Abstract

In the setting of hybrid resistance, parental C57BL/6 bone marrow (BM) grafts are vigorously rejected by lethally irradiated (C57BL/6xDBA/2) F1 mice. However, F1 mice pretreated by continuous administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ) with a miniosmotic pump before BM grafting developed day-8 splenic colonies of donor origin. This inhibitory effect on rejection was reversible because F1 mice regained the capacity to reject parental BM when the pump ceased functioning. The appearance of only a small number of colonies with the administration of G-CSF soon after BM grafting suggested the importance in producing this inhibitory effect of pre-exposure of host mice to G-CSF. Because G-CSF administration with a syngeneic combination did not influence the number of colonies, an altered distribution of grafted precursors was unlikely. The absence of a reduction in the number of NK1.1-positive cells in G-CSF–treated mice suggested functional impairment of natural killer cells, major effectors in hybrid resistance, but further study is necessary to elucidate the mechanism underlying this phenomenon. However, our results indicate the importance of G-CSF as a regulator in a certain type of immune response and raise the possibility of clinical application in transplantation medicine.

GRANULOCYTE colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ) is a cytokine known to regulate the proliferation and maturation of neutrophilic granulocytes.1 Recent studies have also shown its potential role in upregulating the hematopoietic stem cell numbers in the peripheral blood.2-6 The latter function is particularly important in transplantation settings, because harvesting peripheral blood stem cells is easier than recovery from bone marrow (BM).

The biologic action of G-CSF has been investigated mainly in the maturational process of hematopoietic precursors and granulocytic cells. However, the function of G-CSF is not limited to these nonlymphoid cells. Our recent study clearly showed that G-CSF acts to increase the number of mature lymphocytes when expressed as a transgene.7 It is therefore likely that G-CSF plays an important role in the maturation and/or regulation of the immune system, although only a few reports have described a potential G-CSF role in this system.7-13 We recently described the inhibitory effect of G-CSF on the hematopoietic allograft rejections both in mice transgenic for G-CSF and in mice treated with continuous administration of G-CSF.12 Because host natural killer (NK) cells are considered to participate in hematopoietic allograft rejection,14 our results suggest the impairment of NK cell function in G-CSF–expressing animals.

In this report, we further extend our observation that G-CSF has an inhibitory effect on the hematopoietic graft rejection system. By using a hybrid resistance system15 in which NK cells are major effectors of rejection,14 we have shown that preadministration of G-CSF to the recipient animals attenuates rejection and renders F1 mice capable of accepting parental BM cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.C57BL/6 (B6) and (C57BL/6xDBA2)F1 (B6D2F1) mice (8 to 12 weeks old) were purchased from Japan Clea Corp (Tokyo, Japan). Mice were maintained in accordance with guidelines of our institution and were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions throughout the experiments.

Reagents.All reagents were obtained from Wako Chemicals (Osaka, Japan), unless otherwise indicated.

BM grafting and splenic colony formation.BM cells from female B6 mice at the cell number indicated were intravenously injected into female B6D2F1 mice within 3 hours after irradiation (9 Gy at 250 rad/min). In some experiments, male B6 BM cells were used as grafts. The day of BM transfer was counted as day 0 throughout this study. Mice were maintained on antibiotics-containing water from day −6 until the end of the experiments. Acceptance of hematopoietic precursors by recipient mice was monitored by the appearance of splenic colonies. Thus, on day 8, the number of colonies that had developed on the spleen surface was counted under a dissecting microscope after application of Bouin's fixative. In some experiments, 20 μL of rabbit polyclonal antiasialo GM1 (AGM1) antibody was intravenously injected into the recipient F1 mice on day −1 to deplete NK cells.16 Six mice were used in each experiment and the average of three independent experiments is presented.

Administration of human G-CSF.Recombinant human G-CSF (provided by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan and Kirin Brewery Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was administered subcutaneously to B6D2F1 mice using a miniosmotic pump (alzet MODEL2002; 14 days of function; ALZA Corp, Palo Alto, CA) at 25 μg/kg/d, except as otherwise indicated.

Analysis of spleen colonies by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).The origin of splenic colonies was examined for the combination using male B6 BM cells as donors and female F1 mice as recipients. On day 8 after BM grafting, the spleen was removed and fixed in 90% ethanol and 10% phosphate-buffered saline.17 A small tissue fragment was extracted from the center of each colony, washed once with distilled water, and digested in 0.2 mL of buffer containing 500 mg/mL proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemica, Mannheim, Germany), 50 mmol/L Tris-chloride (pH 8.5), 1 mmol/L EDTA, and 0.5 % Tween 20 at 37°C with overnight shaking. The sample was then incubated at 95°C for 8 minutes and a 0.5 μL quantity was subjected to PCR amplification (94°C for 1 minute, 60°C for 2 minutes, and 72°C for 3 minutes for 35 cycles), using 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Kurabo, Tokyo, Japan), 5 pmol/L of each primer, and 200 μmol/L of dNTP (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) in a final volume of 50 μL buffer recommended by the manufacturer. For amplification of 292 bp of the Y-chromosome–specific sequence (sex-determining region Y [SRY]),18 the sense primer 5′-GACTGGTGACAATTGTCTAG-3′ and the antisense primer 5′-TAAAATGCCACTCCTCTGTG-3′ were used. As internal controls, 220 bp of β-actin sequence19 was amplified using the sense 5′-GTACCACAGGCATTGTGATG-3′ and the antisense 5′-GCAACATAGCACAGCTTCTC-3′ primers. Amplified PCR products were separated by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide.

Effect of G-CSF Administration on the Appearance of Splenic Colonies in Hybrid Resistance

| Recipient . | Treatment* . | Donor . | BM Cells† . | Day-8 Splenic Colony‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6D2F1 | (−) | B6 | 1 × 105 | 0.7 ± 1.2 |

| 2.5 × 105 | 0.7 ± 1.1 | |||

| 1 × 106 | 2.3 ± 1.5 | |||

| B6D2F1 | G-CSF | B6 | 1 × 105 | 3.0 ± 2.0 |

| 2.5 × 105 | 10.0 ± 3.9 | |||

| 1 × 106 | 25.3 ± 1.5 | |||

| B6D2F1 | AGM1 | B6 | 1 × 105 | 11.3 ± 3.5 |

| 2.5 × 105 | 21.0 ± 3.1 | |||

| B6 | (−) | B6 | 1 × 105 | 18.0 ± 1.7 |

| G-CSF | 1 × 105 | 19.0 ± 5.7 |

| Recipient . | Treatment* . | Donor . | BM Cells† . | Day-8 Splenic Colony‡ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6D2F1 | (−) | B6 | 1 × 105 | 0.7 ± 1.2 |

| 2.5 × 105 | 0.7 ± 1.1 | |||

| 1 × 106 | 2.3 ± 1.5 | |||

| B6D2F1 | G-CSF | B6 | 1 × 105 | 3.0 ± 2.0 |

| 2.5 × 105 | 10.0 ± 3.9 | |||

| 1 × 106 | 25.3 ± 1.5 | |||

| B6D2F1 | AGM1 | B6 | 1 × 105 | 11.3 ± 3.5 |

| 2.5 × 105 | 21.0 ± 3.1 | |||

| B6 | (−) | B6 | 1 × 105 | 18.0 ± 1.7 |

| G-CSF | 1 × 105 | 19.0 ± 5.7 |

G-CSF at 25 μg/kg/d was administered subcutaneously with a miniosmotic pump starting on day −14. AGM1 was injected on day −1.

Number of B6 BM cells transplanted.

Number of colonies represents the mean ± SD of three experiments.

Long-term hematopoietic chimerism.Donor B6 BM cells were depleted of T cells with anti-Thy1.2 antibody (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) plus complement and then grafted to F1 mice pretreated with or without G-CSF at 25 μg/kg/d for 14 days. On day 40, peripheral blood was obtained from alive animals and was double-stained with fluorescence isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti–H-2Db and phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti–H-2Dd monoclonal antibodies (PharMingen). The whole nucleated peripheral blood cell population was gated and the percentage of cells with donor (B6, H-2b/b) or recipient (B6D2F1, H-2b/d) phenotypes were calculated on a two-color histogram. The details of flow cytometrical analysis are described below.

Flow cytometrical analysis.Flow cytometrical analysis was performed on an EPICS-XL (Coulter, Hialeah, FL). Whole spleen cells were stained with PE-labeled anti-NK1.1 antibody PK136 (PharMingen) and FITC-labeled antimouse αβ T-cell receptor antibody H57-597 (PharMingen), and the positivity of the mononuclear cell fraction as defined by forward angle light scatter and side angle light scatter was analyzed.

Statistical analysis.Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed by Student's t-test to examine the statistical significance of differences.

RESULTS

G-CSF pretreatment of F1 hybrid mice before irradiation and parental BM grafting.To investigate the effect of G-CSF on the rejection of parental BM grafts by F1 hybrid mice, we used strain combinations recognized as being parental BM grafts vulnerable to NK-mediated rejection by F1 hybrids,14 ie, C57BL/6 (B6) as the donor and its F1 hybrid obtained from a cross with DBA2, (C57BL/6xDBA2)F1 (B6D2F1) as a recipient. We applied splenic colony assays to evaluate the magnitude of the rejection of parental B6 BM cells by B6D2F1. Classical rejection in hybrid resistance was shown in an experiment in which untreated B6D2F1 mice readily rejected parental B6 BM cells (Table 1). Inoculation of as many as 1 × 106 B6 BM cells produced only 2.3 ± 1.5 colonies. This value is in sharp contrast to the result obtained with a syngeneic combination in which only 1 × 105 B6 BM cells produced as many as 18.0 ± 1.7 colonies in B6 recipients (Table 1). However, rejection of parental BM cells could be abolished by treating the recipients with AGM1 antibody before BM grafting. Thus, 2.5 × 105 parental BM cells were sufficient to produce approximately 20 colonies in the AGM1-treated mice (Table 1). These results clearly show the rejection pattern in hybrid resistance and the significance of AGM1-sensitive cell populations as major effectors in rejection.

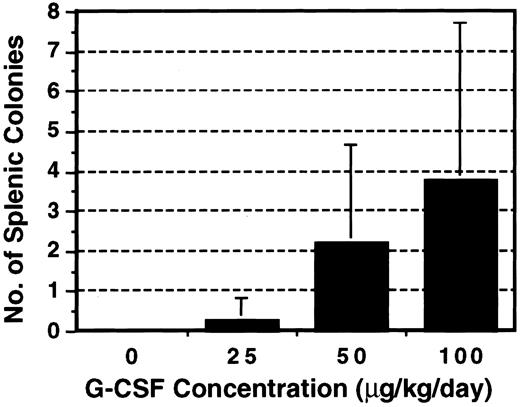

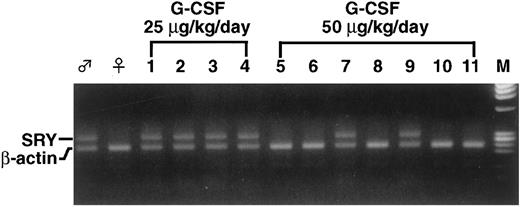

Before the G-CSF challenge in this system, we first examined to what extent G-CSF affects the induction of intrinsic colonies. G-CSF at various concentrations was administered to F1 mice with a miniosmotic pump for 14 days. The mice received irradiation but no BM graft and spleens were examined on day 8. As shown in Fig 1, colonies appeared and the number increased as the dosage of G-CSF was increased. Because less than 1 colony on average appeared at 25 μg/kg/d, this dosage was primarily used for further investigation. B6 BM was grafted into F1 mice pretreated with G-CSF at 25 μg/kg/d for 14 days. As shown in Table 1, as little as 2.5 × 105 BM cells produced 10.0 ± 3.9 colonies in the recipient F1 mice and the colony number increased when the BM cell number increased. To rule out the possibility of an endogenous origin of the splenic colonies that appeared in G-CSF–treated F1 mice, male B6 BM cells were grafted into G-CSF–treated female F1 mice and each colony was examined for the presence of a Y-chromosome–specific sequence by PCR. Most splenic colonies (38 of 39 examined) appearing in F1 mice pretreated with G-CSF at 25 μg/kg/d contained 292 bp of the SRY sequence (Table 2 and Fig 2), establishing the donor-origin of these colonies. However, at 50 μg/kg/d, the proportion of SRY-positive colonies was reduced to 25%.

Effect of G-CSF on the emergence of endogenous splenic colonies. B6D2F1 mice were treated with various concentrations of G-CSF for 14 days with a miniosmotic pump and then irradiated. No BM cells were grafted and the spleen was examined for the presence of colonies on day 8. The results represent the mean ± SD of three experiments.

Effect of G-CSF on the emergence of endogenous splenic colonies. B6D2F1 mice were treated with various concentrations of G-CSF for 14 days with a miniosmotic pump and then irradiated. No BM cells were grafted and the spleen was examined for the presence of colonies on day 8. The results represent the mean ± SD of three experiments.

Analysis of the Origin of Splenic Colonies by PCR

| G-CSF* . | No. of BM Cells . | Total . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 × 105 . | 2.5 × 105 . | 5 × 105 . | . |

| 25 μg/kg/d | 4/5† | 11/11 | 23/23 | 38/39 (97%) |

| 50 μg/kg/d | 1/6 | 2/10 | 5/16 | 8/32 (25%) |

| G-CSF* . | No. of BM Cells . | Total . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 1 × 105 . | 2.5 × 105 . | 5 × 105 . | . |

| 25 μg/kg/d | 4/5† | 11/11 | 23/23 | 38/39 (97%) |

| 50 μg/kg/d | 1/6 | 2/10 | 5/16 | 8/32 (25%) |

G-CSF was injected subcutaneously with a miniosmotic pump starting on day −14.

SRY-positive colonies/no. of colonies examined.

PCR analysis for the presence of donor-specific Y-chromosome sequence in splenic colonies. A small fragment of each colony was subjected to PCR analysis to detect the presence of the SRY sequence. Representative results using G-CSF concentrations of 25 or 50 μg/kg/d are shown. At 25 μg/kg/d, all colonies were positive for SRY (lanes 1 through 4), whereas only 2 colonies (lanes 7 and 9) were positive at 50 μg/kg/d (lanes 5 through 11). β-Actin used as an internal control was positive in all samples. (♂) Male, (♀) female, and (M) marker DNAs.

PCR analysis for the presence of donor-specific Y-chromosome sequence in splenic colonies. A small fragment of each colony was subjected to PCR analysis to detect the presence of the SRY sequence. Representative results using G-CSF concentrations of 25 or 50 μg/kg/d are shown. At 25 μg/kg/d, all colonies were positive for SRY (lanes 1 through 4), whereas only 2 colonies (lanes 7 and 9) were positive at 50 μg/kg/d (lanes 5 through 11). β-Actin used as an internal control was positive in all samples. (♂) Male, (♀) female, and (M) marker DNAs.

Finally, G-CSF was administered in syngeneic combination to determine whether G-CSF alters the distribution of progenitors capable of forming splenic colonies. B6 mice were pretreated for 14 days with G-CSF at 25 μg/kg/d, irradiated, and challenged with syngeneic BM cells. However, G-CSF treatment did not affect the splenic colony number as compared with G-CSF–nontreated controls (Table 1).

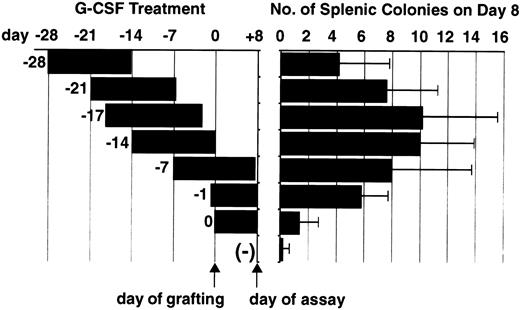

The effect of G-CSF administration after BM grafting on the appearance of splenic colonies.Although the prior administration of G-CSF to F1 recipients appeared to abolish hybrid resistance, as shown by the appearance of donor-originated splenic colonies, the possibility remained that G-CSF had augmented colony formation. To examine this possibility, we started G-CSF administration on day −7, day −1, or day 0 (on day 0 schedule, pump operation was initiated within 1 hour of BM grafting) and B6D2F1 mice were inoculated with 2.5 × 105 B6 BM cells (Fig 3). Inasmuch as the osmotic pump functioned for 14 days, these mice received G-CSF for an additional 7 or 8 days after BM grafting. The mice treated with hG-CSF before irradiation, ie, the day −7 and day −1 groups, developed 10 and 5.8 colonies, respectively, whereas the mice that received G-CSF treatment after irradiation developed only 1.4 colonies (Fig 3). These results showed that G-CSF has little effect on the proliferation of parental progenitor cells and that exposure of the recipients to G-CSF before BM grafting is critical for the attenuation of hybrid resistance.

G-CSF administration protocol and the appearance of splenic colonies. B6 BM cells were transplanted into B6D2F1 mice, following various G-CSF administration protocols, starting at various points from day −27 to day 0 as depicted. (−) represents BM grafting without G-CSF treatment. The day of BM grafting is counted as day 0 and the splenic colonies were counted on day 8, as indicated by arrows. Colony data represent the mean ± SD of three experiments.

G-CSF administration protocol and the appearance of splenic colonies. B6 BM cells were transplanted into B6D2F1 mice, following various G-CSF administration protocols, starting at various points from day −27 to day 0 as depicted. (−) represents BM grafting without G-CSF treatment. The day of BM grafting is counted as day 0 and the splenic colonies were counted on day 8, as indicated by arrows. Colony data represent the mean ± SD of three experiments.

Restoration of hybrid resistance after cessation of G-CSF administration.To examine whether the G-CSF–treated F1 mice regain the capacity to reject parental BM cells after the cessation of G-CSF administration, we set up experiments in which BM grafting was performed after the pumps had ceased functioning (Fig 3). As shown, the number of colonies tended to decrease if G-CSF administration had started earlier than day −14. No statistically significant decrease in colony number was observed in groups in which G-CSF was started on day −17 (10.2 ± 5.1) or day −21 (7.6 ± 3.7) when compared with G-CSF started on day −14 (10.0 ± 3.9), but the colony number in the group in which G-CSF was started on day −27 was significantly decreased (4.2 ± 3.6, P < .05). This experiment indicated that the attenuation of hybrid resistance induced by G-CSF is reversible but that this effect is still recognizable even when the G-CSF titer has returned to the baseline level.

Long-term hematopoietic chimerism in recipient mice pretreated with G-CSF.It is important to ascertain whether donor BM precursors capable of long-term hematopoietic reconstitution can be grafted into G-CSF–pretreated recipients. As shown in Table 3, G-CSF–pretreated recipient mice alive on day 40 contained donor-originated peripheral blood cells with the H-2b/b phenotype at a rate as high as 60%. In contrast, G-CSF–untreated B6D2F1 recipients contained mostly endogenous (H-2b/d) hematopoietic cells.

Hematopoietic Chimerism of Recipient F1 Mice After Parental BM Grafting

| Recipient . | Treatment3-150 . | Donor . | BM Cells3-151 . | Hematopoietic Chimerism3-152 . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | H-2b/b . | H-2b/d . |

| B6D2F1 | None | B6 | 1 × 105 | 6.2% | 91.0% |

| 8.5% | 90.4% | ||||

| 16.5% | 82.4% | ||||

| B6D2F1 | G-CSF | B6 | 1 × 105 | 42.0% | 55.0% |

| 54.0% | 40.3% | ||||

| 60.2% | 38.2% | ||||

| Recipient . | Treatment3-150 . | Donor . | BM Cells3-151 . | Hematopoietic Chimerism3-152 . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | H-2b/b . | H-2b/d . |

| B6D2F1 | None | B6 | 1 × 105 | 6.2% | 91.0% |

| 8.5% | 90.4% | ||||

| 16.5% | 82.4% | ||||

| B6D2F1 | G-CSF | B6 | 1 × 105 | 42.0% | 55.0% |

| 54.0% | 40.3% | ||||

| 60.2% | 38.2% | ||||

G-CSF at 25 μg/kg/d was administered subcutaneously with a miniosmotic pump starting on day −14 and BM cells were grafted on day 0.

Number of T-cell–depleted B6 BM cells transplanted.

Hematopoietic chimerism was examined on day 40. Cells with H-2b/b and H-2b/d phenotypes correspond to donor and recipient, respectively.

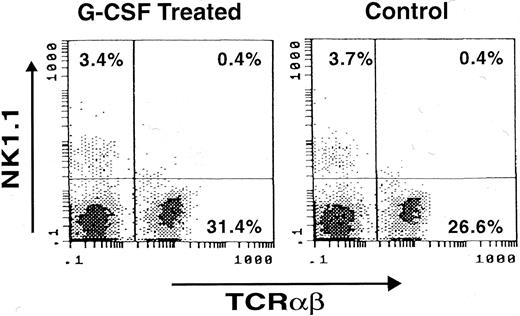

Presence of NK1.1 cells in G-CSF–treated mice.Finally, whether NK cells exist in G-CSF– treated animals was studied. In spleen cells from B6D2F1 mice that had received G-CSF at 25 μg/kg/d for 14 days, TCRαβ− NK1.1+ cells were clearly identified at a frequency (3.4% of the lymphoid cell population) comparable to that of untreated mice (3.7%; Fig 4).

Presence of NK1.1 cells in spleen of mouse treated with G-CSF. A B6D2F1 mouse was treated with G-CSF at 25 μg/kg/d for 14 days with a miniosmotic pump and splenocytes were stained with FITC-labeled anti-TCRαβ antibody (X-axis) and PE-labeled anti-NK1.1 antibody (Y-axis). Note the presence of comparable numbers of NK1.1+ cells in G-CSF–treated and untreated mice (Control).

Presence of NK1.1 cells in spleen of mouse treated with G-CSF. A B6D2F1 mouse was treated with G-CSF at 25 μg/kg/d for 14 days with a miniosmotic pump and splenocytes were stained with FITC-labeled anti-TCRαβ antibody (X-axis) and PE-labeled anti-NK1.1 antibody (Y-axis). Note the presence of comparable numbers of NK1.1+ cells in G-CSF–treated and untreated mice (Control).

DISCUSSION

Pleiotropic actions are a common feature of various cytokines. G-CSF has consistently been shown to exert multiple functions on different cell lineages, but most studies have focused on granulocytic cells and hematopoietic precursors, including very primitive stem cells.20-22 However, attention has recently been directed toward the importance of this cytokine as a regulator of the immune response.7-13

In transplantation medicine, G-CSF has successfully been used to harvest peripheral blood stem cells.2-6 However, grafting of such mobilized stem cells into allogeneic recipients did not increase either the incidence or the severity of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) as compared with allogeneic BM transplantation, despite the presence of significant numbers of mature T cells in the peripheral blood grafts.2,4,6,23-26 The mechanism underlying this observation has not yet been clarified, but the study by Pan et al9 may provide an important clue. Cytokine production of type 1 T cells in response to alloantigens was reduced in mice pretreated with G-CSF, whereas that of type 2 T cells was augmented, suggesting that G-CSF modulates T-cell function so as to promote the type 2 response and thereby reduces the severity of GVHD. Preadministration of G-CSF to donor animals and transplantation of primed splenocytes consistently improved the survival of host animals with experimental GVHD. Using the graft rejection system, we recently showed that expression of G-CSF in recipients, either transgenically or by continuous preadministration, inhibited the rejection of hematopoietic allografts as defined by the appearance of donor-derived splenic colonies, and this was confirmed by a long-term hematopoietic reconstitution study.12 Furthermore, mice transgenic for G-CSF were shown to be excellent recipients even for xenogeneic rat marrow cells.27 These observations show clearly the suppressive effect of G-CSF in various immune responses in which complex mechanisms are operating.

In this report, we present further evidence, in the setting of hybrid resistance,14 15 that G-CSF acts to inhibit host capacity to reject marrow grafts. The mode of action of G-CSF in hybrid resistance is similar to that in our previous observation of allogeneic BM transplantation. Thus, administration of G-CSF to the F1 recipients before parental BM grafting inhibited rejection and induced the appearance of splenic colonies of donor origin. A noteworthy aspect of this study is the importance of preadministration of G-CSF. Little effect was obtained when operation of the G-CSF pumps was started soon after BM grafting, although a weak but significant effect was obtained when G-CSF administration started 1 day before transplantation. In addition, it appears to be critical that recipients be continuously exposed to a certain level of G-CSF because a gradual restoration of the capacity to reject the graft was seen after the G-CSF administration ceased.

G-CSF is a strong promoter of proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic precursors.1 In addition, G-CSF alters the number and the distribution of hematopoietic precursors.28-30 These actions may affect the fate of transplanted precursors. However, this is unlikely for several reasons. The administration of G-CSF soon after BM grafting had little effect on the inhibition of rejection, indicating that the appearance of colonies is not a direct action of G-CSF on grafted colony-forming precursors. To obtain splenic colonies of donor origin, preadministration must be started at least 24 hours before grafting in our system. It is also possible that the altered distribution of hematopoietic precursors influences the mode of appearance of splenic colonies because precursors capable of producing colonies accumulate in the spleen after G-CSF treatment.28-30 The precise mechanism by which G-CSF increases the number of stem cells in the spleen is as yet unknown, but it is possible that precursors in the BM are forced to migrate to the spleen due to the BM cavity being fully occupied by cells induced to undergo maturation by G-CSF. If this is the case, it is conceivable that the grafted precursors are more likely to migrate to the spleen than to BM, thereby increasing the likelifood of homing and proliferating in the splenic microenvironment. However, this possibility was ruled out by the syngeneic combination results. Splenic colony numbers in syngeneic BM transplantation were not influenced by the presence of G-CSF, at least at the dosage of 25 μg/kg/d. From these results, it can surely be concluded that the phenomenon of hybrid resistance inhibition induced by G-CSF is not the result of a hematopoietic-promoting action of G-CSF. However, the possibility remains that any change in the hematopoietic microenvironment induced by the prolonged and dysregulated presence of G-CSF may favor the acceptance of BM grafts that would otherwise be rejected.

Hybrid resistance is an immunologic phenomenon governed by unusual mechanisms.14 B6 BM grafts are vigorously rejected by irradiated (B6xDBA/2)F1 mice, whereas B6 skin grafts are readily accepted by F1 mice. NK cells and certain T cells are considered to be engaged in the rejection process, and molecules other than the T-cell receptor, eg, Ly49 families, appear to mediate this type of allospecificity. Ly49 molecules serve as receptors for class I major histocompatibility complex molecules, each of which exhibits allospecific recognition.31-34 The mechanism by which G-CSF exerts inhibitory effect on hybrid and allogeneic resistance is as yet unknown, but it is possible that this cytokine suppresses a certain step in the recognition and killing process of target cells by effectors. In our preliminary study, splenic NK1.1 cells partially purified from G-CSF–treated mice exhibited sufficient killing activity against YAC1 cells, the prototypic NK-sensitive cells (unpublished observation). However, this observation does not rule out the possibility that NK cell activity is downregulated in the G-CSF–treated host because NK cells are heterogenous and a certain subset of NK cells may be involved in BM graft rejection.31,34 In this regard, the report by Taga et al8 describing NK cells obtained from patients who received G-CSF treatment as showing reduced killing activity and cocultivation with G-CSF–primed neutrophils as decreasing NK cell activity is of interest. These investigators also showed that direct contact between NK cells and primed neutrophils was necessary to downregulate NK cell activity. Whether a similar mechanism operates in our system is now being investigated.

A unique feature of G-CSF–induced suppression of graft rejection in our system is that the effect is transient and reversible. Gradual recovery after the cessation of G-CSF treatment indicates the unlikeliness of an antigen-specific priming effect. Rather, it implies the nonspecific suppression of certain immune responses during the period of upregulated G-CSF level. In this sense, it is noteworthy that allogeneic and xenogeneic BM grafts survived and reconstituted for a long period of time in host mice transgenic for G-CSF. In the hybrid resistance system as well, long-term reconstitution of donor-originated hematopoiesis was shown in this study. These observations suggest that maintenance of G-CSF at an upregulated level in vivo works to decrease host defense mechanisms against certain stimuli.

In conclusion, G-CSF acts to suppress the graft rejection mechanism mediated by complex immunologic responses. This implies a newly recognized role of G-CSF as an immunosuppressive reagent. G-CSF has been extensively used clinically and numerous studies have been performed on its effect on hematopoiesis. The results described herein underscore the importance of this cytokine as an immunomodulator in various situations. Further study is anticipated to provide new strategies aimed at manipulating the immune response in various clinical settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank J. Satoh and M. Sone for their excellent animal care and secretarial work, respectively.

Supported in part by a Grant for Pediatric Research (6C-01, 6C-05) and a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research (5-24) from the Ministry of Health and Welfare and by funds provided by the Entrustment of Research Programme of the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research in Japan.

Address reprint requests to Junichiro Fujimoto, MD, Department of Pathology, National Children's Medical Research Center, 3-35-31 Taishido, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 154, Japan.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal