In this issue of Blood, Koh et al report a novel mechanism of lenalidomide resistance in myeloma.1 The authors found that resistance may be driven by an RNA editing enzyme, ADAR1, which regulates the cell death-promoting unedited double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) induced by lenalidomide treatment.

The immunomodulatory drug (IMiD) lenalidomide and its analogues alter substrate recognition of the E3 ligase substrate adapter protein cereblon, leading to degradation of myeloma-essential transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3. IMiDs are a mainstay of treatment in myeloma, combined with a range of standard and novel therapies, at all disease stages. However, eventual emergence of resistance is inevitable.

With the increasing choice and flexibility of myeloma treatments available, including IMiD derivatives cereblon E3 ligase modulatory drugs (CELMoDs) currently in trial, clinically deployable predictors and biomarkers of resistance to any drug or class of drugs enable better precision in therapy ordering and combinations. Thus, understanding what determines drug efficacy remains a highly pertinent clinical question.

Genetic variation in the IMiD binding protein cereblon has been reported but does not explain all drug resistance.2 Likewise, it has been demonstrated that rewiring of the transcriptional regulation of downstream IMiD targets IRF4 and MYC can bypass myeloma cell dependency on IMiD-target transcription factors and can drive resistance to IMiDs.3 However, in large genetically defined patient datasets, gain/amp chromosome 1q21 and loss of TP53 remain the strongest predicators of IMiD resistance.4 In the case of 1q21, the reason for this has remained unclear. Alongside other well-described myeloma disease drivers, ADAR1 is located in this frequently gained region of 1q21. These myelomas have higher ADAR1 levels and ADAR1-mediated editing of their transcriptome, but ADAR1 expression alone is also an independent predictor of survival.5 It has also been previously noted that ADAR1 overexpression promotes IMiD resistance in vitro.6

As a gatekeeper of viral RNA sensing by the innate immune system, ADAR1 recognizes nonviral dsRNA molecules and deaminates adenosine to inosine (A-to-I editing). This editing marks endogenous RNAs as “self,” thus preventing innate immune activation that would otherwise occur due to the sensing of high unedited dsRNA levels (see figure). Viral dsRNAs, on the other hand, remain unedited and are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as RIG-I and MDA5. A signaling cascade is initiated, ending with the expression of type I interferon (IFN) and hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) that possess proinflammatory, antiviral activity.

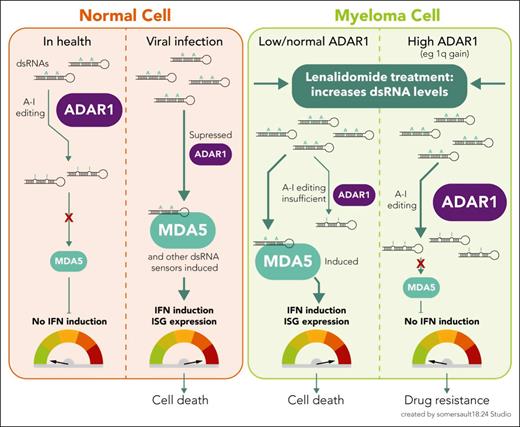

The role of ADAR1 in modulating type I IFN responses to cellular dsRNA in health and disease. In healthy cells, ADAR1 prevents inappropriate recognition of self dsRNAs as foreign, by A-to-I editing of dsRNA, thus suppressing type I IFN induction, which might otherwise cause autoimmune inflammation. In contrast, as part of the innate immune response to virus-infected cells, high levels of unedited viral dsRNA are sensed by PRRs (eg, MDA5, among others), which induces a type I IFN response, a cascade of ISG transcription, and an antiviral state. In myeloma cells, baseline ADAR1 levels vary. On lenalidomide treatment, levels of cytoplasmic dsRNA rise. As with a virus-infected cell, this dsRNA has the potential to be sensed by MDA5 and induce a type I IFN response, contributing to lenalidomide-induced cell death. However, in high-ADAR1-expressing myeloma cells, A-to-I editing reduces the burden of dsRNA that can be sensed by MDA5, dampening the dsRNA-sensing response and preventing IFN induction, thus contributing to lenalidomide resistance.

The role of ADAR1 in modulating type I IFN responses to cellular dsRNA in health and disease. In healthy cells, ADAR1 prevents inappropriate recognition of self dsRNAs as foreign, by A-to-I editing of dsRNA, thus suppressing type I IFN induction, which might otherwise cause autoimmune inflammation. In contrast, as part of the innate immune response to virus-infected cells, high levels of unedited viral dsRNA are sensed by PRRs (eg, MDA5, among others), which induces a type I IFN response, a cascade of ISG transcription, and an antiviral state. In myeloma cells, baseline ADAR1 levels vary. On lenalidomide treatment, levels of cytoplasmic dsRNA rise. As with a virus-infected cell, this dsRNA has the potential to be sensed by MDA5 and induce a type I IFN response, contributing to lenalidomide-induced cell death. However, in high-ADAR1-expressing myeloma cells, A-to-I editing reduces the burden of dsRNA that can be sensed by MDA5, dampening the dsRNA-sensing response and preventing IFN induction, thus contributing to lenalidomide resistance.

Dysregulation of A-to-I dsRNA editing is a current focus in immunity and cancer research. For example, genetic variants associated with changes in editing levels are highly enriched in genome-wide association study signals for common autoimmune and inflammatory diseases: risk variants that reduce editing can lead to increased IFN and ISG expression, suggesting inflammation may be driven by insufficient editing.7 Of particular relevance to the lenalidomide story, ADAR1 levels in cancer cells determine response to checkpoint blockade therapies. ADAR1 edits and represses endogenous retro-element-derived dsRNAs in some cancer cells, which otherwise trigger IFN-dependent antitumor responses,8 and loss of ADAR1 function boosts this response and sensitizes tumors to immunotherapy.9

Koh et al’s work brings together findings in broader immunology and cancer research with their previous observation of high ADAR1 levels in high-risk myelomas such as those with gain/amp 1q21, specifically to examine how lenalidomide responses may depend on dsRNA sensing machinery. First, they show that ADAR1 expression correlates inversely with lenalidomide responses in the CoMMpass dataset of gene expression in newly diagnosed myeloma samples. Using knockdown, overexpression, and RNA editing-defective ADAR1 mutant approaches, they demonstrate in lenalidomide-sensitive and -resistant myeloma cell lines that lenalidomide resistance can be driven by ADAR1 p150 isoform activity and that its dsRNA editing activity is required to increase lenalidomide resistance. Second, the sensing of high unedited dsRNA levels in myeloma cells, which leads to type I IFN response-mediated myeloma cell death, depends upon MDA5 as opposed to other PRRs RIG-I and PKR. Without MDA5 activity, even minimal ADAR1 dsRNA editing does not lead to cell death.

To summarize, Koh et al propose that high-ADAR1-associated lenalidomide resistance results from more dsRNA editing, leading to lower sensing of dsRNA and therefore a blunted IFN response (see figure). In myeloma xenograft models treated with lenalidomide, ADAR1 knockdown reduced tumor growth but MDA5 knockdown increased it, driving resistance to lenalidomide. Although specific ADAR1 inhibitors in development are not yet generally available, 8-azaadenosine, previously demonstrated to reduce ADAR1 expression, enhanced xenograft myeloma killing on combination with lenalidomide.

Two key questions are discussed but not fully answered in this work: first, how does lenalidomide activate dsRNA sensing machinery? Evidence is presented that it may be by increasing levels of dsRNA in the cell. Data elsewhere suggest that aberrantly transcribed, immunogenic endogenous retroelement-derived dsRNAs in cancer cells can be boosted by epigenetic therapies.10 Might IMiDs have similar effects?

Second, how do observations made in this work integrate with the accepted mechanisms by which IMiDs kill myeloma cells (the downregulation of myeloma-essential transcription factors IRF4 and MYC following canonical IKZF1/3 degradation)? Is the effect on dsRNA levels downstream of, or parallel to, IRF4 and MYC effects, and how does it sit alongside recently described resistance mechanisms involving their transcriptional rewiring? Does myeloma cell IFN induction mediate any of lenalidomide’s effects on the tumor microenvironment?

There is interest in developing ADAR1 inhibitors to enhance activity of or reverse resistance to checkpoint blockade more widely in oncology. Do these data mean that we can add IMiDs to the list of immunotherapies whose efficacy may be enhanced by ADAR1 inhibition? This may well be the case, but corroborative work is required. Increasingly, myeloma therapeutics shift their focus to manipulation of the immune system’s control of the cancer; where IMiDs first ventured, other approaches have followed. As T-cell-redirecting and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies become a mainstay of treatment, another pathway by which their activity may be optimized will no doubt be carefully examined.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.G. declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal