Abstract

Activating transcription factor (ATF) 3 is a member of ATF/cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)–responsive element binding protein (ATF/CREB) family of transcription factors and functions as a stress-inducible transcriptional repressor. To understand the stress-induced gene regulation by homocysteine, we investigated activation of the ATF3 gene in human endothelial cells. Homocysteine caused a rapid induction of ATF3 at the transcriptional level. This induction was preceded by a rapid and sustained activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK), and dominant negative mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 and 7 abolished these effects. The effect of homocysteine appeared to be specific, because cysteine or homocystine had no appreciable effect, but it was mimicked by dithiothreitol and β-mercaptoethanol as well as tunicamycin. The homocysteine effect was not inhibited by an active oxygen scavenger. Deletion analysis of the 5′ flanking sequence of the ATF3 gene promoter revealed that one of the major elements responsible for the induction by homocysteine is an ATF/cAMP responsive element (CRE) located at −92 to −85 relative to the transcriptional start site. Gel shift, immunoprecipitation, and cotransfection assays demonstrated that a complex (or complexes) containing ATF2, c-Jun, and ATF3 increased binding to the ATF/CRE site in the homocysteine-treated cells and activated the ATF3 gene expression, while ATF3 appeared to repress its own promoter. These data together suggested a novel pathway by which homocysteine causes the activation of JNK/SAPK and subsequent ATF3 expression through its reductive stress. Activation of JNK/SAPK and ATF3 expression in response to homocysteine may have a functional role in homocysteinemia-associated endothelial dysfunction.

Introduction

Elevated blood levels of homocysteine are associated with an increased risk of vascular diseases, such as arterial and venous thrombosis and arteriosclerosis.1-5For example, patients with severe homocysteinemia resulting from an inherited disorder of methonine metabolism exhibit significant vascular diseases in childhood.2 Homocysteine has been reported to influence several aspects of metabolism in cellular components of vascular wall. It perturbs endothelial cell functions by enhancing expression of tissue factor6 and factor V,7 or by reducing production of activated protein C,8thrombomodulin activity,9 von Willebrand factor,10 anti-thrombin III binding to anticoagulant heparan sulfate on cell,11 and binding sites for tissue plasminogen activator.12 It also increases the affinity of apolipoprotein(a) for fibrin.13 In smooth muscle cells, homocysteine has a positive effect on cyclin A gene transcription, thus stimulating smooth muscle cell proliferation, which is a hallmark of arteriosclerosis.14 15

It has been argued that homocysteine causes these multifold effects through the reactivity of its sulfhydryl group. For example, homocysteine affects folding of proteins by reducing disulfide bonds, thus impairing their function or preventing their export from endoplasmic reticulum (ER).16-18 In addition, with catalytic help from the copper ion, homocysteine produces superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, which injure cells by oxidative stress.4,5 These processes involve activation of signal transduction pathway(s) as well as a cascade of gene expression. An understanding of these processes at the molecular level is required to elucidate the mechanism of cell injury by homocysteine. Recently, dramatically altered gene expression has been reported in endothelial cells exposed to homoysteine.16-18 Among up-regulated genes are glucose responsive protein (GRP) 78/immunoglobulin binding protein (Bip), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)–dependent methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase, activating transcription factor (ATF) 4, reducing agents and tunicamycin-responsive protein, Herp, and a few novel genes. GRP78/Bip is an ER-resident chaperon that is induced by agents or conditions known to elicit ER stress.16-18 Thus, it is suggested that homocysteine alters the cellular redox state and causes ER stress. However, we have limited knowledge of the cellular responses to homocysteine in terms of signal transduction and gene expression that are not directly linked to the expression of resident ER protein.

Members of the ATF/cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) responsive element binding (CREB) family of transcription factors recognize a consensus DNA sequence, TGACGTCA; have structurally similar basic region/leucine zipper domains; and interact selectively with each other to form heterodimers through their leucine zipper region.19-22 Members of the ATF1/CREB subfamily contain similar phosphorylation sites and stimulate transcription in response to cAMP or calcium influx.23-25 In contrast, members of the ATF2/CRE-binding protein 1 (CRE-BP1) subfamily share similarity in the first 100 N-terminal and the last 13 C-terminal residues but do not have A-kinase consensus sites. ATF3, a member of the ATF2/CRE-BP1 subfamily, is thus unresponsive to elevated cAMP, but is induced by stress stimuli such as carbon tetrachloride, ischemia/reperfusion, and convulsion.20,26,27 It is also highly induced in regenerating-liver or adenovirus-E1–transformed cells.28,29 Although ATF3 functions as a transcriptional repressor,26 its biological significance has not been well defined.

In this study, we investigated the ATF3 gene induction in endothelial cells exposed to homocysteine and identified the cis-element of the gene responsible for the induction. We also showed that homocysteine activated the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) signaling pathway through its reductive stress. The significance of the stress-induced ATF3 gene expression and its involvement in the homocysteine toxicity are discussed.

Materials and methods

Reagents and plasmids

dl-homocysteine, l-homocystine,l-cysteine, l-cystine, dithiothreitol,N-acetyl-l-cysteine, tunicamycin, and actinomycin D were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); yeast hexokinase was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Inc (Osaka, Japan); and β-mercaptoethanol was from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). Endothelial growth medium 2 (EGM-2) medium was from Clonetics Corp (San Diego, CA). Kinase inhibitors PD98059 and SB203580 were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Rabbit antibodies against ATF2, ATF3, ATF4, c-Jun, JNK, and phosphorylated JNK were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-p38 and antiphosphorylated p38 antibodies were from New England Biolabs Inc (Boston, MA), and Texas Red–conjugated goat antirabbit or antimouse immunoglobulin (Ig)–G antibodies were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Calf intestine alkaline phosphatase was the product of Takara Shuzo Co (Shiga, Japan), and pATF3CAT and pETATF3 were kindly provided by Dr T. Hai (Columbus, Ohio). Mammalian expression plasmid for human ATF3, pCIATF3, was prepared by subcloning full-length ATF3 complementary DNA (cDNA) into pCIneo vector (Promega, Madison, WI). Expression plasmids for dominant negative mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MKK) 4/SAPK/ERK kinase 1 and MKK7 were prepared by subcloning into pEGFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Expression plasmids for ATF2, ATF4, and c-Jun were gifts from Dr K. Oda (Tokyo, Japan). All other chemicals were of reagent grade.

Cell culture, stimulation by homocysteine, and RNA preparation

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs), passages of 2 to 6, were obtained from Clonetics Corp. Cells were grown in EGM-2 medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 μg/mL gentamicin, 50 ng/mL amphotericin, and a mixture of growth factors as in supplier's protocol at 37°C in a 5% CO2–humidified incubator. When the cells reached 70% to 80% confluency in a 60-mm dish (5 × 105 cells), they were treated with the indicated concentration of homocysteine. After adequate periods of incubation, total RNA was isolated by an acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction method with the use of Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). The amounts of RNA were quantitated by measuring optical density at 260 nm.

Northern blot

Total RNA (10 μg) was denatured and separated on a 1% agarose gel in 10 mmol/L sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The RNA was then transferred onto a Hybond-N+ nylon-membrane (Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, UK) and baked at 80°C for 2 hours. The membrane was prehybridized in Rapid-hyb solution (Amersham Life Science) at 42°C for 2 hours and then hybridized with radiolabeled cDNA probe at 42°C for 2 hours. After washing twice in 0.1 × SSC/0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 65°C for 20 minutes, the membrane was exposed and analyzed by Bas 2500 Bio-image analyzer (Fujifilm Co, Tokyo, Japan). DNA sequences for full-length human ATF3 and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 540 base pairs (bp) and 1.2 kilobases, respectively, were radiolabeled with [α-32P] deoxycytidine triphosphate (6000 Ci/mmol, Amersham) with the use of a random primer-labeling kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan) and were used as probes.

Nuclear run-on assay

HUVECs (1 × 107cells) were treated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine for 1 and 2 hours. Cells were collected and treated in 1 mL of NP-40 lysis buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mmol/L NaCl, 3 mmol/L MgCl2, and 0.5% NP-40) at 4°C for 10 minutes, and their nuclei were pelleted at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes. The lysis procedure was repeated twice, and the nuclei were resuspended in 100 μL of storage buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.1 mmol/L EDTA, and 40% glycerol) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Elongation of nascent RNA chains was initiated by mixing the above nuclear suspension with 100 μL of reaction buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 300 mmol/L KCl, 0.5 mmol/L each of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), cytidine 5′-triphosphate, guanosine 5′-triphosphate, and 100 μCi of α-32P] uridine triphosphate (3000 Ci/mmol, Amersham) and incubating at 30°C for 30 minutes. RNA synthesis was terminated by incubation with 5 μg/mL RNase-free DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) at 30°C for 10 minutes. The mixture was then digested with proteinase K (200 μg/mL) in 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mmol/L EDTA, and 1% SDS at 50°C for 1 hour and extracted twice with phenol-chloroform after adding 30 μg transfer RNA as a carrier. Radiolabeled RNA was further purified by ethanol precipitation and dissolved in 100 μL of 50% formamide, 5 × SSC, 5 × Denhardt's solution, and 0.1% SDS. Approximately 20 μg of human ATF3 and GAPDH cDNA were immobilized on a Hybond-N membrane with the use of a slot-blot apparatus. After denaturation, baking, and prehybridization of the membrane with Rapid-hyb solution, it was hybridized with radiolabeled RNA at 42°C overnight. The membranes were washed twice in 0.1 × SSC/0.1% SDS at 65°C for 20 minutes and analyzed by Bas 2500 Bio-image analyzer.

Preparation of whole-cell extracts

Whole-cell extracts from the homocysteine-treated HUVECs were obtained as follows. Briefly, cells (1.5 × 106 cells) were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in 50 μL of lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L egtazic acid, 0.1 mmol/L phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 μg/mL each leupeptin and aprotinin, 200 μmol/L sodium vanadate, 100 mmol/L NaF, and 10% glycerol), and incubated on ice for 10 minutes. The cells were centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was taken as whole-cell extract. The amounts of protein were quantitated by Lowry method.30

Western blot

We separated 20 μg of whole-cell extracts from the homocysteine-treated HUVECs on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred it onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with PBS containing 5% skimmed milk, the membrane was incubated with the indicated primary antibody in the same buffer. After washing, the membrane was further incubated with alkaline phosphatase–conjugated anti-IgG antibody. The reacted band was visualized by chemiluminescence as in the protocol from Tropix Inc (Bedford, MA).

Immunostaining of cells

HUVECs grown and treated as described in the figure legends were fixed by immersion in cold acetone/methanol (1:1) for 10 minutes and then rinsed with 70% ethanol, 50% ethanol, and PBS. After blocking in PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% Tween 20, and 6.7% glycerol at room temperature for 1 hour, the cells were incubated with antibody for 1 hour, washed with PBS, and sequentially incubated with fluorescence-labeled secondary antibody. For staining of nuclei, cells were treated with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan).

Construction of the reporter gene plasmids

Human ATF3 gene promoter–luciferase reporter plasmid pLuc-1850 was constructed by insertion of the promoter sequence from the −1850 to +34 region of pATF3CAT into a basic vector (PGV-B2, Toyo Ink, Tokyo, Japan) containing the firefly luciferase gene.31Deletion mutants containing various lengths of the 5′ flanking region were obtained by insertion of sequences from −632,−110, and −84 to +34 into the basic vector to obtain pLUC-632, pLUC-110, and pLUC-84, respectively. Then pLUC-1850m, which contains mutations of the ATF/cAMP responsive element (CRE) site from −92 to −85 of the gene, was prepared with the use of the plasmid pLUC-1850 as the matrix by an overlap extension polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol.32 Briefly, 2 separate PCR products, 1 for each half of the hybrid, were generated with an antisense (5′-CCAGGCTGACCAAATGCTAT-3′) or a sense (5′-ATAGCATTTGGTCAGCCTGG-3′) mutated primer and outside primers. Two products of 1740 bp and 140 bp were mixed, and the second PCR was performed with the use of the 2 outside primers. The insert was sequenced to confirm the mutations from the normal sequence of 5′-TTACGTCA-3′ to 5′-TTTGGTCA-3′.

Transient expression of the human ATF3-luciferase gene

HUVECs were grown in EGM-2 culture medium to 70% to 80% confluency in a 60-mm dish (3 × 105 cells) prior to transfection. Plasmid DNA (2 to 5 μg) was vortex-mixed with 20 μL of SuperFect (Qiagen Inc, Chatsworth, CA) in 150 μL of EGM-2; then 1 mL of EGM-2 with 2% FBS was added. The cells were exposed to this solution at 37°C for 2 hours. After replacement of the transfection solution with 2 mL of fresh medium and further incubation for 2 hours, the cells were treated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine for 4 hours. The medium was then changed to 2 mL of fresh EGM-2 without homocysteine, and the cells were further incubated at 37°C for another 20 hours. Cell extracts were obtained by adding 0.4 mL of lysis buffer and centrifugation at 12 000 rpm for 1 minute, and the supernatants were assayed for firefly and sea pansy luciferase activity by means of a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). As an internal control of transfection and expression, pRL-CMV (Toyo Ink) containing the sea pansy luciferase gene was used.

Preparation of nuclear extracts of HUVECs

Nuclear extracts were prepared from the untreated or homocysteine-treated HUVECs (2 × 107 cells). Cells were washed in PBS, pelleted, and resuspended in an equal volume of lysis buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH8.0, 60 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.1 mmol/L PMSF, and 0.5% NP-40). After incubation on ice for 5 minutes, the lysates were centrifuged at 2500 rpm in a microfuge for 4 minutes. The pelleted nuclei were briefly washed with lysis buffer without NP-40 and resuspended in an equal volume of extraction buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH8.0, 420 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.2 mmol/L EDTA, and 25% glycerol); then 5 mol/L NaCl was added to a final concentration of 400 mmol/L. After further incubation on ice for 10 minutes, the nuclei were briefly vortexed and centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 5 minutes. The supernatant was used as nuclear extract.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extracts (2 μg of protein) of the control and homocysteine-treated HUVECs were incubated in a final volume of 20 μL of binding buffer (10 mmol/L Hepes-KOH, pH 7.9, 60 mmol/L KCl, 0.5 mmol/L EDTA, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L DTT, 0.1 mmol/L PMSF, 5 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol) containing 1 μg of polydI-dC and 0.5 ng of radiolabeled DNA probe at room temperature for 30 minutes. For supershift assays, each antibody was added and incubated for another 30 minutes. DNA probe was obtained by annealing 0.1 μg each of oligonucleotides for sense and antisense sequences of ATF3 promoter from −99 to −69, and radiolabeled with either 25 μCi γ-32P] ATP (6000 Ci/mmol) and 10 U polynucleotide kinase or 50 μCi α-32P] deoxyadenosine triphosphate (6000 Ci/mmol) and 2 U Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase. Mutant oligonucleotides used for the competition experiment contained substitutions in the normal sequence of 5′-TTACGTCA-3′ to yield 5′-TTTGGTCA-3′. For in vitro dephosphorylation, nuclear extract was first pre-incubated in the binding buffer with 5 mmol/L glucose and 1 U hexokinase in order to deplete endogenous ATP, and then incubated with 2.2 unit of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase for 30 minutes. Binding mixture was applied onto a 4% or 5% polyacrylamide slab gel in Tris-borate EDTA buffer. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried on a 3MM Whatmann paper and visualized by Fuji Bas 2500 image analyzer.

Immunoprecipitation

Nuclear extracts (60 μg of protein) prepared from the control cells and cells treated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine for 4 hours were incubated with 1 μg anti-ATF2 antibody in 100 μL of immunoprecipitation buffer (20 mmol/L Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 100 mmol/L KCl, 6 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L DTT, 0.5% NP-40, 0.1 mmol/L PMSF, 10 μg/mL each of antipain and leupeptine) at 4°C for 1 hour with gentle rocking. After addition of 20 μL of 50% (vol/vol) protein G-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK) and further incubation at 4°C for 1 hour, the immune complexes were precipitated and washed 3 times. Specific proteins in the immune complexes were dissociated with 20 μL of IP buffer containing 0.8% deoxycholate and 1.2% NP-40. After centrifugation, 3 μL of the supernatants were analyzed by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting.

Data analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Student pairedt tests, and P values were shown.

Results

Induction of ATF3 gene expression by homocysteine

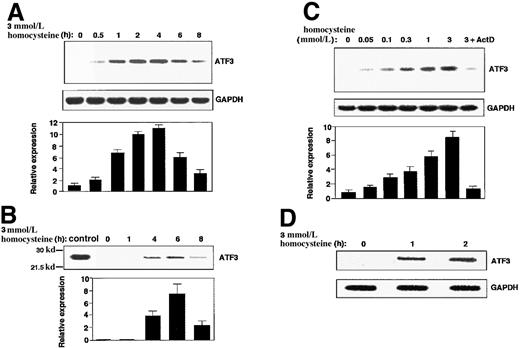

As shown in Figure 1A, treatment of HUVECs with homocysteine caused a rapid induction of ATF3 gene expression. The mRNA level reached its maximum in 2 to 4 hours, then gradually decreased up to 8 hours. Western blot analysis revealed that the ATF3 protein was also induced 4 to 6 hours after exposure (Figure1B). When the concentration of homocysteine was titrated, it was found that a relatively high dose of homocysteine (1 to 3 mmol/L) was required for the maximum induction, although significant induction was observed at lower concentrations (0.05 to 0.3 mmol/L) (Figure 1C). Since the induction of ATF3 mRNA was almost abolished by pretreatment of cells with actinomycin D (Figure 1C; 3+ActD), we next performed a nuclear run-on assay. Figure 1D shows that nuclei from the homocysteine-treated cells exhibited higher activity of the ATF3 gene transcription than those from the control cells. These data clearly indicated that ATF3 is one of the immediate early responsive genes activated by homocysteine and its induction is regulated mainly at a transcriptional level.

ATF3 gene induction by homocysteine in HUVECs.

(A,B) Cultured HUVECs were incubated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine for the indicated time, and messenger RNA (mRNA) (panel A) and protein (panel B) level of ATF3 and GAPDH were measured by Northern blot and Western blot, respectively, as described in “Materials and methods.” The relative expression was shown in arbitrary units, and results were means of 3 independent experiments with SE bar. Bacterially expressed ATF3 protein was used as a control in Western blot (control). (C) ATF3 mRNA in the cells exposed to different concentrations of homocysteine for 4 hours was measured as in panel A. In lane 7, cells were preincubated with 10 μg/mL actinomycin D for 2 hours, then stimulated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine. (D) Nuclear run-on assay was performed with the use of nuclei from the homocysteine-stimulated cells for 1 and 2 hours, and their elongated transcripts were hybridized to ATF3 and GAPDH plasmid probes as described in “Materials and methods.”

ATF3 gene induction by homocysteine in HUVECs.

(A,B) Cultured HUVECs were incubated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine for the indicated time, and messenger RNA (mRNA) (panel A) and protein (panel B) level of ATF3 and GAPDH were measured by Northern blot and Western blot, respectively, as described in “Materials and methods.” The relative expression was shown in arbitrary units, and results were means of 3 independent experiments with SE bar. Bacterially expressed ATF3 protein was used as a control in Western blot (control). (C) ATF3 mRNA in the cells exposed to different concentrations of homocysteine for 4 hours was measured as in panel A. In lane 7, cells were preincubated with 10 μg/mL actinomycin D for 2 hours, then stimulated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine. (D) Nuclear run-on assay was performed with the use of nuclei from the homocysteine-stimulated cells for 1 and 2 hours, and their elongated transcripts were hybridized to ATF3 and GAPDH plasmid probes as described in “Materials and methods.”

Homocysteine-induced ATF3 gene expression involved activation of JNK/SAPK

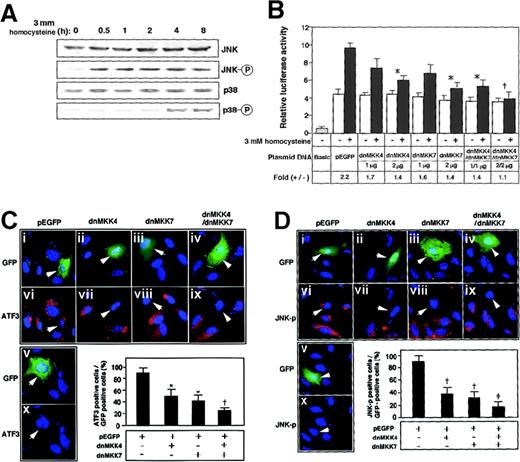

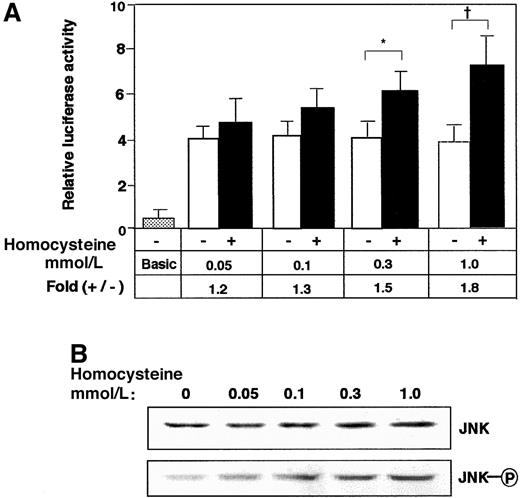

To elucidate the signal transduction by homocysteine, the effects of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase inhibitors were examined. Neither p38 kinase–specific inhibitor SB203580 nor extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK)–specific inhibitor PD98059, alone or in combination, had any inhibitory effect (data not shown). As shown in Figure 2A, Western blotting demonstrated that JNK/SAPK and p38 MAP kinase were phosphorylated after the homocysteine treatment. Intriguingly, the phosphorylation of JNK/SAPK was rapid and sustained longer; it occurred within 30 minutes and persisted for at least 8 hours. In contrast, the activation of p38 was observed only after prolonged exposure to homocysteine (4 to 8 hours). We next studied the homocysteine-responsive ATF3 gene transcription by means of a reporter assay. As shown in Figure 2B, the 1850-bp region of the 5′ flanking sequence fused to the luciferase reporter gene exhibited approximately 2-fold induction by homocysteine. This induction was not affected by MAP-kinase inhibitors specific for p38 and ERK MAP kinase (data not shown). Upon coexpression of the dominant negative MKK4 and 7, which are upstream MKKs for JNK/SAPK, the homocysteine-responsive activation of the reporter gene was inhibited. In Figure 2C-D, the activation of ATF3 and JNK/SAPK by homocysteine was examined in cells transfected with dominant negative MKK4 and 7. Homocysteine clearly induced the ATF3 expression (Figure2Cvi-x) and activated JNK/SAPK (Figure 2Dvi-x). Under this condition, dominant negative MKK4 and 7 inhibited the induction of ATF3 protein as well as the activation of JNK/SAPK. These data strongly suggested that the ATF3 gene induction by homocysteine was mediated at least in part by the activation of JNK/SAPK through cascade signals from MKK4 and 7. We next assayed the homocysteine effect using the pathophysiologic concentration of 0.05 to 0.3 mmol/L. The induction of ATF3 gene in the reporter assay (Figure 3A) and the phosphorylation of JNK/SAPK (Figure 3B) were observed, while statistically significant activation was observed at 0.3 mmol/L homocysteine, which is a serum concentration in severe cases of homocysteinemia.

ATF3 gene induction by homocysteine involved activation of JNK/SAPK signaling pathway.

(A) HUVECs were treated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine for the indicated time, and their whole-cell extracts (40 μg) were subjected to Western blot with anti-JNK/SAPK (JNK), anti-phospho JNK/SAPK (JNK-○P), anti-p38 (p38), or anti-phospho p38 (p38-○P) antibody. (B) HUVECs were transfected with 2 μg of pLuc-1850 reporter plasmid and 1 or 2 μg of plasmids for dominant negative (dn) MKK4, dnMKK7, or both. The cells were incubated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine for 4 hours and then without homocysteine for 16 hours; then promoter activity was assayed as described in “Materials and methods.” Relative luciferase activity is expressed in arbitrary units; the results are the average of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar. Fold induction is the ratio of homocysteine-stimulated activity (solid columns) to that without homocysteine (open columns). Basic and pEGFP represent the reporter plasmid without ATF3 gene promoter and the empty vector for dnMKK4 and 7, respectively. Fold induction was compared with that of the control pEGFP vector; *P < .05, †P < .01, n = 3. (C,D) HUVECs were transfected with plasmids for the empty vector (i, vi), dnMKK4 (ii, vii), dnMKK7 (iii, viii), or both (iv, ix) and then stimulated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine. ATF3 expression and activation of JNK/SAPK were detected by immunostaining with anti-ATF3 (panel C) and anti-phospho JNK/SAPK (panel D) antibodies in the transfected cells, which were detected by green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence (indicated by arrows in i-v). Cells were transfected with the empty vector but not treated by homocysteine (v, x). In the lower panels, ATF3-positive cells (panel C) or JNK-○P–positive cells (panel D) are expressed as a percentage of transfected GFP-positive cells. The data represent the means of 3 independent experiments with SE bars. Statistically significant inhibition from the control pEGFP vector; *P < .05, †P < .01, ‡P < .001, n = 3.

ATF3 gene induction by homocysteine involved activation of JNK/SAPK signaling pathway.

(A) HUVECs were treated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine for the indicated time, and their whole-cell extracts (40 μg) were subjected to Western blot with anti-JNK/SAPK (JNK), anti-phospho JNK/SAPK (JNK-○P), anti-p38 (p38), or anti-phospho p38 (p38-○P) antibody. (B) HUVECs were transfected with 2 μg of pLuc-1850 reporter plasmid and 1 or 2 μg of plasmids for dominant negative (dn) MKK4, dnMKK7, or both. The cells were incubated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine for 4 hours and then without homocysteine for 16 hours; then promoter activity was assayed as described in “Materials and methods.” Relative luciferase activity is expressed in arbitrary units; the results are the average of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar. Fold induction is the ratio of homocysteine-stimulated activity (solid columns) to that without homocysteine (open columns). Basic and pEGFP represent the reporter plasmid without ATF3 gene promoter and the empty vector for dnMKK4 and 7, respectively. Fold induction was compared with that of the control pEGFP vector; *P < .05, †P < .01, n = 3. (C,D) HUVECs were transfected with plasmids for the empty vector (i, vi), dnMKK4 (ii, vii), dnMKK7 (iii, viii), or both (iv, ix) and then stimulated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine. ATF3 expression and activation of JNK/SAPK were detected by immunostaining with anti-ATF3 (panel C) and anti-phospho JNK/SAPK (panel D) antibodies in the transfected cells, which were detected by green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence (indicated by arrows in i-v). Cells were transfected with the empty vector but not treated by homocysteine (v, x). In the lower panels, ATF3-positive cells (panel C) or JNK-○P–positive cells (panel D) are expressed as a percentage of transfected GFP-positive cells. The data represent the means of 3 independent experiments with SE bars. Statistically significant inhibition from the control pEGFP vector; *P < .05, †P < .01, ‡P < .001, n = 3.

Effect of lower concentration of homocysteine on the ATF3 gene expression in reporter assay and phosphorylation of JNK/SAPK.

(A) HUVECs transfected with 2 μg of pLuc-1850 reporter plasmid were stimulated with the indicated concentration of homocysteine as in Figure 2B, and ATF3 promoter activity was assayed as described in “Materials and methods.” The results are the average of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar. Basic represents the reporter plasmid without ATF3 gene promoter. Statistically significant fold induction was found in the presence of homocysteine; *P < .05, †P < .01, n = 3. (B) HUVECs were treated with the indicated concentration of homocysteine for 2 hours, and the whole-cell extracts (40 μg) were analyzed by Western blot with anti-JNK/SAPK (JNK) or anti-phospho JNK/SAPK antibody (JNK-○P).

Effect of lower concentration of homocysteine on the ATF3 gene expression in reporter assay and phosphorylation of JNK/SAPK.

(A) HUVECs transfected with 2 μg of pLuc-1850 reporter plasmid were stimulated with the indicated concentration of homocysteine as in Figure 2B, and ATF3 promoter activity was assayed as described in “Materials and methods.” The results are the average of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar. Basic represents the reporter plasmid without ATF3 gene promoter. Statistically significant fold induction was found in the presence of homocysteine; *P < .05, †P < .01, n = 3. (B) HUVECs were treated with the indicated concentration of homocysteine for 2 hours, and the whole-cell extracts (40 μg) were analyzed by Western blot with anti-JNK/SAPK (JNK) or anti-phospho JNK/SAPK antibody (JNK-○P).

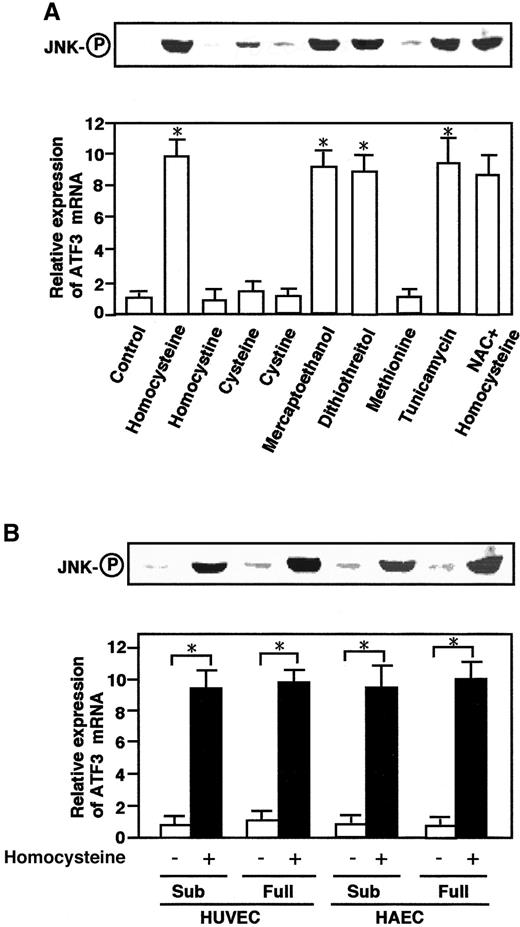

Effects of other thiol-containing compounds and tunicamycin

To investigate specificity of the homocysteine-induced activation of JNK/SAPK and ATF3, the effects of other thiol-containing reagents and tunicamycin were examined. As shown in Figure4A, dithiothreitol and β-mercaptoethanol exhibited significant effects, while cysteine had only a marginal effect. By contrast, homocystine, the disulfide form of homocysteine, had essentially no effect, indicating that the sulfhydryl group was important for the effect. Tunicamycin, a glycosylation inhibitor and potent inducer of ER stress, significantly activated the JNK/SAPK and ATF3 expression.N-acetyl-l-cysteine, an active oxygen scavenger, had no inhibitory effect on the homocysteine effect. These data together indicated that the effect of homocysteine was mediated through the reactivity of its thiol group, could be mimicked by ER stress, and did not involve the generation of reactive oxygen species.

Effects of other thiol-containing compounds and tunicamycin on ATF3 mRNA and JNK/SAPK and in aortic endothelial cells.

(A) HUVECs were treated with 3 mmol/L each of the indicated compounds or 10 μg/mL tunicamycin for 4 hours, and their total RNA and whole-cell extracts were assayed for ATF3 mRNA and phosphorylated JNK/SAPK (JNK-○P), respectively, as in Figures 1 and 2. For the NAC effect, cells were pretreated with 20 mmol/LN-acetyl-l-cysteine for 1 hour. There was statistically significant activation from the control; *P < .0001, n = 3. (B) Both subconfluent (sub) and confluent HUVECs or HAECs were incubated in the absence (open columns) or presence (solid columns) of 3 mmol/L homocysteine for 4 hours, and their ATF3 expression and phosphorylation of JNK/SAPK (JNK-○P) were measured as in panel A. In both panel A and panel B, the relative expression of ATF3 mRNA is given in arbitrary units and represents the mean of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar. Statistically significant activation was found in the presence of homocysteine; *P < .0001, n = 3.

Effects of other thiol-containing compounds and tunicamycin on ATF3 mRNA and JNK/SAPK and in aortic endothelial cells.

(A) HUVECs were treated with 3 mmol/L each of the indicated compounds or 10 μg/mL tunicamycin for 4 hours, and their total RNA and whole-cell extracts were assayed for ATF3 mRNA and phosphorylated JNK/SAPK (JNK-○P), respectively, as in Figures 1 and 2. For the NAC effect, cells were pretreated with 20 mmol/LN-acetyl-l-cysteine for 1 hour. There was statistically significant activation from the control; *P < .0001, n = 3. (B) Both subconfluent (sub) and confluent HUVECs or HAECs were incubated in the absence (open columns) or presence (solid columns) of 3 mmol/L homocysteine for 4 hours, and their ATF3 expression and phosphorylation of JNK/SAPK (JNK-○P) were measured as in panel A. In both panel A and panel B, the relative expression of ATF3 mRNA is given in arbitrary units and represents the mean of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar. Statistically significant activation was found in the presence of homocysteine; *P < .0001, n = 3.

Effects of homocysteine in aortic endothelial cells

We next examined the effect of homocysteine in HAECs. As shown in Figure 4B, homocysteine activated the JNK/SAPK and ATF3 expression in HAECs as well as in HUVECs. It should be noted that human endothelial cells are quiescent in vivo. Thus, the effects of homocysteine were examined in confluent cells. Almost similar effects were observed in both subconfluent and confluent cells. Therefore, the homocysteine effect appeared to be independent of the proliferative activity of the cells.

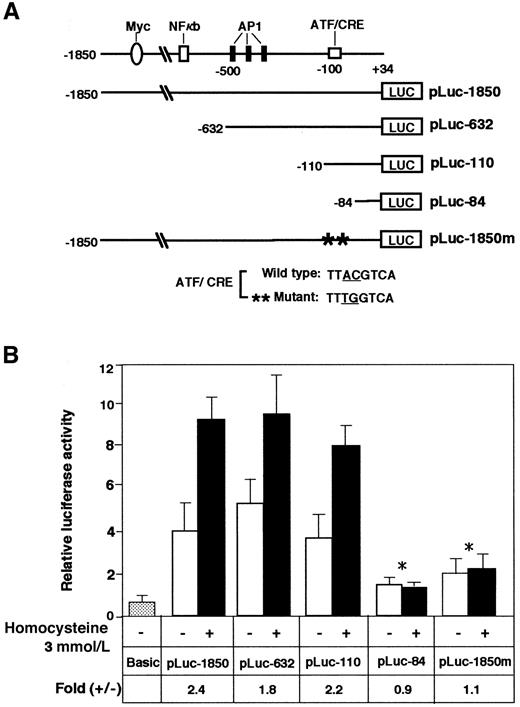

Homocysteine-responsive element of ATF3 gene promoter

To determine the homocysteine-responsive element(s) of the ATF3 gene promoter, we next analyzed plasmid constructs containing sequential deletions by reporter assay. Figure5 shows that the deletion mutants from −1850 to −110 were as active as the original construct in responding to homocysteine. In contrast, further deletion to −84 nearly abolished the activation by homocysteine. The region from −92 to −84 of the ATF3 promoter contains an ATF/CRE sequence, TTACGTCA, that differs from the consensus sequence TGACGTCA in only one base. We next introduced 2 mutations into the ATF/CRE site of pLuc-1850 and assayed its inducibility by homocysteine. These mutations completely abolished the stimulation by homocysteine. Thus, the ATF/CRE site represents one of the major elements responsible for ATF3 gene induction by homocysteine.

Analysis of the ATF3 gene promoter element required for activation by homocysteine.

(A) Scheme of the 5′-deletion constructs of the human ATF3 gene promoter fused to the luciferase gene. At the top, putative elements of the ATF3 gene promoter are shown.30 The numbers shown on the ATF3 promoter-luciferase cDNA constructs indicate the 5′-end positions of the promoter sequence. The construct pLuc-1850m, containing 2 base mutations in the ATF/CRE motif at −92 to −85, is shown at the bottom. (B) HUVECs were transfected with 2 μg of each plasmid and treated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine. The promoter activity was assayed as described in “Materials and methods” and expressed in arbitrary units. Fold induction is the ratio of homocysteine-stimulated activity (solid columns) to activity without homocysteine (open columns). The data represent the mean of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar. The fold induction was compared and tested with that of pLuc-1850; *P < .001, n = 3.

Analysis of the ATF3 gene promoter element required for activation by homocysteine.

(A) Scheme of the 5′-deletion constructs of the human ATF3 gene promoter fused to the luciferase gene. At the top, putative elements of the ATF3 gene promoter are shown.30 The numbers shown on the ATF3 promoter-luciferase cDNA constructs indicate the 5′-end positions of the promoter sequence. The construct pLuc-1850m, containing 2 base mutations in the ATF/CRE motif at −92 to −85, is shown at the bottom. (B) HUVECs were transfected with 2 μg of each plasmid and treated with 3 mmol/L homocysteine. The promoter activity was assayed as described in “Materials and methods” and expressed in arbitrary units. Fold induction is the ratio of homocysteine-stimulated activity (solid columns) to activity without homocysteine (open columns). The data represent the mean of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar. The fold induction was compared and tested with that of pLuc-1850; *P < .001, n = 3.

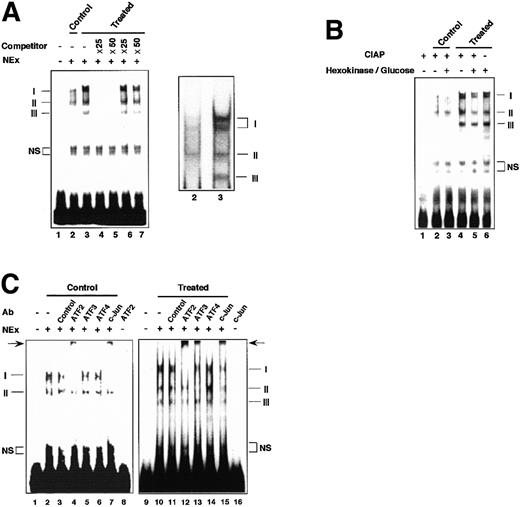

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays of nuclear extracts from homocysteine-treated HUVECs

Figure 6A shows electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using the ATF/CRE element as DNA probe. Extracts from the control cells produced 2 major bands, I and II (lane 2), while extracts from the homocysteine-treated cells exhibited markedly increased intensity of bands I and II with an appearance of a new band, band III (lane 3). Band I was composed of 2 bands of close mobility, of which the upper band appeared only after homocysteine treatment. Bands I, II, and III were all competed out by an oligonucleotide with the wild-type sequence (lanes 4 and 5), but not by a mutated oligonucleotide (lanes 6 and 7), indicating that these 3 bands were all specific. As shown in Figure 6B, dephosphorylation of extracts from the homocysteine-treated cells markedly reduced the intensity of bands I and II and slightly reduced that of band III, suggesting that modification by phosphorylation of factors could, at least in part, account for the increased binding in the homocysteine-treated cells. Incubation of the control extracts with homocysteine or incubation of the homocysteine-treated extracts with β-mercaptoethanol in vitro did not alter their EMSA patterns (data not shown). Next, we examined the composition of DNA-protein complexes by supershift assay. As shown in Figure 6C, anti-ATF2 antibody produced a strong supershifted band with concomitant reduction of bands I and II in both the unstimulated and stimulated cells (lanes 4 and 12). Band III in the stimulated cells was also supershifted by anti-ATF2 antibody (lane 12). Among another antibodies tested, anti–c-Jun antibody produced a supershifted band in both types of cells (lanes 7 and 15), and anti-ATF3 antibody supershifted only in the stimulated cells (lane 13). Control antibody did not produce apparent supershifted bands (lanes 3 and 11), and no antibody tested recognized the ATF/CRE probe in the assay (lanes 8 and 16). Anti-ATF4 antibody did not produce an apparent supershifted band, although it has been reported that ATF4 is induced by homocysteine.16 Taken together, these data demonstrated that ATF2 and c-Jun are involved in recognizing the ATF/CRE site of the gene promoter in the control cells, and these factors are activated to increase the binding in the homocysteine-treated cells. Our results further indicate that the ATF3 protein is recruited into the activated complex(es) in the homocysteine-stimulated cells.

EMSAs of complexes formed with the ATF/CRE motif of the ATF3 gene promoter.

(A) Nuclear extracts (NEx) from the control or homocysteine-treated HUVECs were subjected to EMSAs as described in “Materials and methods.” Lane 1, probe only; lane 2, control extract; lanes 3, 4, and 5, homocysteine-treated extract incubated in the absence (3) or presence of 25- (4) or 50-fold (5) molar excess of wild-type oligonucleotide; lanes 6 and 7, same as lanes 4 and 5, but in the presence of mutated oligonucleotide. Bands I, II, and III indicate specific complexes, and NS indicates nonspecific bands. In the right figure, 2 closely migrating components of band I are shown. (B) Nuclear extracts from the control and homocysteine-stimulated cells were dephosphorylated in vitro as described in “Materials and methods.” Lane 1, probe and calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP); lanes 2 and 3, control extract without or with pretreatment by hexokinase and glucose, respectively; lanes 4 and 5, homocysteine-treated extract without and with hexokinase/glucose pretreatment, respectively; lane 6, homocysteine-treated extract with hexokinase/glucose pretreatment but without CIAP treatment. (C) Binding assay was performed in the presence of 0.1 to 0.2 μg of antibody specific for the indicated factors with the use of the control extract (lanes 1-8) and extract from the homocysteine-treated cells (lanes 9-16). Lanes 1 and 9, probe only; lanes 2 and 10, nuclear extract only; lanes 3 and 11, control IgG; lanes 4 and 12, anti-ATF2 antibody; lanes 5 and 13, anti-ATF3 antibody; lanes 6 and 14, anti-ATF4 antibody; lanes 7 and 15, anti–c-Jun antibody; lanes 8 and 16, probe with anti-ATF2 and anti–c-Jun antibody, respectively. Arrow indicates the supershifted band by anti-ATF2, anti-ATF3, and anti–c-Jun antibody.

EMSAs of complexes formed with the ATF/CRE motif of the ATF3 gene promoter.

(A) Nuclear extracts (NEx) from the control or homocysteine-treated HUVECs were subjected to EMSAs as described in “Materials and methods.” Lane 1, probe only; lane 2, control extract; lanes 3, 4, and 5, homocysteine-treated extract incubated in the absence (3) or presence of 25- (4) or 50-fold (5) molar excess of wild-type oligonucleotide; lanes 6 and 7, same as lanes 4 and 5, but in the presence of mutated oligonucleotide. Bands I, II, and III indicate specific complexes, and NS indicates nonspecific bands. In the right figure, 2 closely migrating components of band I are shown. (B) Nuclear extracts from the control and homocysteine-stimulated cells were dephosphorylated in vitro as described in “Materials and methods.” Lane 1, probe and calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP); lanes 2 and 3, control extract without or with pretreatment by hexokinase and glucose, respectively; lanes 4 and 5, homocysteine-treated extract without and with hexokinase/glucose pretreatment, respectively; lane 6, homocysteine-treated extract with hexokinase/glucose pretreatment but without CIAP treatment. (C) Binding assay was performed in the presence of 0.1 to 0.2 μg of antibody specific for the indicated factors with the use of the control extract (lanes 1-8) and extract from the homocysteine-treated cells (lanes 9-16). Lanes 1 and 9, probe only; lanes 2 and 10, nuclear extract only; lanes 3 and 11, control IgG; lanes 4 and 12, anti-ATF2 antibody; lanes 5 and 13, anti-ATF3 antibody; lanes 6 and 14, anti-ATF4 antibody; lanes 7 and 15, anti–c-Jun antibody; lanes 8 and 16, probe with anti-ATF2 and anti–c-Jun antibody, respectively. Arrow indicates the supershifted band by anti-ATF2, anti-ATF3, and anti–c-Jun antibody.

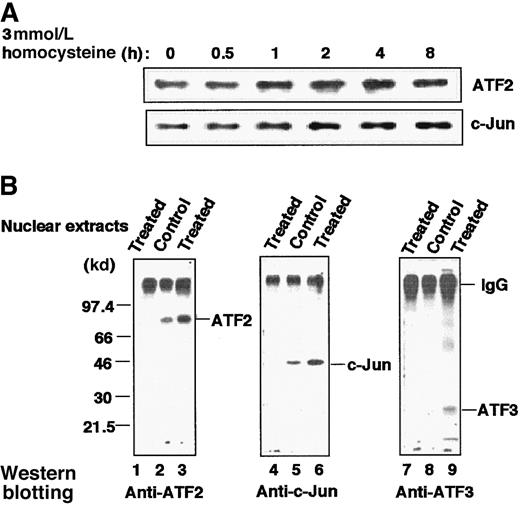

Quantitative analysis of transcription factors and their association in the homocysteine-treated HUVECs

Figure 7A shows immunoblot analysis of the whole-cell extract of homocysteine-treated cells. The amounts of ATF2 and c-Jun increased moderately after treatment. As shown in Figure1B, ATF3 protein was also induced. Thus, homocysteine up-regulated the level of transcription factors involved in recognition of the ATF/CRE site of the ATF3 gene. We next analyzed their interaction in vivo by immunoprecipitation. Figure 7B clearly demonstrates that ATF2 and c-Jun were associated with each other in both the control and stimulated cells, but the molar amounts of the 2 proteins were increased in the activated cells (lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6). In stimulated cells, ATF3 protein was recruited into the activated ATF2/c-Jun complex (lane 9), although it was present in substoichiometric amounts relative to ATF2 and c-Jun.

Increased amount of ATF2, c-Jun, and ATF3 proteins and their association in HUVECs stimulated by homocysteine.

(A) Cultured HUVECs were exposed to 3 mmol/L homocysteine for the indicated time, and their whole-cell extracts (20 μg) were subjected to Western blot with anti-ATF2 or anti–c-Jun antibody as described in “Materials and methods.” (B) Nuclear extracts prepared from the control and homocysteine-stimulated cells for 4 hours were immunoprecipitated with anti-ATF2 antibody as described in “Materials and methods.” The resultant complexes were separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, under which IgG migrated as a protein of large molecular mass, and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-ATF2 (lanes 1-3), anti–c-Jun (lanes 4-6), or anti-ATF3 (lanes 7-9) antibody as probe. Lanes 1, 4, and 7 were results of the homocysteine-treated nuclear extracts immunoprecipitated with nonimmune IgG.

Increased amount of ATF2, c-Jun, and ATF3 proteins and their association in HUVECs stimulated by homocysteine.

(A) Cultured HUVECs were exposed to 3 mmol/L homocysteine for the indicated time, and their whole-cell extracts (20 μg) were subjected to Western blot with anti-ATF2 or anti–c-Jun antibody as described in “Materials and methods.” (B) Nuclear extracts prepared from the control and homocysteine-stimulated cells for 4 hours were immunoprecipitated with anti-ATF2 antibody as described in “Materials and methods.” The resultant complexes were separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, under which IgG migrated as a protein of large molecular mass, and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-ATF2 (lanes 1-3), anti–c-Jun (lanes 4-6), or anti-ATF3 (lanes 7-9) antibody as probe. Lanes 1, 4, and 7 were results of the homocysteine-treated nuclear extracts immunoprecipitated with nonimmune IgG.

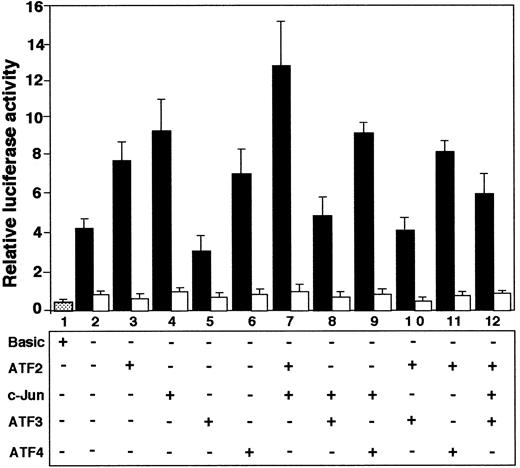

Effects of ATF and Jun family transcription factors on promoter activity of ATF3 gene

Since our results indicated that ATF2, c-Jun, and ATF3 are involved in recognizing the ATF/CRE site of the ATF3 gene, we investigated the effects of overexpression of these factors, alone or in combination, by reporter assay. Figure8 shows that both ATF2 and c-Jun, alone (lanes 3 and 4; P < .05, n = 3) or in combination (lane 7; P < .01, n = 3), activated the ATF3 gene. In contrast, ATF3 repressed both basal (lane 5; P < .05, n = 3) and ATF2/c-Jun–activated (lanes 8, 10 and 12;P < .05, n = 3) gene expression. These effects were observed when the reporter gene contained the wild-type sequence of the ATF/CRE site (solid columns), but not when the plasmid contained 2 base mutations in the element (open columns). These data indicated that ATF2 and c-Jun transactivated ATF3 promoter, but that ATF3 had a repressive effect. ATF4 stimulated ATF3 gene activity (lane 6), but had no significant effect on the activity in combination with c-Jun or ATF2 (lanes 9 and 11).

Coexpression of ATF2 and c-Jun activated ATF3 gene promoter, but ATF3 repressed it.

Cultured HUVECs were transfected with 2 μg of pLuc-1850 (solid columns) or pLuc-1850m (open columns) reporter gene along with 1 μg each of expression plasmid encoding the indicated factor. After incubation for 20 hours, the promoter activity was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” Relative luciferase activity is expressed in arbitrary units, and the data represent the mean of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar.

Coexpression of ATF2 and c-Jun activated ATF3 gene promoter, but ATF3 repressed it.

Cultured HUVECs were transfected with 2 μg of pLuc-1850 (solid columns) or pLuc-1850m (open columns) reporter gene along with 1 μg each of expression plasmid encoding the indicated factor. After incubation for 20 hours, the promoter activity was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” Relative luciferase activity is expressed in arbitrary units, and the data represent the mean of 3 independent experiments with an SE bar.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that homocysteine activated JNK/SAPK and induced the expression of ATF3 in vascular endothelial cells and that the ATF/CRE site of the ATF3 gene promoter is a major element responsible for the induction.

It should be noted that an ATF/CRE site has also been shown to mediate cyclin A gene activation by homocysteine in vascular smooth muscle cells, although the element in the cyclin A gene is recognized by ATF1 and CREB.15,33,34 The induction of the cyclin A gene was reported to be approximately 2-fold in a reporter assay,15an extent of activation similar to that of the ATF3 gene in our assay. Three families of leucine zipper proteins, CREB, ATF, and c-Jun, have been shown to bind ATF/CRE sites as a homodimer or heterodimer, thus allowing transcriptional cross-talk between different signaling pathways.20,35-38 We have shown here that the enhanced binding to the ATF/CRE site in the homocysteine-treated cells was due to an increase of phosphorylation and molar amounts of ATF2 and c-Jun. This is consistent with the fact that JNK/SAPK efficiently phosphorylates these factors39,40 and stabilizes them against breakdown by the proteasome system.41,42 Such an activation pathway has been reported for E-selectin gene activation by TNF-α in endothelial cells.43 TNF-α activates JNK/SAPK, which subsequently phosphorylates ATF2 and c-Jun, thereby up-regulating the E-selectin gene transcription through the ATF/CRE site. For the ATF3 gene, the induced ATF3 protein was recruited into the ATF2/c-Jun complex after homocysteine treatment (Figures 6C and 7). Because ATF3 repressed the ATF2/c-Jun–activated ATF3 gene promoter (Figure 8), the NF-κB/ATF2–stimulated E-selectin gene promoter,26,27 and the artificial reporter gene containing ATF/CRE sites,26 it is possible that the induced ATF3 protein represses the ATF3 gene transcription by a negative feedback mechanism (Figure 1A), which might function for cells to avoid significant accumulation of ATF3 protein. The repressive effect of the induced ATF3 protein has been reported to regulate the biphasic growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible gene 153 (GADD 153) expression in PC12 cells by arsenite.44

The fact that the activation of JNK/SAPK preceded the induction of ATF3 mRNA strongly suggested that the JNK/SAPK activation is of major functional relevance to the ATF3 induction by homocysteine. It was further shown that dominant negative MKK4 and 7 inhibited the homocysteine-induced ATF3 expression and JNK/SAPK activation (Figure2B-D). Dominant negative JNK1 and 2 had less inhibitory effect, possibly owing to their more direct involvement in the activation of ATF2 and c-Jun (data not shown). Therefore, it is intriguing to examine the specific upstream signals from homocysteine to the activation of MKK4/7. Differential regulation of MKKs by signals has already been reported.45,46 It has been proposed that homocysteine added to serum, with the catalytic help of 4 to 5 μmol/L copper ion, generates reactive oxygen species, including hydrogen peroxide, that subsequently damage endothelial cells via an oxidative process.4,5 In our experiments, however, culture medium contained far lower concentration of copper ion (8 nmol/L or less), and neither active oxygen scavenger (Figure 4A) nor exogenously added catalase (data not shown) inhibited the homocysteine-induced effects. Thus, it is considered that most of the homocysteine effect in this study was not mediated by oxidative stress. Recent works from other laboratories showed that homocysteine failed to elicit an oxidative stress,16-18 but did increase expression of GRP78 and C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP)/GADD153, both of which respond to agents or conditions that adversely affect the function of ER. In fact, homocysteine is reported to inhibit the cell-surface expression of thrombomodulin9 and processing and secretion of von Willebrand factor10 by preventing their exit from the ER. In the present study, the homocysteine-induced activation of JNK/SAPK and ATF3 expression could be mimicked by other thiol compounds and tunicamycin, a potent inducer of ER stress. It is, therefore, strongly suggested that the homocysteine effect was caused by reductive ER stress. More recently, ER stress has been shown to be coupled to activation of JNK/SAPK through an ER-residential protein kinase, IRE1.47 IRE1 is capable of activating expression of the ER chaperon GRP78/Bip, as well as non–ER-resident proteins such as the transcription factor CHOP/GADD153.48 Therefore, ATF3 might represent one of these non-ER proteins induced by ER stress. The possibility that homocysteine activates JNK/SAPK through the IRE1-dependent pathway is now under investigation.

Homocysteine has antiproliferative effects in endothelial cells.14,18,49 It reduced DNA synthesis, and this effect was specifically observed at pathophysiological concentration of homocysteine by inhibiting p21rasmethylation.49 It is not yet clear whether the JNK/SAPK activation and ATF3 expression by homocysteine are related to the antiproliferative effect. In this study, the homocysteine effect was similarly observed in both subconfluent and confluent cells (Figure4B). However, it is possible that ER stress induced by homocysteine may directly or indirectly affect the cell proliferative activity, since ER stress has been reported to induce G1 arrest and programmed cell death.50,51 More importantly, homocysteine caused the rapid and sustained activation of JNK/SAPK, while p38 activation occurred after prolonged exposure (Figure 2A). Although the significance of p38 activation is not known, sustained activation of JNK/SAPK has recently been reported to be well correlated with the induced apoptotic cell death.52-54 Since we observed that homocysteine induced cell death in endothelial cells (C.Z. and S.K, unpublished data, 2000), it is speculated that JNK/SAPK activation and ATF3 induction might represent a novel pathway and gene expression that are involved in ER-stress–induced cell death. The significance of ATF3 in this process is now under vigorous investigation.

Significant effects of homocysteine in this study occurred at far higher concentration than the pathophysiologic range of 0.05 to 0.3 mmol/L, at which small but significant effects were observed (Figures 1C and 3). We speculate that it is not the extracellular but the intracellular level of homocysteine that activates JNK/SAPK and ATF3 expression, and that cells are capable of metabolizing exogenous homocysteine through such enzymatic activities as cystathionine β-synthase and 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. In fact, significant increase of the intracellular homocysteine was observed only when HUVECs were exposed to high extracellular concentration of 5 mmol/L.17 Furthermore, endothelial cells from heterozygotes for cystathionine β-synthase deficiency are more sensitive to homocysteine toxicity.55 In our study, cysteine did not show appreciable effect, consistent with previous reports that cysteine failed to induce GRP78 mRNA17 and that a high concentration of cysteine was required to obtain an appreciable induction of GRP78.16 We speculate that endothelial cells are highly susceptible to homocysteine, which might be preferentially accumulated in cells. Alternatively, endothelial cells might be capable of metabolizing cysteine more efficiently than homocysteine. It is also possible that homocysteine might have a specific effect in addition to ER stress. The precise mechanism will be the subject of future study.

Finally, the present study demonstrated for the first time that homocysteine activates JNK/SAPK by its reductive stress and subsequently induces the transcriptional repressor ATF3 in endothelial cells. Although the functional role of ATF3 in the homocysteine-induced endothelial cell dysfunction has not been established, ATF3 might have a role in the altered gene expression involved in endothelial cell growth and proliferation. More investigations, including identification of the upstream signal from homocysteine to the activation of JNK/SAPK and the downstream target genes regulated by ATF3, will be required to clarify the significance of ATF3 induction in vascular endothelial cell dysfunction associated with homocysteinemia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Tsonwin Hai for the gift of pETATF3 and pATF3CAT; Dr Richard N. Kolesnick for dominant negative MKK4/SEK1; Dr Kinichiro Oda for expression plasmids for ATF2, ATF4, and c-Jun; and Drs Joan W. Conaway and Peter Hawkes for critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

Supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, and from National Space Development Agency of Japan and Japan Space Forum (S.K).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Shigetaka Kitajima, Department of Biochemical Genetics, Medical Research Institute, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, 1-5-45, Yushima, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, 113-8510, Japan; e-mail:kita.bgen@mri.tmd.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal