In this issue of Blood, Baskar et al describe an innovative approach to enhance CD20 antibody efficacy by employing their complement-activating capacity to deposit C3d as neoantigen for novel antibodies in xenografted mouse models.1

The complement system is a tightly controlled part of the innate immune system with important roles in host defense but also in the pathology of certain diseases.2 Thus, many approaches to target complement elements are in preclinical and clinical development, with more success in blocking than activating or enhancing the complement system.3 In vitro, complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) contributes to the mechanisms of action of some but not all tumor-directed monoclonal antibodies, and a clear contribution in vivo has been notoriously difficult to demonstrate. CD20 antibodies like rituximab (the first monoclonal antibody approved by the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] for malignancies) have been the workhorse used to explore this issue. Despite its broad clinical application in patients with almost all subtypes of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mechanisms of action and of resistance to this and follow-up CD20 antibodies like ofatumumab or obinutuzumab are still a topic of intensive investigation.

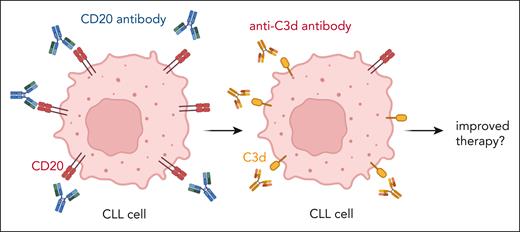

The study from Baskar et al demonstrates that chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells from patients during CD20 antibody therapy display significantly reduced levels of CD20 expression, which is probably explained by trogocytosis of antigen-antibody complexes from the tumor cell surface. At the same time, these cells are loaded with membrane-bound complement components (such as C3d, see figure), suggesting that complement deposition occurred without formation of the terminal membrane attack complex leading to tumor cell lysis. In their article, Baskar et al describe the generation and functional characterization of novel C3d antibodies, which act synergistically with CD20 antibodies in xenografted mouse models. In vitro, these C3d antibodies can trigger antibody-dependent cell-mediated phagocyosis (ADCP) and CDC of C3d-coated tumor cells. However, which of these mechanisms of action is relevant in vivo needs to be determined. This issue is not only of academic interest, since both mechanisms of action can be manipulated today by engineering the Fc part of antibodies. For example, enhancing or deleting Fc receptor binding by protein engineering or glycoengineering of the Fc part of antibodies to enhance ADCP and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) are standard technologies, which have led to FDA-approved antibodies like, for example, obinutuzumab.4 Engineering the complement-activating capacity of therapeutic antibodies is lagging behind, but several preclinical approaches appear promising.5 For example, point mutations in the Fc domain (eg, E345K) trigger hexamerization of antibodies after antigen binding on the tumor cell surface, which provides optimized stochiometry for the recruitment of hexameric C1q, leading to improved complement deposition and CDC.6

CD20 antibodies segregate into 2 classes, which differ in their predominant effector mechanisms and in their binding stoichiometry.7 In the study by Baskar et al, only the type 1 antibodies rituximab and ofatumumab, but not the type 2 antibody obinituzumab, were investigated. Ofatumumab is known to have the highest CDC activity but is no longer available for lymphoma therapy. In CLL therapy, the type 2 CD20 antibody obinituzumab is widely used, which is less active in CDC but enhanced for ADCC activity. Thus, it remains to be determined which of the CD20 antibodies would be the ideal candidate for this approach. The same holds true for the different C3d antibodies, which have not been compared in functional activity. Since only immunodeficient mouse models were used, potentially important links to the adaptive immune response could not be addressed.

Furthermore, the concept of the present study is not completely new, since targeting C3b and its breakdown product C3b(i) on CD20+ cells treated with rituximab has been suggested before.8

The results presented in this article will require further preclinical evaluation of this novel approach. With respect to potential toxicity, the authors show that CD20 antibodies in vitro deposit C3d only on B cells but not on other peripheral blood cells, including erythrocytes. Early toxicology studies with C3d antibodies alone or in combination with CD20 antibodies in nonhuman primates should be rather straightforward, since many of the novel C3d antibodies cross-react with cynomolgus monkeys. Monitoring peripheral blood B-cell depletion in these animals has been established as a rather reliable surrogate for therapeutic efficacy in clinical studies. However, toxicity of C3d antibodies in patients may occur when auto- or alloantibodies have deposited C3d on cells (eg, erythrocytes) or in tissues (eg, kidneys). For example, autoimmune hemolytic anemia is a common complication in patients with CLL, but also alloantibodies can be induced when patients received transfusions. Although C3d deposition on red blood cells can easily be measured by routine assays, its deposition on other cells or tissues will be more difficult to detect. Carefully defined exclusion criteria for clinical studies may help to limit these risks and complement-inhibiting approaches could be considered in cases of severe toxicity.2

An important issue for future research will also be the evaluation of antibodies against other B cell–expressed target antigens like CD19 or CD38, against which approved antibodies are available. Antibodies against these antigens differ widely in their capacity to trigger CDC and complement deposition on tumor cells. Although conventional CD19 antibodies (eg, tafasitamab) do not trigger CDC, they can do upon Fc engineering.9 The prototypic CD38 antibody daratumumab has intrinsic CDC activity, which can be further enhanced by hexabody mutations. Daratumumab is widely used in patients with multiple myeloma and primary (AL) amyloidosis and has recently shown promising activity in patients with T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia.10 These antibodies and targets would be immediate candidates for a C3d-cotargeting strategy. More challenging will probably be the application in solid tumors, where most unmodified tumor-targeting antibodies do not activate complement. However, also here the landscape is changing due to Fc engineering and combinations of antibodies and bispecific molecules.5 However, the paucity of truly tumor-specific antibodies may raise concerns of on-target, off-tumor toxicity, which is less critical for B cell–directed antibodies. Alternatively, or additionally to C3d, other complement components deposited on tumor cells could be targeted (eg, C4d). Thus, the study by Baskar et al provides exciting and broad opportunities to enhance antibody-based immunotherapy, which hopefully will be explored rapidly.

Trogocytosis and complement activation by CD20 antibodies lead to loss of CD20 expression and gain of C3d deposition, which can serve as target for novel C3d antibodies. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Trogocytosis and complement activation by CD20 antibodies lead to loss of CD20 expression and gain of C3d deposition, which can serve as target for novel C3d antibodies. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.V. receives research funding from Commit BV, Denmark. J.L. is the scientific founder and a shareholder of TigaTx.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal