Key Points

The lncRNA ELDR inhibits the leukemic potential of AML with MLL-r and enhances the therapeutic effect of ATRA and LSD1 inhibitors.

The lncRNA ELDR exerts its antileukemic effect by inhibiting DNA replication and by reducing chromatin accessibility at centromeres.

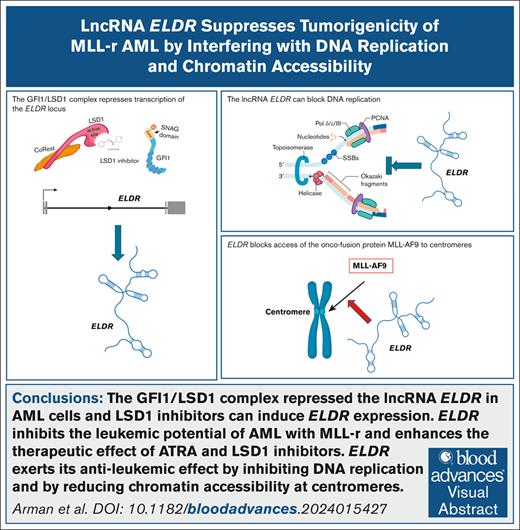

Visual Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with rearrangement of the mixed lineage leukemia gene expresses MLL-AF9 fusion protein, a transcription factor that impairs differentiation and drives expansion of leukemic cells. In this work, the zinc finger protein “growth factor independent 1” together with the histone methyltransferase LSD1 is revealed to occupy the promoter and regulate the expression of the lncRNA ELDR (EGFR [epidermal growth factor receptor] long non-coding downstream RNA) in the rearranged Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) (MLL-r) AML cell line THP-1. Forced ELDR overexpression enhanced the growth inhibition of an Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 inhibitor (LSD1i)/all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) combination treatment and reduced the capacity of these cells to generate leukemia in xenografts, leading to a longer leukemia-free survival. ELDR is found to bind the clamp protein Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) and the MCM5 helicases causing defects of DNA replication fork progression. Moreover, AML cells overexpressing ELDR had reduced chromatin accessibility and transcription at α-satellite repeats in centromeres. In addition, ELDR RNA was detected close to MLL-AF9 at centromeres suggesting that it impedes leukemic progression preferentially of MLL-r AML by interfering with both DNA replication and centromeric transcription. Our findings reveal novel functions of the lncRNA ELDR in DNA replication and centromere biology when expressed at high levels in AML cells with MLL rearrangements. These discoveries could provide rationale for future strategies to treat MLL-r AML, which has a poor prognosis in children and adults. Delivery of the ELDR RNA could potentially be used as an adjunct to LSD1i/ATRA treatment or other currently used chemotherapeutic drugs to develop novel therapies for these AML subtypes.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a blood cancer characterized by malignant myeloid blasts in the bone marrow and blood,1,2 and its treatment consists of chemotherapy, sometimes in combination with drugs that specifically target the molecular defects associated with a particular subtype3 or monoclonal antibodies, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) or Hedgehog inhibitors.4-6 The M5 AML subtype bears translocations affecting the Mixed-Lineage Leukemia (MLL) (KMTA2) locus on chromosome 11, which encodes a lysine methyltransferase.7 In these rearranged MLL (MLL-r) leukemias, the N-terminal DNA-binding part of MLL is fused to partners8,9 such as AF9 (MLLT3) in t(9;11) AML and AF4 (AFF1) in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL).8,10

LSD1 is an epigenetic “eraser” that represses transcription by removing methyl groups from histone H3 lysine 4 at promoters or enhancers.11,12 LSD1 is highly expressed in leukemic blasts across AML subtypes, and LSD1 inhibitors promote blast cell differentiation in MLL-r AML holding promise as therapeutic drugs.13 Furthermore, LSD1 is recruited to target genes associated with cell cycle progression, cell survival, and differentiation by the protein “growth factor independent 1” (GFI1).14,15 GFI1 has C-terminal zinc finger domains mediating DNA binding and an N-terminal, 20 amino acid “SNAG” domain that binds to LSD1.14

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are RNA molecules that do not encode proteins but are otherwise similar to messenger RNAs in structure and synthesis.16 Some lncRNAs have been linked to cancer including AML.17,18 The lncRNA ELDR (EGFR [epidermal growth factor receptor] long non-coding downstream RNA) is located downstream of the EGFR gene on chromosome 7 on the opposite strand19,20 and has been found to affect chromatin accessibility and cellular senescence.21 Deregulation of ELDR expression is found in several solid tumors20 and in chondrocyte senescence and arthritis.21

In this work, ELDR is found to be repressed by the GFI1/LSD1 complex in AML cells and ELDR upregulation is revealed to occur on treatment with LSD1 inhibitors or GFI1 knockdown. Forced ELDR overexpression in THP-1 cells enhanced the growth inhibition of an Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 inhibitor (LSD1i) and all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) combination treatment, both in vitro and in vivo. ELDR expression significantly reduced the capacity of AML cells to generate leukemia xenografts, leading to a longer leukemia-free survival. The observations in this study suggest that these effects are due to the interference of ELDR with DNA replication and chromatin accessibility at centromeres.

Materials and methods

Treatment of cells with drugs

Cells were treated with ATRA (final concentration 11.1 nM, Cedarlane, 11017-1) or LSD1i (final concentration 500 nM, GSK2879552 2HCl, S7796) or ATRA plus LSD1i. As controls, midostaurin (final concentration 250 nM, S8064) and Pinometostat (final concentration 100 nM, S7062) were used.

Trypan blue exclusion assay/viable cell count

On day 0, cells were seeded (in triplicates) in 24-well plates at a concentration of 1.5 × 105 to 2 × 105/600 μL respective media. When indicated, cells were treated with drugs on day 0. Live or viable (trypan blue exclusive) cells were counted using a hemocytometer on day 1 to day 5 (or indicated time points).

All mouse work was reviewed and approved by the animal protection committee at the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montreal (protocol catalog no. 2020-08), according to the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care.

Other methods

The detailed protocols are described in the supplemental Methods.

Results

The lncRNA ELDR is regulated by GFI1/LSD1 and impedes growth of AML cells

Interrogation of chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data from THP-1 AML cells,22 which represent a pediatric M5 AML with a t(9:11) translocation, for GFI1 target genes revealed a peak at the 5′ end of the gene encoding the lncRNA ELDR (Figure 1A-B). LSD1 was also recruited to the ELDR promoter, and a treatment with the LSD1 inhibitor OG86 evicted GFI1 and LSD1 from this site (Figure 1C).22,23 ChIP-quantitative polymerase chain reaction confirmed enrichment of GFI1 near the ELDR promoter (Figure 1D). Treatment with the LSD1 inhibitor GSK2879552 or knockdown of GFI1 caused an almost threefold upregulation of ELDR in THP-1 cells (Figure 1E-F). The increased endogenous ELDR expression in LSD1i-treated THP-1 cells was not associated with a general increase of the neighboring genes (Figure 1G). In addition, forced expression of GFI1 reduced ELDR expression in mouse RAW 264.7 cells, which express relatively high levels of ELDR compared with THP-1 cells (Figure 1H). Moreover, data from the Bloodspot database revealed that high expression of GFI1 correlated with very low expression of ELDR in different categories (supplemental Figure 1A), suggesting a direct regulation of ELDR expression by the GFI1/LSD1 complex.

Stable ELDR was then established overexpressing THP-1 and Mono-Mac-1 cell lines, which both represent an M5 AML subtype with t(9;11) translocation (Figure 1I-J). This ectopic overexpression of ELDR did not affect genes located in the vicinity of the endogenous ELDR locus (±200 kb) (Figure 1K), excluding a trans effect. Compared with established ELDR-overexpressing lines, the endogenous expression of ELDR in THP-1 cells and a series of other AML cell lines was very low regardless of the MLL-r status (Figure 1L). Established ELDR-overexpressing cell lines demonstrated significantly slower growth than control cell lines, in particular when the cells were grown in HS-5 conditioned media24 (Figure 2A-D). Other M5 MLL-r AML lines, but also the erythroleukemia line KG-1a, demonstrated a similar growth inhibition with ELDR overexpression in HS-5 conditioned medium (supplemental Figure 1B-F; supplemental Table 1). In contrast, Kasumi-1 cells, derived from a pediatric M2 AML, did not demonstrate growth inhibition on ELDR overexpression (supplemental Figure 2A-B), although the ELDR promotor was occupied by GFI1 (supplemental Figure 2C-D), suggesting that ELDR may specifically act in M5 AML with MLL translocations.

ELDR overexpression affects growth and cell cycle progression. (A-B) ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 lines ELDR-C1, ELDR-C3 and ELDR-overexpressing Mono-Mac-1 lines ELDR-C5 and ELDR-C7 reveal delayed growth measured by trypan blue exclusion when cultured in normal media (NM) compared with control cell lines established by transfection with EV controls. n = 3 biological replicates. (C-D) Growth curves of the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell line (ELDR-C1) or EV control (EV1) and ELDR-overexpressing Mono-Mac-1 cell line (ELDR-C7) or EV control (EV2) in HS-5 conditioned media. n = 3 biological replicates. (E) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) plots revealing EdU incorporation (y-axis) and DAPI staining (x-axis) of cells from the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell line (ELDR-C1) or the EV control cell line (EV1) and ELDR-overexpressing Mono-Mac-1 cell line (ELDR-C7), or EV control (EV2) grown in HS-5 conditioned media. Cell cycle phase gates and percentage of cells in each gate are indicated on the plot. (F-G) Quantification of cells in G1, S, or G2/M phase of the indicated cell lines grown in NM or HS-5 conditioned media. n = 3 biological replicates. (H) Quantification of cells in G1, S, or G2/M phase from the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell line (ELDR-C1ctrl) or the EV control cell line (EV1ctrl) vs ELDR deleted cell lines ELDR-C1del ELDR or EV1del ELDR grown in HS-5 conditioned media (del ELDR: CRISPR/Cas9 with gRNAs specific to ELDR; ctrl: CRISPR/Cas9 with nontargeting gRNAs). n = 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (statistical analysis: EV1 vs ELDR-C1, ELDR-C3 for THP1, EV2 vs ELDR-C5, ELDR-C7 for Mono-Mac-1) (panels A-B); parametric unpaired t test (panels C-D); 1-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's for multiple comparisons test (panels F-H). ns, not significant.

ELDR overexpression affects growth and cell cycle progression. (A-B) ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 lines ELDR-C1, ELDR-C3 and ELDR-overexpressing Mono-Mac-1 lines ELDR-C5 and ELDR-C7 reveal delayed growth measured by trypan blue exclusion when cultured in normal media (NM) compared with control cell lines established by transfection with EV controls. n = 3 biological replicates. (C-D) Growth curves of the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell line (ELDR-C1) or EV control (EV1) and ELDR-overexpressing Mono-Mac-1 cell line (ELDR-C7) or EV control (EV2) in HS-5 conditioned media. n = 3 biological replicates. (E) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) plots revealing EdU incorporation (y-axis) and DAPI staining (x-axis) of cells from the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell line (ELDR-C1) or the EV control cell line (EV1) and ELDR-overexpressing Mono-Mac-1 cell line (ELDR-C7), or EV control (EV2) grown in HS-5 conditioned media. Cell cycle phase gates and percentage of cells in each gate are indicated on the plot. (F-G) Quantification of cells in G1, S, or G2/M phase of the indicated cell lines grown in NM or HS-5 conditioned media. n = 3 biological replicates. (H) Quantification of cells in G1, S, or G2/M phase from the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell line (ELDR-C1ctrl) or the EV control cell line (EV1ctrl) vs ELDR deleted cell lines ELDR-C1del ELDR or EV1del ELDR grown in HS-5 conditioned media (del ELDR: CRISPR/Cas9 with gRNAs specific to ELDR; ctrl: CRISPR/Cas9 with nontargeting gRNAs). n = 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (statistical analysis: EV1 vs ELDR-C1, ELDR-C3 for THP1, EV2 vs ELDR-C5, ELDR-C7 for Mono-Mac-1) (panels A-B); parametric unpaired t test (panels C-D); 1-way ANOVA with Holm-Šídák's for multiple comparisons test (panels F-H). ns, not significant.

ELDR slows down S phase progression and induces differentiation

ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 lines (ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3) had significantly less viable cells compared with controls (supplemental Figure 2E), but a staining with Annexin V and propidium iodide did not reveal dead or apoptotic cells (supplemental Figure 2F). ELDR affected cell cycle progression of THP-1 and Mono-Mac-1 cell lines most significantly when cultured in HS-5 conditioned media (Figure 2E-G; supplemental Figure 2G-H). Under these conditions, they accumulated in G1 and in G2/M phase and had decreased numbers of cells in S phase compared with Empty Vector (EV) controls, suggesting that ELDR arrests cells in G1 and G2/M phases and compromises entry into the S phase. The cell cycle defects of ELDR-overexpressing THP1 cells were not accompanied by altered expression of regulators of cell cycle progression or apoptosis (supplemental Figure 3A-E).

To validate the functionality of the ectopic ELDR allele, CRISPR/Cas9 expressing lentiviruses to knockout ELDR in the established ELDR-C1 cell line were used. The cells were named as ELDR-C1delELDR and EV1delELDR for groups treated with guide RNAs (gRNAs) specific to ELDR and ELDR-C1ctrl and as EV1ctrl to groups treated with nontargeting control gRNAs. Loss of ELDR expression was confirmed by RT-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (supplemental Figure 3F). Compared with the control cell line EV1ctrl, ELDR-C1delELDR cells no longer demonstrated increased number of cells in G1 or G2/M phase and decreased number of cells in S phase (Figure 2H).

ELDR expressing THP-1 cells demonstrated altered morphology indicating differentiation, which was enhanced by treatment with ATRA (Figure 3A-B; supplemental Figure 3G), which can drive differentiation.25,26 It is known that LSD1 inhibitors reduce growth and induce differentiation of AML cells, and that this effect is potentiated by ATRA.12,27-29 Consistently, compared with controls, ELDR-overexpressing cell lines demonstrated morphological differentiation with upregulation of the differentiation marker CD11b (ITGAM or MAC-1) when treated with ATRA or LSD1i or both (Figure 3C-E; supplemental Table 2). This upregulation of CD11b was reversed in cells where the ectopic ELDR was again deleted (ELDR-C1delELDR) compared with controls (EV1ctrl) (supplemental Figure 3H). LSD1i or ATRA reduced proliferation of ELDR-overexpressing cell lines compared with controls (Figure 3F-H; supplemental Figure 3I), but they were not affected by FLT3 or DOT1L inhibitors (Figure 3I-J), suggesting that ELDR confers a specific sensitivity to LSD1i and ATRA.

ELDR overexpression induces differentiation of THP-1 cells and renders them sensitive to LSD1i/ATRA. (A) Microscopic images of cells from the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 after treatment with ATRA or vehicle (EtOH) compared with an EV1ctrl after May Grünwald Giemsa staining. The arrows indicate more differentiated cells. (B) Quantification of 3 independent replicates of experiment as described in panel (A) after May Grünwald Giemsa staining. (C-D) CD11b levels (MFI [mean fluorescence intensity] by flow cytometry) measured after 3 days of incubation of ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 and the EV1 line with increasing concentrations of ATRA (C) or 10 nM ATRA and increasing concentrations of LSD1i (D). (E) CD11b EC50 values for MFI of the experiments in panels (C-D). (F-H) Growth curves of the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 in the presence of LSD1i, ATRA, or both. n = 3 biological replicates. The growth curve for EV1 is also revealed as a reference. (I-J) Growth of ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 THP-1 lines compared with the EV1 control in the presence of the indicated inhibitors midostaurin (FLT3 inhibitor) and pinometostat (DOT1L inhibitor). n = 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean + SD (panel B); ± SD (panels C-D, F-J). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (panel B); 2-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (panels C-D); parametric unpaired t test (panels F-J). EtOH, ethanol; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; EV1, empty vector 1; LSD1i, lysine specific demethylase 1 inhibitor; FLT3, Fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 3; DOT1L, DOT1 like histone lysine methyltransferase; ns, not significant.

ELDR overexpression induces differentiation of THP-1 cells and renders them sensitive to LSD1i/ATRA. (A) Microscopic images of cells from the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 after treatment with ATRA or vehicle (EtOH) compared with an EV1ctrl after May Grünwald Giemsa staining. The arrows indicate more differentiated cells. (B) Quantification of 3 independent replicates of experiment as described in panel (A) after May Grünwald Giemsa staining. (C-D) CD11b levels (MFI [mean fluorescence intensity] by flow cytometry) measured after 3 days of incubation of ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 and the EV1 line with increasing concentrations of ATRA (C) or 10 nM ATRA and increasing concentrations of LSD1i (D). (E) CD11b EC50 values for MFI of the experiments in panels (C-D). (F-H) Growth curves of the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 in the presence of LSD1i, ATRA, or both. n = 3 biological replicates. The growth curve for EV1 is also revealed as a reference. (I-J) Growth of ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 THP-1 lines compared with the EV1 control in the presence of the indicated inhibitors midostaurin (FLT3 inhibitor) and pinometostat (DOT1L inhibitor). n = 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean + SD (panel B); ± SD (panels C-D, F-J). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (panel B); 2-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (panels C-D); parametric unpaired t test (panels F-J). EtOH, ethanol; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; EV1, empty vector 1; LSD1i, lysine specific demethylase 1 inhibitor; FLT3, Fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 3; DOT1L, DOT1 like histone lysine methyltransferase; ns, not significant.

The tumorigenicity of AML xenografts is significantly reduced by ELDR

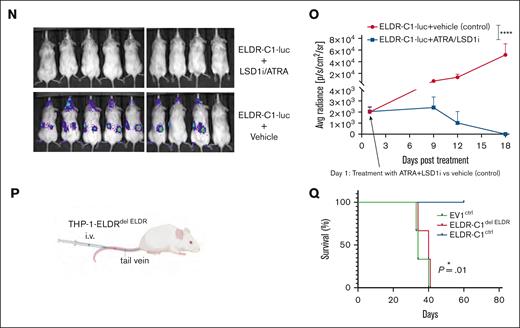

ELDR-overexpressing lines (ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3) generated tumors with smaller volume or lower weight when injected into NSG mice subcutaneously and resulted in reduced organ dissemination when injected IV (Figure 4A-E; supplemental Figure 4A-D). In addition, injected mice demonstrated increased survival compared with controls (Figure 4F). Tumors that emerged after subcutaneous or IV injection of ELDR-overexpressing lines maintained elevated expression of ELDR (supplemental Figure 4E-F). Similar results were obtained with the ELDR-overexpressing Mono-Mac-1 on IV injection in NSG mice (Figure 4G-I; supplemental Figure 4G-I).

Next, a vector for a luciferase reporter gene was introduced into ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cells or EV control cell lines, and lines with comparable luciferase expression were injected IV into NSG mice (supplemental Figure 4J). Mice injected with ELDR-overexpressing cells demonstrated significantly less dissemination of leukemic cells and survived significantly longer (Figure 4J-M). When these animals were also treated with LSD1i/ATRA, they were still leukemia free 18 days after the onset of treatment, whereas control animals had clear signs of leukemic dissemination (Figure 4N-O). When mice were injected with the ELDR-C1delELDR, where the ectopic ELDR was deleted, they died again as fast as animals injected with the control cell line EV1ctrl (Figure 4P-Q). However, animals injected with ELDR-C1ctrl cells that maintained ELDR overexpression survived >60 days (Figure 4P-Q). This suggests that forced expression of ELDR lowers the ability of leukemic cells to engraft and expand in a transplanted host and renders them more sensitive to LSD1i and ATRA.

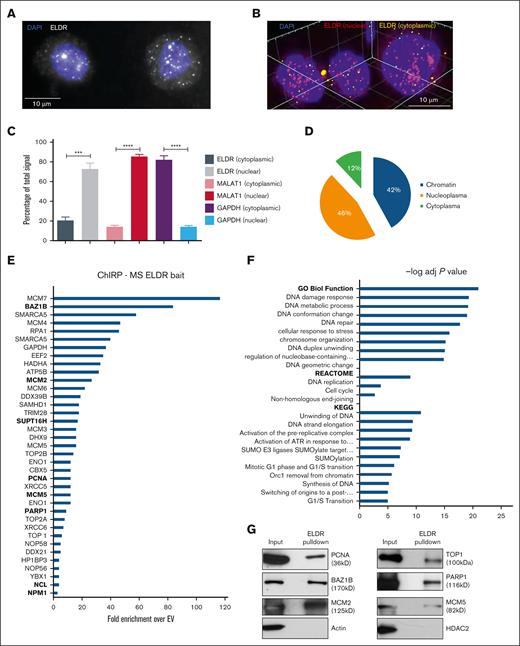

ELDR localizes in the nucleus with chromatin remodeling and DNA replication factors

Single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) and cell fractionation demonstrated a predominantly nuclear localization of ELDR (Figure 5A-D; supplemental Figure 5A). Comprehensive identification of RNA binding proteins by mass spectrometry (ChIRP-MS) was then used to identify binding partners of ELDR following published protocols.31 The specific enrichment for ELDR over input was ∼12% compared with controls (supplemental Figure 5B). The precipitates were subjected to LC/MS-MS for identification of proteins associated with ELDR and curated by eliminating previously defined contaminants of MS experiments32 and metabolic enzymes that contain biotin. Proteins were ranked according to the extent of coverage given by the number of peptides obtained (Figure 5E; supplemental Table 3). Gene ontology analyses revealed that ELDR interacting proteins fall into categories such as DNA damage, DNA strand elongation, DNA replication, cell cycle progression, and chromatin organization (Figure 5F). Several of these protein interactions were validated by ChIRP followed by immunoblotting and conversely by RNA immunoprecipitation assay (Figure 5G-H; supplemental Figure 5C).

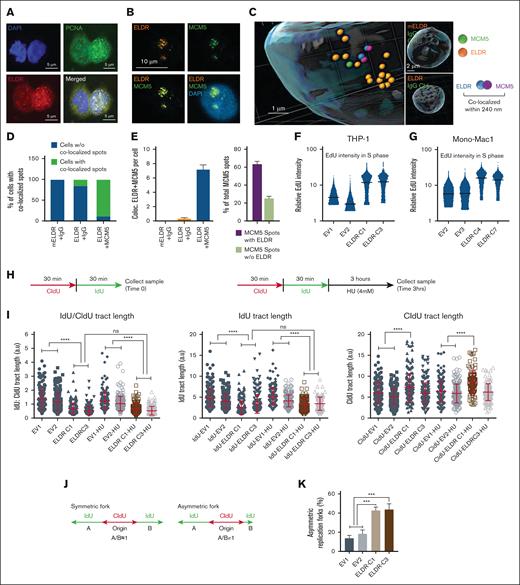

ELDR interferes with DNA replication

The DNA replication clamp processing protein Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) and the DNA helicase MCM5 both interact with ELDR and smFISH, and immunostaining revealed a clear nuclear colocalization of ELDR with these proteins (Figure 6A-B). Spot detection using the IMARIS image software after 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of z-stack acquisitions and quantification revealed that many MCM5 molecules are bound to ELDR (Figure 6C-D) with ∼7 to 8 colocalized ELDR/MCM5 spots per cell and >60% of total MCM5 spots colocalized with ELDR (Figure 6E). A quantification of EdU/DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining of the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 and Mono-Mac-1 cell lines revealed a significant increase of EdU intensity in S phase cells but no changes in Replication Protein A (RPA) loading or γ-H2AX (Figure 6F-G; supplemental Figure 5D-E) suggesting a defect in DNA replication.

ELDR interferes with the progression of DNA replication forks. (A) Representative image of colocalization of ELDR (red) and PCNA (green) in nuclear punctate structures using smFISH for ELDR and immunofluorescence with an anti-PCNA antibody and DAPI staining (blue). Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Representative image of colocalization of ELDR (red) and MCM5 (green) in nuclear punctate structures using smFISH for ELDR and immunofluorescence with an anti-MCM5 antibody and DAPI staining (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Spot detection using the IMARIS software for 3D reconstructions from immunofluorescence images for MCM5 and smFISH for ELDR detection. Spots represent individual signals for MCM5 (green) or ELDR (orange), respectively, and for MCM5-ELDR complexes (blue/purple). The cutoff for colocalization was 240 nm. Scale bar, 1 μm. Controls: representative 3D reconstruction of nuclei stained with an immunoglobulin G (IgG) control antibody and with human ELDR or murine ELDR (mELDR) probes for the smFISH. (D) Quantification of the percentage of cells among all analyzed cells with MCM5-ELDR complexes (ie, colocalized MCM5-ELDR spots per cell). Cell numbers were n = 94 for mELDR + IgG control, n = 63 cells for ELDR + IgG control, n = 109 for ELDR+MCM5. (E) Among cells with ELDR-MCM5 complexes, the number of colocalized spots per cell and the percentage of MCM5 colocalized with and without ELDR were quantified. (F-G) Relative EdU intensity measured by flow cytometry in S phase cells (see gating in Figure 2E) in THP-1 ELDR-overexpressing ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 cell lines compared with control cell lines EV1 and EV2 or in Mono-Mac-1 ELDR-overexpressing ELDR-C4 and ELDR-C7 cell lines compared with control cell lines EV2 and EV3, cultured in HS-5 conditioned media. (H) Left panel: schema of DNA fiber assay. Labeling scheme: CIdU (red) was incorporated as the first analog, followed by IdU (green), incorporated as the second analog at indicated time points. Right panel: HU was added to completely stop fork progression for indicated time point. (I) DNA fiber assay with same incubation times (30 minutes) for IdU and CIdU labeling with or without subsequent HU treatment. Plots of IdU/CIdU ratios and IdU or CIdU track lengths for the indicated THP-1 ELDR-overexpressing cell lines (ELDR-C1, ELDR-C3) and controls (EV1, EV2). Experiments were performed in 2 to 3 biological replicates and at least 150 to 200 dually labeled fibers were measured for each condition. Only bicolor fibers were analyzed, that is, forks that progressed normally during the first labeling period. (J) Schema of symmetric and asymmetric forks. In contrary to symmetric fork progression (A/B ≈ 1), both sides (A and B) of the origin will not progress at the same rate (A/B ≠ 1) in asymmetric fork resulting in fork stalling. (K) Quantification of frequency of asymmetric DNA replication forks (in percent). Total number of forks counted: 30 to 40 per sample. n = 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean + SD (panels E, K); ± SD (panel I). ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using Kruskal-Wallis test (panel I); 1-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test (K). ns, not significant; HU, hydroxyurea.

ELDR interferes with the progression of DNA replication forks. (A) Representative image of colocalization of ELDR (red) and PCNA (green) in nuclear punctate structures using smFISH for ELDR and immunofluorescence with an anti-PCNA antibody and DAPI staining (blue). Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Representative image of colocalization of ELDR (red) and MCM5 (green) in nuclear punctate structures using smFISH for ELDR and immunofluorescence with an anti-MCM5 antibody and DAPI staining (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Spot detection using the IMARIS software for 3D reconstructions from immunofluorescence images for MCM5 and smFISH for ELDR detection. Spots represent individual signals for MCM5 (green) or ELDR (orange), respectively, and for MCM5-ELDR complexes (blue/purple). The cutoff for colocalization was 240 nm. Scale bar, 1 μm. Controls: representative 3D reconstruction of nuclei stained with an immunoglobulin G (IgG) control antibody and with human ELDR or murine ELDR (mELDR) probes for the smFISH. (D) Quantification of the percentage of cells among all analyzed cells with MCM5-ELDR complexes (ie, colocalized MCM5-ELDR spots per cell). Cell numbers were n = 94 for mELDR + IgG control, n = 63 cells for ELDR + IgG control, n = 109 for ELDR+MCM5. (E) Among cells with ELDR-MCM5 complexes, the number of colocalized spots per cell and the percentage of MCM5 colocalized with and without ELDR were quantified. (F-G) Relative EdU intensity measured by flow cytometry in S phase cells (see gating in Figure 2E) in THP-1 ELDR-overexpressing ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 cell lines compared with control cell lines EV1 and EV2 or in Mono-Mac-1 ELDR-overexpressing ELDR-C4 and ELDR-C7 cell lines compared with control cell lines EV2 and EV3, cultured in HS-5 conditioned media. (H) Left panel: schema of DNA fiber assay. Labeling scheme: CIdU (red) was incorporated as the first analog, followed by IdU (green), incorporated as the second analog at indicated time points. Right panel: HU was added to completely stop fork progression for indicated time point. (I) DNA fiber assay with same incubation times (30 minutes) for IdU and CIdU labeling with or without subsequent HU treatment. Plots of IdU/CIdU ratios and IdU or CIdU track lengths for the indicated THP-1 ELDR-overexpressing cell lines (ELDR-C1, ELDR-C3) and controls (EV1, EV2). Experiments were performed in 2 to 3 biological replicates and at least 150 to 200 dually labeled fibers were measured for each condition. Only bicolor fibers were analyzed, that is, forks that progressed normally during the first labeling period. (J) Schema of symmetric and asymmetric forks. In contrary to symmetric fork progression (A/B ≈ 1), both sides (A and B) of the origin will not progress at the same rate (A/B ≠ 1) in asymmetric fork resulting in fork stalling. (K) Quantification of frequency of asymmetric DNA replication forks (in percent). Total number of forks counted: 30 to 40 per sample. n = 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean + SD (panels E, K); ± SD (panel I). ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using Kruskal-Wallis test (panel I); 1-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test (K). ns, not significant; HU, hydroxyurea.

This prompted the use of DNA fiber assays to evaluate the impact of ELDR overexpression on DNA replication dynamics. In this assay, nucleotide analogs (red, chlorodeoxyuridine [CldU]; green, iododeoxyuridine [IdU]) are incorporated into actively replicating DNA to track the progression of DNA replication forks (Figure 6H). Analysis of progressing forks (bicolor) revealed that control cells (EV1, EV2) display a ratio of IdU/CldU of ∼1, whereas ELDR-overexpressing cell lines (ELDR-C1, ELDR-C3) had ratios <1 (Figure 6I). This suggests that either the second label (IdU) is degraded during the experiment or that replication forks stall spontaneously during the second labeling period. Importantly, the analysis of bicolor fibers (actively progressing unidirectional replication forks) might explain why, in contrast to IdU, the length of CldU-labeled DNA is not reduced (Figure 6I).

Nascent DNA can be degraded by nucleases on replication fork stalling in certain pathological situations, for example, in cells lacking BRCA2.33 To test whether overexpression of ELDR causes the degradation of nascent DNA at stalled replication forks, the cells were labeled for 30 minutes with CldU, followed by 30 minutes of IdU, where hydroxyurea (HU) was added to the medium to stop fork progression. The cells were then incubated in HU-containing medium for 3 hours (Figure 6H). Reduction in the ratio of IdU/CldU during HU incubation would indicate that nascent DNA labeled with IdU was degraded, which could not be detected (Figure 6I), indicating that nascent DNA is not degraded by nuclease during HU-induced fork stalling.

Spontaneous replication fork stalling is expected to increase the frequency of “asymmetric” origins in which progression of forks emanating from both sides of a replication origin is different (Figure 6J). In this situation, labeling on both sides of the origin would be of different length, which may reflect fork stalling in one direction. Interestingly, a significant increase of asymmetric forks in ELDR-overexpressing lines compared with controls was observed (Figure 6K), suggesting that ELDR elevates the frequency of spontaneous replication fork stalling.

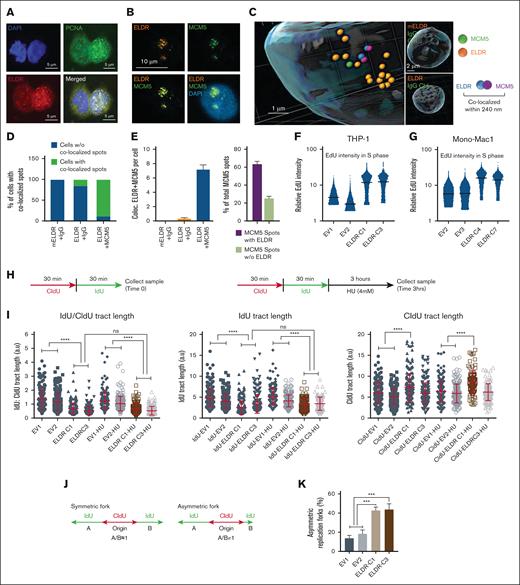

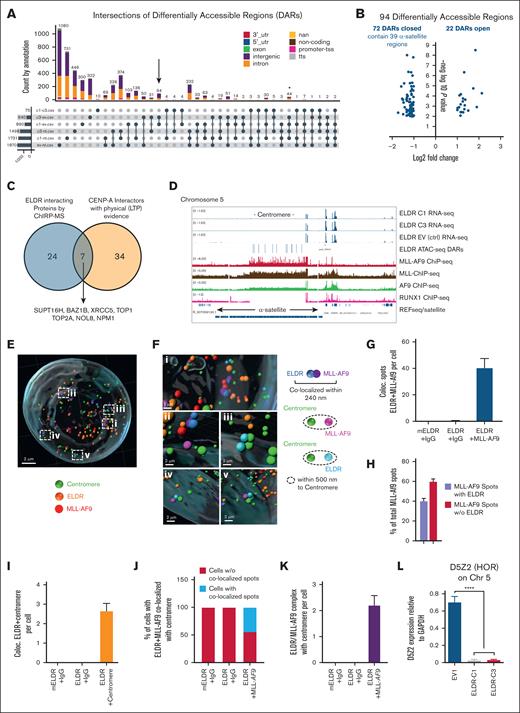

ELDR alters chromatin accessibility in THP-1 cells

Several proteins associated with ELDR, such as BAZ1B and SUPT16H, also function as chromatin remodelers (Figure 5E-H; supplemental Table 3). To test whether ELDR alters chromatin accessibility through association with these proteins, the ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 and EV1 control cell lines and nontransfected (NT) THP-1 cells were used to perform ATAC-seq (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing).34 Principal component analysis revealed that samples segregated in accordance with their experimental group (supplemental Figure 5F). The analysis of specific and common epigenetic changes between groups revealed that differentially accessible regions (DARs) were found to be increased in ELDR-C1 and -C3 cell lines compared with either EV1 or NT control cells (supplemental Figure 5G; supplemental Table 4) and were mostly located in intergenic regions and introns and not at promoters or enhancer sites (supplemental Figure 5H).

Heat maps and volcano plots revealed that both ELDR-C1 and -C3 lines had more regions that were less accessible or “closed” than more accessible or “open” compared with EV controls (supplemental Figure 6A-B). To find specific genomic loci that were specifically altered in ELDR-overexpressing lines, UpSet plots were generated to identify intersecting DARs (Figure 7A). A high number of DARs were observed when EV1 THP-1 control cell line was compared with NT THP-1 cells (Figure 7A), indicating an effect of the establishment of the ELDR-overexpressing and control cell lines, likely due to the transfection with the expression vector and the subsequent selection process. To exclude effects due to the process of establishing cell lines, we chose those DARs that appeared in the comparison between ELDR-C1 and -C3 cell lines each vs EV1 control (Figure 7A, arrow).

Chromatin accessibility in ELDR-overexpressing AML cell lines. (A) ATAC-seq was performed in ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs EV control cell line (EV1) and NT cells. UpSet plot revealing the intersection of annotated regions in DARs from the ATAC-seq analysis indicated comparisons colored by genomic localization. The overlap of ELDR-overexpressing lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs control EV1 cells each contains 94 DARs (black arrow). Overlap of ELDR-overexpressing lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs control EV1 cells and vs NT cells each contain 44 DARs (asterisk). (B) Volcano plot of the 94 DARs identified in the UpSet plot under panel (A) indicating the DARs that are lost (closed) or gained (opened). The 39 α-satellite–containing regions are more closed in ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs control EV1 cells. (C) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap between proteins identified by ChIRP-MS to interact with ELDR and proteins that bind the centromere specific histone variant CENP-A.35,36 (D) Alignment of RNA-seq (from supplemental Figure 6C), ATAC-seq, and indicated ChIP-seq data at the α-satellite repeat containing centromere and neighboring regions of chromosome 5 to illustrate the localization of DARs and the binding of MLL-AF9, MLL, AF9, RUNX, and transcribed genes using the integrated genome viewer. Data for MLL-AF9 target genes by the MLL-AF9-Flag fusion protein were from GSE103947, data for MLL and AF9 were from GSE79899,37 and the data set for RUNX1 was from GSE217171. (E) Representative IMARIS-based 3D reconstruction of nuclei stained for centromeres for MLL-AF9 and smFISH for ELDR. (F) Magnification of the areas labeled “i-v” in panel (E) revealing colocalizations of ELDR and MLL-AF9 within 240 nm (blue and purple spots), centromere and MLL-AF9 within 500 nm (green and pink spots), and centromere and ELDR within 500 nm (green and pale blue spots). (G) Quantification of the colocalization of ELDR with MLL-AF9 per cell. n = 78 cells per condition. (H) Percentage of MLL-AF9 spots colocalized with ELDR or not over all MLL-AF9 spots. (I) Quantification of spots indicating colocalization of ELDR and centromere per cell. mEldr (murine Eldr) and IgG control (78 cells), ELDR and IgG control (78 cells), ELDR and centromere (74 cells). (J) Quantification of the percentage of cells among all analyzed cells with localization of ELDR/MLL-AF9 complexes in the vicinity of the centromere (radius 0.5 μm). (K) Quantification of ELDR-MLL-AF9 complexes in the vicinity of a centromere per cell with controls. n = 78 cells per condition. (L) Expression levels of the RNA of the HOR D5Z2 at the centromere of chromosome 5 in ELDR-overexpressing lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs EV1 assessed by RT-qPCR. Data are presented as mean +SD from 3 independent experiments. ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using parametric unpaired t test (panel L).

Chromatin accessibility in ELDR-overexpressing AML cell lines. (A) ATAC-seq was performed in ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs EV control cell line (EV1) and NT cells. UpSet plot revealing the intersection of annotated regions in DARs from the ATAC-seq analysis indicated comparisons colored by genomic localization. The overlap of ELDR-overexpressing lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs control EV1 cells each contains 94 DARs (black arrow). Overlap of ELDR-overexpressing lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs control EV1 cells and vs NT cells each contain 44 DARs (asterisk). (B) Volcano plot of the 94 DARs identified in the UpSet plot under panel (A) indicating the DARs that are lost (closed) or gained (opened). The 39 α-satellite–containing regions are more closed in ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs control EV1 cells. (C) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap between proteins identified by ChIRP-MS to interact with ELDR and proteins that bind the centromere specific histone variant CENP-A.35,36 (D) Alignment of RNA-seq (from supplemental Figure 6C), ATAC-seq, and indicated ChIP-seq data at the α-satellite repeat containing centromere and neighboring regions of chromosome 5 to illustrate the localization of DARs and the binding of MLL-AF9, MLL, AF9, RUNX, and transcribed genes using the integrated genome viewer. Data for MLL-AF9 target genes by the MLL-AF9-Flag fusion protein were from GSE103947, data for MLL and AF9 were from GSE79899,37 and the data set for RUNX1 was from GSE217171. (E) Representative IMARIS-based 3D reconstruction of nuclei stained for centromeres for MLL-AF9 and smFISH for ELDR. (F) Magnification of the areas labeled “i-v” in panel (E) revealing colocalizations of ELDR and MLL-AF9 within 240 nm (blue and purple spots), centromere and MLL-AF9 within 500 nm (green and pink spots), and centromere and ELDR within 500 nm (green and pale blue spots). (G) Quantification of the colocalization of ELDR with MLL-AF9 per cell. n = 78 cells per condition. (H) Percentage of MLL-AF9 spots colocalized with ELDR or not over all MLL-AF9 spots. (I) Quantification of spots indicating colocalization of ELDR and centromere per cell. mEldr (murine Eldr) and IgG control (78 cells), ELDR and IgG control (78 cells), ELDR and centromere (74 cells). (J) Quantification of the percentage of cells among all analyzed cells with localization of ELDR/MLL-AF9 complexes in the vicinity of the centromere (radius 0.5 μm). (K) Quantification of ELDR-MLL-AF9 complexes in the vicinity of a centromere per cell with controls. n = 78 cells per condition. (L) Expression levels of the RNA of the HOR D5Z2 at the centromere of chromosome 5 in ELDR-overexpressing lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 vs EV1 assessed by RT-qPCR. Data are presented as mean +SD from 3 independent experiments. ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using parametric unpaired t test (panel L).

Among the common 94 DARs identified by comparing ELDR-C1 and -C3 lines with EV1 controls, only 1 promoter site and 3 sites in the exons were found. Accordingly, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of ELDR-overexpressing lines (ELDR-C1 and -C3) and EV controls revealed differential expression of only a few genes (supplemental Figure 6C-D). None of these genes were localized in the vicinity of DARs found in the ATAC-seq experiment. This suggests that the transcriptional changes observed in the RNA-seq experiments are likely indirect and not directly caused by ELDR.

Most DARs identified by comparing ELDR-C1 and -C3 lines with EV1 were intronic and intergenic sites (22 and 68, respectively). Of these intergenic sites with reduced accessibility, 39 were in the α-satellite repeats of centromere regions notably in chromosomes 1, 5, and 19 (Figure 7B; supplemental Table 5). Among the 44 DARs common between the comparisons of ELDR-C1 and -C3 lines with EV1 and NT controls (Figure 7A, asterisk), 23 were intronic sites and 18 were intergenic sites (supplemental Table 5), suggesting that high level of ELDR expression renders specific chromatin regions, outside of promoter and enhancer sites, less accessible.

MLL-AF9 and ELDR are in close proximity to each other at centromeres

Several proteins identified by ChIRP-MS to bind to ELDR such as TOP1, BAZ1B, SUPT16H, and NPM1 (Figure 5E-H; supplemental Figure 5C) were also reported to interact with the centromere histone variant CENP-A38 (Figure 7C). Therefore published ChIP-seq data sets generated with B-ALL cells expressing Flag-tagged MLL-AF9 proteins (GSE103947) were aligned with the ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data generated with ELDR-C1, ELDR-C3, and EV control cell lines. In addition, 2 individual ChIP-seq data sets for MLL and AF9 (GSE79899)37 and a ChIP-seq data set for RUNX1 (GSE21717139) were aligned as a control. These alignments revealed that the MLL-AF9 fusion protein can occupy α-satellite repeats in the centromeres of chromosomes 1, 5, and 19, exactly where the DARs identified in ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cells are located (Figure 7D; supplemental Figure 7A-B). Similarly, ChIP-seq data indicated that MLL and AF9 alone also occupy α-satellite repeats in the centromeres of chromosomes 1, 5, and 19, but not RUNX1, which was used as a control (Figure 7D; supplemental Figure 7A-B). In this data set, MLL-AF9 demonstrates occupation of its known target genes outside of centromeres (supplemental Figure 7C).

Next, an antibody was used to detect MLL-AF9 in combination with smFISH for ELDR and antibodies for centromere staining, and a potential proximity or colocalization in the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell line ELDR-C1 using the IMARIS image software was measured (Figure 7E-F). The 3D reconstructions from smFISH and immunofluorescence images followed by quantification revealed >40 colocalizations of ELDR and MLL-AF9 spots per cell and indicated that ∼60% of MLL-AF9 proteins are colocalized with ELDR within 240 nm (Figure 7G-H). In addition, the 3D reconstruction confirmed that ELDR is in close proximity of 2 to 3 centromeres per cell and that close to 50% of cells analyzed demonstrate ELDR/MLL-AF9 spots colocalized or in close proximity to the centromere sequences with ∼2 ELDR/MLL-AF9/centromere complexes per cell (Figure 7I-K). These findings suggested a link between ELDR, MLL-AF9, and α-satellite repeats at the centromere in THP-1 AML cells.

Transcription at α-satellite repeats is downregulated in ELDR-overexpressing cells

Human centromeres consist of repetitive α-satellite DNA, organized in megabase-long arrays called higher order repeats (HORs).40 Transcription at centromeres is necessary for proper chromosome segregation, and it is known that α-satellite DNA is transcribed into repetitive non-coding RNA which are divided in 5 suprachromosomal families. The 3 main families (SF1-3), which represent most α-satellite HORs, are found at the centromere core (ie, at the kinetochore-forming region).41 The ATAC-seq results suggested that ELDR overexpression affects SF1 arrays, predominantly on chromosomes 1, 5, and 19 (supplemental Table 5). Human chromosome 5 contains 2 HORs, called D5Z1 and D5Z2, and their expression can be tested by specific primer sets.42 Although RNA expression for the D5Z1 HOR was undetectable, the D5Z2 specific RNA was downregulated in ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 lines ELDR-C1 and -C3 compared with the EV1 control cells (Figure 7L).

Discussion

In this work, the SNAG domain transcription factor GFI1 is revealed to repress transcription of the lncRNA ELDR in human AML cell lines, and this repression is sensitive to LSD1 inhibitors. AML cell lines overexpressing the lncRNA ELDR were unable to grow when transplanted into NSG mice, and the survival of animals that received ELDR-overexpressing AML cells was significantly prolonged. A trans effect of the ectopic expression of ELDR was not detected. The inactivation of the ectopic ELDR sequences restored a normal THP-1 phenotype regarding cell cycle progression, CD11b expression, and tumorigenicity in xenografts, which supports a direct antileukemic effect of ELDR. Expression levels of ELDR were low in a series of AML cell lines regardless of MLL-r status, but also on the bone marrow, blood, and primary human AML and other cancer cells and were inversely correlated to high expression of GFI1. The finding of this study that forced overexpression of GFI1 further reduced endogenous ELDR expression and that a knockout of GFI1 or treatment with LSD1 inhibitor that disrupts the GFI1/LSD1 complex induces ELDR expression suggested that GFI1 directly restricts the expression of ELDR.

Because ELDR could be confirmed to affect DNA replication fork progression, the increased EdU incorporation, which reflects the total incorporation of nucleotides in genomic DNA during the labeling period, observed in ELDR-overexpressing cells was intriguing. It is possible that ELDR-overexpressing cells increase the number of active origins via unknown mechanisms, thereby leading to increased total nucleotide incorporation even though individual replication forks are in general less processive. Furthermore, although ELDR associates with DNA repair proteins such as PARP1, the absence of elevated γH2AX or recruitment of RPA70 to chromatin in S phase cells overexpressing ELDR makes a defect in DNA repair or an increased DNA damage unlikely.

Cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle can either progress through the S phase and replicate DNA or undergo differentiation. Because progression through the S-phase affected ELDR-overexpressing cells, it is not unlikely that these cells have a propensity to differentiate. Several observations support a function of ELDR facilitating differentiation of AML cells: (1) ELDR-expressing AML cells resemble differentiated myeloid cells when treated with ATRA, (2) they upregulate differentiation markers such as CD11b, and (3) they have a higher frequency of cells in the G1 phase and a lower frequency of cells in the S phase compared with controls. Moreover, the growth of ELDR-overexpressing cells can be further reduced by a combination of LSD1 inhibitor and ATRA, 2 reagents known to induce differentiation. Hyperproliferative cancer cells face increased replication stress, which can result in accumulation of DNA damage, leading to cell cycle arrest and, in the case of myeloid leukemia, to differentiation.43 Furthermore, NF-κB–mediated p21 activation controls DNA damage-induced myeloid differentiation.44 Hence, it is conceivable that a link between DNA damage–induced growth arrest and differentiation for myeloid leukemia as reported here in ELDR-overexpressing cells exists.

ELDR-overexpressing cells demonstrate altered chromatin accessibility at specific regions, which were mostly outside promoter or enhancer sites, consistent with RNA-seq experiments in this study indicating that ELDR does not act as a regulator of transcription. Centromeres consist of a distinct class of nucleosomes containing the centromere-specific histone H3 variant, CENP-A (centromere protein A).38 MLL-AF9 and MLL-AF4 oncofusion proteins, which are characteristic for the THP-1 and Mono-Mac-1 cell lines used in this study, have also been found to localize to centromere sequences.45,46 In addition, MLL-AF9 influences H3K4 methylation, crucial for centromeric transcription and function. Because ELDR alters chromatin accessibility and α-satellite RNA expression and binds to NPM1, a nucleolar protein that interacts with CENP-A for centromere assembly and clustering of centromeres around the nucleolus,45-48 it is conceivable that ELDR is localized at centromeres. The 3D imaging data of this study revealed not only that ELDR can be located at centromeres but also that it can be found together with MLL-AF9. It is thus likely that ELDR, when expressed at high levels, associates with MLL-AF9 at centromeres of leukemic cells and impedes cell division by interfering with centromere functions.

These findings also offer an explanation why an effect of forced ELDR specifically in AML cells with MLL rearrangements and not in other AML cells such as those with t(8:21) translocations was observed. It is possible that in MLL-r AML cells ELDR interferes with the access of MLL-AF9 to centromere sequences, at least to those in chromosomes 1, 5, and 19 and blocks the centromere-specific activity of this fusion protein, which is not the case in other AML subtypes, such as Kasumi-1 cells. The downregulation of α-satellite–specific transcripts in ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cells supports this model further because it is likely a consequence of reduced chromatin opening in this region. This scenario is also in accordance with the fact that MLL1 and SETD1A have been reported to be essential for centromeric transcription and the maintenance of centromere identity.46

A possible therapeutic approach using ELDR could be the encapsulation of the RNA into lipid nanoparticles conjugated with an antibody against markers expressed on myeloid leukemia cells to ensure cell type-specific targeting. In addition, chemotherapeutic drugs currently used to treat AML could be added to the ELDR-loaded Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs). Such a new formulation would have the benefit to transport these drugs along with ELDR specifically to target cells avoiding the side effects of a systemic application of chemotherapeutic drugs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mathieu Lapointe and Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montreal (IRCM) animal facility personnel for excellent technical assistance, Manon Laprise and Hugues Beauchemin for help with xenograft experiment and visualization of leukemia dissemination in mice, and Dominic Filion for assistance with microscopy. The authors thank Martin Sauvageau for reading the manuscript and providing many helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through a foundation grant (FDN 148372) and a project grant (PJT 186050) and by the IRCM Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: K.A. contributed in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, and writing; J.R. contributed in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, and methodology; E.-M.P. contributed in formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, and methodology; L.L. contributed in methodology; V.C. and G.R. contributed in analysis, validation, and methodology; M.V. and E.S.-H. contributed in investigation, visualization, and methodology; H.W. contributed in conceptualization and methodology; B.T.W. contributed in validation, methodology, and writing; and T.M. contributed in conceptualization, resources, data curation, supervision, funding acquisition, investigation, visualization, writing of the original draft, project administration, and revisions and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tarik Möröy, Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal, 110 Ave des Pins Ouest, Montreal, QC H2W 1R7, Canada; email: tarik.moroy@ircm.qc.ca.

References

Author notes

The following data from this manuscript are publicly available in a repository: RNA sequencing and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing data at the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession numbers GSE273380 and GSE273382); and the experimental data from Chromatin Isolation by RNA Purification-Mass Spectrometry (ChIRP-MS) at Massive/Proteome Xchange: https://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/dataset.jsp? (accession number MSV000095509).

All other data from this manuscript or the supplemental information are available as follows: primer sequences are provided in supplemental Table 6; and vector sequences and all microscopic image raw files are available on request from the corresponding author, Tarik Möröy (tarik.moroy@ircm.qc.ca).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![ELDR overexpression induces differentiation of THP-1 cells and renders them sensitive to LSD1i/ATRA. (A) Microscopic images of cells from the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 after treatment with ATRA or vehicle (EtOH) compared with an EV1ctrl after May Grünwald Giemsa staining. The arrows indicate more differentiated cells. (B) Quantification of 3 independent replicates of experiment as described in panel (A) after May Grünwald Giemsa staining. (C-D) CD11b levels (MFI [mean fluorescence intensity] by flow cytometry) measured after 3 days of incubation of ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 and the EV1 line with increasing concentrations of ATRA (C) or 10 nM ATRA and increasing concentrations of LSD1i (D). (E) CD11b EC50 values for MFI of the experiments in panels (C-D). (F-H) Growth curves of the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 in the presence of LSD1i, ATRA, or both. n = 3 biological replicates. The growth curve for EV1 is also revealed as a reference. (I-J) Growth of ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 THP-1 lines compared with the EV1 control in the presence of the indicated inhibitors midostaurin (FLT3 inhibitor) and pinometostat (DOT1L inhibitor). n = 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean + SD (panel B); ± SD (panels C-D, F-J). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (panel B); 2-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (panels C-D); parametric unpaired t test (panels F-J). EtOH, ethanol; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; EV1, empty vector 1; LSD1i, lysine specific demethylase 1 inhibitor; FLT3, Fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 3; DOT1L, DOT1 like histone lysine methyltransferase; ns, not significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/23/10.1182_bloodadvances.2024015427/1/m_blooda_adv-2024-015427-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1767901536&Signature=Fzi6lLpCQ~-VZ7C2qiJlNgNJ2T3Rabc3LSWB3GcmtR0ot9msWz2r4dQfOAxcC4w8oMI9pnZmo9xSD7gEj1paESu1EK9nGnhadHWL4U9ognGuV31sMWDKQqy9ghzq75L38SshQD4-Dy7012UvQIQ9Z2o4um7FyNFFFrNQdYWdbnt6GTMILmccXa4R2IuIEkDfM3MLXGsiCtuRnjz4CAPNsSKTR2dJd5lgB5veFbp7RXBWNMADwatfn2BI0vhUc6ZJ~DkCMfotnVOgf012Mkf2iU-~91BD9IlMfQV7jg3ZaLwDNRVwDlIm21zRxL6oRU9VAcj55sx6336CdmZprLkyoA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![ELDR overexpression induces differentiation of THP-1 cells and renders them sensitive to LSD1i/ATRA. (A) Microscopic images of cells from the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 after treatment with ATRA or vehicle (EtOH) compared with an EV1ctrl after May Grünwald Giemsa staining. The arrows indicate more differentiated cells. (B) Quantification of 3 independent replicates of experiment as described in panel (A) after May Grünwald Giemsa staining. (C-D) CD11b levels (MFI [mean fluorescence intensity] by flow cytometry) measured after 3 days of incubation of ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 and the EV1 line with increasing concentrations of ATRA (C) or 10 nM ATRA and increasing concentrations of LSD1i (D). (E) CD11b EC50 values for MFI of the experiments in panels (C-D). (F-H) Growth curves of the ELDR-overexpressing THP-1 cell lines ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 in the presence of LSD1i, ATRA, or both. n = 3 biological replicates. The growth curve for EV1 is also revealed as a reference. (I-J) Growth of ELDR-C1 and ELDR-C3 THP-1 lines compared with the EV1 control in the presence of the indicated inhibitors midostaurin (FLT3 inhibitor) and pinometostat (DOT1L inhibitor). n = 3 biological replicates. Data are presented as mean + SD (panel B); ± SD (panels C-D, F-J). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. P values were calculated using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (panel B); 2-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test (panels C-D); parametric unpaired t test (panels F-J). EtOH, ethanol; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; EV1, empty vector 1; LSD1i, lysine specific demethylase 1 inhibitor; FLT3, Fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 3; DOT1L, DOT1 like histone lysine methyltransferase; ns, not significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/23/10.1182_bloodadvances.2024015427/1/m_blooda_adv-2024-015427-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1767901537&Signature=gORmkQdtcYnRKoFG-DHEVT8CN8ZGVbAWA4wCZK3aC67t0lSzVIociDbGgeAEqZJ25T14KdzRu0Y8YFAznGWVdU8554n10139upjSdOo-8BQhAn4kQVnQMrV-djx8HrETwhYIpRBhP8AXLMxK8Xq2ezGBIcPlVa~d~x6xWOr-Wh8329n7in7Luy3A3QszIUrlEy~esfYim-FC1N8yWCoHWR~XSovFGCzYBhZ5jI-y1yC32XlmGOwuNyxeQrrCge8PMRwJGfzWjSsOgqFSrumhr0LMslQBxn0JjUENr8rH9UBRrM~D5LnnHYLqiiGaLEg96dvwLlYGSjfQRpOe4GijmQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)