation of lipid peroxidation, a chain reaction initiated by free radicals attacking polyunsaturated fatty acids in membrane phospholipids (PUFA-PLs), ultimately protecting cells from ferroptosis. Thioredoxin reductases, another class of selenoproteins, regenerate thioredoxin, a molecule critical for repairing oxidized proteins. Together, these selenoproteins use nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate in redox cycling to mitigate oxidative stress, repair biomolecules, and halt lipid peroxidation cascades. Interestingly, this study was initiated after the authors identified a decline in antioxidant selenoprotein messenger RNA expression in aged human HSCs. To investigate this phenomenon, the authors employed a time-dependent deletion of n-TUtca2 (Tsrp) using the Cre-loxP system to disrupt selenoprotein synthesis to explore the molecular mechanisms driving these phenotypes. Transcriptomic profiling of HSCs and progenitor cells in Trsp−/− mice revealed a downregulation of selenoprotein-related genes, activation of oxidative stress pathways, and the upregulation of aging-associated transcriptional programs, effectively mimicking the loss of antioxidant defenses seen in aged hematopoietic systems.

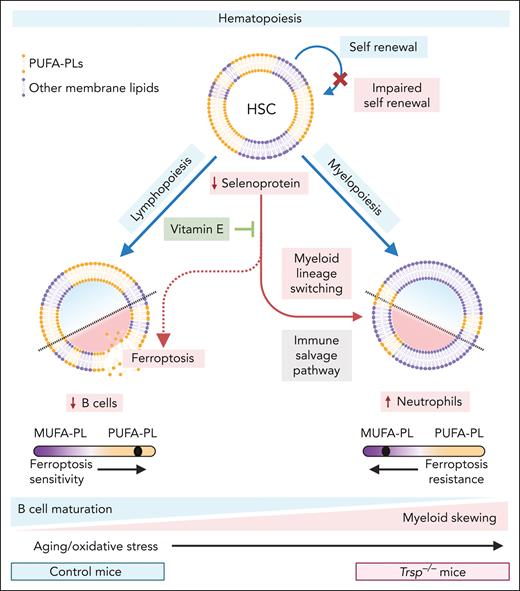

In this mouse model, the authors identified a marked reduction in functional HSCs, accompanied by a significant decline in their long-term repopulating ability, as demonstrated through competitive transplantation assays (see figure). The activation of oxidative stress pathways and aging-associated transcriptional programs in HSCs and progenitor cells further suggests the impairment of HSC quiescence and regenerative capacity. Additionally, the authors observed defective immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and lineage plasticity in Trsp−/− mice, with evidence pointing to a potential B-to-myeloid cell switch under oxidative stress (see figure).

Trsp−/− mice mimic aged hematopoiesis with impaired HSC function and B-cell development, accompanied with enhanced myeloid skewing. Balanced hematopoiesis (blue lines) involves (1) the self-renewal of HSCs and (2) the differentiation of HSCs into lymphoid cells (eg, B and T cells via lymphopoiesis) and myeloid cells (eg, neutrophils and monocytes via myelopoiesis). During aging, increased oxidative stress reduces HSC regenerative capacity and skews lineage differentiation toward myelopoiesis. Similarly, Trsp−/− mice, with impaired selenoprotein synthesis (red lines), exhibit reduced HSC self-renewal and a blockade in B-cell maturation, where pro-B cells differentiate toward the myeloid lineage (namely neutrophils). Additionally, heightened oxidative stress promotes ferroptosis in B cells, which are inherently susceptible due to elevated levels of PUFA-PLs, whereas myeloid cells, with lower PUFA-PL levels, are relatively protected. This phenotype, mimicking aged hematopoiesis, can be partially reversed by the ferroptosis inhibitor vitamin E, which restores redox balance and prevents cell death. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Trsp−/− mice mimic aged hematopoiesis with impaired HSC function and B-cell development, accompanied with enhanced myeloid skewing. Balanced hematopoiesis (blue lines) involves (1) the self-renewal of HSCs and (2) the differentiation of HSCs into lymphoid cells (eg, B and T cells via lymphopoiesis) and myeloid cells (eg, neutrophils and monocytes via myelopoiesis). During aging, increased oxidative stress reduces HSC regenerative capacity and skews lineage differentiation toward myelopoiesis. Similarly, Trsp−/− mice, with impaired selenoprotein synthesis (red lines), exhibit reduced HSC self-renewal and a blockade in B-cell maturation, where pro-B cells differentiate toward the myeloid lineage (namely neutrophils). Additionally, heightened oxidative stress promotes ferroptosis in B cells, which are inherently susceptible due to elevated levels of PUFA-PLs, whereas myeloid cells, with lower PUFA-PL levels, are relatively protected. This phenotype, mimicking aged hematopoiesis, can be partially reversed by the ferroptosis inhibitor vitamin E, which restores redox balance and prevents cell death. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Certain mature B-cell subtypes predominately rely on GPX4 for survival in oxidative environments.7,8 Selenoprotein deficiency exacerbates these vulnerabilities, impairing early B-cell differentiation and predisposing cells to lineage plasticity, which may lead to myeloid bias. Although the study highlights the critical role of selenoproteins in B-cell linage, it also raises important questions about lineage-specific effects. The pronounced vulnerability of B cells to selenoprotein deficiency contrasts with the relative resilience of myeloid cells. We have recently shown that in mature immune cells this disparity is driven by differences in lipid composition.8 Lymphoid cells are inherently enriched in PUFA-PLs, rendering them more prone to ferroptosis when GPX4 was inhibited. In contrast, myeloid cells possess lower PUFA-PL levels, which are programmed during their development, conferring greater resistance to oxidative stress and ferroptotic cell death.8 This poses the question, is the plasticity of B-cell development and switching to myeloid cells under oxidative stress linked with lipid metabolism and cellular lipid composition? Would this rewiring of B-cell development to myeloid cells limit the abundance of PUFA-PL in the cell membrane, protecting from ferroptosis? We suggest this is an “immune salvage” pathway, allowing for their survival as a ferroptosis-resistant innate immune cells (as opposed to just dying; see figure). This divergence in the cellular lipidome emphasizes the need to better understand lineage-specific adaptations to oxidative stress and suggests potential avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions that leverage these differences.

The therapeutic implications of these findings are significant. By demonstrating that vitamin E, a potent ferroptosis inhibitor, can partially restore HSC function and B-cell lineage commitment in Trsp−/− mice (see figure), the authors pave the way for redox-based interventions in hematopoietic aging. Tothova et al4 similarly showed that targeting ROS in aged HSCs can reverse myeloid skewing and restore regenerative potential, supporting strategies to mitigate immune decline. Aoyama et al highlight ferroptosis as a key driver of aging-related hematopoietic dysfunction and identify selenoproteins as critical to maintaining immune health, revealing a pathway that could preserve immune health in older adults, particularly in the context of immune senescence and hematologic malignancies. However, the nonphysiological nature of the Trsp−/− model may exaggerate certain phenotypes, necessitating validation in human HSCs or patient-derived models. Exploring the long-term efficacy of antioxidant therapies like vitamin E is essential to assess their clinical potential, particularly in specific patient cohorts.

In conclusion, this sophisticated work of Aoyama et al deepens our understanding of the intricate roles selenoproteins play in hematopoietic health and aging. Beyond their well-established antioxidant functions, selenoproteins emerge as critical mediators of lineage fidelity and HSC regeneration. This study not only elucidates how redox imbalance disrupts B-cell development and shifts lineage trajectories but also raises broader questions about the adaptability of hematopoietic systems under stress. Could the vulnerabilities exposed by selenoprotein deficiency reveal evolutionary trade-offs between resilience and specialization in immune cell lineages? By linking ferroptosis to immune decline, this study underscores the therapeutic promise of targeting redox imbalances with precision interventions, such as ferroptosis inhibitors. We anticipate that this work will serve as a foundation for uncovering deeper connections between redox regulation, cell fate decisions, and aging, offering new avenues to preserve immune health across the lifespan.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal