Abstract

Survivin is an inhibitor of apoptosis overexpressed in various human cancers but undetectable in normal differentiated tissues. A potential expression and prognostic significance of survivin was studied in 222 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (centroblastic, 96%; immunoblastic, 4%). All patients were enrolled between 1987 and 1993 (median follow-up, 7 years) in the LNH87 protocol of the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA) and treated either with the reference ACVBP arm (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone)[AU3A] (n = 79) or other experimental anthracycline-containing regimens (n = 143). The characteristics of these patients were median age of 56 years; serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) greater than 1N, 60%; stage III-IV, 55%; performance status, according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale, more than 1, 23%; extranodal sites more than 1, 29%; mass more than 10 cm, 44%; bone marrow involvement, 15%. Of the 222 patients studied, 134 (60%) revealed survivin expression in virtually all tumor cells by immunohistochemistry. The overall 5-year survival rate was significantly lower in patients with survivin expression than in those without (40% vs 54%, P = .02). Multivariate analysis incorporating prognostic factors from the International Prognostic Index (IPI) identified survivin expression as an independent predictive parameter on survival (P = .03, relative risk [RR] = 1.6) in addition to LDH (P = .02, RR = 1.6), stage (P = .03, RR = 1.7), and ECOG scale (P = .05, RR = 1.6). A second analysis incorporating IPI as a unique parameter demonstrated that survivin expression (P = .02, RR = 1.6) remained a prognostic factor for survival independently of IPI (P = .001, RR = 1.5). Survivin expression may be considered a new unfavorable prognostic factor of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas represent the most frequent type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL)—30% to 40% of adult NHL1—diagnosed on morphology and immunophenotype.2,3 Although combination chemotherapy has improved the outcome, many patients do not achieve complete remission (CR) and they ultimately relapse, making the search for parameters identifying patients at high risk of recurrent disease particularly urgent.4 The formulation of an International Prognostic Index (IPI) has provided a widely accepted set of criteria to predict the evolution of aggressive lymphomas5 and thus to design appropriate therapies. IPI takes into account factors that are mostly linked to the patient's characteristics or to the disease's extension and growth, including age, lactate dehydrogenase level, performance status, clinical stage, and number of extranodal sites. However, one limitation of this prediction strategy is that IPI does not encompass molecular abnormalities of tumor cells, which may play a critical role in determining profoundly different clinical outcomes in patients within the same group defined by IPI.6

Molecular abnormalities of the cell death–cell viability balance as reflected in bcl-2 overexpression7-10 or p53 mutation11,12 have emerged as important prognostic indicators of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. A candidate molecule to influence the apoptotic balance in cancer was recently identified as survivin,13 a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) gene family.14 Unique among other IAP proteins, survivin is expressed during embryonic and fetal development,15becomes undetectable in normal adult tissues, and is prominently overexpressed in a variety of human cancers in vivo.13Accordingly, a recent analysis of 3.5 million human “transcriptomes” identified survivin among the top 4 transcripts uniformly up-regulated in cancer but not in normal tissues.16 At a molecular level, survivin is expressed during mitosis in a strict cell cycle–dependent manner, and it localizes to mitotic spindle microtubules in a reaction required for apoptosis inhibition.17 This pathway may provide a selective cytoprotective mechanism at cell division, because targeting endogenous survivin with antisense or a dominant negative mutant caused spontaneous apoptosis and a profound dysregulation of mitotic progression with supernumerary centrosomes, multipolar mitotic spindles, and generation of multinucleated cells.18Although retrospective predictive or prognostic studies on the impact of the survivin pathway in selected solid tumors have been reported,19-23 little is known about the potential role of this molecule in hematopoietic malignancies. In this study, we sought to investigate the potential expression of survivin in 222 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma enrolled in the prospective LNH87 protocol of the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA) and to dissect its potential prognostic value for disease progression and clinical outcome.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

The NHL series of the present study included patients registered in the LNH87 trial with a diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma confirmed by pathologic review. The LNH87 trial, conducted by GELA, recruited patients from 50 participating French and Belgian centers who were at least 15 years old and had intermediate- or high-grade NHL, according to the Working Formulation. Disease dissemination was evaluated before treatment by physical examination, bone marrow (BM) biopsy, and computed tomography scan of the chest and abdomen. Patients were staged according to the Ann Arbor system. The number of extranodal sites and larger tumor mass diameter were also determined. Performance status was assessed according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale, in which 0 indicated that the patient had no symptoms; 1, the patient had symptoms but was ambulatory; 2, the patient was bedridden less than half the day; 3, the patient was bedridden half the day or longer; and 4, the patient was chronically bedridden and required assistance with activities of daily living. Performance status was classified as 0 or 1 (the patient was ambulatory) or 2, 3, 4 (the patient was not ambulatory). The lactate dehydrogenase level was expressed as the ratio over the maximal normal value. From October 1, 1987, to April 1, 1993, 3232 patients had been included in the LNH87 trial. At the time of the analysis, 88% of the slides were available for pathologic review and 1404 patients were considered to have diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (centroblastic and immunoblastic).

Treatment and assessment of response

Patients were stratified into 4 groups according to age and the presence of the following adverse prognostic factors: performance status greater than 1; 2 or more extranodal sites; tumor diameter 10 cm or larger; and BM or central nervous system involvement. Details of the chemotherapy regimens have been reported elsewhere.24,25 Group 1 included patients younger than age 70 without any adverse prognostic factors. Patients were randomly assigned to receive 8 cycles of mBACOD (Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, bleomycin, methotrexate, Decadron) or 3 courses of ACVB (Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, prednisone) followed by the consolidation treatment according to the LNH84 protocol.26Group 2 included patients 15 to 54 years old with at least one adverse prognostic factor. Patients were randomly assigned to receive 4 inductive cycles of ACVB or NCVB (same as ACVB but with mitoxantrone instead of Adriamycin) and, if they reached CR, were randomized between consolidation with autologous BM transplantation or sequential chemotherapy as per the LNH84 protocol.25 Group 3 included patients 55 to 70 years old with at least one adverse prognostic factor. Patients were randomized to receive 4 cycles of ACVB followed by the consolidation of the LNH84 protocol or 4 alternating induction cycles every 3 weeks of VIM3 (mitoxantrone, ifosfamide, methyl-GAG, Vehem, prednisone, methotrexate) and ACVB and then a maintenance therapy with alternative cycles of VIM (mitoxantrone, vepesid, ifosfamide) and ACVM (Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, methotrexate).27 Group 4 included patients over 70 years old. They were randomly assigned to receive CVP (cyclophosphamide, Vehem, prednisone) or CTVP (CVP plus tetrahydropyranyladriamycin) for 6 cycles.28 Response to therapy was evaluated after induction treatment. CR was defined as the disappearance of all clinical evidence of disease and the normalization of all laboratory values, radiographs, computed tomography scans, and BM.

Histologic and immunophenotypic study

The histologic diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of patients enrolled in the LNH87 protocol was made independently by 3 pathologists according to the updated Kiel classification,29 and to the morphologic variants in the new proposed WHO classification,3 as centroblastic, immunoblastic, or anaplastic large cell. The anaplastic variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas was excluded from this study. The diagnosis was based on morphologic examination of slides from routinely paraffin-embedded samples stained with hematoxylin-eosin, Giemsa, and Gordon-Sweet stains and on immunophenotyping results. In all cases, immunophenotyping was performed by panel review with antibodies including CD20/L26, for the B-cell lineage and CD3 and CD45RO for the T-cell lineage (UCHL1) (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) to determine the B- or T-cell lineage, respectively, using an indirect immunoperoxidase or alkaline phosphatase antialkaline phosphatase method.

Patient selection for survivin expression

Survivin expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas was analyzed on the basis of availability of 3 unstained slides per case. Cases fixed in Bouin's liquid were excluded, and only formalin-fixed cases were selected. To avoid bias related to treatment, only patients who received an anthracycline-containing regimen were included in the study. Therefore, patients enrolled in group 4 treated by CVP were excluded. Overall, 222 cases were studied for survivin expression by immunohistochemistry. Tissue sections measuring 5 μm were put on high adhesive slides, boiled for 5 minutes in a standard pressure cooker for antigen retrieval, blocked in 10% normal goat serum, and incubated for 14 hours at 4°C with affinity-purified antisurvivin polyclonal rabbit antibody—used and characterized previously.13 After washes, the slides were incubated with biotin-conjugated goat antirabbit immunoglobulin G (Vector, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes at 22°C. Binding of the primary antibody was revealed by addition of streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) and 3′3′-diaminobenzidine followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin. In control experiments, slides were incubated with comparable concentrations of nonimmune rabbit serum. Cases were scored as positive (70%-90% of cells exhibiting intracytoplasmic staining) or negative (fewer than 5% of stained cells). The immunohistochemical study was performed twice per case and interpreted without any knowledge of the clinical data.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics and CR rates were compared using the chi-square test. Overall survival time was calculated from the date of randomization until death or last follow-up examination. Survival curves were estimated using the product-limit method of Kaplan-Meier30 and were compared using the log-rank test. Univariate analyses were made using the chi-square test and the log-rank test. A multivariate regression analysis according to the Cox proportional hazards regression model,31 with the overall survival as the dependent variable, was used to adjust the effect of survivin expression for potential independent prognostic factors.P < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All calculations were performed on an SAS software, version 6.10 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

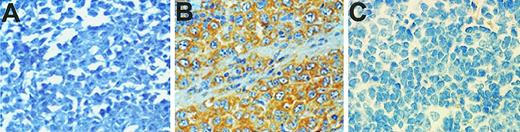

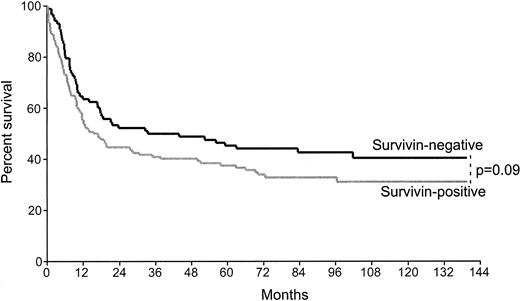

Survivin expression was demonstrated in 60% of the patients examined by immunohistochemistry (134 of 222) (Figure1). The median age of the population was 56 years. The main clinical characteristics and treatment regimens of this group were similar to those of the remaining group of 1182 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphomas involved in the LNH87 trial (Table 1). The clinical characteristics and allocated treatment regimens were well balanced between the survivin-positive and survivin-negative groups analyzed (Table 2). The CR rate of survivin-positive cases (61%) did not significantly differ from that of the survivin-negative population (68%, P = .29). The event-free survival was lower in survivin-positive patients than the survivin-negative group, but it did not reach statistical significance (P = .09) (Figure 2). Of note, there was also a more pronounced decreased survival after relapse in the survivin-positive group as compared with the survivin-positive patients (P = .08).

Expression of survivin in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas by immunohistochemistry.

Sections measuring 5 μm from paraffin-embedded tissues were cut on high adhesive slides, boiled for 5 minutes for antigen retrieval, blocked in 10% normal goat serum, and incubated with an antibody to survivin followed by biotin-conjugated goat antirabbit immunoglobulin G and streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase. Binding of the primary antibody was revealed by addition of 3′3′-diaminobenzidine followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin. (A) Representative case of large B-cell lymphoma negative for survivin expression. (B) Representative case positive for survivin expression. (C) Representative control staining of a survivin-positive case with nonimmune rabbit antibody.

Expression of survivin in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas by immunohistochemistry.

Sections measuring 5 μm from paraffin-embedded tissues were cut on high adhesive slides, boiled for 5 minutes for antigen retrieval, blocked in 10% normal goat serum, and incubated with an antibody to survivin followed by biotin-conjugated goat antirabbit immunoglobulin G and streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase. Binding of the primary antibody was revealed by addition of 3′3′-diaminobenzidine followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin. (A) Representative case of large B-cell lymphoma negative for survivin expression. (B) Representative case positive for survivin expression. (C) Representative control staining of a survivin-positive case with nonimmune rabbit antibody.

Clinical characteristics of the survivin group and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas patients enrolled in the LNH87 protocol

| Characteristic . | Survivin group (n = 222) . | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n = 1182) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y | 56 | 57 | |

| Clinical stage III, IV, % | 55 | 57 | .51 |

| Bulky disease > 10 cm, % | 44 | 51 | .07 |

| Bone marrow involvement, % | 15 | 17 | .59 |

| Entranodal sites > 1, % | 29 | 30 | .78 |

| ECOG PS > 1, % | 23 | 26 | .50 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase > 1N, % | 60 | 57 | .39 |

| IPI score, % | .87 | ||

| Low (0-1) | 41 | 39 | |

| Low intermediate (2) | 21 | 23 | |

| High intermediate (3) | 21 | 20 | |

| High (4-5) | 17 | 18 | |

| Evolution, % | .77 | ||

| Complete remission | 64 | 65 |

| Characteristic . | Survivin group (n = 222) . | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n = 1182) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y | 56 | 57 | |

| Clinical stage III, IV, % | 55 | 57 | .51 |

| Bulky disease > 10 cm, % | 44 | 51 | .07 |

| Bone marrow involvement, % | 15 | 17 | .59 |

| Entranodal sites > 1, % | 29 | 30 | .78 |

| ECOG PS > 1, % | 23 | 26 | .50 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase > 1N, % | 60 | 57 | .39 |

| IPI score, % | .87 | ||

| Low (0-1) | 41 | 39 | |

| Low intermediate (2) | 21 | 23 | |

| High intermediate (3) | 21 | 20 | |

| High (4-5) | 17 | 18 | |

| Evolution, % | .77 | ||

| Complete remission | 64 | 65 |

ECOG PS indicates performance status according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale.

Clinical characteristics of the 222 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma according to survivin expression

| Characteristic . | Survivin negative . | Survivin positive . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients (%) | 88 (40) | 134 (60) | |

| Age (%) | .56 | ||

| No older than 60 y | 56 (64) | 80 (60) | |

| Older than 60 y | 32 (36) | 54 (40) | |

| Histologic subtype (%) | .10 | ||

| Centroblastic | 81 (92) | 130 (97) | |

| Immunoblastic | 7 (8) | 4 (3) | |

| Clinical stage (%) | .12 | ||

| I or II | 45 (52) | 54 (41) | |

| III or IV | 42 (48) | 78 (59) | |

| Bulky disease > 10 cm (%) | .31 | ||

| No | 43 (52) | 76 (59) | |

| Yes | 40 (48) | 53 (41) | |

| Bone marrow involvement (%) | .11 | ||

| No | 71 (90) | 103 (82) | |

| Yes | 8 (10) | 23 (18) | |

| Extranodal sites (%) | .91 | ||

| 0-1 site | 63 (72) | 95 (71) | |

| More than 1 site | 25 (28) | 39 (29) | |

| Performance status (%) | .07 | ||

| 0-1 | 69 (83) | 95 (73) | |

| More than 1 | 14 (17) | 36 (27) | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (%) | 0.99 | ||

| Normal | 33 (40) | 48 (40) | |

| Elevated | 50 (60) | 73 (60) | |

| IPI Score (%) | 0.48 | ||

| 0-1 | 37 (46) | 45 (38) | |

| 2 | 17 (21) | 26 (22) | |

| 3 | 17 (21) | 24 (20) | |

| 4-5 | 10 (12) | 24 (20) | |

| Treatment (%) | 0.72 | ||

| ACVB | 30 (34) | 49 (36) | |

| m-BACOD (group 1) | 18 (21) | 20 (15) | |

| NCVB (group 2) | 16 (18) | 20 (15) | |

| VIM3 (group 3) | 15 (17) | 29 (22) | |

| CTVP (group 4) | 9 (11) | 16 (12) | |

| Evolution (%) | 0.29 | ||

| Complete remission | 57 (68) | 74 (61) | |

| No complete remission | 27 (32) | 48 (39) |

| Characteristic . | Survivin negative . | Survivin positive . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients (%) | 88 (40) | 134 (60) | |

| Age (%) | .56 | ||

| No older than 60 y | 56 (64) | 80 (60) | |

| Older than 60 y | 32 (36) | 54 (40) | |

| Histologic subtype (%) | .10 | ||

| Centroblastic | 81 (92) | 130 (97) | |

| Immunoblastic | 7 (8) | 4 (3) | |

| Clinical stage (%) | .12 | ||

| I or II | 45 (52) | 54 (41) | |

| III or IV | 42 (48) | 78 (59) | |

| Bulky disease > 10 cm (%) | .31 | ||

| No | 43 (52) | 76 (59) | |

| Yes | 40 (48) | 53 (41) | |

| Bone marrow involvement (%) | .11 | ||

| No | 71 (90) | 103 (82) | |

| Yes | 8 (10) | 23 (18) | |

| Extranodal sites (%) | .91 | ||

| 0-1 site | 63 (72) | 95 (71) | |

| More than 1 site | 25 (28) | 39 (29) | |

| Performance status (%) | .07 | ||

| 0-1 | 69 (83) | 95 (73) | |

| More than 1 | 14 (17) | 36 (27) | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (%) | 0.99 | ||

| Normal | 33 (40) | 48 (40) | |

| Elevated | 50 (60) | 73 (60) | |

| IPI Score (%) | 0.48 | ||

| 0-1 | 37 (46) | 45 (38) | |

| 2 | 17 (21) | 26 (22) | |

| 3 | 17 (21) | 24 (20) | |

| 4-5 | 10 (12) | 24 (20) | |

| Treatment (%) | 0.72 | ||

| ACVB | 30 (34) | 49 (36) | |

| m-BACOD (group 1) | 18 (21) | 20 (15) | |

| NCVB (group 2) | 16 (18) | 20 (15) | |

| VIM3 (group 3) | 15 (17) | 29 (22) | |

| CTVP (group 4) | 9 (11) | 16 (12) | |

| Evolution (%) | 0.29 | ||

| Complete remission | 57 (68) | 74 (61) | |

| No complete remission | 27 (32) | 48 (39) |

Kaplan-Meier curves of event-free survival of 222 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma according to survivin expression.

Survivin-negative cases, n = 88; survivin-positive cases, n = 134.

Kaplan-Meier curves of event-free survival of 222 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma according to survivin expression.

Survivin-negative cases, n = 88; survivin-positive cases, n = 134.

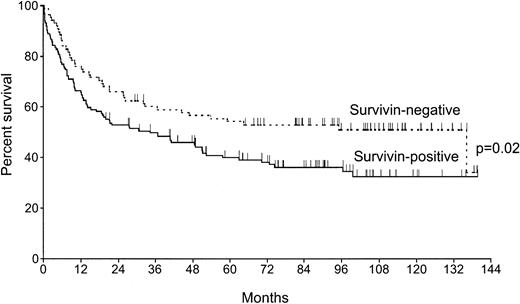

With a median follow-up of the surviving patients of 91 months (range, 20-140 months), the 5-year overall survival rate was significantly lower in patients expressing survivin as compared with the survivin-negative group: 40% (CI 32-48) versus 54% (CI 44-64),P = .02 (Figure 3). The estimated relative risk (RR) of death for patients with survivin expression was 1.6, which was similar to that of other well-known prognostic factors (Table 3). After incorporating IPI as a unique parameter in a second multivariate analysis, survivin expression remained a prognostic factor (P = .02, RR = 1.6) independently of IPI (P = 0.001, RR = 1.5).

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival of 222 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma according to survivin expression.

Survivin-negative cases, n = 88; survivin-positive cases, n = 134.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival of 222 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma according to survivin expression.

Survivin-negative cases, n = 88; survivin-positive cases, n = 134.

Cox regression analysis for overall survival with factors identified by the International Prognostic Index

| Factor . | P . | Risk ratio label (95% confidence interval) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | .27 | 1.2 (0.8-1.8) |

| Extranodal sites | .63 | 1.1 (0.7-1.8) |

| Performance status | .05 | 1.6 (1.0-2.4) |

| Clinical stage | .03 | 1.7 (1.1-2.7) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | .02 | 1.6 (1.1-2.5) |

| Survivin | .03 | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) |

| Factor . | P . | Risk ratio label (95% confidence interval) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | .27 | 1.2 (0.8-1.8) |

| Extranodal sites | .63 | 1.1 (0.7-1.8) |

| Performance status | .05 | 1.6 (1.0-2.4) |

| Clinical stage | .03 | 1.7 (1.1-2.7) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | .02 | 1.6 (1.1-2.5) |

| Survivin | .03 | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) |

Discussion

In this series of 222 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphomas treated with an anthracycline-containing regimen, we found that survivin expression predicted a shorter overall survival. This selected series is representative of the whole population of aggressive non-Hodgkin's B-cell lymphomas enrolled in the LNH87 trial as shown by the similar repartition of main clinical characteristics. The classical prognostic parameters in aggressive B-cell lymphomas (advanced clinical stage, unfavorable performance status, elevated lactate dehydrogenase values) and, consequently, IPI score were significantly associated with a poor outcome in this series of 222 patients. Importantly, multivariate analyses demonstrated that the influence of survivin expression on overall survival was independent of these well-established prognostic factors. Although not reaching statistical significance, survivin-positive patients exhibited shorter event-free survival and relapse-free survival than the survivin-negative group. This suggests that, at least in this limited number of patients, the lower overall survival of survivin-positive patients may be due to a combination of higher relapse rates and a poor efficiency of salvage treatment. Although age was not identified as a predictive factor, it should be considered that patients of 70 years and older who did not receive an anthracycline-based regimen were withdrawn from the study, thus reducing the potential number of patients over 60 years of age.

The observation that survivin expression influenced overall survival but did not predict response to treatment suggests that residual tumor cells in patients in CR may have a growth advantage when survivin is present. This is consistent with the cell cycle–regulated expression of the survivin gene during mitosis17 and its role in inhibition of apoptosis at G2/M.18 Consistent with a general role of this mechanism in cancer progression,16survivin expression correlated with aggressive forms of neuroblastoma,19,23 abbreviated survival rates in colorectal20,22 and lung cancer,21 and increased rate of recurrences in bladder cancer.32Moreover, overexpression of survivin counteracted apoptosis induced by a variety of stimuli in vitro33 and was associated with considerably reduced apoptotic indices in gastric and colorectal cancers in vivo.20,34 Concerning large-cell lymphoma, it is intriguing that expression of both survivin (this study) andbcl-2 7-10 correlated with abbreviated survival rates, thus emphasizing how dysregulation of apoptosis may dramatically influence disease outcome. Functionally, bcl-2 and survivin have been positioned in nonoverlapping antiapoptotic pathways, with preservation of mitochondrial integrity bybcl-2 35 and interference with caspase activation/function by survivin.14 It is therefore plausible that expression of bcl-2 and survivin may synergistically provide nonredundant cytoprotective signals in large-cell lymphoma, affording broad resistance to multiple death-inducing pathways initiated by radiation or chemotherapeutic agents.33 36

In summary, we have identified survivin as a new independent prognostic factor for poor outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Combined with bcl-2 overexpression,7-10 and p53 mutations,11,12 these findings may provide a new molecular framework to identify patients harboring aggressive B-cell lymphomas.6 On the other hand, molecular targeting ofbcl-2 and survivin improved disease in vivo37and caused spontaneous apoptosis in vitro,18 thus suggesting that manipulation of this antiapoptotic pathway may offer a potential therapeutic strategy to achieve stable remissions in lymphoma.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Catherine Balmale, Antoine Allain, and Catherine Belorgey for expert assistance with data management. The authors thank the following clinicians and pathologists who actively participated in the study: I. Abdalsamad, R. Angonin, B. Audhuy, J. Audouin, A. C. Baglin, P. Bensimon, F. Berger, P. Biron, M. Blanc, F. Boman, A. Boehn, J. Boniver, D. Bordessoule, A. Bosly, R. Bouabdallah, J. Bouvier, P. Brice, J. Brière, N. Brousse, J. P. Carbillet, D. Cazals, a.m. Chesneau, B. Christian, B. Coiffier, E. Deconinck, M. Delos, G. Delsol, M. Divine, C. Doyen, H. Duplay, B. Dupriez, C. Duval, J. C. Eisenmann, J. M. Emberger, J. P. Fermand, Y. Fonck, N. Froment, J. Gabarre, O. Gasser, B. Gosselin, H. Guy, J. Hamels, R. Herbrecht, O. Hopfner, N. Horschowski, R. Jeandel, J. P. Knopf, C. Lavignac, M. Lecomte-Houcke, P. Lederlin, R. Loire, R. Marcellin, G. Marit, C. Martin, C. Marty-Double, A. de Mascarel, C. Merignargues, F. Morvan, J. F. Mosnier, G. Nedellec, C. Nouvel, N Patey, P. Y. Peaud, G. Perie, M. Peuchmaur, T. Petrella, B. Pignon, J. P. Pollet, M. Raphael, M. C. Raymond-Gelle, M. Rochet, A. Rozenbaum, C. Sebban, S. Thiebaut, A. Thyss, H. Tilly, P. Travade, and L. Xerri.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA78810 and CA82130 (D.C.A.). Supported in part by grants of the French Ministry of Health (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique), the Délégation á la Recherche Clinique de l'AP-HP, and the Ligue contre le Cancer, France. C.A. is a fellow of the Lymphoma Research Foundation of America.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Dario C. Altieri, Yale University School of Medicine, BCMM436B, 295 Congress Ave, New Haven, CT 06536; e-mail:dario.altieri@yale.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal