Key Points

ADAMTS13 sSNVs affect mRNA thermodynamic stability and may disturb mRNA-splicing sites.

Synonymous variations may affect ADAMTS13 function and contribute to large variability in protein expression levels in healthy individuals.

Abstract

The effects of synonymous single nucleotide variants (sSNVs) are often neglected because they do not alter protein primary structure. Nevertheless, there is growing evidence that synonymous variations may affect messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and protein conformation and activity, which may lead to protein deficiency and disease manifestations. Because there are >21 million possible sSNVs affecting the human genome, it is not feasible to experimentally validate the effect of each sSNV. Here, we report a comprehensive series of in silico analyses assessing sSNV impact on a specific gene. ADAMTS13 was chosen as a model for its large size, many previously reported sSNVs, and associated coagulopathy thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Using various prediction tools of biomolecular characteristics, we evaluated all ADAMTS13 sSNVs registered in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database of single nucleotide polymorphisms, including 357 neutral sSNVs and 19 sSNVs identified in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. We showed that some sSNVs change mRNA-folding energy/stability, disrupt mRNA splicing, disturb microRNA-binding sites, and alter synonymous codon or codon pair usage. Our findings highlight the importance of considering sSNVs when assessing the complex effects of ADAMTS13 alleles, and our approach provides a generalizable framework to characterize sSNV impact in other genes and diseases.

Introduction

Although commonly assumed to be silent, synonymous single nucleotide variants (sSNVs) can cause protein deficiency or dysfunction severe enough to lead to disease1-3 through various mechanisms. Synonymous variants may alter constitutive splice sites or activate cryptic splice sites, which can result in unstable messenger RNA (mRNA) or defective protein.2 Synonymous changes may affect thermodynamic stability and secondary structure of mRNA or codon usage frequency, resulting in altered translational kinetics and cotranslational folding of a protein.2,4 Recent studies suggest that intermittent ribosome stalling at key mRNA regulatory sites can affect protein abundance, folding, and even posttranslational modifications, and the placement of certain stable structural elements within the mRNA sequence is not random.2,5-7 Moreover, synonymous variants can disturb microRNA (miRNA)-binding sites in the coding sequence, which can lead to developmental defects and disease.8

Synonymous variants can affect cytosine-guanine dinucleotide (CpG) sites, guanine-cytosine (GC) content, and codon usage biases, which may change the rate of translation due to ribosomal pausing.9 Several studies found that ribosomal pauses relate to cotranslational folding of protein domains, which in turn determines the final protein conformation. Ultimately, by affecting gene regulatory signature, mRNA structure, and pre-mRNA processing, sSNVs can influence protein characteristics, including expression, function, and immunogenicity.10-12

ADAMTS13 (MIM:604134) controls the hemostatic function of von Willebrand factor (VWF; MIM: 613160) by splitting highly adhesive, ultra-large VWF multimers into smaller forms.13 VWF is critical to the initial stage of thrombosis by tethering platelets to the endothelium at sites of vascular injury.14 Regulation of VWF by ADAMTS13 prevents the spontaneous formation of platelet thrombi. Deficiency of ADAMTS13 increases VWF thrombogenic potential and may lead to microvascular thrombosis such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)15,16 or congenital TTP, also known as Upshaw-Schulman syndrome (USS).17 ADAMTS13 plays a crucial role in pediatric stroke pathogenesis,18 and lower levels of ADAMTS13 have been associated with increased risks of coronary heart diseases and myocardial infarction.19 Recently, clinical studies have shown the development of acquired TTP followed by COVID-19 infection and a strong association between low ADAMTS13 plasma levels and increased mortality in patients with COVID-19.20

The ADAMTS13 gene is located on chromosome 9 and is ∼37 kb long containing 29 exons. ADAMTS13 mRNA is ∼4 kb long and encodes 1427 amino acids.21,22 This multidomain protein comprises a signal peptide, propeptide, metalloprotease, disintegrin-like domain, first thrombospondin type 1 repeat (TSP1), Cysteine-rich, and spacer domains. The distal C-terminus includes 7 additional TSP repeats and two CUB (C1r/C1s, urinary epidermal growth factor, bone morphogenetic protein) domains, that are unique for ADAMTS13.23 The metalloprotease domain of ADAMTS13 modulates ADAMTS13 protein activity via cooperative binding to one Zn2+ ion and three Ca2+ ions.24,25

Among human ADAMTS13 variants listed in a database of single nucleotide polymorphisms (dbSNP), ∼200 disease-causative SNVs have been identified in patients with TTP,26-28 all of which were non-synonymous and detected as haplotypes. Other SNVs may result in reduced plasma ADAMTS13 activity29,30 and disrupted ADAMTS13–VWF interactions by changing untranslated regions (UTRs), splice regulatory regions, or the coding sequence. In addition, various truncated forms of ADAMTS13 are detectable in plasma, and several alternatively spliced mRNA variants have been characterized.31-37

Three genome-wide association studies (GWAS) revealed high heritability of ADAMTS13 levels (59.1%) and identified hundreds of non-synonymous and synonymous SNVs at the ADAMTS13 locus that collectively explained ∼20.0% of large ADAMTS13-level variation in healthy individuals.30,38,39 Of 376 sSNVs registered in the National Center for Biotechnology Information dbSNP database, 357 sSNVs have been identified in healthy individuals, and 19 sSNVs have been identified in patients with USS40 (supplemental Table 1). The impact of USS-associated sSNVs in the context of deleterious co-occurring mutations is currently unknown. Such sSNVs may have an additive negative impact, or they may help to enhance ADAMTS13 expression. For instance, the USS synonymous variant c.354G>A (rs28571612) yielded higher extracellular and intracellular ADAMTS13 expression levels and higher specific activity according to in vitro measurements.10,41

Due to limited data from GWAS and few experimental validations, the impact of specific sSNVs on ADAMTS13 function remains difficult to interpret. Nevertheless, prior studies show that variants in the ADAMTS13 gene resulting in deficient ADAMTS13 activity may disturb VWF activity and lead to coagulopathies such as USS.15 Understanding the factors that contribute to ADAMTS13 expression and disturb normal protein activity could help reduce diagnostic errors, prevent TTP development, and improve treatment.

Considering the substantial number of observed synonymous variants, comprehensive experimental verification is difficult to perform. Use of computational predictors and modeling can reveal sSNVs that are most likely to affect protein function and disease.3 This approach can help focus experimental studies on a smaller subset of synonymous variants most likely to have a detectable impact on protein characteristics.

To better understand the contributions sSNVs may make to protein biogenesis using ADAMTS13 as a model, we performed comprehensive in silico analysis of all known ADAMT13 sSNVs. Our results highlight sSNVs that may alter mRNA splicing, change mRNA-folding energy, disturb miRNA-binding sites, and affect synonymous codon usage. This in silico analysis provides a generalizable approach to characterize the effects of sSNVs influencing other genes and diseases.

Methods

ADAMTS13 sSNV selection

The ADAMT13 variants were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information dbSNP database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?locusId=11093; GRCh38.p7). All SNVs from ADAMTS13 were filtered to include only synonymous variants in the open reading frame. Of >1000 SNVs, all 376 sSNVs were selected for further evaluation and compared with the wild-type (WT) ADAMTS13 (NM_139025). All sSNVs obtained from the dbSNP (supplemental Excel Worksheet 1) include 357 neutral variants and 19 sSNVs that were identified in patients with USS (USS variants). Although the USS variants are labeled as “being-likely” to cause the disease, this has not yet been confirmed. To our knowledge, there are no confirmed disease-associated ADAMTS13 sSNVs.

In silico studies of ADAMTS13 sSNVs

Determination of mRNA-folding energy, stability, and structure were performed by using mFold,42 NUPACK,43 kineFold,44 remuRNA,45 and RNAFold.46 Splicing impact of ADAMTS13 sSNVs was evaluated by using MaxEntScan (MES),47 NNsplice,48 SpliceSiteFinder-like,49 and GeneSplicer.50

Evaluation of miRNA-binding sites within the coding region of ADAMTS13 sSNVs was performed by using miRDB,51,52 Paccmit-CDS,53,54 and TargetScan.55 Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) and relative synonyms bicodon usage (RSBCU) were calculated as previously described.43,56 Codon pair score without natural log (CPS),57 rare codon (RC) enrichment,58 and codon adaptation index (W)56 were computed as previously described. RC clustering for ADAMTS13 sSNVs was computed by using %MinMax.59 Protein folding energy was estimated by using a coarse-grained cotranslational folding energy model.58

Complete descriptions of the in silico methods are given in the supplemental Methods, and data produced are provided in Excel Worksheets 1 to 3.

Results

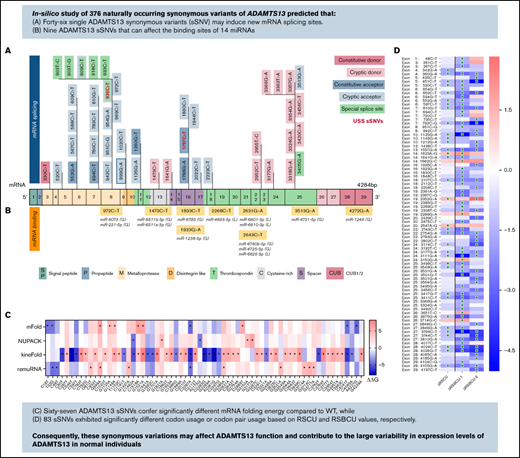

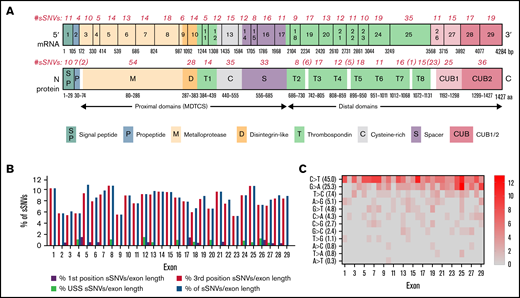

Synonymous mutation patterns in ADAMTS13

A total of 376 naturally occurring sSNVs of ADAMTS13, including 357 from a healthy population and 19 from patients with USS, were identified in the dbSNP; they affect almost 9% of nucleotides in the mRNA of ADAMTS13 and >26% of codons. Most sSNVs have been identified in exon 25. Many sSNVs have been found within the metalloprotease domain and C-terminal region of ADAMTS13, in exons 24 to 29, which encode the TSP7-8 and CUB1-2 domains (Figure 2A).

ADAMTS13 synonymous variant characteristics. (A) Schematic diagram of ADAMTS13 exons and encoded protein domains with the number of sSNVs in each exon and domain (in italic red). (B) Proportion of 376 variants present in first codon position (solid red) or in third codon position (red outline). Proportion of sSNVs found in patients with USS (yellow). Proportion of variants present in each exon, normalized by exon length (gray). (C) Distribution of 12 possible nucleotide substitutions of synonymous mutations across ADAMTS13 exons and the percentage of variants with given nucleotide substitution provided in parentheses.

ADAMTS13 synonymous variant characteristics. (A) Schematic diagram of ADAMTS13 exons and encoded protein domains with the number of sSNVs in each exon and domain (in italic red). (B) Proportion of 376 variants present in first codon position (solid red) or in third codon position (red outline). Proportion of sSNVs found in patients with USS (yellow). Proportion of variants present in each exon, normalized by exon length (gray). (C) Distribution of 12 possible nucleotide substitutions of synonymous mutations across ADAMTS13 exons and the percentage of variants with given nucleotide substitution provided in parentheses.

The distribution of base changes across the sSNVs of ADAMTS13 shows that the most frequently occurring base changes were C>T and G>A, agreeing with prior studies reporting synonymous base pair change frequencies.60,61 Of 19 USS variants, 11 were identified within the TSP2-8 and CUB1 domains. Accounting for exon length, sSNVs most frequently affected exons 1, 5, 8, and 25 (∼11% sSNV per exon length) that encoded signal peptide, metalloprotease, and T8 domains, respectively (Figure 2B). In contrast, sSNVs were rarely found in exons 2 to 4, 9, and 23 encoding the propeptide, metalloprotease, disintegrin-like, and T6 domains, respectively (∼6% sSNV per exon length). The most frequent types of ADAMTS13 sSNVs, C>T and G>A (Figure 2C), lower GC content.

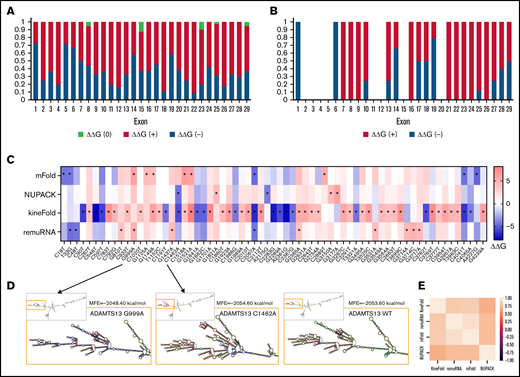

sSNVs may affect RNA-folding energy and secondary structure

We next evaluated RNA-folding energy of ADAMTS13 sSNVs. Such changes may affect antigen and activity levels of the protein. Experimental measurement of mRNA structure remains a challenge, especially to a degree of sensitivity that could detect structural differences resulting from single nucleotide changes.64 However, algorithms such as mFold,42 kineFold,44 remuRNA,45 or NUPAC43 can evaluate the stability of mRNA fragments by calculating Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of possible secondary structures.1

Using these 4 algorithms, we calculated ΔΔG () for all ADAMTS13 sSNVs (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 1A). According to at least one algorithm, 67 sSNVs caused significantly altered folding energy compared with WT (P < .05) (Figure 3B-C). (The supplemental Methods provides a description of P value computation, and supplemental Excel Worksheet 1 provides the P values). Although the sSNVs generally resulted in increased ΔG and were predicted to cause structural instability, we found some sSNVs, particularly in exons 1, 6, 14, and 19, which caused significant decreases in ΔG and thus more stable mRNA structures (Figure 3B). Others have proposed that thermodynamically stable mRNA secondary structures should have a selective advantage.65

ADAMTS13 sSNVs affect the folding energy and mRNA secondary structure. (A) Stacked column plot that displays the proportions of all sSNVs in each exon that decrease ΔΔG (–, blue), increase ΔΔG (+, red), or do not change ΔΔG (0, white) based on average value obtained from all 4 algorithms (see Methods). (B) Stacked column plot that displays the ratio of significantly different sSNVs (P values < .05) in each exon. (C) Synonymous ADAMTS13 variants with significantly (*) different ΔΔG compared with WT as predicted by at least one algorithm (P < .05). (D) Optimal full-length mRNA secondary structure of ADAMTS13 predicted by RNAFold for variants 999G>A and 1462C>A compared with WT ADAMTS13. (E) Correlation between the ΔΔG values obtained by mFold, remuRNA, KineFold, and NUPAC for all 376 ADAMTS13 sSNVs. Differences considered significant in which P < .05 (see supplemental Methods for description of P value computation and supplemental Excel File 1 for P values).

ADAMTS13 sSNVs affect the folding energy and mRNA secondary structure. (A) Stacked column plot that displays the proportions of all sSNVs in each exon that decrease ΔΔG (–, blue), increase ΔΔG (+, red), or do not change ΔΔG (0, white) based on average value obtained from all 4 algorithms (see Methods). (B) Stacked column plot that displays the ratio of significantly different sSNVs (P values < .05) in each exon. (C) Synonymous ADAMTS13 variants with significantly (*) different ΔΔG compared with WT as predicted by at least one algorithm (P < .05). (D) Optimal full-length mRNA secondary structure of ADAMTS13 predicted by RNAFold for variants 999G>A and 1462C>A compared with WT ADAMTS13. (E) Correlation between the ΔΔG values obtained by mFold, remuRNA, KineFold, and NUPAC for all 376 ADAMTS13 sSNVs. Differences considered significant in which P < .05 (see supplemental Methods for description of P value computation and supplemental Excel File 1 for P values).

The synonymous variant c.999G>A results in the highest positive ΔΔG by mFold and remuRNA and consistently positive ΔΔG by the other 2 tools. Variants c.1521G>A and c.2385G>A displayed significantly positive ΔΔG by mFold and kineFold. The lowest negative ΔΔG predicted by mFold was found in variant c.2067C>A. This variant had significantly negative ΔΔG predicted by kineFold and remuRNA and was the only sSNV with significantly negative ΔG calculated by 3 tools. Variant c.1462C>A displayed the lowest negative ΔΔG calculated by NUPAC and significantly negative ΔΔG calculated by kineFold. Finally, the variant c.4041C>T within exon 28 was predicted to significantly decrease stability according to mFold and kineFold (Figure 3C). None of the 19 USS variants (supplemental Figure 1B) and 2 of the 12 high-frequency variants (supplemental Figure 1C) yielded significant ΔΔG.

We next predicted full-length mRNA secondary structure of highly frequent variants (Table 1) and from variants resulting in most positive (c.999G>A) and most negative (c.1462C>A) ΔΔG by RNAfold. ΔG and the optimal mRNA secondary structure of either sSNV differ from those of WT ADAMTS13 mRNA (Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 2; supplemental Table 2).

We observed moderate correlations between ΔΔG for the 4 algorithms used, with the strongest correlation between mFold and remuRNA, whereas kineFold exhibited the weakest correlations among all 4 (Figure 3E). Although few variants were predicted to significantly affect ΔΔG by multiple algorithms, the direction of the impact (increase or decrease) was generally consistent across the different algorithms (Figure 3C).

In summary, numerous sSNVs may affect ADAMTS13 mRNA thermodynamic stability, and these alterations in mRNA secondary structure may have strong effects on gene function and play an important role in disease onset and progression.7,66

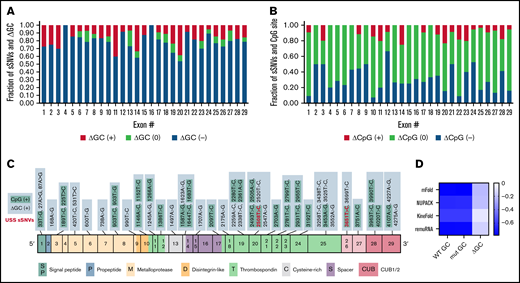

Most ADAMTS13 sSNVs negatively affect CpG sites and decrease GC content

We next examined ADAMTS13 sSNVs for their impact on GC content and CpG sites.

The majority of ADAMTS13 sSNVs reduce GC content (Figure 4A), especially in exons 4, 12, 16, 21, and 24. Of the 376 ADAMTS13 sSNVs, 144 affected CpG sites (Figure 4B). Only 55 sSNVs increased GC content, and 31 sSNVs resulted in a creation of new CpG sites (Figure 4C). The sSNV 33T>G may create a new CpG site in exon 1, potentially affecting the DNA methylation state. Previous studies have shown that CpG sites are frequently methylated9,67 and that methylation in the first exon suppresses gene expression,68 suggesting that this variant may influence ADAMTS13 expression.

Synonymous ADAMTS13 variants affect GC content and CpG sites. (A) Proportion of sSNVs in each exon that increase GC content (red), decrease GC content (blue), or do not affect GC content (green). (B) Proportion of sSNVs in each exon that increase CpG (red), decrease CpG (blue), or do not affect CpG (green). (C) Fifty-five synonymous variants that exhibit ΔGC >0 and 31 sSNVs that created new CpG site (positive CpG) across ADAMTS13 exons. (D) Correlation between folding energy and GC content in variant and WT ADAMTS13. USS variants are shown in red.

Synonymous ADAMTS13 variants affect GC content and CpG sites. (A) Proportion of sSNVs in each exon that increase GC content (red), decrease GC content (blue), or do not affect GC content (green). (B) Proportion of sSNVs in each exon that increase CpG (red), decrease CpG (blue), or do not affect CpG (green). (C) Fifty-five synonymous variants that exhibit ΔGC >0 and 31 sSNVs that created new CpG site (positive CpG) across ADAMTS13 exons. (D) Correlation between folding energy and GC content in variant and WT ADAMTS13. USS variants are shown in red.

As indicators of structural stability, observations of moderate correlations between ΔG and GC content of both WT and variant sequences were not surprising. However, weak correlations were observed between ΔΔG and ΔGC content (Figure 4D).

sSNVs may affect pre-mRNA splicing and miRNA-binding sites

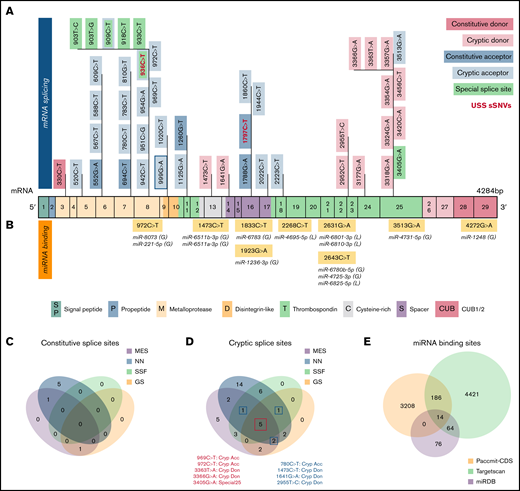

We next examined the possible impact of sSNVs on splicing and miRNA regulation of ADAMTS13 (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Excel Worksheets 2-3), which are 2 common mechanisms by which sSNVs can affect protein structure.2,6 We identified 7 variants predicted to affect constitutive splice donor or acceptor sites (Figure 5A), which might result in exon skipping or intron retention. In addition, 36 variants were identified that may activate cryptic splice sites, and although these cryptic sites are not associated with previously characterized ADAMTS13 splice isoforms, they may still limit expression of constitutive ADAMTS13 transcript. Seven variants were predicted to affect special cryptic sites, which are associated with alternative splice products of ADAMTS13 (NM_139026 and NM_139027). Five of these variants weakened special cryptic sites, potentially resulting in decreased production of alternative transcripts. The c.909C>T variant was predicted to strengthen the special exon 8 acceptor site, potentially decreasing primary transcript expression in favor of the NM_139026 transcript. The c.918C>T variant was predicted to strengthen (NNsplice) and weaken (MES) the special exon 8 acceptor site, making it difficult to predict this variant’s impact. Variants predicted to affect splicing were found in 15 different exons and influence positions that encode several protein domains, including metalloprotease domain (10 sSNVs), disintegrin-like domain (15 sSNVs), Cysteine-rich domain (2 sSNVs), spacer domain (5 sSNVs), and TSP repeats (10 sSNVs) (Figure 5A; supplemental Table 3).

Synonymous variants may affect splicing and miRNA-binding sites within ADAMTS13. (A) ADAMTS13 sSNVs that were predicted to affect splice sites across ADAMTS13 exons and encoded protein domains. Exons are colored consistent with the protein domain(s) they encode. sSNVs that were predicted to affect constitutive donors are highlighted in dark pink, and those predicted to affect constitutive acceptors are highlighted in dark blue. Variants predicted to affect cryptic donors are highlighted in light pink, and those predicted to affect cryptic acceptors are highlighted in light blue. Variants predicted to affect special case exon 8 acceptor or exon 25 donor are colored green. USS variants are shown in red. (B) Variants predicted to affect miRNA-binding sites according to Paccmit-CDS, TargetScan, and miRDB. Consistency of splice affects predictions between MES, NNsplice (NN), SpliceSiteFinder-like (SSF), and GeneSplicer (GS) splice prediction tools for constitutive splice sites (C) and for cryptic and special case cryptic splice sites (D). (E) Venn diagram displays numbers of ADAMTS13 sSNVs that affect miRNA-binding sites as predicted by Paccmit-CDS, TargetScan, and miRDB. Acc, acceptor; C, cysteine-rich; Cryp, cryptic; D, disintegrin-like; Don, donor; M, metalloproteinase; P, propeptide; T1-T8, thrombospondin repeats 1-8; S, spacer; CUB (C1r/C1s, urinary epidermal growth factor, bone morphogenetic protein); SP, signal peptide.

Synonymous variants may affect splicing and miRNA-binding sites within ADAMTS13. (A) ADAMTS13 sSNVs that were predicted to affect splice sites across ADAMTS13 exons and encoded protein domains. Exons are colored consistent with the protein domain(s) they encode. sSNVs that were predicted to affect constitutive donors are highlighted in dark pink, and those predicted to affect constitutive acceptors are highlighted in dark blue. Variants predicted to affect cryptic donors are highlighted in light pink, and those predicted to affect cryptic acceptors are highlighted in light blue. Variants predicted to affect special case exon 8 acceptor or exon 25 donor are colored green. USS variants are shown in red. (B) Variants predicted to affect miRNA-binding sites according to Paccmit-CDS, TargetScan, and miRDB. Consistency of splice affects predictions between MES, NNsplice (NN), SpliceSiteFinder-like (SSF), and GeneSplicer (GS) splice prediction tools for constitutive splice sites (C) and for cryptic and special case cryptic splice sites (D). (E) Venn diagram displays numbers of ADAMTS13 sSNVs that affect miRNA-binding sites as predicted by Paccmit-CDS, TargetScan, and miRDB. Acc, acceptor; C, cysteine-rich; Cryp, cryptic; D, disintegrin-like; Don, donor; M, metalloproteinase; P, propeptide; T1-T8, thrombospondin repeats 1-8; S, spacer; CUB (C1r/C1s, urinary epidermal growth factor, bone morphogenetic protein); SP, signal peptide.

To further validate predictions of splice impact, we used additional tools (SpliceSiteFinder-like and GeneSplicer) for variants predicted to affect splicing by MES or NNsplice. For variants predicted to affect constitutive splice sites, limited agreement was found between the tools used (Figure 5C). However, we found 5 variants predicted to affect cryptic splice sites with complete agreement between 4 splicing tools and 4 additional variants with agreement between 3 splicing tools (Figure 5D).

Because ADAMTS13 sSNVs may affect miRNA-binding sites and cause translational suppression or protein degradation,69 we next examined variants for their likelihood to affect miRNA-ADAMTS13 binding based on Paccmit-CDS, TargetScan, and miRDB. We found 9 variants predicted to affect miRNA-binding sites by all 3 tools (Figure 5B). These 9 variants resulted in gain of binding sites for 10 different miRNA species and loss of binding sites for 4 miRNA species.

Because TargetScan and miRDB are tools primarily used to assess miRNA binding in 3′UTR, we expected to see some disagreement between these tools and Paccmit-CDS, which was specifically developed to assess miRNA binding to mRNA-coding regions. We found substantially higher overlap between TargetScan and other algorithms when using extended seed (nucleotides 2-8 of the miRNA) rather than nucleotides 1 to 7 as seed sequences (Table 2; supplemental Table 4; supplemental Figure 3); thus, the TargetScan values resulted from using bp 2 to 8 (Figure 5E; Table 2).

Paccmit-CDS predicted gain/loss of 3408 miRNA-binding sites resulting from sSNVs. Of these 3408 affected miRNA-binding sites, 14 were predicted by TargetScan and miRDB (Figure 5B; Table 2), and 186 were predicted by TargetScan (Figure 5E). From these predicted miRNAs, miR-221-5p and miR-1248 were shown to be expressed in liver cells,70,71 where ADAMTS13 is predominantly expressed.72 Further confirming its relevance to the liver, miR-221 displayed upregulation in liver fibrosis73 and promoted human hepatocellular carcinoma migration.74

Some sSNVs significantly affect the codon usage bias

We next evaluated how sSNVs could change ADAMTS13 synonymous codon preference. Here, P values <.05 were considered significant.

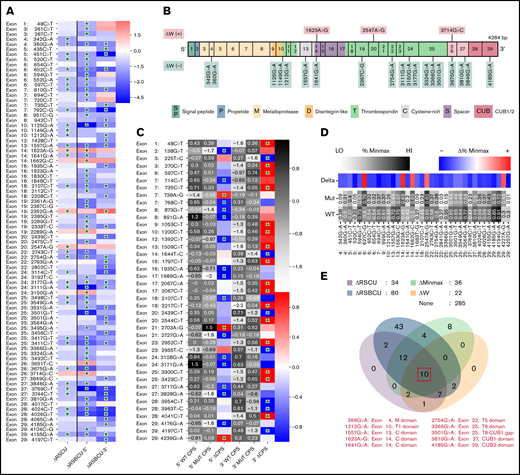

A total of 83 sSNVs exhibited significantly different codon usage or codon pair usage based on RSCU and RSBCU values, respectively (Figure 6A; supplemental Figure 4). From this group, 22 sSNVs displayed significantly different codon adaptation index (ΔW) (Figure 6B). ADAMTS13 sSNVs commonly inserted RCs (supplemental Table 5), which are expected to decrease translation rate. Among them, variants c.360G>A, c.451C>T, c.1125G>A, c.1557G>A, c.2754G>A, c.3501G>A, c.3810C>A, and c.4185G>A led to decreases in codon usage metrics. Only 7 synonymous variants significantly increased indices of codon usage (supplemental Figure 4).

Synonymous variants of ADAMTS13 affect codon usage. (A) Synonymous ADAMTS13 variants with significantly different RSCU (ΔRSCU) or relative synonymous bicodon usage for 2 codon pairs (ΔRSBCU-5′ and ΔRSBCU-3′) compared with WT ADAMT S13. Green stars indicate significant values. (B) sSNVs with significantly different codon adaptation index (ΔW). (C) Variants with significant changes in CPS for 5′ or for 3′ codon pair. Green stars indicate whether change in CPS is significant for each variant and each codon pair. (D) Variants that result in significantly different %MinMax values. All δ values presented here are significant. (E) Overlap between variants that significantly affect ΔRSCU, relative synonymous bicodon usage ΔRS BCU, Δ%MinMax, and ΔW. Ten sSNVs that significantly affect all 4 parameters appear in red along with their exon and encoded protein domain. Differences considered significant where P < .05 (see the supplemental Methods for a description of P value computation and supplemental Excel File 1 for P values).

Synonymous variants of ADAMTS13 affect codon usage. (A) Synonymous ADAMTS13 variants with significantly different RSCU (ΔRSCU) or relative synonymous bicodon usage for 2 codon pairs (ΔRSBCU-5′ and ΔRSBCU-3′) compared with WT ADAMT S13. Green stars indicate significant values. (B) sSNVs with significantly different codon adaptation index (ΔW). (C) Variants with significant changes in CPS for 5′ or for 3′ codon pair. Green stars indicate whether change in CPS is significant for each variant and each codon pair. (D) Variants that result in significantly different %MinMax values. All δ values presented here are significant. (E) Overlap between variants that significantly affect ΔRSCU, relative synonymous bicodon usage ΔRS BCU, Δ%MinMax, and ΔW. Ten sSNVs that significantly affect all 4 parameters appear in red along with their exon and encoded protein domain. Differences considered significant where P < .05 (see the supplemental Methods for a description of P value computation and supplemental Excel File 1 for P values).

We also calculated changes in CPS for sSNVs of ADAMTS13 to measure the impact of codon pair usage while controlling for codon usage. Forty-one sSNVs exhibited significantly different CPS values (Figure 6C). Three sSNVs (c.138G>T, c.225 T>C, and c.1989G>A) exhibited the largest decrease in CPS values. Only two sSNVs (c.738A>G and c.2703A>G) resulted in increased CPS for both affected codon pairs, although the increase was only significant for the 5′ codon pair. As expected, ΔRSCU showed a strong linear correlation with Δ%MinMax (supplemental Figure 5A), and we found a stronger correlation between CPS and RSBCU for 3′ codon pair than 5′ codon pair (supplemental Figure 5B-C). Next, we computed rare and common codon clustering for ADAMTS13 sSNVs using %MinMax.75 Of these, 31 variants resulted in significantly decreased %MinMax, and 5 resulted in significantly increased %MinMax (Figure 6D). Variants that decrease %MinMax imply the insertion of RCs, which can reduce local translation rate75 ; variants that increase %MinMax imply the loss of RCs, which may be necessary for proper cotranslational folding.76

In addition, we investigated RC enrichment at positions of ADAMTS13 sSNVs and identified several loci with significant RC enrichment (supplemental Figure 6). RCs may inhibit translational initiation or slow translation elongation, which in turn can promote mRNA degradation and even affect protein folding.77 The highest increase in RC values were observed at positions 1551, 2439, 2448, and 3684 in exons 13, 20, 20, and 26, respectively. Synonymous variations in these positions may affect ADAMTS13 translational rate and disturb protein folding.

When comparing variants that significantly affect RSCU, RSBCU, W, and %MinMax, we identified 10 sSNVs located in multiple different exons (Figure 6E) that significantly affect all parameters. We found 3 of these variants also significantly affected RC but we found no sSNVs that also significantly affect CPS (supplemental Figure 7).

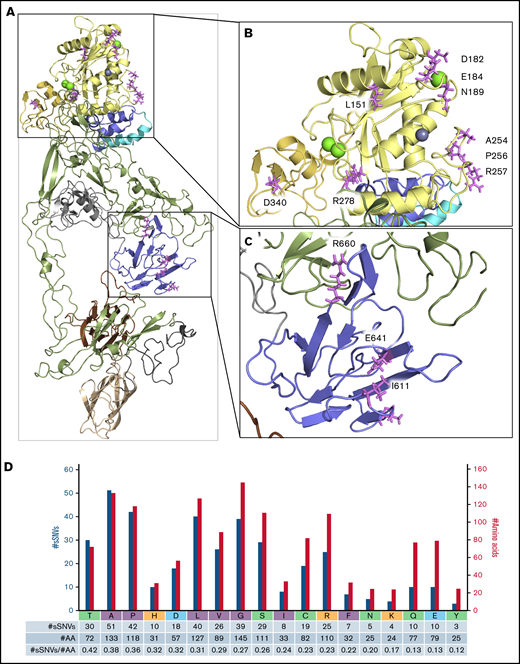

sSNVs may affect mRNA regions encoding the ADAMTS13 active site and metal-binding domains and its protein structure

Next, we investigated the regions essential for ADAMTS13 functionality to assess their vulnerability to sSNVs. Detailed crystal structure evaluation of ADAMT13 proximal domain MDTCS25 compared with identified sSNV positions revealed 13 sSNVs affecting loci critical for metal binding and protein activity (Figure 7A-C; Table 3). C.564C>T affected a codon directly involved in Ca2+ binding (Figure 7B). Another variant, c.1980G>A, is localized within the loop 660-672 that is essential in interaction with VWF78,79 and/or CUB domains relevant to “closed” ADAMTS13 conformation (Figure 7C).80

ADAMTS13 sSNVs may affect mRNA regions encoding the active site and metal-binding domains. Crystal structure of the ADAMT S13 domain (A) with the highlighted metalloprotease domain (B) and spacer domain (C) to display amino acid (AA) position that may be affected by synonymous variants of ADAMT S13. Specific ADAMT S13 domains are color coded: signal peptide = light blue; propeptide = blue; metalloprotease = yellow; disintegrin-like = gold; T1-T8 = green; C = cysteine-rich = gray; spacer = purple; CUB1 = ivory; and CUB2 = brown. (D) Number of ADAMT S13 sSNVs encoding specific amino acids (nonpolar in gray, polar in green, positively charged in red, negatively charged in blue) represented by blue bars and the number of each amino acid in ADAMT S13 represented by gold bars.

ADAMTS13 sSNVs may affect mRNA regions encoding the active site and metal-binding domains. Crystal structure of the ADAMT S13 domain (A) with the highlighted metalloprotease domain (B) and spacer domain (C) to display amino acid (AA) position that may be affected by synonymous variants of ADAMT S13. Specific ADAMT S13 domains are color coded: signal peptide = light blue; propeptide = blue; metalloprotease = yellow; disintegrin-like = gold; T1-T8 = green; C = cysteine-rich = gray; spacer = purple; CUB1 = ivory; and CUB2 = brown. (D) Number of ADAMT S13 sSNVs encoding specific amino acids (nonpolar in gray, polar in green, positively charged in red, negatively charged in blue) represented by blue bars and the number of each amino acid in ADAMT S13 represented by gold bars.

Nevertheless, 4 of these 13 sSNVs were predicted to affect mRNA splicing: c.546C>T, c.552G>A, c.567C>T, and c.834G>T (Figure 5A). Two were predicted to affect miRNA-binding sites: c.1833C>T and c.1980G>A (Table 2). Two variants significantly affected mRNA folding energy (supplemental Figure 8A).

CUB1 domain amino acids Cys1254 and Cys1275 are essential for proper secretion and proteolytic activity of ADAMTS13,81 suggesting relevance of c.3762C>T and c.3825C>T variants. Furthermore, 16 additional sSNVs were identified in codons encoding cysteine, whose disulfide bonds stabilize the overall structure of ADAMTS13, and 42 sSNVs were identified in codons encoding proline, which introduces rigid turns into the peptide chain and sets α‐helix and β-sheet borders.82 Because proline and cysteine substantially influence protein structure, we expect more severe consequences from variants affecting proline or cysteine codons than from variants affecting other codons. Variants affecting cysteine codons did not significantly influence mRNA stability or codon usage (supplemental Figure 8B). Interestingly, based on amino acid frequency in ADAMTS13, neutral sSNVs affecting cysteine codons were 15% less frequent than expected (supplemental Table 6).

Proline codons, in addition to those encoding alanine and threonine, were among the most frequently affected codons by sSNVs of ADAMTS13 (Figure 7D; supplemental Table 6). Proline codons are often affected by sSNVs in signal peptide, propeptide, and disintegrin-like domains (supplemental Figure 9). Several variants affecting proline codons were predicted to influence other examined parameters (supplemental Figure 8C). Seven variants may affect splicing (Figure 6), and 2 may affect miRNA binding (Table 2).

In addition, threonine, alanine, and proline codons were more commontly affected by ADAMTS13 sSNVs, whereas tyrosine codons were less commonly affected by sSNVs than was expected (supplemental Table 6; supplemental Figure 9). Synonymous mutation in leucine codons dominate in metalloprotease and CUB domains, whereas sSNVs in neutral alanine codons were seen most frequently in thrombospondin domains. USS variants mostly encode leucine valine and serine codons (Figure 7D; supplemental Figure 9H).

Finally, because changes in translation kinetics may affect cotranslational folding, we calculated ADAMTS13 folding energy of the nascent protein chain. We identified three variants (c.3150G>A, c.3177G>A, and c.2338T>C) downstream from areas of large changes in cotranslational folding energy (Table 4) and which change RSCU or RSBCU. Together, this implies these variants have the greatest potential impact on protein secondary structure.

Discussion

Although most identified ADAMTS13 sSNVs are very rare, common sSNVs mainly coexist as haplotypes, making it very challenging to find individuals with a single sSNV to evaluate its effect. Conversely, cost and complexity remain substantial obstacles for comprehensive characterization of sSNVs affecting protein properties and disease states in vitro. Our in silico analysis of biomolecular characteristics of ADAMTS13 reveals a powerful opportunity for high-throughput screening of sSNVs likely to affect protein properties, even for large complex genes such as ADAMTS13. By integrating findings from a variety of in silico tools assessing different characteristics, we can comprehensively assess multiple mechanisms by which sSNVs may exert a biological impact. Results in the current study focus on ADAMTS13 sSNVs, but our approach using in silico tools to assess several different biomolecular mechanisms is generalizable to any gene.

The estimated heritability of ADAMTS13 antigen levels suggests that most of the population variance of plasma ADAMTS13 is the result of genetic factors,38,39 including sSNVs. Our findings suggest numerous synonymous variants that may affect ADAMTS13 properties through multiple mechanisms, including pre-mRNA splicing, miRNA silencing, and translation kinetics.

Although there is no single ADAMTS13 sSNV known to be responsible for USS, there are few documented examples in the literature that associate sSNVs of ADAMTS13 to pathologic states. In addition to USS variants (supplemental Table 1), other sSNVs has been identified and clinically evaluated (supplemental Table 7). Most of the sSNVs identified in patients with TTP have been labeled as haplotype with other synonymous variants that are associated with the disease,15,30,83 , -87 and thus it is difficult to evaluate the role of sSNVs in these individuals.

The genotype analysis of ADAMTS13 in 14 neonates diagnosed with congenital heart disease (CHD)83 identified 4 patients with thrombosis and 10 patients without thrombosis (supplemental Table 8).83 One patient (patient 2) who developed thrombosis at the site of surgery has ADAMTS13 haplotype with 3 sSNVs (c.420T>C [rs3118667], 1716G>A [rs372789831], c.2280T>C [rs3124767]), one not-TTP variant (c.2699C>T, rs685523), and one TPP variant (c.1370C>T, rs36220240) and was asymptomatic despite the presence of deleterious mutation previously linked to congenital TTP (c.1370C>T, rs36220240). Moreover, 10 patients with CHD exhibited high to normal ADAMTS13 antigen and activity levels (∼50%, which is considered the lower normal range in neonates88 ) and have not developed thrombosis, whereas missense mutations (c.1342C>G [rs2301612, p.G448E], c.1370C>T [rs36220240, p.P457L], and c.2699C>T [rs685523, p.A900V]) often identified in patients with TTP29,30,38 were accompanied by sSNV variants. One CHD patient (patient number 7 without thrombosis) had single sSNV: c.2280T>C (rs3124767) in the ADAMTS13 gene and high ADAMTS13 antigen (63.6%) and activity (43.6%) levels. In addition, in vivo evaluation of the ADAMTS13 haplotype seen in patient 2 showed that the deleterious effect seen for the TTP variant (c.1370C>T, rs36220240, p.P457L) can be rescued by synonymous variants (supplemental Table 7).89 These studies suggest that sSNVs identified in neonates may have synergistic protective effects on ADAMTS13 functions. GWAS of plasma ADAMTS13 concentrations from healthy donors showed that individuals with c.420T>C or c.4221C>A variants exhibited ∼6% increase in ADAMTS13, whereas in patients with variants c.1716G>A or c.2280 C>T, the ADAMTS13 level was ∼5% lower. These synonymous variants were shown to alter ADAMTS13 expression and activity levels in in vitro studies (supplemental Tables 7 and 9).10,41 Variant c.420T>C (rs3118667) also exhibited a 3% increase in ADAMTS13 activity by GWAS39 and has been significantly associated with pediatric stroke.90 In addition, c.4221C>A was significantly more frequent in populations with major adverse cardiac events, cerebrovascular events,91 and Thai malaria.92

Overall, although the effect from single sSNVs is not dramatic, coexistence of 2 or more variants may have a synergistic effect and cause significant changes in ADAMTS13 functions.29,89,93 Combined, this evidence suggests that ADAMTS13 sSNVs affect plasma ADAMTS13 antigen and activity levels, emphasizing their relevance to cardiovascular disease and coagulopathy.

In our in silico studies, the sSNVs identified in patient samples (supplemental Table 7) were located within RC-enriched regions (supplemental Table 9). Significantly high RC enrichment would suggest a cluster of conserved RCs around the region, thus amplifying potential impact from changes to more common codons.94 In addition, validation of RNA minimum free energy of full-length ADAMTS13 variants that have been identified in human subjects displayed significant differences in their RNA secondary structure (compared with WT), which may explain district antigen and activity level in those variants (supplemental Figure 2; supplemental Table 2).

To summarize, we have presented a comprehensive in silico overview of all reported ADAMST13 sSNVs that may be used as point of reference to understand the clinical consequences of ADAMTS13 sSNVs. We found numerous sSNVs that affect ADAMTS13 GC content and CpG sites. Several methods were used to evaluate codon and codon pair usage changes that may affect translation rate and cotranslational folding of ADAMTS13. Moreover, our results show that 67 sSNVs confer significantly different mRNA folding energy compared with WT. Next, our analysis revealed 46 sSNVs that may affect ADAMTS13 splicing, including two USS variants, c.936C>T (rs36219562) and c.1797C>T (rs36221216). Nine sSNVs were found that can affect the binding sites of 14 miRNAs. Although the effect of miRNA binding within coding region may not be as high as in 3′UTR, they may still contribute to observed variance in ADAMTS13 expression.95,96

Calculation of cotranslational folding in the nascent protein chain identified 3 variants that may substantially affect protein folding. In addition, we characterized potential effects of these sSNVs on protein structure, especially with respect to the ADAMTS13-active site.

Our previous evaluation of some ADAMTS13 SNVs found that even the variants with moderate changes in ΔG or codon usage can affect protein properties.10 Although further experimental evaluation is needed to fully validate the role of synonymous variation in protein function, this study has identified several ADAMTS13 sSNVs that are most likely to affect ADAMTS13 protein properties.

Deficiency or dysfunction of ADAMTS13 can lead to thrombotic pathologies, including TTP, USS, myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke,18,27,97 and may contribute to COVID-19–associated coagulopathy.20 As we show here, rare synonymous ADAMTS13 variants may markedly contribute to the natural variation observed in the healthy population and might explain differential susceptibility to thrombosis. Most of these ADAMTS13 sSNVs have not been identified in prior GWAS, often being systematically excluded. Better understanding of these sSNVs and appreciating how they contribute to variability in ADAMTS13 abundance and specific activity highlight the broader importance of considering sSNVs when assessing potential causes for differential gene expression, protein abundance, and structure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Aaron Liss, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration (CBER FDA), for his assistance gathering variants from dbSNP.

This work was supported by funds from the CBER FDA operating funds. The work was also funded by CBER FDA special COVID-19 funds.

The findings and conclusions in this article have not been formally disseminated by the FDA and should not be construed as representing any agency determination or policy.

Authorship

Contribution: K.I.J., D.M., and D.D.H. equally contributed to the manuscript and were involved in the in silico analysis, performed data analyses, and participated in writing the manuscript; J.K. performed miRNA analysis; N.H.-K. and R.C.H. assisted in the review and editing of the manuscript; U.K.K., R.C.H., and J.C.I. provided clinical data analysis; and C.K.-S. designed the research plan, oversaw the project, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Chava Kimchi-Sarfaty, US Food and Drug Administration, 10903 New Hampshire Ave, Silver Spring, MD 20993; e-mail: Chava.Kimchi-Sarfaty@fda.hhs.gov.

References

Author notes

K.I.J., D.M., and D.D.H. contributed equally to this study.

For data sharing, contact the corresponding author: Chava.Kimchi-Sarfaty@fda.hhs.gov.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.