In this issue of Blood, Ding and colleagues1 have described mechanisms of therapeutic escape in patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) of Philadelphia chromosome-like B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph-like ALL). These include a specific MYC dependency and senescence-associated stem cell–like features that can be successfully targeted by dual inhibition of JAK/STAT and BCL-2.

Ph-like (or BCR::ABL1-like) ALL is a common high-risk leukemia subtype characterized by dismal outcome to standard chemotherapy and high heterogeneity in underlying genetic alterations, which drive constitutive kinase signaling and gene expression profiles phenocopying those from BCR::ABL1-positive ALL.2 Recurrent genetic drivers include ABL class and JAK-STAT rearrangements with CRLF2 alterations being present in over 50% of Ph-like ALL cases.3 Despite initial enthusiasm in incorporating tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), responses have been variable, especially for Ph-like ALL with CRLF2/JAK2 alterations, suggesting incomplete oncogene addiction.4 This suboptimal outcome has prompted further exploration of alternative biological dependencies and therapeutic vulnerabilities (eg, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [PI3K], mechanistic target of rapamycin [mTOR], MEK, or BCL-2) that can synergize with TKIs. Consistent with this hypothesis, Ding et al used integrated transcriptional, epigenetic, and phosphoproteomic approaches to profile over time leukemic cells harvested from CRLF2-rearranged or ABL1-rearranged Ph-like ALL PDXs treated with TKIs. This comprehensive analysis enabled detection of dynamic signaling adaptations with pathway dependencies shifting during prolonged treatment (see figure). MYC activation and STAT5 phosphorylation were reduced upon short-term ruxolitinib treatment; conversely, cellular senescence and PI3K/mTOR signaling were upregulated. Interestingly, prolonged JAK/STAT inhibition reversed this pattern with upregulation of MYC and several signaling pathways, including Src family kinases, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and JAK/STAT5, suggesting a complex mechanism of therapeutic adaptation with cross talk between MYC and other cellular dependencies. Pharmacological inhibition of MYC by the inhibitor OMO-103 was more efficacious in inhibiting leukemia cell proliferation than ruxolitinib monotherapy, supporting its role as a therapeutic target. The authors hypothesized that the TKI-induced transient MYC suppression may facilitate emergence of leukemic cell subpopulations with incomplete TKI sensitivity, which expand with prolonged treatment. To test this hypothesis, they used multiome single-cell transcriptional and epigenomic sequencing to profile residual leukemic blasts harvested at different time points from PDXs treated with ruxolitinib, venetoclax, or their combination. Compared with bulk approaches, sequencing at the single-cell resolution has the ability to characterize each individual cell, thereby defining populations that can be rare at diagnosis but can expand under pharmacologic pressure.5 This analysis revealed differences in transcriptional cluster compositions across samples and treatment time points with variability across treatment groups of a dormant, noncycling leukemia cell subpopulation characterized by expression of inflammatory pathways, downregulation of MYC targets, and expression of a senescence gene signature.6 Intra- and intersample transcriptional changes can be due to different enrichment of cell developmental states, which have different cell cycle properties, transcriptional signatures, and drug sensitivity. The availability of large and comprehensive single-cell reference atlases of human hematopoietic development enables accurate annotation of cell developmental states in leukemic samples. Therefore, the authors projected leukemia cells on a wide distribution of (normal) B-cell developmental stages and observed that leukemic cells from this dormant population coclustered with normal stem and progenitor cells, mostly common lymphoid progenitors and multipotent progenitors. The enrichment of both senescence and stem/progenitor-like features led to the annotation of this population as senescence-associated stemness (SAS).6 Analysis of related epigenetic data further elucidated transcriptional features highlighting a mechanism primarily mediated by AP-1 factors, which have been previously implicated in numerous cellular processes, including proliferation, senescence, and malignant transformation.7 Interestingly, by analysis of chromatin immunoprecipitation data, the authors observed that AP-1 factors can bind to cis-regulatory regions of MYC providing a possible mechanism of MYC upregulation after initial suppression during ruxolitinib exposure. The SAS population was transiently depleted after short-term treatment with venetoclax (but not with ruxolitinib) and reexpanded at later time points. Notably, cotreatment with TKI and ruxolitinib almost fully eradicated the SAS population, demonstrating a greater advantage of the combinatorial treatment in preventing leukemic expansion compared with monotherapy approaches.

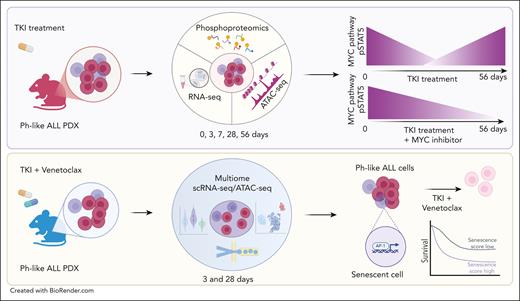

Inhibition of senescent stemlike subpopulations in Ph-like ALL. (Upper panel) Integrated transcriptomic, epigenomic, and phosphoproteomic analyses revealed dynamic shifts in MYC pathway and STAT5 phosphorylation (pSTAT5) during treatment with ruxolitinib. Dual inhibition of MYC and JAK/STAT5 pathway suppresses leukemia growth. (Lower panel) Single-cell sequencing of residual leukemic blasts post-TKI and BCL-2 inhibition identified a poor prognostic senescence-associated stem cell–like subpopulation regulated by AP-1, which is sensitive to dual JAK/STAT and BCL-2 inhibition. ATAC-seq, assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing; RNA-seq, whole transcriptome sequencing by RNA-sequencing.

Inhibition of senescent stemlike subpopulations in Ph-like ALL. (Upper panel) Integrated transcriptomic, epigenomic, and phosphoproteomic analyses revealed dynamic shifts in MYC pathway and STAT5 phosphorylation (pSTAT5) during treatment with ruxolitinib. Dual inhibition of MYC and JAK/STAT5 pathway suppresses leukemia growth. (Lower panel) Single-cell sequencing of residual leukemic blasts post-TKI and BCL-2 inhibition identified a poor prognostic senescence-associated stem cell–like subpopulation regulated by AP-1, which is sensitive to dual JAK/STAT and BCL-2 inhibition. ATAC-seq, assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing; RNA-seq, whole transcriptome sequencing by RNA-sequencing.

It is critical to acknowledge the challenge in teasing out senescence vs quiescence without functional experimental studies. In contrast to cellular quiescence, senescence has been historically considered a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest in which cells remain metabolically active and produce inflammatory signals. β-Galactosidase (β-gal) activity serves as a reliable marker to experimentally differentiate senescent cells from quiescent ones. However, in this study, the senescence-associated SA-β-gal analysis was conducted in vitro using cell lines, rather than in PDX samples. Notably, senescence can be “awakened” in cancer cells by oncogene expression (eg, restored MYC expression after long-term treatment with ruxolitinib), contributing to disease expansion. In a retrospective analysis of publicly available transcriptomic data from pediatric B-ALL samples, the SAS blast signature was associated with worse overall survival and event-free survival in children with B-ALL independent of sex, diagnostic white blood cell count, or central nervous system status factors. Moreover, this population was also enriched in B-ALL subtypes characterized by lineage plasticity potential (eg, KMT2A- and ZNF384-rearranged B-ALL). This observation is consistent with recent findings suggesting a worse outcome of leukemia subgroups with high multipotency potential.8

In conclusion, this study reveals MYC as a therapeutically targetable codependency in Ph-like ALL and defines a leukemia cell subpopulation with senescence-associated stem cell–like features that is sensitive to the combination of JAK/STAT and BCL-2 inhibition, underscoring the importance of targeting multiple vulnerabilities. Future studies should focus on validating these findings in leukemic cells from patients treated in clinical trials with TKI and senolytics (eg, venetoclax) and on exploring the role of the immune tumor microenvironment in triggering cellular senescence and inflammation. Moreover, since CRLF2-rearranged Ph-like ALL has shown excellent responses to immunotherapy-based approaches,9 future studies analyzing the role of the SAS population postimmunotherapy (alone or in combination with TKI) should be prioritized. Finally, additional studies are required to further characterize the role of RAS mutations in conferring resistance to TKI and BCL-2 inhibition, as recently investigated in acute myeloid leukemia cells.10 Overall, all these studies support a brighter future for outcome in Ph-like ALL.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: I.I. declares consultation fee from Arima genomics and travel costs paid by Mission Bio and Takara.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal