In this issue of Blood, Escherich et al1 investigate the role played by the DNA nucleotidyl exotransferase (DNTT) gene downregulation to induce resistance to inotuzumab ozogamycin (InO) in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

InO (Besponsa) is an antibody-drug conjugate approved for the treatment of relapsed and refractory B-ALL in adults. InO consists of a CD22-targeting immunoglobulin G4 humanized monoclonal antibody conjugated to calicheamicin.2 Calicheamicin is a potent toxin that binds to the DNA minor grove and induces double-strand breaks (DSBs).3 Based on its structural properties, one can anticipate that InO may have 2 Achilles’ heels: first, the alteration of CD22 expression and second, the induction of calicheamicin resistance.

In an article published in the July 4th issue of Blood, Zhao et al addressed the CD22 expression hypothesis.4 A comprehensive investigation of mechanisms of escape from InO therapy was conducted on samples obtained pre-InO therapy and at the time of relapse or refractoriness. The authors demonstrated that calicheamicin induces hypermutations by error-prone DNA damage repair, with multiple mutations per sample affecting the expression or the immunogenicity of CD22. These mechanisms were evidenced in 11% of the relapsed patients. They also reported that classical acquired loss-of-function mutations in TP53, ATM, and CDKN2A can explain InO resistance in some patients. In the last paragraph of the result section, the authors briefly described a striking association of DNTT loss and InO resistance found using a CRISPR screen.

DNTT, also known as terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, is a member of the Pol X family and contributes to the nonhomologous end joining pathway of DSB repair by incorporating nucleotides in a template-independent manner.5 Physiologically, DNTT is only expressed in early lymphocytes during V(D)J recombination. In B-ALL, DNTT expression is typically upregulated.6

Escherich et al now have elucidated the DNTT-induced mechanisms of resistance to calicheamicin. Using a systematic CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screening with the CD22+ B-ALL cell line Nalm6 to investigate the determinants of InO resistance, they found 3 major hits: the loss of the target epitope CD22 as expected, the already described BCL2 apoptosis pathway, and, interestingly, the loss of DNTT expression. They performed functional studies with the loss of DNTT in cell lines models and observed resistance to calicheamicin but also to other DSB-inducing drugs such as mitoxantrone, etoposide, mitomycin C, and daunorubicin. They also demonstrated that InO treatment elicits a markedly more attenuated DNA damage signaling in DNTT−/− B-ALL cells as compared with wild-type cells. Finally, they studied InO sensitivity and DNTT expression in B-ALL leukemic samples from 196 patients with newly diagnosed disease. DNTT expression was more variable than expected but correlated significantly with InO sensitivity.

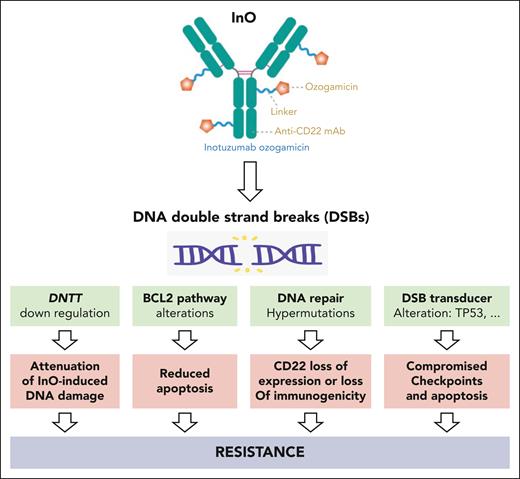

To summarize, we now have to consider mechanisms of resistance to InO: first, mechanisms related to the blast intrinsic characteristics with the classical acquired loss-of-function mutations in TP53, ATM, or CDKN2A including BCL2 apoptosis pathway alterations; second, InO-induced hypermutations secondary to error-prone DNA damage repair affecting the expression or the immunogenicity of CD22; and third, DNTT downregulation inducing the attenuation of InO-induced DNA damage by an unknown mechanism (see figure).

InO induces DNA DSBs. Leukemic B-cells can resist InO by harboring alteration of DSB transducers, alteration of BCL2 pathway, reduced CD22 expression or immunogenicity secondary to hypermutations, and finally by lowering DNTT expression to attenuate InO-induced DNA damage.

InO induces DNA DSBs. Leukemic B-cells can resist InO by harboring alteration of DSB transducers, alteration of BCL2 pathway, reduced CD22 expression or immunogenicity secondary to hypermutations, and finally by lowering DNTT expression to attenuate InO-induced DNA damage.

How can we translate these results to our clinical practice? InO monotherapy is currently preferred to lower the risk of hematological toxicity and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, with the associated risk of inducing InO resistance. We therefore have to explore the best way to combine InO and low-intensity chemotherapy.7-9 Another strategy already tested is to combine InO with blinatumomab (NCT03739814) or venetoclax (NCT05016947). Finally, the use of InO in the context of minimal residual disease may lower the risk of resistance.10

To conclude, InO, also known as Leucothea, protected Ulysses from Poseidon. A better knowledge of the mechanisms involved in InO resistance will help to protect patients from B-cell leukemia.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal