The t(10;11)(p12;q23) chromosomal translocation in human acute myeloid leukemia results in the fusion of theMLL and AF10 genes. The latter codes for a novel leucine zipper protein, one of many MLL fusion partners of unknown function. In this report, we demonstrate that retroviral-mediated transduction of an MLL-AF10complementary DNA into primary murine myeloid progenitors enhanced their clonogenic potential in serial replating assays and led to their efficient immortalization at a primitive stage of myeloid differentiation. Furthermore, MLL-AF10–transduced cells rapidly induced acute myeloid leukemia in syngeneic or severe combined immunodeficiency recipient mice. Structure/function analysis showed that a highly conserved 82–amino acid portion of AF10, comprising 2 adjacent α-helical domains, was sufficient for immortalizing activity when fused to MLL. Neither helical domain alone mediated immortalization, and deletion of the 29–amino acid leucine zipper within this region completely abrogated transforming activity. Similarly, the minimal oncogenic domain of AF10 exhibited transcriptional activation properties when fused to the MLL or GAL4 DNA-binding domains, while neither helical domain alone did. However, transcriptional activation per se was not sufficient because a second activation domain of AF10 was neither required nor competent for transformation. The requirement for α-helical transcriptional effector domains is similar to the oncogenic contributions of unrelated MLL partners ENL and ELL, suggesting a general mechanism of myeloid leukemogenesis by a subset of MLL fusion proteins, possibly through specific recruitment of the transcriptional machinery.

Introduction

Chromosomal translocations involving theMLL (HRX, ALL1, hTRX) gene at 11q23 produce a diverse array of fusion proteins that are associated with high-risk acute myeloid and lymphoid leukemias.1 The MLL protein is required for normal hematopoiesis and has been implicated as an upstream regulator of Hoxgenes.2-4 Increasing evidence supports a gain-of-function mechanism for leukemic transformation by MLL fusion proteins.5,6 However, alternative mechanisms have been proposed.7 8 Thus, defining the contributions of MLL fusion partners to the oncogenic activation of MLL is important for understanding the molecular pathogenetic roles for MLL chimeric proteins in a clinically aggressive subset of hematologic malignancies.

More than 30 MLL fusion partners have been reported to date.1 Most of these are novel proteins of unknown function that display structural heterogeneity. Thus, no common theme has emerged to account for their oncogenic roles in activating the leukemogenic properties of MLL. Some of the most frequent MLL partners, AF-4 (FEL), ENL, and ELL, display an ability to activate transcription under experimental conditions.9-12 For ENL and ELL, domains with transcriptional effector properties coincide with regions that are necessary and sufficient, when fused to MLL, for transformation of murine myeloid progenitors by their respective MLL chimeras.12,13 The less common partners CBP and p300 are also implicated in transcriptional regulation.14,15Recently, both the bromo and histone acetyltransferase domains of CBP were shown to be required for transformation by MLL-CBP.16

A third group of MLL fusion partners, including AF10, contains sequence motifs common to transcription factors but has not been shown to regulate transcription. AF10 was discovered by virtue of its involvement in t(10;11)(p12;q23) chromosomal translocations that occur primarily in acute myeloid leukemias.17 This genetic rearrangement fuses the carboxy-terminal portions of AF10 to the amino-terminal third of MLL. The minimal portion of AF10 fused to MLL contains a leucine zipper (LZ) motif embedded within a region of 82 amino acids that is highly conserved between the human,Drosophila, and Caenorhabditis elegans homologs. We demonstrate here that MLL-AF10 immortalizes myeloid progenitors in vitro and is rapidly leukemogenic in vivo. The conserved region spanning and flanking the LZ of AF10 is required for immortalization of murine myeloid progenitors and also possesses transcriptional activation potential. These studies suggest that the ability to recruit the transcriptional machinery may be a unifying mechanism for the contributions of a subset of MLL fusion partners to leukemogenesis.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructs

A general purpose murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviral vector (MSCV-5′MLL) containing MLL sequences encoding amino acids 1 to 1395 was constructed from the MSCV-HRX/ENLplasmid.6 Following digestion with PflMI andXhoI, ENL sequences flanked by these restriction sites were replaced by a synthetic oligonucleotide containing NruI,PmlI, and HpaI sites followed by stop codons in all 3 translational reading frames. MSCV-MLL/AF10 was constructed by inserting a BglII-XbaI fragment (encoding amino acids 682-1085) of AF10 into the NruI site of MSCV-5′MLL. Deletion mutants of AF10 were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification usingAF10 complementary DNA (cDNA) as template and synthetic oligonucleotide primers whose sequences are available upon request. PCR products were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes and subcloned into the multicloning site of MSCV-5′MLL. For expression studies, the same fragments were subcloned into the pCMV5 vector. MSCV-FLAG/AF10 was constructed by subcloning a fragment of AF10 (encoding amino acids 682-1085) in-frame downstream of a FLAG epitope tag in Bluescript (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). An EcoRI-XhoI fragment encoding the amino-terminal epitope tag and AF10 sequence was inserted into the EcoRI-XhoI site of MSCVneo. The nucleotide sequences of all constructs were determined. PGL-3-HoxA7 (a gift from Dr R. Slany, Lehrsiuhl Genetik Universitat, Erlangen, Germany) was constructed as described previously.18 GAL4-AF10 fusion cDNAs were constructed by subcloning AF10 DNA fragments or PCR products identical to those used to generate MLL fusion genes into the pSG424 vector.19 The G4-TKluc reporter vector was constructed by replacing the SV40 promoter sequences in pGL3 basic (Promega, Madison, WI) with a fragment from G4-TKCAT11 containing 3 tandem copies of the GAL4 UAS upstream of the thymidine kinase promoter.

Myeloid transformation assays

Transduction of murine bone marrow (BM) cells was performed essentially as described previously6 with minor modifications. Briefly, 4-week-old C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously (tail vein) with 5-flurouracil (150 mg/kg), and BM cells were harvested from both femurs 5 days later. Retroviral supernatants were produced by transient transfection of φNX packaging cells with MSCV constructs.20 Retroviral titers ranged from 0.2 × 105 to 1 × 105/mL as determined by infection of NIH3T3 cells followed by selection in G418. BM cells were infected with recombinant virus by spinoculation at 2500 rpm for 2 hours at 32°C. Transduced cells were plated in 0.9% methylcellulose (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) supplemented with 20 ng/mL SCF; 10 ng/mL each of interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-6, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN); and 1 μg/mL G418. After 7 to 10 days, colonies were counted, pooled, and single-cell suspensions of 104 cells were replated in methylcellulose cultures without G418. For liquid cultures, cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented withl-glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin, 20% fetal calf serum, and 20% WEHI-conditioned media as a source of IL-3.

Cell surface phenotype analysis

Flow cytometry was performed on cultured cells or cell suspensions from spleen, liver, or BM of leukemic mice. Cells were stained with phycoerythrin- and fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated isotype controls and monoclonal antibodies for Gr-1, Mac-1, c-Kit, and other markers (Pharmingen, San Diego CA). Stained cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Beckton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

RT-PCR and Southern blotting

Total RNA was prepared from culturedMLL-AF10–transduced BM cells using Trizol (Gibco) and reverse transcribed using an oligonucleotide primer (5′-ACAGCTCGAGAATTAATCAGGTAAAAAGCT-3′), SuperScript reverse transcriptase, and commercially prepared reagents (Gibco). Reverse transcription products were amplified using specific primers (sequences available on request) and Taq polymerase for 20 cycles. For Southern blots, genomic DNA was isolated from the HA.1 cell line and from spleens or livers of leukemic mice by standard techniques. DNAs were digested with EcoRI, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and hybridized with a Neo-specific radiolabeled probe using standard procedures.

Murine tumor challenge experiments

Four-week-old nonirradiated C57BL/6 or severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice were injected intravenously (tail vein) with 106MLL-AF10–transduced BM cells from first- or second-passage liquid cultures initiated from third-round methylcellulose colonies. Mice were observed on a daily basis for the onset of symptoms and euthanized when moribund. Blood for analysis was obtained by tail bleedings or cardiac puncture of euthanized mice. White blood cell counts were performed manually using Turk solution and a hemocytometer. Tissue samples were decalcified (bone), fixed in buffered formalin, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard techniques.

Western blotting

COS7 cells transiently transfected with each construct were harvested from 6-well plates and lysed in 250 μL 1 × sample buffer.21 Proteins from approximately 10 μL lysate were fractionated by electrophoresis through 6% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (BioRad, Richmond, CA) using Tris glycine sodium dodecyl sulfate transfer buffer. After blocking with 5% milk, membranes were probed with monoclonal antibody N4.4 directed against an MLL amino-terminal epitope.

Transcriptional assays

Four micrograms of pGL3-HoxA7 were cotransfected with 4 μg MSCV-5′MLL or the indicated MLL fusion cDNA and 2 μg pCMVsportβgal (Gibco) into 293T cells by calcium phosphate precipitation. Alternatively, 4 μg pG4-TKluc reporter were cotransfected with 4 μg GAL4 fusion construct and 2 μg β-galactosidase plasmid. After 48 hours, equivalent amounts of each lysate were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity using commercially prepared reagents (Promega; Tropix, Bedford, MA) and a Monolight 2010 luminometer. Relative light units from duplicate luciferase assays were corrected for transfection efficiency using relative light units from their respective β-galactosidase controls.

Results

MLL-AF10 immortalizes primary murine myeloid progenitors in vitro

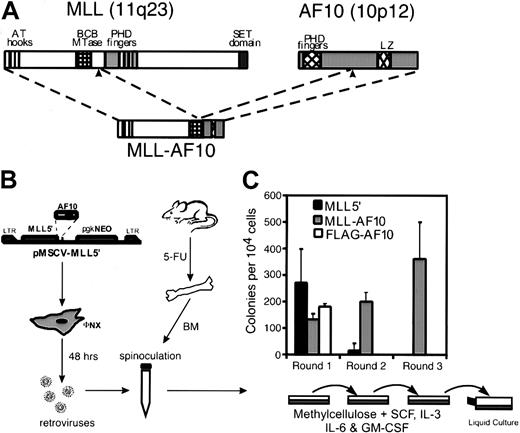

A methylcellulose serial replating assay6 was used to assess the effects of MLL-AF10 on the in vitro growth properties of murine myeloid progenitors (Figure 1). The MSCV was employed to transduce freshly harvested BM cells from mice treated 5 days previously with 5-flurouracil. MSCV constructs encoded either MLL-AF10, MLL sequences 5′ of the translocation breakpoint (MLL5′), or AF10 amino acids 682 to 1085 with an amino-terminal FLAG tag (FLAG-AF10). Retroviral transduction efficiency, determined for each construct by plating transduced BM cells under selective (G418) and nonselective conditions, ranged from 40% to 60% in various experiments (not shown). Western blotting of extracts from transiently transfected retroviral packaging cells confirmed that the MLL5′ and FLAG-AF10 constructs were efficiently expressed (not shown). Plating of cells transduced with the 3 MSCV constructs under selective conditions showed similar numbers, size, and morphology of myeloid colonies after 7 days in primary methylcellulose cultures (Figure 1B and data not shown). However, significant differences were observed in a second round of plating initiated by 104 cells pooled from colonies harvested from first-round cultures.MLL-AF10–transduced cells gave rise to hundreds of colonies in second- (and third-) round platings, while cells fromMLL5′- or FLAG-AF10–transduced cultures produced few or no secondary colonies (Figure 1B). In addition, single-cell suspensions from second- and third-round cultures were readily adapted to growth in liquid media supplemented with IL-3 and have been maintained in continuous culture for several months. Withdrawal of IL-3 from these liquid cultures resulted in loss of proliferative capacity. Therefore, expression of MLL-AF10 in primary BM cells led to the immortalization of clonogenic, IL-3–dependent hematopoietic progenitors.

Retroviral transduction of MLL-AF10enhances the in vitro replating potential of primary murine BM cells.

(A) Diagrammatic representations of the MLL and AF10 proteins are shown with known structural motifs indicated. Translocation t(10;11)(p12;q23) joins the amino-terminal portion of MLL to the carboxy-terminal portion of AF10 containing its LZ motif. (B) Schematic representation of the retroviral transduction protocol. (C) Colonies generated per 104 transduced BM cells were determined in first-, second-, and third-round cultures for MLL5′,MLL-AF10, and FLAG-AF10 constructs. First-round results indicate G418R colonies. Bars represent the mean ± SD for 3 experiments.

Retroviral transduction of MLL-AF10enhances the in vitro replating potential of primary murine BM cells.

(A) Diagrammatic representations of the MLL and AF10 proteins are shown with known structural motifs indicated. Translocation t(10;11)(p12;q23) joins the amino-terminal portion of MLL to the carboxy-terminal portion of AF10 containing its LZ motif. (B) Schematic representation of the retroviral transduction protocol. (C) Colonies generated per 104 transduced BM cells were determined in first-, second-, and third-round cultures for MLL5′,MLL-AF10, and FLAG-AF10 constructs. First-round results indicate G418R colonies. Bars represent the mean ± SD for 3 experiments.

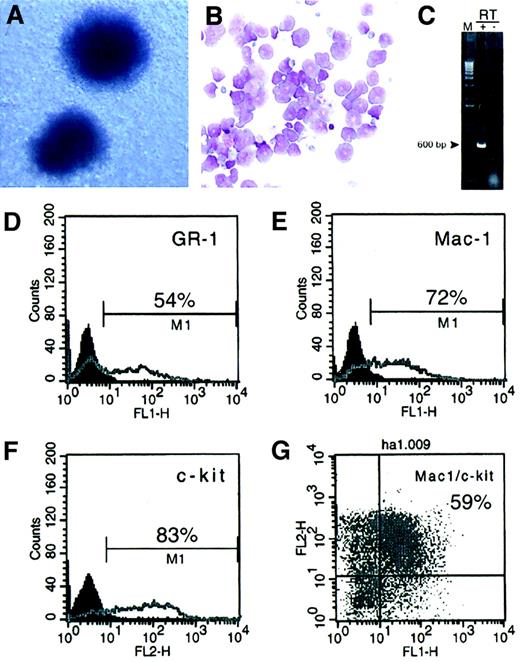

The colonies arising in second- and third-round platings ofMLL-AF10–transduced BM cells exhibited round, compact morphology consistent with early granulocyte/monocyte lineage (Figure2A). May-Grünwald/Giemsa–stained cytospin preparations of cells comprising these colonies showed features consistent with varying degrees of myeloid maturation ranging from myeloblastic forms to rare dysplastic granulocytes (Figure 2B). Immunophenotyping of cells in early liquid cultures revealed that the majority expressed the early myeloid markers Mac-1 and c-Kit and low-level expression of Gr-1 (Figure 2D-G). None of the cells expressed markers indicative of lymphoid (B220, CD3) or erythroid (Ter119) differentiation (not shown). As has been found for murine cells immortalized by other MLL fusion proteins, expression of the oncoprotein was undetectable by Western blotting. Reverse transcriptase–mediated (RT)-PCR analysis of RNA from immortalized cells, however, confirmed that they expressed the MLL-AF10fusion transcript (Figure 2C). These data indicated that BM cells immortalized by MLL-AF10 were arrested at a relatively early stage of myeloid differentiation.

MLL-AF10 immortalizes murine myeloid progenitors.

(A) Morphology of colonies formed in methylcellulose byMLL-AF10–transduced cells (May-Grünwald/Giemsa stain, × 10). (B) May-Grünwald/Giemsa–stained cytospin preparation shows cells with a range of primitive myeloid morphology (× 50). (C) RT-PCR analysis shows the presence ofMLL-AF10 transcripts in immortalized cells. (D-G) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis ofMLL-AF10–transduced cells was performed after third-round cultures. Percent of cells expressing the indicated surface antigens is indicated.

MLL-AF10 immortalizes murine myeloid progenitors.

(A) Morphology of colonies formed in methylcellulose byMLL-AF10–transduced cells (May-Grünwald/Giemsa stain, × 10). (B) May-Grünwald/Giemsa–stained cytospin preparation shows cells with a range of primitive myeloid morphology (× 50). (C) RT-PCR analysis shows the presence ofMLL-AF10 transcripts in immortalized cells. (D-G) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis ofMLL-AF10–transduced cells was performed after third-round cultures. Percent of cells expressing the indicated surface antigens is indicated.

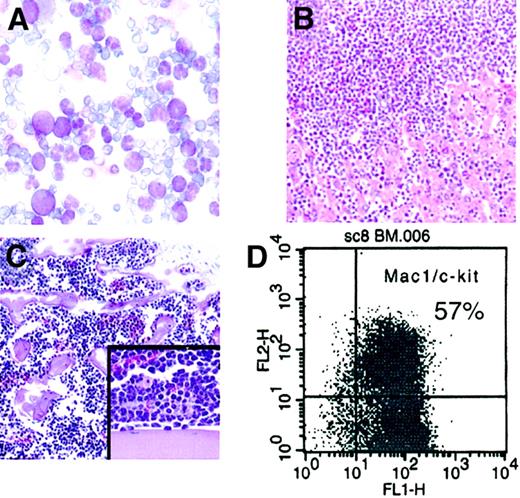

MLL-AF10–transduced cells induce myeloid leukemias

The leukemogenic potential of cells immortalized byMLL-AF10 was evaluated following transplantation into nonirradiated syngeneic (C57BL/6) or SCID mice. Following injection with 106MLL-AF10–transduced cells from early-passage liquid cultures, all mice died or developed symptoms of illness within 100 days (Table 1). The latency period was shorter for SCID recipients than for immunocompetent syngeneic mice. Analysis of the peripheral blood from moribund mice revealed dramatic hyperleukocytosis (Table 1 and Figure3A) with circulating myeloblasts. In addition, the BM was effaced by a monotonous population of mononuclear cells (Figure 3B). All injected mice exhibited significant hepatosplenomegaly, and histologic examination showed that the liver and spleen were extensively infiltrated by blasts (Figure 3C and not shown). Flow cytometric analysis of these tissues revealed the presence of a population of cells coexpressing Mac-1 and c-Kit (Figure 3D). Identical, clonal configurations of intact proviral genomes were detected in the leukemic blasts and the cultured cells (HA.1) prior to injection (data not shown). These studies demonstrated that cells immortalized in vitro by MLL-AF10 are leukemogenic with short latencies in syngeneic hosts.

Characteristics of leukemias induced byMLL-AF10

| Mouse . | Strain . | Latency, d . | White blood cells, × 109/L . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCID | 57 | nd |

| 2 | SCID | 57 | nd |

| 3 | SCID | 60 | 93 |

| 4 | SCID | 59 | 193 |

| 5 | SCID | 64 | 152 |

| 6 | SCID | 63 | 678 |

| 7 | SCID | 58 | nd |

| 8 | SCID | 59 | 506 |

| 9 | SCID | 63 | 698 |

| 10 | SCID | 64 | 162 |

| 11 | C57BL/6 | 71 | 57 |

| 12 | C57BL/6 | 99 | 27 |

| 13 | C57BL/6 | 94 | nd |

| Mouse . | Strain . | Latency, d . | White blood cells, × 109/L . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCID | 57 | nd |

| 2 | SCID | 57 | nd |

| 3 | SCID | 60 | 93 |

| 4 | SCID | 59 | 193 |

| 5 | SCID | 64 | 152 |

| 6 | SCID | 63 | 678 |

| 7 | SCID | 58 | nd |

| 8 | SCID | 59 | 506 |

| 9 | SCID | 63 | 698 |

| 10 | SCID | 64 | 162 |

| 11 | C57BL/6 | 71 | 57 |

| 12 | C57BL/6 | 99 | 27 |

| 13 | C57BL/6 | 94 | nd |

nd indicates not determined.

MLL-AF10immortalized cells are leukemogenic.

(A) May-Grünwald/Giemsa–stained cells from peripheral blood show hyperleukocytosis with myeloblasts (× 50). (B) BM aspirate shows monotonous population of mononuclear cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 10). (C) Liver displays extensive infiltration by blasts (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 10; insert, × 20). (D) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of leukemia cells shows that most cells coexpress the surface antigens Mac1 and c-kit.

MLL-AF10immortalized cells are leukemogenic.

(A) May-Grünwald/Giemsa–stained cells from peripheral blood show hyperleukocytosis with myeloblasts (× 50). (B) BM aspirate shows monotonous population of mononuclear cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 10). (C) Liver displays extensive infiltration by blasts (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 10; insert, × 20). (D) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of leukemia cells shows that most cells coexpress the surface antigens Mac1 and c-kit.

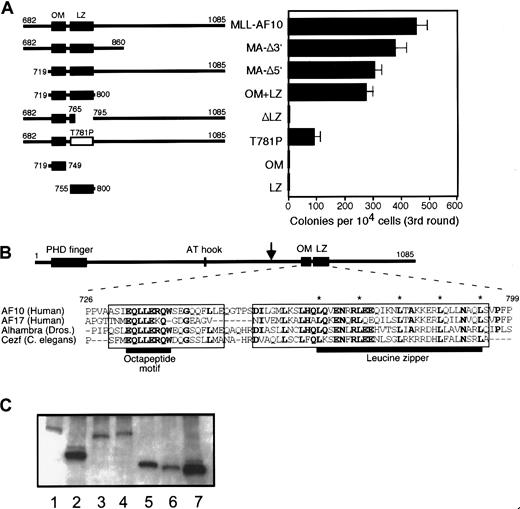

Two adjacent, conserved α-helical motifs of AF10 are necessary and sufficient for immortalization by MLL-AF10

The inability of MLL5′ to immortalize myeloid progenitors (Figure 1B) suggested that portions of AF10 were required for the transforming activity of MLL-AF10. To investigate this requirement, various deletion mutants of MLL-AF10 were tested for their ability to immortalize myeloid progenitors in vitro. Deletion of sequences encoding AF10 amino acids 682 to 718 (MA-Δ5′) or 861 to 1085 (MA-Δ3′) had no significant effect on the ability of MLL-AF10 to enhance the clonogenic potential of primary BM cells (Figure4A). Both of these deletions spared an 82–amino acid region of AF10 containing 2 sequences that are highly conserved in AF10-related proteins from Drosophila andC elegans. These homology regions include an almost perfectly conserved octapeptide (EQLLERQW) motif (OM) separated by a short nonconserved sequence from a classical LZ (Figure 4B). Secondary structure modeling of these sequences strongly predicts 2 distinct α-helical domains separated by a nonhelical segment.21

Two helical domains of AF10 are necessary and sufficient for immortalization of myeloid progenitors by MLL-AF10.

(A) Schematic illustrations of AF10 sequences fused to MLL5′ are shown in the left panel. Amino acid numbering is based on that of wild-type AF10.35 The OM and LZ are indicated by filled boxes. Open box denotes LZ containing a site-directed missense T781P mutation. In the right panel, horizontal bars represent the number of colonies generated per 104 cells plated in third-round cultures. Bars represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from a representative experiment. (B) Amino acid sequences of the OM and LZ of AF10 are conserved in orthologous proteins from Drosophilaand C elegans. Identical amino acids in 3 or more sequences are shown in bold. Asterisks indicate conserved heptad repeat leucine residues. Boxes indicate domains that have predicted α-helical secondary structures. Black horizontal bars denote OM and LZ, respectively. Downward arrow in AF10 schematic denotes most 3′ site of fusion with MLL in human acute myeloid leukemias. (C) Western blotting of whole cell extracts of transiently transfected COS7 cells. Lane 1, MLL-AF10; lane 2, MLL-OM+LZ; lane 3, MLL-ΔLZ; lane 4, MLL-T781P; lane 5, MLL-OM; lane 6, MLL-LZ; lane 7, MLL5′.

Two helical domains of AF10 are necessary and sufficient for immortalization of myeloid progenitors by MLL-AF10.

(A) Schematic illustrations of AF10 sequences fused to MLL5′ are shown in the left panel. Amino acid numbering is based on that of wild-type AF10.35 The OM and LZ are indicated by filled boxes. Open box denotes LZ containing a site-directed missense T781P mutation. In the right panel, horizontal bars represent the number of colonies generated per 104 cells plated in third-round cultures. Bars represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples from a representative experiment. (B) Amino acid sequences of the OM and LZ of AF10 are conserved in orthologous proteins from Drosophilaand C elegans. Identical amino acids in 3 or more sequences are shown in bold. Asterisks indicate conserved heptad repeat leucine residues. Boxes indicate domains that have predicted α-helical secondary structures. Black horizontal bars denote OM and LZ, respectively. Downward arrow in AF10 schematic denotes most 3′ site of fusion with MLL in human acute myeloid leukemias. (C) Western blotting of whole cell extracts of transiently transfected COS7 cells. Lane 1, MLL-AF10; lane 2, MLL-OM+LZ; lane 3, MLL-ΔLZ; lane 4, MLL-T781P; lane 5, MLL-OM; lane 6, MLL-LZ; lane 7, MLL5′.

A minimal portion of AF10 encoding amino acids 719 to 800 spanning the OM and LZ homology regions (OM+LZ) fused to MLL5′ was sufficient for immortalization. To determine whether one or both putative domains were essential for this function, AF10 sequences encoding each region were fused to MLL5′. Neither the OM nor the LZ motif alone was able to confer immortalizing activity to MLL5′, suggesting that both putative helices were required. Furthermore, constructs with deletion (ΔLZ) or site-directed, helix-breaking (T781P) mutations in the LZ resulted in complete or partial abrogation of transformation, respectively. Transduction efficiencies for all of these constructs were equivalent, ranging from 40% to 60% in first-round cultures (not shown). Moreover, nonimmortalizing constructs were expressed at least as efficiently as active constructs by Western blot (Figure 4C). Cells from third-round colonies were maintained in liquid culture for at least 2 months, indicating that they had been immortalized. These results showed that the adjacent OM and LZ motifs were necessary and sufficient for the oncogenic activity of MLL-AF10.

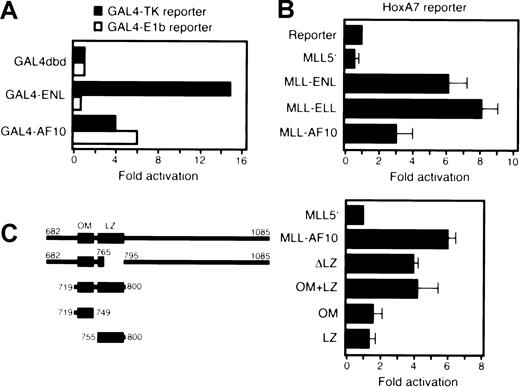

The domains of AF10 required for myeloid transformation also display transcriptional activation potential

Previous studies have shown that the leukemogenic contributions of 2 MLL fusion partners, ENL and ELL, are critically dependent on domains that possess transcriptional activation potential.12,13 To determine whether AF10 might also exhibit transcriptional activation properties, we tested its ability to stimulate expression of a luciferase reporter under the control of the GAL4 UAS and TK promoter (pG4-TKluc). A construct containing amino acids 682 to 1085 of AF10 fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain activated transcription of the reporter gene in Raji (Figure5A) and U937 (not shown) cells but at lower levels than GAL4-ENL. AF10 also activated a reporter under control of the E1b promoter unlike ENL, which displays promoter-specific activation (Figure 5A).11 In transient transfections of 293T cells, the MLL-AF10 fusion protein activated transcription of a luciferase reporter gene under the control ofHoxA7 upstream sequences (Figure 5B). The 82–amino acid OM+LZ fragment of AF10 was also able to activate transcription when fused to MLL (Figure 5C), whereas neither the OM nor the LZ domain alone conferred transcriptional activation potential to MLL5′. Deletion of the LZ (in construct ΔLZ) reduced but did not completely abrogate transcriptional activation, suggesting the presence of additional sequences in AF10 with activation potential in this assay. Nevertheless, colocalization of immortalization and transactivation domains within a highly conserved region of AF10 suggests that aberrant transcriptional regulation by MLL-AF10 is critical for its leukemogenic properties.

AF10 transforming regions activate transcription when fused to GAL4 or MLL DNA-binding domains.

(A) A luciferase reporter gene containing GAL4 binding sites upstream of a thymidine kinase or E1b promoter was cotransfected into Raji cells with expression constructs encoding GAL4 fusions of ENL or AF10. Luciferase activity was corrected for transfection efficiency based on the activity of a cotransfected β-galactosidase expression construct. The transcriptional activating potential for each fusion construct is expressed as the fold induction relative to GAL4 DNA-binding domain alone. (B) A luciferase reporter gene under control of HoxA7 upstream sequences (pGL3-HoxA7) was cotransfected into 293T cells with expression constructs encodingMLL5′ or various MLL fusion cDNAs. Data were corrected for transfection efficiencies as described above and normalized to protein levels. Bars represent the mean and SD of 3 replicates. (C) The transcriptional activation properties of various mutant MLL-AF10 fusion cDNAs (shown schematically on the left) were determined using transient cotransfection conditions identical to those described in panel B.

AF10 transforming regions activate transcription when fused to GAL4 or MLL DNA-binding domains.

(A) A luciferase reporter gene containing GAL4 binding sites upstream of a thymidine kinase or E1b promoter was cotransfected into Raji cells with expression constructs encoding GAL4 fusions of ENL or AF10. Luciferase activity was corrected for transfection efficiency based on the activity of a cotransfected β-galactosidase expression construct. The transcriptional activating potential for each fusion construct is expressed as the fold induction relative to GAL4 DNA-binding domain alone. (B) A luciferase reporter gene under control of HoxA7 upstream sequences (pGL3-HoxA7) was cotransfected into 293T cells with expression constructs encodingMLL5′ or various MLL fusion cDNAs. Data were corrected for transfection efficiencies as described above and normalized to protein levels. Bars represent the mean and SD of 3 replicates. (C) The transcriptional activation properties of various mutant MLL-AF10 fusion cDNAs (shown schematically on the left) were determined using transient cotransfection conditions identical to those described in panel B.

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate that MLL-AF10 transforms primitive myeloid progenitors when transduced into primary murine BM cells. In particular, expression of this fusion protein leads to the enhanced self-renewal of clonogenic c-Kit+/Mac-1+ progenitors that are leukemogenic in syngeneic recipients. The 60- to 100-day latency of experimental MLL-AF10 leukemia suggests that few secondary events are required for leukemogenicity. The short latency is comparable to leukemias induced by MLL-ENL6 but contrasts with the long latencies observed for MLL-CBP and MLL-ELL,16 suggesting that MLL fusion proteins may define 2 distinct groups based on leukemogenic potency.22 Furthermore, the MLL-AF10 disease recapitulates many aspects of human leukemia with MLL translocations, including hyperleukocytosis and extensive tissue infiltration by blasts.1 Thus, the enhanced in vitro replating efficiency conferred by MLL-AF10 may reflect not only early events in myeloid leukemogenesis but also factors affecting the proliferation, latency, and extramedullary invasiveness of transformed blasts.

MLL-AF10 transforms myeloid progenitors through a gain-of-function mechanism. As evidence for this, neither MLL5′ nor AF10 alone were able to immortalize myeloid progenitors, indicating that AF10 requires fusion to amino-terminal MLL sequences for efficient transformation. The portion of MLL that is joined to AF10 and other fusion partners contains nuclear localization sequences, which mediate the colocalization of MLL fusion proteins with native MLL.23,24-26 AT-hook and DNA methyltransferaselike domains in this region of MLL have also been shown to possess nonclassical DNA-binding activity,13,27 suggesting that fusion proteins have the potential to be recruited to the same genomic loci as MLL. The inability of MLL5′ to enhance self-renewal of myeloid progenitors does not appear to be a consequence of reduced protein stability because this truncated fragment of MLL is expressed at extremely high levels in transfected cells (Figure 4C).12The inability of MLL5′ to affect myeloid progenitor self-renewal in vitro is consistent with previous observations that a similar amino-terminal portion of MLL with a myc epitope tag at its carboxy-terminus was not leukemogenic in a knock-in mouse model.5 In contrast, an experimental MLL-lacZ fusion gene has been shown to produce leukemia with long latency as a knock-in allele.8 The oncogenic contributions of β-galactosidase, which is not an MLL fusion partner in human leukemias, are not clear, although it is unlikely to involve simple stabilization of MLL5′ given our observations that the latter is not oncogenic in vitro despite its high level expression.12 Thus, MLL fusion partners, including β-galactosidase, appear to confer a gain-of-function on MLL5′.

Our structure/function analyses demonstrate that the oncogenic contribution of AF10 consists of 2 conserved structural motifs with transcriptional effector properties. MLL-AF10 possesses transactivation potential as measured by transient transfection assays in several different cell types, including the myeloid lineage. By comparison, this activity is less potent than that displayed by 2 other MLL fusion proteins with similar characteristics, ie, MLL-ENL and MLL-ELL. Interestingly, AF10 contains at least 2 distinct activation domains, only one of which is necessary for myeloid immortalization. This suggests that transcriptional activation per se is not a sufficient contribution, perhaps reflecting promoter-specific or other required effector properties that are not completely recapitulated under the experimental conditions of our transient transcriptional assays. Nevertheless, both of the highly conserved helical domains of AF10 that contribute to the observed modest transactivating function are required for myeloid immortalization. How these domains may interact with the transcriptional machinery remains unclear, although LZ domains mediate homodimerization or heterodimerization in a number of transcriptional activators. One possibility is that the AF10 LZ may facilitate homodimerization or oligomerization of 5′MLL, which results in transcriptional activation.28 However, we have been unable to demonstrate any propensity for the AF10 LZ to homodimerize in vitro (unpublished observations, 2001). Thus, a more likely mechanism would appear to be LZ-mediated interaction with heterologous proteins. Recently, the LZ of AF10 has been reported to interact with GAS41,29 the product of a gene amplified in glioblastomas.30 Although the function of GAS41 is not known, it shares limited similarity with MLL fusion partners ENL31 and AF9 as well as their yeast homolog ANC1, a component of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex.32Interestingly, GAS41 and AF10 interact in vitro with INI1,29 the human homolog of SNF5. Thus, an intriguing possibility is that MLL-AF10 may recruit a chromatin-remodeling complex to MLL target genes, a possibility previously suggested for MLL-ENL as well.13

The LZ of AF10, however, is not sufficient for either immortalization or transactivation. Both the LZ and OM, 2 adjacent α-helical domains, are required. The highly conserved OM domain has not been previously described, but it may affect the selectivity or stability of interactions between the LZ and heterologous proteins. The sequence preservation and relative positioning of both domains in AF10-related proteins in diverse species suggests that they mediate critical functions of the native AF10 protein. A possible role for AF10 family proteins in heterochromatin-mediated transcriptional silencing is suggested by recent observations that the Drosophilahomolog (Alhambra or dAF10) physically and genetically interacts with heterochromatin protein HP1 and suppresses position effect variegation,33 whereas its mutation compromises polycomb-mediated transcriptional repression (L. Perrin and J.-M. Dura, personal communication, 2001). These observations raise the possibility that the oncogenic role of MLL-AF10 may involve perturbed polycomb-mediated repression at MLL target genes through the conserved effector domains of AF10 defined in our studies.

Finally, our studies suggest that there may be structural and functional commonalities among several MLL fusion partners. Despite their lack of primary sequence homology, the minimal transforming domains of AF10, ENL, and ELL all possess predicted α- helical motifs that display transcriptional effector properties that read out in transient transcriptional activation assays. An interesting variation on this paradigm is the forkhead domain fusion partner AFX. A strong transactivation domain in AFX is necessary but not sufficient for transformation,34 which requires a second weaker activation domain. This suggests that there are qualitative differences in the transcriptional effector properties of MLL fusion partners whose contributions to leukemogenesis may not strictly correlate with levels of constitutive transcriptional activation. These effector properties may colocalize in single domains of AF10, ENL, and ELL but appear to be separated in AFX. Identifying these functions and elucidating the pathways that are perturbed by their interaction with MLL will provide a clearer understanding of normal and pathologic myeloid development.

The authors thank Carmencita Nicholas for expert technical assistance and Caroline Tudor for photographic support.

Supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA55029). J.F.D. was supported by Public Health Service grant no. 5T32CA09151 awarded by the National Cancer Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Michael L. Cleary, Dept of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Dr, Stanford, CA 94305; e-mail: mcleary@stanford.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal