Abstract

Neutrophils play a key role in the pathophysiology of septic multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) through excessive release of toxic granule components and reactive oxygen metabolites with consequent tissue destruction. The increase of senescent neutrophils during sepsis indicates a potential breakdown of autoregulatory mechanisms including apoptotic processes to remove activated neutrophils from inflammatory sites. Therefore, neutrophil apoptosis of patients with severe sepsis and its regulatory mechanisms were investigated. Spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis from patients with severe sepsis was significantly reduced in comparison to healthy individuals. Cytokines detected in the circulation during sepsis (tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], interferon-γ [IFN-γ], granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF], granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF]) inhibited neutrophil apoptosis in both groups, though the effect was more distinct in neutrophils from healthy humans. Addition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to neutrophils from healthy humans markedly (P < .05) reduced apoptosis which was partially restored through addition of anti–TNF-antibody. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) counteracted (P < .05) inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis induced by LPS, recombinant human (rh) TNF-α, rhIFN-γ, rhG-CSF, and rhGM-CSF, whereas rhIL-4 or rhIL-13 were ineffective. Reduced neutrophil apoptosis during sepsis was concomitant with increased tyrosine phosphorylation, while IL-10 markedly inhibited tyrosine phosphorylation in LPS-stimulated neutrophils. These results identify proinflammatory cytokines and IL-10 as strong regulators of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis during sepsis. Inhibition as well as acceleration of neutrophil apoptosis seems to be associated with alterations of signal transduction pathways.

PROGRAMMED CELL DEATH (apoptosis) represents a physiological clearance mechanism in the circulation and in tissue to maintain homeostasis of leukocyte numbers in healthy humans.1 In the case of mature human neutrophils this is achieved through rapid spontaneous apoptosis within hours. During sepsis, marked alterations of the differential blood cell count such as a significant increase in the number of neutrophils have been observed. In acute inflammation, this seems to represent a physiologic and beneficial host response, because neutrophils, with their metabolites, play a key role in the elimination of invading microorganisms. However, there is evidence that chronic release of toxic products can result in severe tissue injury at sites of inflammation.2,3 Apoptosis, besides other mechanisms (exhaustion of secretory capacity and of internal energy supplies, receptor downregulation), regulates and terminates neutrophil efficacy.4 5 Thus, prolonged neutrophil survival during sepsis can cause a dysbalanced tissue load of neutrophils and uncontrolled release of toxic metabolites.

Apoptosis of neutrophils from healthy humans can be downregulated by proinflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and interleukin-2 (IL-2).6-10 The inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis through these mediators does not only increase life span of cultured neutrophils, but also prolonges their functional longevity assessed by a number of parameters including secretion of toxic products.10

The pathophysiological mechanisms of extended life span of neutrophils during sepsis have been poorly described. Since secretion of proinflammatory cytokines is significantly increased during septic episodes,11-18 these mediators may be involved in apoptotic processes that lead to elimination of senescent neutrophils. In addition, recent studies clearly showed that tyrosine phosphorylation is implicated in the regulation of apoptosis.19,20 Because lipopolysaccharide (LPS) upregulates tyrosine phosphorylation,21 while IL-10 strongly inhibits tyrosine kinase activity,21 altered neutrophil apoptosis may be due to an acceleration or an inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation. In the present study we examine spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils from patients with severe sepsis compared to those from healthy humans. Furthermore, the influence of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators on neutrophil apoptosis and the role of altered tyrosine phosphorylation were determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Special reagents.The following reagents were obtained from commercial sources: Propidium iodide (PI), LPS Escherichia coli 055:B5, phenylarsine oxide (PAO) (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO); recombinant human (rh) IL-1β (biological activity, 1.0 × 108 U/mg), IL-2 (biological activity, 2.4 × 106 U/mg), IL-4 (biological activity, 1.0 × 107 U/mg), IL-6 (biological activity, 1.0 × 108 U/mg), IL-8, TNF-α (biological activity, 1.0 × 107 U/mg) (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA); murine monoclonal antibody (MoAb) antihuman TNF-α (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA); murine MoAb antiphosphotyrosine (P-Tyr) 4G10 (Biomol, Hamburg, Germany); goat-antimouse IgG conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Immunotech, Marseille, France). Recombinant human IFN-γ (biological activity, 3.0 × 107 U/mg), IL-10 (biological activity, 1.0 × 107 U/mg), IL-12p70 (biological activity, 4.1 × 108 U/mg), and IL-13 were provided as gifts from Dr G.R. Adolf (IFN-γ, Bender, Wien, Austria), Dr S. Narula (IL-10; Schering Plough, Kenilworth, NJ), Dr M. Gately (IL-12p70; Hoffmann-LaRoche, Nutley, CA), and Dr A. Minty (IL-13; Sanofi Recherche, Labège Cedex, France). Recombinant human (rh) G-CSF (biological activity, 1.0 × 108 U/mg) and GM-CSF (biological activity, 11.1 × 106 U/mg) were gifts from Dr F.R. Seiler (Behring, Marburg, Germany). The endotoxin contamination of recombinant cytokines was negligible (<10 EU/mg protein in the limulus assay).

Patient selection.Heparinized blood was obtained from 6 patients with severe sepsis which was compared to that of 6 healthy volunteers. Sepsis was defined according to the criteria of Bone et al.22 Infection was due to pneumonia (n = 3), and wound infection after severe burn injury (n = 3). The group of healthy individuals was comparable to that of septic patients with regard to age and sex. All patients were enrolled into this study under informed consent guidelines approved by the Human Ethical Committee of the University of Zurich.

Preparation and culture conditions of purified neutrophils.Whole blood from patients was taken during the first 24 hours after diagnosis of severe sepsis. Heparinized blood (20 U heparin/mL; heparin was tested for endotoxin: <5 pg/mL heparin) from either group was diluted 1:1 with RPMI 1640 medium. Neutrophils were isolated by centrifugation in Histopaque-1077 (Sigma Chemical Co) followed by two washing steps in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysis of erythrocytes using 9 vol of an ice-cold isotonic ammonium chloride solution (NH4Cl 155 mmol/L, KHCO3 10 mmol/L, and EDTA 0.1 mmol/L) to 1 vol of cell pellet at 0°C for 7 minutes.19 The preparation contained greater than 95% neutrophils as was determined by flow cytometry analysis using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled MoAb anti-CD15 (Coulter, Hialeah, FL). Cell viability was greater than 98% using trypan blue exclusion. Isolated neutrophils were maintained in RPMI 1640-medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; GIBCO-BRL, Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 1.5 mmol/l L-Glutamax (GIBCO-BRL) at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL in 24-well cell-culture clusters (Costar Co, Cambridge, MA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2). Isolated neutrophils were incubated with or without various proinflammatory mediators rhIL-1β (2.5 ng/mL), rhIL-2 (20 ng/mL), rhIL-6 (1,000 U/mL), rhIL-8 (20 ng/mL), rhIL-12p70 (20 ng/mL), rhTNF-α (1,000 U/mL), rhIFN-γ (10 ng/mL), rhG-CSF (10 ng/mL), and rhGM-CSF (10 ng/mL) for 16 hours. Additionally, the effect of anti-inflammatory reacting cytokines (rhIL-4 [50 ng/mL], rhIL-10 [100 U/mL], rhIL-13 [50 ng/mL]) was tested on neutrophil apoptosis in the presence or absence of LPS (1 μg/mL). Furthermore, LPS-stimulated neutrophils were coincubated with anti–TNF-α-MoAb (10 μg/mL). The cell loss in neutrophil cultures was less than 5% irrespective of the experimental design or the added proteins using microscopic cell counting.

Analysis of apoptotic cellular morphology of neutrophils.For analysis of apoptotic morphology, cytospin preparations of neutrophils were treated with a commercially available kit for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) technique (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. In brief, air-dried cytospin preparations were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution, rinsed with PBS, and incubated in permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate) for 5 minutes on ice. The slides were again rinsed with PBS, and incubated with TUNEL reaction mixture (TdT, FITC-labeled nucleotides) for 1 hour in a humidified chamber. The slides were mounted in 50% glycerol/PBS and examined on a fluorescence microscope (Leica Dialux 22 EB; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The typical morphologic changes of apoptosis in neutrophils consist of diminution in cell volume and chromatin condensation yielding fragmented or bright homogeneously fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-stained nuclei.10 Five hundred cells were counted per slide, and data were reported as the percentage of apoptotic cells.

Quantitation of DNA fragmentation.Neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) were washed in sample buffer (PBS containing glucose [1 g/L]). Cells were fixed in 1 mL of 70% ethanol over 12 hours at 4°C. Fixed cells were incubated in 1 mL propidium iodide staining solution (sample buffer with 50 μg/mL propidium iodide [PI] and 100 U/mL RNase A [Boehringer]) at room temperature. PI fluorescence of individual nuclei was measured using an Epics Profile flow cytometer (Coulter), while gating on physical parameters to exclude cell debris. A minimum of 10,000 events was counted per sample. Results are reported as the percentage of hypodiploid (fragmented) nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic cells.23

Cytokine measurements in serum and culture supernatant.TNF-α and IL-1β in supernatant were measured with specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) using the antihuman TNF-α MoAb 2TNF-H22 and antihuman IL-1β MoAb ILB1-H6 for capture, and antihuman TNF-α MoAb 2TNF-H34 and antihuman IL-1β MoAb ILB1-H67 for detection (kindly provided by Dr J. Kenney, Syntex Inc, Palo Alto, CA). For standards, rhTNF-α and rhIL-1β (Genzyme) were used. The sensitivity of the ELISA was 10 pg/mL and 15 pg/mL, respectively. Furthermore, IFN-γ, G-CSF, and GM-CSF in supernatants were measured by commercially available ELISA with a sensitivity of greater than 20 pg/mL for IFN-γ and 10 pg/mL for G-CSF or GM-CSF (IFN-γ ELISA: Genzyme; G-CSF ELISA: Pharmingen, Hamburg, Germany; GM-CSF ELISA: R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany). IL-10 in supernatants was measured by ELISA with the rat-antihuman IL-10 MoAb JES3-9D7 for capture and a rabbit-antihuman IL-10 polyclonal antibody for detection (antibodies kindly provided by S. Narula, Schering-Plough). Recombinant human IL-10 (Schering-Plough) diluted in normal plasma was used for the standard curve. The ELISA showed a sensitivity of greater than 20 pg/mL. All samples were tested in duplicate.

Detection of tyrosine phosphorylation by flow cytometry.The amount of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in neutrophils was analyzed by flow cytometry. Briefly, 1 × 106 neutrophils from healthy individuals and patients with severe sepsis were stimulated with or without 10 μmol/L PAO for 30 minutes at 37°C. The treatment of the cells with PAO acts as positive control increasing levels of tyrosine phosphorylation by inhibition of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase.19 Furthermore, cells from healthy volunteers were incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) for 2 hours at 37°C. Cells were washed in PBS containing 2 mmol/L vanadate (Sigma) and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde solution for 10 minutes at room temperature. After a washing step in PBS supplemented with vanadate, cells were resuspended in staining solution for permeabilization of cell membrane (PBS containing saponin (0.5 mg/mL), 1% BSA, and 2 mmol/L vanadate). Thereafter, cells were incubated with the antiphosphotyrosine-MoAb (P-Tyr) for 60 minutes at room temperature. After an additional washing step with staining solution, cells were incubated with goat-antimouse IgG-FITC for 30 minutes at room temperature. After two washes, cells were resuspended in 300 μL of staining solution and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.19

Data analysis.Results are demonstrated as mean ± SEM. Mean values were compared using Student two-tailed t-test for independent means. Differences were regarded as significant, if P < .05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

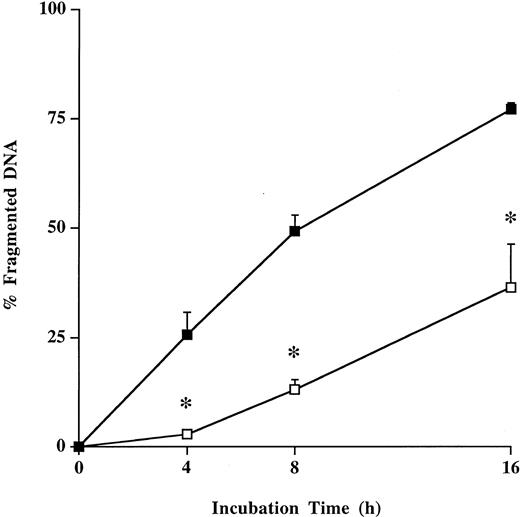

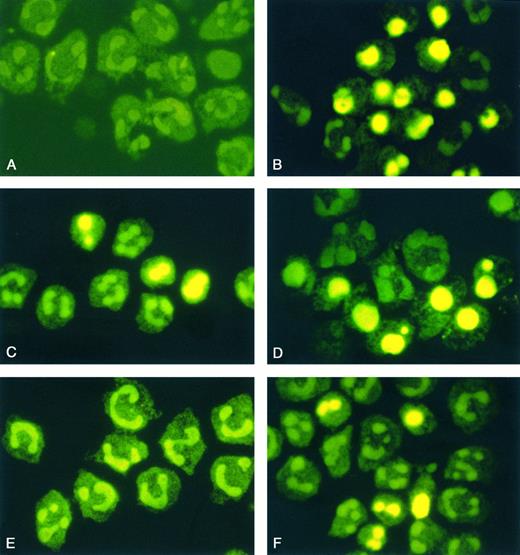

Spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils.The spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils from patients with severe sepsis was significantly (P < .05) decreased during the entire incubation period compared with neutrophils from healthy humans using quantitative flow cytometry analysis of PI-stained nuclei (Fig 1). These results were confirmed morphologically on cytospin preparations by TUNEL method (Fig 2A, B, E, F). Freshly isolated neutrophils from healthy individuals and from septic patients did not show apoptotic morphological features (Fig 2A, E). However, typical apoptotic morphological features were detected in neutrophils from healthy individuals after 4 hours (10.1% ± 1.5%), 8 hours (25.0% ± 4.8%), and 16 hours (74.1% ± 4.4%) of incubation (Fig 2B). In contrast, neutrophils from patients with severe sepsis demonstrated a marked (P < .05) reduction of apoptotic neutrophils after 4 hours (3.0% ± 0.5%), 8 hours (12.5% ± 2.5%), and 16 hours (32.3% ± 4.7%) of incubation (Fig 2F).

Spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils from healthy humans and patients with severe sepsis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy volunteers (control; ▪) and patients with severe sepsis (patient; □) were incubated for 16 hours. Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with propidium iodide. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic cells. Results represent the mean ± SE of six separate experiments performed with neutrophils from healthy volunteers and patients with sepsis. *P < .05 septic patients versus healthy volunteers.

Spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils from healthy humans and patients with severe sepsis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy volunteers (control; ▪) and patients with severe sepsis (patient; □) were incubated for 16 hours. Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with propidium iodide. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic cells. Results represent the mean ± SE of six separate experiments performed with neutrophils from healthy volunteers and patients with sepsis. *P < .05 septic patients versus healthy volunteers.

Morphological features of neutrophil apoptosis. Cytospin preparations of neutrophils from healthy volunteers (A through D) and from patients with severe sepsis (E and F) were treated with TUNEL method after 0 hours (A and E) and 16 hours of incubation (B and F). In addition, neutrophils of healthy humans were incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) or coincubated with LPS and rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) (C and D). The typical morphologic changes of apoptosis consist of diminution in cell volume and chromatin condensation yielding fragmented or bright homogeneously FITC-stained nuclei. Original magnification of the figures: × 1,000. The figures are representative of five other experiments that yielded the same results.

Morphological features of neutrophil apoptosis. Cytospin preparations of neutrophils from healthy volunteers (A through D) and from patients with severe sepsis (E and F) were treated with TUNEL method after 0 hours (A and E) and 16 hours of incubation (B and F). In addition, neutrophils of healthy humans were incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) or coincubated with LPS and rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) (C and D). The typical morphologic changes of apoptosis consist of diminution in cell volume and chromatin condensation yielding fragmented or bright homogeneously FITC-stained nuclei. Original magnification of the figures: × 1,000. The figures are representative of five other experiments that yielded the same results.

Effect of proinflammatory cytokines on neutrophil apoptosis.Because synthesis and release of proinflammatory cytokines are increased during sepsis,11-18 the influence of these mediators on neutrophil apoptosis was investigated in healthy individuals and in patients with severe sepsis. Concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines were chosen according to the levels detected in the circulation of septic patients (TNF-α: range, 10 to 1,330 U/mL,11 IL-1β: range, 150 to 2,920 pg/mL,12 IL-6: range, 100 to 135,000 pg/mL,13 IL-8: range, 168 to 30,000 pg/mL,14 IFN-γ: 1,400 ± 4,000 pg/mL (mean ± SD),16 G-CSF: range, 10 to 700 ng/mL,18 GM-CSF: range, 1 to 15 ng/mL.18 Although a comparison between in vitro experiments and the in vivo situation has to be drawn carefully, the use of clinically relevant concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines provides further information about their regulatory role in neutrophil apoptosis during clinical sepsis. Furthermore, most of the doses of proinflammatory cytokines used are similar to those used in previous in vitro studies dealing with neutrophil apoptosis.6-10

Recombinant human TNF-α, rhIFN-γ, rhG-CSF, and rhGM-CSF exerted the strongest effects on neutrophil apoptosis with a significant (P < .05) reduction of spontaneous DNA fragmentation in neutrophils from healthy humans by −57%, −57%, −55%, and −61%, respectively (Fig 3). A similar response was observed in neutrophils from patients with severe sepsis, although this effect was less distinct (Fig 3). rhIL-1β, rhIL-2, and rhIL-12p70 exclusively reduced spontaneous apoptosis of normal neutrophils without affecting apoptosis of neutrophils from septic patients (Fig 3). rhIL-6 and rhIL-8 were ineffective in both groups (Fig 3).

Influence of proinflammatory cytokines on neutrophil apoptosis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans (control; ▪), and patients with severe sepsis (patient; □), were incubated during 16 hours with various recombinant human proinflammatory cytokines: IL-1β (2.5 ng/mL), IL-2 (20 ng/mL), IL-6 (1,000 U/mL), IL-8 (20 ng/mL), IL-12p70 (20 ng/mL), TNF-α (1,000 U/mL), IFN-γ (10 ng/mL), G-CSF (10 ng/mL), GM-CSF (10 ng/mL). Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with propidium iodide. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic cells. Results represent the mean ± SEM of five separate experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from five independent healthy individuals and five patients with severe sepsis. *P < .05 cytokine-treated versus untreated cells.

Influence of proinflammatory cytokines on neutrophil apoptosis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans (control; ▪), and patients with severe sepsis (patient; □), were incubated during 16 hours with various recombinant human proinflammatory cytokines: IL-1β (2.5 ng/mL), IL-2 (20 ng/mL), IL-6 (1,000 U/mL), IL-8 (20 ng/mL), IL-12p70 (20 ng/mL), TNF-α (1,000 U/mL), IFN-γ (10 ng/mL), G-CSF (10 ng/mL), GM-CSF (10 ng/mL). Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with propidium iodide. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic cells. Results represent the mean ± SEM of five separate experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from five independent healthy individuals and five patients with severe sepsis. *P < .05 cytokine-treated versus untreated cells.

These results confirm the regulatory role of proinflammatory cytokines on spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis, as has been shown in most of the recent studies using neutrophils from healthy humans.6-10 However, our results are different from observations of Takeda et al24 and Tsuchida et al.25 They found an increased apoptosis of human and rat neutrophils after incubation with various concentrations of rhTNF-α. Although both studies are from the same group, they are contradictory. Tsuchida et al25 described a dose-dependent increase of neutrophil apoptosis from 2% (control) to 5% and 11% with 100 U/mL and 1,000 U/mL rhTNF-α, respectively. Low doses of rhTNF-α (1, 10 U/mL) were ineffective in their study. In contrast, Takeda et al24 found an enhanced neutrophil apoptosis from 5% (control) to 20% using 10 U/mL rhTNF-α, but they did not perform a statistical analysis of their data. The rhTNF-α–induced increase of apoptosis from 2% to 5% (100 U/mL rhTNF-α) and 11% (1,000 U/mL rhTNF-α), which was suggested by Tsuchida et al25 to be significant, may be more due to variations between the three performed experiments, rather than to a biological effect of rhTNF-α. Finally, their results are in opposite to previous findings26 27 that rhTNF-α activates neutrophil functions, while our results clearly support these observations. Furthermore, a reduction of total neutrophil numbers under our experimental conditions as a possible explanation for the apoptosis inhibiting effect of TNF-α observed in this study was excluded, because the cell loss during the incubation time of 16 hours was less than 5%.

In contrast to healthy humans, apoptosis of neutrophils from septic patients could only be slightly inhibited by proinflammatory cytokines. This indicates a decreased sensitivity of neutrophils to apoptosis downregulating cytokines during severe infection. It can be speculated that this effect may be due to early contact of neutrophils from septic patients with circulating proinflammatory cytokines in vivo.11-18 In this context, preliminary experiments indicate that serum obtained from patients with severe sepsis can sustain the survival of neutrophils from healthy individuals. In contrast, serum from healthy individuals was only slightly effective in increasing the life span of autologous freshly isolated neutrophils.

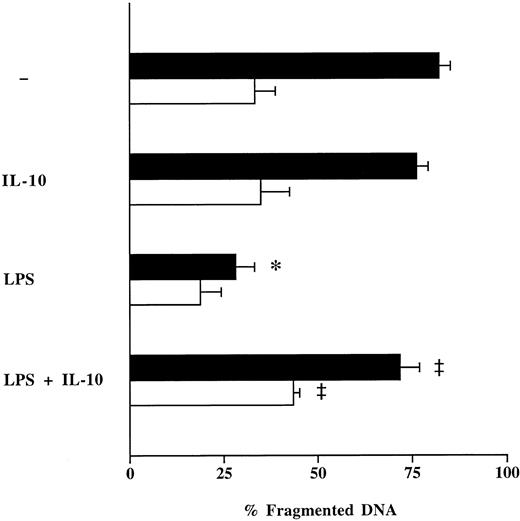

Effect of LPS on neutrophil apoptosis and influence of anti-inflammatory cytokines.To imitate the clinical scenario of sepsis in vitro, isolated neutrophils from healthy individuals were incubated with LPS. LPS markedly (P < .05) reduced spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils from healthy volunteers by −54%, while it only slightly influenced neutrophil apoptosis in septic patients (−15%) (Fig 4). The inhibitory effect of LPS on neutrophil apoptosis in both groups could be significantly decreased by coincubation with clinically relevant concentrations of rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) (Fig 4).28,29 In contrast, rhIL-4 (50 ng/mL) and rhIL-13 (50 ng/mL) were ineffective (data not shown). These results were confirmed by TUNEL method on cytospin preparations of neutrophils from healthy individuals (Fig 2 B through D). The apoptosis inhibiting effect of LPS, which corresponds with previous studies,6,10,30 may represent an autoprotective mechanism of the host to increase the defense response to invasion of microorganisms and their cell components. Regarding the effect of IL-10 on the apoptosis of neutrophils stimulated with LPS, our results are in accordance with previous studies from Cox.30 He demonstrated similar effects of IL-10 on apoptosis of lung neutrophils in vivo in a rat model of LPS-induced lung injury and on LPS-stimulated human peripheral blood neutrophils in vitro.

Effect of rhIL-10 on LPS-induced suppression of neutrophil apoptosis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans (control; ▪) and patients with severe sepsis (patient; □) were cultured with LPS (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) for 16 hours. Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with propidium iodide. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic neutrophils. Results represent the mean ± SEM of five separate experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from five independent healthy individuals and five patients with severe sepsis. *P < .05 without agent versus LPS; ‡P < .05 without rhIL-10 versus with rhIL-10.

Effect of rhIL-10 on LPS-induced suppression of neutrophil apoptosis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans (control; ▪) and patients with severe sepsis (patient; □) were cultured with LPS (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) for 16 hours. Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with propidium iodide. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic neutrophils. Results represent the mean ± SEM of five separate experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from five independent healthy individuals and five patients with severe sepsis. *P < .05 without agent versus LPS; ‡P < .05 without rhIL-10 versus with rhIL-10.

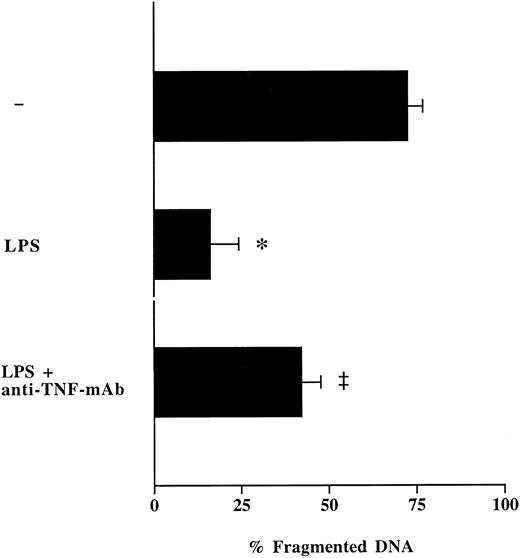

Influence of anti–TNF-antibodies on LPS-modulated neutrophil apoptosis.To test whether LPS inhibits spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis through synthesis and release of TNF-α, neutrophils from healthy volunteers were cultured with LPS in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti–TNF-α-MoAb. Measurements of TNF-α levels in neutrophil supernatants showed a complete neutralization of secreted TNF-α through the addition of anti–TNF-α-MoAb. The presence of anti–TNF-α-MoAb in neutrophil cultures partially abrogated the inhibitory effect of LPS on neutrophil apoptosis (Fig 5). These data lead us to conclude that LPS-induced release of TNF-α by neutrophils is at least, in part, responsible for increased survival of neutrophils after contact with LPS. Thus, during inflammation, neutrophils can regulate their own apoptosis in an autocrine fashion through secretion of proinflammatory cytokines.31 32

Effect of anti–TNF-α-MoAb on LPS-induced suppression of neutrophil apoptosis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans were cultured with LPS (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti–TNF-α-antibodies (10 μg/mL) during 16 hours. Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with propidium iodide. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic cells. Results represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from three different healthy individuals. *P < .05 without agent versus LPS; ‡P < .05 without anti–TNF-α-MoAb versus with anti–TNF-α-MoAb.

Effect of anti–TNF-α-MoAb on LPS-induced suppression of neutrophil apoptosis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans were cultured with LPS (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti–TNF-α-antibodies (10 μg/mL) during 16 hours. Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with propidium iodide. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic cells. Results represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from three different healthy individuals. *P < .05 without agent versus LPS; ‡P < .05 without anti–TNF-α-MoAb versus with anti–TNF-α-MoAb.

Effect of rhIL-10 on neutrophil apoptosis modulated through proinflammatory cytokines.Proinflammatory cytokines, added as recombinant proteins to neutrophil cultures, have been shown to delay spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils maintained in vitro (Figs 3-5), while coincubation of LPS-stimulated neutrophils with IL-10 increased apoptosis of these cells. The inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis after stimulation with LPS may be due to secretion of apoptosis blocking cytokines by neutrophils themselves.31,32 Neutrophils secrete after stimulation with LPS some of the proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) which have been found to reduce their apoptosis (Table 1). In contrast, other mediators (IFN-γ, G-CSF, GM-CSF), despite their potency to extend neutrophil life span, have not been detected in supernatants of LPS-stimulated neutrophils during 16 hours of incubation, even when using high cell concentrations (5 × 106 neutrophils/mL). Previous studies have reported that neutrophils secrete low amounts of G-CSF,31-33 although mostly PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) was used for stimulation of neutrophils.31,32 The difference between the study of Ichinose et al33 and our study seems to be due to different incubation times (24 hours v 16 hours). After incubating neutrophils for 24 hours we also detected G-CSF in low amounts in supernatants of LPS-stimulated neutrophils (data not shown).

Cytokine Secretion of Neutrophils

| . | — . | LPS . | LPS + rhIL-10 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | ND | 39.8 ± 6.6* | 13.4 ± 5.5† |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | ND | 69.0 ± 28.8* | ND |

| . | — . | LPS . | LPS + rhIL-10 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | ND | 39.8 ± 6.6* | 13.4 ± 5.5† |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | ND | 69.0 ± 28.8* | ND |

Isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy individuals were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) for 16 hours. Concentrations of cytokines were measured by specific ELISA. IFN-γ, G-CSF, GM-CSF, and IL-10 were not detectable. The data represent the mean ± SEM for five separate experiments.

Abbreviation: ND, not detectable.

P < .05 without agent v LPS.

P < .05 without rhIL-10 v with rhIL-10.

The addition of rhIL-10 attenuated LPS-induced release of apoptosis blocking cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β (Table 1).34 This suggests that the inhibiting effect of IL-10 on neutrophil apoptosis, after coincubation with LPS, may be due to the blockage of neutrophil proinflammatory cytokine release. Because IL-10 was not detected in supernatants of LPS-stimulated neutrophils, the apoptosis-enhancing effect of IL-10 seems to occur in a paracrine way.

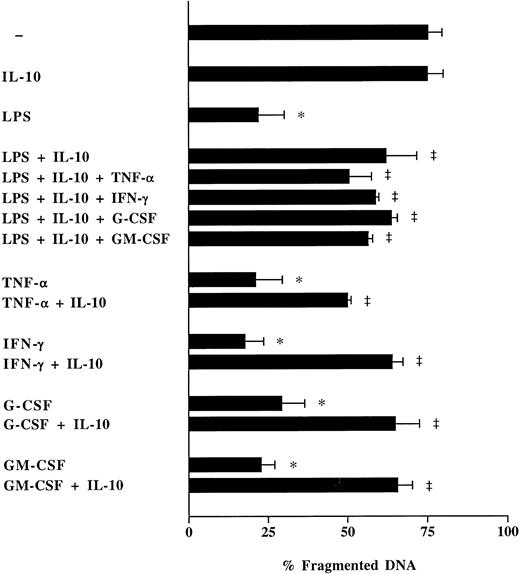

To study whether the apoptosis inducing effect of rhIL-10 can be reversed, various recombinant proinflammatory cytokines were added to neutrophil cultures from healthy humans coincubated with LPS and IL-10 (Fig 6). Neither rhTNF-α, nor rhIFN-γ, rhG-CSF, or rhGM-CSF were able to counterregulate the effect of IL-10 on apoptosis of LPS-stimulated neutrophils (Fig 6). Moreover, the reduction of neutrophil apoptosis through proinflammatory cytokines could be attenuated through addition of rhIL-10 (Fig 6). Thus, recombinant human IL-10 may irreversibly interfere with the intracellular responses to external stimuli through blockage of signaling pathways rather than through an indirect effect via inhibition of apoptosis reducing proinflammatory cytokines.

Effect of rhIL-10 on neutrophil apoptosis modulated through LPS and/or proinflammatory cytokines. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans were cultured with rhTNF-α (1,000 U/mL), rhIFN-γ (10 ng/mL), rhG-CSF (10 ng/mL), or rhGM-CSF (10 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) and LPS (1 μg/mL) for 16 hours. Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with PI. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic cells. Results in each figure represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from three different healthy individuals. *P < .05 without agent versus LPS/rhTFN-α/rhIFN-γ/rhG-CSF/rhGM-CSF; ‡P < .05 without rhIL-10 versus with rhIL-10.

Effect of rhIL-10 on neutrophil apoptosis modulated through LPS and/or proinflammatory cytokines. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans were cultured with rhTNF-α (1,000 U/mL), rhIFN-γ (10 ng/mL), rhG-CSF (10 ng/mL), or rhGM-CSF (10 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) and LPS (1 μg/mL) for 16 hours. Neutrophil apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with ethanol and staining with PI. Data are reported as the percentage of fragmented nuclei reflecting the relative proportion of apoptotic cells. Results in each figure represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments performed with neutrophils isolated from three different healthy individuals. *P < .05 without agent versus LPS/rhTFN-α/rhIFN-γ/rhG-CSF/rhGM-CSF; ‡P < .05 without rhIL-10 versus with rhIL-10.

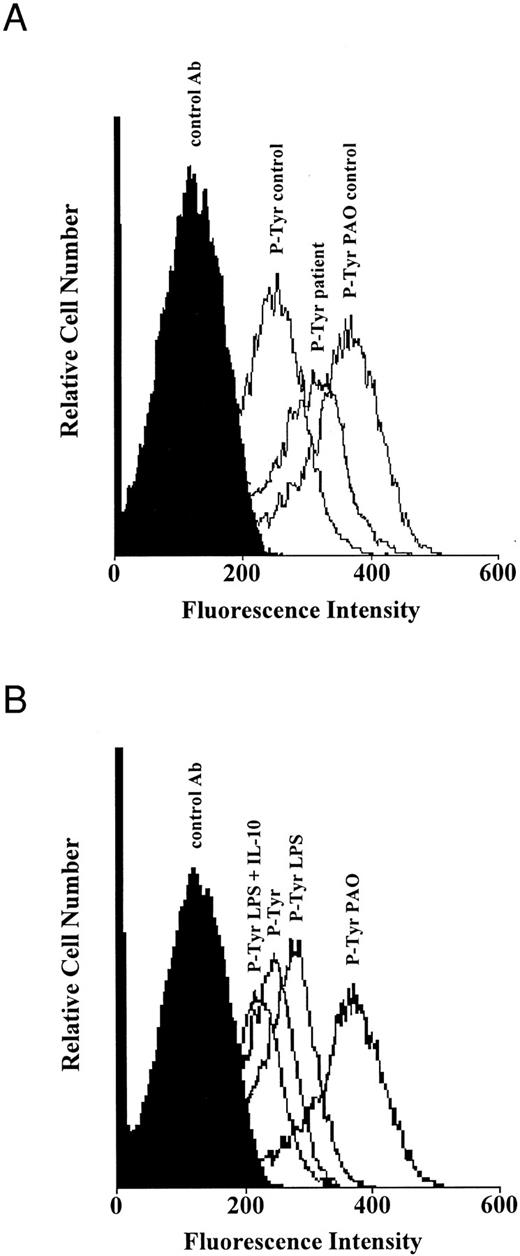

Role of tyrosine phosphorylation in neutrophil apoptosis.Previous studies emphasized a pivotal role of tyrosine kinases in the regulation of apoptosis.19,20 Upregulation of tyrosine phosphorylation in eosinophils and neutrophils through proinflammatory cytokines protected these cells from spontaneous apoptosis.19 Because IL-10 predominantly interferes with protein tyrosine kinases,21 alterations of tyrosine phosphorylation may account for the acceleration of neutrophil apoptosis through IL-10. Tyrosine phosphorylation was increased in neutrophils from septic patients compared with that in neutrophils from healthy humans (Fig 7A). Stimulation of neutrophils with LPS increased tyrosine phosphorylation in neutrophils from healthy humans compared to untreated neutrophils, while coincubation with IL-10 prevented the increase of tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig 7B). Incubation of neutrophils with the protein-tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor PAO led to a strong increase of tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig 7A and B), which confirms the accuracy of the technique used for measurements of tyrosine phosphorylation. Thus, protein tyrosine phosphorylation seems to play a key role in the regulation of neutrophil apoptosis, which is in line with previous studies.19 20 These results further suggest that inhibition and acceleration of neutrophil apoptosis is associated with alterations of the signal transduction pathways.

Tyrosine phosphorylation in neutrophils from healthy individuals and patients with severe sepsis. (A) Increased tyrosine phosphorylation in neutrophils from patients with sepsis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans (control) and patients with severe sepsis (patient) were cultured with or without the protein-tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor phenylarsine oxide (PAO; 10 μmol/L) for 30 minutes at 37°C. (B) Inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation in normal neutrophils by IL-10. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans were cultured with or without LPS (1 μg/mL) and rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) for 2 hours at 37°C. Levels of tyrosine phosphorylation were analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with saponin and staining with antiphosphotyrosine (P-Tyr) and goat-antimouse FITC-conjugated antibodies. Both figures are representative of three other experiments that yielded the same results.

Tyrosine phosphorylation in neutrophils from healthy individuals and patients with severe sepsis. (A) Increased tyrosine phosphorylation in neutrophils from patients with sepsis. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans (control) and patients with severe sepsis (patient) were cultured with or without the protein-tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor phenylarsine oxide (PAO; 10 μmol/L) for 30 minutes at 37°C. (B) Inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation in normal neutrophils by IL-10. Freshly isolated neutrophils (1 × 106/mL) from healthy humans were cultured with or without LPS (1 μg/mL) and rhIL-10 (100 U/mL) for 2 hours at 37°C. Levels of tyrosine phosphorylation were analyzed by flow cytometry after permeabilization with saponin and staining with antiphosphotyrosine (P-Tyr) and goat-antimouse FITC-conjugated antibodies. Both figures are representative of three other experiments that yielded the same results.

In conclusion, the spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils is markedly reduced during severe infection compared with that of healthy individuals. The prolonged survival of neutrophils may at least partly represent the underlying mechanism that causes granulocytosis seen during septic episodes. Proinflammatory cytokines, secreted after contact of macrophages and neutrophils with LPS, majorly contribute to the inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis in an autocrine and/or a paracrine manner. However, we cannot exclude from this study, that the increased release of juvenile granulocytes from the bone marrow, seen during sepsis, may partially contribute to prolonged survival of neutrophils. IL-10, in contrast to other anti-inflammatory mediators, counteracts decreased neutrophil apoptosis which seems to be regulated through alterations of signal transduction pathways such as tyrosine phosphorylation.

Neutrophils represent an essential line of defense against invading microorganisms. Their efficacy depends on neutrophil adhesion to vascular endothelium, migration into tissues, the release of proteolytic enzymes and reactive oxygen metabolites, as well as their deactivation when the initiating antigen has been destroyed. Furthermore, the regulation of neutrophil survival, which is under the control of a complex network of circulating and local signals, represents an important factor for neutrophil efficacy. There is evidence from our data that decreased apoptosis of neutrophils may reflect one of several autoprotective mechanisms of the host to increase the capacity of the phagocytic host defense to kill and eliminate invading microorganisms. Nevertheless, if host regulatory mechanisms fail or inflammatory stimuli are chronically directed against host tissue, inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis may contribute to self-destruction of host tissues.

Supported by Grant No. 32-43320.95 from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Address correspondence to Wolfgang Ertel, MD, Division of Trauma Surgery, University Hospital Zurich, Raemistrasse 100, CH-8091 Zurich, Switzerland.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal