Abstract

The helix-loop-helix transcription factor SCL (TAL1) is indispensable for blood cell formation in the mouse embryo. We have explored the localization and developmental potential of cells fated to express SCL during murine development using SCL-lacZmutant mice in which the Escherichia coli lacZreporter gene was ‘knocked in’ to the SCL locus. In addition to the hematopoietic defect associated with SCL deficiency, the yolk sac blood vessels in SCLlacZ/lacZ embryos formed an abnormal primary vascular plexus, which failed to undergo subsequent remodeling and formation of large branching vessels. Intraembryonic vasculogenesis in precirculationSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos appeared normal but, in embryos older than embryonic day (E) 8.5 to E9, absolute anemia leading to severe hypoxia precluded an accurate assessment of further vascular development. In heterozygous SCLlacZ/w embryos, lacZ was expressed in the central nervous system, vascular endothelia, and primitive and definitive hematopoietic cells in the blood, aortic wall, and fetal liver. Culture of fetal liver cells sorted for high and low levels of β galactosidase activity fromSCLlacZ/w heterozygous embryos indicated that there was a correlation between the level of SCL expression and the frequency of hematopoietic progenitor cells.

THE HELIX-LOOP-HELIX transcription factorSCL (TAL1) was initially cloned as a partner in the t(1;14) translocation, which characterized certain human T-cell leukemias.1 It was subsequently shown to be indispensable for blood cell formation in the mouse because SCL-deficient embryos displayed an absolute anemia, which resulted in retarded growth by 9 days of gestation (E9) and death by E9.5 to 10.5.2,3SCL was also critically required for the development of hematopoiesis in the adult mouse4,5 and for the induction of hematopoietic genes during embryonic stem cell differentiation.6

Complementary studies examining the expression pattern of SCLin hematopoietic populations in mice and humans demonstrated selective expression in primitive CD34+ cells and in erythroid, megakaryocytic, and mast cell lineages.7-11SCLexpression decreased as CD34+ cells differentiated into myeloid cells and analyses of SCL expression in erythroid colonies showed more abundant expression in colonies at early timepoints during their development.9,11-14 Consistent with these observations, retroviral transfer of SCL into human hematopoietic precursors preferentially enhanced erythroid and megakaryocytic colony formation.15 16

These data have spawned a model in which SCL is portrayed as a ‘master regulator of hematopoiesis’17 and lies at the apex of a pyramid of transcription factors controlling hematopoietic lineage commitment.18 Of course, this view of the role ofSCL may be oversimplified, as the complete molecular program of hematopoietic commitment is likely to require a complex, interdependent network of regulatory genes. Indeed, it has been shown that SCL can form a multiprotein complex in hematopoietic cells, which includes the transcription factors E2A and GATA-1, linked by the transcription factor binding proteins LMO2 and Ldb-1.19 It is instructive that the extreme phenotype displayed by SCL knockout embryos is recapitulated in LMO2 knockout mice,20 21 but not in animals targeted at the other loci. This implies that SCL is critical for the expression of genes needed to initiate hematopoiesis, that a multiprotein complex is required (hence the need for the bridging protein LMO2), but that the other known components of this complex are at least partly redundant at this stage.

Although the gene ablation and gene expression studies provided strong circumstantial evidence for the role of SCL as a hematopoietic stem cell regulator, a functional correlation between endogenousSCL expression and progenitor cell activity in adult hematopoietic cells was first provided by the analysis of mice in which the Escherichia coli lacZ reporter gene had been “knocked in” to the SCL locus (SCL-lacZmice).22 This analysis indicated that SCL was expressed in all of the progenitors examined, including day 12 spleen colony-forming cells (CFCs) and progenitors for erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid lineages. Thus, hematopoietic cells could be stratified into functional groups based on their expression of a developmentally relevant transcription factor.

To further define the role of SCL in embryogenesis, we have examined the expression pattern of β galactosidase during development in both heterozygous (SCLlacZ/w) andSCL-null (SCLlacZ/lacZ) SCL-lacZmutant mice. These studies showed abnormalities in vascular development, which were more severe in the yolk sac than in the embryo in early SCLlacZ/lacZ embryos. Examination of mid- and later-gestation SCLlacZ/w heterozygous embryos demonstrated SCL expression in hematopoietic, vascular, and neural tissues. Culture of fetal liver cells sorted for high and low levels of β galactosidase activity from SCLlacZ/wheterozygous embryos indicated that there was a correlation between the level of SCL expression and progenitor cell activity in the embryo, as well as in the adult mouse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SCL-lacZ mice.

The generation of SCL-lacZ mice has been described previously.22 As a consequence of this “knock-in” strategy, all SCL coding sequences were deleted and expression of the lacZ gene is controlled by SCL regulatory elements.

Histochemical staining for β galactosidase activity.

Embryos were fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde (E7.5 to E11.5) or 0.2% glutaraldehyde/1% formaldehyde (>E12.5) in wash buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS])/2 mmol/L MgCl2/5 mmol/L EGTA/ 0.02% NP-40/0.01% sodium deoxycholate) for 60 minutes on ice. The yolk sac and amnion were opened and the roof of the fourth ventricle and the abdomen were pierced in older embryos to improve access of solutions. Embryos were washed 3 times for 30 minutes at room temperature in wash buffer and incubated overnight at 37°C in staining solution (100 mmol/L NaPO4, pH 7.3/5 mmol/L K4 Fe(CN)6 .3H2O/5 mmol/L K3 Fe(CN)6/2 mmol/L MgCl2/5 mmol/L EGTA/0.02% NP-40/0.01% sodium deoxycholate/0.6 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside [X-gal]). Stained embryos were washed twice for 5 minutes in PBS/3% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at 4°C. Fetal livers and brains were dissected from embryos for whole organ staining, fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde in wash buffer for 40 minutes on ice, washed, and stained as above. Histological sections of paraffin-embedded lacZ stained embryos and tissues were counterstained with nuclear fast red. In some cases, embryos were fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde/PBS for 30 minutes, infiltrated with 30% sucrose/PBS, embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and frozen. Frozen sections were washed and stained for lacZ as above.

Immunohistochemistry.

Whole-mount staining of embryos and yolk sacs with anti–PECAM-1 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1) monoclonal antibody (MEC13.3; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) was performed as described.23 Stained embryos were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and counterstained with nuclear fast red.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-Gal analysis.

The FACS-Gal assay was performed essentially as described.24 Fetal livers from E11.5 to E18.5SCLlacZ/w mice or their wild-type littermates were dissociated by triturating into 300 μL of PBS supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS). The cells were washed once with the same solution and resuspended in 20 to 300 μL of PBS/5%FCS and warmed to 37°C. Hypotonic loading was accomplished by diluting the cells 1:1 with warmed 2 mmol/L fluorescein di-β-D-galactopyranoside (FDG) (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO) and incubating at 37°C for 2 minutes. Loading was stopped by adding 10 vol ice-cold PBS/5%FCS and intracellular hydrolysis of FDG to fluorescein by β galactosidase was allowed to proceed on ice for 3 hours. Propidium iodide was added to a final concentration of 1 μg/mL before analysis. Cells were analyzed and sorted on a FACStar Plus (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Clonogenic assays for hematopoietic progenitors.

Fractionated and unfractionated E12.5 fetal liver cells fromSCLlacZ/w mice or their wild-typeSCLw/w littermates were cultured in 0. 9% methylcellulose for myeloid and erythroid colony formation as described.25 The number of cells cultured for each fraction was titrated to produce approximately 100 colonies per 1 mL culture at day 7. Day 7 myeloid and day 7 blast-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E) colonies were stimulated by the combination of 1,000 U/mL interleukin-3 (IL-3) and 4 U/mL human erythropoietin (Epo) and day 2 colony-forming unit-erythroid (CFU-E) colonies by 4 U/mL human Epo. CFU-E were scored using an inverted microscope and day 7 colonies were scored using a dissection microscope.26

RESULTS

Abnormal intraembryonic and yolk sac vessel formation inSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos.

In SCL-lacZ embryos, expression of lacZ was detected at embryonic day (E)7.5 in the extraembryonic mesoderm (Fig 1A and B) in a speckled pattern reminiscent of FLK-1 expression27 and consistent with the previously demonstrated expression of SCLin the mesodermal precursors of yolk sac blood islands.28 29 At this stage of development, homozygousSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos, which were destined to die due to absolute anemia by E9.5, were indistinguishable from developmentally normal SCLlacZ/w heterozygotes.

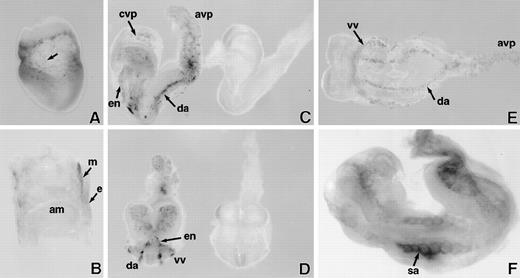

LacZ staining of whole mount E7.5 to 8.5 days postcoitum (dpc) SCLlacZ/lacZembryos. (A) E7.5 embryo showing speckled staining (arrow) in the yolk sac. (B) Sagittal section of E7.5 embryo indicating that lacZ staining is confined to the extraembryonic mesoderm (m); endoderm (e); amnion (am). (C) Lateral and (D) anterior views of early somite (E8) embryos demonstrating specific lacZ staining of vascular structures inSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos (left). No staining is seen inSCLw/w fetuses (right); cvp, cerebral vascular plexus; avp, allantoic vascular plexus; en, endocardium; da, dorsal aorta. (E) Ventral view of early somite (E8.0)SCLlacZ/lacZ embryo, demonstrating migration and alignment of angioblasts to form the dorsal aorta (da), allantoic vascular plexus (avp), and the vitelline vein (vv), which receives blood from the yolk sac. (F) E8.5 embryo showing the somitic arteries (sa) sprouting from the dorsal aorta.

LacZ staining of whole mount E7.5 to 8.5 days postcoitum (dpc) SCLlacZ/lacZembryos. (A) E7.5 embryo showing speckled staining (arrow) in the yolk sac. (B) Sagittal section of E7.5 embryo indicating that lacZ staining is confined to the extraembryonic mesoderm (m); endoderm (e); amnion (am). (C) Lateral and (D) anterior views of early somite (E8) embryos demonstrating specific lacZ staining of vascular structures inSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos (left). No staining is seen inSCLw/w fetuses (right); cvp, cerebral vascular plexus; avp, allantoic vascular plexus; en, endocardium; da, dorsal aorta. (E) Ventral view of early somite (E8.0)SCLlacZ/lacZ embryo, demonstrating migration and alignment of angioblasts to form the dorsal aorta (da), allantoic vascular plexus (avp), and the vitelline vein (vv), which receives blood from the yolk sac. (F) E8.5 embryo showing the somitic arteries (sa) sprouting from the dorsal aorta.

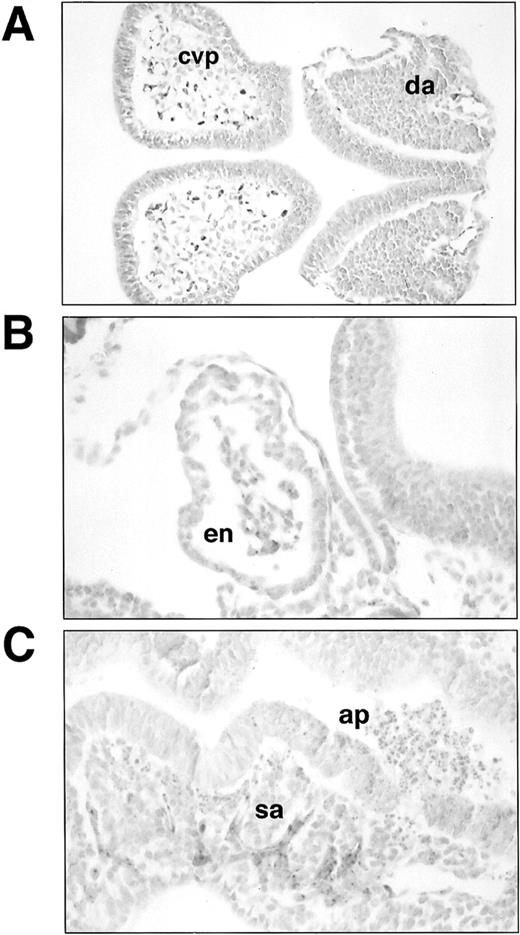

Histological sections of lacZ-stainedSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos. (A) Section through headfold and trunk of E8 embryo showing lacZ staining in the angioblasts forming the cerebral vascular plexus (cvp) and the dorsal aorta (da). Staining in (B) endocardium (en) and (C) somitic arteries (sa) in an E8.5 embryo. Note the large number of apoptotic cells (ap) in the neural tube in (C). Original magnification: (A), ×200; (B and C), ×400.

Histological sections of lacZ-stainedSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos. (A) Section through headfold and trunk of E8 embryo showing lacZ staining in the angioblasts forming the cerebral vascular plexus (cvp) and the dorsal aorta (da). Staining in (B) endocardium (en) and (C) somitic arteries (sa) in an E8.5 embryo. Note the large number of apoptotic cells (ap) in the neural tube in (C). Original magnification: (A), ×200; (B and C), ×400.

In early somite stage (≈E8) homozygousSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos, β galactosidase was expressed in the primitive heart and the cells lining the dorsal aorta and the cerebral and allantoic vascular plexuses (Fig 1C through E). Microscopic examination of sections of stained embryos confirmed that lacZ expression was confined to the endocardium and endothelia (Fig 2A and B). Consistent with previous observations,2 3 these data confirmed that SCL was dispensable for embryonic vasculogenesis, the specification of angioblasts from ventral mesoderm, their appropriate migration within the embryo, and alignment to form major vascular structures. Development in the majority ofSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos continued until E9, by which time the embryos had a beating heart and had turned. As shown in Fig1F, lacZ expression now also marked the somitic arteries sprouting from the dorsal aorta, indicating that there was no intrinsic failure of angiogenesis. These vessels are shown histologically in Fig 2C. Marked regions of neuronal cell death were already evident by this time, presumably secondary to hypoxia.

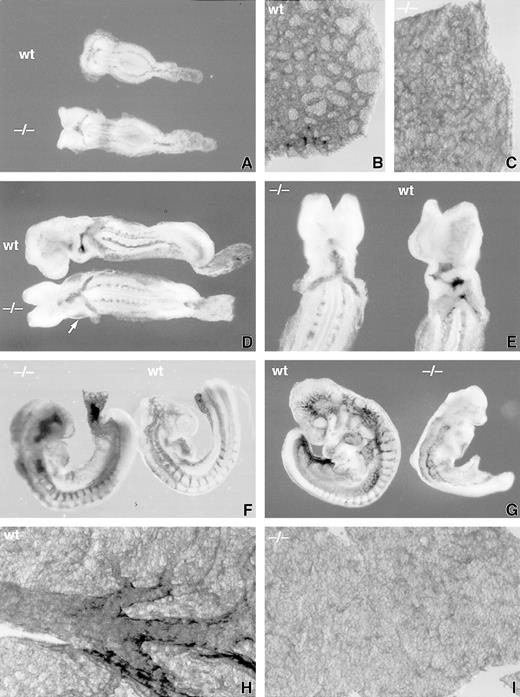

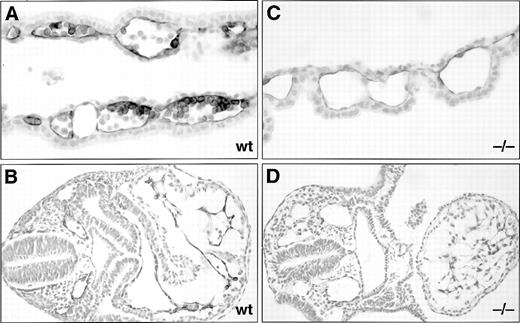

Although lacZ expression was readily detectable in homozygousSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos, staining for lacZ expression in SCLlacZ/w heterozygous embryos during early development was weak, probably because the SCL promoter directed a low level of transcription and only 1 copy of thelacZ gene was present. Therefore, the appearance of the developing embryonic vasculature in wild-type (SCLw/w and SCLlacZ/w) andSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos was directly compared using an antibody to the highly expressed endothelial surface marker PECAM-1 (CD31).30 In early somite embryos, the pattern of PECAM-1 staining of the nascent intraembryonic vasculature was very similar in wild-type and homozygous SCLlacZ/lacZ embryos (Fig 3A). This was identical to the pattern of lacZ expression observed inSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos of a similar developmental stage (compare Fig 3A with Fig 1E). In contrast, vascular development in the yolk sac was markedly abnormal inSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos by E8, earlier than had been reported previously.2,31 While wild-type embryo yolk sacs harbored a well-developed, clearly demarcated primary vascular plexus,SCLlacZ/lacZ yolk sacs contained only a disorganized network of fine vascular channels (compare Fig 3C with 3B). By the 10 somite stage, PECAM-1 expression was reduced in the dorsal aorta and the cerebral vascular plexus ofSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos (Fig 3D). In wild-type embryos, cardiac looping had commenced, but inSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos, the heart was still a straight tube and there was considerable pericardial edema (Fig 3D and E). Consistent with the lacZ staining shown in Fig 1F, PECAM-1 expression was evident in the forming somitic arteries at E9 inSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos (Fig 3F). Even though intraembryonic cell death was already widespread histologically by E9 (Fig 2C), marked growth retardation and vascular degeneration inSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos did not become grossly apparent until E9.5 (Fig 3G). The yolk sac vessels in these embryos had failed to develop significantly from their disorganized state at E8, while large PECAM-1–positive vascular trunks were prominent in wild-type yolk sacs (compare Fig 3B and C with Fig 3H and I). In histological sections of these embryos, PECAM-1 staining in the yolk sac was apparent in the endothelium and a subset of the hematopoietic cells in the blood islands in wild-type E8.5 (≈10 somite stage) embryos32(Fig4A), while expression was limited to the endothelium in the bloodless channels of the SCLlacZ/lacZ yolk sacs (Fig 4C). The complex cardiac looping and clearly defined vasculature of the normal embryo contrasted with the linear heart and dilated dorsal aorta, cardinal, and perineural veins displayed by theSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos (Fig 4B and D).

Anti–PECAM-1 monoclonal antibody staining of wholemount E8 to 9.5 dpc wild-type (wt) and SCLlacZ/lacZ(−/−) embryos and yolk sacs. (A) through (C) E8 embryos showing a similar pattern of anti–PECAM-1 staining in wt and −/− embryos (A), but a poorly formed primary vascular plexus in the −/− yolk sac (C) compared with the wt yolk sac (B). (D) and (E) At E8.5, somitic arteries are beginning to develop from the dorsal aorta. A dilated pericardial sac (arrowed), delayed cardiac looping, and diminished cerebral vasculature are evident in the −/− embryo. The pericardial sac was dissected away in (E) to display anti–PECAM-1 staining in the endocardium. (F) E9 embryos showing incomplete somitic vessels in the −/− embryo, which is undergoing apoptosis. (G) Preterminal, severely growth-retarded E9.5 mutant embryo (−/−) displaying loss of vascular architecture. (H) Large branching vitelline vessels in wt yolk sac at E9.5 contrast with the −/− yolk sac (I), which retains a poorly formed capillary plexus.

Anti–PECAM-1 monoclonal antibody staining of wholemount E8 to 9.5 dpc wild-type (wt) and SCLlacZ/lacZ(−/−) embryos and yolk sacs. (A) through (C) E8 embryos showing a similar pattern of anti–PECAM-1 staining in wt and −/− embryos (A), but a poorly formed primary vascular plexus in the −/− yolk sac (C) compared with the wt yolk sac (B). (D) and (E) At E8.5, somitic arteries are beginning to develop from the dorsal aorta. A dilated pericardial sac (arrowed), delayed cardiac looping, and diminished cerebral vasculature are evident in the −/− embryo. The pericardial sac was dissected away in (E) to display anti–PECAM-1 staining in the endocardium. (F) E9 embryos showing incomplete somitic vessels in the −/− embryo, which is undergoing apoptosis. (G) Preterminal, severely growth-retarded E9.5 mutant embryo (−/−) displaying loss of vascular architecture. (H) Large branching vitelline vessels in wt yolk sac at E9.5 contrast with the −/− yolk sac (I), which retains a poorly formed capillary plexus.

Histological sections of anti–PECAM-1 monoclonal antibody-stained E8.5 dpc wt and SCLlacZ/lacZ(−/−) embryos and yolk sacs. Anti–PECAM-1 stains both the endothelium and a subset of the hematopoietic cells in a wt yolk sac (A), but is restricted to the endothelium in the −/− yolk sac (C). (B) Section through the trunk of a wt embryo showing anti–PECAM-1 staining of the endocardium and endothelia. (D) In the −/− embryo, the anti–PECAM-1 antibody recognizes the endocardium of a more linear heart tube and dilated intraembryonic vessels. Original magnification: (A and C), ×400; (B and D), ×200.

Histological sections of anti–PECAM-1 monoclonal antibody-stained E8.5 dpc wt and SCLlacZ/lacZ(−/−) embryos and yolk sacs. Anti–PECAM-1 stains both the endothelium and a subset of the hematopoietic cells in a wt yolk sac (A), but is restricted to the endothelium in the −/− yolk sac (C). (B) Section through the trunk of a wt embryo showing anti–PECAM-1 staining of the endocardium and endothelia. (D) In the −/− embryo, the anti–PECAM-1 antibody recognizes the endocardium of a more linear heart tube and dilated intraembryonic vessels. Original magnification: (A and C), ×400; (B and D), ×200.

LacZ staining in the central nervous system of heterozygous (SCLlacZ/w) embryos. (A and B) At E11.5, lacZ staining is apparent in the presumptive motor neurons in the ventral neural tube (arrows). (C) Lateral and (D) dorsal views at E12.5 and (E) lateral and (F) dorsal views at E13.5, showing expression of lacZ in the developing midbrain. At E18.5 (G) and (H) and in the adult mouse (I and J), lacZ expression is strongest in the superior colliculi, but lower levels persist in the inferior colliculi. Weak lacZ expression is evident in tracts on the ventral surface of the hindbrain (H) and (J).

LacZ staining in the central nervous system of heterozygous (SCLlacZ/w) embryos. (A and B) At E11.5, lacZ staining is apparent in the presumptive motor neurons in the ventral neural tube (arrows). (C) Lateral and (D) dorsal views at E12.5 and (E) lateral and (F) dorsal views at E13.5, showing expression of lacZ in the developing midbrain. At E18.5 (G) and (H) and in the adult mouse (I and J), lacZ expression is strongest in the superior colliculi, but lower levels persist in the inferior colliculi. Weak lacZ expression is evident in tracts on the ventral surface of the hindbrain (H) and (J).

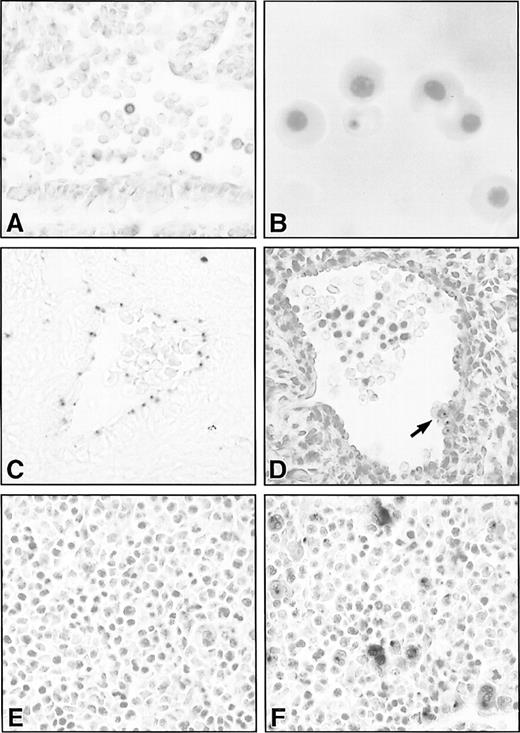

Histological sections of lacZ-stained hematopoietic and vascular tissues in SCLlacZ/w embryos. (A) Sagittal section through the dorsal aorta of an E9.5 embryo demonstrating lacZ staining of variable intensity in circulating hematopoietic cells. (B) Cytocentrifuge preparation of E13.5 embryonic blood showing lacZ staining in a definitive erythrocyte. (C) Endothelial lacZ expression in a cerebral artery of an E13.5 embryo. (D) The dorsal aorta of an E11.5 embryo demonstrating lacZ staining in the endothelium and in a ventral aortic wall cluster of hematopoietic cells (arrow). All the cells in the cluster were positive, but this cannot be appreciated in a single focal plane. (E) and (F) LacZ staining in E11.5 fetal liver of a wt (E) and heterozygous SCLlacZ/w embryo (F) showing specific staining in large megakaryocytes and smaller erythroblasts. Original magnification: (A, C through F), ×400; (B), ×1,000.

Histological sections of lacZ-stained hematopoietic and vascular tissues in SCLlacZ/w embryos. (A) Sagittal section through the dorsal aorta of an E9.5 embryo demonstrating lacZ staining of variable intensity in circulating hematopoietic cells. (B) Cytocentrifuge preparation of E13.5 embryonic blood showing lacZ staining in a definitive erythrocyte. (C) Endothelial lacZ expression in a cerebral artery of an E13.5 embryo. (D) The dorsal aorta of an E11.5 embryo demonstrating lacZ staining in the endothelium and in a ventral aortic wall cluster of hematopoietic cells (arrow). All the cells in the cluster were positive, but this cannot be appreciated in a single focal plane. (E) and (F) LacZ staining in E11.5 fetal liver of a wt (E) and heterozygous SCLlacZ/w embryo (F) showing specific staining in large megakaryocytes and smaller erythroblasts. Original magnification: (A, C through F), ×400; (B), ×1,000.

β Galactosidase expression inSCLlacZ/w embryos shows the hematopoietic, vascular, and neural expression patterns of SCL.

The major sites of lacZ expression in mid- and later-gestationSCLlacZ/w embryos were the hematopoietic compartment and the developing nervous system, consistent with the sites of SCL mRNA and protein expression detected in previous studies.9,28,33 In the central nervous system, weak β galactosidase expression was first observed at E10.5 ventrally in the presumptive spinal cord (Fig 5A and B), in a similar distribution to that described for SCL in the frog34 and the zebrafish.35 At E12.5, expression in the midbrain was evident laterally in the tegmentum and in the fiber tracts of the posterior commissure and proceeded to encompass most of the tectum and the tegmentum by E13.5 (Fig 5C through F). Later in embryogenesis, expres-sion of β galactosidase was strongest in the superior tectum, in the region that would ultimately become the superior colliculi and weaker expression persisted in the inferior tectum, the site of the definitive inferior colliculi (compare E18.5 and adult panels in Fig 5G and I). LacZ expression was also apparent in fiber tracts on the ventral surface of the brainstem in embryonic and adult brains and in cortical radiations and descending tracts from the tectum in adult brains (Fig 5H and J and data not shown).

Most primitive, yolk sac–derived erythoid cells in E9.5SCLlacZ/w embryos expressed β galactosidase, although the level of expression varied from cell to cell (Fig 6A). However, by E12.5, lacZ expression was no longer apparent in the nucleated, primitive erythrocytes, although some of the earliest circulating definitive erythocytes transiently retained β galactosidase activity (Fig 6B).

Between E10.5 and E11.5, there is a switch from primitive hematopoiesis in the yolk sac to definitive hematopoiesis in the fetal liver. This transition is associated with a brief period of definitive hematopoietic activity in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region of the embryo, a derivative of the paraaortic splanchnopleura.36It is hypothesized that these hematopoietic progenitor cells form intravascular clusters comprising 4 to 15 cells attached to the wall of the aorta and some of its branches.37 As anticipated, endothelial expression of β galactosidase was seen inSCLlacZ/w embryos, although expression was quite weak (Fig 6C). In addition, however, there were small aggregates of lacZ-positive cells along the ventrolateral aortic wall of E10.5 to E11.5 embryos (Fig 6D). Isolation of these SCL-expressing cells will be required to determine whether they represent the definitive hematopoietic precursors in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region. Strong β galactosidase activity in SCLlacZ/w embryos was apparent in the fetal liver, the dominant hematopoietic organ from E11.5 until birth. On histological section, there was intense lacZ staining of megakaryocytes and weaker expression in erythoid cells (Fig6E and F).

From E10.5, embryos were large enough to allow a more accurate quantification of lacZ expression in circulating blood cells through FACS-Gal analysis. As shown in Fig 7A, yolk sac–derived blood cells from E10.5 SCLlacZ/wembryos showed elevated β galactosidase activity compared withSCLw/w embryonic blood. As the circulating primitive erythroid populations became morphologically more mature, the level of β galactosidase activity fell (compare the profiles from E12.5 with E10.5 to E11.5 in Fig 7A). The subpopulations of lacZ-positive cells seen in E12.5 and E13.5 blood were shown by histochemical staining to be enucleated erythrocytes (eg, Fig 6B).

Representative FACS profiles showing β galactosidase activity in (A) E10.5 to E13.5 embryonic blood cells and (B) E11.5 to E18.5 fetal liver cells from SCLlacZ/w (solid line) and SCLw/w (dashed line) embryos. (A) β galactosidase activity in SCLlacZ/w yolk sac–derived erythroid cells decreased after E11.5. The major peaks represent fluorescence derived from primitive erythroid cells and the minor peaks of high β galactosidase activity seen in the E12.5 and E13.5 samples were in the initial wave of definitive, enucleated erythrocytes (see Fig 6). Results are representative of analyses performed on 2 litters of embryos for each time point. (B) In theSCLlacZ/w fetal livers, the percentage (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) of cells expressing high levels of β galactosidase activity at each developmental time point are shown. Results are representative of analyses performed on 1 to 3 litters of embryos for each time point.

Representative FACS profiles showing β galactosidase activity in (A) E10.5 to E13.5 embryonic blood cells and (B) E11.5 to E18.5 fetal liver cells from SCLlacZ/w (solid line) and SCLw/w (dashed line) embryos. (A) β galactosidase activity in SCLlacZ/w yolk sac–derived erythroid cells decreased after E11.5. The major peaks represent fluorescence derived from primitive erythroid cells and the minor peaks of high β galactosidase activity seen in the E12.5 and E13.5 samples were in the initial wave of definitive, enucleated erythrocytes (see Fig 6). Results are representative of analyses performed on 2 litters of embryos for each time point. (B) In theSCLlacZ/w fetal livers, the percentage (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) of cells expressing high levels of β galactosidase activity at each developmental time point are shown. Results are representative of analyses performed on 1 to 3 litters of embryos for each time point.

The level of β galactosidase activity inSCLlacZ/w fetal liver cells from E11.5 to E18.5 was determined using the FACS-Gal technique. At E11.5, subsets of fetal liver hematopoietic cells expressing high and low levels of β galactosidase were discernible (Fig 7B). Over time, there was a progressive decrease in the percentage of lacZ-positive cells. This was most readily appreciated as a decrease in the percentage of lacZhigh cells, from approximately 55% of the fetal liver at E11.5 to approximately 10% at E18.5.

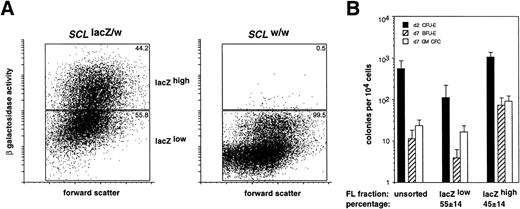

We have previously demonstrated that SCL was expressed in hematopoietic progenitor cells in the adult mouse.22Therefore, we determined whether the level of SCL expression in the fetal liver, inferred by the measurement of β galactosidase activity, could also be used as a criterion to enrich for hematopoietic progenitor cells. The distribution of erythroid and myeloid CFCs in the lacZhigh and lacZlow fractions from E12.5SCLlacZ/w fetal livers was determined. This stage of development represented the earliest time point at which sufficient numbers of fetal liver cells could be harvested for analysis from individual embryos. As seen in Fig 8A, ≈45% of SCLlacZ/w and ≈0.5% ofSCLw/w in E12.5 fetal liver cells were lacZhigh. Culture of lacZhigh and lacZlow fetal liver cells demonstrated significant enrichment for erythroid and myeloid CFCs in the lacZhighcompared with the lacZlow fraction (Fig 8B). The enrichment for erythroid CFCs (10-fold for CFU-E and 20-fold for BFU-E) was greater than for myeloid CFCs (5-fold) suggesting higher levels ofSCL expression in erythroid rather than myeloid progenitors. Most CFCs were in the lacZhigh fetal liver fraction, consistent with our previous findings in the adult bone marrow (Table 1).

Enrichment for myeloid and erythroid CFCs in the lacZhigh fraction of fetal livers fromSCLlacZ/w mice. (A) Representative FACS profiles of forward scatter plotted against β galactosidase activity (measured as fluorescence) for FACS-Gal–labeled E12.5 fetal liver cells fromSCLlacZ/w and SCLw/w embryos. Sort windows and the percentage of cells in each window are shown for lacZlow and lacZhigh fractions for each genotype. (B) Frequency of d2 CFU-E and d7 BFU-E and myeloid (GM) CFC in cultures of unsorted and sorted fetal liver fractions fromSCLlacZ/w mice cultured in Epo (for d2 CFU-E) or IL-3/Epo (for d7 BFU-E and GM-CFC). Values represent the mean ± SD from replicate cultures of 10 fetal livers from 3 litters of embryos. The percentage of fetal liver cells, which were sorted into each fraction, is indicated.

Enrichment for myeloid and erythroid CFCs in the lacZhigh fraction of fetal livers fromSCLlacZ/w mice. (A) Representative FACS profiles of forward scatter plotted against β galactosidase activity (measured as fluorescence) for FACS-Gal–labeled E12.5 fetal liver cells fromSCLlacZ/w and SCLw/w embryos. Sort windows and the percentage of cells in each window are shown for lacZlow and lacZhigh fractions for each genotype. (B) Frequency of d2 CFU-E and d7 BFU-E and myeloid (GM) CFC in cultures of unsorted and sorted fetal liver fractions fromSCLlacZ/w mice cultured in Epo (for d2 CFU-E) or IL-3/Epo (for d7 BFU-E and GM-CFC). Values represent the mean ± SD from replicate cultures of 10 fetal livers from 3 litters of embryos. The percentage of fetal liver cells, which were sorted into each fraction, is indicated.

Distribution of Clonogenic Cells in SortedSCLlacZ/w E12.5 Fetal Liver Fractions

| Stimulus* . | Colony Type . | Progenitor Yield† . | Colony Distribution (%)‡ . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsorted . | Sorted . | lacZlow . | lacZhigh . | ||

| Epo | d2 CFU-E | 547 ± 310 | 519 ± 234 | 9 ± 5 | 91 ± 5 |

| Epo/IL 3 | d7 BFU-E | 11 ± 7 | 28 ± 10 | 9 ± 7 | 91 ± 7 |

| d7 myeloid | 23 ± 9 | 46 ± 17 | 20 ± 6 | 80 ± 6 | |

| Stimulus* . | Colony Type . | Progenitor Yield† . | Colony Distribution (%)‡ . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsorted . | Sorted . | lacZlow . | lacZhigh . | ||

| Epo | d2 CFU-E | 547 ± 310 | 519 ± 234 | 9 ± 5 | 91 ± 5 |

| Epo/IL 3 | d7 BFU-E | 11 ± 7 | 28 ± 10 | 9 ± 7 | 91 ± 7 |

| d7 myeloid | 23 ± 9 | 46 ± 17 | 20 ± 6 | 80 ± 6 | |

Sorted and unsorted fetal liver cells from 10SCLlacZ/w E12.5 embryos from 3 litters were cultured in duplicate in methylcellulose in the presence of growth factors for 2 or 7 days and the colonies counted. Epo was used at 4 U/mL and IL-3 at 1,000 U/mL.

The number of CFCs in cultures of 1 × 104 unsorted fetal liver cells compared with the calculated yield of CFCs from the sorted fractions. The progenitor cell yield was estimated by summing the number of progenitor cells recovered in the lacZhighand lacZlow fractions for each colony type. The number of progenitor cells was derived by multiplying the progenitor frequency by the % cells in each fraction. Mean values for progenitor cell frequency and the percentage of cells in each fraction are shown in Fig8B. Values given represent the mean ± SD of 10 fetal livers.

The distribution of CFCs between the sorted fetal liver fractions given as a percentage.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have used the SCL-lacZ “knock-in” mice to accurately delineate SCL-expressing regions in the brain, hematopoietic tissues, and vasculature throughout embryogenesis. Linking β galactosidase expression to transcription from theSCL promoter allowed us to use lacZ staining to map the distribution of cells fated to express SCL in both heterozygous (SCLlacZ/w) and SCL-null (SCLlacZ/lacZ) embryos. This has enabled us to explore in detail the previously identified vascular abnormalities seen in SCL-null embryos.2,31 A comparison of lacZ staining in SCLlacZ/w mice with the SCLexpression patterns determined in prior studies validated β galactosidase expression as a facsimile for SCL expression and extended the previous findings.9,28,29,33,38 The expression analysis of SCL homologues in Xenopus laevis andDanio rerio has shown that SCL is expressed in the mesodermal precursors of blood and endothelial cells in these species also,34,35,39 40 suggestive of a conserved role forSCL in blood formation throughout vertebrate evolution.

LacZ expression in embryonic blood and fetal liver provided additional insights into the pattern of SCL expression in developing hematopoietic cells. Because SCL expression decreases as erythroblasts mature,11,12,14 the synchronous fall in β galactosidase activity in SCLlacZ/w circulating primitive erythroblasts after E11.5 was consistent with the hypothesis that primitive erythropoiesis occurs as a single “wave.”41,42 Similarly, the progressive decline in β galactosidase activity in the developing fetal liver may have reflected its increasing complement of more mature hematopoietic cells in addition to its decreasing progenitor content.26Consistent with this, there was a strong correlation between progenitor cell frequency and lacZ expression in the fetal liver, as previously reported for experiments using adult bone marrow cells.22

A number of studies have documented the presence of definitive hematopoietic progenitors in the paraaortic splanchnopleura or its derivative, the aorta-gonad-mesonephros, in the embryo before the development of fetal liver hematopoiesis.36 It is likely that the hematopoietic precursor activity resides in clusters of cells associated with the ventral wall of the aorta and the umbilical artery. Cells forming these clusters, which have been observed in the mouse,37,43 human,44-46 and chick,47 express a coterie of genes associated with hematopoietic progenitors.36,43,46,48-50 Our data indicates that murine aortic clusters express SCL. This result complements a recent in situ hybridization study in human embryos in which these aorta-associated cells were shown to expressSCL.46

The pattern of β galactosidase expression in the ventral spinal cord and the developing midbrain of SCLlacZ/w mice mirrored the results of earlier studies in mouse embryos9,28,33 and bore great similarity to the pattern and kinetics of SCL expression in the central nervous system of amphibians and teleost fish. 34,35,40 We extended these studies to late embryonic and postnatal life, demonstrating that the lacZ-positive sites in the mouse embryonic midbrain developed into the superior and inferior colliculi, laminated cortical structures concerned with reflex movements of the eyes and head in response to visual and auditory stimuli.51,52 It is interesting that members of several protein classes known to interact with SCL, notably the GATA proteins,53-56 have overlapping patterns of expression in the central nervous system. However, delineation of the precise role played by SCL in neural development awaits the generation of mutant animals in which SCL is specifically deleted in these cells.

At a gross morphological level, SCL-null embryos developed normally until the early somite stage,2,3 when circulation between the yolk sac and the embryo is established. However, in the absence of hematopoietic cells, SCL-null embryos died at ≈E9.5.2,3 Therefore, there existed only a narrow window in which the SCLlacZ/lacZ embryos could be evaluated for developmental defects free from any confounding effects of hypoxic cell death. The pattern of lacZ staining at E7.5 indicated that SCL was not required for the migration of mesoderm into the yolk sac. The yolk sac endothelial cells in precirculationSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos may have represented the limited differentiation potential of SCL-null yolk sac hemangioblasts. The failure of these endothelia to form more than rudimentary capillary networks provided evidence for a cell-autonomous requirement for SCL in yolk sac vascular development as recently suggested by Visvader et al.31

In contrast to the minimal development present in the yolk sac, vascular development in precirculation SCLlacZ/lacZembryos was more extensive. The pattern of lacZ staining in endocardium and in the dorsal aorta, allantoic, and cerebral vascular plexuses matched the vascular expression of PECAM-1 seen in both wild-type andSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos at this stage. These data implied that the specification of embryonic angioblasts and their appropriate differentiation and migration within the embryo to form vessels were not dependent on the SCL protein.

The vascular abnormalities we have described in this study are similar to those seen in a number of mouse strains in which genes have been disrupted by gene targeting. Embryos null for transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 or its receptor, TGF-β RII, formed yolk sacs with an abnormal primary vascular plexus and reduced hematopoiesis, which closely mimicked the phenotype of SCL-null embryos.57,58 As was the case in SCL-knockout embryos, early embryonic vasculature developed normally. Yolk sac endothelium was completely absent from embryos lacking the transcription factor myocyte enhancer factor (MEF)-2C and, in this instance, embryonic vasculogenesis was also severely perturbed, although hematopoietic cells were present in the yolk sac.59 It was interesting thatSCLlacZ/lacZ embryos displayed a milder vascular defect, but more severe hematopoietic abnormality thanMEF2C−/− embryos. In embryos lackingFLK-1 (VEGF-R2) or its major ligand, VEGF, specification of endothelial precursors occurred, but organized blood vessels were absent and hematopoiesis was markedly impaired.49,50,60-62 Abnormalities in yolk sac vascular maturation or remodeling were also prominent in embryos deficient in the heterodimeric bHLH-PAS transcription factor, hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1,63-65 the endothelial TIE2receptor,66,67 and its ligand, Ang-1,68the ETS-family transcription factor, TEL,69 and the major VEGF receptor expressed on lymphatics, VEGF-R3.70Similarly, embryos deficient in ephrinB2 or in bothEphB2 and EphB3 receptors displayed lethal defects in remodeling of yolk sac and cerebral primary vascular plexuses.71 72 Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis on SCL-null embryos showed intact expression of ephrinB2, and its ligand EphB4 (data not shown).

A striking feature of the SCLlacZ/lacZ embryos (and many of the other knock-out mice described above) was the greater severity of the vascular defect in the yolk sac than in the embryo. This suggests that endothelial precursors in different sites in the mouse embryo may differ in their requirements for certain growth factors or transcription factors, including SCL. This may be analogous to the situation in the chick, in which two populations of angioblasts, one with and one without hematopoietic potential, have been described.73 74 However, the precise molecular pathways, which regulate vascular and hematopoietic specification and the way in which SCL participates in this process, remains to be elucidated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Frank Battye for assistance with cell sorting and Dr Thomas Sato for providing the anti–PECAM-1 staining method. Koula Kosmopoulos, Rachel Mansfield, Viki Lapatis, Dora Kaminaris, and Jenny Parker provided expert technical assistance. We thank the staff of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute animal facility for the care of our mice and Simon Olding for the production of figures.

Supported by the Lions Special Fellowship (A.G.E.) and the Fraser Fellowship (C.G.B.) of the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria, the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Charitable Foundation (L.R.), the National Health and Medical Research Council (Canberra), the Australian Federal Government Cooperative Research Centres Program, and the Bone Marrow Donor Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Andrew G. Elefanty, FRACP PhD, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, PO Royal Melbourne Hospital, Victoria 3050, Australia; e-mail:elefanty@wehi.edu.au.

![Fig. 7. Representative FACS profiles showing β galactosidase activity in (A) E10.5 to E13.5 embryonic blood cells and (B) E11.5 to E18.5 fetal liver cells from SCLlacZ/w (solid line) and SCLw/w (dashed line) embryos. (A) β galactosidase activity in SCLlacZ/w yolk sac–derived erythroid cells decreased after E11.5. The major peaks represent fluorescence derived from primitive erythroid cells and the minor peaks of high β galactosidase activity seen in the E12.5 and E13.5 samples were in the initial wave of definitive, enucleated erythrocytes (see Fig 6). Results are representative of analyses performed on 2 litters of embryos for each time point. (B) In theSCLlacZ/w fetal livers, the percentage (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) of cells expressing high levels of β galactosidase activity at each developmental time point are shown. Results are representative of analyses performed on 1 to 3 litters of embryos for each time point.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/11/10.1182_blood.v94.11.3754/4/m_blod42305007x.jpeg?Expires=1767839125&Signature=3NKHEARhTb73b3az0YDuL3Z-ayYF8d1q1iC0iwJLER34P3hWr0jT6~MNti0kb0ByZEs3U7W0oPT1j3smfWC2mtlBQa5E71d7k3fJOI0zYbA~cOLJVFLracb~GSVuE19So5GYR3vWO5x-gL5n22RsLdAdyRGYF6FgwJXdusOpq-CVe8OjtDhCGROpq01MwGSNzRSoYZ~~p48lkpAXCe-ti4WPXCZccwOspnlMFVCxuzkCDFUeFEH~~oKSavUBK8D01oNMfbkVA6HpqOnutFuDGUGh7VEUWNVGoiuxrbBltrDHaIp00jHw1QgLO-0sb6seWRXBKbQuyBl74CmFeFUlIA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal