Key Points

Mutations in MLL-rearranged AML are associated with MLL fusion partners, and KRAS mutations frequently coexist with high-risk MLL fusions.

KRAS mutations are novel adverse prognostic factors in MLL-rearranged AML, regardless of fusion partner-based risk subgroup.

Abstract

Mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) gene rearrangements are among the most frequent chromosomal abnormalities in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). MLL fusion patterns are associated with the patient’s prognosis; however, their relationship with driver mutations is unclear. We conducted sequence analyses of 338 genes in pediatric patients with MLL-rearranged (MLL-r) AML (n = 56; JPLSG AML-05 study) alongside data from the TARGET study’s pediatric cohorts with MLL-r AML (n = 104), non–MLL-r AML (n = 581), and adult MLL-r AML (n = 81). KRAS mutations were most frequent in pediatric patients with high-risk MLL fusions (MLL-MLLLT10, MLL-MLLT4, and MLL-MLLT1). Pediatric patients with MLL-r AML (n = 160) and a KRAS mutation (KRAS-MT) had a significantly worse prognosis than those without a KRAS mutation (KRAS-WT) (5-year event-free survival [EFS]: 51.8% vs 18.3%, P < .0001; 5-year overall survival [OS]: 67.3% vs 44.3%, P = .003). The adverse prognostic impact of KRAS mutations was confirmed in adult MLL-r AML. KRAS mutations were associated with adverse prognoses in pediatric patients with both high-risk (MLLT10+MLLT4+MLLT1; n = 60) and intermediate-to-low–risk (MLLT3+ELL+others; n = 100) MLL fusions. The prognosis did not differ significantly between patients with non–MLL-r AML with KRAS-WT or KRAS-MT. Multivariate analysis showed the presence of a KRAS mutation to be an independent prognostic factor for EFS (hazard ratio [HR], 2.21; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35-3.59; P = .002) and OS (HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.01-3.31; P = .045) in MLL-r AML. The mutation is a distinct adverse prognostic factor in MLL-r AML, regardless of risk subgroup, and is potentially useful for accurate treatment stratification. This trial was registered at the UMIN (University Hospital Medical Information Network) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR; http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm) as #UMIN000000511.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a genetically and clinically heterogeneous disease.1,2 Mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL; gene symbol, KMT2A) gene rearrangements are among the most common chromosomal abnormalities in AML.3,4 The proportion of MLL-rearrangements in AML is higher in younger patients: ∼40% in infant AML, 20% in pediatric AML, and 5% to 10% in adult AML.5-8 MLL-rearranged (MLL-r) AML is heterogeneous, with more than 60 different fusion partner genes identified.9 Morphologically, most MLL-r AML is classified as the French-American-British (FAB)-M4 or FAB-M5 type.10,11 Although all patients with MLL-r AML had long been thought to have a poor prognosis, a study showed that each patient’s prognosis varies considerably according to the MLL fusion partner.12 For example, t(9;11)(p22;q23)/MLL-MLLT3(AF9), the most common fusion pattern, is associated with intermediate risk, whereas t(1;11)(q21;q23)/MLL-MLLT11 is associated with low risk, and t(10;11)(p12;q23)/MLL-MLLT10(AF10) and t(6;11)(q27;q23)/MLL-MLLT4(AF6) are associated with high risk. Therefore, several fusion genes are currently used for risk stratification of AML treatment.3,4,13

Compared with other AML subtypes, the number of coexisting driver mutations is lower in MLL-r AML.1,8 RAS pathway genes are frequently mutated.14-16 Other pathways associated with epigenetic regulation, transcription factors, the cohesin complex, and the cell cycle have also been identified in MLL-r AML17 ; however, little is known about the distribution and prognostic significance of driver mutations, according to specific MLL fusion partner genes, because the cohorts affected have been too small to allow for detailed analysis. In this study, we examined data from 160 pediatric and 81 adult patients with MLL-r AML, as well as control data from 581 patients with pediatric non–MLL-r AML, and we identified fusion partner–specific mutation patterns and KRAS mutations as distinct adverse prognostic factors in MLL-r AML, regardless of risk subgroup.

Methods

Patients and study protocol

The AML-05 study is a Japanese nationwide multi-institutional study of children (age, <18 years) with de novo AML, conducted by the Japanese Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma Study Group (JPLSG). Patients (n = 485) were enrolled from 1 November 2006 through 31 December 2010. Details of the schedules and treatment regimens in this trial have been described previously.18 Among the 485 enrolled patients, 56 with MLL-r AML were available for this study, all of whom were the same as those analyzed in a previous study.17

In addition, mutation and clinical data were collected from patients with MLL-r AML in the TARGET cohort.8 Of those, 104 and 581 patients with MLL-r AML and non–MLL-r AML, respectively, were identified, and their clinical data were obtained from the TARGET Data Matrix (https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/target/data-matrix). In addition, mutation data and clinical information from adult MLL-r AML patients, collected at the MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory, were analyzed. Among 85 adult patients with de novo MLL-r AML in the previous study,14 4 without survival data were excluded, leaving 81 available for this study. The survival data were updated from the publication date.

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles set down in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committees of all participating institutions. All patients, or their parents or guardians, provided written informed consent.

DNA sequencing and mutation calling

As previously reported,17 338 target genes (supplemental Table 1) in 56 MLL-r AML samples from the AML-05 study were screened for mutations by targeted capture sequencing. Target genes were selected based on the 4 criteria. They must be (1) known driver genes in myeloid malignancies or other neoplasms; (2) associated with myeloid malignancies; (3) mutated, as detected by whole-exome sequencing in the previous study17 ; and (4) therapeutically targetable genes.

Sample preparation, sequencing, and data analyses were performed as previously reported.17 Target enrichment was conducted with a SureSelect custom kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), which was designed to capture all coding exons of the 338 target genes and 1216 single-nucleotide polymorphisms for copy number analysis. Candidate somatic mutations were selected using the following parameters: (1) supported by ≥5 reads in tumor samples; (2) a variant allele frequency in tumor samples >0.02; (3) P < 0.0001 (calculated using EBCall19 ); and (4) found in both positive- and negative-strand reads. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms with minor allele frequencies >0.001, those with synonymous mutations, and those in nontargeted genes were excluded, as were mutations with variant allele frequency 0.4 to 0.6, unless the same mutations were reported in the COSMIC database (Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer; https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk), as identified in hematological malignancies, or were nonsense/frameshift mutations in known tumor-suppressor genes in myeloid malignancies.

Mutation data for samples from 104 and 581 TARGET cohort patients with MLL-r AML and non–MLL-r AML, respectively, were collected as described in a previous publication.8 The methods of sequencing and data analysis of the samples from 85 adult patients with MLL-r AML at the MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory have been reported.14

Lollipop plots were generated using ProteinPaint (https://pecan.stjude.org/proteinpaint/) to visualize the KRAS mutations.20

Statistical analysis

Survival analyses were performed by the Kaplan-Meier method in Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), and groups were compared by using an unstratified log-rank test or the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Categorical variables were compared by using Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate analysis was performed with JMP Pro 14 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of 160 pediatric patients with MLL-r AML (56 and 104 from the AML-05 and TARGET cohorts, respectively) are detailed in Table 1. Sex, age, and white blood cell count (WBC) were similar between the AML-05 and TARGET cohorts. Median age at diagnosis for the entire cohort was 3.9 years (range, 0.0-18.2). In both cohorts, most cases were classified as FAB-M5 (AML-05, 58.9%; TARGET, 63.5%) or FAB-M4 (AML-05, 25.0%; TARGET, 15.4%). The frequency of fusion partners was also similar; in both cohorts, the most frequent partner was MLLT3 (AML-05, 44.6%; TARGET, 36.5%), followed by MLLT10 (AML-05, 19.6%; TARGET, 25.0%) and ELL (AML-05, 17.9%; TARGET, 12.5%).

Distribution of driver mutations in MLL-r AML

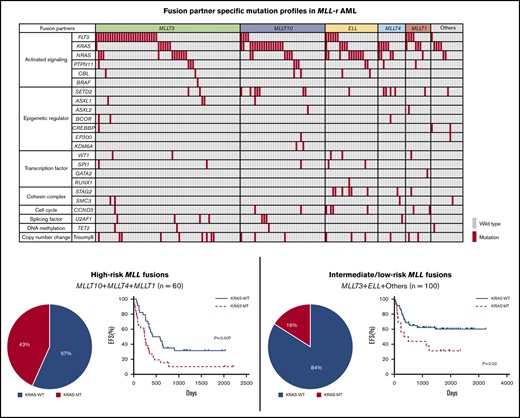

The landscape of driver mutations in 160 pediatric patients with MLL-r AML is shown in Figure 1. The most frequent mutations were identified in activated signaling pathway genes (FLT3, KRAS, NRAS, PTPN11, CBL, and BRAF; 114 of 160 patients; 71.3%). Mutations in genes associated with epigenetic regulation (SETD2, ASXL1, ASXL2, BCOR, CREBBP, EP300, and KDM6A; 27 of 160 patients; 16.9%), transcription factors (WT1, SPI1, GATA2, and RUNX1; 12 of 160 patients; 7.5%), and the cohesin complex (STAG2 and SMC3; 12 of 160 patients; 7.5%) were also recurrently detected.

Mutational landscape of MLL-r AML. Distribution of driver mutations in patients with MLL-r AML (n = 160), according to MLL fusion partner.

Mutational landscape of MLL-r AML. Distribution of driver mutations in patients with MLL-r AML (n = 160), according to MLL fusion partner.

The frequencies of the driver mutations differed according to MLL fusion partner genes. FLT3 mutations (n = 42), including FLT3 internal tandem duplications (FLT3-ITD; n = 7) and FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain mutations affecting codons 835 and 836 (n = 16), were more frequent in patients with MLL-MLLT3 (27 of 63; 42.9%) and MLL-MLLT1 (4 of 11; 36.4%). RAS pathway genes were more frequently mutated in specific groups, such as KRAS in those with MLL-MLLT10 (17 of 37; 45.9%), MLL-MLLT4 (5 of 12; 41.7%), MLL-MLLT1 (3 of 11; 27.3%), and other (4 of 14; 28.6%) fusions, and NRAS in those with MLL-ELL (10 of 23; 43.5%) and MLL-MLLT4 (4 of 12; 33.3%) fusions. Other pathway mutations also coexisted with specific partner genes; SETD2 mutations were frequent in patients with MLL-MLLT4 fusions (4 of 12; 33.3%), and STAG2 mutations were frequent in those with MLL-ELL (6 of 23; 26.1%). These data suggest that each MLL fusion group has a unique pattern of driver mutations and, interestingly, that KRAS mutations are more frequent in patients with high-risk translocations (MLL-MLLT10 and MLL-MLLT4).

Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in MLL-r AML

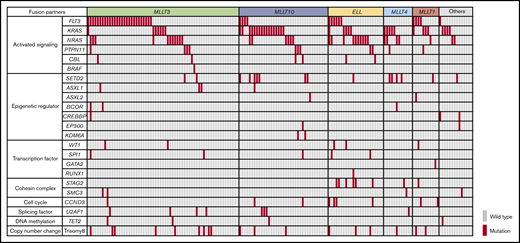

Next, we examined the prognostic significance of each driver mutation in patients with MLL-r AML. Among 8 frequently mutated genes (≥5%: ≥8 patients with mutations among the 160 patients) and 1 copy number change (trisomy 8), only KRAS mutations were associated with an adverse prognosis for event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS; Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 1). Compared with patients without KRAS mutations (KRAS-WT; n = 118), those with KRAS mutations (KRAS-MT; n = 42) had significantly inferior prognoses (5-year EFS: 51.8% vs 18.3%, P < .0001; 5-year OS: 67.3% vs 44.3%, P = .003). Type and distribution of KRAS mutations were similar in the TARGET and AML-05 cohorts; most mutations were missense and located in the G12/G13 hotspots (supplemental Figure 2). Detailed information on KRAS mutations according to MLL fusion type is provided in supplemental Table 2. Double KRAS mutations were identified in 3 patients (2 with MLL-MLLT10 fusions and 1 with an MLL-MLLT3 fusion). There were no obvious correlations between the location of KRAS mutations and MLL fusions, except that the KRAS G13 mutation was not detected in MLL-ELL leukemias.

Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations. (A) Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in pediatric patients with MLL-r AML who were in the TARGET and AML-05 cohorts (n = 160). (B) Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in pediatric patients with non–MLL-r AML enrolled in the TARGET cohort (n = 581). (C) Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in adult patients with MLL-r AML in the MLL laboratory (n = 81). The log-rank test was used for survival estimates.

Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations. (A) Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in pediatric patients with MLL-r AML who were in the TARGET and AML-05 cohorts (n = 160). (B) Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in pediatric patients with non–MLL-r AML enrolled in the TARGET cohort (n = 581). (C) Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in adult patients with MLL-r AML in the MLL laboratory (n = 81). The log-rank test was used for survival estimates.

We also examined whether the adverse prognostic significance of KRAS mutations is abrogated by allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) in first complete remission (CR1). Among the 42 pediatric patients with MLL-r AML and KRAS mutations, SCT data were available for 39. Compared with patients who did not undergo allo-SCT in CR1 (n = 35), those who did (n = 4) had a favorable prognosis; however, the difference was not statistically significant (non-SCT vs SCT: 5-year EFS: 16.1% vs 50.0%, P = .24; 5-year OS: 38.9% vs 50.0%, P = .49; supplemental Figure 3).

In AML, FLT3 mutations (especially FLT3-ITD) are important adverse prognostic indicators21 ; therefore, we analyzed their prognostic significance relative to KRAS mutations. Survival was compared in patients with FLT3-ITD (n = 4); other FLT3 mutations, including those in the tyrosine kinase domain (indicated as FLT3-MT, n = 31); KRAS mutations (KRAS-MT, n = 37); both FLT3 and KRAS mutations (FLT3&KRAS-MT, n = 4); and neither FLT3 nor KRAS mutations (others; n = 81) (supplemental Figure 4). Two patients with FLT3-ITD and other FLT3 mutations and 1 patient with FLT3-ITD and KRAS mutations were excluded because of the small samples. The results showed that the 2 groups with KRAS mutations (KRAS-MT and FLT3&KRAS-MT) had a poorer prognosis than the other 3 groups without KRAS mutations (FLT3-ITD, FLT3-MT, and others).

KRAS mutations have not been reported as a prognostic factor in pediatric AML; therefore, we examined their prognostic significance in patients with non–MLL-r AML (n = 581; Figure 2B). There were no significant differences in 5-year EFS (50.6% vs 54.5%; P = .55) or 5-year OS (67.1% vs 64.9%; P = .84) between patients with KRAS-WT (n = 533) or KRAS-MT (n = 48) non–MLL-r AML.

In addition, to confirm the adverse prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in MLL-r AML, we analyzed adult patients with MLL-r AML (n = 81; Figure 2C). The locations and types of KRAS mutations in adult patients with MLL-r AML were similar to those in pediatric patients with MLL-r AML (supplemental Figure 2). Compared with adult patients with KRAS-WT (n = 61), patients with KRAS-MT (n = 20) had a significantly adverse 5-year OS (33.4% vs 27.3%; P = .02), but not 5-year EFS (17.3% vs 20.5%; P = .10); however, patents carrying KRAS-MT had shorter median survival times for both EFS and OS (KRAS-WT vs KRAS-MT; EFS: 308 days vs 89 days; OS: 528 days vs 89 days). Therefore, rather than use the log-rank test, we analyzed the data by using the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test, which gives more weight to deaths at early time points and found significant differences in both EFS (P = .009) and OS (P = .007). Overall, these results suggest that KRAS mutations can be an adverse prognostic factor in MLL-r AML and that the prognostic significance may be limited to this disease subgroup.

Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations according to MLL fusion partner

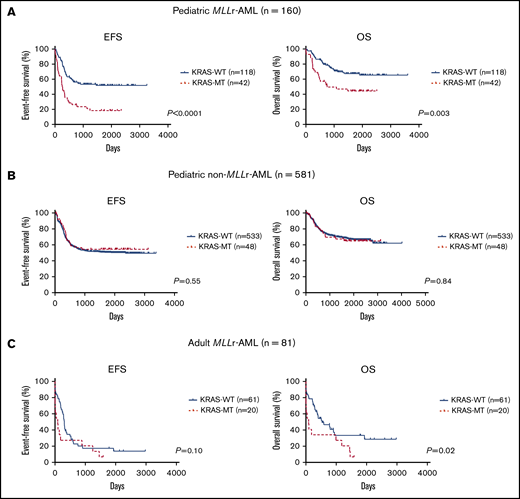

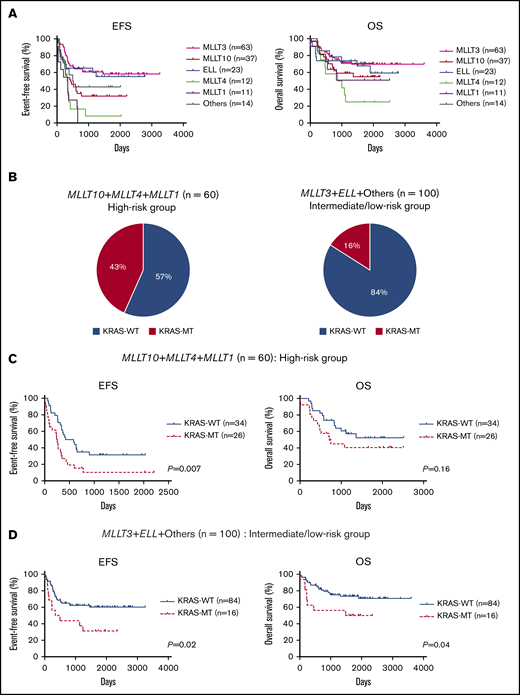

We also analyzed the prognostic significance of KRAS mutations according to MLL fusion partner. First, the prognosis of patients was compared for each fusion partner gene (Figure 3A). Consistent with a previous report,12 patients with MLL-MLLT10 (n = 37), MLL-MLLT4 (n = 12), or MLL-MLLT1 (n = 11) had poor prognoses compared with those with other fusion types. Therefore, we dichotomized patients into high-risk (MLLT10+MLLT4+MLLT1; n = 60) and intermediate-to-low-risk (MLLT3+ELL+others; n = 100) groups. The frequency of KRAS mutation was significantly elevated in the high-risk group (26 of 60; 43.3%) relative to the intermediate-to-low–risk group (16 of 100; 16.0%; P = .0002; Figure 3B). Further, in the high-risk group, patients with KRAS-MT (n = 26) had significantly more adverse prognoses than did patients with KRAS-WT (n = 34; 5-year EFS: 31.5% vs 10.3%, P = .007; 5-year OS: 52.4% vs 40.5%, P = .16; Figure 3C). Moreover, patients with KRAS-MT in the intermediate-to-low-risk group (n = 16) had significantly more adverse prognoses than did patients with KRAS-WT (n = 84; 5-year EFS: 60.3% vs 31.3%, P = .02; 5-year OS: 73.4% vs 50.0%, P = .04; Figure 3D). When we analyzed the prognosis of patients for each MLL fusion group, patients with KRAS-MT generally had inferior prognoses vs those with KRAS-WT; however, the difference was significant for only a few MLL fusion groups because of the small subgroup sample sizes (supplemental Figure 5). These results suggest that KRAS mutations can be adverse prognostic factors in patients with MLL-r AML, regardless of the risk of MLL fusion types.

Prognostic significance of fusion partners and KRAS mutations according to risk subgroup based on fusion patterns in MLL-r AML. (A) Comparison of EFS and OS in patients, according to MLL fusion partners. (B) Frequency of KRAS mutations in the high-risk group (MLLT10+MLLT4+MLLT1; n = 60) and intermediate-to-low–risk group (MLLT3+ELL+others; n = 100). (C-D) Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in pediatric patients with MLL-r AML with high-risk fusion partners (MLLT10+MLLT4+MLLT1; n = 60) (C) and with intermediate-to-low–risk fusion partners (MLLT3+ELL+others; n = 100) (D).

Prognostic significance of fusion partners and KRAS mutations according to risk subgroup based on fusion patterns in MLL-r AML. (A) Comparison of EFS and OS in patients, according to MLL fusion partners. (B) Frequency of KRAS mutations in the high-risk group (MLLT10+MLLT4+MLLT1; n = 60) and intermediate-to-low–risk group (MLLT3+ELL+others; n = 100). (C-D) Prognostic significance of KRAS mutations in pediatric patients with MLL-r AML with high-risk fusion partners (MLLT10+MLLT4+MLLT1; n = 60) (C) and with intermediate-to-low–risk fusion partners (MLLT3+ELL+others; n = 100) (D).

Multivariate analysis

Finally, we investigated whether KRAS mutation is an independent prognostic factor in patients with MLL-r AML. We performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis that included the following variables: age, WBC, MLL fusion gene, driver mutations, and trisomy 8 (Table 2). Mutations with lower frequencies (<5%, <8 mutations among 160 cases), which made the Cox regression model unstable, were excluded from this analysis. The results indicated that KRAS mutation was the only prognostic factor predicting both poor EFS (hazard ratio [HR], 2.21; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35-3.59; P = .002) and poor OS (HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.01-3.31; P = .045). These results suggest that KRAS mutation is a prognostic factor in patients with MLL-r AML, independent of age, WBC, MLL fusion partner, and other driver mutations.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the distribution of driver mutations in MLL-r AML carrying each MLL fusion by mutation profiling, revealing several associations between MLL fusions and driver mutations, as follows: FLT3 mutations were frequent in MLL-MLLT3 and MLL-MLLT1 AML; KRAS mutations were frequent in MLL-MLLT10, MLL-MLLT4, and MLL-MLLT1; NRAS mutations were frequent in MLL-ELL and MLL-MLLT4; SETD2 mutations were frequent in MLL-MLLT4; and STAG2 mutations were frequent in MLL-ELL leukemia. These patterns may reflect the cooperative mechanisms involved in MLL fusion and driver mutation–induced leukemogenesis.

In MLL-r AML, the number of cooperating driver mutations has been reported to be fewer than in other disease subtypes,1,8 and the prognostic significance of driver mutations has not been fully elucidated. Our previous study revealed that patients with MLL-r AML with driver mutations may have an adverse prognosis,17 although the impact of each driver mutation was unclear because of the small samples. In this study, by analyzing data from 160 pediatric and 81 adult patients with MLL-r AML, we found that KRAS mutations were associated with adverse prognoses in pediatric and adult patients. Interestingly, KRAS mutations significantly coexisted with high-risk MLL fusions, such as MLL-MLLT10, MLL-MLLT4, and MLL-MLLT1. In a multivariate analysis, KRAS mutation was an independent adverse prognostic factor, whereas there were no statistically significant findings for MLL fusions. Therefore, the adverse prognoses of patients with high-risk MLL fusions may be explained by the frequency of KRAS mutations. According to the recommendations from an international expert pediatric AML panel, patients with several MLL fusions, including MLL-MLLT4 and MLL-MLLT10, are categorized as an adverse prognostic group, whereas those with other MLL fusions are categorized as an intermediate prognostic group; no driver mutations were used for risk stratification.3 In our data, patients with KRAS-MT and intermediate-to-low-risk MLL fusions had worse prognoses, comparable with those of patients with high-risk MLL fusions without KRAS mutations. Moreover, among patients with high-risk MLL fusions, those with KRAS-MT had extremely poor prognoses. These data suggest that KRAS mutations are useful for accurate risk stratification and should be considered for use as a screening test, in addition to identification of the MLL fusion type. We also found that the adverse prognostic significance of KRAS mutations may be abrogated by allo-SCT in CR1. Analysis of a larger cohort is needed to validate our findings in a future study.

KRAS mutations were not associated with adverse prognosis in non–MLL-r AML, and the importance of KRAS examination for risk stratification may be higher in patients with MLL-r AML than in those with non–MLL-r AML. AML is a heterogeneous disease and RAS pathway mutations are frequent events in several disease subtypes, including core binding factor AML.1,2,22 Therefore, there may be some disease subtypes that can be risk stratified by KRAS mutations. A detailed analysis of a large number of patients with non–MLL-r AML should also be included in future studies.

Our findings may be applicable not only for risk stratification but could also suggest novel treatments. Although KRAS mutations are among the most frequent genetic aberrations in cancer, effective treatments targeting KRAS have yet to be developed23,24 ; however, several KRAS inhibitors specific for the G12C mutant have been developed recently and show remarkable results for treatment of solid tumors with KRAS mutations.25-28 A pan-KRAS inhibitor, targeting both G12 and G13 mutations, has also entered clinical study.29 In our study, KRAS mutations were frequent (>40%) in patients with AML with high-risk MLL fusions, and most of the mutations detected were in G12 and G13, suggesting that inhibitors targeting these mutations may be promising treatments for these patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Human Genome Center, Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, for providing Supercomputing resources.

This work was supported by a Grant in-Aid from the Agency for Medical Research and Development (Project for Development of Innovative Research on Cancer Therapeutics [P-DIRECT]), the Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution [P-CREATE], and Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control) and JSPS KAKENHI (JP19K16832).

Authorship

Contribution: H.M. and K.Y. analyzed the clinical and sequencing data; K.N., Y.H., M.H., and Y.I. helped with the analysis; Y. Shiozawa, Y. Shiraishi, K.C., H.T., A.O., and S.M. developed the sequence data processing pipelines; H.M., K.Y., Y.N., J.T., and H.U. performed the sequencing; N.K., D.T., T.T., A.T., and S.A. collected clinical samples; M.M., and C.H. provided the adult patient sequencing data and clinical information; Y.K., S.O., and S.A. supervised the project; and H.M. and K.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Souichi Adachi, Department of Human Health Sciences, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, 53 Kawahara-cho, Shogoin, Sakyoku, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan; e-mail: adachiso@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

Original data may be obtained by e-mail request to the corresponding author Souichi Adachi (e-mail: adachiso@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp).

H.M. and K.Y. contributed equally to this study.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.