FIBRINOGEN IN HEMOSTASIS

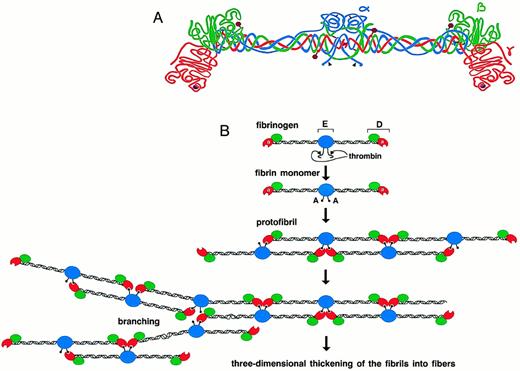

FIBRINOGEN IS A 340-kD glycoprotein that circulates in the blood at approximately 3 mg/mL, making it one of the most abundant blood proteins. It is composed of six polypeptide chains, (α, β, γ)2, which are held together by disulfide bonds and organized in a symmetrical dimeric fashion (Fig 1A).1-6 Limited plasmin proteolysis of fibrinogen generates fragments E and D.7Fragment E represents the central domain of the molecule and contains the amino termini of all six chains. The chains extend in coiled coils toward the distal globular regions (fragments D), which contain the carboxyl-terminal regions of the β and γ chains. The carboxyl-terminal region of the α chain has been shown to be noncovalently associated with the E domain.8 9

Schematic representation of human fibrinogen. The α chain is shown in blue, the β chain in green, and the γ chain in red. The black arrowheads indicate thrombin cleavage sites on the α chain. Glycosylation sites are shown as purple hexagons, while the calcium ions within the γ chains are represented as purple spheres (A). Schematic diagram showing the initial process of fibrin polymerization. The central nodules contain the amino-termini of all six chains(α,β,γ)2 and are referred to as the “E” regions, named after a fragment obtained by limited plasmin digestion of fibrin. They are flanked by two symmetric coiled coils that terminate in the distal “D” nodules. After the cleavage of fibrinopeptide A by thrombin, the newly exposed polymerization site “A” binds to the polymerization pocket “a” that is part of the γ chain of fibrin(ogen). The fibrin monomers thus align in a half-staggered, two-stranded arrangement to form long fibrils. Branch points and junctions occur sporadically (only one type is depicted here), contributing to the formation of a three-dimensional mesh (B).

Schematic representation of human fibrinogen. The α chain is shown in blue, the β chain in green, and the γ chain in red. The black arrowheads indicate thrombin cleavage sites on the α chain. Glycosylation sites are shown as purple hexagons, while the calcium ions within the γ chains are represented as purple spheres (A). Schematic diagram showing the initial process of fibrin polymerization. The central nodules contain the amino-termini of all six chains(α,β,γ)2 and are referred to as the “E” regions, named after a fragment obtained by limited plasmin digestion of fibrin. They are flanked by two symmetric coiled coils that terminate in the distal “D” nodules. After the cleavage of fibrinopeptide A by thrombin, the newly exposed polymerization site “A” binds to the polymerization pocket “a” that is part of the γ chain of fibrin(ogen). The fibrin monomers thus align in a half-staggered, two-stranded arrangement to form long fibrils. Branch points and junctions occur sporadically (only one type is depicted here), contributing to the formation of a three-dimensional mesh (B).

In the last stage of blood coagulation, thrombin cleaves the amino-termini of the α and β chains of fibrinogen, releasing fibrinopeptides A and B, respectively, and converting fibrinogen to fibrin monomers. The spontaneous polymerization of fibrin monomers initiates fibrin clotting with the formation of protofibrils. The newly exposed α-chain amino-terminus (GPR) of one fibrin molecule, which is referred to as the “A” polymerization site, binds noncovalently to a complementary polymerization pocket, termed the “a” site, in the carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain of a second fibrin(ogen) molecule. This “A-a” interaction aligns the fibrin monomers into half-staggered, two-stranded protofibrils (Fig 1B). Subsequently, the growing fibrils aggregate in a lateral fashion to form fibers, and this presumably involves interactions between the amino terminus of the β chain, the “B” polymerization site, and a complementary site, “b,” whose location is uncertain.10-14 Under physiological conditions, the release of fibrinopeptide B follows the release of fibrinopeptide A and correlates with lateral aggregation.15-17 This sequential release of fibrinopeptides, such that the “A” site appears before the “B” site, may control the final clot structure.18

After polymerization, the transglutaminase factor XIIIa19-21 forms covalent bonds between specific lysine and glutamine residues located within the carboxyl-terminal regions of adjacent γ chains22,23 and between α chains24-27 to form γ-γ dimers and α-polymers.28 These intermolecular bonds crosslink the fibrin gel network and, together with the factor XIIIa–mediated crosslinking of α2-antiplasmin to fibrin, solidify the clot, and render it more resistant to fibrinolysis.29-32

Fibrinolysis, or the lysis of the clot, is initiated by tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA)–mediated activation of plasminogen to plasmin. Both t-PA and plasminogen bind to fibrin,33 and the activation of plasminogen by t-PA is stimulated by its substrate, fibrin, which acts as an “effector” for plasmin formation.34,35 The rate of t-PA–catalyzed activation of plasminogen has been shown to depend on the formation of double-stranded protofibrils during fibrin polymerization.36,37 Plasmin then proteolyzes the fibrin mesh, thereby dissolving the clot. Hemostasis is achieved through maintenance of the delicate balance between the procoagulant, anticoagulant, and fibrinolytic reaction pathways. In whole blood, fibrin(ogen) also binds to the receptor GPIIbIIIa (αIIbβ3)38 on the surface of activated platelets and thereby mediates the formation of the platelet plug.

Bead model of the globular carboxyl-terminal region of the human fibrinogen γ chain, from Val143 to Val411. Mutations responsible for γ-dysfibrinogenemias are presented in red. Colored beads indicate stretches of α helix or β strand structure.

Bead model of the globular carboxyl-terminal region of the human fibrinogen γ chain, from Val143 to Val411. Mutations responsible for γ-dysfibrinogenemias are presented in red. Colored beads indicate stretches of α helix or β strand structure.

γ-CHAIN–RELATED FUNCTIONS

Many of the important intermolecular interactions of fibrin(ogen) are localized partly or entirely within the globular carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain. The primary polymerization pocket “a,” the γ-chain calcium-binding site, and the γ-γ factor XIIIa crosslinking site all reside in this region.22,23,49-56 The platelet-surface integrin GPIIbIIIa57-60 and the leukocyte integrin MAC-1 (αMβ2, CD11b/CD18)61-63 have been shown to interact with specific sites within this region of the fibrin(ogen) molecule. The γ chain of fibrin has also been implicated in plasminogen binding64and in t-PA binding and stimulation.65-68

FIBRINOGEN AND DISEASE

An elevated plasma fibrinogen level is associated with coronary atherosclerosis and is recognized as a significant independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.69-73 In fact, the predictive value of high fibrinogen levels for ischemic heart disease,69 myocardial infarction, and stroke74appears to be as important as high cholesterol levels. In vitro, high levels of fibrinogen have been shown, among other things, to correlate with lower fibrin gel porosity,75 to affect the rheological properties of blood,76 and to influence the thickness of the fibrin fibers.77

Dysfibrinogenemia refers to the presence in plasma of functionally abnormal fibrinogen due to a structural defect in the molecule. Inherited dysfibrinogenemia is recognized as a cause of hemorrhagic diathesis and bruising and is now also emerging as a significant risk factor for familial thrombophilia, heart disease, and stroke.78-86 The assessment of the risks that dysfibrinogenemias represent is complicated by the fact that most of the affected individuals are heterozygous for the mutation, with a circulating mixture of normal and abnormalfibrinogen. The molecular basis for the defect and the resulting symptoms vary greatly and those symptoms, when recognized, are usually episodic in nature. Further, to correlate the fibrinogen abnormality with the disease requires the thorough examination of several family members, often over long periods of time. Finally, the correlation with disease depends inherently on the diagnostic tests and their proper interpretation.

The analysis of dysfibrinogens at the molecular level has been challenging because of the size and complexity of the fibrinogen molecule. Over the last 15 years, the molecular defects of numerous inherited dysfibrinogenemias have been elucidated. These can be separated into two groups: those that affect the release of the fibrinopeptides A and B, and those that do not. The first group includes dysfibrinogenemias that are generally caused by the substitutions of amino acids situated at the amino-terminal regions of the α and β chains, specifically at or near the thrombin-cleavage sites, and tend to associate with bleeding complications.87These mutations interfere with the initial conversion of soluble fibrinogen to fibrin monomer, and they account for the majority of abnormal fibrinogens identified to date.88

The second group of dysfibrinogenemias is heterogeneous. It comprises mutations within the globular carboxyl-terminal regions of the three chains as well as mutations at the “A” and “B” polymerization sites that affect the “A-a” or “B-b” interactions. The clinical manifestations associated with this class of mutations vary from severe bleeding, to asymptomatic, to severe thrombophilia. Generally speaking, the mechanisms by which mutations in these regions of fibrin may cause these clinical manifestations have not been characterized as thoroughly as those belonging to the first group.

FIBRIN(OGEN) MOLECULAR STRUCTURE

Much valuable information on the dimensions and arrangement of domains within the molecule has been gained through electron microscopic and low-resolution crystallographic studies.89-94 These have provided a wealth of structural information detailing the overall size of the molecule, the arrangement of the six chains into a symmetric trinodular structure, and the structures of intermediates formed during polymerization and fibrinolysis. The final fibrin mesh can be visualized by electron microscopy, providing an important tool for analyzing abnormal fibrinogens. Seemingly minor structural abnormalities in fibrinogen can lead to drastic changes in the clot structure, causing alterations in fiber thickness, length, branching, and porosity.95 96

Although the high-resolution crystal structure of the entire 340-kD fibrinogen molecule remains an elusive goal, several high-resolution crystallographic structures of fibrinogen fragments have been published recently: the 2.1-Å structure of a recombinant 30-kD protein corresponding to the carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain,55 the same 30-kD protein complexed with the peptide GPRP,56 the 2.9-Å structure of the 86-kD proteolytic fragment D, and the 172-kD factor XIIIa–crosslinked D-dimer complexed with the peptide GPRP.97 The peptide GPRP mimics the amino terminus of the thrombin-cleaved fibrin α chain (the “A” polymerization site). The protein-peptide complex structures showed the exact position of the polymerization pocket “a” within the γ chain and identified the amino acids that interact with the fibrin α chain GPR residues.56 97

A recombinant protein (rFbgγC30) encoding the 30-kD carboxyl-terminal fragment of the γ chain of human fibrinogen (Val143-Val411) was expressed in a soluble secreted form98 in the yeastPichia pastoris, purified, and crystallized.55 A similar fragment of the γ chain, (the γ-module Ile148-Val411) was also expressed in Escherichia coli as an insoluble protein and refolded in vitro.63 Both of the recombinant proteins were shown to be functional with respect to calcium binding, crosslinking by factor XIIIa, and platelet binding.63 98 These studies represent a “modular” approach to fibrinogen research where small regions within this complex molecule can be expressed and characterized without the complicating factors such as partial degradation and heterogeneity that are associated with fibrinogen isolated from plasma.

The three-dimensional x-ray structures of human fibrinogen fragment D and of the factor XIIIa–crosslinked D dimer complexed with the peptide GPRP amide were determined to 2.9-Å resolution.97 This 86-kD fragment D comprises the carboxyl-terminal regions of the β and γ chains, as well as a short section of the α chain (α111-197, β134-461, γ88-406). In fragment D, the carboxyl-terminal regions of the β and γ chains are globular, with the γ chain comprising the distal end of the outer nodule.97 The overall fold of the β and γ carboxyl terminal regions is similar, as was expected from their strong sequence similarity.99

The fragment D dimer was seen to have an extensive γ:γ end-to-end “self-association” interface that is formed as the distal nodules of fibrin become aligned during polymerization, before crosslinking by factor XIIIa. The characteristics of this γ:γ interface are of great interest, as it has been hypothesized that some fibrinogen mutations delay polymerization by interfering with the alignment of the distal nodules at this interface.100,101 The final 8 to 20 residues at the carboxyl-terminal end of the γ chains were not visible in the electron density for the γ-chain fragment and fragment D crystal structures. Several studies have indicated that this region can adopt multiple conformations.55 102-106

The recent crystallographic studies have led to new insights into the structure-function relationships of the complex molecule that is fibrin(ogen). In particular, we can now correlate the clinical manifestations and the biochemical information available for the dysfibrinogens with what is now known about the three-dimensional structure of the molecule.

γ-DYSFIBRINOGEMIAS

Dysfibrinogenemias and their pathologies have been reviewed previously.78,84,87,107-110 The goal of this review is to examine the dysfibrinogemias, 37 to date, with identified molecular defects situated within the carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain (Fig 2). Table 1 summarizes the available biochemical and clinical information. For all of the γ-dysfibrinogens, the thrombin time was prolonged, fibrin polymerization was impaired, and the release of fibrinopeptides A and B was normal. The mutations were identified either by proteolytic peptide sequencing or by sequencing of PCR-amplified genomic DNA. The structural information presented below is derived from the rFbgγC30 structures,55 56 unless specified otherwise.

Summary of γ-Dysfibrinogens

| Mutation . | Name . | Sex/ Age . | Ca2+ Binding . | γ-γ FXIIIaCrosslinking . | Hetero/ homozygous . | Clinical Symptoms (no. of episodes) . | Relative(s) . | References . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrin . | fbg . | ||||||||

| G268E | Kurashiki I | M/58 | N | A | HM | ASYMPT | 101 | ||

| R275C | Baltimore IV | M/56 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 116, 117 | |||

| Bologna I | F/20 | THROMB | 2 | 84 | |||||

| Cedar Rapids I | HT | THROMB(2)-150 | 2-151 | 122 | |||||

| Milano V | F/51 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 119,199 | ||||

| Morioka I | N | HT | ASYMPT | 115 | |||||

| Osaka II | M/48 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 113 | ||||

| Tochigi I | M/51 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 88, 114 | ||||

| Tokyo II | F/39 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 100, 118 | ||||

| Villajoyosa I | F/27 | HT | ASYMPT | 120 | |||||

| R275H | Barcelona III | M/71 | HT | THROMB(1) | 0 | 120 | |||

| Barcelona IV | M/28 | HT | ASYMPT | 120 | |||||

| Bergamo II | F | HT | THROMB(M) | 5 | 126 | ||||

| Claro I | F/42 | N | HT | ASYMPT-152 | 128, 199 | ||||

| Essen I | M | HT | ASYMPT | 126 | |||||

| Haifa I | F/30 | N | N | HT | THROMB(≥2) | 1 | 95, 130, 131 | ||

| Osaka III | F/38 | N | N | HT | ASYMPT | 127 | |||

| Perugia I | M/2 | HT | ASYMPT | 126 | |||||

| Saga I | F/16 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 129 | ||||

| G292V | Baltimore I | F/29 | N | HT | THROMB(M)-153 | 133-137 | |||

| N308I | Baltimore III | F/30 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 140, 141 | |||

| N308K | Bicêtre II | M/40 | THROMB(≥2) | 0 | 144 | ||||

| Kyoto I | M/45 | N | N | HT | ASYMPT | 142, 143 | |||

| Matsumoto II | F/49 | HT | BLEED-155 | 1 | 145 | ||||

| M310T | Asahi I | M/33 | A | A | HT | BLEED(M) | 146, 147 | ||

| D318G | Giessen IV | F/18 | THROMB-150,-153¶ | 0 | 84 | ||||

| ΔN319,D320 | Vlissingen I | F/23 | A | HT | THROMB | ≥6 | 152 | ||

| Q329R | Nagoya I | F/43 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 153-155 | |||

| D330V | Milano I | N | N | HT | ASYMPT | 156, 199 | |||

| D330Y | Kyoto III | F/50 | HT | ASYMPT | 157 | ||||

| N337K | Bern I | F/24 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 158, 159, 199 | |||

| ∇γ350 | Paris I | A | A | 160-165 | |||||

| S358C | Milano VII | F/21 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 166, 199 | |||

| D364H | Matsumoto I | M/1 | HT | ASYMPT | 167 | ||||

| D364 V | Melun I | F/40 | HT | THROMB(M) | 8 | 168 | |||

| R375G | Osaka V | F/44 | A | HT | ASYMPT | 172 | |||

| K380N | Kaiserslautern I | N | HM | THROMB | 177 | ||||

| Mutation . | Name . | Sex/ Age . | Ca2+ Binding . | γ-γ FXIIIaCrosslinking . | Hetero/ homozygous . | Clinical Symptoms (no. of episodes) . | Relative(s) . | References . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrin . | fbg . | ||||||||

| G268E | Kurashiki I | M/58 | N | A | HM | ASYMPT | 101 | ||

| R275C | Baltimore IV | M/56 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 116, 117 | |||

| Bologna I | F/20 | THROMB | 2 | 84 | |||||

| Cedar Rapids I | HT | THROMB(2)-150 | 2-151 | 122 | |||||

| Milano V | F/51 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 119,199 | ||||

| Morioka I | N | HT | ASYMPT | 115 | |||||

| Osaka II | M/48 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 113 | ||||

| Tochigi I | M/51 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 88, 114 | ||||

| Tokyo II | F/39 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 100, 118 | ||||

| Villajoyosa I | F/27 | HT | ASYMPT | 120 | |||||

| R275H | Barcelona III | M/71 | HT | THROMB(1) | 0 | 120 | |||

| Barcelona IV | M/28 | HT | ASYMPT | 120 | |||||

| Bergamo II | F | HT | THROMB(M) | 5 | 126 | ||||

| Claro I | F/42 | N | HT | ASYMPT-152 | 128, 199 | ||||

| Essen I | M | HT | ASYMPT | 126 | |||||

| Haifa I | F/30 | N | N | HT | THROMB(≥2) | 1 | 95, 130, 131 | ||

| Osaka III | F/38 | N | N | HT | ASYMPT | 127 | |||

| Perugia I | M/2 | HT | ASYMPT | 126 | |||||

| Saga I | F/16 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 129 | ||||

| G292V | Baltimore I | F/29 | N | HT | THROMB(M)-153 | 133-137 | |||

| N308I | Baltimore III | F/30 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 140, 141 | |||

| N308K | Bicêtre II | M/40 | THROMB(≥2) | 0 | 144 | ||||

| Kyoto I | M/45 | N | N | HT | ASYMPT | 142, 143 | |||

| Matsumoto II | F/49 | HT | BLEED-155 | 1 | 145 | ||||

| M310T | Asahi I | M/33 | A | A | HT | BLEED(M) | 146, 147 | ||

| D318G | Giessen IV | F/18 | THROMB-150,-153¶ | 0 | 84 | ||||

| ΔN319,D320 | Vlissingen I | F/23 | A | HT | THROMB | ≥6 | 152 | ||

| Q329R | Nagoya I | F/43 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 153-155 | |||

| D330V | Milano I | N | N | HT | ASYMPT | 156, 199 | |||

| D330Y | Kyoto III | F/50 | HT | ASYMPT | 157 | ||||

| N337K | Bern I | F/24 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 158, 159, 199 | |||

| ∇γ350 | Paris I | A | A | 160-165 | |||||

| S358C | Milano VII | F/21 | N | HT | ASYMPT | 166, 199 | |||

| D364H | Matsumoto I | M/1 | HT | ASYMPT | 167 | ||||

| D364 V | Melun I | F/40 | HT | THROMB(M) | 8 | 168 | |||

| R375G | Osaka V | F/44 | A | HT | ASYMPT | 172 | |||

| K380N | Kaiserslautern I | N | HM | THROMB | 177 | ||||

All propositi were found to have impaired fibrin polymerization and normal fibrinopeptide release. The number of episodes is shown in parentheses, if reported. Relatives refers to the number of relatives showing clinical symptoms similar to those of the propositus (but not necessarily the dysfibrinogenemia). Blanks indicate that data were unavailable or not found.

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; N, normal; A, abnormal; fbg, fibrinogen; HT, heterozygous; HM, homozygous; ASYMPT, asymptomatic; THROMB, thrombosis; BLEED, bleeding; M, multiple.

The propositus was also found to be heterozygous for the factor V Leiden defect.

All affected relatives were heterozygous for both the dysfibrinogenemia and the factor V Leiden defect.

Had two spontaneous abortions.

Also suffered from mild bleeding.

Easy bruising and postpartum bleeding.

¶Personal communication from Drs F. Haverkate and R.M. Bertina, December 1997.

G268E.

Fibrinogen Kurashiki I was identified in a 58-year-old man who was homozygous for this molecular defect and experienced no major bleeding or thrombosis.101 Crosslinking of the fibrin γ chains appeared to proceed normally. In contrast, the crosslinking of fibrinogen Kurashiki I by factor XIIIa was delayed, compared with normal fibrinogen. The rate of plasminogen activation by t-PA was not enhanced by fibrin Kurashiki I to the same extent as is typically seen with normal fibrin.101 The investigators concluded that the G268E substitution would disturb the D:D association, possibly by introducing repulsive forces at a γ:γ interaction site between two dysfibrinogen molecules. This would in turn lead to alterations in the protofibril alignment and to the observed delay in fibrin polymerization.101 This hypothesis was based in part on the close proximity of G268 to R275, which has been proposed to be an important participant in the D:D interaction.100

In the crystal structure of rFbgγC30, the backbone nitrogen of G268 is hydrogen bonded to the carbonyl oxygen of R275, and these two residues flank a surface-exposed chain reversal comprising residues 269 through 274, with a sharp β turn at A271 and D272. Mutations at R275 have also been identified in dysfibrinogens (see next section). G268 exhibits no backbone strain, so the effects of mutations at this site are not likely to alter the backbone conformation. Because G268 is exposed to the solvent, a glutamic acid side chain can be modeled in rFbgγC30, without encountering atomic overlaps with neighboring residues. The fact that bovine111 and lamprey112 fibrinogens both encode a threonine at position γ268 further supports the hypothesis that the observed defect in polymerization is likely caused by the introduction of a negative charge here, rather than by strain caused by the bulkiness of the glutamic acid residue.101

Because G268 is approximately 24 Å from the “a” site and 20 Å from the calcium atom, respectively, it is unlikely that the G268E substitution would affect either the polymerization pocket or the calcium site directly. The normal crosslinking of fibrin Kurashiki I would imply that the D:E interaction provides enough stabilization energy to overcome the proposed D:D repulsion caused by the mutated residue. Thus, the half-staggered arrangement of mutant protofibrils would presumably be close to the normal fibrin structure.

R275C, H.

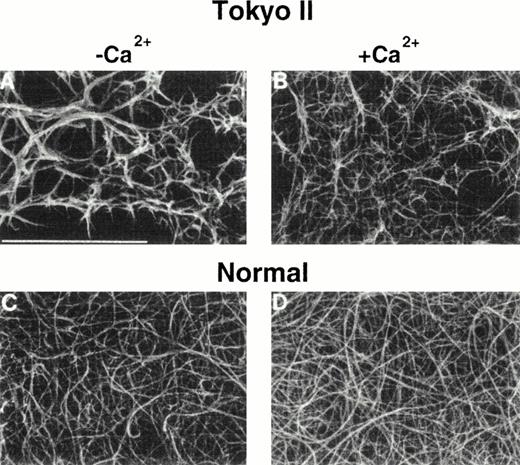

The amino acid γR275 is the site of mutation for at least 18 dysfibrinogenemias (Table 1), making it the most commonly mutated site within the carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain. Fibrinogens Osaka II,113 Tochigi I,114 Morioka I,115Baltimore IV,116,117 Tokyo II,100,118 Milano V,119 and Villajoyosa I120 were also characterized as R275C substitutions. In the case of fibrinogen Osaka II,113 the new cysteine residue was shown to be linked to a free cysteine. R275C-fragment D1 that was prepared from fibrinogen Osaka II failed to prolong significantly the fibrinogen clotting time,113 in contrast to normal fragment D1.121 The binding of t-PA and plasminogen to fibrin Villajoyosa I was found to be normal.120 The normal factor XIIIa–catalyzed crosslinking of fibrin Tokyo II was interpreted as indicating a normal D:E interaction.100 Electron microscopic images of crosslinked fibrinogen Tokyo II showed that it failed to form elongated, double-stranded fibrils. Furthermore, in contrast to normal fibrin, fibrin Tokyo II formed tapered terminating fibers with extensive branching of the clot network. The investigators concluded that the mutation R275C causes a functionally abnormal D:D association site100 that results in impaired fibrin assembly.

In contrast to the asymptomatic R275C propositi listed above, fibrinogen Bologna I was identified in a 20-year-old woman who suffered multiple episodes of venous thrombosis. Protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III deficiencies were ruled out as risk factors.84 Recently, fibrinogen Cedar Rapids (R275C) was identified in three second-generation family members with severe pregnancy-associated thrombophilia.122 These patients were also heterozygous for the Factor V Leiden defect.123-125Interestingly, first-generation family members who carried only the Factor V Leiden defect or only the dysfibrinogen had no history of thrombophilia. These findings suggested that thrombophilia is associated via the presence of both defects.122

The molecular substitution R275H is also commonly encountered. The R275H dysfibrinogens Essen I,126 Perugia I,126Osaka III,127 Barcelona IV,120 and Claro I128 were isolated from asymptomatic patients. Fibrinogen Bergamo II was isolated from a patient who, along with several members of her family, suffered from recurrent thromboembolism,126while Fibrinogen Saga I was found in a patient with hematuria.129 Fibrinogen Haifa I was described in a 30-year-old woman who experienced severe intermittent claudication after short walks, due to bilateral occlusion of the superficial femoral arteries.130 The Fibrinogen Barcelona III propositus suffered a single postsurgical thrombotic event at age 32,120 and the Claro I propositus had two spontaneous abortions.128 These findings are suggestive, but not conclusive, of a possible association between mutations at R275 and a tendency to thrombosis.

Calcium binding, platelet aggregation, and factor XIIIa–mediated crosslinking appeared to be normal in Fibrinogen Haifa.131However, the presence of calcium ions did not protect its fragment D against plasmin cleavage at position K302-F303,131 as would be expected for normal fragment D.132 An electron microscopic study of polymerized fibrin Haifa I showed an abnormal, highly branched matrix, with the fibers appearing generally thinner than those seen in normal polymerized fibrin.95 In contrast to fibrinogen Haifa I, fragment D1 derived from fibrinogen Saga I was fully protected by calcium ions against plasmin degradation, but it failed to inhibit fibrinogen clotting.129

In the rFbgγC30 structure, residue R275 is surface-exposed, flanking a chain reversal comprising residues 269-274. As mentioned previously, a β turn between residues 270 and 271 brings the backbone of R275 in close proximity to G268, allowing a hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen of R275 and the nitrogen of G268. A salt link between R275 and D272 further stabilizes this chain reversal. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that amino acid substitutions that alter this β turn may cause similar disruptions in the protein structure. This could in turn affect the interactions of this region with other proteins. The participation of R275 in a D:D interface was confirmed by the three-dimensional structure of the factor XIII-crosslinked D dimer.97

The side chain of R275 is involved in another very important interaction, because it forms two hydrogen bonds with the backbone of G309, thus clearly providing extra stabilization for this region of the protein. The backbone nitrogen atom of G309 is hydrogen bonded to the backbone carbonyl atom of L276 as well as to the side chain oxygen of N308. The N308 side chain in turn shares two hydrogen bonds with the backbone of Y278. The importance of the proper alignment of residues in this region is highlighted further by the localization here of several other molecular defects associated with dysfibrinogenemias; ie, N308I, N308K, and M310T (see below).

G292V.

Dysfibrinogen Baltimore I was diagnosed more than 30 years ago in a 29-year-old woman suffering from femoral vein thrombosis after minor trauma.133-135 The patient had a history of mild hemorrhagic diathesis characterized by frequent bruising, epitaxis, and hemorrhage as well as previous severe recurrent thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Fibrinogen Baltimore I showed delayed fibrin polymerization that could be partially corrected by addition of calcium.133 The defective formation of factor XIIIa–crosslinked α-polymers was corrected by increased calcium concentration or lowered pH conditions.136 Plasmin degradation of fibrinogen Baltimore I was normal and its fragment D was protected effectively by calcium. The amino acid substitution G292V was identified as the molecular defect.137

G292 lies in the middle of a highly conserved stretch of amino acids,99 approximately 10 Å from the polymerization pocket and 18 Å from the calcium atom.55 Upon first inspection of the crystal structures,55,56 G292 appears to be isolated from the clusters of residues linked to other dysfibrinogenemias. G292 is located at the surface of the protein, and the backbone dihedral angles of (φ,ψ) = (101o,164o) indicate that substitution of a nonglycine residue at this site would lead to backbone strain and destabilize the structure. Further, the side chain of N337, which points away from the polymerization pocket, is only 7 Å from G292. It is plausible that insertion of a bulky valine side chain at position 292 would alter the region surrounding N337. N337 is part of an unusual, highly strained region of the the γ chain. Its dihedral angles indicate backbone strain, and it lies immediately adjacent to a cis peptide bond between residues K338 and C339. This strained conformation enables the backbone of C339 to form an additional hydrogen bond with the fibrin α chain amino-terminal residues GPR.56 This strained conformation is stabilized in part by an extensive network of hydrogen bonds, including the hydrogen bonds between the N337 side chain and its neighbors. Therefore, any disruption of the environment of the N337 side chain could destabilize its backbone, altering the polymerization pocket and thereby fibrin polymerization.

Residues F303 and F304 are positioned in between G292 and N337. Both the phenyl rings are directed to the surface of the molecule. It has been well established from solvent transfer studies138 139that the phenylalanine side chain is reasonably soluble in both polar and nonpolar solvents; hence, its occurrence both in the hydrophobic cores of proteins and at their solvent-exposed surfaces. The valine side chain, by contrast, occurs almost exclusively in hydrophobic environments, and is typically buried in solvent-inaccessible protein cores. The substitution of a valine for G292 would promote hydrophobic interactions between the valine and phenylalanine side chains, thus altering the molecular surface significantly. Further, the surface exposure of the hydrophobic valine side chain would decrease the entropy, and thus the stability of the protein. Therefore, we propose that the substitution G292V leads to the structural destabilization of a fairly large region of the protein, and that this affects the polymerization pocket directly.

N308I, K.

The dysfibrinogenemia Baltimore III was diagnosed in an asymptomatic 30-year-old woman who had a prolonged thrombin time that was corrected by excess calcium.140 The defect was identified as an N308I mutation.141 The fibrinogen showed normal crosslinking by FXIIIa, normal calcium binding, and delayed fibrin monomer polymerization.140 141

The N308K mutation was identified in fibrinogens Kyoto I,142,143 Bicêtre II,144 and Matsumoto II.145 The clinical manifestations associated with the N308K substitution varied greatly. Fibrinogen Kyoto I was isolated from an asymptomatic, hypofibrinogenic male who had a family history of both thrombotic and bleeding problems142,143. Fibrinogen Bicêtre II was isolated from a man who suffered a spontaneous deep-vein thrombophlebitis and a pulmonary embolism.144Finally, fibrinogen Matsumoto II was isolated from a woman with Graves' disease who had a tendency to bruise easily and who had experienced moderate to severe bleeding after each of her three deliveries.145 For fibrinogen Bicêtre II, it was shown that the mutation did not affect binding to t-PA or to plasminogen, thus eliminating these possible explanations for the thrombotic incidents.144

The residue N308 is situated on the surface of rFbgγC30. For that reason, the introduction of a hydrophobic amino acid such as isoleucine at this position would appear to be very destabilizing. In structure-based sequence alignments, N308 is conserved in all of the α-extended, β-, and γ-chain sequences except in the lamprey fibrinogen γ chain, where it is replaced by a leucine.55,97 99 Although a lysine residue should be accommodated easily on the surface of rFbgγC30, a positive charge here could disrupt interactions with other fibrinogen domains. The new lysine residue could also change the pattern of cleavage by plasmin, thereby affecting fibrinolysis. This possibility has not been addressed experimentally.

The side chain of N308 forms hydrogen bonds with the backbone nitrogen and carbonyl oxygen of Y278.56 An additional hydrogen bond connects the side-chain oxygen of N308 with the backbone nitrogen of G309, as discussed in the context of the mutations at G268 and R275. A cluster of residues including N308, G309, G268, R275, and M310 is exposed to the solvent in both the rFbgγC30 and fragment D structures, and is in the vicinity of the D:D interface of the factor XIIIa-crosslinked D dimer structure.97 This interaction site is presumably buried during the initial contact between the D domains, in the early stages of fibrin polymerization. Thus, the introduction of bulky or charged side chains at N308 would be expected to disrupt the initial alignment of fibrin monomers into protofibrils. We would expect the clot structure in these patients to be altered in a manner similar to that seen with fibrinogen Tokyo II.100

M310T.

Dysfibrinogenemia Asahi I was diagnosed in a 33-year-old man sufferering from posttraumatic bleeding after a traffic accident. He had experienced moderate hemorrhage related to injuries and delayed wound healing since adolescence.146 The mutation M310T creates a consensus sequence, N308-G309-T310, that directs N-linked glycosylation, and, indeed, the attachment of a carbohydrate moiety to N308 was confirmed.146 The factor XIIIa–mediated γ-γ crosslinking of fibrinogen and of fibrin Asahi I were both markedly delayed, even though the γ chain amine acceptor Q398 functioned normally when assayed by monodansylcadaverine incorporation. The delayed fibrin(ogen) crosslinking rate indicated therefore that the abnormal molecules were unable to align properly.146 147

The extent of fibrinogen glycosylation affects fibrin polymerization and lateral aggregation, as well as the structural and mechanical properties of the clot.148 For example, desialylated fibrin polymerizes faster than normal fibrin149 and clots containing deglycosylated fibrin(ogen) form faster and display thicker, underbranched fibers, resulting in a more porous mesh.150Conversely, clots formed from hyperglycosylated fibrinogen (as would be the case for fibrinogen Asahi I) assemble more slowly.151

Alignment of the human γ-chain sequence with a series of homologous sequences55,97 99 shows that the methionine at position 310 is strictly conserved among the fibrinogen sequences. Nevertheless, the substitution M310T would appear to be structurally benign. Because the residue is surface-exposed and is not involved in any hydrogen bonds, it is difficult to argue compellingly for the unique contribution of M310 to the structural integrity of this region. Therefore, we propose that the primary consequence of mutations at this site is in the disruption of D:D interactions by the new glycosylation, and that the effects of this mutation are analogous to those resulting from substitutions at the γ chain positions R275, G268, G292, and N308.

D318G.

Fibrinogen Giessen IV (sometimes referred to as Kassel), was identified in an 18-year-old woman who suffered from recurrent venous thrombosis as well as mild bleeding.84 She was later found to be heterozygous for the factor V Leiden defect (personal communication from Drs F. Haverkate and R.M. Bertina, Leiden, The Netherlands, December 1997). The only relative of the patient who was found to have this dysfibrinogenemia did not experience thrombosis; it is not known whether this individual was also heterozygous for the Factor V Leiden defect. The side chain of aspartate 318 is directly involved in binding to the calcium ion in the γ chain.55The removal of this carboxyl group would obviously have a detrimental effect on calcium binding, presumably impairing the regulation of fibrin polymerization and the protection of the γ chain by calcium ions.

ΔΝ319,D320.

Fibrinogen Vlissingen I was identified in a 23-year-old woman who was hospitalized with a massive pulmonary embolism.152 The father and daughter of the patient also showed prolonged fibrinogen clotting times, although they were asymptomatic. The same 2–amino acid deletion was found in fibrinogen Frankfurt IV, in a patient with thrombosis. A subsequent family history showed that these two patients were related.84 Fibrin polymerization was delayed both in the presence and absence of calcium. Calcium was only partially effective in protecting this fibrinogen against plasmin degradation. Calcium binding was measured by equilibrium dialysis, and showed the loss of one high-affinity Ca2+-binding site within fibrinogen Vlissingen I fragment D.152 DNA sequence analysis showed that the patient was heterozygous for a deletion of the six nucleotides encoding N319 and D320. It was concluded that these residues were essential for γ calcium ion binding. Clotting of the mutant fibrinogen in the presence of EDTA was also delayed relative to normal fibrinogen, suggesting that the deletion affected not only the calcium-binding site, but also the polymerization site “a” within the γ chain. In rFbgγC30, the polymerization site appears to function relatively independently from the calcium-binding site. This is illustrated by the fact that the fragment can bind GPRP even after treatment with EDTA.98 Nevertheless, the Vlissingen I data suggest that a disruption of the structure at one site could well affect the folding of the other, leading to a polymerization defect.

Q329R.

Fibrinogen Nagoya I was found in three generations of a clinically asymptomatic Japanese family.153 Fibrin monomer polymerization was defective, while factor XIIIa–catalyzed crosslinking of fibrin was normal. The γ chain of fibrinogen Nagoya I showed abnormal behavior on CM-cellulose chromatography and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).154 A single amino acid substitution of glutamine by arginine at position 329 was shown by peptide amino acid sequence analysis.155

A comparison of the 30-kD γ-chain structures, both uncomplexed55 and complexed with the fibrin α chain-mimicking peptide GPRP,56 shows that upon binding of GPRP, Q329 shifts its position to accommodate arginine 3 of the peptide and forms a hydrogen bond with it.56 The recombinant γ chain fragment with the substitution Q329R (rFbgγC30-Q329R) was not protected against plasmin degradation in the presence of the peptide GPRP and EDTA, presumably because the mutation abolished GPRP binding.98 This suggests that the mutant arginine side chain blocks access to the “a” site of fibrin(ogen), quite possibly by occupying the preexisting arginine-binding site within the polymerization pocket.

D330V, Y.

Fibrinogen Milano I (D330V) was identified in a young girl and her father, both of whom were clinically asymptomatic.156 A second dysfibrinogenemia involving this amino acid, fibrinogen Kyoto III (D330Y), has been described in an asymptomatic 50-year-old woman.157 Her two sons showed the same abnormality, and fragment D1 isolated from the second son was not effective in inhibiting fibrinogen clotting. Because aspartic acid and tyrosine have very different pKa's, it was hypothesized that the point mutation perturbed the local folding of the γ chain, thus altering the structure required for fibrin polymerization.157

The crystal structure of the rFbgγC30-GPRP complex56showed that D330 forms a salt link with the arginine side chain of the peptide, providing an interaction essential for D:E binding. Furthermore, the carboxyl group of D330 is hydrogen-bonded to the side chain of H340. The backbone carbonyl oxygen of H340 forms an additional hydrogen bond with the peptide amino terminus, and the backbone nitrogen is hydrogen-bonded to the peptide glycine carbonyl oxygen. Therefore, the replacement of D330 by an uncharged amino acid residue such as tyrosine or valine would significantly alter the electrostatic environment of the polymerization pocket. The addition of these bulky side chains would necessarily alter the extensive and precise network of hydrogen bonds within the polymerization pocket. These disruptions are consistent with the markedly prolonged clotting times of patients carrying this mutation.

N337K.

Fibrinogen Bern I was discovered in a 24-year-old asymptomatic woman.158 Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis showed an abnormal mobility for the γ chain of fragment D derived from fibrinogen Bern I.159 N337 lies in a region of the γ chain that is highly conserved among mammals. It is part of a very constrained chain reversal within the γ chain,56 as described earlier in the G292V section. The side chain of N337 participates in three hydrogen bonds to S306 and F303 and points away from the polymerization pocket, toward the solvent. Although a lysine residue could be accommodated in this position, several N337 hydrogen bonds that stabilize the strained backbone conformation at the polymerization pocket would be lost.

Paris I (insertion at γ350).

Fibrinogen Paris I is characterized by impaired fibrin polymerization and clot retraction.160 Fibrin Paris I monomers inhibited the polymerization of normal fibrin monomers, did not form γ-γ dimers, and did not incorporate dansylcadaverine in the presence of factor XIIIa.161,162 Approximately 2/3 of the Paris I fibrinogen γ chain exhibited an apparent molecular weight higher (≈2.5 kD) than normal.161 Electron microscopic studies on fibrin Paris I showed abnormal clumps connected by thin irregular fibers, with frequent terminations.163 Fibrinogen Paris I also failed to support adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-induced platelet aggregation.164 The molecular defect was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis to be an A → G point mutation within intron 8 of the γ chain gene. It is hypothesized that alternative splicing, due to this nucleotide change in the Paris I mRNA, leads to the insertion of 15 amino acids after Q350, including two cysteine residues, and to the substitution of G351 for a serine.165 No association with bleeding or thrombosis has been reported for this dysfibrinogenemia.

The insertion of 15 amino acids at residue Q350 cannot be modeled with reliability. Nevertheless, we can speculate that this large insertion within the polymerization domain would cause a major structural reorganization, quite possibly precluding the formation of functional polymerization and crosslinking sites.

S358C.

Fibrinogen Milano VII was identified in an asymptomatic 21-year-old woman.166 No family member had a hemorrhagic or thrombotic tendency, but several had a prolonged thrombin time. The fibrin Milano VII clots had an abnormal “transparent” appearance when compared with clots obtained from normal fibrinogen.166 The S358C mutation creates an unpaired cysteine residue, and immunoblotting analysis determined that the abnormal fibrinogen circulated as a disulfide-linked complex with the abundant blood protein albumin. Interestingly, removal of albumin failed to normalize the fibrin polymerization profile. This suggested that the defect was not due to steric hindrance created by albumin, but rather was attributable directly to the substitution.166

The three-dimensional structure of rFbgγC30 shows that S358 is indeed on the protein surface, making the new cysteine residue available to react with other free cysteines.55 56 S358 does not interact directly with either the polymerization pocket or the calcium site, and it does not appear to be part of the D:D interaction site. It is possible that the substitution leads to a general structural destabilization of the polymerization domain, but there is no direct evidence for this. The observed transparency of fibrin Milano VII clot suggests to us a possible effect on the lateral aggregation of fibrils.

D364H,V.

Dysfibrinogenemia Matsumoto I was identified recently in a 1-year-old boy who had Down Syndrome and congenital heart disease. The young patient showed no signs of bleeding or thrombotic tendencies, nor did his two relatives who also showed prolonged thrombin times. The D364H mutation was identified in the propositus and his affected relatives.167

Another dysfibrinogenemia involving amino acid D364, Melun I, was identified in a 40-year-old woman following a routine blood coagulation assay.168 The patient had no sign of hemorrhage or thrombosis at the time of the assay, but at 67 years of age the patient developed superficial venous thrombosis on her right foot. This was followed 2 years later by another episode of superficial venous thrombosis in her right leg. The propositus later had a stroke that did not cause long-term effects.168 Further tests eliminated other possible inherited causes of thrombophilia such as protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III deficiencies, or activated protein C (APC) resistance. The patient's mother, sisters, and brother all suffered from repeated deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary thromboembolic episodes. An exhaustive study of four generations showed that most, but not all, of the family members carrying the dysfibrinogenemia suffered from various forms of thrombosis, with episodes beginning as young as age 11. DNA sequencing of the three chains of fibrinogen Melun I led to the discovery of a D364V mutation.168 Again, two dysfibrinogenemias involving the same amino acid were associated with different phenotypes, one (D364H) devoid of symptoms and the other (D364V) associated with thrombophilia.

Two recent independent investigations showed the crucial role of D364 in the early stages of fibrin polymerization, ie, during the “A-a site” interaction.98,169 In the first study, the substitution D364A was introduced into the 30-kD fragment rFbgγC30 and, unlike the wild-type rFbgγC30, this mutant molecule (rFbgγC30-D364A) did not inhibit fibrinogen clotting. rFbgγC30 was protected against plasmin digestion by addition of the peptide GPRP or by calcium, as is the case for fibrinogen.170,171 The rFbgγC30-D364A mutant molecule was not protected by the peptide, suggesting that the “a” site is substantially altered in this mutant.98 In the second study, fibrin polymerization of recombinant, fully assembled fibrinogen containing the D364A and D364H mutations was significantly impaired, as expected if the “a” site is not functional.169 Fibrin polymerization of recombinant fibrinogen with the D364H mutation was almost undetectable. Clottability of the D364A mutant was essentially normal but that of the D364H mutant was substantially reduced. In fact, a fibrin gel did not form when the D364H-mutant fibrinogen was clotted.169 These data suggest that both protofibril formation and lateral aggregation were disrupted in the D364H mutant, indicating that the carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain plays a role in both polymerization steps.169

The crystal structures of rFbgγC30-GPRP56 and fragment D dimer-GPRPamide97 showed that the side chain of D364 forms a critical salt link with the charged amino terminus of the α-chain sequence GPR. The loss of the carboxylate group in the D364H and D364V mutations would eliminate an electrostatic bond that is crucial to the “A-a” interaction.

R375G.

Fibrinogen Osaka V was identified fortuitously in an asymptomatic 44-year-old woman.172 The polymerization of fibrin monomers was prolonged in the absence of calcium but normal polymerization occurred at 5 mmol/L CaCl2. Digestion of fibrinogen Osaka V fragment D by plasmin resulted in a more complete degradation of the molecule than was observed for normal fragment D. Further, equilibrium dialysis and Scatchard analysis showed that the mutant fibrinogen contained only one calcium-binding site, whereas three calcium sites have been found in normal fibrinogen.173-176

In the GPRP-complexed structures,56,97 the side chain of R375 forms hydrogen bonds that are critical for the stability of the polymerization pocket. The loss of this large side chain would drastically alter the shape and charge of this region. It would also remove an important salt link between R375 and D297. R375 is absolutely conserved among all the known γ chain sequences,55,97,99indicating the importance of this residue. The polymerization pocket appears to be biochemically98 and structurally56 97 distinct from the calcium-binding site. However, we suggest that the loss of the R375 side chain, which lines one side of the polymerization pocket, would exert a destabilizing effect on the entire region. This would explain the observed calcium-binding defect.

K380N.

Fibrinogen Kaiserslautern was identified in a 34-year-old woman who suffered from thrombosis in the cerebral sinus after a cesarean delivery, prior to which she had no history of bleeding or thrombosis.177 Her family included individuals who were homozygous as well as heterozygous for this defect, all of whom were asymptomatic. A K380N substitution was shown and glycosylation at N380, directed by the new consensus sequence (N-K-T), was confirmed.177

K380 is a surface-exposed residue, occurring at a site that is well removed from the polymerization pocket, the calcium-binding site, and the D:D interaction surfaces. Therefore, the polymerization defect is likely to be an altered packing of fibrils caused by the addition of an extra carbohydrate moiety.

FUNCTIONAL SITES WITHIN THE FIBRINOGEN γ CHAIN

In view of the biochemical, clinical, and structural information available to date on fibrinogen, at least five major functional sites can be distinguished within the globular carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain. These are: (1) the calcium-binding site; (2) the polymerization site “a”; (3) the D:D interaction surface; (4) the γ:γ crosslinking site; and (5) the platelet-binding site. Other functions have been reported to involve the γ chain of fibrinogen, such as t-PA binding, plasminogen binding, and interactions with cell-surface receptors; these await further characterization at the molecular level. Each of the five sites appears to function fairly independently from the others. However, a mutation at one site may destabilize the overall structure and thus affect function at a second site.

Calcium-binding site.

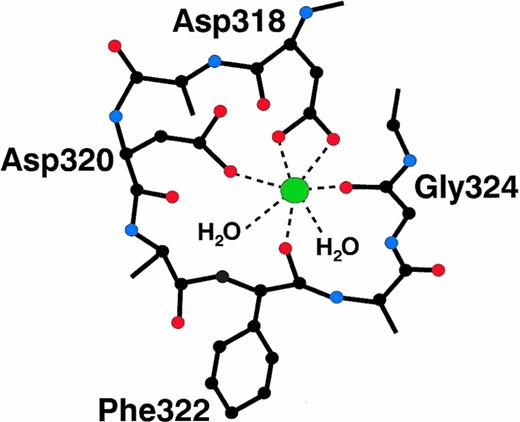

A single high-affinity calcium binding site has been found within fragment D,49,174-176,178 and localized to the globular carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain.51,52,55Figure3 presents a schematic of the interactions between the metal ion and the protein. The calcium ion is liganded by the side chains of D318 and D320, as well as by the backbone carbonyl oxygens of F322 and G324.55 Two water molecules provide the fifth and sixth coordinating ligands. Although fibrinogen can clot in the presence of EDTA, it does so less efficiently than in the presence of calcium.179 Thus, the calcium-bound conformation of the γ chain favors fibrin polymerization and protects this region from plasmin degradation.132 173 Two dysfibrinogens, Giessen IV (D318G) and Vlissingen I (ΔN319,D320), alter the calcium-binding site. These mutations disrupt the metal binding, and both of these dysfibrinogenemias correlate with a thrombotic tendency. Fibrinogen Osaka V (R375G) is also associated with altered calcium binding, presumably resulting from a regional disruption of the protein structure, but not with thrombosis.

Specific molecular interactions between the fibrinogen γ chain and the calcium ion. The calcium ion is liganded by two aspartate side chains, two carbonyl oxygen atoms, and two water molecules.55

Specific molecular interactions between the fibrinogen γ chain and the calcium ion. The calcium ion is liganded by two aspartate side chains, two carbonyl oxygen atoms, and two water molecules.55

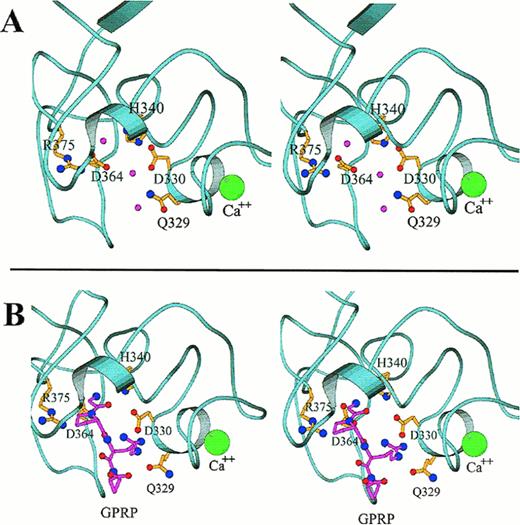

Close-up stereo views of the γ chain polymerization site “a” showing the interactions within the polymerization pocket for both the uncomplexed protein (A) and for the complex with GPRP (B), based on the rFbgγC30 structures. The mutation sites that affect the polymerization pocket are indicated in ball-and-stick representation. In (A), the water molecules that form hydrogen bonds with the displayed side chains are shown as pink spheres. In (B), the peptide GPRP is represented in pink. The calcium ion is shown in green, and is enlarged for emphasis.

Close-up stereo views of the γ chain polymerization site “a” showing the interactions within the polymerization pocket for both the uncomplexed protein (A) and for the complex with GPRP (B), based on the rFbgγC30 structures. The mutation sites that affect the polymerization pocket are indicated in ball-and-stick representation. In (A), the water molecules that form hydrogen bonds with the displayed side chains are shown as pink spheres. In (B), the peptide GPRP is represented in pink. The calcium ion is shown in green, and is enlarged for emphasis.

Space-filling model showing a close-up view of the γ:γ (or D:D) interface between adjacent molecules in the crosslinked D dimer complexed with the peptide GPRP (A). (Adapted and reprinted with permission from Nature [Spraggon G, Everse SJ, Doolittle RF: Crystal structures of fragment D from human fibrinogen and its crosslinked counterpart from fibrin. Volume 389, page 455, 1997].97 Copyright 1997 Macmillan Magazines Limited.) Space-filling (B) and ribbon (C) models of the globular carboxyl-terminal γ chain region, based on the rFbgγC30 structures (γ143-392). Mutation sites at the γ:γ interface are colored orange (B and C), the calcium ion is green, and the peptide GPRP is shown in magenta. The side chains of residues F303 and F304 are shown in white. We hypothesize that these residues may form part of an extended interaction surface between the D and E regions of fibrin. Residues G292, S358, and K380 are also shown; G268 and G292 are indicated by asterisks (C).

Space-filling model showing a close-up view of the γ:γ (or D:D) interface between adjacent molecules in the crosslinked D dimer complexed with the peptide GPRP (A). (Adapted and reprinted with permission from Nature [Spraggon G, Everse SJ, Doolittle RF: Crystal structures of fragment D from human fibrinogen and its crosslinked counterpart from fibrin. Volume 389, page 455, 1997].97 Copyright 1997 Macmillan Magazines Limited.) Space-filling (B) and ribbon (C) models of the globular carboxyl-terminal γ chain region, based on the rFbgγC30 structures (γ143-392). Mutation sites at the γ:γ interface are colored orange (B and C), the calcium ion is green, and the peptide GPRP is shown in magenta. The side chains of residues F303 and F304 are shown in white. We hypothesize that these residues may form part of an extended interaction surface between the D and E regions of fibrin. Residues G292, S358, and K380 are also shown; G268 and G292 are indicated by asterisks (C).

Polymerization site “a.”

The localization of the primary polymerization site “a” to the carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain was established several years ago.49,50,52,54 The “a” site binds the GPR sequence that is exposed upon the release of fibrinopeptide A from the α chain, and several short peptides having sequences related to GPR also bind to the “a” site.12,180-182 The peptides GPRP and GPRP-amide bind to the γ chain of fragment D with an affinity that actually exceeds that of the peptide having the native sequence, GPRV.182 In addition, the peptide GPRP protects the γ chain of fragment D against plasmic degradation, even in the presence of EDTA.63,98 170 Figure 4 shows in detail some of the important molecular interactions at the polymerization site before and after binding to the GPRP sequence.

Several dysfibrinogens involve mutations of γ-chain residues that either bind to the GPR sequence directly, or that constitute the architecture of the polymerization site. These include Fibrinogens Nagoya I (Q329R), Milano I (D330V), Kyoto III (D330Y), Bern I (N337K), Matsumoto I (D364H), Melun I (D364V), and Osaka V (R375G).

D:D interaction surface.

During the alignment of the fibrin monomers into fibrils (Fig 1), surface-exposed regions on the γ chains of two adjacent molecules abut each other and form the D:D interface (Fig 5A). The γ-γ (or D:D) interface is extensive,97 and encompasses a number of amino acids that are substituted in dysfunctional fibrinogens (Fig 5B andC). These dysfibrinogens include Fibrinogens Kurashiki I (G268E), Baltimore IV, Bellingham I, Bologna I, Milano V, Morioka I, Osaka II, Tochigi I, Tokyo II, and Villajoyosa I (R275C), Barcelona III and IV, Bergamo II, Claro I, Essen I, Haifa I, Osaka III, Perugia I, and Saga I (R275H), Japanese I (R275S), Baltimore III (N308I), Bicêtre I, Kyoto I, and Matsumoto II (N308K), and Asahi I (M310T). Disruption of this γ:γ interaction has been hypothesized to disrupt the fibrin alignment.100,101 Scanning electron microscopic images of fibrin Tokyo II (Fig 6) show unequivocally that the structure of the fibrin clot was altered drastically by a mutation at the γ:γ interface, R275C.100

Scanning electron micrograph images of Tokyo II fibrin (γR275C) (A and B) and normal fibrin (C and D). Fibrin formed in HEPES pH 7 buffer (A and C) and formed in the same buffer containing 10 mmol/L CaCl2. (Reproduced from The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1995, vol. 96, p. 1053, by copyright permission of The American Society for Clinical Investigation.100)

Scanning electron micrograph images of Tokyo II fibrin (γR275C) (A and B) and normal fibrin (C and D). Fibrin formed in HEPES pH 7 buffer (A and C) and formed in the same buffer containing 10 mmol/L CaCl2. (Reproduced from The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1995, vol. 96, p. 1053, by copyright permission of The American Society for Clinical Investigation.100)

We also note that F303 and F304 form a surface patch on the γ chain that could interact favorably with a hydrophobic patch on the surface of another molecule, and that these residues lie between the γ:γ surface and the polymerization pocket (Fig 5B). Therefore, F303 and F304 could potentially be involved in D:E and/or D:D interactions.

γ-γ crosslinking site.

Factor XIIIa catalyzes reciprocal covalent crosslinks between the glutamine donors Q398 and/or Q399 of one molecule and the lysine acceptor K406 of an adjacent fibrin(ogen) molecule.22,183 184 There are no reported dysfibrinogenemias associated with mutations in this region of the γ chain (also referred to as γXL:γXL). Such mutants would likely be “silent” in standard thrombin time assays, and this may explain why they have not been reported in the literature.

Platelet-binding site.

Fibrinogen interacts with the platelet receptor GPIIbIIIa through the last several amino acids at the carboxyl end of the γ chain.57-59,185,186 Although other regions may interact with this receptor as well, the sequence γ408-411 (AGDV) is absolutely required for fibrinogen binding.60 The interaction with platelets has also been visualized through electron microscopic studies.187 Crystallographic studies have not shown a unique conformation for the carboxyl-terminal 19 residues of the γ chain. In the rFbgγC30 protein preparations, this region was very susceptible to proteolysis.55 The gaps in interpretable electron density in some of the crystal structures of this molecule were likely caused by heterogeneity at the carboxyl terminus, and it is probable that this region also has some inherent flexibility.

γ-CHAIN DYSFIBRINOGENEMIAS ASSOCIATED WITH BLEEDING

In general, mutations within the γ chain of fibrinogen are not associated with serious bleeding disorders. Two patients, Baltimore I (G292V) and Giessen IV (D318G), who experienced mild bleeding symptoms, also suffered from thrombotic tendencies. The only γ-dysfibrinogenemia associated with a serious bleeding diathesis is Asahi I (M310T). In this instance, the bleeding symptoms were probably related to the extra glycosylation resulting from the substitution. As discussed earlier, hypoglycosylation increases the rate and extent of clotting.150 Therefore, one can speculate that hyperglycosylation could decrease the clotting rate and thereby cause a bleeding disorder. The molecular explanation would be that the charged carbohydrates lead to a repulsive force between adjacent molecules, thus hindering the assembly and polymerization of fibrin. Also, the bulkiness of the extra carbohydrate could preclude the proper alignment of the fibrin chains.

γ-DYSFIBRINOGENEMIAS ASSOCIATED WITH THROMBOSIS

The proposed mechanisms by which abnormal fibrinogens may contribute to a thrombotic tendency are numerous.80,84 For example, an increased resistance of the mutant fibrin to plasmin proteolysis may arise from alterations in the clot structure and permeability. These mutations may restrict the accessibility of fibrin to plasmin.96,188,189 Other mutations may reduce fibrin-mediated enhancement of fibrinolysis by altering the binding of plasminogen or t-PA to fibrin.190,191 For the γ-dysfibrinogenemias, the most probable reason for the association of mutations with thrombophilia is an altered clot structure. In heterozygous individuals, fibrin polymerization is perturbed but functional, leading to clots with abnormal fiber thickness and porosity. As fibrin structure has been shown to influence the fibrinolytic rate,192 these clots may not be dissolved effectively by the fibrinolytic system, resulting in an increased tendency to thrombosis. We speculate that many of these mutations, if present in the homozygous state, would cause bleeding disorders as well.

DYSFIBRINOGENEMIA AS A HYPERCOAGULABLE STATE

Thrombosis is a major cause of mortality and morbidity. The risk factors for thrombosis can be transient or permanent, acquired, congenital, or inherited. Among the identified inherited risks factors associated with thrombophilia are protein C, protein S, antithrombin III, and heparin cofactor II deficiencies; factor Va resistance to APC; thrombomodulin defects; factor II 20210 allele; and hypoplasminogenemia.79,80,83,85,86,193 194 However, taken together, these conditions account for only 40% to 60% of all familial thrombophilias.

Dysfibrinogenemias are also recognized as possible risk factors for thrombosis. The majority of diagnosed individuals are asymptomatic, whereas approximately 30% of dysfibrinogenemias are associated with bleeding and ≈10% are associated with thrombotic tendencies. However, if one considers only dysfibrinogenemias with mutations in the carboxyl-terminal region of the γ chain, then the distribution changes considerably. An examination of the clinical symptoms associated with γ-dysfibrinogenemias shows that ≈5% (2 of 37) of the individuals experienced significant bleeding, and ≈30% (11 of 37) showed thrombotic tendencies. Approximately 60% (23 of 37) of patients with γ-dysfibrinogenemias were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Although an association is found between certain dysfibrinogenemias and specific symptoms, a direct causal relationship is difficult to demonstrate. Often, the investigation of other risk factors was omitted, incomplete, or not reported. Furthermore, the family history for these mutations, which can be difficult to gather, was often not documented. Unfortunately, data on long-term follow-up of dysfibrinogemic patients and their relatives are rarely available.

Typically, dysfibrinogenemias are discovered fortuitously during routine coagulation tests. At present, there is no practical, simple, and cost-effective clinical test that could allow the diagnosis of thrombophilic dysfibrinogenemias that do not affect fibrin polymerization. One must consider the possibility that mutant dysfibrinogens exist that affect fibrinolysis but not fibrin polymerization. If these dysfibrinogenemias exist, then thrombosis-associated dysfibrinogenemias are surely underdiagnosed, and these may represent a more important determinant of hereditary hypercoagulable states than is generally recognized.

A relatively small number of the diagnosed dysfibrinogenemias have been characterized at the molecular level. Numerous others that are associated with mild to severe familial thrombosis still await characterization at the molecular level. These include fibrinogens Date I,191 Richfield,195 Tampere I,196and London I.197 198

It has been suggested that an inherited predisposition to thrombosis is often the result of mutations in two or more genes encoding proteins involved in hemostasis.79 Similarly, a γ-dysfibrinogenemia may well act in concert with other risk factors such as stasis, surgery, pregnancy, trauma, lupus, malignancy, oral contraceptives, hyperhomocysteinemia, or elevated factor VIII or fibrinogen levels. Such combinations could trigger the occurrence of a thrombotic episode in an otherwise healthy individual. Examples illustrating this phenomenon would be the heterozygous dysfibrinogemias Cedar Rapids (R275C)122 and Giessen IV (D318G),84 both of which were found in conjunction with a heterozygous factor V Leiden trait. In the Cedar Rapids family, neither defect alone was associated with symptoms, but the double phenotype was strongly associated with pregnancy-related thrombophilia. The complex interactions between potential risk factors would explain to some degree the variability observed in the clinical symptoms associated with γ-dysfibrinogenemias. In the case of the R275, N308, and D364 mutants, the clinical manifestations associated with a given molecular defect varied greatly from one patient to another. A mutation associated with mild hemorrhage in one patient may appear to be silent in another, and yet may be associated with severe thrombophilia in another individual.

Finally, the analysis of the various fibrinogen γ chain mutants is complicated by many factors. First, most dysfibrinogens were identified in heterozygous individuals; therefore, the circulating fibrinogen is a heterozygous mixture of normal and mutant molecules. Second, apart from commonly used assays such as thrombin time and fibrinopeptide release, the biochemical characterization of these defects has not been standardized. Experiments are performed using different protocols, on plasma in some cases, and on purified fibrinogen in others, under varying conditions. This situation complicates the direct comparison of results from different laboratories, and may explain some of the apparent discrepancies between the observed effects of a given molecular defect.

CONCLUSIONS

As proposed in the fibrinogen subcommittee study,84 it would be valuable, in approaching a case of thrombophilic dysfibrinogenemia, to evaluate all other known contributing risk factors and to rigorously document the family history. This would help determine if the diagnosed dysfibrinogenemia is the sole thrombotic risk factor present. The same analysis should be performed for patients with bleeding symptoms and for asymptomatic individuals, if we are to determine with any degree of certainty the influence of the dysfibrinogenemia on the long-term manifestations of these defects. Finally, every effort should be made to accurately establish the diagnosis of a thrombosis. By combining well-documented family histories with correct diagnoses of symptoms, the possible associations between the various dysfibrinogenemias and thrombosis can then be assessed more accurately.

The recent determination of several crystal structures of fibrinogen fragments has shed light on the arrangement of domains at the distal nodules of fibrinogen, the architecture of the “a” polymerization pocket, and the interactions between amino acid residues that are critical for the various functions of this fascinating and complex molecule. As an early outgrowth of this work, the effects of mutations that cause dysfibrinogenemias can now be explored through further structure-function studies. Hypotheses originating from a consideration of the patients' symptoms and from an examination of the fibrinogen structure can now be explored and refined by experiments using recombinant protein expression systems. We expect that future studies will lead to a broader overall understanding of fibrinogen and its pathologies, and hopefully to improvements in the diagnosis and management of dysfibrinogenemic patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Drs E.W. Davie, D.W. Chung, and F. Haverkate for critical reading of the manuscript. We are also grateful to Dr B. Stoddard for access to computing resources and to Jeff Harris for technical assistance. We thank Dr M. Mosesson for providing us with the EM photographs and for helpful comments, and Dr R.F. Doolittle and coworkers for permission to reproduce Fig 5A.

The coordinates of the various fibrinogen fragment crystal structures are available from the Brookhaven Data Bank, http://www.pdb.bnl.gov, with accession nos. 1FIB, 2FIB, 3FIB, 1FZA, and 1FZB.

Supported in part by National Institute of Health Grants No. HL31048 (to S.T.L.) and HL16919. H.C.F.C. was supported in part by a Research Fellowship from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Address reprint requests to Kathleen P. Pratt, PhD, Department of Biochemistry, Box 357350, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; 98195; e-mail: kpratt@u.washington.edu.

![Fig. 5. Space-filling model showing a close-up view of the γ:γ (or D:D) interface between adjacent molecules in the crosslinked D dimer complexed with the peptide GPRP (A). (Adapted and reprinted with permission from Nature [Spraggon G, Everse SJ, Doolittle RF: Crystal structures of fragment D from human fibrinogen and its crosslinked counterpart from fibrin. Volume 389, page 455, 1997].97 Copyright 1997 Macmillan Magazines Limited.) Space-filling (B) and ribbon (C) models of the globular carboxyl-terminal γ chain region, based on the rFbgγC30 structures (γ143-392). Mutation sites at the γ:γ interface are colored orange (B and C), the calcium ion is green, and the peptide GPRP is shown in magenta. The side chains of residues F303 and F304 are shown in white. We hypothesize that these residues may form part of an extended interaction surface between the D and E regions of fibrin. Residues G292, S358, and K380 are also shown; G268 and G292 are indicated by asterisks (C).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/92/7/10.1182_blood.v92.7.2195/3/m_blod419cot05z.jpeg?Expires=1765889164&Signature=gHfS5OcjEs30pgjdpttJ~Teyq1~dUoZpNnmVY6I-teN81nag6k2bk6IyirePVRMk3e5Fm2IQ~09T~0WNnoDuLIEsY121XRwNESnS8oTqdUVp6-KMBze~mhP9T4JE19773keAraEZTamN1~ts395t0q-xAhznkA0tvrx24aM8AB7cx~Fqij4umP91MMs9Yt9CpXbTUqDhzXxDrXHeG8k7gDDPaFIHUNLbkwZT0tgJoPz-6II0nNQfIKlOVaGZUE3wpiPurpj8qvEKTpN-ChS1VCoEvim8zSFsCXftQMS5EA65LGJ5g040mmjKfQ-jpmvprPjxczDvp-XLIRxHy233Gg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal