Key Points

Lenalidomide induces immunomodulating responses through the activation of dsRNA-sensing pathway.

ADAR1 drives lenalidomide resistance in MM via the suppression of lenalidomide-induced dsRNA-sensingresponse.

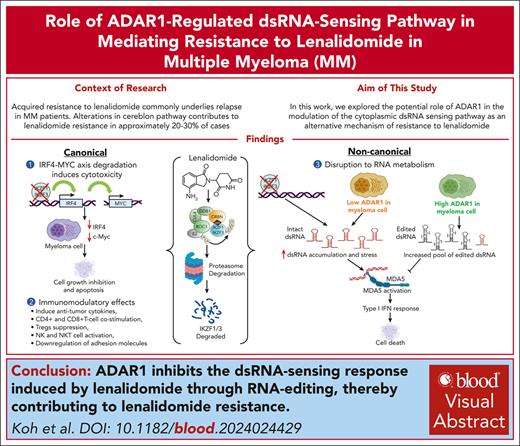

Visual Abstract

Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) are a major class of drugs for treating multiple myeloma (MM); however, acquired resistance to IMiDs remains a significant clinical challenge. Although alterations in cereblon and its pathway are known to contribute to IMiD resistance, they account for only 20% to 30% of cases, and the underlying mechanisms in the majority of the resistance cases remain unclear. Here, we identified adenosine deaminase acting on RNA1 (ADAR1) as a novel driver of lenalidomide resistance in MM. We showed that lenalidomide activates the MDA5-mediated double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)–sensing pathway in MM cells, leading to interferon (IFN)-mediated apoptosis, with ADAR1 as the key regulator. Mechanistically, ADAR1 loss increased lenalidomide sensitivity through endogenous dsRNA accumulation, which in turn triggered dsRNA-sensing pathways and enhanced IFN responses. Conversely, ADAR1 overexpression reduced lenalidomide sensitivity, attributed to increased RNA editing frequency, reduced dsRNA accumulation, and suppression of the dsRNA-sensing pathways. In summary, we report the involvement of ADAR1-regulated dsRNA sensing in modulating lenalidomide sensitivity in MM. These findings highlight a novel RNA-related mechanism underlying lenalidomide resistance and underscore the potential of targeting ADAR1 as a novel therapeutic strategy.

Introduction

Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) are the current standard-of-care treatment for multiple myeloma (MM) and have shown profound clinical efficacy.1,2 However, acquired resistance to IMiDs commonly underlies relapse.3,4 IMiDs bind directly to cereblon (CRBN), the substrate adaptor of the CRL4CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase, and promote the proteasomal degradation of Ikaros (IKZF1) and Aiolos (IKZF3), resulting in the direct inhibition of MM cell growth and stimulation of immunomodulatory effects.5,6 Although resistance to IMiD is often linked to genetic defects in CRBN pathway genes and the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, these abnormalities are only present in 20% to 30% IMiD-refractory cases.7-11 Emerging research is beginning to uncover CRBN-independent mechanisms of IMiD resistance, including aberrant oncogenic signaling, epigenetic alterations, transcription factor plasticity, dysregulated cell surface expression, changes in the tumor microenvironment, and immune escape mechanisms.8,12-21

Moreover, specific molecular abnormalities such as gain/amplification of 1q (gain/amp1q), deletion of 17p (del17p), and double-hit events may also contribute to therapeutic resistance.22,23 A recent genomic analysis has identified gain/amp1q as one of the most frequent cytogenetic abnormalities in IMiD-refractory patients with MM.24 Notably, the ADAR1 gene, which encodes an adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing enzyme, is located in the amplified chromosomal region-1q21.25,26 RNA editing, a form of posttranscription modification of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), is a key physiological process involved in transcriptomic and proteomic diversity.27 Aberrant ADAR1-mediated RNA editing has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several human malignancies, including MM.25,26,28,29

ADAR1 exists as 2 distinct isoforms: the constitutively expressed p110 that is localized in the nucleus; and the interferon (IFN)-inducible p150 that is predominantly cytoplasmic.30 Recent studies have shown that ADAR1 promotes resistance to cancer therapies by modulating the innate immune response through endogenous dsRNA.31-33 Accumulation of cytoplasmic dsRNA activates the dsRNA-sensing pathways, leading to the induction of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) and increased IFN production. ADAR1, particularly the p150 isoform, attenuates this immune response by editing dsRNA, thus inhibiting the dsRNA-sensing pathways (supplemental Information, available on the Blood website).27,34-39

Importantly, in our previous study, we reported a close association between high ADAR1 expression and hyperedited MM transcriptome with reduced responsiveness of patients with MM to IMiDs.25 We therefore hypothesize that ADAR1 and RNA editing may be involved in IMiD resistance. Our current work aims to interrogate the mechanism by which aberrant ADAR1 activity regulates IMiD sensitivity in MM. Here, we report an understudied immunotherapeutic role of lenalidomide that works through triggering the tumor-intrinsic dsRNA-sensing pathway in MM, and we identify the ADAR1-mediated suppression of the immunogenic dsRNA response as a novel mechanism regulating lenalidomide resistance.

Methods

Public data set analysis

Generation of LenR MM cell lines

Isogenic lenalidomide-resistant (LenR) KMS-11 and MM1.S cells were established in the presence of escalating doses of lenalidomide over an extended period. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed to examine for genetic alterations in LenR cells.

In vitro and in vivo studies

Lentivirus was used to establish stable isogenic cell lines with ADAR1 knockdown (KD) and ADAR1 overexpression (OE) or dsRNA sensor-specific KD or MDA5 OE. Small interfering RNAs were used to knock down IKZF1 and IKZF3. Functional assays (cell viability, colony formation, cell-cycle, and apoptosis assays) were performed; messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein expression were determined with quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, western blot, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; and cellular RNA content was assessed with immunofluorescence and dsRNA dot blot. Four- to 5-week-old female NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory for in vivo studies.

Detailed methods are described in the supplemental Information.

Results

Acquired IMiD resistance could involve mechanisms beyond CRBN pathway abnormalities in MM

To delineate the canonical mechanism of IMiD resistance, we first analyzed the CoMMpass data set, focusing on CRBN pathway genes (supplemental Table 1). Our analysis on gene expression, mutations, and copy number aberrations for CRBN pathway genes showed only minimal to modest correlations with patient responses to IMiD-based treatments (supplemental Figure 1A-D), consistent with previous studies.7-11 To further investigate the alternative mechanisms underlying IMiD resistance, we generated isogenic LenR cell line models in KMS-11 and MM1.S (supplemental Figure 2A-B), which were the two most sensitive cell lines among the 10 MM cell lines we tested (supplemental Figure 2C). Functional characterization of these LenR cell lines demonstrated increased cell proliferation (supplemental Figure 2D-E) and enhanced colony-formation ability (supplemental Figure 2F) compared with their drug-sensitive parental cells (LenS), indicating a more proliferative and aggressive nature. WES of the LenR cells revealed no significant genomic alterations, including in CRBN pathway genes (supplemental Figure 2G-H), suggesting that acquired lenalidomide resistance may be driven by nongenomic events and mechanisms beyond the CRBN pathway.

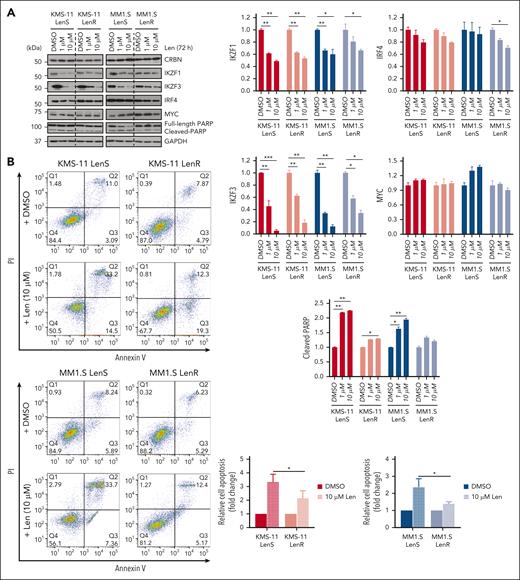

Despite reduced sensitivity to lenalidomide in the LenR cells, as shown by the cleaved PARP and annexin V assays (Figure 1A-B), lenalidomide-induced degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 and their downstream target IRF4 remained effective, albeit less pronounced in LenR compared with LenS cells (Figure 1A). These findings further support that lenalidomide resistance may involve mechanisms beyond the CRBN-IKZF1/IKZF3 degradation pathway.

High ADAR1 expression is associated with resistance to IMiDs. (A) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for the effect of lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) on CRBN, IKZF1/3, IRF4, MYC, and PARP in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells after 72 hours of treatment (left). The bar graphs (right) summarize the levels of IKZF1, IKZF3, IRF4, MYC, and cleaved-PARP, normalized to GAPDH, with quantification performed using ImageJ. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells treated with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 6 days. Representative apoptosis plots and quantification, based on annexin V/Propidium Iodide (PI) staining, are shown. (C) Volcano plot showing the correlation between protein expression levels and responses to lenalidomide in hematopoietic and lymphoid cancer tissues (n = 58), including MM cell lines from the MD Anderson Cancer Center cell lines project dataset. The horizontal line represents the significance threshold at P = 0.05 level. (D) Expression levels of ADAR1 and CRBN in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells validated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) (left) and western blot (right). Blot with ADAR1 p150 and ADAR1 p110 was probed with ab88574 (Abcam) and the blot with only ADAR1 p150 was immunoblotted with ab126745 (Abcam). (E) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with MM with high vs low ADAR1 expression who received either lenalidomide-based (n = 927) or pomalidomide-based (n = 239) treatments from the CoMMpass study (IA21 release). Survival curves were generated by splitting patients into top 40% and bottom 40% groups based on ADAR1 expression values. Survival analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazard method with the log2-transformed gene expression profile, where the hazard ratio (HR), confidence interval, and P values were indicated. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of biological triplicates. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001 as determined by two-tailed Student t-test. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; Len, lenalidomide; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

High ADAR1 expression is associated with resistance to IMiDs. (A) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for the effect of lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) on CRBN, IKZF1/3, IRF4, MYC, and PARP in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells after 72 hours of treatment (left). The bar graphs (right) summarize the levels of IKZF1, IKZF3, IRF4, MYC, and cleaved-PARP, normalized to GAPDH, with quantification performed using ImageJ. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells treated with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 6 days. Representative apoptosis plots and quantification, based on annexin V/Propidium Iodide (PI) staining, are shown. (C) Volcano plot showing the correlation between protein expression levels and responses to lenalidomide in hematopoietic and lymphoid cancer tissues (n = 58), including MM cell lines from the MD Anderson Cancer Center cell lines project dataset. The horizontal line represents the significance threshold at P = 0.05 level. (D) Expression levels of ADAR1 and CRBN in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells validated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) (left) and western blot (right). Blot with ADAR1 p150 and ADAR1 p110 was probed with ab88574 (Abcam) and the blot with only ADAR1 p150 was immunoblotted with ab126745 (Abcam). (E) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with MM with high vs low ADAR1 expression who received either lenalidomide-based (n = 927) or pomalidomide-based (n = 239) treatments from the CoMMpass study (IA21 release). Survival curves were generated by splitting patients into top 40% and bottom 40% groups based on ADAR1 expression values. Survival analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazard method with the log2-transformed gene expression profile, where the hazard ratio (HR), confidence interval, and P values were indicated. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of biological triplicates. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001 as determined by two-tailed Student t-test. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; Len, lenalidomide; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

ADAR1 expression is upregulated in IMiD-resistant MM cells and correlates with poor survival

We therefore proceeded to elucidate whether ADAR1 is involved in one of the non-canonical mechanisms of IMiD resistance. Consistent with our previous findings that poor IMiD patient responders exhibit higher ADAR1 expression,25 we observed that MM cell lines with higher ADAR1 protein levels showed reduced sensitivity to lenalidomide (supplemental Figure 2I). This finding aligns with observations from the proteomics-based study by MD Anderson Cancer Center,40,41 which also demonstrated that cell lines with high ADAR1 protein expression were more resistant to lenalidomide (Figure 1C). In contrast, CRBN expression did not show a correlation (supplemental Figure 2I), and there were no baseline mutations in the CRBN pathway genes in these 10 cell lines, except for KMS-34, according to the Cancer Dependency Map and Keats lab resources (supplemental Table 2). Furthermore, ADAR1 was also not mutated in MM (supplemental Table 3), and our WES data indicated no genetic alterations in ADAR1 in LenR cells, confirming that differential lenalidomide sensitivity in MM was not associated with genetic alterations in CRBN pathway genes or ADAR1.

In both MM1.S and KMS-11 LenR cells, CRBN expression was reduced, which is not unexpected,8,11 but more importantly, ADAR1 was concordantly upregulated at both the mRNA and protein levels, specifically the p150 isoform (Figure 1D). Analysis of ADAR1 levels in relation to survival outcomes in IMiD-treated patients from the CoMMpass study revealed a significant association between higher ADAR1 expression and poorer survival (Figure 1E). These, collectively, suggest that ADAR1 may play a role in mediating lenalidomide resistance.

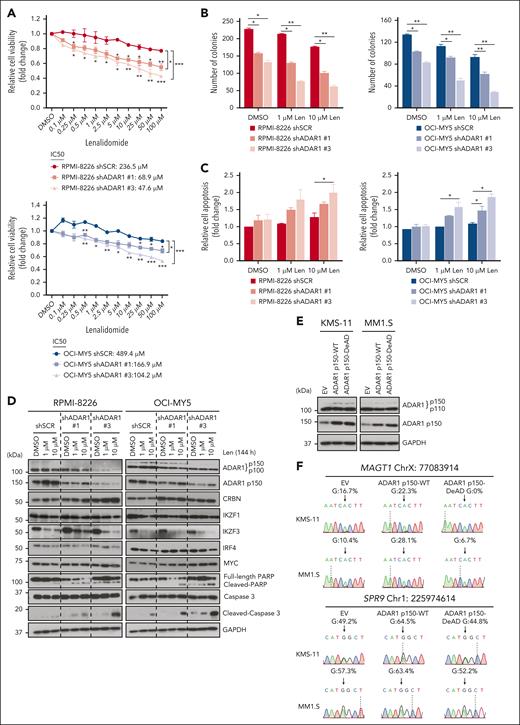

ADAR1 impairs IMiD sensitivity in MM cells in an RNA editing–dependent manner

To investigate the direct role of ADAR1 in IMiD resistance, we knocked down ADAR1 in two LenR cell lines, RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 (supplemental Figure 3A). ADAR1 KD led to increased sensitivity to lenalidomide, as shown by a significant reduction in cell viability and lower 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) (Figure 2A), decreased colony formation in methylcellulose (Figure 2B), and enhanced apoptosis, indicated by higher annexin V positivity and increased cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 2C-D). Importantly, ADAR1 KD did not significantly alter lenalidomide-induced degradation of IKZF1, IKZF3, and IRF4 (Figure 2D), suggesting that ADAR1 affects lenalidomide sensitivity independently of the CRBN-IKZF1/IKZF3 degradation pathway.

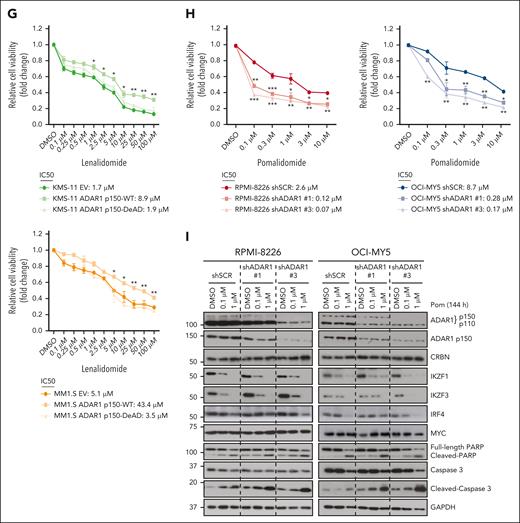

ADAR1 reduces IMiD sensitivity in MM cells in an RNA editing–dependent manner. (A) Cell viability of ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CellTiter-Glo (CTG) assay. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were computed with CompuSyn following Chou-Talalay method. (B) Colony formation assay of ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells in methylcellulose-based media, treated with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) over 14 days. (C) Apoptosis analysis in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells treated with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) for 6 days, detected using annexin V/PI staining by flow cytometry. (D) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for the effect of lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) on the total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), CRBN, IKZF1/3, IRF4, MYC, PARP, and cleaved caspase-3 from ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after 144 hours (6 days) of treatment. (E) Western blot validation of the OE of ADAR1 p150 WT (ADAR1 p150-WT) or ADAR1 p150 catalytic DeAD mutant (ADAR1 p150-DeAD) in KMS-11 and MM1.S cells. Blot with ADAR1 p150 and ADAR1 p110 was probed with ab88574 (Abcam) and the blot with only ADAR1 p150 was immunoblotted with ab126745 (Abcam). (F) Sanger sequencing chromatograms illustrating the RNA editing levels of ADAR1 target genes (MAGT1 and SRP9) in KMS-11 and MM1.S cells in response to ADAR1 p150 OE (EV, ADAR1 p150-WT, and ADAR1 p150-DeAD). Percentages denote the editing frequencies of the corresponding editing site indicated by the arrow. (G) Cell viability of ADAR1 p150-overexpressed KMS-11 and MM1.S cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CTG assay. The IC50 values were computed with CompuSyn following Chou-Talalay method. (H) Cell viability of ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of pomalidomide, determined by CTG assay. The IC50 values were computed with CompuSyn following Chou-Talalay method. (I) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for the effect of pomalidomide (0.1 or 1 μM) on the total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), CRBN, IKZF1/3, MYC, PARP, and cleaved caspase-3 from ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after 144 hours (6 days) of treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Significance differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test and for the line bracket by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001. DeAD, catalytic deaminase domain mutant; EV, empty vector; Pom, pomalidomide; WT, wild-type.

ADAR1 reduces IMiD sensitivity in MM cells in an RNA editing–dependent manner. (A) Cell viability of ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CellTiter-Glo (CTG) assay. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were computed with CompuSyn following Chou-Talalay method. (B) Colony formation assay of ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells in methylcellulose-based media, treated with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) over 14 days. (C) Apoptosis analysis in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells treated with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) for 6 days, detected using annexin V/PI staining by flow cytometry. (D) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for the effect of lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) on the total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), CRBN, IKZF1/3, IRF4, MYC, PARP, and cleaved caspase-3 from ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after 144 hours (6 days) of treatment. (E) Western blot validation of the OE of ADAR1 p150 WT (ADAR1 p150-WT) or ADAR1 p150 catalytic DeAD mutant (ADAR1 p150-DeAD) in KMS-11 and MM1.S cells. Blot with ADAR1 p150 and ADAR1 p110 was probed with ab88574 (Abcam) and the blot with only ADAR1 p150 was immunoblotted with ab126745 (Abcam). (F) Sanger sequencing chromatograms illustrating the RNA editing levels of ADAR1 target genes (MAGT1 and SRP9) in KMS-11 and MM1.S cells in response to ADAR1 p150 OE (EV, ADAR1 p150-WT, and ADAR1 p150-DeAD). Percentages denote the editing frequencies of the corresponding editing site indicated by the arrow. (G) Cell viability of ADAR1 p150-overexpressed KMS-11 and MM1.S cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CTG assay. The IC50 values were computed with CompuSyn following Chou-Talalay method. (H) Cell viability of ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of pomalidomide, determined by CTG assay. The IC50 values were computed with CompuSyn following Chou-Talalay method. (I) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for the effect of pomalidomide (0.1 or 1 μM) on the total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), CRBN, IKZF1/3, MYC, PARP, and cleaved caspase-3 from ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after 144 hours (6 days) of treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Significance differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test and for the line bracket by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001. DeAD, catalytic deaminase domain mutant; EV, empty vector; Pom, pomalidomide; WT, wild-type.

To determine whether ADAR1’s effect on lenalidomide resistance is mediated through its RNA editing activity, we analyzed the A-to-I editing profiles of known ADAR1 targets (SRP9 and MAGT1) as a surrogate for its RNA editing activity. After ADAR1 KD, we verified that there was a site-specific decrease in A-to-I editing frequency (supplemental Figure 3B). To further support this, we established isogenic models in KMS-11 and MM1.S expressing either wild-type (WT) or catalytic deaminase domain (DeAD) mutant (defective RNA editing) p11042 and p150 isoforms of ADAR1 (Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 3D). OE of the WT-p110 or WT-p150 isoforms increased RNA editing activity, whereas their respective DeAD mutants did not (Figure 2F; supplemental Figure 3C).

If ADAR1’s RNA editing function is crucial for modulating lenalidomide resistance, then OE of the WT but not the DeAD mutant isoforms of ADAR1 should affect lenalidomide sensitivity. Indeed, OE of the WT-p150 and WT-p110 isoforms in KMS-11 and MM1.S cells led to decreased sensitivity to lenalidomide. Conversely, OE of the DeAD mutant isoforms did not render increased resistance to lenalidomide (Figure 2G; supplemental Figure 3E). These findings indicate that ADAR1’s role in lenalidomide sensitivity is, at least in part, dependent on its RNA editing function.

We extended our investigation to pomalidomide, a third-generation IMiD. ADAR1 KD also significantly increased sensitivity to pomalidomide (Figure 2H). Consistent with lenalidomide, ADAR1 KD minimally affected pomalidomide-induced degradation of IKZF1, IKZF3, and IRF4 (Figure 2I). Interestingly, LenR cells exhibited a threefold to fourfold increase in the IC50 for pomalidomide (supplemental Figure 3F), indicating some degree of cross-resistance despite pomalidomide’s higher potency.

We further assessed the effects of ADAR1 inhibition on sensitivity to other standard MM therapies. Although ADAR1 KD resulted in minimal to modest enhancement in sensitivity to bortezomib (supplemental Figure 3G), it did not affect sensitivity to dexamethasone (supplemental Figure 3H), suggesting that the effect of ADAR1 inhibition on MM drug sensitivity is more specific to IMiDs.

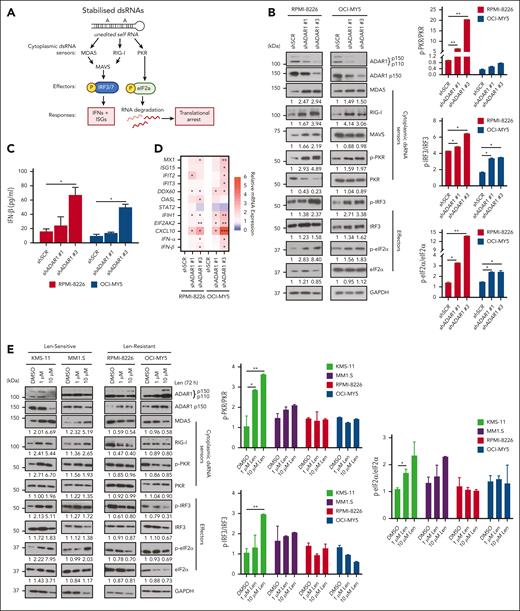

Lenalidomide activates the dsRNA-sensing pathways in MM cells, with ADAR1-p150 isoform playing a central role

ADAR1-mediated RNA editing is a key regulator of the physiological dsRNA response, which prevents the cytoplasmic RNA sensors of the innate immune system from aberrantly recognizing endogenous dsRNA as foreign.37 To determine whether the differential IMiD sensitivity conferred by ADAR1 is linked to its role in regulating dsRNA surveillance, we first determined, at the untreated physiological level, the connection between ADAR1 and key cytoplasmic dsRNA sensors, MDA5, RIG-I, and PKR (Figure 3A),27,37 in MM cells, which is largely unknown to date. KD of ADAR1 in RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells resulted in the upregulation of these dsRNA sensors and their downstream effectors, including phosphorylated IRF3 and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) (Figure 3B). This upregulation was accompanied by increased IFN-β protein secretion and elevated mRNA levels of IFNs and ISGs (Figure 3C-D), suggesting that dsRNA-sensing pathway activation enhances IFN activity and contributes to cellular cytotoxicity.

Lenalidomide induces dsRNA-sensing pathway and stimulates anti-MM intrinsic immunity in MM cells. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating the activation of the dsRNA sensor–mediated signaling pathways in cells. (B) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic cell lysates for total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), and the dsRNA sensor–mediated signaling in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells (left). The bar graphs (right) summarize p-PKR, p-IRF3, and p-eIF2α band intensities normalized to GAPDH and total protein content, quantified via ImageJ. Densitometry analyses for the relative protein expression normalized to GAPDH are displayed below the western blots. (C) Spontaneous IFN-β protein secretion by ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells in the culture supernatant, assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (D) Heat map showing the normalized mRNA expression of ISGs and IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells, determined by qRT-PCR. (E) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic-cell lysates for total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), and the dsRNA sensor–mediated signaling in lenalidomide-sensitive (Len-sensitive) KMS-11 and MM1.S cells vs LenR RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after treatment with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) for 72 hours (left). The bar graphs (right) summarize p-PKR, p-IRF3, and p-eIF2α band intensities normalized to GAPDH and total protein content, quantified via ImageJ. Densitometry analyses for the relative protein expression normalized to GAPDH are displayed below the western blots. (F) Histogram of GO enrichment analysis after lenalidomide treatment (10 μM) in MM1.S and OPM2 cells at 12 hours and 24 hours, respectively, relative to control (RNA-seq data GSE246435, FDR adjusted P value <0.05 and log2-fold >1.5). Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001, as determined by two-tailed Student t test. FDR, false discover rate; GO, gene ontology.

Lenalidomide induces dsRNA-sensing pathway and stimulates anti-MM intrinsic immunity in MM cells. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating the activation of the dsRNA sensor–mediated signaling pathways in cells. (B) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic cell lysates for total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), and the dsRNA sensor–mediated signaling in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells (left). The bar graphs (right) summarize p-PKR, p-IRF3, and p-eIF2α band intensities normalized to GAPDH and total protein content, quantified via ImageJ. Densitometry analyses for the relative protein expression normalized to GAPDH are displayed below the western blots. (C) Spontaneous IFN-β protein secretion by ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells in the culture supernatant, assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (D) Heat map showing the normalized mRNA expression of ISGs and IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells, determined by qRT-PCR. (E) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic-cell lysates for total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), and the dsRNA sensor–mediated signaling in lenalidomide-sensitive (Len-sensitive) KMS-11 and MM1.S cells vs LenR RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after treatment with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) for 72 hours (left). The bar graphs (right) summarize p-PKR, p-IRF3, and p-eIF2α band intensities normalized to GAPDH and total protein content, quantified via ImageJ. Densitometry analyses for the relative protein expression normalized to GAPDH are displayed below the western blots. (F) Histogram of GO enrichment analysis after lenalidomide treatment (10 μM) in MM1.S and OPM2 cells at 12 hours and 24 hours, respectively, relative to control (RNA-seq data GSE246435, FDR adjusted P value <0.05 and log2-fold >1.5). Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001, as determined by two-tailed Student t test. FDR, false discover rate; GO, gene ontology.

To identify which ADAR1 isoform, p110 or p150, regulates dsRNA-sensing pathways in MM, we introduced each isoform separately into the cells. The p150 isoform significantly reduced the levels of dsRNA-sensing proteins and their effectors (supplemental Figure 4A-B), as well as IFNs and ISGs (supplemental Figure 4C-F), whereas p110 isoform rendered little to no change in the phenotype. The WT-p150 isoform resulted in a more pronounced decrease in MDA5 and RIG-I levels, IFN-β protein secretion, and the mRNA expression of several ISGs and IFNs than the DeAD-p150 mutant. These findings indicate that ADAR1 regulates the dsRNA-sensing pathways through its RNA editing activity, with the p150 isoform playing a central role. Furthermore, lenalidomide treatment significantly increased ADAR1 expression, specifically the p150 isoform, in LenR lines RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 (Figure 3E), consistent with our observations in the isogenic LenR models (Figure 1D). Conversely, ADAR1 levels were reduced in lenalidomide-sensitive lines KMS-11 and MM1.S, suggesting a link between ADAR1 expression and lenalidomide efficacy.

We next investigated whether the lenalidomide’s immunomodulatory effects, which also involve IFN responses, are associated with dsRNA-sensing pathways. Treatment of lenalidomide-sensitive cell lines (KMS-11 and MM1.S) with lenalidomide led to the upregulation of MDA5, RIG-I, and PKR, alongside increased phosphorylation of IRF3 and eIF2α (Figure 3E). In contrast, resistant lines (RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5) showed minimal to no changes in these markers, indicating that the dsRNA-sensing pathways were less effective in the resistant cells and that an active dsRNA-sensing pathway may be important for lenalidomide sensitivity.

Additionally, analysis of publicly available RNA-seq data from lenalidomide- and pomalidomide-treated MM cells (GSE246435 and GSE243990)14,15 revealed that significantly downregulated genes were associated with translation and RNA processing, indicating disruptions in RNA metabolism that could lead to increased intracellular dsRNA. Conversely, upregulated genes were related to immune signaling, inflammatory response, and antiviral immune defense response (Figure 3F; supplemental Figure 4G), suggesting activation of the IFN pathway. Collectively, these findings suggest that lenalidomide’s mode of action may indeed be associated with dsRNA-sensing pathway activation, resulting in increased inflammatory IFN signaling. This also explains the mechanisms underlying enhanced sensitivity of ADAR1-KD MM cells to lenalidomide, as both perturbations activate dsRNA-sensing and IFN pathway responses.

ADAR1-mediated RNA editing suppresses lenalidomide-induced accumulation of cytoplasmic dsRNA in MM cells

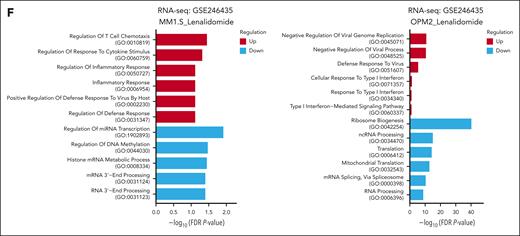

To further explore ADAR1 and lenalidomide-induced dsRNA-sensing responses in MM, we assessed cytoplasmic dsRNA levels with the dsRNA-specific J2 antibody,43 which detects intact, unedited RNA duplexes. Lenalidomide treatment rendered increased cytoplasmic dsRNA accumulation in the four MM cell lines tested but more significantly in lenalidomide-sensitive KMS-11 and MM1.S cells than LenR RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells (Figure 4A). To validate this observation, we replicated lenalidomide’s effects by knocking down IKZF1 and/or IKZF3 and stained for dsRNA. IKZF1 and/or IKZF3 KD similarly increased cytoplasmic dsRNA more pronouncedly in KMS-11 than RPMI-8226 cells (supplemental Figure 5A-B), suggesting that IMiDs induce dsRNA-sensing responses through dsRNA accumulation to mediate IFN responses for their immunomodulatory action. Concordantly, RNA-seq data from IKZF3 KD OPM2 cells (GSE246435)15 revealed that the significantly downregulated genes in shIKZF3 cells were related to cytoplasmic translation, whereas the upregulated genes were associated with inflammatory responses (supplemental Figure 5C).

ADAR1-mediated RNA editing inhibits lenalidomide-induced dsRNA-sensing responses in MM cells. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of cellular dsRNA with J2 antibody in Len-sensitive (KMS-11 and MM1.S cells) vs Len-resistant (RPMI-8226 cells and OCI-MY5) cells after treatment with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) for 72 hours (left). Orange-red fluorescence indicates dsRNA signals and blue fluorescence indicates DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining. Scale bars indicate 20 μm. Bar graph quantification of the relative mean cytoplasmic dsRNA fluorescence intensity (right). (B) Dot blot analysis of cellular dsRNA using dsRNA-specific J2 antibody in total RNA extracted from ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells blotted on Biodyne nylon membrane. RNA loading was verified by methylene blue staining. (C) Dot blot analysis of cellular dsRNA using dsRNA-specific J2 antibody in total RNA extracted from ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells blotted on Biodyne nylon membrane. As indicated, total RNA extracted were treated with RNase III for 30 minutes at 37°C as negative control for dsRNA signal. RNA loading was verified by methylene blue staining. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of cellular dsRNA with J2 antibody in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 cells after treatment with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 72 hours (left). Orange-red fluorescence indicates dsRNA signals, green fluorescence indicates ADAR1 p150 expression, and blue fluorescence indicates DAPI staining. Scale bars indicate 20 μm. Bar graph quantification of the relative mean cytoplasmic dsRNA fluorescence intensity (right). (E) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), and the dsRNA sensor–mediated signaling in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after treatment with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 72 hours (top). The bar graphs (bottom) summarize p-PKR, p-IRF3, and p-eIF2α band intensities normalized to GAPDH and total protein content, quantified via ImageJ. Densitometry analyses for the relative protein expression normalized to GAPDH are displayed below the western blots. (F) Induction of IFN-β protein secretion by ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after treatment with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) for 72 hours, assessed by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001, as determined by two-tailed Student t test.

ADAR1-mediated RNA editing inhibits lenalidomide-induced dsRNA-sensing responses in MM cells. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of cellular dsRNA with J2 antibody in Len-sensitive (KMS-11 and MM1.S cells) vs Len-resistant (RPMI-8226 cells and OCI-MY5) cells after treatment with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) for 72 hours (left). Orange-red fluorescence indicates dsRNA signals and blue fluorescence indicates DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining. Scale bars indicate 20 μm. Bar graph quantification of the relative mean cytoplasmic dsRNA fluorescence intensity (right). (B) Dot blot analysis of cellular dsRNA using dsRNA-specific J2 antibody in total RNA extracted from ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells blotted on Biodyne nylon membrane. RNA loading was verified by methylene blue staining. (C) Dot blot analysis of cellular dsRNA using dsRNA-specific J2 antibody in total RNA extracted from ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells blotted on Biodyne nylon membrane. As indicated, total RNA extracted were treated with RNase III for 30 minutes at 37°C as negative control for dsRNA signal. RNA loading was verified by methylene blue staining. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of cellular dsRNA with J2 antibody in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 cells after treatment with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 72 hours (left). Orange-red fluorescence indicates dsRNA signals, green fluorescence indicates ADAR1 p150 expression, and blue fluorescence indicates DAPI staining. Scale bars indicate 20 μm. Bar graph quantification of the relative mean cytoplasmic dsRNA fluorescence intensity (right). (E) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), and the dsRNA sensor–mediated signaling in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after treatment with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 72 hours (top). The bar graphs (bottom) summarize p-PKR, p-IRF3, and p-eIF2α band intensities normalized to GAPDH and total protein content, quantified via ImageJ. Densitometry analyses for the relative protein expression normalized to GAPDH are displayed below the western blots. (F) Induction of IFN-β protein secretion by ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells after treatment with lenalidomide (1 or 10 μM) for 72 hours, assessed by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001, as determined by two-tailed Student t test.

Importantly, ADAR1 depletion led to a marked increase in dsRNA levels in RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells (Figure 4B-C). This increase was specific to dsRNA, because treatment with RNase III (which degrades dsRNA) abolished the elevated dsRNA levels observed in ADAR1 KD cells (Figure 4C). Immunofluorescence further validated these findings (supplemental Figure 6A), demonstrating that ADAR1 regulates dsRNA-sensing responses by suppressing cytoplasmic dsRNA accumulation.

In ADAR1-KD cells treated with lenalidomide, we observed further dsRNA accumulation (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 6B). This was manifested alongside enhanced dsRNA-sensing protein profile (Figure 4E), increased IFN-β protein secretion (Figure 4F), and elevated mRNA expression of ISGs and IFNs (supplemental Figure 6C). Similar dsRNA-sensing responses were also observed with pomalidomide treatment in ADAR1-KD cells (supplemental Figure 7A-C).

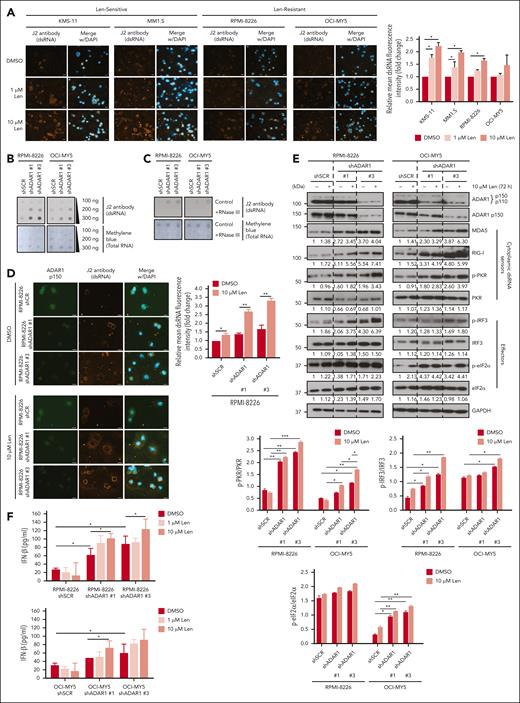

Conversely, LenR cells, which exhibit higher ADAR1 expression (Figure 1D), showed reduced dsRNA accumulation compared with LenS cells (Figure 5A). This reduction coincided with increased ADAR1-mediated editing activity, validating the RNA editing role in dsRNA surveillance (Figure 5B). Lenalidomide treatment of LenR cells failed to induce ISGs and IFNs to the extent observed in LenS cells (Figure 5C), suggesting a diminished dsRNA-sensing IFN pathway response associated with lenalidomide resistance. However, ADAR1 KD in LenR cells rescued lenalidomide sensitivity, activated dsRNA-sensing pathways, and enhanced IFN responses (Figure 5D-G). These findings, altogether, reinforce the notion that ADAR1 is functionally important in IMiD resistance through the suppression of dsRNA-sensing responses.

ADAR1 promotes lenalidomide resistance in LenR cells. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of cellular dsRNA with J2 antibody in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells (top). Orange-red fluorescence indicates dsRNA signals, and blue fluorescence indicates DAPI staining. Scale bars represent 20 μm. Bar graph quantification of the relative mean cytoplasmic dsRNA fluorescence intensity (bottom). (B) Sanger sequencing chromatograms illustrating the RNA editing levels of an ADAR1 target gene (SRP9) in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells. Percentages denote the editing frequencies of the corresponding editing site indicated by the arrow. (C) Relative mRNA expression of CXCL10, IFN-α, and IFN-β in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells after treatment with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 72 hours, determined by qRT-PCR. (D) Western blot validation of the effect of ADAR1 shRNA KD in KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells. Blot with ADAR1 p150 and ADAR1 p110 was probed with ab88574 (Abcam), and the blot with only ADAR1 p150 was immunoblotted with ab126745 (Abcam). (E) Cell viability of ADAR1-KD KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CTG assay. (F) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), and the dsRNA sensors-mediated signaling in ADAR1-KD KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells after treatment with lenalidomide (1 μM or 10 μM) for 72 hours (left). The bar graphs (right) summarize p-PKR, p-IRF3 and p-eIF2α band intensities normalized to GAPDH and total protein content, quantified via ImageJ. Densitometry analyses for the relative protein expression normalized to GAPDH are displayed below the western blots. (G) Heat map showing the normalized mRNA expression of ISGs and (IFNs: IFN-α and IFN-β) in ADAR1-KD KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells treated with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 72 hours, determined by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, as determined by two-tailed Student t test.

ADAR1 promotes lenalidomide resistance in LenR cells. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of cellular dsRNA with J2 antibody in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells (top). Orange-red fluorescence indicates dsRNA signals, and blue fluorescence indicates DAPI staining. Scale bars represent 20 μm. Bar graph quantification of the relative mean cytoplasmic dsRNA fluorescence intensity (bottom). (B) Sanger sequencing chromatograms illustrating the RNA editing levels of an ADAR1 target gene (SRP9) in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells. Percentages denote the editing frequencies of the corresponding editing site indicated by the arrow. (C) Relative mRNA expression of CXCL10, IFN-α, and IFN-β in isogenic KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells after treatment with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 72 hours, determined by qRT-PCR. (D) Western blot validation of the effect of ADAR1 shRNA KD in KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells. Blot with ADAR1 p150 and ADAR1 p110 was probed with ab88574 (Abcam), and the blot with only ADAR1 p150 was immunoblotted with ab126745 (Abcam). (E) Cell viability of ADAR1-KD KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CTG assay. (F) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates for total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), and the dsRNA sensors-mediated signaling in ADAR1-KD KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells after treatment with lenalidomide (1 μM or 10 μM) for 72 hours (left). The bar graphs (right) summarize p-PKR, p-IRF3 and p-eIF2α band intensities normalized to GAPDH and total protein content, quantified via ImageJ. Densitometry analyses for the relative protein expression normalized to GAPDH are displayed below the western blots. (G) Heat map showing the normalized mRNA expression of ISGs and (IFNs: IFN-α and IFN-β) in ADAR1-KD KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells treated with lenalidomide (10 μM) for 72 hours, determined by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, as determined by two-tailed Student t test.

In contrast to lenalidomide-treated models, bortezomib and dexamethasone treatments did not increase J2 signal (supplemental Figure 8A-B). Furthermore, both bortezomib and dexamethasone treatments generally suppressed the dsRNA-sensing pathways (with the exception of phosphorylated IRF3 in bortezomib-treated cells; supplemental Figure 8C-D), indicating that ADAR1’s modulation of the dsRNA sensor–ISG immune pathways is specific to IMiDs.

MDA5 is a key dsRNA sensor for lenalidomide sensitivity in ADAR1-deficient MM cells

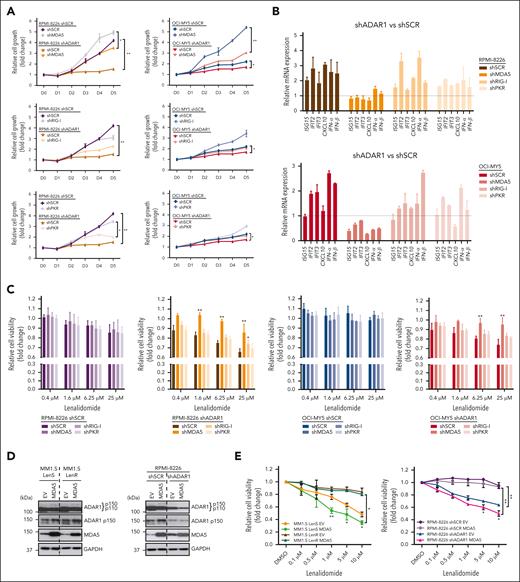

Having established the importance of dsRNA-sensing pathway in lenalidomide treatment, we proceed to identify which dsRNA sensor(s) that directly mediate lenalidomide sensitivity. We manipulated the stable ADAR1 KD cells to differentially express MDA5, RIG-I, or PKR (supplemental Figure 9). Notably, the depletion of MDA5 significantly rescued the growth inhibitory effects of ADAR1 KD, restoring cell growth to levels comparable with (RPMI-8226) or even exceeding (OCI-MY5) those observed in ADAR1-WT cells. In contrast, KD of RIG-I or PKR had only minimal to modest effects on rescuing the growth-inhibitory effects of ADAR1 loss in both cell lines (Figure 6A).

MDA5 activation enhances lenalidomide sensitivity in ADAR1-deficient MM cells. (A) Cell growth curves of MDA5-KD, RIG-I-KD, or PKR-KD in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells over 5 days, determined using CTG assay. (B) Relative mRNA expression of ISGs and IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) in MDA5-KD, RIG-I-KD, or PKR-KD in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells, determined by qRT-PCR and compared against their respective shSCR. (C) Cell viability of MDA5-KD, RIG-I-KD, or PKR-KD in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CTG assay. (D) Western blot validation of the OE of MDA5 in KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells. Blot with ADAR1 p150 and ADAR1 p110 was probed with ab88574 (Abcam), and the blot with only ADAR1 p150 was immunoblotted with ab126745 (Abcam). (E) Cell viability of MDA5-overexpressing KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CTG assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Significance differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test and for the line bracket by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01.

MDA5 activation enhances lenalidomide sensitivity in ADAR1-deficient MM cells. (A) Cell growth curves of MDA5-KD, RIG-I-KD, or PKR-KD in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells over 5 days, determined using CTG assay. (B) Relative mRNA expression of ISGs and IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) in MDA5-KD, RIG-I-KD, or PKR-KD in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells, determined by qRT-PCR and compared against their respective shSCR. (C) Cell viability of MDA5-KD, RIG-I-KD, or PKR-KD in ADAR1-KD RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CTG assay. (D) Western blot validation of the OE of MDA5 in KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells. Blot with ADAR1 p150 and ADAR1 p110 was probed with ab88574 (Abcam), and the blot with only ADAR1 p150 was immunoblotted with ab126745 (Abcam). (E) Cell viability of MDA5-overexpressing KMS-11 and MM1.S LenR cells at 6 days after treatment with increasing concentration of lenalidomide, determined by CTG assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Significance differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test and for the line bracket by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01.

We also evaluated the effect of dsRNA sensor depletion on the expression of IFN response genes in ADAR1-KD cells. MDA5 KD resulted in a marked reduction in IFNs and ISG, whereas RIG-I and PKR KDs had minimal effect on these gene expressions (Figure 6B).

To further confirm MDA5’s role in mediating lenalidomide sensitivity, we assessed the response of these cells to lenalidomide treatment. MDA5 KD increased lenalidomide resistance in ADAR1-deficient cells (Figure 6C). Conversely, OE of MDA5 in LenS (MM1.S) and ADAR1-KD (RPMI-8226) cells enhanced lenalidomide sensitivity, whereas this effect was not observed in MM1.S LenR cells or RPMI-8226 shSCR cells, which have high ADAR1 expression (Figure 6D-E). Overall, these findings demonstrate that lenalidomide activates the dsRNA-sensing pathway in MM, predominantly through MDA5, in low ADAR1 setting. This underscores ADAR1’s pivotal role in the dsRNA-sensing pathway that mediates lenalidomide resistance.

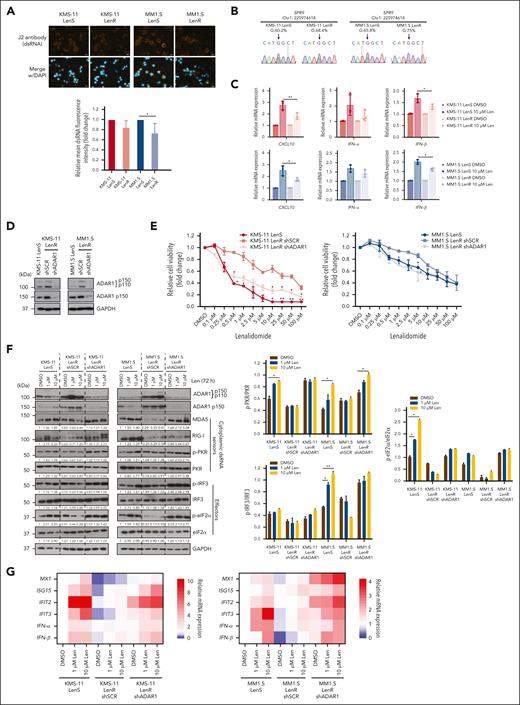

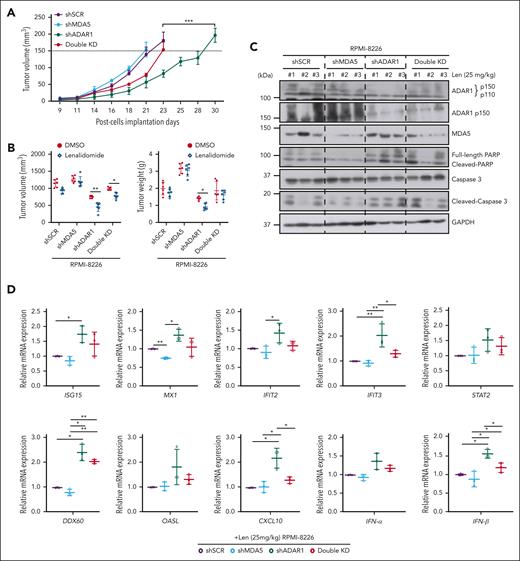

ADAR1 inhibition activates dsRNA-sensing responses and enhances lenalidomide sensitivity in vivo

Finally, to validate our findings in vivo, we established subcutaneous xenografts of RPMI-8226 cells expressing differential ADAR1 and MDA5 levels. RNA editing was confirmed by assessing A-to-I RNA editing frequency at known ADAR1 target sites (supplemental Figure 10A-B). ADAR1 KD significantly reduced tumorigenicity, consistent with previous study,25 whereas loss of MDA5 resulted in more aggressive tumors. Importantly, depleting MDA5 in ADAR1 KD cells (double KD) partially restored their tumorigenic potential (Figure 7A), corroborating our in vitro findings (Figure 6A).

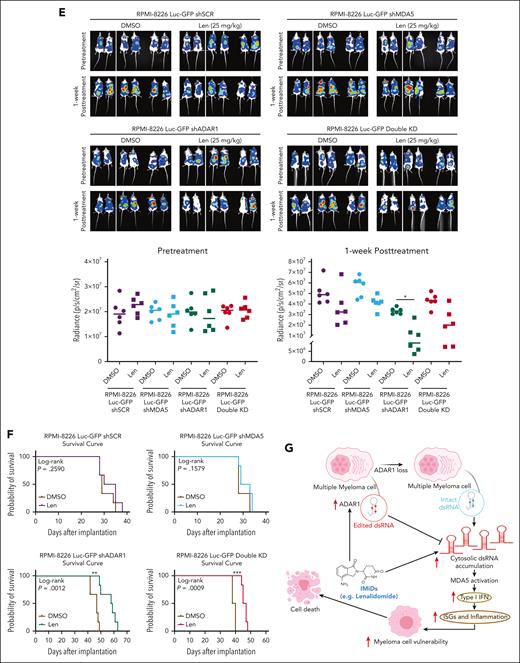

ADAR1 inhibition enhances lenalidomide sensitivity in vivo in MM mouse models. (A) Tumor growth profiles of RPMI-8226-isogenic cells with differential ADAR1 and MDA5 expression in subcutaneous MM xenograft models. Double-KD represents concurrent ADAR1 and MDA5 KD. Once tumors reached 150 mm3, mice were administered with lenalidomide (25 mg/kg) or DMSO (vehicle control) intraperitoneally, for four consecutive days per week for two weeks (n = 6 mice per group). Significant differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test. (B) Tumor volume and weight of tumors isolated from the respective isogenic RPMI-8226 subcutaneous xenograft mice groups after two weeks of lenalidomide treatment (25 mg/kg). Significant differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test. (C) Western blot analysis of tumor lysates from RPMI-8226 subcutaneous xenografts, assessing levels of total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), MDA5, PARP, and cleaved caspase-3 after two weeks of lenalidomide treatment (25 mg/kg). #1 #2 #3 refer to the tumors isolated from the different respective isogenic RPMI-8226 subcutaneous xenograft mice (shSCR, shMDA5, shADAR1, and Double KD) at two weeks after lenalidomide treatment (25 mg/kg). (D) Relative mRNA expression of ISGs and IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) in tumors isolated from the respective isogenic RPMI-8226 subcutaneous xenograft mice groups after two weeks posttreatment with lenalidomide (25 mg/kg), determined by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Significant differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test. (E) Bioluminescence imaging of total body bioluminescence in intravenous (IV) disseminated xenografts with RPMI-8226 firefly luciferase-green fluorescent protein (Luc-GFP)–isogenic cells at pretreatment (day 0 of DMSO/lenalidomide randomization) and one week after treatment of DMSO/lenalidomide treatment (25 mg/kg). Significant differences were determined by 2-tailed Student t test. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the IV disseminated xenografts transplanted with RPMI-8226 Luc-GFP-isogenic cells treated with lenalidomide (25 mg/kg) or DMSO control for one week. OS was followed till mice were humanely euthanized at the first sign of morbidity. IV disseminated xenograft mice survival curves were analyzed using the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001. (G) Proposed model of mechanism underlying the role of ADAR1 in regulating resistance to IMiDs in MM. Increased levels of ADAR1 in MM cells suppress IMiD-induced dsRNA-sensing pathways through RNA editing, which destabilizes dsRNA and limits their recognition by dsRNA sensors. In contrast, ADAR1 loss sensitizes myeloma cells to IMiD (lenalidomide) by activating the MDA5 dsRNA-sensing pathway, leading to increased dsRNA detection, inflammation, and IFN response.

ADAR1 inhibition enhances lenalidomide sensitivity in vivo in MM mouse models. (A) Tumor growth profiles of RPMI-8226-isogenic cells with differential ADAR1 and MDA5 expression in subcutaneous MM xenograft models. Double-KD represents concurrent ADAR1 and MDA5 KD. Once tumors reached 150 mm3, mice were administered with lenalidomide (25 mg/kg) or DMSO (vehicle control) intraperitoneally, for four consecutive days per week for two weeks (n = 6 mice per group). Significant differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test. (B) Tumor volume and weight of tumors isolated from the respective isogenic RPMI-8226 subcutaneous xenograft mice groups after two weeks of lenalidomide treatment (25 mg/kg). Significant differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test. (C) Western blot analysis of tumor lysates from RPMI-8226 subcutaneous xenografts, assessing levels of total ADAR1 (ab88574; Abcam), ADAR1 p150 (ab126745; Abcam), MDA5, PARP, and cleaved caspase-3 after two weeks of lenalidomide treatment (25 mg/kg). #1 #2 #3 refer to the tumors isolated from the different respective isogenic RPMI-8226 subcutaneous xenograft mice (shSCR, shMDA5, shADAR1, and Double KD) at two weeks after lenalidomide treatment (25 mg/kg). (D) Relative mRNA expression of ISGs and IFNs (IFN-α and IFN-β) in tumors isolated from the respective isogenic RPMI-8226 subcutaneous xenograft mice groups after two weeks posttreatment with lenalidomide (25 mg/kg), determined by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD of biological triplicates. Significant differences were determined by two-tailed Student t test. (E) Bioluminescence imaging of total body bioluminescence in intravenous (IV) disseminated xenografts with RPMI-8226 firefly luciferase-green fluorescent protein (Luc-GFP)–isogenic cells at pretreatment (day 0 of DMSO/lenalidomide randomization) and one week after treatment of DMSO/lenalidomide treatment (25 mg/kg). Significant differences were determined by 2-tailed Student t test. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the IV disseminated xenografts transplanted with RPMI-8226 Luc-GFP-isogenic cells treated with lenalidomide (25 mg/kg) or DMSO control for one week. OS was followed till mice were humanely euthanized at the first sign of morbidity. IV disseminated xenograft mice survival curves were analyzed using the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. Statistical significance is denoted by ∗P ≤ 0.05; ∗∗P ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001. (G) Proposed model of mechanism underlying the role of ADAR1 in regulating resistance to IMiDs in MM. Increased levels of ADAR1 in MM cells suppress IMiD-induced dsRNA-sensing pathways through RNA editing, which destabilizes dsRNA and limits their recognition by dsRNA sensors. In contrast, ADAR1 loss sensitizes myeloma cells to IMiD (lenalidomide) by activating the MDA5 dsRNA-sensing pathway, leading to increased dsRNA detection, inflammation, and IFN response.

We then assessed whether ADAR1 inhibition could enhance sensitivity to lenalidomide in these xenografts (supplemental Figure 10C). Lenalidomide treatment significantly reduced tumor growth, volume, and weight, more so in ADAR1 KD tumors than those with shSCR or MDA5 KD (Figure 7B; supplemental Figure 10D). Additionally, ADAR1 KD tumors showed increased cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 7C) and higher expression of IFNs and ISGs (Figure 7D). Conversely, double KD tumors showed a rescue of the above phenotypes after lenalidomide treatment, supporting that MDA5 may reverse the tumor suppression from ADAR1 KD.

To further corroborate these findings in a more biologically relevant MM model, we established intravenous (IV) disseminated xenografts using RPMI-8226 cells expressing firefly luciferase–green fluorescent protein (Luc-GFP) with differential ADAR1 and MDA5 levels (supplemental Figure 10E-F). Consistent with the subcutaneous model, ADAR1-KD mice displayed increased lenalidomide sensitivity. In contrast, double KD showed partial resistance, and those with MDA5 loss or shSCR were the least responsive to lenalidomide (Figure 7E). Moreover, ADAR1-KD mice had significantly prolonged survival compared with mice with double KD, shSCR, or MDA5 KD (Figure 7F; supplemental Figure 11G-H).

Translational relevance of ADAR1 inhibition with lenalidomide treatment

Our results thus far underscore the role of ADAR1-mediated RNA editing in lenalidomide resistance, suggesting that targeting ADAR1 or modulating its activity could improve IMiD efficacy. To explore this further, we evaluated the combination of lenalidomide and 8-azaadenosine (that has previously been reported to have activity against ADAR1) in LenR RPMI-8226 and OCI-MY5 cells. In line with previous studies in other cancers,44,45 8-azaadenoosine reduced ADAR1 expression and its RNA editing activity (supplemental Figure 11A-B). Importantly, this combination enhanced lenalidomide sensitivity in both cell lines (supplemental Figure 11C). Collectively, these results suggest that inhibiting ADAR1 creates a therapeutic vulnerability to lenalidomide. The proposed mechanistic model is demonstrated in Figure 7G.

Discussion

Although IMiDs have revolutionized the treatment of MM, resistance to these therapies remains a significant challenge, with nearly all patients eventually developing resistance. Although abnormalities in CRBN and its associated cullin-RING ligase components have been well documented,7-11 recent research has unveiled additional complexity beyond the CRBN pathway. These include aberrant activation of signaling pathways (such as interleukin-6/Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 [IL-6/STAT3], wingless/beta-catenin [Wnt/β-catenin], and mitogen-activated protein kinase [MAPK] kinase/extracellular signal–regulated kinase [MEK/ERK]), upregulation of CDK6, dysregulated expression of cell surface receptors (such as CD138, CD33, and CD45), epigenetic alterations, and modulation of the immune microenvironment through the secretion of extracellular vesicles, lactate, and chemokines.8,12,13,16-21 More recently, transcriptional factors plasticity have highlighted the redundancy of IMiD-induced IKZF1/3 degradation as compensatory activation of alternative transcriptional circuits of ETV4, and BATF was able to sustain the expression of IRF4 and MYC, thereby conferring resistance to IMiDs in MM.14,15 Together with these emerging evidence on mechanisms beyond the CRBN pathway, our study identifies ADAR1 and its RNA editing role in deregulating dsRNA-sensing pathway to confer lenalidomide resistance. Although our analyses on the CoMMpass data set and our LenR models did not reveal alterations in CRBN pathway genes in IMiD-resistant cases, we found that ADAR1 expression closely correlates with lenalidomide sensitivity.

Previous studies have associated ADAR1 with resistance to immunotherapies, including checkpoint inhibitors31 and IMiDs,25 but the specific mechanisms by which aberrant RNA editing influences IMiD responses in MM have remained largely unexplored. Unlike earlier research that focused on genetic lesions and protein expression changes,7,8,13,46 our study offers a novel perspective by examining another biological component, RNA biology, specifically the integrity of dsRNA and dsRNA-sensing pathways, in mediating lenalidomide resistance. We demonstrate that ADAR1 regulates IMiD sensitivity by regulating dsRNA-sensing pathways, potentially independent of the canonical CRBN pathway. Mechanistically, IMiDs induce dsRNA accumulation, which activates downstream IFN responses and MM cell inhibition. ADAR1, in turn, through its aberrant RNA editing activity, limits these dsRNA-sensing responses, thus, neutralizing the cytotoxic effects of IMiDs. Notably, we identify MDA5 as the predominant dsRNA sensor mediating IMiD sensitivity, specifically in low ADAR1 settings, underscoring ADAR1 as the key player in the dsRNA-sensing pathway and its role in lenalidomide resistance.

IMiDs are known to alter the cytokine profile in the bone marrow milieu to promote immune cells recruitment47,48; but of great interest, the mechanisms driving this cytokine production have not been thoroughly explored. Our study reveals that lenalidomide-induced increase in ISG expression and IFN responses can be driven by dsRNA accumulation and subsequent activation of the dsRNA-sensing pathway. This finding elucidates how lenalidomide relies on the dsRNA-sensing pathway at the tumor-intrinsic level to stimulate cytokine production and enhance immune responses.

A key question arising from this work is how IMiDs induce cytoplasmic dsRNA accumulation to activate the dsRNA-sensing pathway. Recent studies have shown that the clinical efficacy of various therapies, such as chemotherapy, epigenetic inhibitors, and spliceosome inhibitors, partly stems from their ability to influence epigenetic remodeling and chromatin reorganization. This process can reactivate the transcription of transposable elements that are epigenetically silenced in normal physiological state.32,49-52 Such reactivation disrupts RNA metabolism, leading to the formation of secondary dsRNA structures and aberrant dsRNA accumulation, which ultimately trigger the dsRNA-sensing response and IFN signaling. Corroborating this notion, our preliminary in silico analyses (data not shown) showed that IMiD-treated MM cells indeed had an enrichment of transposable elements, particularly the endogenous retrovirus sequences. Although further investigation of this aspect is highly warranted, it is not within the scope of our study.

Previous studies have demonstrated that IMiDs can modulate epigenetic modifiers through IKZF1 and IKZF3, either promoting repression or activation through the recruitment of nuclear cofactors.53-56 In concordance, we observed that IKZF1/3 KD (replicating the biological effects of IMiDs) resulted in the accumulation of dsRNAs, with minimal alterations to the expression of IRF4 and MYC (supplemental Figure 5A). This, therefore, further suggests that IKZF1/3 may have a role beyond the canonical IRF4-MYC axis in mediating IMiD resistance. Here, we propose a plausible mechanism in which ADAR1-dsRNA-MDA5 and IKZF1/3 axes converge into a common pathway to activate the dsRNA-sensing pathway, thereby, regulating IMiD resistance (visual abstract).

Pomalidomide, a second-line therapy for lenalidomide-refractory patients, has an overall response rate of 30% to 40%.57,58 This, however, suggests that 60% to 70% of lenalidomide-refractory patients do not respond to pomalidomide, despite an intact CRBN pathway in these patients.9,46,59,60 This further highlights the involvement of mechanisms beyond the CRBN pathway, such as the deregulated ADAR1-dsRNA mechanism, in our instance, in mediating MM responses to IMiDs. We opine that this can also plausibly explain the cross-resistance observed in our LenR cells to pomalidomide (supplemental Figure 3F), because we did not find any abnormalities in the CRBN pathway in LenR cells but instead identified increased ADAR1 RNA editing and suppressed dsRNA-sensing responses.

Our data, therefore, provide rationale for targeting ADAR1 or modulating its activity to enhance the efficacy of IMiDs by inducing a cytotoxic inflammatory IFN cascade to potentially help overcome resistance. This has significant clinical implications, because gain/amp1q is a recurrent high-risk factor in IMiD-refractory patients with MM.27 Furthermore, the Myeloma XI trial showed that patients with isolated 1q gain did not benefit from lenalidomide maintenance,61 suggesting that ADAR1 OE associated with gain/amp1q may therefore be, in part, the underlying factor that contribute to IMiD resistance in this group. Unlike common tumor drivers such as KRAS and TP53, ADAR1 mutations are rare (<5%) in various malignancies and infrequent in MM (supplemental Table 3).62-64 Therefore, targeting ADAR1 presents a promising therapeutic strategy. Our findings support this approach, because 8-azaadenoosine was shown to increase lenalidomide sensitivity in LenR cells (supplemental Figure 11C). However, 8-azaadenosine may not be a specific ADAR1 inhibitor,65 highlighting the need for the development of more specific ADAR1 inhibitors. Several promising anti-ADAR1 compounds, including ZYS-1 and Rebecsinib, are currently in preclinical development33,66 and evaluating their efficacy in MM is a critical area for future research.

In conclusion, our study uncovers a novel RNA-based mechanism underlying lenalidomide resistance that extends beyond the CRBN-IKZF1/IKZF3 proteasomal degradation pathway. We provide compelling evidence that the dysregulation of the ADAR1-dsRNA-MDA5-ISG axis contributes to IMiD resistance (Figure 7G). Further research should explore how the loss of IKZF1 and/or IKZF3 induces dsRNA accumulation and dsRNA-sensing responses and whether these mechanisms are relevant to other cancers treated with IMiDs. Additionally, it remains to be determined whether IMiD-induced dsRNA upregulation is a downstream effect of IRF4 or MYC suppression or whether distinct pathways mediate IMiD cytotoxicity. As new IMiD analogues, such as CRBN-E3 ligase modulators, progress through clinical trials,67,68 and as there may be other drugs harboring similar pharmacological profile in the future, our findings on ADAR1 and the dsRNA-sensing mechanism in MM are highly pertinent and may guide the development of more effective therapeutic strategies and drug combinations to overcome treatment resistance and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Diagrams were created with BioRender.com.

W.J.C. is supported by the National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Singapore Translational Research Investigator Award. This research is funded by Singapore Ministry of Education Tier 2 grant (MOE2019-T2-1-083) and is partly supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore and the Singapore Ministry of Education under the Research Centres of Excellence initiative as well as the RNA Biology Center at the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, National University of Singapore, as part of funding under the Singapore Ministry of Education Tier 3 grant (MOE2014-T3-1-006).

Authorship

Contribution: M.Y.K. contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing the manuscript draft, and reviewing, editing, and finalization of the manuscript; T.-H.C. performed bioinformatic analysis of CoMMpass data; N.X.N.T., S.H.M.T., and J.Z. contributed to the in vivo mouse work; T.K.T. performed bioinformatic analysis of whole-exome sequencing data of lenalidomide-resistant cells and RNA sequencing data from publicly available studies; L.C. contributed to funding acquisition, resources, supervision, and reviewing the manuscript; W.J.C. contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, and reviewing and editing the manuscript; and P.J.T. contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, methodology, formal analysis, writing the manuscript draft, and reviewing, editing, and finalization of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Phaik Ju Teoh, Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117599, Singapore; email: mdctpju@nus.edu.sg; Wee Joo Chng, Department of Hematology-Oncology, National University Cancer Institute, National University Health System, Singapore, 119228, Singapore; email: mdccwj@nus.edu.sg; and Leilei Chen, Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117599, Singapore; email: polly_chen@nus.edu.sg.

References

Author notes

Whole-exome sequencing data generated for this study have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (BioProject ID: PRJNA1073575).

Additional data supporting the key findings of this study are included within the article and its supplemental Files.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal