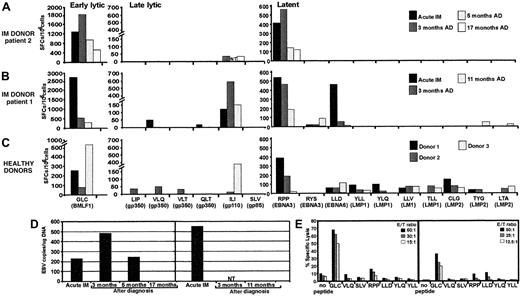

One of the intriguing and largely unexplained features of primary Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in humans is that only a small proportion of individuals display the clinical symptoms of acute infectious mononucleosis (IM).1 Previous studies have proposed a role for a number of potential factors in controlling the symptoms of primary EBV infection, such as viral load and cytokine dysregulation.2 It is entirely feasible that the dynamics of emergence of the EBV-specific T-cell response during the early stages of acute infection may delimitate the patterns of clinical symptoms in different individuals. Indeed, massive expansion of CD8+ T cells specific for EBV latent and lytic antigens, which is often a feature of acute EBV infection, suggests that these T-cell responses are recruited to control the active viral infection.1-3 However, understanding the biological significance and the longitudinal dynamics of these T cells during acute viral infections in humans is often difficult and is complicated by the nature of immune responses in naturally outbred individual patients. We have addressed some of these limitations by analyzing the dynamics of T-cell responses to a large panel of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes in 2 HLA class I–matched unrelated human subjects undergoing a primary EBV infection with contrasting clinical symptoms—patient 1's acute phase was relatively brief (2-3 weeks), and patient 2 sustained protracted symptoms (4 months). We have also included a panel of HLA-matched, unrelated healthy virus carriers, which allowed us to compare their CTL responses to the responses seen in the 2 acute IM patients. Although expansions of antigen-specific T cells were observed in both patients during the acute phase of infection, ex vivo analysis based on the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay indicated that rapid recovery from IM symptoms in patient 1 was clearly coincident with broad T-cell reactivity to multiple epitopes within lytic and latent antigens and that protracted illness in patient 2 correlated with a narrowly focused response (Figure 1A-B). A total of 7 different epitopes were targeted simultaneously in the rapidly recovering patient 1 and were presented by 3 different class I alleles. In addition, these responses persisted, albeit at low levels, for the duration of follow-up, despite a reduction in EBV load and resolution of clinical symptoms. Similar broad T-cell reactivity was consistently seen in all healthy virus carriers (Figure 1C). Thus it seems that recruitment of a T-cell response specific for multiple epitopes may be more efficient in controlling the outgrowth of EBV-infected cells and thus ensure rapid resolution of clinical symptoms. This contention is compatible with recent studies by Lechner and colleagues, who also showed that broadly directed T-cell responses were more common in individuals who had cleared hepatitis C virus compared with those with a persistent viremia.7 A comparison of the EBV DNA load in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) during the acute phase of infection indicated that patient 1 had a more than 2-fold higher EBV copy number than patient 2 (Figure 1D). The level of EBV DNA in patient 2 increased over the next 3 months and dropped significantly by 5 months. During this period the overall pattern of narrowly focused CTL responses remained unchanged, although a significant increase in the absolute number of virus-specific CTLs was observed as the DNA load increased after the primary infection. The inefficient control of active EBV infection by patient 2 was not due to a lack of cytolytic function by the antigen-specific T cells. In fact the overall strength of ex vivo cytolytic activity against the HLA A2–restricted BMLF1 epitope during the acute phase was higher in patient 2 (Figure 1E). On the other hand, additional low-level ex vivo CTL reactivity to latent antigen epitopes was detected in patient 1 by cytotoxicity assays.

Analysis of the EBV-specific CTL response and EBV DNA load in the peripheral blood of IM patients.

(A-C) Functional analysis of EBV-specific CTL responses in acute IM patients 2 (A) and 1 (B), and 3 healthy donors (C) using ELISPOT assay. PBMCs from these individuals were stimulated with peptide epitopes from early lytic, late lytic, and latent antigens, and the interferon γ response was measured in ELISPOT assays as described previously.4 The following CTL epitopes were used in this study: restricted through HLA A2—GLCTLVAML (GLC), SLVIVTTFV (SLV), ILIYNGWYA (ILI), VLQWASLAV (VLQ), VLTLLLLLV (VLT), LIPETVPYI (LIP), QLTPHTKAV (QLT), LLDFVRFMGV (LLD), YLQQNWWTL (YLQ), YLLEMLWRL (YLL), LLVDLLWLL (LLV), TLLVDLLWL (TLL), LTAGFLIFL (LTA), CLGGLLTMV (CLG); HLA B7—RPPIFIRRL (RPP); and HLA A24—RYSIFFDY (RYS), TYGPVFMCL (TYG). For acute IM patients, ELISPOT analysis was conducted during the acute phase of infection and at different time intervals after diagnosis (AD). The results are expressed as spot-forming cells (SFCs) per 106 PBMCs. NT indicates not tested. (D) EBV DNA load in the peripheral blood of IM patients 2 (left) and 1 (right) at diagnosis and after diagnosis. EBV DNA load was measured as described elsewhere.5 (E) EBV epitope–specific ex vivo cytotoxic T-cell activity in peripheral blood lymphocytes from IM donors using peptide-sensitized (1 μg/mL) phytohemagglutinin blasts as targets. Peptide epitopes used in these assays are shown on the x-axis. Results are expressed as percent specific lysis. E/T ratio indicates effector-target ratio.

Analysis of the EBV-specific CTL response and EBV DNA load in the peripheral blood of IM patients.

(A-C) Functional analysis of EBV-specific CTL responses in acute IM patients 2 (A) and 1 (B), and 3 healthy donors (C) using ELISPOT assay. PBMCs from these individuals were stimulated with peptide epitopes from early lytic, late lytic, and latent antigens, and the interferon γ response was measured in ELISPOT assays as described previously.4 The following CTL epitopes were used in this study: restricted through HLA A2—GLCTLVAML (GLC), SLVIVTTFV (SLV), ILIYNGWYA (ILI), VLQWASLAV (VLQ), VLTLLLLLV (VLT), LIPETVPYI (LIP), QLTPHTKAV (QLT), LLDFVRFMGV (LLD), YLQQNWWTL (YLQ), YLLEMLWRL (YLL), LLVDLLWLL (LLV), TLLVDLLWL (TLL), LTAGFLIFL (LTA), CLGGLLTMV (CLG); HLA B7—RPPIFIRRL (RPP); and HLA A24—RYSIFFDY (RYS), TYGPVFMCL (TYG). For acute IM patients, ELISPOT analysis was conducted during the acute phase of infection and at different time intervals after diagnosis (AD). The results are expressed as spot-forming cells (SFCs) per 106 PBMCs. NT indicates not tested. (D) EBV DNA load in the peripheral blood of IM patients 2 (left) and 1 (right) at diagnosis and after diagnosis. EBV DNA load was measured as described elsewhere.5 (E) EBV epitope–specific ex vivo cytotoxic T-cell activity in peripheral blood lymphocytes from IM donors using peptide-sensitized (1 μg/mL) phytohemagglutinin blasts as targets. Peptide epitopes used in these assays are shown on the x-axis. Results are expressed as percent specific lysis. E/T ratio indicates effector-target ratio.

Further characterization of the EBV-specific CTL responses with HLA-peptide tetramers revealed interesting dynamics during the course of acute IM with respect to the absolute numbers and the phenotypic markers expressed by the antigen-specific T cells. Consistent with the ELISPOT assays, ex vivo staining with HLA-peptide tetramers also showed that a large proportion of CD8+ T cells were specific for an early lytic antigen during the acute phase of infection, which was followed by a significant culling during the recovery phase (Table1). One of the most surprising aspects of these results was the apparent discrepancy in the number of early lytic and latent antigen–specific T cells detected by tetramer staining and its relationship to clinical symptoms. Tetramer staining showed that the proportion of CD8+ T cells specific for both a lytic and a latent antigen was 2- to 3-fold higher during the acute phase in patient 2 compared to patient 1. Although the overall number of antigen-specific T cells dropped significantly as this patient recovered from acute IM, the number of tetramer-positive, early lytic antigen–specific T cells was still maintained at much higher levels when compared to the rapidly recovered patient 1.

Ex vivo enumeration and phenotypic analysis of EBV-specific CTLs using major histocompatibility complex–peptide tetramers

| Donor code . | CD8 and tetramer* (% positive) . | CD27† (% positive/negative) . | CD38† (% positive/negative) . | CD44† (% positive/negative) . | CD62L† (% positive/negative) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLC . | RPP . | GLC . | RPP . | GLC . | RPP . | GLC . | RPP . | GLC . | RPP . | |

| Patient 1 acute IM | 2.40 | 0.23 | 87/13 | 80/20 | 100/0 | 100/0 | 100/0 | 100/0 | 47/53 | 44/56 |

| After IM (11 mo) | 0.26 | 0.27 | 35/65 | 43/57 | 65/35 | 58/42 | 96/4 | 100/0 | 37/63 | 37/63 |

| Patient 2 acute IM | 4.40 | 0.61 | 63/37 | 63/37 | 76/24 | 87/13 | 96/4 | 93/7 | 21/79 | 35/65 |

| After IM (5 mo) | 0.72 | 0.41 | 33/67 | 32/68 | 68/32 | 70/30 | 94/6 | 100/0 | 50/50 | 47/53 |

| After IM (17 mo) | 1.14 | 0.23 | 41/59 | 28/72 | 63/37 | 37/63 | 96/4 | 86/14 | 17/83 | 10/90 |

| Donor 3 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 25/75 | 12/88 | 46/54 | 44/56 | 100/0 | 100/0 | 18/82 | 0/100 |

| Donor code . | CD8 and tetramer* (% positive) . | CD27† (% positive/negative) . | CD38† (% positive/negative) . | CD44† (% positive/negative) . | CD62L† (% positive/negative) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLC . | RPP . | GLC . | RPP . | GLC . | RPP . | GLC . | RPP . | GLC . | RPP . | |

| Patient 1 acute IM | 2.40 | 0.23 | 87/13 | 80/20 | 100/0 | 100/0 | 100/0 | 100/0 | 47/53 | 44/56 |

| After IM (11 mo) | 0.26 | 0.27 | 35/65 | 43/57 | 65/35 | 58/42 | 96/4 | 100/0 | 37/63 | 37/63 |

| Patient 2 acute IM | 4.40 | 0.61 | 63/37 | 63/37 | 76/24 | 87/13 | 96/4 | 93/7 | 21/79 | 35/65 |

| After IM (5 mo) | 0.72 | 0.41 | 33/67 | 32/68 | 68/32 | 70/30 | 94/6 | 100/0 | 50/50 | 47/53 |

| After IM (17 mo) | 1.14 | 0.23 | 41/59 | 28/72 | 63/37 | 37/63 | 96/4 | 86/14 | 17/83 | 10/90 |

| Donor 3 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 25/75 | 12/88 | 46/54 | 44/56 | 100/0 | 100/0 | 18/82 | 0/100 |

PBMCs from IM patients 1 and 2 and healthy donor 3 were costained with anti–human CD8− tricolor-labeled antibody and phycoerythrin-labeled HLA A2/GLC or HLA B7/RPP tetramers. Fluorescence intensities were then measured with a FACScan. Values indicate the percent CD8 T cells positive for HLA A2/GLC or HLA B7/RPP tetramer.

For phenotypic analysis PBMCs from these individuals were costained with HLA-peptide tetramers for early lytic (GLC) or latent (RPP) epitopes and monoclonal antibodies specific to T-cell surface antigens (CD27, CD38, CD44, or CD62L). Values shown indicate the percent HLA-peptide tetramer–reactive T cells positive/negative for CD27, CD38, CD44, or CD62L.

Significant phenotypic heterogeneity within antigen-specific T-cell populations was observed between the 2 patients, perhaps reflecting differences in the clinical symptoms and the duration of antigen exposure. A very high proportion (80%-100%) of both lytic and latent antigen–specific T cells from patient 1 during the acute phase of infection had an activated/memory phenotype with high levels of expression of CD38, CD44, and CD27. On the other hand, a much lower proportion (∼60%) of antigen-specific T cells in patient 2 were positive for CD27. Similar heterogeneity in the expression of CD62L on antigen-specific T cells was observed during the acute phase. As the symptoms of acute infection resolved in both patients, the majority of antigen-specific T cells differentiated as effector/memory T cells (CD27- and CD62L-negative phenotype). Surprisingly, both acute IM patients continued to maintain a high proportion of T cells with an activated phenotype (CD38 positive) even after the resolution of acute infection, indicating continuing exposure to the viral antigens either in the lymph nodes or at other sites where the virus establishes its long-term latent infection.

This study is the first to demonstrate directly that a broadly directed CTL response with strong functional activity was coincident with the resolution of acute EBV infection. This conclusion is strongly supported by previous studies on animal models of hepatitis C virus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection, which have shown that the breadth of the CTL response may be important in maintaining viral control.6-8 Overall the present study provides an important platform for future investigations on a larger cohort of patients, particularly those undergoing chronic active EBV infection, to determine if a narrowly focused T-cell repertoire with limited functional activity contributes to the protracted illness.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal