Abstract

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), a severe complication of heparin treatment, can be associated with new thrombotic complications. HIT antibodies activate platelets via the platelet Fcγ-receptor (FcγRIIa), which carries a functionally relevant polymorphism (FcγRIIa-R-H131). The effect of this polymorphism on the clinical manifestations of HIT is controversial. We determined prospectively the FcγRIIa-R-H131 genotypes in 389 HIT patients, in 351 patients with thrombocytopenia or thrombosis due to causes other than HIT and without detectable HIT antibodies, and in 256 healthy blood donors. For this purpose, a novel nested sequence-specific primer-polymerase chain reaction (SSP-PCR) was developed. FcγRIIa-R/R131 was found to be overrepresented in the HIT patients (27%) compared with the control groups (non-HIT patients [21%] and blood donors [20%]). In a subgroup of 122 well-characterized HIT patients, the genotype distribution in patients presenting with thrombocytopenia only was compared with that of patients who developed thromboembolic complications. The frequency of FcγRIIa-R/R131 among patients with thrombotic events was significantly elevated (37% v 17%;P = .036). Our results indicate that genotype distribution can be correlated to the clinical outcome of patients with HIT. We speculate that the reduced clearance of immune complexes in patients with the FcγRIIa-R/R131 allotype causes prolonged activation of endothelial cells and platelets, thus increasing the risk for thrombotic complications.

© 1998 by The American Society of Hematology.

HEPARIN-INDUCED thrombocytopenia (HIT) is the most common drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. Heparin treatment can induce antibodies that recognize a complex of heparin and platelet proteins, in most cases platelet factor 4 (PF4).1-5 These immune complexes activate platelets and possibly also endothelial cells.2,4,6 Paradoxically, HIT patients are at high risk of developing new venous or arterial thromboembolic vessel occlusions in response to the anticoagulant, heparin. It is now widely accepted that there is a discrepancy between the number of patients who develop HIT antibodies and the number of patients who develop clinical symptoms of HIT (ie, a decrease in platelet counts of >50% on or after day 5 of heparin treatment and/or new thromboembolic complications [TECs]).5,7-9 However, why some HIT patients develop thrombocytopenia only and others develop concomitant TECs remains controversial. In clinically symptomatic patients, platelet activation10 and generation of platelet microparticles11 seem to be important triggers for the development of TECs. Both are mediated by the platelet FcγRIIa,12-14 which, after cross-linking by the heparin/PF4-HIT antibody immune complexes, initiates platelet activation.

The FcγRIIa is the only IgG Fc-receptor present on platelets and the gene encoding the receptor is polymorphic. A point mutation (G507A) causes an amino acid exchange, Arg (R)-His (H) at position 131.15,16 FcγRIIa-R/R131 interacts well with mouse IgG1, and was originally named high responder (HR), whereas FcγRIIa-H/H131 binds mouse IgG1 poorly and was called low responder (LR).16-18 The opposite affinities are noted for human IgG; FcγRIIa-H/H131 is the only Fcγ receptor effectively interacting with IgG2, as shown with leukocytes.19 20

Currently, there is a debate about whether the allotype of FcγRIIa is correlated with the development of HIT and the clinical outcome of affected patients. Several studies addressing the distribution of the FcγRIIa-R-H131 polymorphism have been published recently.21-24 However, these studies have been performed with relatively low numbers of patients and their results have been discrepant. In this study, we prospectively determined the FcγRIIa-R-H131 polymorphism of 389 HIT patients and compared their genotype distribution with that of patients with thrombocytopenia or thrombosis who did not have HIT antibodies and with healthy blood donors. Additionally, we performed a subanalysis to assess the occurrence of the FcγRIIa-R-H131 polymorphism in HIT patients with isolated thrombocytopenia and in HIT patients presenting with TECs during heparin administration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and controls.

Patients (n = 389) with clinical symptoms of HIT and heparin-dependent antibodies as determined by the heparin-induced platelet activation (HIPA) test25 26 were investigated. In the HIPA test, heparin-dependent antibodies activate platelets via the FcγRIIa; thus, only patients with FcγRIIa-reactive HIT antibodies were included in the study. Patients without detectable HIT antibodies whom had either thrombocytopenia due to causes other than HIT (eg, leukemia, autoimmune thrombocytopenia, or sepsis) or a thrombotic event that was unrelated to heparin treatment (n = 351) and unrelated healthy blood donors (n = 256) served as control groups. All patients and controls were of Caucasian ethnicity. The patient groups originate from the whole of Germany, with 50% of the blood donors originating from the Northern part of Germany and 50% from the central part of Germany. Data for 122 of the 389 patients with acute HIT were obtained in a prospective treatment trial (unpublished data). Clinical data regarding these patients had been evaluated by an independent investigator and cross-checked with the patient file in an audit program. A subanalysis of these well-characterized patients was performed to determine the correlation between the FcγRIIa-R-H131 genotypes and the manifestation of TECs in HIT.

HIPA test.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared from citrated blood (1.6 vol adenine-citrate-dextrose [ACD] and 8.4 vol blood) from normal blood donors (with 10 medication-free days). PRP was acidified by the addition of 111 μL/mL ACD, and 5 U/mL apyrase (grade III; Sigma, Munich, Germany) were added. After centrifugation (7 minutes at 650g), the supernatant was discarded and platelets were carefully resuspended in 5 mL washing buffer (tyrode buffer containing 2.5 U/mL apyrase and 1.0 U/mL hirudin [Pentapharm, Basel, Switzerland], adjusted to pH 6.3 with HCl). The platelets were incubated in sealed tubes (15 minutes at 37°C), centrifuged (7 minutes at 650g), and resuspended in 1 mL suspension buffer (tyrode buffer containing 0.002 mol/L MgCl2 and 0.002 mol/L CaCl2, adjusted to pH 7.2 with HCl). The suspension was adjusted to 300,000 to 400,000 platelets/μL and incubated in a sealed tube (45 minutes at 37°C) before use. Heat-inactivated (56°C for 30 minutes) patient serum (20 μL) was dispensed in a microtiter plate (Greiner, Nürtingen, Germany). For intra-assay negative control, parallel samples are mixed with a high concentration of heparin (final concentration, 100 U/mL). This procedure disrupts heparin-PF4 complexes and detects antibodies that bind independently of the heparin concentration. Platelet suspension (75 μL) is added to all samples and, finally, the low concentration heparin (final concentration, 0.2 U/mL) is added to allow PF4/heparin complex formation. The microtiter plate was incubated (45 minutes at room temperature) on a magnetic stirrer (1,000 rpm) with two steel spheres (2 mm diameter; SKF, Schweinfurth, Germany). The transparency of the suspension was assessed using an indirect light source every 5 minutes. The patient sera was considered positive for HIT antibodies if the suspension became transparent due to platelet aggregation with 0.2 U/mL heparin but not with 100 U/mL heparin.

Primer design.

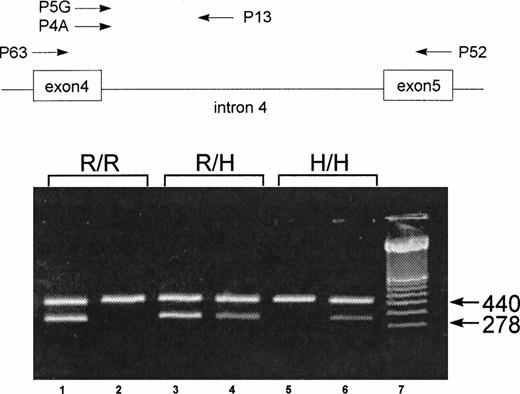

To genotype the FcγRIIa-R-H131 polymorphism, a new nested sequence-specific primer-polymerase chain reaction (SSP-PCR) method was developed. After the first PCR amplification, using primer pair P52 and P63,27 the product obtained was reamplified using sequence-specific primers. The sequence-specific sense primers P5G (specific for G507) and P4A (specific for A507) are located at the polymorphic site on exon 4, and a common antisense primer, P13, is located on intron 4 (Fig 1). Both exonic primers were constructed based on the published FcγRIIa cDNA sequence.28 To increase the specificity, two mismatch bases (T instead of C) were introduced at positions 502 and 504 in both primers. Because no data on the intronic sequences of FcγRIIa were available, we determined the nucleotide sequence of intron 4 by PCR using genomic DNA. After 30 amplification cycles with primers P63 and P52, a 1,000-bp product was isolated. Sequence analysis of this product identified an 800-bp intron with conserved donor and acceptor splice junctions. Based on this nucleotide sequence, we designed the antisense intronic primer, P13, located 118 bp downstream from exon 4, for the second-round PCR (Fig 1). A 440-bp fragment from the C-reactive protein (CRP) gene was used as an internal positive control.29 30All primers were purchased from Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium).

Schematic illustration of the localization of the primers for the nested SSP-PCR and representative results of FcγRIIa genotype of three individuals: homozygous FcγRIIa-R/R131 (R/R), heterozygous FcγRIIa-R/H131 (R/H), and homozygous FcγRIIa-H/H131 (H/H). For the FcγRIIa-specific amplification, primers P63 and P52 were used.27 For the allele-specific amplification, primers P5G (for the FcγRIIa-R131 allele) and P4A (for the FcγRIIa-H131 allele) were combined with a common antisense primer, P13. The 440-bp amplification product of CRP was used as an internal control. The 278-bp fragment represents the allele-specific amplification product from the SSP-PCR of FcγRIIa. Amplification with P13 and P5G (lane 1) and with P13 and P4A (lane 2) shows a homozygous FcγRIIa-R/R131 individual. Amplification with P13 and P5G (lane 3) and with P13 and P4A (lane 4) shows a heterozygous FcγRIIa-R/H131 individual. Amplification with P13 and P5G (lane 5) and with P13 and P4A (lane 6) shows a homozygous FcγRIIa-H/H131 individual. Lane 7 contains a molecular weight standard (100 bp).

Schematic illustration of the localization of the primers for the nested SSP-PCR and representative results of FcγRIIa genotype of three individuals: homozygous FcγRIIa-R/R131 (R/R), heterozygous FcγRIIa-R/H131 (R/H), and homozygous FcγRIIa-H/H131 (H/H). For the FcγRIIa-specific amplification, primers P63 and P52 were used.27 For the allele-specific amplification, primers P5G (for the FcγRIIa-R131 allele) and P4A (for the FcγRIIa-H131 allele) were combined with a common antisense primer, P13. The 440-bp amplification product of CRP was used as an internal control. The 278-bp fragment represents the allele-specific amplification product from the SSP-PCR of FcγRIIa. Amplification with P13 and P5G (lane 1) and with P13 and P4A (lane 2) shows a homozygous FcγRIIa-R/R131 individual. Amplification with P13 and P5G (lane 3) and with P13 and P4A (lane 4) shows a heterozygous FcγRIIa-R/H131 individual. Amplification with P13 and P5G (lane 5) and with P13 and P4A (lane 6) shows a homozygous FcγRIIa-H/H131 individual. Lane 7 contains a molecular weight standard (100 bp).

Nested SSP-PCR.

DNA was isolated from EDTA-anticoagulated peripheral blood using QIAAmp blood kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). One hundred nanograms of genomic DNA was added to 100 μL reaction mixes containing 10 mmol/L Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mmol/L KCl, 2.75 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.25 mmol/L of each dNTP, 100 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1 μmol/L each of P63 (5′-CAA GCC TCT GGT CAA GGT C) and P52 (5′-GAA GAG CTG CCC ATG CTG) primers, 20 nmol/L each of CRP I and CRP II primers, and 1 U of AmpliTaq (Perkin Elmer, Vaterstetten, Germany). PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95°C for 5 minutes, 55°C for 5 minutes, and 72°C for 5 minutes. This was followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 minute, 55°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 2 minutes, ending with an extension step at 72°C for 10 minutes. From this reaction, 1 μL was reamplified in the SSP-PCR using primers P13 (5′-CTA GCA GCT CAC CAC TCC TC) and P5G (5′-GAA AAT CCC AGA AAT TTTTCC G) or P4A (5′-GAA AAT CCC AGA AAT TTTTCC A). The allele-specific bases are in bold type and the inserted mismatch bases in the SSPs are underlined. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 minutes followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, with an extension step at 72°C for 10 minutes. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Nucleotide sequencing.

To analyze the polymorphic region, PCR products amplified by primers P63 and P52 were purified by Gene Clean (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and sequenced directly with primer P63 using Sequenase 2.0, as recommended by the manufacturer (Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany).

Method validation.

To assess intra-assay reproducibility, EDTA-anticoagulated blood was obtained from 80 patients at two different time points. In a blinded manner, these 160 samples were typed for FcγRIIa polymorphism. To validate the inter-assay reproducibility, leukocytes from genotyped donors were phenotyped for the FcγRIIa polymorphism using monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) in flow cytometric analysis (fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS]; n = 340) and3H-thymidine incorporation in a T-cell proliferation assay (n = 272).

Phenotypic analysis of FcγRIIa allotypes.

FACS scan analysis was performed according to standard methodology, using MoAb IV.3 (mIgG2b; Medarex, Annandale, NJ) that recognizes monomorphic epitopes on FcγRIIa and MoAb 41H16 (mIgG2a; kindly provided by Dr B.M. Longenecker, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) that reacts preferentially with FcγRIIa-R131.20 The anti-CD3–induced T-cell mitogenesis assays were performed as described by Tax et al,17including an extra reaction with human IgG2 anti-CD3 to allow discrimination between FcγRIIa-R/H131 and FcγRIIa-R/R131.20

Statistics.

Relative frequencies of the FcγRIIa genotypes were compared using χ2 statistics for contingency tables with 2 × 3 fields.31P values were calculated with the SPSS PC+ statistical package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Nested SSP-PCR.

Results of the SSP analyses for three representative individuals are shown in Fig 1. Amplification of genomic DNA from donor 1 resulted in a 278-bp specific product with primer P5G, but not with primer P4A. In contrast, with DNA from donor 3, this product could be amplified only with primer P4A. Both primers, P5G and P4A, amplified the 278-bp product from donor 2. In all reactions, the 440-bp internal control fragment of the CRP gene was present. These results indicate that donors 1, 2, and 3 represent homozygous FcγRIIa-R/R131, heterozygous FcγRIIa-R/H131, and homozygous FcγRIIa-H/H131, respectively.

Method validation.

Results of the nested SSP-PCR were validated by direct sequencing of the polymorphic region; no discrepancies were found (data not shown). Double sample processing (n = 80), FACS analysis using MoAbs recognizing FcγRIIa-R/H131 and FcγRIIa-R/R131 (n = 340), and anti-CD3–induced T-cell mitogenesis (n = 272) demonstrated the intra-assay and inter-assay reproducibility to be 100%.

Genotype distribution.

The genotype distributions and allele frequencies of the FcγRIIa-R-H131 polymorphism are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the genotype distribution between the two control groups (ie, non-HIT patients with thrombocytopenia or thrombosis and healthy blood donors; P = .45). However, in HIT patients, the FcγRIIa-R/R131 genotype was overrepresented and the FcγRIIa-H/H131 genotype was underrepresented when compared with non-HIT control patients (P < .001) and with healthy blood donors (P= .024). Approximately 50% of subjects in all three groups were FcγRIIa-R/H131 heterozygous.

Distribution of FcγRIIa Genotypes and Allele Frequencies in HIT Patients and Controls

| . | n . | FcγRIIa Allele Frequency . | FcγRIIa Genotype* . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R131 . | H131 . | R/R131 . | R/H131 . | H/H131 . | . | |||

| HIT patients | 389 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 105 (27.0) | 207 (53.2) | 77 (19.8) | P < .001-151 | |

| Non-HIT patients | 351 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 74 (21.1) | 166 (47.3) | 111 (31.6) | P = .45-151 | P = .024-151 |

| Healthy blood donors | 256 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 51 (19.9) | 134 (52.4) | 71 (27.7) | ||

| . | n . | FcγRIIa Allele Frequency . | FcγRIIa Genotype* . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R131 . | H131 . | R/R131 . | R/H131 . | H/H131 . | . | |||

| HIT patients | 389 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 105 (27.0) | 207 (53.2) | 77 (19.8) | P < .001-151 | |

| Non-HIT patients | 351 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 74 (21.1) | 166 (47.3) | 111 (31.6) | P = .45-151 | P = .024-151 |

| Healthy blood donors | 256 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 51 (19.9) | 134 (52.4) | 71 (27.7) | ||

*Values are the number of patients with the percentage in parentheses.

P values are calculated for FcγRIIa-R/R131, −R/H131, and −H/H131 genotype differences by χ2 test for contingency tables with 2 × 3 fields.

Correlation between FcγRIIa-R-H131 genotypes and manifestation of TECs.

In the subanalysis of 122 well-characterized patients, 68 patients (56%) developed TECs during heparin administration and 54 patients (44%) presented with isolated thrombocytopenia. In HIT patients who developed a TEC during heparin treatment, the FcγRIIa-R/R131 genotype was overrepresented and the FcγRIIa-R/H131 and FcγRIIa-H/H genotypes were underrepresented compared with HIT patients presenting with thrombocytopenia only; (P = .036; Table 2).

Distribution of FcγRIIa Genotypes and Allele Frequencies in a Subanalysis of 122 HIT Patients With Thrombocytopenia Only or With Thromboembolic Events During Heparin Administration

| . | n . | FcγRIIa Allele Frequency . | FcγRIIa Genotype* . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R131 . | H131 . | R/R131 . | R/H131 . | H/H131 . | |||

| HIT + TECs† | 68 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 25 (36.8) | 30 (44.1) | 13 (19.1) | P = .036‡ |

| HIT + thrombocytopenia† | 54 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 9 (16.7) | 28 (51.8) | 17 (31.5) | |

| . | n . | FcγRIIa Allele Frequency . | FcγRIIa Genotype* . | . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R131 . | H131 . | R/R131 . | R/H131 . | H/H131 . | |||

| HIT + TECs† | 68 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 25 (36.8) | 30 (44.1) | 13 (19.1) | P = .036‡ |

| HIT + thrombocytopenia† | 54 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 9 (16.7) | 28 (51.8) | 17 (31.5) | |

*Values are the number of patients with the percentage in parentheses.

HIT + TECs are HIT patients developing thromboembolic events during heparin administration. HIT + thrombocytopenia are HIT patients presenting with thrombocytopenia only.

P values are calculated for FcγRIIa-R/R131, −R/H131, and −H/H131 genotype differences by χ2 test for contingency tables with 2 × 3 fields.

DISCUSSION

HIT antibodies are known to interact with platelets via the FcγRIIa. The FcγRIIa carries a polymorphic site at position 131 (R-H) that affects its capacity to interact with immune complexes. In our investigation, the FcγRIIa-R/R131 genotype was overrepresented and FcγRIIa-H/H131 was underrepresented in HIT patients compared with non-HIT patients and healthy blood donors. Furthermore, a subanalysis with well-characterized HIT patients indicated a correlation between genotype and clinical manifestations of HIT. We found a significantly higher frequency of FcγRIIa-R/R131 in HIT patients who developed TECs than in patients presenting with isolated thrombocytopenia (P = .036; Table 2).

Four previous studies of the relationship between the FcγRIIa-R-H131 polymorphism and the development of HIT have been reported (Table 3).21-24 In three of these studies, FcγRIIa-H/H131 was found to be overrepresented in HIT patients.21,22,24 In the remaining study, no differences in the distribution of FcγRIIa-R-H131 genotypes were detected.23 It may be that the discrepancy between FcγRIIa genotype distribution in the present study and that of earlier studies is due to the inclusion of a different proportion of HIT patients with TECs. In three of the earlier studies, no data are given regarding the percentage of patients who developed HIT-related thrombocytopenia or HIT-related TECs.21,22,24 However, in the remaining study,23 23 of 36 patients had TECs and no significant differences in the FcγRIIa genotype distribution were found. The disparity in patient sample sizes between our study and earlier studies might also contribute to differences in results; ie, our study includes many HIT patients relative to the small number of HIT patients included in previous trials.

Summary of Previously Published Studies on the Impact of FcγRIIa-R-H131 Polymorphism in HIT Patients

| Study . | Patient Inclusion Criteria . | n . | FcγRIIa Genotype* . | Control Group . | n . | FcγRIIa Genotype* . | P . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R/R131 . | R/H131 . | H/H131 . | R/R131 . | R/H131 . | H/H131 . | ||||||

| Burgess et al21 | Clinical criteria of HIT† | 19 | 0 | 15 | 4 | Normal healthy individuals | 22 | 7 | 13 | 2 | <.05 |

| Brandt et al22 | Thrombocytopenia or thrombosis‡ | 96 | 22 (23) | 41 (43) | 33 (34) | Hospital controls | 100 | 32 (32) | 49 (49) | 19 (19) | <.05 |

| Arepally et al23 | Clinical criteria of HIT2-153 | 36 | 9 (25) | 19 (53) | 8 (22) | Outpatient controls | 102 | 26 (25) | 56 (55) | 20 (20) | .95 |

| Denomme et al24 | Clinical criteria of HIT2-155 | 84 | (23)¶ | (41)¶ | (36)¶ | Inpatient controls | 95 | (27)¶ | (52)¶ | (21)¶ | <.001 |

| Study . | Patient Inclusion Criteria . | n . | FcγRIIa Genotype* . | Control Group . | n . | FcγRIIa Genotype* . | P . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R/R131 . | R/H131 . | H/H131 . | R/R131 . | R/H131 . | H/H131 . | ||||||

| Burgess et al21 | Clinical criteria of HIT† | 19 | 0 | 15 | 4 | Normal healthy individuals | 22 | 7 | 13 | 2 | <.05 |

| Brandt et al22 | Thrombocytopenia or thrombosis‡ | 96 | 22 (23) | 41 (43) | 33 (34) | Hospital controls | 100 | 32 (32) | 49 (49) | 19 (19) | <.05 |

| Arepally et al23 | Clinical criteria of HIT2-153 | 36 | 9 (25) | 19 (53) | 8 (22) | Outpatient controls | 102 | 26 (25) | 56 (55) | 20 (20) | .95 |

| Denomme et al24 | Clinical criteria of HIT2-155 | 84 | (23)¶ | (41)¶ | (36)¶ | Inpatient controls | 95 | (27)¶ | (52)¶ | (21)¶ | <.001 |

*Values are the number of patients with the percentage in parentheses.

Thrombocytopenia occurring during heparin administration (resolving after heparin withdrawal), heparin-dependent antibodies detected in patient sera/plasma (platelet aggregometry or 14C-serotonin release assay), and exclusion of other recognized causes of thrombocytopenia.

Occurrence of thrombocytopenia or thrombosis during heparin administration and a positive platelet aggregation assay.

Published clinical criteria32a and diagnosis confirmed by detection of heparin-dependent antibodies (14C-serotonin release assay).

Thrombocytopenia occurring 5 or more days after start of heparin (resolving after discontinuation of heparin) and presence of HIT IgG (14C-serotonin release assay).

¶Only percentages are given in the publication.

It is possible that the differing distributions of FcγRIIa allotypes in HIT patients reflect normal variations in the FcγRIIa gene frequency, which are found not only among populations of different ethnic origins,27,32 but also within the Caucasian population, where the gene distribution ranges from 18% to 32% for FcγRIIa-R/R131 and from 19% to 36% for FcγRIIa-H/H131.22 33 However, this variability is not likely to affect our findings, because all of our patients and controls originate from the same population.

Our results lead us to speculate that, in HIT patients with the FcγRIIa-H/H131 allotype, uptake of antibody-coated platelets and PF4/heparin antibody complexes is enhanced. Thus, these patients are more likely to present with thrombocytopenia; whereas, in patients with the FcγRIIa-R/R131 allotype, the immune complexes are less efficiently removed from the circulation and might, therefore, cause prolonged immune-complex–dependent activation of platelets and endothelial cells, leading to TECs. Indeed, there is increasing evidence that the FcγRIIa-R131 allele is a risk factor for the manifestation of immune-complex–mediated diseases.34 The impaired phagocytosis of immune complexes seen in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be correlated to the presence of the R131 allele.35 SLE patients with the FcγRIIa-R/R131 allotype who remove the circulating immune complexes less efficiently develop lupus nephritis at a higher rate than do patients with the FcγRIIa-H/H131 allotype.36,37 Furthermore, the FcγRIIa polymorphism has an impact on the susceptibility to bacterial infections. Phagocytosis of IgG2-opsonized bacteria is less effective in individuals with the FcγRIIa-R/R131 allotype,38 and these patients exhibit a higher susceptibility to infections by encapsulated bacteria than patients with the FcγRIIa-H/H131 allotype.39,40 Accordingly, a low incidence of infections with encapsulated bacteria has been noted in the Japanese population,41 where the FcγRIIa-H/H131 allotype predominates.27 32 It is interesting to note that reports of HIT in Japanese patients are also very rare.

Because individuals with FcγRIIa-H/H131 effectively clear immune complexes, this allotype might be regarded as a protective factor against HIT-related thrombosis. Although there is evidence that platelets expressing the FcγRIIa-R/R131 phenotype interact more strongly with HIT antibodies in vitro than platelets with the FcγRIIa-H/H131 phenotype do,22 this need not contradict our hypothesis. Functional in vitro assays with isolated platelets cannot show interactions among cells of the reticulo-endothelial system, cells from the immune system, and platelets and cannot demonstrate the capacity to remove platelets and immune complexes from the circulation.

In two of the previous studies, the IgG subclass of the HIT antibodies was assessed.23,24 Both studies reported that the majority of HIT antibodies belonged to the IgG1 subclass. The FcγRIIa polymorphism is primarily responsible for binding differences in antibodies of the IgG2 and IgG3subclasses20; however, this polymorphism also seems to influence the interaction with immune complexes of the IgG1subclass.24

Like the present study, all four of the earlier studies used functional assays to determine the presence or absence of HIT antibodies. We chose this diagnostic technique because functional tests are based on the activation of platelets via the FcγRIIa receptor, and because we were studying FcγRIIa polymorphism, only patients with antibodies that reacted with FcγRIIa were of interest. Because the HIPA test is a functional assay that has been shown to have similar sensitivity and specificity as compared with the 14C-serotonin release assay,26 we do not see a major discrepancy to the laboratory methods reported in previous studies on FcγRIIa-R-H131 polymorphism in HIT patients. However, it is possible that HIT patients not identified in this study might have been identified using a PF4/heparin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Together, our findings and those of other published studies suggest that, although the polymorphism may not be the major risk factor for clinical manifestation of HIT, once HIT develops, patients with the FcγRIIa-R/R131 genotype might be at a higher risk of developing new TECs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The technical assistance of C. Blumentritt and A. Raether is highly appreciated, and the pre-PCR work by Dr K. Olbrich is gratefully acknowledged. We thank S. Owens for editorial help with the language.

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Gr 1096/2-2.

Address reprint requests to Andreas Greinacher, MD, Department of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-University, Sauerbruchstr., D-17487 Greifswald, Germany; e-mail:greinach@rz.uni-greifswald.de.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal